Paul Finch's Blog, page 13

February 11, 2018

Out and about in 2018: the big diary dates

Okay, we’re well into 2018 now, and that semi-surreal period around Christmas and New Year feels as if it’s a long, long way behind us. Time now to get on with this year’s events. So, today I intend to talk about my calendar for the next few months, and the various public appearances I’ll be making, and the circumstances surrounding them. Sorry, if that sounds a little self-indulgent, but quite honestly, it’s in response to questions I get asked a lot – about when I’ll be out and about, when I’ll be able to sign books for people, and the like.

Okay, we’re well into 2018 now, and that semi-surreal period around Christmas and New Year feels as if it’s a long, long way behind us. Time now to get on with this year’s events. So, today I intend to talk about my calendar for the next few months, and the various public appearances I’ll be making, and the circumstances surrounding them. Sorry, if that sounds a little self-indulgent, but quite honestly, it’s in response to questions I get asked a lot – about when I’ll be out and about, when I’ll be able to sign books for people, and the like.Also today, I’ll be reviewing and discussing a very different kind of crime thriller, Andrew Taylor’s compelling historical murder mystery, THE ASHES OF LONDON.

As usual, you’ll find that review towards the lower end of today’s blogpost. Before we get there, as I threatened, here are some dates and venues that might be of interest if you ever feel like saying ‘hello’ face-to-face.

Be aware that this is probably an incomplete list at this stage. There may well be one or two cancellations, and there will certainly be one or two additions. In that regard, the only advice I can give is stay tuned, watch this space, etc etc.

On March 24, I’m honoured to be a guest at The Quad in Derby, where the Horror Writers Association will present PARTNERS IN CRIME .

Through exclusive interviews, informative panel discussions and expert talks, attendees will be able to learn more about crime fiction’s edgier side, examining how thrillers have become darker, how serial killer fiction now tends to form a natural bridge between the two genres, and asking the question is there a place for the supernatural in crime fiction?, and if so, how can authors can benefit from this ever more visible overlap?

Through exclusive interviews, informative panel discussions and expert talks, attendees will be able to learn more about crime fiction’s edgier side, examining how thrillers have become darker, how serial killer fiction now tends to form a natural bridge between the two genres, and asking the question is there a place for the supernatural in crime fiction?, and if so, how can authors can benefit from this ever more visible overlap?There will also be the usual opportunities to purchase books and get them signed, and to socialise with authors and publishers.

At this stage, I’ll be involved in the following panel chats: I, Monster: Has the Serial Killer replaced the monster in modern dark literature? And: Taboo! How dark is too dark?

But of course, Partners in Crime isn’t just about me. Other guests include some fairly hefty names in the industry. Check these out: Stuart MacBride, Fiona Cummins, AK Benedict, Steph Broadribb, Barry Forshaw, SJ Holliday, Joe Jakeman, David Mark and Roz Watkins.

May 17-20, I’ll be at

CRIMEFEST

in Bristol. For the first time in what seems like ages, I’m neither guesting on a panel nor chairing one during this festival, so I guess that means I’ll have more bar-time if anyone wants to chat.

May 17-20, I’ll be at

CRIMEFEST

in Bristol. For the first time in what seems like ages, I’m neither guesting on a panel nor chairing one during this festival, so I guess that means I’ll have more bar-time if anyone wants to chat.For anyone who’s not been to CrimeFest (where the pen is bloodier than the sword), it’s a great event if you’re interested in crime fiction, either as a reader or a prospective writer – and it’s for occasional fans too, not just the die-hard fanatics. It’s certainly now become one of the biggest crime fiction events in Europe, and it’s no surprise that every year it draws top crime novelists, editors, publishers and reviewers from around the world, giving all delegates the opportunity to celebrate the genre in a friendly, informal and inclusive atmosphere.

The two guests-of-honour this year will likely have copies of their books on almost every crime enthusiast’s shelves: Lee Child and Jeffery Deaver.

On June 14, I’ll be at the CROSSING THE TEES Book Festival. This is a large-scale literary event organised by the library services of Stockton, Middlesbrough, Hartlepool, Redcar & Cleveland, and Darlington. It’s early days on this one so far, so I’ve not got any detail about my own role in this grand event yet, or a comprehensive list of the other guests, but can guarantee that it will be worth attending at some point if you enjoy books. It runs from June 9-24, and includes all kinds of author events, workshops, lectures, readings, competitions and the like.

July 19-22, I’ll be making my annual trip to Harrogate for the THEAKSTON OLD PECULIAR CRIME WRITING FESTIVAL .

In short, this is one of the biggest of them all, and is a massive celebration of the genre, which has deservedly won huge international acclaim. The event is also known for its no barriers approach, as fans, writers – both newcomers and established superstars – agents, publishers and editors mingle in the hotel bar, bookshop and the huge pavilions set up in the grounds of the historic Swan Hotel in the leafy heart of Harrogate (pictured above).

In short, this is one of the biggest of them all, and is a massive celebration of the genre, which has deservedly won huge international acclaim. The event is also known for its no barriers approach, as fans, writers – both newcomers and established superstars – agents, publishers and editors mingle in the hotel bar, bookshop and the huge pavilions set up in the grounds of the historic Swan Hotel in the leafy heart of Harrogate (pictured above). Again, there’ll be panels, discussions, author interviews, interactive events and all kinds of activities in the bar areas. Perhaps the most attractive feature of the Harrogate event is the accessibility it provides to some of the biggest names in the business. For example, the first headliner announced for this year is powerhouse US author, Don Winslow (right).

Again, there’ll be panels, discussions, author interviews, interactive events and all kinds of activities in the bar areas. Perhaps the most attractive feature of the Harrogate event is the accessibility it provides to some of the biggest names in the business. For example, the first headliner announced for this year is powerhouse US author, Don Winslow (right).That alone should be reason for many crime fans to flock there. But the main thing is, you can doorstop these guys and girls and simply chat to them. If they weren’t prepared for that, they wouldn’t be there. And of course, this can be even more useful if you’re a new writer looking for an agent or a publisher – because they are there to, and, whereas in real life, it’s often difficult to get any kind of meeting with these folks, at Harrogate all you need to do is say hello.

And say it to me as well, if you wish – because as I say, I’ll be mingling there with everyone else.

Two crime fiction events coming up in the latter half of the year, which I’m hopeful of attending – but not absolutely certain of this stage – are BLOODY SCOTLAND, the annual Caledonian Crime-Writing Festival, which is held in Stirling from September 21-23, and MORECAMBE & VICE, at the incredibly atmospheric venue of the Morecambe Winter Gardens on September 29-30.

Last on the diary (so far), but not by any means least, we have a slight change of pace, with FANTASYCON at Chester, October 19-21, when I’ll be wearing my horror hat.

For those not aware, Fantasycon is another of the great annual literary events, attended by writers both great and small, agents, editors, publishers and the like, though this one concentrates on fantasy fiction (which also includes horror and sci-fi). Given that this is late October, it’s a little early in the day for me to provide any details – either concerning guests of honour, specific events, book launches and the like, or what I myself will be doing there (most likely I’ll just be an everyday delegate, happy to hold up the bar and chat). Again, for more info, watch this space.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE ASHES OF LONDON

THE ASHES OF LONDON

by Andrew Taylor (2017)

It is 1666 and London is burning. Apparently, it ignited by accident, but it’s burning nonetheless … from the Tower to the Temple Bar, the wailing populace struggling to escape as their homes and workshops succumb to the flames.

But even without the fire, these are turbulent times in England. After an exhausting civil war and then years of Cromwellian rule, the Stuarts are back on the throne in the form of the affable Charles II, but enemies of the crown are never far away. Puritan forces linger in the shadows, some more dangerous than others, such as the Fifth Monarchists, a fanatical clique who were not just involved in the execution of Charles I – ‘the Man of Blood’, as they called him – but who are also keen to see his son dead, thus clearing the way for the accession of ‘King Jesus’ and ushering in a reign of Heaven on Earth.

Against this difficult and dangerous background, what is one more death? But even in the midst of the fire, attention is captured by the discovery in the ruins of St Paul’s of a man who has been ritually assassinated, his thumbs tied together behind his back before he was stabbed.

The authorities have a bit too much on their plate to be overly interested in this, but it isn’t simply ignored, the investigation put into the hands of one James Marwood, a young man who on the outside doesn’t seem like much of a sleuth. Ostensibly, he’s an ordinary chap who is simply trying to make his way in the world, with zero interest in the affairs of state, but his is a more complicated path than most. The son of a republican activist who was ruined financially by the restoration of the monarchy, not to mention in terms of his reputation and health, James Marwood now works as a clerk for Joseph Williamson, chief propagandist for the Royal Court, in the pamphleteer office at Scotland Yard, where he is trusted but treated brusquely.

The authorities are well aware of James’s past, of course, and perhaps have employed him on the basis that it’s advisable to keep your friends close and your enemies closer still. But he now becomes even more useful for them. Detecting the hand of republican extremism in the recent murder, they assign James to the case because it’s deemed possible that his family may still have contacts in that secretive world.

At the same time, in what is initially a parallel storyline, we meet Catherine Lovett, or ‘Cat’ for short, the daughter to and heiress of Tom Lovett, a one-time Cromwellian soldier and ‘regicide’ – in other words he was directly involved in the execution of Charles I, and therefore can never be pardoned – who is currently in hiding. Almost oblivious to this background chicanery, Cat, who commences the book as an adventurous but on the whole fairly innocent girl, wants only to design buildings and study architecture, though alas, even these simple dreams are far from being realised. In the absence of her father, she is the unhappy ward of her wealthy aunt and uncle, Olivia and Henry Alderley, the latter of whom wants only to marry her off and be done with her. As if that isn’t distressing enough, Cat’s odious cousin Edward is increasingly interested in her, and when he finally rapes her, and she retaliates by half-blinding him, she flees into what remains of the smouldering city and seeks out a new (inevitably much harsher) life for herself.

We know these personal journeys are going to entwine at some point, but The Ashes of London is such a plot-driven novel that to give any more detail at this stage would be the ultimate spoiler. Suffice to say that all kinds of skulduggery follows, James and Cat pursuing their own meandering and perilous paths through a world of intrigue as they are drawn steadily together.

In addition, endless fascinating and outrageous characters take the stage. Cat comes under the paternalistic spell of a kindly but ailing draughtsman, Hakesby, who, alongside the legendary Christopher Wren (who also makes an appearance), is charged with re-designing the burned-out cathedral. James, meanwhile, is introduced to the devious William Chiffinch, another real-life personality and one of Charles II’s most accomplished fixers. When the king himself arrives, it is in dramatic and amusing fashion, which is the way it should be, because though his is little more than a glorified guest-appearance, Charles II, as the embodiment of the Stuart royal line, remains essential to the narrative.

While all this is going on, of course, the murder plot thickens, the bodies piling up, Marwood’s suspicions spreading in all directions, particularly where high-end political machinations may be found (yes, this is a conspiracy thriller as much as a murder mystery). And all the way through there is a growing sense of jeopardy. Neither Cat nor James have such status that they command power, and even though James represents power, it is not always around to assist him when he needs it. So, it isn’t just the villains of the piece – an increasingly dangerous and deranged threat, we sense – who provide the menace. Bad things can befall almost anyone, for near enough any reason, if they poke their noses deep enough into the ashes of London …

The Great Fire of London is a disaster that is branded into the psyche of most Britons, even those who are not overly familiar with the historical period. It was a monumental event for all kinds of reasons, and a milestone in the emergence of the Modern Age, not least because it cleared away what remained of the old medieval city and allowed visionaries like Christopher Wren to build something vastly more advanced. But it’s important to remember that just because the city that burned was centuries old at the time, it was not some miniature wattle-and-thatch market-town, some tangle of narrow streets and muddy courts on the banks of the Thames. It was already colossal in size, a megalopolis that was home to 80,000 people, 70,000 of whom were rendered homeless by the 1666 disaster.

Little wonder this event was viewed at the time as a national catastrophe, especially because it came on the coat-tails of the Black Death, and so was viewed by religious extremists as part of a double-punishment imposed by God for the lax morality of the Restoration era.

Britain in the mid/late 17th century was certainly a cradle of fundamentalism, a land divided between various religious groups, (most of them Protestant, while Catholics were regarded as traitors who deserved to be lynched simply for being Catholic!). Oliver Cromwell’s dictatorial rule was over and the Royalists were back in power, but the Puritans had not gone away. Though most had officially been forgiven for their roles in the Civil War, countless gentleman still held positions of authority even though their loyalty was suspect, while remnants of the brutal Roundhead army lurked among the general populace, in some cases functioning like miniature crime syndicates. In a time and place when it was an offence just to hold an opinion, the king’s spies were everywhere. London was a city of informers, and no-one trusted anyone else.

And then the fire came, a conflagration quite literally – or so it seemed – from Hell.

And it is this epic sprawl of religious and political intrigue, not to mention the incendiary atmosphere of a truly pivotal moment in British history, that Andrew Taylor captures so perfectly in The Ashes of London . But don’t for one minute assume that this means it’s a history lesson. From the very beginning, this is a fast-moving mystery, with living and breathing characters striking sparks off each other as they wend their labyrinthine ways through a capital city (what’s left of it!) filled with danger and deception.

And yet the richness of historical detail is all here, blended seamlessly into plot and dialogue. For example, we come to understand the destructive power of the fire because when it’s over, we trudge the desert of cinders for ourselves. We see what a Machiavellian hive the Palace of Whitehall was because we view it, if not simply through the eyes of hero, James Marwood, who only ever receives information on a ‘need to know’ basis, but via the manners and methods of crafty functionaries like Williamson and Chiffinch. We understand what a focal point of English religious life the original Cathedral of St. Paul’s was because we feel the horror of the awe-stricken crowd as it goes up in flames.

This novel is an out-and-out feast for historical fiction fans, awakening that brief window of time more effectively than any number of textbooks I could name. But for those who are simply here for the thrill of an intense, clue-driven investigation, it won’t disappoint on that level either, telling us a fascinating detective story and setting it against a richly-coloured and yet easily accessible tableau of the past.

As alluded to earlier, it would be erroneous of me to give too much away about the plot as that would spoil the reading experience. It’s complex for sure, but deeply engrossing – you literally never know where the next twist is going to come from. And it helps, of course, that the lead characters are so engaging.

James and Cat, are far from being stock historical heroes, both completely aware of their standing in this unforgiving world, and yet each with their own quirks. The former commences the narrative in a lowly position, but he’s inquisitive by nature and inordinately perceptive, and he grows rapidly into his role of unofficial but opinionated Scotland Yard investigator. The latter is ripped from pillar to post by forces beyond her control, and suffers lasting damage as a result –a realistic appraisal, perhaps, of what it would actually mean to be ‘bodice-ripper’ heroine – and yet she remains feisty and spirited throughout, and at times maybe a little more than that; by the end of this novel, one wouldn’t want to cross Cat Lovett unnecessarily.

The rest of the cast are equally striking, both the real and fictional mingling believably together, all drawn clearly and, perhaps in the way of true life, none of them especially more likeable than the next as they all ultimately look out for themselves. Most interesting of all, maybe, are James and Cat’s two fathers, men who very vividly represent the moral complexities of their age; both are driven by a sincere devotion to an idealised vision of Jesus, but they are heavily politicised too, and so battered by war and oppression that Christian sentiment rarely manifests itself in their actions. Though perhaps the deepest irony where Tom Lovett and old Marwood are concerned is that, given they are both Bible men, neither seems remotely aware of that most prescient warning of the good book: that the sins of the fathers will be visited on their children.

The Ashes of London is an enthralling and informative read. Elegantly written, deeply atmospheric of its period, and yet rapid-fire in terms of its unfolding action and events. I found it utterly compelling, and have no hesitation in giving it my highest recommendation.

As usual, I’m now going to attempt to cast it. This is just for fun, of course (as if any casting director would take note of my views). I have no idea if The Ashes of London is being lined up for film or TV adaptation, but it really ought to be. Here are the actors I would call:

James Marwood – James NortonCat Lovett – Daisy RidleyHakesby – Geoffrey RushWilliamson – Jim CarterChiffinch – Charles DanceHenry Alderley – Jonathon PryceOlivia Alderley – Maria BelloOld Marwood – Patrick StewartTom Lovett – Bernard Hill Charles II – Julian Sands

Published on February 11, 2018 05:30

January 14, 2018

Seeing 2018 through should be a real blast

Okay, I hope everyone had a great Christmas, and happy New Year to you all. I trust you’re all ready to tackle 2018 with the vim and vigour required. Personally, I’m looking for an explosive year, this year – though, by that, I should state that I mean in book terms.

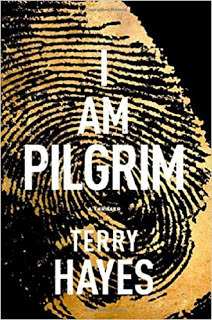

KISS OF DEATH, the seventh DS Heckenburg novel, is published in August this year, and I can promise you now, it’s going to be a big ’un – in every sense of the word. But more about that in a few paras. Also on the subject of explosive thriller fiction, I’m kicking off the New Year by reviewing Terry Hayes’s mesmerising I AM PILGRIM, one of the best international actioners I’ve read in a long, long time.

As usual, you’ll find that review towards the lower end of today’s blog. If that’s all you’re here for, be my guest and skip down there to check it out straight away. But if you’ve got a few minutes to spare first, hang around here, because I’ll also be including a guest-blog I wrote for the FOR WINTER NIGHTS blog back in April last year, in which the question was put to me: What Seven Things Should You Know if You Want to Write Crime Fiction?

But before that …

Though I say it, myself

Even though I say so, myself, KISS OF DEATH is going to be a major event in the Mark Heckenburg story.

Those who’ve followed Heck’s investigations from the beginning (the first one, STALKERS , was published by Avon at HarperCollins way back in February 2013) will be aware that he is now at the end of his thirties, but still, despite some jumping about en route, a detective sergeant with the Serial Crimes Unit, which in its turn is part of Scotland Yard’s National Crime Group.

It wouldn’t be true to say that Heck has had a chequered career, thus far; he’s had some great results, but there’ve been fireworks too. This is partly down to his penchant for going it alone, bending the rules and taking chances. However, if you haven’t read Heck yet, don’t go away from that under the impression that he’s a British version of Dirty Harry. Heck is not some humourless bully or cold-blooded killer. He’s affable and easy-going, but only with

ASHES TO ASHES

(the sixth outing), did we fully become aware just how affected and damaged he is by events in his early past.

It wouldn’t be true to say that Heck has had a chequered career, thus far; he’s had some great results, but there’ve been fireworks too. This is partly down to his penchant for going it alone, bending the rules and taking chances. However, if you haven’t read Heck yet, don’t go away from that under the impression that he’s a British version of Dirty Harry. Heck is not some humourless bully or cold-blooded killer. He’s affable and easy-going, but only with

ASHES TO ASHES

(the sixth outing), did we fully become aware just how affected and damaged he is by events in his early past.Fortunately, he’s always had Gemma Piper to lean on. His ex-girlfriend, who once worked with him as a fellow detective constable at Bethnal Green police station, Gemma has since rocketed to police superstardom and is now the detective superintendent in charge of the Serial Crimes Unit (SCU). They still care a lot for each other, but they don’t often show it, this unspoken chemistry leading them to fight like cat and dog over matters of procedure and morality. Gemma, the ultimate straight-player, is adamant that she will keep Heck on the straight and narrow, while Heck is equally adamant that what Gemma doesn’t get to know about his more ‘out there’ investigations will never actually hurt her.

From an authorial point of view, it’s a relationship between my two lead characters which has worked very well, and which I think has given the ongoing story-arc depth and impetus. Whether two people in real life could exist in this constant state of love/war, especially when they are pursuing some of the most vicious and relentless killers in Britain, is another matter, but hey, this is fiction.

When we get to KISS OF DEATH, though, the whole of the Serial Crimes Unit, not just Heck and Gemma, is under a degree of pressure it has never known before.

It’s 2018 of course, and the austerity that has denuded the police service of so many front-line officers and whittled away at specialist departments has finally come to the National Crime Group. NCG Director, Joe Wullerton, argues daily with the National Police Chief’s Council for the continuation of his department, which does not just track serial killers through SCU, but also contains the Kidnap Squad and the Organised Crime Division. When he puts it to the powers-that-be that to close NCG would be to drastically reduce the police forces of England and Wales’ effectiveness in their fight against the most heinous criminals and their gangs, there is sympathy – but sympathy alone doesn’t pay bills.

Feeling that some pro-action is required on her part, Gemma Piper opts to join forces with the Metropolitan Police’s Cold Case Team who are also facing the axe, and proposes the creation of a temporary task-force dedicated to pursuing the twenty worst British offenders still on the loose, with a remit to get rapid and impressive results.

With the clock ticking, Heck finds himself in partnership with Detective Constable Gail Honeyford, a new recruit to SCU (though he worked with her once before in

HUNTED

, 2015), and someone he likes for her spirit and nous, but whom he also finds bolshy and hot-headed. Their particular target is Ed Creeley, a notorious bank-robber and many-times murderer, who went to ground in 2014 and hasn’t been seen since, though he is still believed to be at large in the UK. Their pursuit of this pitiless hoodlum takes them all over the country, from Humberside to the East End of London, and eventually even to Cornwall, all the way encountering ever more reprehensible villains, ever greater dangers, and increasingly, uncovering clues that something absolutely appalling is happening the United Kingdom – as yet unknown to the British authorities, but which, when they finally discover it, will literally rock SCU (and most other police agencies) to the foundations.

With the clock ticking, Heck finds himself in partnership with Detective Constable Gail Honeyford, a new recruit to SCU (though he worked with her once before in

HUNTED

, 2015), and someone he likes for her spirit and nous, but whom he also finds bolshy and hot-headed. Their particular target is Ed Creeley, a notorious bank-robber and many-times murderer, who went to ground in 2014 and hasn’t been seen since, though he is still believed to be at large in the UK. Their pursuit of this pitiless hoodlum takes them all over the country, from Humberside to the East End of London, and eventually even to Cornwall, all the way encountering ever more reprehensible villains, ever greater dangers, and increasingly, uncovering clues that something absolutely appalling is happening the United Kingdom – as yet unknown to the British authorities, but which, when they finally discover it, will literally rock SCU (and most other police agencies) to the foundations.*

And now for something a little bit different …

As I mentioned earlier, I wrote a guest blog-post for FOR WINTER NIGHTS last April to accompany the publication of ASHES TO ASHES . It seemed to go down very well, so, for those of you who didn’t see it the first time, here is is again:

What seven things should you know if you want to write crime fiction?

Well, it’s an interesting question, and certainly one I haven’t been asked before. Off the top of my head, I can think of seven things it might be useful for you to know. I wouldn’t say that these are the seven most important things, but it probably wouldn’t do you any harm to be forearmed, as they say. So here we go…

1) Guilt goes with the territory

This may seem a curious thing to say, but it reflects reality. By its nature, crime and thriller writing deals with the darker end of the human experience. It won’t just be routine wickedness you are exploring. Whether your lead characters are heroes or villains, they’ll be dicing with danger, skating along the edge of the abyss, doing all kinds of things that law-abiding citizens in normal life never would. Now, if you want your writing to be authentic, you’ve got to go the extra mile to ensure that you get the facts of these matters correct.

That will entail lots of online research into areas you wouldn’t usually go anywhere near, such as the formation and organisation of criminal empires, the methods and modus operandi of serial killers, the anatomies of the world’s most successful bank robberies and/or assassination plots, the use and availability of illegal firearms, the impact upon human bodies of poison, nerve gas, biological weaponry, the formation of police investigation teams and the emergency procedures they follow, the complexities of drugs-trafficking, the risk and probability of terrorist attacks, and the depth and breadth of those security shields that protect western cities against such catastrophic threats.

That will entail lots of online research into areas you wouldn’t usually go anywhere near, such as the formation and organisation of criminal empires, the methods and modus operandi of serial killers, the anatomies of the world’s most successful bank robberies and/or assassination plots, the use and availability of illegal firearms, the impact upon human bodies of poison, nerve gas, biological weaponry, the formation of police investigation teams and the emergency procedures they follow, the complexities of drugs-trafficking, the risk and probability of terrorist attacks, and the depth and breadth of those security shields that protect western cities against such catastrophic threats.All of this is going to make fascinating reading, of course, for a security expert should he/she ever have call to examine your online activity. You will have the excuse that you’re a crime writer and that it’s all part of the game, but that doesn’t mean you won’t feel a tad nervous when you’re indulging in it.

2) You’ll be challenged on facts

Never has the phrase ‘facts matter’ been more relevant than it is to the average crime/thriller writer. One of the most basic problems you have as an author in this field is that you’re straying into a fascinating, complex world which also, rather inconveniently, happens to be real. So, for example, you may be delving into law enforcement with all the procedures, protocols and legalities inherent to that. If you think that’s tough, you may also find yourself concerned with military matters, or security issues involving international law, the intelligence services and/or spec ops deployment. Medical and forensics questions will almost certainly arise; you may need to discuss weapons, explosives and the like. But the real problem is that you’ll likely encounter real-life people in your everyday world who have expertise in these fields, and if you get things wrong, they may call you to account – sometimes in public.

While it’s not incumbent on you to become a guru in these matters, it would certainly help if you did some basic research. Whatever you do, don’t wing it.

(I will add that it won’t matter quite so much with the likes of MI6 and/or the SAS, as they’ll never comment anyway, and almost certainly will be delighted if you spread misinformation about their techniques).

3) You can chat to those who know

Library and internet research may help you factually, but it’s often a dry process and is unlikely to hit you from left-field with cool new ideas. In contrast, speaking to someone who’s actually done unusual things in his/her life can be much more fruitful. And the good thing is, with the exception of those ultra-secret organisations I mention above, most members of the security services are happy to chat about it, though they only tend to do so if approached … so don’t feel awkward about trying to pick their brains.

Police officers or ex-police officers are particularly good in this regard. I have a slight advantage here as an ex-copper, in that they may feel they can trust me more with the really juicy stuff, but I’d be surprised if the majority weren’t willing to have a chat with any writer. There may be certain areas they won’t go if they don’t already know you, but on the whole I think they’ll be willing to talk widely and informatively about their job. Never make the assumption that they’ll think you’re silly. They won’t. Many coppers I know also read crime fiction, while others would like to write – to immortalise their own exploits – but can’t, and so become very protective of writers they form relationships with, as they see that as the next best thing.

4) It is not a solitary profession

4) It is not a solitary professionThe semi-mythical image of the writer slugging on alone in his/her attic, virtually penniless and with no one to call a friend, particularly does NOT apply to the crime/thriller writer. I mean, I can’t comment on the ‘penniless’ bit – that all depends on your personal circs, but you DO have friends.

In all the literary fields, I’ve never known anywhere where the networking between practitioners is quite as vibrant as it is in crime and thrillers. There are literally hundreds of authors writing this material at professional level, both at home and overseas, and they’re all doing exactly the same things you are: hammering away at their keyboards, proof-reading, flipping through websites on the research trail, chatting things over with their agents and editors – and not always to their personal satisfaction. More importantly, thanks to the internet, most of these men and women are now connected. There are all kinds of online crime-writer clubs you can join, places where friendships are made, experiences aired and info shared (including info about which publisher has a new slot available, or which editor is looking for what, which can be very useful indeed). This is a great way to relieve pressure, because it shows that you aren’t the only person struggling with writer’s block, or character development, or just with the sheer physical effort of trying to finish a full-length novel inside a tight deadline. Likewise, there are many crime fiction conventions and festivals you can attend, and crime-writing societies you can join. A burden shared is a burden halved and all that, on top of which a lively social life, especially when it’s crammed with folk who all share the same interest as you, can only improve your quality of life.

5) Readers can take as much as you can give them

Don’t be lulled into thinking that, just because certain sub-genres within the overarching genre of crime writing are cosier than others – a good example being the ‘village green murder mystery’ – you have to handle your readers with kid gloves. In short, it’s quite the opposite.

One of the best examples of village green-style crime fiction in the modern day is the TV series, Midsomer Murders, and look at the body-counts in that, not to mention the various methods of dispatch. We’ve seen people killed with farm-tools, sliced, diced, decapitated, churned up by combine harvesters. One poor chap was beaten to death with cricket balls fired at him out of a batting machine. Crime readers, whatever style they prefer, are generally speaking a ghoulish bunch, who are here to enjoy a dalliance with the darkness. So, don’t hold back. As long as you don’t deal with death in juvenile fashion, you can, on the whole, pile on the grimness and violence. I mean, personally I’m a great believer in less being more, but I don’t think you can pussy-foot around the subject of murder, especially in this modern age when ‘true crime’ is so popular – and there ain’t nothing gorier than ‘true crime’.

So, if you feel you need to lay it on, don’t worry about the sensibilities of your readers. Lay it on.

6) Crime writing is a very broad church (no pun intended)

So many people who don’t read crime/thriller fiction have complete misconceptions about it. They immediately think Agatha Christie and the traditional English whodunnit. That is undeniably there and is very popular.

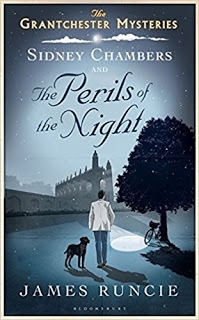

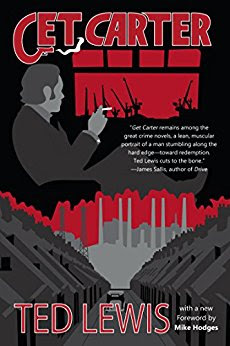

Sidney Chambers, the crime-fighting village vicar of James Runcie’s Grantchester Mysteries, still embodies something of that atmosphere, and his adventures sell widely. But there are other fields too. Our fictional crime-fighters, like crime-fighters in real life, vary across the spectrum – from sticklers for procedure and crusaders of correctness to embittered louts who are never any better than they need to be and subsequently walk tightropes through a world of crime and sleaze. It doesn’t even stop there; often we use hardboiled PIs as our models, the smart-mouthed heroes created by James Crumley, Mickey Spillane and Raymond Chandler, who are no strangers to the seediest worlds imaginable and will play by any rules to win. Sometimes the villains themselves are our central characters. The violent gangland thrillers of Ted Lewis, Malcolm Mackay and Howard Linskey perfectly exemplify this.

Sidney Chambers, the crime-fighting village vicar of James Runcie’s Grantchester Mysteries, still embodies something of that atmosphere, and his adventures sell widely. But there are other fields too. Our fictional crime-fighters, like crime-fighters in real life, vary across the spectrum – from sticklers for procedure and crusaders of correctness to embittered louts who are never any better than they need to be and subsequently walk tightropes through a world of crime and sleaze. It doesn’t even stop there; often we use hardboiled PIs as our models, the smart-mouthed heroes created by James Crumley, Mickey Spillane and Raymond Chandler, who are no strangers to the seediest worlds imaginable and will play by any rules to win. Sometimes the villains themselves are our central characters. The violent gangland thrillers of Ted Lewis, Malcolm Mackay and Howard Linskey perfectly exemplify this.So, there you have it; we range from those quintessential leafy villages in the heart of Middle England to urban hells populated by addicts, prostitutes, contract killers and corrupt politicians. Oh yes, we’ve got it all. Feel free to explore at random.

7) There is no requirement to write on the side of good

7) There is no requirement to write on the side of goodAs I intimated in earlier paragraphs, we are not, as authors, bound by real-world morality.

For my money, one of the best crime thrillers ever written is Jack’s Return Home by Ted Lewis, which was published in 1970 but filmed in 1971, perhaps more famously, as Get Carter. It tells the tale of a mobster from the North of England who makes good in London, but when his brother is murdered back home, gets on a train in a quest for gangland justice. What follows is a brutal, gritty noir filled with anger and darkness, and in the character of Jack Carter, it gives us an amoral and uncompromising hero, a cold-blooded hardman who is only different from the evil hoodlums he finds himself gunning for because his personal code of ethics is marginally more admirable than theirs.

But hey, this again reflects reality. You’ve doubtless heard the phrase ‘it takes a wolf to catch a wolf’. Well, we crime authors mustn’t be ashamed of putting that into practice. Morally ambiguous heroes are often far more interesting than those goodie two-shoes of the old school. In any case, as I say… this is fiction, not real life, so it doesn’t matter anyway. If that’s what you want to do with your book, go for it.

*

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

I AM PILGRIM

I AM PILGRIM by Terry Hayes (2014)

‘Pilgrim’, aka ‘Jude Garrett’, ‘Scott Murdoch’, ‘Pete Campbell’ and in inner spy circles, the ‘Rider of the Blue’, is the enigmatic man who wrote the ultimate manual on forensic analysis. He’s also the offspring of a murder victim and the adopted son and heir to a New England multi-billionaire, while, career-wise, he’s a US intelligence agent, who, even though he’s still very young, is so formidably skilled and experienced, and boasts such an exemplary track record (which included his termination of a powerful and highly dangerous double-agent based in Moscow) that it has earned him the ear of US presidents.

Technically speaking, however, it’s all over for Pilgrim. He’s done, retired, looking forward to a life of bohemian anonymity in the garrets and backstreets of Paris.

But then, over in Manhattan, Detective Ben Bradley, locates the body of a murdered woman whose corpse has been completely depersonalised by the very same CIA-inspired methods that Pilgrim specified in his seminal book, her teeth removed, her fingerprints and facial features erased with acid, and all traces of the killer’s DNA obliterated by judicious use of antiseptic.

Pilgrim – though he isn’t going by that moniker at this early stage – is a lonely and tortured individual, whose empathetic nature was at the root of his seeking an alternative career, and who yearns to forget his past, though now he is inevitably forced back onto the job to assist Bradley’s investigation. After that, it isn’t long before he finds himself embroiled in a connected but much larger and potentially massively more devastating case … which takes us neatly onto I Am Pilgrim ’s other main thread, the personal and political development of an ambitious and determined terrorist, who will also go by a conveniently simple nickname: ‘Saracen’.

After a deprived boyhood in the repressed police state that is Saudi Arabia, which culminates in his having to watch the public decapitation of his father for the unforgivable offence of criticising his nation’s rulers, Saracen finds himself growing up with a fierce hatred for the Saudi royal family, and perhaps inevitably (and far more zealously), for their most committed western ally, the United States of America.

A fully trained doctor by adulthood, but increasingly immersed in the more extremist tenets of Islam, Saracen eventually falls out with what remains of his family (his mother needing to get a job is the final straw!), and he leaves home determined to join the jihadi fight, which he does with a vengeance, soon finding kinship with the Taliban and entering the war in Afghanistan as a soldier of God.

However, Saracen, much like Pilgrim (though this is the only similarity between them), is an obsessive intellectual of his craft, and the winning of minor battles and launching of successful but relatively insignificant terrorist outrages feels like small potatoes. Eager to carry his war into the very heart of his enemy’s domain, and if possible, to destroy it completely, the only solution, as Saracen sees it, is to develop and deploy a bio-weapon of such magnitude that the might of the US will simply collapse beneath its onslaught.

He settles on a new, vaccine-proof and horrendously contagious strain of the smallpox virus (which he unleashes on a batch of human test-subjects in what is surely one of the ghastliest scenes that’s ever been committed to paper).

Back in the States, Pilgrim and his various government informers don’t get wind of this fiendish plot straight away, but when they do, a twisting, turning, continent-hopping duel commences, which ranges from the US to Europe to Asia and the Middle East, taking in a variety of amazing locations en route, including Syria, Switzerland, Bahrain, the bleak, savage mountains of the Hindu Kush, and a hypnotically beautiful Roman ruin on the edge of the glimmering blue Aegean. Ironically, Pilgrim and Saracen don’t meet until near the end of the book, but this doesn’t stop either of them engaging in numerous conflicts on the way, via flashback and subplot and through various proxies, though ultimately we finish up in a shattering, race-against-the-clock, one-on-one climax, which, if I was to say more about it here would be the ultimate spoiler …

The Guardian said of I Am Pilgrim that it’s ‘the only thriller you need to read this year’. Speaking as a gobbler-up of thrillers, I wouldn’t go quite that far, but I do know what they mean. Everything about Terry Hayes’s astonishing debut novel is epic: its size, its concept, its cast of characters, its range of locations, its terrifying and exhilarating action sequences, and even its subtext, which is huge if fairly simple: those with greater power and wisdom than most must shoulder greater responsibility than most, and their not wanting to is basically irrelevant (not that they may necessarily have a choice in the matter).

This is big stuff all the way through, a colossal struggle between two born-to-it masters of their trade, neither of whom will ever take a backward step because they know no other way, and all played out against the majestic canvas of Europe and the Middle East in the age of wide-ranging espionage and terrorism.

On this basis alone, it might be understandable if some readers were put-off exploring this novel any further, perhaps suspecting an all-too-familiar mishmash of James Bond and Jason Bourne. But that would be an error, because I Am Pilgrim is an astonishing, multi-layered tale of conflict and belief, which is vivid, realistic and totally gripping for the entire duration of its 600 plus pages.

It’s no surprise at all that Hollywood has already got its hooks into it.

That isn’t to say that it hasn’t come in for criticism in certain quarters. The sheer length of the book has been described as OTT, while its excessive detail and numerous side-stories have been called self-indulgent and time-wasting. But I take strong issue with that. Despite the length of I Am Pilgrim , the pace never flags, the story never sags, and the suspense is overflowing – Hayes’s writing style is not exactly stripped down, but it makes for a fast, easy read, and I got through the whole novel in three days (in which case, a book can surely be as long as it wants to be).

Likewise, I have no truck with the argument that I Am Pilgrim is a lesson in what might happen if the US isn’t much more interventionist and belligerent in its overseas policies, and more willing to play dirty when it comes to espionage. Unfortunately, we do exist in an age of relentless terrorism, so while it could be argued that this book is alarmist in its tone, it’s a thriller – so it’s supposed to be, and it’s hardly telling us that something terrible could happen which we haven’t already imagined for ourselves. But to call that a demand for much more bullying and rule-breaking by the intelligence services is no more applicable than it would be to Bond movies or superhero comics in which the lead characters ignore almost every rule of law in their pursuit of megalomaniac villains.

Which brings us onto the characters, themselves. Pilgrim as an unusually vulnerable hero in the world of secret agents. And by that, I don’t just mean that he’s a guy with a faux conscience, one of these unconvincing characters who even in the midst of hardline law enforcement, is continually moved to remind us that he shares the peace-loving, socio-liberal values of the author. Pilgrim is much more rounded than that. Yes, he is regularly forced to make ruthless decisions, many of which he believes in, but he has genuinely always tried to perform his duty in a way that is least destructive, and much of his day-to-day life is overshadowed by memories of the lives he has taken. When he finds himself working side-by-side with the Saudi secret police, he is fascinated and appalled in equal measure by their casual disregard for human rights. Throughout the book, his desire to take an early retirement, to do something more useful with his life, is all-pervading, even though he strongly doubts that someone of his expertise would ever be allowed to. What this leaves us with is a very believable character, who authentically suffers, both physically and emotionally, and who, even though his ‘trust fund’ background has been knocked by certain picky critics – he’s been disparagingly referred to as ‘Bruce Wayne mark II’ – remains much more complex and intriguing than Batman, Bond or Bourne have ever been.

Meanwhile, as villain-in-chief (though he’s only one of many, in truth), Saracen is also a marvellous piece of writing. Rarely in western thriller fiction have I encountered a Middle Eastern terrorist, who – while it wouldn’t be true to say we sympathise with – we understand as much in terms of his motivations. Saracen’s transformation into a fanatic is a slow, painful process (and we accompany him much of the way), during which the seeds of fundamentalist hatred are not so much sewn into him, as hammered, by countless cruelties and injustices which any rational person would yearn to put right. It’s very easy in our world to dismiss jihadi grievances as an overblown excuse for out-and-out wickedness, but after reading I Am Pilgrim , you’ll think as the hero does: know your enemy – and know him well, or risk paying a deadly price.

I have no hesitation in declaring I Am Pilgrim one of the best espionage thrillers I’ve ever read. It’s got everything: action, suspense, intrigue, mystery, villains you love to hate and heroes you are rooting for every inch of their breathless journey. An amazing novel.

As I mentioned before, Hollywood is already developing I Am Pilgrim, and in fact – or so the rumour-mongers insist – may even be planning to launch it as the pilot for a brand-new franchise. Ordinarily, that would render any fantasy casting by me completely pointless, but I’ve looked around online, and I haven’t seen a cast-list yet, so as usual, I’m going to be bold (stupid?) enough to suggest my own:

Pilgrim – Edward NortonSaracen – Murat YildirimDet. Leyla Cumali – Beren SaatLt. Ben Bradley – Denzel WashingtonMarcie Bradley – Angela BassetDavid ‘Whispering Death’ McKinley – James WoodsIngrid Kohl – Alexandra DaddarioCameron Dodge – Evan PetersBattleboi – Eric StonestreetPresident James Grosvenor – Stephen Tobolowsky Bill Murdoch – Paul GiamattiDr Sydney – Bryan Browne

Published on January 14, 2018 06:35

November 12, 2017

Rogues to gather in dark, dangerous north

One event of this year which I have been anticipating more than many others is now almost upon us.

It is HULL NOIR, a celebration of northern crime writing, which I’m delighted and flattered to be participating in as chair of one of the panels. There have been Hull Noir events throughout this month, but it really gets going on the weekend of November 17-19. More about that in a few paragraphs, though it sets the tone for this week’s post overall, because today I am going to be discussing crime fiction that is both written and set right here in what used to be considered the Dark Half of England ... for which reason I probably couldn’t pick a better novel to review and discuss this week (in my usual forensic detail, I think you’ll find) than one of the original slices of urban Brit grit, Ted Lewis’s seminal JACK’S RETURN HOME, aka GET CARTER.

Again, more about that shortly – as always, you’ll find that review at the lower end of today’s post.

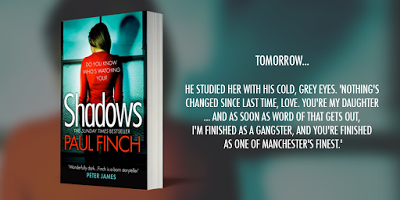

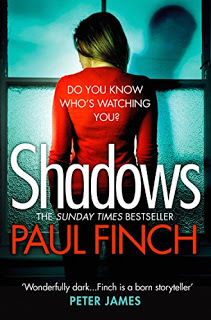

Before we get to any of that, but still on the subject of northern crime, I’m very happy to reveal that

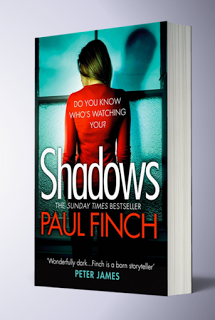

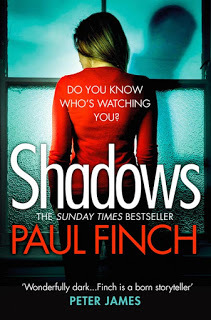

SHADOWS

, the second installment in my series of Lucy Clayburn novels, will only be 99p in ebook form from now until the end of this month.

Before we get to any of that, but still on the subject of northern crime, I’m very happy to reveal that

SHADOWS

, the second installment in my series of Lucy Clayburn novels, will only be 99p in ebook form from now until the end of this month.SHADOWS is every inch a northern crime novel, because, whereas my other main crime-fighting character, Mark Heckenburg, though a northerner by origin (born in the fictional Lancashire town of Bradburn, 17 miles outside Manchester) has a remit as a homicide detective to travel the whole of England and Wales, Lucy Clayburn ( STRANGERS was her first outing) is an inner-Manchester girl, and her home borough and workplace (the again fictional Crowley) is located somewhere between Wigan, Bolton and Salford, which makes it the absolute epitome of the industrial Northwest.

In the last book, as a uniformed officer, Lucy went undercover as a prostitute to try and catch a female sex killer of men, and in this new one, as part of the elite Manchester Robbery Squad, she embarks on the pursuit of a band of gun-toting robbers, who aren’t just causing horror and fear because of their crazy cowboy antics – they will shoot anyone for the slightest reason – but who, as they are mainly targeting the underworld, look likely to cause a major gangland war.

So there we are, if you’ve got an e-reader, and you haven’t yet got on the Lucy Clayburn train, now is your chance … and for the bargain basement price of 99p.

I’ll say no more on that subject, because now onto HULL NOIR .

From Craphouse to Powerhouse

Associated with the Hull 2017 UK City of Culture event, HULL NOIR looks set to be one of the major crime literature festivals of this year, so it was a real honour to be asked to get involved. The stars of the show are undoubtedly Martina Cole, Mark Billingham and John Connolly – and they’ll all be playing significant roles. Martina will be celebrating the 25th anniversary of her first published novel, Dangerous Lady, in the company of top crime critic, author and aficianado, Barry Forshaw, while Mark and John will be contemplating the worst and best of their careers with Daily Telegraph crime critic, Jake Kerridge. But in addition, there some amazing panels lined up for next weekend.

Check these out, just as a sample (because there are many others too):

On Sleeping with the Fishes, Nick Quantrill, David Mark, Lilja Sigurdardottir and Quentin Bates will be discussing the style and influence of Hull and Iceland as locations and inspirations for crime writing.

On Getting Carter, Ted Lewis and the Hard Boiling of British Crime Fiction, Howard Linskey, Russel McLean, Sean O’Brien, Andrew Spicer and Nick Triplow will chat about the influence of American-style hardboiled crime writing on the British school.

In Brawlers & Bastards, Steph Broadribb, Craig Robertson, Mick Herron and Harry Brett will debate the genre’s hardmen, and look at how crime writers have made antiheroes from some of the most reprehensible characters.

But the panel I’m most looking forward (me being biased, this being my own), is From Craphouse to Powerhouse, on which I’ll be joined by northern crime luminaries, Liverpool’s Luca Veste, Newcastle’s Danielle Ramsayand Glasgow’s Jay Stringer, to kick around the subject of crime fiction along the M62, the noisy but straight-as-an-arrow motorway which, running as it does from Merseyside on the west coast, through Manchester, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and finally arriving in Humberside on the east coast, is often seen as drawing a straight line through the very heart of the old smoky, sooty north.

We’ll be talking about all kinds of crime-related northern stuff, I imagine, from industrial might to post-industrial decay, from the numerous terrible murder cases in this part of the world that might have influenced us, to the development of organised crime in our vast inner city areas now rendered dark and desperate by unemployment, and to the emergence from this chaos of hard-bitten northern heroes, like Veste’s Murphy and Rossi, like Ramsay’s Harri Jacobs, like Stringer’s Sam Ireland, and, if I say so myself, like my own Lucy Clayburn and Mark Heckenburg, all of whom, though they’re not gangsters per se, (Hell, some of them are actually cops!), whether intentionally on our part, or subliminally, have taken a leaf out of Jack Carter’s ‘Don’t Argue’ playbook.

We’ll be talking about all kinds of crime-related northern stuff, I imagine, from industrial might to post-industrial decay, from the numerous terrible murder cases in this part of the world that might have influenced us, to the development of organised crime in our vast inner city areas now rendered dark and desperate by unemployment, and to the emergence from this chaos of hard-bitten northern heroes, like Veste’s Murphy and Rossi, like Ramsay’s Harri Jacobs, like Stringer’s Sam Ireland, and, if I say so myself, like my own Lucy Clayburn and Mark Heckenburg, all of whom, though they’re not gangsters per se, (Hell, some of them are actually cops!), whether intentionally on our part, or subliminally, have taken a leaf out of Jack Carter’s ‘Don’t Argue’ playbook.As I say, HULL NOIR officially gets going this weekend, at the Britannia Royal Hotel, Hull. From Powerhouse to Craphouse starts at 11:30am on Saturday, November 18.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

JACK’S RETURN HOME

JACK’S RETURN HOME by Ted Lewis (1970)

It’s the late 1960s in Scunthorpe, and Jack Carter is coming home.

Jack, born and raised in the northern steel town, left home quite some time ago to make his fortune in London, and, being a handy lad and inclined towards pitiless immorality, he eventually found his place as a mob enforcer. Since then, Jack has done all kinds of awful things at the behest of his employers, East End racketeers, Les and Gerald Fletcher, and in so doing, has earned himself a real reputation. Quite often, though, he lets his heart rule his head. For example, the clandestine affair he is conducting with Gerald’s wife, Audrey, is very ill-advised. But even more so is this return to Scunthorpe.

Long estranged from his family, Jack has only two close relatives remaining: his older brother, Frank, and Frank’s daughter, 15-year-old Doreen. But now Frank is dead, killed in an apparent drink-driving accident. The police, or ‘scuffers’, as they are known locally, see nothing suspicious in this. Frank was a barman, after all, and he worked in a particularly rough part of a particularly rough town. However, he was not known to be an unstable character, and in fact, compared to his brother, was a clean-living citizen – and this is the point where Jack becomes curious, refusing to believe that Frank would have climbed into his car having consumed an entire bottle of whiskey.

Though he came north ostensibly for his brother’s funeral, he now begins snooping around, asking questions, and it soon arouses the attention and eventually the ire of a number of local underworld figures.

Chief among these is Scunthorpe’s own godfather, Cyril Kinnear, but there are others who are no less dangerous in their own way: overly ambitious rival gang-boss, Cliff Brumby, for example; not-so-tough-but-well-connected loanshark, ‘Steelworks Thorpey’; ex-teddy boy and pool-room bully, Albert Swift, who became an underworld go’fer; and the ultra sinister Eric Paice, an old enemy of Jack’s, who, though he works superficially as a chauffeur, is mainly valuable to the mob for his ability to seduce and/or snatch young girls from lives of respectability for futures in pornography and prostitution – and Jack soon suspects that this latter is the key to the mystery.

It is only 1968, and blue movies are still taboo, but there is a voracious demand for them on the underground circuit, particularly among those interested in the sex adventures of very, very young females.

Increasingly firm attempts are made to dissuade Jack from continuing his investigation, gentle persuasion gradually giving way to violence, initially directed against those around him, such as Frank’s old mate and fellow barman, Keith Lacey, and Jack’s attractive if earthy landlady, Edna Garfoot, but finally against Jack himself – by which time it is verging on the lethal.

Jack continues to resist, even when he receives direct orders from Gerald and Les, as delivered by a pair of London hitmen, the brutal Con McCarty and camp-as-hell Peter the Dutchman ... and this latter makes him even more suspicious. How is his own firm involved in Frank’s death? And what role does Doreen play? – she may only be 15 and an orphan to boot, but her name crops up increasingly and in ever more lurid circumstances.

The more Jack evades attempts on his life, the more unedifying truths he uncovers, and the more personal this becomes. Soon, it is one man against the combined forces of both the London and the Scunthorpe syndicates, from which point there is no going back …

It’s very difficult to disassociate the novel,

Jack’s Return Home

, from the seminal Michael Caine and Mike Hodges movie adaptation of 1971,

Get Carter

. In fact, later editions of the novel were republished under that very title. In truth, there are a lot of similarities, even down to certain lines of dialogue, but there are some differences too.

It’s very difficult to disassociate the novel,

Jack’s Return Home

, from the seminal Michael Caine and Mike Hodges movie adaptation of 1971,

Get Carter

. In fact, later editions of the novel were republished under that very title. In truth, there are a lot of similarities, even down to certain lines of dialogue, but there are some differences too.To start with, Caine, though a mesmerising screen presence in his heyday, was ‘ethnically wrong’ to play Jack Carter, who in the book is a displaced northerner rather than a Cockney. In addition to that, perhaps the most famous liberty the movie took was in its transposition of the story from Scunthorpe to the even more grimily picturesque Newcastle. That said, none of these are really major issues. Where both the novel and the movie are united is in their warts-and-all portrayal of an unforgiving British gangland, setting their narratives against dingy working-class backdrops, and underscoring them with a level of sleaze that has shocking power even today.

In regard to all that, Jack’s Return Home is the original slice of Brit grit, the novel that opened the door to countless generations of Brit-Noir fiction to follow, while Get Carter , the movie, in taking the X certificate as far as it could go, presented us with a serious, grown-up thriller that would usher in a new age of UK-set hard-as-nails crime movies, much the way The French Connection did in the States (without Get Carter , it is doubtful we’d have had Villain , The Squeeze , Sitting Target , The Sweeney or The Long Good Friday ).

But back to the novel.

In terms of negatives (and there aren’t many of these), Jack’s Return Home may have lost a bit of its authority in the 21st century simply because time and society have moved on. It’s probably true to say that Ted Lewis was never a wizard with words. He could create atmosphere for sure, but he was no poet. Most of the impact his book originally made stemmed from it’s in-yer-face style. And even today, everything I’ve just said notwithstanding, it’s a bit of an eye-opener to see such a stark, matter-of-fact depiction of a rough, tough town, with its depressing rows of terraced houses, its fiery backcloth of factories and steel mills, its backstreet pubs full of drunks and strippers, and its smoke-filled billiards halls where a single wrong word can get you into serious trouble.

I can only imagine the strength of this narrative back in 1968.

That said, Ted Lewis wasn’t ploughing a completely lone furrow even then. Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958) had already blazed a trail for blue-collar fiction, with its energised tale of a resentful tough-nut and the lives he either ruins or enriches (but mainly the former!) as he crashes selfishly through post-war Nottingham, while Barry Hines’s wonderful A Kestrel for a Knave (1968) focusses on an unwanted boy from a Barnsley council estate, and his doomed friendship with a hunting bird he rescued as an orphanned chick. In this regard, Ted Lewis’s great innovation was to take the ‘kitchen sink’ template, and pile on the villainy, creating a very difficult reality where near enough everyone is corrupt, including the police and local dignitaries, where eff-words are the norm, where heavy drinking and the use of casual violence are the mark of manliness, and women in particular are treated like dirt.

This latter is perhaps the part where Jack’s Return Home is really at odds with modern thinking. Because at the heart of this tale lies the underworld’s all new money-spinner: hardcore porn. And it’s porn of the sordid, seedy, homegrown variety, in which desperate, cash-strapped actors participate for peanuts, especially the women, and in which almost no age restriction is put on them – in fact, the younger the better.

An accurate depiction of a squalid world, perhaps, but the novel has dated generally in the context of its female cast, almost all of whom are tarts of a sort: Frank’s ex-wife, Murial (who had sex with Jack after getting drunk); Frank’s former girlfriend, Margaret; good-time girl, Glenda; and even middle-aged landlady, Edna, who happily sits across the room from her lodger, with legs apart so that he can see her stocking-tops (and later on gets brutally beaten, to which Jack is stingingly unsympathetic).

It’s no surprise that not everyone these days sings the novel’s praises.

Jack Carter’s character is itself ambiguous. Caine’s appearance in the movie caused a stir at the time, everyone’s favourite cheeky chappie turning hard and vicious in his quest for revenge, but in the novel there is barely a hint of a pleasant side to his personality. On occasion, he reminisces about his early youth – the last happy time he knew, we suspect – when he and Frank got on their bikes and explored the woods and wastelands on the outskirts of town. These are moving sequences and poignant reminders that even monsters once were children. However, later on things changed for Jack, possibly in response to Frank’s gentler nature: Jack idolised his older brother, but as they grew older, Jack came to revile Frank’s habit of turning the other cheek, feeling increasingy betrayed by it. As such, for the bulk of this novel, Jack is a coldly merciless figure. He doesn’t go at it shouting and swearing, because he’s got nothing to prove – all the hoods in Scunthorpe know who he is, and most of them fear him. Even in casual conversation, you suspect it’s only the calm before the storm.

A staple of ‘tough guy’ fiction these days, I suppose Jack was one of the very first who you could say ‘didn’t start fights, but certainly finished them’.

So successful was Jack’s Return Home , that Ted Lewis wrote two additional Carter novels afterwards. But with his sad and premature death at the age of 42, the series ended there. Even so, he created an iconic character in the annals of British crime fiction, one who’s been copied many times since but has rarely been equalled, and set him in a world long lost but utterly unforgettable (even if mostly for the wrong reasons).

I’m in the habit of ending these book reviews with some fantasy casting, putting forward a ensemble of actors who I feel would be perfect in the roles. But given the two major movie adaptations that Jack’s Return Home already has in the bank – the totally awesome Get Carter (1971), and the significantly less awesome, Vegas-set Sly Stallone vehicle, Get Carter(2000), I don’t think there’s much point.

The cracking image topping today ’ s blog was taken in Newcastle during the filming of Get Carter (1971), and depicts Michael Caine and Ted Lewis. It currently graces the cover of GETTING CARTER, Nick Triplow’s new and amazing account of Lewis’s short-lived career. If anyone knows the name of the photographer, please tell me and I ’ ll be delighted to credit him.

The image at the top of today ’ s book review is the original cover art, as used by Michael Joseph on the first edition of the novel.

Published on November 12, 2017 13:22

October 22, 2017

It's here again: darkness, devilry and dread

The horror … the horror …

The horror … the horror …

Yes, we’re in the final run-up to Halloween, and so this week I’m going to take a brief break from talking about my new crime novel, SHADOWS, in order to celebrate the season of ultimate darkness.

I’m going to do this on three fronts: firstly, as a horror story writer myself (in my spare time, these days), by focussing on several scary story collections and anthologies which you need to be getting your teeth into at this time of year; secondly, by presenting a gallery of what I consider to be the 25 BEST HORROR NOVEL COVERS EVER; and thirdly, by reviewing and discussing in my usual forensic detail S.L.Grey’s spine-chilling THE APARTMENT – as always, you’ll find that review at the lower end of today’s post.

Books to read

One thing I always love about the waning of the year is the inevitable association it brings with eerie stories. I’m not going to prattle too much about how the oncoming cold and darkness and the dying of the land each autumn brought fear and concern to our ancient ancestors, who imagined that this was due to the presence of witches, goblins and other evil entities, and so in turn sought to commune with their own spirits to guarantee the timely return of the sun – but it’s a common belief among anthropologists that we still live with at least one result of this today: an increased awareness of and interest in spooky stories in the period between (and including) Halloween and Christmas.

Anyway, without more ado, if you share that interest and awareness, and you’re so inclined, why not check out some of these books?

Initially, I’m going to do a bit of self-pimpery. As I said, I’m no stranger to writing horror stories, myself. There isn’t enough space here to go back through my entire short story bibliography (and I doubt anyone reading this would have the patience for that anyway, and rightly so), but here are a couple of titles that might be of interest.

DON'T READ ALONE

was published in 2013, and features, among other things, an embittered writer who accidentally invokes the spirit of the Green Man, a cop whose determination to locate a missing child takes him into a nightmarish underground complex, and a bunch of marooned holiday-makers who are menaced by an ancient, oceanic beast ...

DON'T READ ALONE

was published in 2013, and features, among other things, an embittered writer who accidentally invokes the spirit of the Green Man, a cop whose determination to locate a missing child takes him into a nightmarish underground complex, and a bunch of marooned holiday-makers who are menaced by an ancient, oceanic beast ...DARK WINTER TALES is a more recent title, dating to 2016. In this one, again among other stuff, a housing estate is terrorised by a strangler with seeming inhuman powers, students visit a haunted house where, whatever happens, you are never supposed to look behind you, and the mother of the last man hanged in England becomes obsessed with an executioner’s dummy.

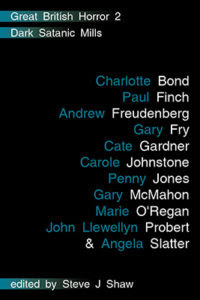

I also have a personal interest in GREAT BRITISH HORROR 2: DARK SATANIC MILLS, featured at the top of this column, which is a relatively recent title – September, 2017 – published by the excellent Black Shuck Books and edited by the indefatigable Steve Shaw. You don’t need to look too far beyond the list of contributors on the cover (again, check the top of this blogpost) to know you’ll be getting quality, but with authors like Carole Johnstone, Gary McMahon, John Llewellyn Probert and Angela Slatter, can you really afford to miss it?

On the subject of anthologies, I also want to mention

NEW FEARS

, also a recent publication, as edited by a good friend of mine and a top writer in his own right, the legendary Mark Morris. This title is a particularly important publication for horror fans, as it could well mark the commencement of a new, annual, high quality horror antho series, something we’ve been sorely lacking in recent years. Again, check out some of the stars on the contents list, and just listen to the titles of the stories they’ve written: The Boggle Hole by Alison Littlewood … The Embarrassment of Dead Grandmothers by Sarah Lotz … The House of the Head by Josh Malerman ...

On the subject of anthologies, I also want to mention

NEW FEARS

, also a recent publication, as edited by a good friend of mine and a top writer in his own right, the legendary Mark Morris. This title is a particularly important publication for horror fans, as it could well mark the commencement of a new, annual, high quality horror antho series, something we’ve been sorely lacking in recent years. Again, check out some of the stars on the contents list, and just listen to the titles of the stories they’ve written: The Boggle Hole by Alison Littlewood … The Embarrassment of Dead Grandmothers by Sarah Lotz … The House of the Head by Josh Malerman ...Lastly, here’s a particularly relevant title. Adam Nevill is a another close friend of mine, and another incredible writer – yes, I’m in real name-dropping mode today! – but he’s probably best known at this moment for the current cinema adaptation of his bone-numbing novel, THE RITUAL .

However, of equal interest to dark fiction fans should be his first collection of short stories,

SOME WILL NOT SLEEP

, which, trust me, contains some true fictional nightmares. I defy anyone to read stories like Where Angels Come In, The Original Occupant, Yellow Teeth and Pig Thing, and to sleep easily for the next few nights.

However, of equal interest to dark fiction fans should be his first collection of short stories,

SOME WILL NOT SLEEP

, which, trust me, contains some true fictional nightmares. I defy anyone to read stories like Where Angels Come In, The Original Occupant, Yellow Teeth and Pig Thing, and to sleep easily for the next few nights.But don’t take my word for it … investigate these titles out for yourself.

*

One of the joys (or agonies) of being an author is that first moment when you get to see the cover allocated to your latest book. You don’t always like them; appreciation of art is a subjective thing, of course. But just because you don’t like your latest jacket, that doesn’t mean others won’t, or that it isn’t actually fantastic. However, throughout the history of published fiction there have occasionally been book-covers so jaw-dropping that no serious person could ever do anything other than take a big, awe-stricken step backwards on first seeing them.

And the horror genre is no exception.

So here, in no particular order, are THE BEST 25 HORROR NOVEL COVERS EVER (including one or two short story collections, because this is horror, and in horror, the short form really counts):

1. THE LURKER AT THE THRESHOLDH.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth (Panther, 1970)

Familiar Lovecraft territory from the start as Ambrose Dewart returns to his ancient ancestral pile in the heart of rural Massachusetts, only to uncover horrific revelations about his family’s past and their connections to ancient evil. Mostly written by August Derleth from scraps of original HP text (first published in 1945), this reprint cover still conveys the intense cosmic horror better than all others ...

2. KRONOS Jeremy Robinson (Variance, 2009)

Can’t really comment on the book as I haven’t read it yet, but anyone who’s even vaguely uncomfortable swimming with deep water beneath them, or who gets nervy thinking about the ocean abyss, how does this one look to you? It concerns a former Navy Seal who is determined to avenge the loss of his daughter by destroying a mysterious, colossal sea-creature ...

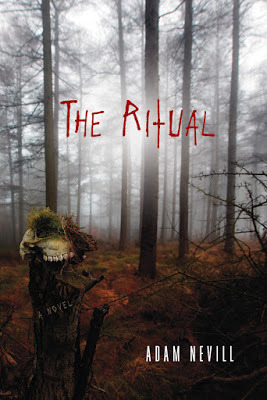

3. THE RITUALAdam Nevill (Pan, 2012)

Originally published in 2011, the reprint cover of this modern folk-horror classic still captures the atmosphere of the book better than any other. When four middle-aged English guys hit the wild backwoods of northern Sweden, they find themselves lost in a depthless primeval forest, filled with ancient mysteries and hideous relics, and with something ghastly in pursuit. Totally terrifying ...

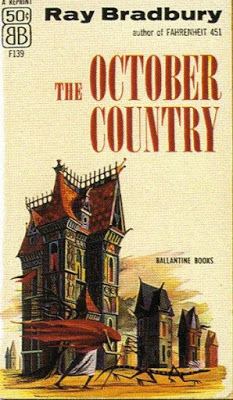

4. THE OCTOBER COUNTRYRay Bradbury (Ballantine, 1955)

A superb jacket to one of the ultimate horror collections, its otherworldly elements perfectly complementing the 1950s Avant-garde style to indicate that what you’re going to get here won’t just consist of the chilling and macabre, but will be liberally laced with weirdness and typical Ray Bradbury fantastica ...

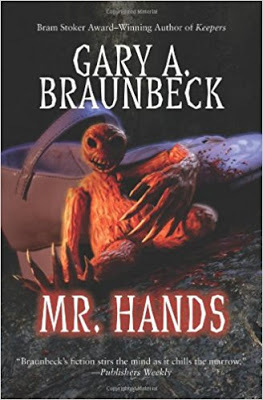

5. MR. HANDS Gary A. Braunbeck (Leisure, 2007)

This paperback edition put an unforgettable but very to-the-point cover on Gary Braunbeck’s third novel in the Cedar Hill series. For the uninitiated, Cedar Hill is a fictional blue-collar town in Ohio, where mysterious secrets are kept and unexplained forces wreak havoc. In this installment, Braunbeck gives his own unique take on the legend of the golem, as the jacket clearly shows ...

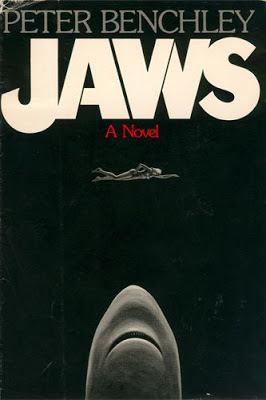

6. JAWSPeter Benchley (Doubleday, 1974)