Paul Finch's Blog, page 14

July 13, 2017

Hearts of darkness, both fictional and real

We’re talking gangsters this week, and by that I mean serious gangsters, nasty gangsters.

We’re talking gangsters this week, and by that I mean serious gangsters, nasty gangsters. Firstly, this is because I’ve now delivered my final copy-edit to HarperCollins for the next book in my Lucy Clayburn series, SHADOWS – and I even have a holding-jacket (left) to illustrate it – and gangsters, as you may know, are never far away when Lucy Clayburn’s on the case.

Secondly, it’s because this week I’ll also be reviewing and discussing Kevin Wignall’s excellent thriller, THE HUNTER’S PRAYER, which takes us along the periphery of organised crime rather than straight into the dark heart of it, and has some very intriguing and even moralistic things to say about the world of the contract killer.

Thirdly, when my last Heck novel, ASHES TO ASHES, was published, I wrote a guest-blog for the CRIMEBOOKJUNKIE website, in which I investigated the FIVE DEADLIEST CRIME SYNDICATES YOU MAY NEVER HAVE HEARD ABOUT. It appeared on the site on April 21 this year, and I’m now pleased to be reproducing it here (with one or two minor modifications to allow for the passage of time).

But more about that in a minute or two. For the time-being, back to Lucy ...

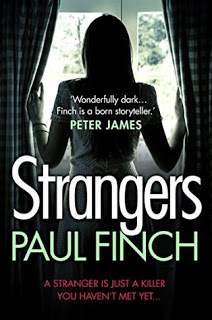

It’s difficult to talk about SHADOWS , and the heroine of the book, Lucy Clayburn, without giving away too many crucial spoilers about her own associations with the urban underworld. On the assumption that not everyone has at this stage read STRANGERS , my first Lucy Clayburn novel, I must therefore, by necessity, refrain from delving too deeply into the background of this tough lady cop from Manchester, though I still want to say a few things about the new book, which is due for publication on October 19 this year.

Since STRANGERS was published last spring, things have improved for Lucy Clayburn. In the first book, she was a uniformed copper in Crowley, Greater Manchester Police’s notorious November Division. She had a decade of service under her belt but was unlikely ever to get promoted (and in some parts of the job still invited ridicule) thanks to a major league foul-up several years earlier, which saw her kicked out of CID during her first week as a detective.

During the course of

STRANGERS

, many of these wrongs were naturally put right, and Lucy emerged at the end of it physically damaged but with her reputation massively enhanced. When

SHADOWS

starts, Lucy has resumed the role of detective constable and, though she’s only working Division, has continued to feel collars and impress people. She’s now regarded as one of divisional boss, DI Stan Beardmore’s best assets, and though she has been unwillingly partnered with the sloppy and outdated DC Harry Jepson, has regained all her old ambition. In particular, she has one eye on the elite Robbery Squad, who have relocated to Crowley from central Manchester, and are headed up by the legendary DI Kathy Blake and the fanciable DS Danny Tucker.

During the course of

STRANGERS

, many of these wrongs were naturally put right, and Lucy emerged at the end of it physically damaged but with her reputation massively enhanced. When

SHADOWS

starts, Lucy has resumed the role of detective constable and, though she’s only working Division, has continued to feel collars and impress people. She’s now regarded as one of divisional boss, DI Stan Beardmore’s best assets, and though she has been unwillingly partnered with the sloppy and outdated DC Harry Jepson, has regained all her old ambition. In particular, she has one eye on the elite Robbery Squad, who have relocated to Crowley from central Manchester, and are headed up by the legendary DI Kathy Blake and the fanciable DS Danny Tucker.But any road to advancement in this neck of the woods is going to be fraught with difficulty and danger. When a series of ultra-violent armed robberies commences, perpetrated by masked individuals wielding sub-machine guns (and not afraid to use them!), the scene is set for any copper in Crowley worth his/her salt to go out there and make a name for themselves. But there’s one problem with this. The unknown gang’s targets are exclusively underworld operations, and those mowed down by them are gangsters – so it’s only a matter of time before there is a massive and brutal retaliation …

And that’s it, sadly. If you want to know more, you’ve got to read the book. But don’t sweat; it’s not too far off. Just go and enjoy your holidays, and when you get home, it’ll only be a matter of weeks.

Lucy hits the shelves next October, and just to reiterate, the title of this next investigation is SHADOWS .

(And don’t get too attached to the jacket pictured above. As I said, it’s a holding-image, and will be replaced by the real one in due course; just watch this space).

*

And now, as promised, a fleeting glimpse into the infinitely more chilling world of real-life organised crime. Here, as it originally appeared on CRIMEBOOKJUNKIE, are:

THE FIVE DEADLIEST CRIME SYNDICATES YOU MAY NEVER HAVE HEARD ABOUT ...

Organised crime has been with us almost as long as we’ve had organised society.

From the crime collegia (thieves’ guilds) of Ancient Rome to the Viking chieftains of the Dark Ages, who only held off raiding when they were paid generous protection money; from the robber barons of the high Middle Ages, who ‘taxed’ travellers, defied their king and waged bloody feuds against each other, to the pirates and corsairs of the Spanish Main … the scourge of gangsterdom has been around for as long as we have.

From the crime collegia (thieves’ guilds) of Ancient Rome to the Viking chieftains of the Dark Ages, who only held off raiding when they were paid generous protection money; from the robber barons of the high Middle Ages, who ‘taxed’ travellers, defied their king and waged bloody feuds against each other, to the pirates and corsairs of the Spanish Main … the scourge of gangsterdom has been around for as long as we have. Its root-causes are often to be found in resistance to a pre-existing form of oppression. The Cosa Nostra, for example, was born in the mid-19th century, when feudal landlords objected violently to the annexation of Sicily by mainland Italy; in the US today, the Aryan Brotherhood, a far-reaching white supremacist organisation which dominates the American prison system, came together initially in defence of whites incarcerated alongside black and Latino gang-members.

Not that any of this excuses these vicious cartels, or the heinous behaviour they indulge in.

Many modern crime syndicates attempt to put a polite face on their activities. In the 1960s, the Krays’ firm in East London organised charity events and donated to good causes. Many senior mob figures in North America deny the Mafia even exists, and insist on posing as legitimate businessmen. But the reality in most cases is bloody violence, primarily among the syndicates themselves as they fight for control of the rackets.

We, of course, in the world of crime writing, find them utterly fascinating. Even those of us who don’t write or read crime fiction, are often captivated by the near-romance of these dark, dangerous but often suave and charming rogues.

We, of course, in the world of crime writing, find them utterly fascinating. Even those of us who don’t write or read crime fiction, are often captivated by the near-romance of these dark, dangerous but often suave and charming rogues. The names of their leading lights are recognisable the world over: Al Capone, Bugsy Siegel, Lucky Luciano, Pablo Escobar. In some cases, they are almost admired. It is often said that Chicago bootlegger, Capone, was merely providing a popular service to a thirsty city. Britain’s Great Train Robbers (though not gangsters per se) attained folk-hero status because of the daring heist they pulled.

But again, the reality of organised crime is often pitiless brutality. Between 2007 and 2014, at the height of Mexico’s so-called Dope Wars, an estimated 164,000 people were murdered. In January this year, a battle between two imprisoned drugs gangs in Brazil’s Manaus jail left over 60 dead, including many who were found decapitated. Capone himself, seen almost as a gentleman by modern standards, didn’t just order the St Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929, but was a former hit-man in his own right, and personally participated in the beating/shooting murders of three rivals.

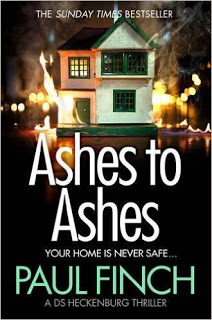

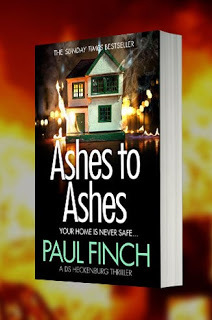

This kind of wild underworld warfare is very much the backdrop against which my most recent Heck novel,

ASHES TO ASHES

, is set. Though Heck is part of the Serial Crimes Unit, and primarily hunts lone killers, in this most recent book (published last April) he becomes involved in a horrific case at the centre of which a savage gangster war is being waged. In short, the bulk of the narcotics supply in the Northwest of England was once the sole fiefdom of Manchester kingpin, Vic Ship, but now a breakaway group under the leadership of a charismatic young gun, Lee Shaughnessy, is challenging his stranglehold on the post-industrial, drugs-dependent wasteland that is Bradburn (which lies midway between Manchester and Liverpool).

This kind of wild underworld warfare is very much the backdrop against which my most recent Heck novel,

ASHES TO ASHES

, is set. Though Heck is part of the Serial Crimes Unit, and primarily hunts lone killers, in this most recent book (published last April) he becomes involved in a horrific case at the centre of which a savage gangster war is being waged. In short, the bulk of the narcotics supply in the Northwest of England was once the sole fiefdom of Manchester kingpin, Vic Ship, but now a breakaway group under the leadership of a charismatic young gun, Lee Shaughnessy, is challenging his stranglehold on the post-industrial, drugs-dependent wasteland that is Bradburn (which lies midway between Manchester and Liverpool). What can only be described as hellish violence ensues, with a soaring body-count and some ghastly murder methods employed. To say more would be too much of a giveaway, but you don’t need to be a regular Heck reader to know that he throws himself headfirst into this blood-soaked chaos to try and get a result.

However, as ASHES TO ASHES - without doubt the most ‘gangstery’ of all my books - is still in the charts, and as I really don’t want to hit you with any more spoilers, I thought now might be an opportune time to look again at the real world of organised villainy, and pick out what I consider to be five of the deadliest crime syndicates operating today which you possibly don’t know about.

So, forget the Mafia (both the US and Italian versions), the Yakuza, the Triads, the Yardies. Here, in no particular order, are:

BARRIO AZTECA

BARRIO AZTECAOnce a prison gang, Barrio Azteca formed in El Paso in the 1980s, but have since made good in the cross-border drugs trade between Mexico and the US. Thanks to their unique geographic positioning, they are one of only very few transnational crime syndicates, members often holding both Mexican and US citizenship, which gives them a huge advantage over their drugs-smuggling rivals. They are also notoriously violent, and are responsible for dozens of killings on both sides of the border (though mainly in Ciudad Juárez, on the Mexican side) their preferred method being to beat and then burn to death their victims, sometimes in front of cheering crowds of gang-members. The group has been accused of carrying out full-scale massacres of rivals, by machine-gunning them to death in their prison cells (after being admitted by staff!), and on one occasion mowing down 16 innocent teenagers at a soccer party because ‘suspect characters’ were believed to be present.

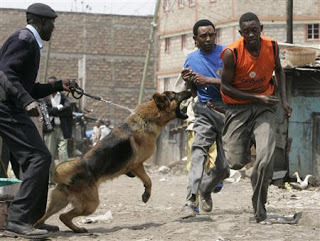

MUNGIKI

MUNGIKIA semi-religious organisation, Mungiki is seldom heard of outside its native Kenya, but inside the country they are a source of terror. With an anti-western ethos and strong indigenous African beliefs, they model themselves on the Mau Mau militia who resisted British colonial rule in the 1950s, but now are mostly known for organising crime in the slums of Nairobi, where protection racketeering and extortion of ordinary residents are their prime activities. Though considered by some to be on the wane, as recently as 2007 Mungiki sought to reinforce their authority with a wave of decapitations. In turn, Kenyan security forces have been accused of heavy-handedness in their response to Mungiki violence, and leaving many of the gangsters shot by the roadside. However, the counter-argument has been made that a large number of Mungiki deaths are just as likely to be the result of factional infighting among members, as they now believed to have split into rival camps.

NDRANGHETA

NDRANGHETAOne of several southern Italian cartels – indeed, occasional allies of the Sicilian Mafia and the Neapolitan Camorra – the Ndrangheta of Calabria are fast emerging as one of the pre-eminent criminal organisations in the world. Having initially behaved like old style bandits, in the early days they used kidnapping and blackmail to finance contacts with Colombian coke cartels, but these links have since proved very lucrative, putting the syndicate firmly in the big league. In fact, they are now believed to be among the world’s most successful drugs traffickers and money launderers, with an estimated annual revenue of $50-60 billion, and are even suspected of financing political corruption and infiltrating public offices, and not just in southern Italy, but in the north as well. In fact, Ndrangheta influence is now felt beyond Italy, in Northern Europe, the USA and Australia, where, though they still peddle drugs, they have diversified into arms smuggling and human trafficking.

SOLNTSEVSKAYA BRATVA

SOLNTSEVSKAYA BRATVAPerhaps the dominant force in the terrifying world of the Russian Mafia. Moscow-based, and strictly adhering to the normal Russian gangster code that all members must engage in regular fitness and weapons training, in effect turning themselves into a spec-ops of the underworld, the Solntsevskaya, though controlled by a central committee, are organized into warlike brigades and these into smaller but very mobile and highly aggressive ‘wolf-packs’. As such, they have no compunction about challenging rival mobsters, and have successfully extended their arms and drugs-trafficking, money-laundering, assassination and general racketeering businesses into the US and the Caribbean. They have a particularly firm foothold in Atlanta, where they are said to have taken on various other established groups and defeated them in battle. American sources say they are in cahoots with Russia’s Federal Security Service, but this has not been proved.

LOS ZETAS

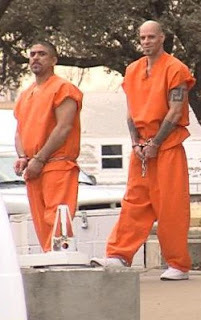

According to the US Government, Los Zetas are ‘the most technologically advanced, sophisticated, efficient, violent, ruthless, and dangerous cartel operating in Mexico’. An explanation for this can be found in their origins. During the 1990s, the group was formed by former special forces soldiers, who had deserted the Mexican Army looking for better pay. They found it working as muscle for the massive Gulf Cartel, and brought with them extreme mercilessness, but also high-tech weapons and the skills to use them. In 2010, again tired of taking orders, Los Zetas broke away to form their own syndicate. Despite internal instability, they are highly successful drugs traffickers, but are mainly notable for the staggering degree of violence they will use, having instigated numerous massacres of both rivals and civilians alike. Geographically, they are now the largest cartel in Mexico (controlling 11 states!), but their power extends far beyond their traditional homeland, both north and south.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE HUNTER’S PRAYER

THE HUNTER’S PRAYER

by Kevin Wignall (2015)

Carefree student Ella Hatto’s happy middle-class life ends horrifically one bright summer morning in Tuscany, where she’s on holiday with her boyfriend, Chris. First of all, back home in the UK, her father, mother and younger brother are murdered in their own home, executed by a skilled assassin. Next, she herself is targeted, caught up in a whirl of unexpected violence as a kill-team closes in on her, only to walk into a storm of bullets itself.

Unbeknown to Ella, a professional bodyguard called Lucas was hired by her successful businessman and part-time gangster father, and charged with shadowing her while she was abroad. Lucas, it seems, has stepped in at just the right moment, and gunned down the killers – but now he must whisk Ella and Chris away before the law arrives and starts asking awkward questions.

The two students are shaken to the core as their unlikely guardian moves them from one safehouse to the next, constantly trying to elude both the police and any further gunmen who might still be on their tail.

In due course, he finds sanctuary for them in the very last place he would normally have chosen: his own isolated and rather spartan villa in the foothills of the Swiss Alps.

As a former contract killer-turned-protector, Lucas is already a far cry from other characters of this ilk whom we may have encountered in different crime novels. He’s good at what he does, but he’s not cold-blooded about it. There is no granite hardness in Lucas, no pitilessness, no icy indifference to the pain of others. Okay, he’s not an especially warm character … but he does start warming to Ella. While Chris is simply frightened and increasingly resentful that he’s been dragged into this disaster, Ella – the real victim, who lost her family (whereas Chris merely lost his holiday!) – handles it better. She’s obviously grief-stricken, but she’s so innocent, so polite and yet at the same time so grown up in the way she deals with her terrible bereavement that Lucas can’t help but admire her and even be influenced by her.

The truth is that this ex-hitman is already, in a way, on the road to redemption. Though he’s still immersed in his murky world – he remains friendly, for example, with another much more callous killer, the likeable and yet utterly ruthless Dan Borowski – he basically wants out. He’s much happier to be a bodyguard than an assassin, but even then, his attempts to save the two youngsters take him far beyond the call of duty, a dedication to preserving their lives which stems not so much from his conscience, perhaps, but from a burgeoning desire to improve himself, a yearning to rejoin the civilised world (which gradual change of heart has already seen him develop an interest in the arts and literature).

Partly, this is down to his own domestic circumstances. His French girlfriend Madeleine, the one genuine love of his life, ditched him a decade and a half ago when she discovered what he did for a living, and ever since has denied him access to their daughter, Isabelle, who is now in her mid-teens; Lucas strongly desires to re-acquaint with the child, and can only hope and pray that she has grown up to be as balanced and sensible as Ella.

And yet here lies the deep irony in this unexpectedly philosophical story, because while Lucas’s initial interactions with Ella have encouraged him to reconnect with his estranged family, Ella is headed the other way.

Once safe in the care of her Uncle Simon, she becomes heir not just to her father’s wealth, but also to all his business dealings, even the nefarious ones, and as she works her way through them, trying to fathom out the identities of those who wanted her family dead, her grief transforms into slow-building rage, which, given that she’s now wealthy, no longer feels impotent. Very quickly, her attempts to rebuild her shattered world morph into an obsessive pursuit of revenge …

The Hunter’s Prayer – a revised version of For the Dogs (first published in 2004) – is not simply a murder mystery or an action thriller. If anything, it’s more of a parable. A metaphorical journey, if you like, into the ultimate futility of vengeance, and at the same time a lamentation at how salvation for some often seems to come at the price of damnation for others.

Unfortunately, I can’t discuss the unfolding narrative in too much detail for fear of giving away some quite remarkable twists in the second and third acts. Suffice to say that Kevin Wignall has done it again. The master of the thoughtful crime thriller presents us here with yet another potential high-octane scenario, and though he delivers the action plentifully, he asks questions of the reader throughout, even if only at a subliminal level.

You can tell where his real interests lie, because though we’re in the world of contract killers and organised crime here, we don’t go into huge detail about the criminal networks and illegal operations that provide the background to that. Nor do we investigate the creation of the hitmen themselves, neither assessing their warped psychology nor plumbing the hellish personal experiences that first put them into this line of work and equipped them with the necessary skills. Instead, the author is more focussed in the personalities of all his central characters as they stand now, their current mindsets, how they lead their everyday lives.

For example, we watch his hitmen blend easily into the rest of society when it suits them, we watch them go home at night and relax, we see them try to maintain their own codes of ethics even when they’re out on the job, and yet at the same time we’re acutely aware of the coping mechanisms they’ve needed to develop into order to endure the isolation of this strange, stilted existence; we recognise that they live on a mental knife-edge.

Lucas is to the forefront of this, not just because he’s the novel’s antihero, but because he’s actively undergoing change. It’s not that he’s necessarily sickened by the killing, it’s just that he’s tired of being an outsider, and when he encounters a genuinely pure person, who certainly looks as if she had a stable and promising life ahead of her, he is galvanised into fighting his way back to normality. This is certainly a cause we can root for, because we never feel that Lucas is actually evil. We can see that he’s damaged and alone, and though he’s done bad things, he’s done brave things too, so we want him on the side of right.

Much more of a challenge is the novel’s other main thread: the disintegration of Ella Hatto’s soul.

From the sweet child we met at the start of the book, she goes on to do horrible things – and again, Wignall, who remains non-judgemental throughout, wonders where we stand on this. Do we at least understand it, even if we don’t sympathise?

She’s suffered appallingly, and because of her innocent nature, only slowly does she come to realise what the massacre of her family actually means: someone she’s never even met (she assumes!) harboured such hatred of she and her people that they made a determined and expensive effort to have them all eliminated. So, is it surprising that, even in the light of her newly acquired wealth – because, and it’s hugely ironic, Ella has gained more financially from this atrocity than anyone else! – she now feels that her life has been ruined? How can she enjoy such wealth? How can she rest while this terrible offence against the Hatto name remains unanswered? And while Lucas has never encouraged this kind of thinking, she’s seen him in action; she now knows how effective a ruthless attitude can be – if you can finally right all wrongs (at least in your own mind) quickly and neatly, without waiting on the wheels of justice, which grind slowly at the best of times but you just know are not going to turn in your favour at all on this occasion, aren’t you justified in doing it?

It’s an interesting question. But another one would be – and again, the author asks us this – just how much leeway should a bad experience give you? Can it really forgive or even explain the complete erosion of all human feeling? And just because you’ve given up on the prescribed concept of right and wrong, and in fact have invented your own, does that mean the original concept no longer exists? Does that mean there’ll be no consequences? Don’t bank on it.

Be under no illusion, The Hunter’s Prayer is a very, very dark novel. But at 210 pages it’s a slim volume too, clearly and concisely written, and as such, it provides a quick, tense read, which, while it wouldn’t be true to call it enoyable - certainly not near the end, at which point it becomes utterly horrific - is more than a little bit thought-provoking.

As

The Hunter’s Prayer

has already been filmed – it was only released in the US last month – starring Sam Worthington and Odeya Rush – it makes another of my usual ‘this is how I would cast it’ interludes redundant. Suffice to say, I’m glad it made the big screen and am keen to see how it adapts.

As

The Hunter’s Prayer

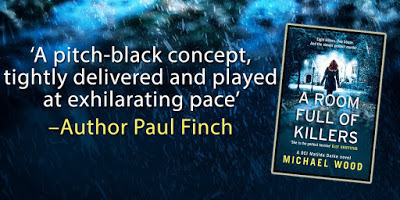

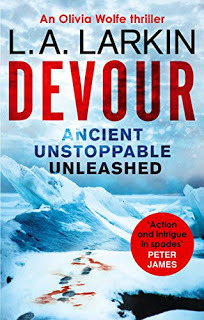

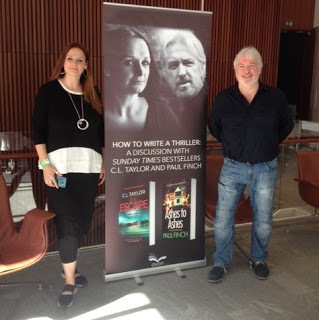

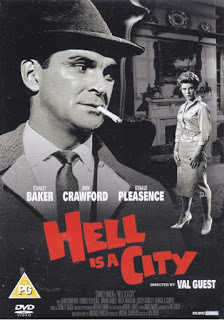

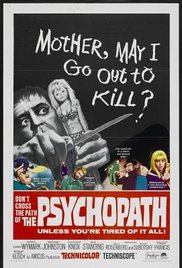

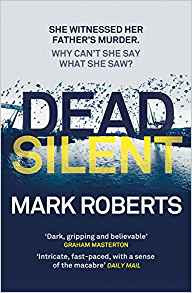

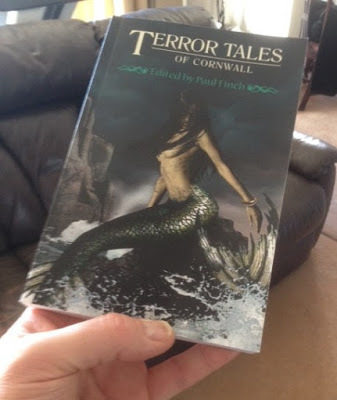

has already been filmed – it was only released in the US last month – starring Sam Worthington and Odeya Rush – it makes another of my usual ‘this is how I would cast it’ interludes redundant. Suffice to say, I’m glad it made the big screen and am keen to see how it adapts.Many thanks to all the various sources who’ve provided today’s images. They are, from the top down: Shadows (the holding-jacket only); Strangers; Ivar the Boneless, the most savage of all Viking warlords, as portrayed by Alex Hogh Anderson in the excellent TV series, Vikings; Al Capone; Ashes to Ashes; Barrio Azteca members on trial, pic by NewsWest9; Mungiki suspects menaced by police dogs, pic by Antony Njuguna; an Ndrangheta weapons stash, pic by AP; this one speaks for itself, pic from Voices from Russia; the Zetas, pic from mySA (San Antonio news); The Hunter’s Prayer - in book form; and in movie form.

Published on July 13, 2017 07:47

June 27, 2017

Following in the footsteps of a true legend

I hope you don’t mind me adopting a bit of a personal tone this week. But today is the tenth anniversary of my late father, Brian’s death, and I just want to take the opportunity to honour his memory with a quick retrospective on a life well-lived.

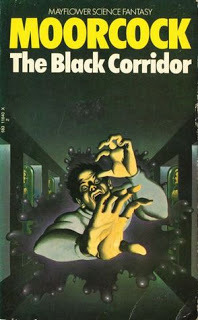

If you’ve tuned in for my review of Michael Moorcock’s sci-fi/horror classic, THE BLACK CORRIDOR, never fear – as usual, you’ll find it towards the end of this post. Though I chose that one specifically for today, as Moorcock was one of so many great authors that my father put me onto.

In fact, when you get down there, check out the amazing cover-image. That was one of many startling book jackets which, when I was knee-high to a grasshopper, I first saw on my father’s shelves, and which intrigued me so much that, when I was finally old enough, I had no real choice other than to investigate the world of dark and mysterious fiction.

Before we get into that, though, a few quick words about my Dad ...

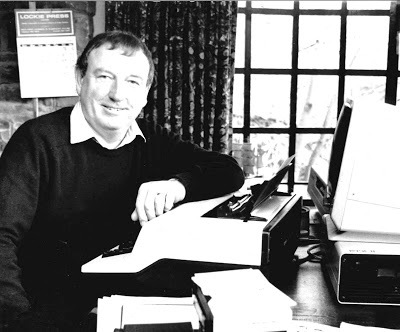

James Brian Finch (pictured above in the 1980s) passed away 10 years ago today, after battling a long and debilitating illness. He was only 70 years old, which I’m sure most of us would agree is no great age these days. But the things he achieved in his life cannot be estimated in a few short sentences.

Though a descendent of Charles Dickens, he was of relatively humble origins, born the son of a coal-miner in Wigan in the 1930s, at the very time when George Orwell was still plodding its sooty, cobbled streets. This was a dour time and place, and hardly conducive to personal ambition. As such, with nothing to boast about in terms of school qualifications, he grew to young manhood after a what could only be construed as an unremarkable early life.

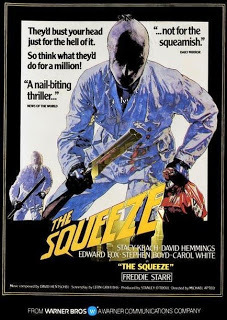

However, it was during his time in the military when he became interested in drama, writing routines and performing songs and comedy sketches for a concert party in the RAF. Though on returning to Civie Street, he secured regular work as a journalist and press officer, he remained fascinated by the stage and screen, making his first TV sale to The Wednesday Play in 1966, and then contributing episodes of Z Cars (pictured) and Coronation Street, finally becoming one of the latter show’s leading writers, penning over 150 scripts during the 1970s and 1980s, but at the same time branching out across the entire spectrum of British television.

However, it was during his time in the military when he became interested in drama, writing routines and performing songs and comedy sketches for a concert party in the RAF. Though on returning to Civie Street, he secured regular work as a journalist and press officer, he remained fascinated by the stage and screen, making his first TV sale to The Wednesday Play in 1966, and then contributing episodes of Z Cars (pictured) and Coronation Street, finally becoming one of the latter show’s leading writers, penning over 150 scripts during the 1970s and 1980s, but at the same time branching out across the entire spectrum of British television. Probably one of the most successful screenwriters of his generation, my Dad’s career eventually came to span four decades, and saw him writing for an astonishing array of popular and ground-breaking TV, hitting every kind of genre and subgenre there was.

Probably one of the most successful screenwriters of his generation, my Dad’s career eventually came to span four decades, and saw him writing for an astonishing array of popular and ground-breaking TV, hitting every kind of genre and subgenre there was. The many, many programmes he wrote for included The Tomorrow People, General Hospital, The Brothers, Public Eye, Hunter’s Walk, The Chinese Puzzle, The Squirrels, Bergerac, Juliet Bravo, The Gentle Touch, Hetty Wainthrop Investigates, Heartbeat, The Bill, and All Creatures Great and Small.

In the end, it all culminated in his winning a BAFTA in 1998 for his TV adaptation of Michelle Magorian’s Goodnight Mr Tom, though the picture right was taken a year or so after that latter event, when I won the British Fantasy Award for my first short story collection, Aftershocks, and we thought we’d compare our gongs.

In the end, it all culminated in his winning a BAFTA in 1998 for his TV adaptation of Michelle Magorian’s Goodnight Mr Tom, though the picture right was taken a year or so after that latter event, when I won the British Fantasy Award for my first short story collection, Aftershocks, and we thought we’d compare our gongs.(Apologies about the mullet – my Dad, as you can see, always kept his hair sensibly short).

But it was quite a world that my Mum, my three sisters and I experienced. All the latest and juiciest TV gossip was aired around the kitchen table. It wasn’t unusual to pick up the phone in our house, and find Frankie Howerd on the other end of it, or John Thaw, or Robert Hardy.

Dad was the most astounding inspiration for all kinds of reasons. Though he’d left school with few grades, he’d made up for that over the years by self-educating, which meant that I grew up in a home where enquiry was always good, learning was prized, art and civilisation were hugely appreciated, and where a constant stream of books, films and plays were recommended to me. And it wasn’t just the darker material that I’d go on to make my own career in – though Dad was a big fan of that stuff – but also the classics of our age.

Stratford-upon-Avon became our second home. It was one of my Dad’s favourite places, and more times than I can count, he took us there to watch some of the greatest plays ever written performed at the highest level.

Is it inevitable that I always sought to emulate him, that he was, quite literally, everything I wanted to be? I’m certainly grateful that he lived long enough to see my early output as a professional – my own episodes of The Bill (shortly after I left the police for real), my various stories as they appeared in anthologies and magazines, and the stage production of a radio play I wrote in 1991 called Cross and Fire. Alas, he wasn’t around when what I classify as my real success – my cop thrillers, the Heck and Clayburn novels – came along. But at least I managed to get two shared credits with Dad, even though they came after we’d lost him.

In 2008, a year after he died, I wrote a horror novella, Gingerbread, from an outline he himself had penned two decades earlier for a TV thriller which never got made (I think the series it was originally proposed for was Hammer House of Horror), and it was published by Pendragon Press. I was delighted to finally see it in print, and even more so to see mine and Dad’s names together on the by-line (many thanks to Chris Teague for getting it out in time for Fantasycon, that year).

A slightly bigger deal than this came with the 2010 full-cast audio Dr Who drama, Leviathan, which I wrote for Big Finish. It was part of the ‘Lost Stories’ series and I adapted it for audio from a Dr Who serial of the same name, which my Dad wrote in 1984 – it had reached the rehearsal stage back then, but was finally hacked from the schedule as it was deemed too expensive for production.

There is a cute little story connected with Leviathan, if you’ve got half a second ...

My writing career was at a really low ebb in 2009; The Bill was several years behind me, and Heck was still far in the future. I hadn’t earned much for two or three years. When I found out that Big Finish were looking for the Lost Stories – i.e. Dr Who serials that almost got made for TV, but for various reasons weren’t – I offered it to them on the condition that I could be the one to write it.

My writing career was at a really low ebb in 2009; The Bill was several years behind me, and Heck was still far in the future. I hadn’t earned much for two or three years. When I found out that Big Finish were looking for the Lost Stories – i.e. Dr Who serials that almost got made for TV, but for various reasons weren’t – I offered it to them on the condition that I could be the one to write it. The problem then was that I couldn’t find the original script anywhere.

I turned my Mum’s house upside-down and we uncovered scripts from every era it seemed, but there was no trace of Leviathan. I knew I’d seen it somewhere, but there was no sign of it when I needed it most, and obviously, if I couldn’t find it, I couldn’t proceed with the deal. After several days, I was sitting in my office at home in near-despair, thinking I was going to have to send back word – when I suddenly spotted a buff folder on a bottom shelf, covered in dust. I don’t know what drew my eyes to it, but it struck me as odd that I had no clue what was inside there.

Tentatively, I dusted it off and opened it – and there it was, the original Leviathan by Brian Finch, yellowed and dog-eared with age, but minus only two of its pages.

The project went ahead as planned: I adapted it for Big Finish Audio, and everyone involved was fantastic, Colin Baker and Nicola Bryant going at it full tilt as I sat in a sound-proofed booth down at the Ladbroke Grove studio and enjoyed one of the proudest moments of my career. We got a great Dr Who product out, which did very well in the shops – and yes, I again got that all-important shared credit with my Dad.

The really uplifting bit about that little episode, though, is that it somehow turned the tide in my career. Up until Leviathan, I’d struggled to make any kind of notable impact. Ever since Leviathan, things have gone ... well, let’s just say that I’ve never been happier professionally.

It’s yet another reason to thank my late-father, and another memory to add to a whole batch of joyful memories that he left for us.

Yes, it’s now ten years since he passed, and though it’s true that you never get used to losing a cherished one, he left such a legacy of love, friendship, warmth and genuine, knowledgeable guidance – and of course that crucial inspiration for me – that I’ve never really felt as if he’s gone. I miss him achingly. Who wouldn’t? But he was such a great guy, who made such an enormous impact on the lives of all those who met him that I’m cosy in the sense that he’s still somewhere close by, and feel confident that his benign presence will never, ever fade.

Yes, it’s now ten years since he passed, and though it’s true that you never get used to losing a cherished one, he left such a legacy of love, friendship, warmth and genuine, knowledgeable guidance – and of course that crucial inspiration for me – that I’ve never really felt as if he’s gone. I miss him achingly. Who wouldn’t? But he was such a great guy, who made such an enormous impact on the lives of all those who met him that I’m cosy in the sense that he’s still somewhere close by, and feel confident that his benign presence will never, ever fade.(Many thanks to the local press, I assume the Wigan Evening Post, for the great picture at the top. Sorry guys, I’m not sure which particular snapper took this one, as it was an awful long time ago, so the credit goes to all of you).

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE BLACK CORRIDOR

THE BLACK CORRIDOR

by Michael Moorcock (1969)

In a future of violence and decay, uncompromising businessman, Ryan, foresees no hope either for himself or for his family. In the midst of social disintegration, societal breakdown, ecological disaster and the impending slaughter of a nuclear war, and with all his close relationships – both personal and business-related – severed, he finds he has no option but to steal an interstellar spaceship, the Hope Dempsey, load it with the handful of people left on Earth whom he actually cares about, and set off for Munich 15040, a habitable world in the constellation of Ophiuchus.

The journey is a short one in cosmic terms – a mere six light-years – but it’s a massive undertaking for human beings. Even so, under his stewardship, Ryan feels they can make it. Once safely landed on their new home, he is confident they’ll be able to start again, get back to basics, live a simple, clean life, and in the process reformat humanity.

At least that’s the plan, but in reality it isn’t going to be anything like so easy.

In The Black Corridor (which term actually refers to space itself), once you’re out there among the stars there is no sense of the wonder and mystery that science fiction readers of earlier decades had been led to imagine. Instead, it is a cold, dead void, a soulless vacuum in which the chances of dying an ugly, lonely death are very high indeed – and in fact this is the note we come in on as the novel starts. Check out this immortal opening passage:

Space is infinite. It is dark. Space is neutral. It is cold.*Stars occupy minute areas of space. They are clustered a few billion here. A few billion there. As if seeking consolation in numbers. Space does not care.*Space does not threaten. Space does not comfort. It does not sleep; it does not wake; it does not dream; it does not hope; it does not fear; it does not love; it does not hate; it does not encourage any of these qualities. Space cannot be measured. It cannot be angered. It cannot be placated. It cannot be summed up. Space is there.*Space is not large and it is not small. It does not live and it does not die. It does not offer truth and neither does it lie. Space is a remorseless, senseless, impersonal fact. Space is the absence of time and of matter.

(If you feel you recognise that extract from the annals of rock music, you’re correct – it was utilised on Hawkwind’s classic 1973 album, Space Ritual ).

The voyage itself is a nightmarish experience. With the rest of his crew in cryogenic stasis, Ryan alone must run the ship, check the computers, continue to monitor their course, and all the while he talks to no-one but the spaceship’s log, and, outside, sees nothing but the vast and frozen emptiness. Inevitably, his mind begins to wander and, whether he likes it or not, he commences reliving, in vivid flashback, the terrible events on Earth leading up to their departure, at the same time mulling over his own achievements, or the lack of such. For Ryan, it seems, is not a particularly nice guy. It may be that now he heroically leads his suffering people to a kind of promised land, but during his time on Earth he was ruthless, unprincipled, vain and deceitful. Wherever he went, he left damage.

The memories of this torture him unmercifully, but no more so than the sheer, mind-boggling solitude of his limitless journey. Eventually he begins to hallucinate, to fantasise … quickly losing track of what is real and what isn’t, and at the same time infecting the reader with similar doubts.

Did any of these events that Ryan flees from actually happen?

Who is Ryan?

Why is he here on this seemingly deserted spacecraft?

Where is he really headed to? Does that place exist?

And perhaps more frightening still, is it possible that he isn’t genuinely alone? Could there be someone else on board, someone who seemingly is not lying in suspended animation? Ryan certainly finds evidence of this, but who could this interloper be, why does Ryan never see them, and what is their purpose?

You just know, without needing to be told, that none of this is going to end well …

The most obvious thing you can say about The Black Corridor , which is only 126 pages in length, (and unofficially was co-written by Moorcock with his then-wife, Hilary Bailey) is that it was intended as a short, sharp shock to the blasé sci-fi buying public of that era.

It’s a classic example of the ‘new wave’ subgenre popular at the end of the 1960s in that it prophesied a dystopian future of warring, hate-filled tribes rather than an age of technological imperiousness; in that it was written in a consciously stripped-down style; in that it used ripe language and was frank in its depictions of human violence and sexuality – but also in that it was political (even anarchic) in its subtext and scathing about mankind’s reckless mismanagement of the Earth.

But don’t go away with the impression that this novel is an essay or a polemic. It’s certainly experimental in parts. There is curious and often distracting use of ‘alternative’ typography, and there are sections when we are subjected to technical printouts and random streams of consciousness rather than coherent narrative, but despite these tricks – which are a bit irritating, if I’m honest – this is still a rattling good tale, especially if you like your fiction off-the-wall.

Just be warned – there are no space monsters in this novel, no ray-guns. Though that doesn’t mean it isn’t eerie and fascinating, not to say on occasion pretty damn frightening. The growing sense of menace stems entirely from Ryan’s rapidly worsening predicament: the endless isolation of his headlong flight, the uncertainty of what might lie at its end, if anything, and his gradual but inevitable meltdown, which of course perfectly mirrors the meltdown back on Earth, for that too was fermented by ignorance and folly.

Some have accused The Black Corridor of dating badly, of being a typical exercise in ’60s psychedelia and laced with the sort of woolly-headed hippy-think we’d these days scoff at as pseudery. But on reflection, it actually seems rather prescient in today’s volatile climate: world economies collapsing, old alliances breaking, friends becoming enemies, suspicion growing about immigrants and foreigners, fear and paranoia running rampant in the land.

It’s also been said that it’s too slim, too quick a read, and for that reason a bit lightweight in sci-fi terms. Personally, I couldn’t disagree more. If a book does its job in 100 pages rather than 1,000, it’s still done its job. And at least you can’t complain that it’s been padded.

As always – just for fun – here are my selections for who should play the leads if The Black Corridor ever makes it to the movie or TV screen (and what a fascinating challenge for any screenwriter that would be), but as there’s only one real star of this story, I’m only bothering to cast one person, and for that I’m opting for my main man of the moment.

Ryan – Tom Hardy

Published on June 27, 2017 01:55

June 16, 2017

When our favourite heroes face true peril

It’s a big news week this week, at least for those interested in the respective futures of Detective Sergeant Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg and Detective Constable Lucy Clayburn.

It’s a big news week this week, at least for those interested in the respective futures of Detective Sergeant Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg and Detective Constable Lucy Clayburn. Before we get to that, and on the subject of cops under pressure in a very dark world, I’m also proud today to be reviewing and discussing David Jackson’s superbly entertaining, New York-based crime thriller, PARIAH. If that feature is the main reason you’re here, you’ll find it, as usual, at the lower end of today’s column – feel free to scroll your way down there now.

However, if you’ve got a bit more time and are fans of the Heckenburg and Clayburn books, you might be a bit interested in the following …

The weeks leading up to Christmas are usually pretty exciting, but as we raced towards the end of 2016, I was a bit more excited (and tense) than usual. In early November last year, I entered discussions with my publishers, Avon Books at HarperCollins, to maybe continue the two crime sagas I’ve recently been writing: the DS Heckenburg novels, and what, as most punters will have now guessed, was always intended to be a parallel crime series, the Lucy Clayburn books.

It may be a surprise to some that I had to discuss it at all. After all,

STRANGERS

, the first of the Clayburn novels, became a Sunday Times best-seller within a month of publication, while the Heck novels, particularly the most recent one,

ASHES TO ASHES

, have pulled in some astonishingly good reviews.

It may be a surprise to some that I had to discuss it at all. After all,

STRANGERS

, the first of the Clayburn novels, became a Sunday Times best-seller within a month of publication, while the Heck novels, particularly the most recent one,

ASHES TO ASHES

, have pulled in some astonishingly good reviews.But we authors don’t glue ourselves permanently to any particular character or series of characters, no matter how popular they may become. At least, we don’t plan to. Okay, I can’t speak for everyone in this … but I think it’s fair to say that we all of us have ambitions to broaden our writerly horizons. We don’t want to write about the same people all the time.

Hence the long chat I had with Avon.

It’s always a strange time for an author, that. Because even if you’ve enjoyed a happy and fruitful relationship with a publisher – as I definitely had with Avon, particularly with regard to the Heck and Clayburn books – you can’t help but question whether the grass might be greener elsewhere. You swap notes with fellow writers, you start mulling over different ideas, possible new directions, you discuss it with your agent, your wife, husband etc.

But ultimately, you wonder ...

You wonder if you’ve been in your comfort zone for too long, and if maybe your work has stagnated as a result.

You wonder if opting to write something completely different might totally re-energise you.

However … if you guys are all reading this now and assuming I’m about to declare that I’m either leaving Avon Books and/or dumping my two cop heroes, you’d be wrong. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

However … if you guys are all reading this now and assuming I’m about to declare that I’m either leaving Avon Books and/or dumping my two cop heroes, you’d be wrong. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.I’m very happy to announce that, after all the soul-searching I mentioned above, I’ve signed a new deal with Avon, and that both Heck and Lucy Clayburn will continue to work their cases harder than almost anyone else into the foreseeable future under the HarperCollins banner.

As such, another Lucy book – SHADOWS – will follow this year (in October, to be precise), the next Heck novel, as yet untitled, will hit the shelves sometime around next spring, and Lucy, most likely, will appear again later on in 2018.

You may wonder, ‘okay, so … why give us all that gabble beforehand?’

The simple answer is that lots of people have recently been asking what my plans are for the two characters, and have expressed concern that I seemed cagey or even unsure about what was going to happen next. The truth is that I wasn’t really able to say anything because I was genuinely undecided – it was, as I think I’ve underlined, a difficult decision.

But at the end of the day, I suspect I was always destined to sign on at Avon again. Firstly, they’ve done a great job with the novels so far, and have encouraged, supported and assisted me in every conceivable way as I’ve developed my two main characters. I’ve long felt I had something valuable in my connection to Avon – a relationship that more resembles close friendship than employer and employee hooked-up for mutual convenience, and this is something which, from my many chats with fellow authors, is not by any means a given when you move on to pastures new. If I’d decided to head elsewhere, I’d have been risking losing something very precious.

In addition, of course, I still have a directory’s worth of untapped ideas for both Heck and Lucy, and, quite frankly, it would have been an out-and-out crime to leave it there. Not only that, I’ve realised these last few months how emotionally attached I’ve become to these two fictional personalities – every day, it seems, I’m thinking up possible new developments in their careers. Merely considering drawing a sudden line under them actually affected me with a sense of physical loss.

So there we are: I’m still with Avon Books, at least for another couple of books, and, as I said before, both Mark Heckenburg and Lucy Clayburn will continue to hunt the bad guys with every ounce of strength in my body.

And now for something completely (well, a little bit) different …

Last year, I wrote a special blogpost for BLOOMIN BRILLIANT BOOKS on the subject of my research techniques, and what lengths I must go to in order to create the authentic feel of the homicide detective’s world. That was half a year ago now, of course, last October in fact, and so, with many thanks to BLOOMIN BRILLIANT BOOKS – and hopefully for your interest – I’m able to reproduce it in full here, today …

How do you research for your cop fiction?

I suppose it all boils down to how much research you actually want to do.

Do you want to be as precise as possible and follow real police procedure to the absolute letter of the law? Or are you quite happy to cut corners in order to tell a rattling good story?

Either way, I have a slight advantage because I was once a serving police officer, albeit some time ago now. Given that police protocols change so regularly, and vary so much from force to force, my basic knowledge is hardly likely to be 100% accurate. That said, my service did ensure that I have a good basic understanding of police life, police attitudes, police relationships, and I like to think that I’m fairly well informed when it comes to the law, though I too have to update my legal knowledge on a regular basis.

Either way, I have a slight advantage because I was once a serving police officer, albeit some time ago now. Given that police protocols change so regularly, and vary so much from force to force, my basic knowledge is hardly likely to be 100% accurate. That said, my service did ensure that I have a good basic understanding of police life, police attitudes, police relationships, and I like to think that I’m fairly well informed when it comes to the law, though I too have to update my legal knowledge on a regular basis.Thankfully, I still have some of my old crime investigation manuals to hand – very grubby and dog-eared though they are – and there are still lots of police buddies I can consult when it comes to tricky issues. In addition these days, we all have an amazing resource of information in the internet. Complex, detailed data that once could only be discovered by going to the library or visiting the local Citizen’s Advice office is now available at the push of a button. Law exists online, the rights of citizens are available online, police procedures at the time of arrest and custody are online – it’s not difficult to keep yourself appraised of essential developments.

Which brings me back to the point I raised earlier. How much hard fact to you want to include?

Some authors are very hot on procedure, while for others it’s nothing more than a vague background. I guess I fall somewhere between the two. I like things to be as accurate as possible, but by the same token I consider that I’m writing thriller fiction not police textbooks. So I don’t like to overdo it. But that doesn’t mean I don’t keep my ear to the ground and read up on new cases and systems, which can be a time-consuming process.

Of course, one key advantage the average crime writer has in this regard is the sheer amount of misinformation already out there. Most members of the public have never visited a real-life murder scene, and hopefully never will. Nevertheless, they think they know what goes on because they’ve seen it so often in the movies and on television. But most dramas operate on the same principles that we novelists do: in other words, their priority is not always to be absolutely faithful to real life, and they too will skimp on inconvenient details. In addition to this, there are some investigative techniques that official police advisers will not speak to writers, publishers or film and TV producers about, and I won’t even name them here. It definitely suits the police if not all the tricks of their trade are known to the public; there are some areas where they are more than happy for crime authors like myself to make stuff up.

With my last Lucy Clayburn novel, STRANGERS , there is no way that even as a former copper, I could just have grabbed up my keyboard and started bashing it in.

To start with, STRANGERS is about a policewoman, not a policeman. Not only that, it’s a policewoman who needs to go undercover among Manchester’s prostitutes to try and snare a vicious female serial killer called Jill the Ripper, a streetwalker who is murdering and mutilating her male clients.

How could I know what it would be like as a young woman, who as part of her duty must don the most suggestive clothing and walk the roughest parts of town at the dead of night, while actively seeking the company of deranged offenders?

How could I know what it would be like as a young woman, who as part of her duty must don the most suggestive clothing and walk the roughest parts of town at the dead of night, while actively seeking the company of deranged offenders?But thankfully, I had this covered too. The author Ash Cameron, a personal friend of mine, is also a former police officer, and she performed this perilous duty many, many times during her own days in the job. So, I had more than a few discussions with her on the subject, and trust me, I got it chapter and verse, and you will too if you fancy checking out STRANGERS , in which I skimp on no lurid detail.

Even so, I reiterate that I’m not in the business of writing how-to manuals. On occasion, the mythology of police work is much more entertaining than the reality – how much do you really want to know about mountains of soul-sapping paperwork, or sitting in court for hours while lawyers argue over minutiae?

That doesn’t mean to say that the truth can’t every bit as compelling and hair-raising as the fiction. But for me it's about finding a happy medium midway between the two. I guess it’s over to my readers now to see what they make of it.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS ...

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

PARIAH

by David Jackson (2014)

PARIAH

by David Jackson (2014)

Detective Callum Doyle is one of New York’s finest. But he’s not the most popular guy in the station-house. Wrongly accused of once having an affair with a colleague’s wife, who subsequently died in a shoot-out with a worthless hoodlum, there is a distinct lack of support from his work-mates when a faceless and relentless killer targets him for isolation, eliminating anyone he gets close to in the most cruel and horrific ways.

The book starts at a hundred miles an hour with the slaying of two of Doyle’s fellow-cops, Detectives Parlatti and Alvarez, both of whom at the time of their deaths happen to be partnered with him. Letters are then sent threatening the lives of anyone Doyle has contact with – police personnel, family, friends and even those criminals he happens to be investigating.

Initially, the rest of the Detective Squad reacts the way you’d expect, showing determination to crack the case and bring the mysterious madman to justice. However, it soon becomes apparent that this calculating individual enjoys several big advantages over the NYPD and over Callum Doyle in particular.

To start with, he remains bewilderingly anonymous, carrying out his hits with ultra-professionalism, leaving not a clue for his pursuers to work with. He also – and this is the real butt-kicker for Doyle – seems constantly to be two or three steps ahead. It’s inexplicable, but the guy always appears to know exactly where Doyle is and who he’s interacting with, and as promised, he duly obliterates these unfortunates with extreme and elaborate viciousness.

Even Doyle’s most nefarious contacts, regular Internal Affairs opponent Paulsen, and washed-up former boxing pal-turned-informer, Mickey ‘Spinner’ Spinoza, find themselves in dire peril.

No-one, it seems – literally no-one – is safe.

Doyle is certain the answer lies in his own past. It’s just a matter of going through the files and trying to identify if there’s anyone who bears him this much ill will and who is capable of mounting such a campaign of terror. But increasingly, Doyle’s colleagues – especially those who were iffy about him from the start – are hesitant to assist. They’ve got lives to lead too, not to mention families whose welfare they fear for. In truth, Doyle has only one true friend in the department, Lieutenant Mo Franklin, heir to a wealthy estate and husband to the sexy Nadine, who has become a close pal of Doyle’s homely wife, Rachel – but now even Franklin has become concerned that his top detective is a danger to everyone, and so advises him to take an indefinite period of leave.

Doyle keeps working the case – of course he does; he’s no intention of playing this crazy game. But things get much tougher when the lunatic switches his attention to Doyle’s family (and in one instance in the most harrowing and heart-rending way).

In some ways, Doyle thinks it might be better if this nameless enemy was simply planning to kill him. Because what happens now is infinitely worse: a living death, permanent and complete separation from his fellow men. Doyle literally must bury himself in a roach-motel and sever all contact with the outside world. And how can he fight back in such a predicament? Even the underworld, having lost some of their own to the killer, hold him at arm’s length – with the exception of low-level Mafia hood, Sonny Rocca, who Doyle has had run-ins with before but whom he basically likes, and far more scarily, the Bartok brothers, two major players on the New York crime scene.

For reasons of their own, Rocca and the Bartoks are ready to help Doyle, though of course this kind of help only comes at the sort of price a good cop will struggle to pay. Just when he thought things couldn’t get any worse, Doyle now has this nightmare decision to make: does he give up his life as he knew it previously, or does he give up his soul? …

First and foremost, the most impressive thing about Pariah – at least as far as I’m concerned – is the authenticity with which it is written, especially given that David Jackson is a British writer. It completely captures the world of a busy New York City police precinct, with believable dialogue, convincing use of genuine procedures (some serious research on show there, Mr. Jackson!), non-intrusive but atmospheric use of real locations, and lots of the kind of rugged, hard-bitten grotesques you’d expect to meet on the mean streets of the Big Apple.

It’s to the author’s credit that so few likeable characters populate these pages: pimps, addicts, winos, bang-bangers. Not every punter has reviewed this aspect of the book favourably, arguing that it perhaps wallows a little too much in grimness, and that maybe a few nicer personalities would be refreshing. But it works excellently for me and shows that Jackson is determined to immerse us in a version of NYPD life which is as close as damn it to the real thing.

This brings me fully onto the issue of David Jackson’s characterisation, which in Pariah is razor-sharp from the outset, but also pretty merciless.

Far from the oft-depicted police world of white knights and unbreakable brotherhoods, it feels here as if Callum Doyle’s work-buddies let him down disappointingly quickly. Again, this is an effort by Jackson to reflect real life. Let’s face it, Doyle was a guy with baggage and not too many friends to start with, and this confirmed outsider status was never likely to endear him to his fellow cops when it started to look as if he’d suddenly become a walking bullet-magnet.

Doyle, for whom Pariah is the first of several no-holds-barred outings, makes for a traditional flawed hero, his background in boxing giving him ‘man’s man’ kudos, but the suspicion with which he’s held in by certain colleagues even before he’s become the object of the killer’s hatred understandably steers him towards the friendship of lowlife informers like Spinner, Sonny Rocca and even Mr. Unpopular himself, IA investigator Paulsen. Doyle’s a family man, of course, so his home life is comfortable, almost cosy, but then there is still that lingering doubt in the minds of so many who know him about whether he had an affair or not, and the mere presence of loved ones presents its own kinds of difficulties, especially with a ruthless psycho hanging around. So, it’s never cakes and ale for Callum Doyle, not even on the domestic front.

The rest of the cops are convincingly drawn; even good guys like Parlatti and Alvarez have issues, while one particular member of the Detective Squad, Schneider, is an out-and-out hate mobile, one of those archetypical fat-necked, loudmouthed, aggressively opinionated law enforcement bullies of the old school and very much the opposite number to Doyle’s fearless pursuer of genuine justice.

I was somewhat less sold on Mo Franklin. Not because he didn’t strike me as the real deal – in the workplace he certainly did, but his home life is perhaps a little too gold-plated. I had trouble buying into the huge inheritance, the big house and the kittenish wife. But that’s probably the only brickbat I’ve got for Pariah , and it certainly didn’t spoil my enjoyment of it.

This is a taut, fast-moving detective thriller, based on a singular and intriguing concept. When a cop is completely ostracised – when he literally has no access to any of his normal support networks, neither cop buddies, non-cop buddies, friends, loved ones, and certainly none of those basic departmental essentials like Forensics, Ballistics etc – how can he even start to track down so sadistic and yet sophisticated a maniac?

This is a truly great idea, very well executed, which screams to be adapted for film or TV. It also features some truly hair-raising moments – check out the scene in the nightclub alley! – which lift it well above the average police procedural, certainly in the action stakes, though it has its cerebral moments too; when Doyle is too weary and battered to keep on hitting the streets, he must fall back on that often most underused tool in detective fiction, his brain – though to talk much more about that would be a spoiler for sure.

Suffice to say that Pariah has my strongest recommendation. It’s a high-octane page-flipper, filled with unforeseen twists, which I defy anyone to get through in more than two or three sittings.

As always, at the end of these book reviews, I’m now going to be cheeky enough to indulge in some fantasy casting and list those actors I personally would pick were this novel ever to make it to the screen. Here, purely for fun you understand, are my selections for who should play the lead characters in Pariah:

Callum Doyle – Jude LawRachel Doyle – Jennifer EspositoMickey ‘Spinner’ Spinoza – Micky RourkeSonny Rocca – Michael ImperioliPaulsen – Robin Lord TaylorMo Franklin – John TurturroNadine Franklin – Sarah Michelle Gellar

(I know, this cast wouldn’t come cheap, but there’s never any point doing this if I haven’t got limitless funds to work with!!!).

Published on June 16, 2017 06:28

June 1, 2017

Villains beware ... these hunters never tire!

Today, we’re talking cop heroes who come back again and again … whether that be in book form, on TV, the cinema, or preferably all three!

Today, we’re talking cop heroes who come back again and again … whether that be in book form, on TV, the cinema, or preferably all three!We’re doing that first of all because I intend to wax lyrical about the TOP TEN TV COP SHOWS THAT HAVE MOST INFLUENCED MY CRIME WRITING, but also because I intend to review and discuss Michael Stanley’s fantastic Botswana-set cop thriller, DEADLY HARVEST, part of a crime investigation series which, more than almost any other I’ve encountered, illustrates the vast range of styles, tones and subject-matter available within the confines of this very special genre.

If you want to know more about that, though, you’ll have to head down towards the bottom of today’s post, where I review the book and discuss it in some detail. Before then, here as promised is a bit of lyrical waxing …

There are plenty of crime novelists whose heroes return for more. I think that all we crime authors enjoy that aspect of our job, particularly those of us who write from the POV of an investigator. It’s a genuine thrill to have created a hero or heroine who so connects with your readership that the clamour to see more of them rises and rises until it cannot be ignored … especially when the net-result is that you finish up with your own cop thriller franchise.

This isn’t just a big thumbs-up for the work you’ve done, and hugely gratifying for that reason alone, it also opens the whole thing up into a more exciting field, allowing you to develop your central character on an episodic basis, throwing more and more challenges at him/her, confronting them with an ever wider variety and multiplicity of threats, and learning more about them, yourself, as you progress.

Strangely, though … whereas for the writers this is usually the desired outcome (often an ambition rather than a certainty), readers appear to regard it as the norm. They almost expect it to happen, and my suspicion is that this boils down to the way we’ve been conditioned over the decades by a never-ending supply of cop shows on the goggle-box. They’ve been with us almost since the beginning of TV, and from the outset have adopted this very same format, hitting us week after week with a succession of free-standing dramas connected by over-arching story arcs and returning characters, who inevitably grow in strength and stature and profile until they are virtually immortal.

And immortality is undoubtedly the status we’d all like our cop characters to achieve, even if we don’t exactly anticipate it. For which reason, I’m very proud that on April 6 this year,

ASHES TO ASHES

, the sixth novel in my DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg series, was published. Heck works for Scotland Yard’s Serial Crimes Unit, which, as part of the National Crime Group, sends him all over England and Wales. But he’s a cop whose personal life is massively complicated by the fact that his ex-girlfriend is now his boss, by hideous events in his early years, and by an innate obsessiveness, which sees him embark on such dogged pursuits of justice that he will literally stop at nothing to get a result.

And immortality is undoubtedly the status we’d all like our cop characters to achieve, even if we don’t exactly anticipate it. For which reason, I’m very proud that on April 6 this year,

ASHES TO ASHES

, the sixth novel in my DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg series, was published. Heck works for Scotland Yard’s Serial Crimes Unit, which, as part of the National Crime Group, sends him all over England and Wales. But he’s a cop whose personal life is massively complicated by the fact that his ex-girlfriend is now his boss, by hideous events in his early years, and by an innate obsessiveness, which sees him embark on such dogged pursuits of justice that he will literally stop at nothing to get a result.I’m totally delighted that Heck has now commanded sufficient attention in the crime market to have lasted this long in print. Hopefully, there are more books to come – I certainly have plenty more planned.

Anyway, referring back to that huge influence I mentioned previously, as exerted by all that classy cop TV we’ve been so prolongedly exposed to, here, in no particular order, are ...

THE TOP TEN COP SHOWS THAT HAVE INSPIRED MY WORK THE MOST

(I’d love to, and could easily have, chosen many more, but we have to draw the line somewhere, alas):

The Sweeney (75-78): British TV put the stern but friendly beat-bobbies of the Dixon of Dock Green era firmly behind it with this high-energy action series from Thames Television, which focussed on the investigations of the Flying Squad, London’s elite anti-robbery unit. It shocked even 1970s audiences with its sex and violence, and made lasting stars of John Thaw and Dennis Waterman. Teak-tough coppering of the genuine old school.

The Sweeney (75-78): British TV put the stern but friendly beat-bobbies of the Dixon of Dock Green era firmly behind it with this high-energy action series from Thames Television, which focussed on the investigations of the Flying Squad, London’s elite anti-robbery unit. It shocked even 1970s audiences with its sex and violence, and made lasting stars of John Thaw and Dennis Waterman. Teak-tough coppering of the genuine old school.Dragnet (1949-2003): Dragnet may sound as if it’s the longest-running police show in history, but it’s had various incarnations: on the radio, on TV, and on the big screen, but the cases of LA detective Joe Friday, the arch wheeler-dealer in the midst of urban mayhem, are never less than enthralling. Several TV stars have played him, including Jack Webb and Ed O’Neill. Stands alongside The Untouchables as one of the granddaddies of TV cop dramas.

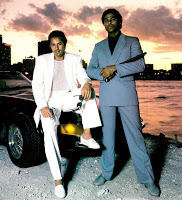

Miami Vice (1984-89): Allegedly sold on a two-word pitch – MTV Cops – this extraordinary fashion parade of a crime series rewrote the rules in the mid-80s, putting on a show that was faster, slicker and more explosive than anything prior to it, pitting snazzily-dressed Miami detectives Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas against a succession of drugs-dealing sleazeballs. Often OTT, it spellbound its initial audiences with its gaudy displays of carnage.

Miami Vice (1984-89): Allegedly sold on a two-word pitch – MTV Cops – this extraordinary fashion parade of a crime series rewrote the rules in the mid-80s, putting on a show that was faster, slicker and more explosive than anything prior to it, pitting snazzily-dressed Miami detectives Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas against a succession of drugs-dealing sleazeballs. Often OTT, it spellbound its initial audiences with its gaudy displays of carnage.The Wire (2002-08): Seen by many as one of the greatest crime series of all time, The Wire broke all regular cop show protocols by telling its stories from the perspectives of the criminals as well as the police (usually non-judgementally), and in so doing, painted a vivid, warts-and-all picture of its host city, Baltimore. Sharply observant and meticulously written, it still dominates as one of the classiest and most literary police procedurals in TV history.

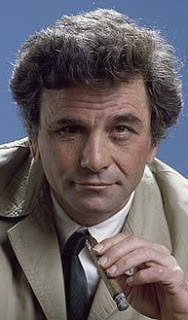

Columbo (1968-90): Peter Falk was already a household name when he took this role (which Bing Crosby rejected!), but it would still send his career stratospheric. His pitch-perfect portrayal of the scruffy but shrewd Lieutenant Joe Columbo perfectly complemented the show’s unique formula, in which we all knew who the murderer was but the tension stemmed from the cat-and-mouse game played between Joe C and his (often) star-name adversary.

Columbo (1968-90): Peter Falk was already a household name when he took this role (which Bing Crosby rejected!), but it would still send his career stratospheric. His pitch-perfect portrayal of the scruffy but shrewd Lieutenant Joe Columbo perfectly complemented the show’s unique formula, in which we all knew who the murderer was but the tension stemmed from the cat-and-mouse game played between Joe C and his (often) star-name adversary.Hill Street Blues (1981-87): In some ways a soap opera, but nevertheless a firm favourite with crime fans, Hill Street unashamedly took us into the private lives and loves of a whole range of individuals working a big inner-city police precinct. Action interwove with social drama as an ensemble cast of compelling characters worked their way through difficult shifts, which they often struggled to recover from afterwards. Gritty and unmissable cop TV.

The Shield (2002-08): Fox TV’s finest hour, as Detective Vic Mackey led his cold-blooded Strike Team in a non-stop war against the street-gangs of south-central LA, doing everything possible to pin the hoodlums down but at the same time getting rich from the illegal proceeds. Criticised for its ‘understanding’ portrayal of corrupt police officers, this eye-poppingly well-made cop show remains one of the most emotionally intense ever to hit the screen.

The Shield (2002-08): Fox TV’s finest hour, as Detective Vic Mackey led his cold-blooded Strike Team in a non-stop war against the street-gangs of south-central LA, doing everything possible to pin the hoodlums down but at the same time getting rich from the illegal proceeds. Criticised for its ‘understanding’ portrayal of corrupt police officers, this eye-poppingly well-made cop show remains one of the most emotionally intense ever to hit the screen.Cagney and Lacey (1982-88): Picking up the gauntlet where Angie Dickinson’s pioneering Police Woman dropped it, Cagney and Lacey followed the buddy-buddy cop format, but in this case with two female detectives, Tyne Daley and Sharon Gless, trawling New York’s mean streets, leading very different private lives, encountering endless chauvinism, and yet proving as effective a crime-fighting duo as any of their male counterparts. Great banter too.

Messiah (2001-2008): Though there have only been four installments in this hard-hitting BBC adaptation of (and spin-off from) Boris Starling’s original novel, Ken Stott has never been better as DCI Red Metcalfe, whose adversarial Murder Squad pursued vicious killers responsible for crimes crazier and more harrowing than we’d ever seen before. The first outing in particular – which included crucifixions and sawings-in-half – struck new levels of horror in TV police drama.

Messiah (2001-2008): Though there have only been four installments in this hard-hitting BBC adaptation of (and spin-off from) Boris Starling’s original novel, Ken Stott has never been better as DCI Red Metcalfe, whose adversarial Murder Squad pursued vicious killers responsible for crimes crazier and more harrowing than we’d ever seen before. The first outing in particular – which included crucifixions and sawings-in-half – struck new levels of horror in TV police drama.Happy Valley (2014-16): One-time soap star Sarah Lancashire won deserved praise for her performance as a droll uniformed sergeant in a none-too-idyllic English rural setting, where she was confronted by drugs, rape, kidnapping and serial murder. A humungous hit on British television, Happy Valley made audiences nervous with its graphic portrayal of violent crime and its repercussions, and for its frank depiction of a tired police force in a very bleak world.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

DEADLY HARVEST

DEADLY HARVEST by Michael Stanley (2016)