Paul Finch's Blog, page 10

July 14, 2019

Festival time again: plenty of fun to be had

It’s that time of year again: the lovely month of July, which means that the Theakston’s Crime Writing Festival at Harrogate, the biggest annual event in so many of our professional lives, is just around the corner.

As always, I’m very honoured to be participating in this, especially as, being a new boy in the Orion stable, I’ve actually got a role to play this year in the legendary Orion Incident Room.

For those interested, however, Harrogate isn’t the only place where I’ll be mingling with friends, colleagues and the public in general before the end of this month. I’ll also be making a guest appearance in a ‘Meet the Writer’ event at the Brasshouse pub in Birmingham.

More about both of these events in a little while. In addition today, I’ll also be looking at I AM DEATH, the heavyweight crime thriller from Chris Carter, reviewing and discussing it in my usual forensic detail. If you’re only really interested in the Carter review, that’s no problem. Zoom straight on down to the bottom of today’s blogpost, which is the usual place to find my book chats.

However, if you’re interested in hearing about the other stuff first, then here we go …

Getting out there

First off, Harrogate ...

2019 sees the 16th Theakston’s Crime Writing Festival, which is to be held (as usual) at the Old Swan Hotel, Harrogate, from 18-21 July, in other words this coming weekend.

It’s always a major event in the crime and thriller writing world, not least because of the amazing line-up of special guests who grace it each year. This time, for example, attendees will be rubbing shoulders with the likes of Harlan Coben, Ian Rankin, Belinda Bauer, Eva Dolan, Jo Nesbo, Val McDermid, Stuart Macbride, Jeffery Deaver, James Patterson and Jed Mercurio (among many others).

I’ll be going, as always, but this year, as I say, I’ll have a role to play in the Orion Incident Room, which will be located in the Swan Hotel’s Library Room. There are all kinds of events taking place there during Friday July 19, but for my own part it’s a case of ‘Justice a Minute’, a panel quiz show and our own special Harrogate version of Just a Minute, as hosted by Steve Cavanagh, Luca Veste and Craig Sisterton, starring (as well as me) such crime author luminaries as Adrian McKinty, Mason Cross, Stephanie Marland, Marnie Riches, Johnny Shaw, Mark Billingham and Val McDermid.

Be there or be fair game for all of us. It kicks off at 9.30am.

If this isn’t enough of a draw for you, the Theakston Crime Festival offers lots of other intriguing bits and bobs, including panels, chats, interviews, book signings and the like. And as I say, there’ll be the usual august company of excellent crime and thriller authors strolling the hotel grounds just waiting for you to doorstop them …

Now, The Brasshouse ...

This is a really delightful thing that has come completely out of the blue. In short, I’ve been invited as a guest to attend a very famous hostelry, The Brasshouse pub on Broad Street in Birmingham city centre, mid-afternoonish on Sunday July 28, at a special ‘Meet the Author’ event, which this year is part of the Birmingham Jazz Festival (now in its 35th year).

This is a really delightful thing that has come completely out of the blue. In short, I’ve been invited as a guest to attend a very famous hostelry, The Brasshouse pub on Broad Street in Birmingham city centre, mid-afternoonish on Sunday July 28, at a special ‘Meet the Author’ event, which this year is part of the Birmingham Jazz Festival (now in its 35th year).Now, you may wonder what I know about jazz, and let me tell you, it’s little-to-nothing. However, fortunately I won’t be having much to do with the musical aspects of the event (which is a good thing as I can neither sing nor play a single instrument). This ‘Meet the Author’ is a little extra thing, I’ve now learned, which seems to have been arranged specifically for me. The invitation came about because the pub’s proprietors were delighted to see the following small passage appear early on in SHADOWS , my second Lucy Clayburn novel:

Tonight, oddly, even though the rest of his mates were well-known on campus as big-time boozers, Keith Redmond had somehow found his way to the last port of call alone.

Tonight, oddly, even though the rest of his mates were well-known on campus as big-time boozers, Keith Redmond had somehow found his way to the last port of call alone.

It was called The Brasshouse and it was located on Broad Street, where its reputation as a popular watering hole was very well deserved.

To fill you in, something very nasty happens to Keith Redmond about eight pages after this, but if you want to find out exactly what, you’ll need to buy the book. Suffice to say that it sets in motion a procession of violent and terrifying events.

Thankfully, The Brasshouse itself doesn’t get embroiled in any unpleasantness; it just happens to be the last pub to host Keith, who arrives there at the end of a night out with his rugby mates, before setting off home … and meeting his ghastly fate en route.

Anyway, I’ll be reading a bit from the book and answering some questions (and signing some books if anyone wants me to), at The Brasshouse on July 28. Again, I’m very honoured to have been asked to do this. It was an unexpected and unusual invitation, but hugely flattering, and I can’t wait to take part.

Hopefully, I’ll see some of you there …

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

I AM DEATH

I AM DEATH by Chris Carter (2015)

Detectives Robert Hunter and Carlos Garcia are close compadres in the LAPD’s Robbery Homicide Division, specifically the Homicide Special Section, which handles ultra-violent or particularly sadistic murder cases.

In a nutshell, these two have been seeing and dealing for years with the very worst of the worst, so they are well-used to it. Almost nothing has been able to shock them … until now, when a killer, who simply calls himself ‘Death’ begins abducting young women and subjecting them to the most unimaginable suffering before discarding their ravaged corpses. He also writes fiendishly gleeful letters, not just to the cops but to the Mayor’s Office, which inevitably means that this case gets the highest priority possible, and allegedly, or so he says, peppers them with cryptic clues, which the detectives struggle to decipher.

In many ways, it’s the archetypical serial killer scenario, and it comes at us in the way these sorts of tragedies often play out in real life, the killer growing steadily bolder and more brutal and the cops knowing they’ll have to catch the madman quickly, otherwise their department will be embarrassed to the nth degree, a mass panic will manifest, local politicians will run amok, and senior officers take early retirement just to get out of the unflattering limelight.

However, there are certain slight differences here from the blood-soaked norm … just to make things even more difficult for Hunter and Garcia than they already are.

The killer’s MO changes regularly, so no recognisable pattern develops, and he even pays a call on Hunter one very dark night, just to show the detectives that they themselves could be in the firing line if their opponent decides there’s a need for it.

However, Hunter and Garcia are experts in this field and have bags of experience between them. With time-honoured detection methods, they quickly close their target down. Encouraged by the sympathetic and helpful Captain Blake, and when help arrives from Detective Troy Saunders of the Missing Persons Bureau, they finally settle on a viable suspect. Naturally, the guy in the frame has gone to ground beforehand, but they know who he is and it’s only a matter now of locating him and plucking him off the streets, and with every man and woman in the job looking for him, that surely won’t take long.

Except that Hunter starts to wonder if it’s all been a little too easy.

Death is a clever opponent. Would he really let them get this close so soon? There has to be something else, some unseen factor. And if Hunter and Garcia miss it, it’s anyone’s guess what unspeakable acts of horror will follow …

With the exception of one parallel strand, in which we follow the misfortunes of a young loser called Ricky Temple, who is kidnapped on his way home from school, and horribly maltreated by his abductor (who may or may not be Death), who renames him ‘Squirm’ and locks him in a filthy cellar, I Am Death actually reads like the fictionalisation of a real-life murder investigation. Though he spares us any ‘by the numbers’ procedural detail, Chris Carter hits us with what feels like a very real serial killer situation, a typically amoral and narcissistic unsub embarking on a reign of terror by abducting, torturing and slaughtering random young women and then writing gloatingly to the authorities, evidently delighting in the sense of empowerment this gives him.

Yes, all the predatory lunatic boxes are ticked so far.

The same applies to the cops, the obsessive Hunter and the likeable Garcia going about their enquiry in intelligent, workmanlike fashion, uncovering clues, chasing down leads and refusing to be affected by the sensational aspects of the case: there are no over-the-top car chases here, no epic gun battles, and dare I say it – and this hasn’t won the approval of all reviewers, as you can imagine – no female characters shoehorned in as a sop to political correctness. Most of the homicide detectives, with the exception of Captain Blake, are male, while the majority of the women who appear anywhere in the book are victims.

As I say, not every reader has been happy about this, but if you want realism, that’s probably still the way of it in many cases of sexual homicide in the City of Angels.

However, there is one very BIG difference between this book and factual narratives relating real-life murder investigations. And that is the horrific level of violence.

Okay, there’s no doubt that in the real world, some killers will savage their unfortunate victims in similarly ghastly ways to these, but if so, you’re unlikely ever to read the full gory detail when it hits the newspapers. In truth, I’ve never encountered anything quite like I Am Death wherein the torturous deaths of the victims are so intensely and protractedly described. And trust me, they really are harrowing; one poor soul has her face sanded off while she’s still alive (just take a second to think about that!), and the readers are barely spared a moment of it.

That’s not the only sadistic outrage that Carter’s deranged villain perpetrates here. Nearly all the crimes are sickeningly horrible. If you’re able to stomach all that, I Am Death is a very good read, but the violence it’s totally out there … way beyond what you’d expect to find in your average cop novel, and even beyond your average horror novel if I’m honest.

Of course, ultimately this kind of thing is subjective. If you really, really don’t like it, there’s nothing to stop you putting the book down, but someone somewhere in the editorial hierarchy of Chris Carter’s publishers decided that it was essential to the plot, and who am I to argue with that? Carter is known as a US crime author who pulls no punches.

It could be that if you’re really offended by this stuff, you won’t be reading about Robert Hunter in this, his seventh outing, anyway, and so this warning is redundant. On the other hand, if you genuinely don’t mind it – and there are plenty of hardcases out there in Reader Land – you’ll probably find I Am Death a very entertaining police thriller. Though we follow what at times feels almost like a routine investigation from the cops’ POV, it won’t surprise you to learn that it isn’t quite as straightforward as it may appear. Simple answers in a book like this are always going to be deceptive. And if you don’t expect a killer twist at the end – and this novel has one of the biggest of all – you’re possibly reading in the wrong genre.

In short, I Am Death is another big-hitter among adult crime thrillers. A tense and compelling murder enquiry pitting a truly hateful antagonist against two pleasing, everyman heroes, but with mercifully few buddy-buddyisms and zero office politics. Again though, just be warned – when the blood flows in this one, it’s in rivers rather than buckets.

I’m now going to do my usual fantasy casting thing, picking the actors I’d like to see take the lead roles should I Am Death ever hit our screens. Whether the Robert Hunter investigations have ever been considered for TV, I don’t know, but if it does happen, the producers will obviously have to start at the beginning rather than simply charge in at the seventh novel (like I’m doing), so in that regard you’ll have to suspend your disbelief even more than you normally would at this part of the blog.

Detective Robert Hunter – Chris PrattDetective Carlos Garcia – Wagner MouraCaptain Blake – Michelle HurstDetective Troy Saunders – Daniel Day-Lewis (I’m sure we could tempt him out of retirement for one final juicy role)

Published on July 14, 2019 14:17

July 9, 2019

Price slice! Bargain deals on killer thrillers

A ‘get em cheap while you can’ blog this week. Basically, I’m just letting everyone know about some pretty good deals currently available online if you’re interested in acquiring any crime titles from my back-catalogue.

For those not in the know, they are old-school Brit Grit; cops hunting killers in the grimmest of circumstances in all corners of the modern-day UK.

At the same time, while we’re on the subject of Brit Grit, I’ll be reviewing and discussing MW Craven’s amazing novel, THE PUPPET SHOW, which is as British and as gritty as they come. If you’re only here for the Mike Craven review, that’s fine; you’ll find it, as always, at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Feel no shame in speeding on down there straight away.

However, if you’re interested in the other stuff too, then stick around for a few minutes and I’ll fill you in on the details.

Bargains … bargains … bargains …

Both my current cop series, the Mark Heckenburg novels and the Lucy Clayburn novels, are currently benefitting from some competitive pricing on Amazon; at least, the ebooks are.

So, if you want to know what all the fuss is about, and you enjoy reading ebooks, now might be the time to take a chance on them. But a quick round-up first.

MARK HECKENBURG

My Mark Heckenburg books follow the investigations of a detective sergeant in the National Crime Group’s elite Serial Crimes Unit. Heck is specialist homicide investigator with a dogged attitude to work, but he is beset by continuing personal problems. He lives virtually in exile from his family due to his having joined the police shortly after his older brother, Tom, was framed by bent coppers for a series of crimes that he didn’t commit (as a result of which, Tom took his own life while he was in prison). Heck also has a ‘fire and water’ relationship with his departmental boss, Detective Superintendent Gemma Piper, firstly because they don’t see eye-to-eye on procedural matters, but mainly because, earlier in their careers, they were boyfriend and girlfriend. They’ve never shaken off the affection they hold for each other or the sexual chemistry between them, and in the kind of hardcore, front-line police investigations that SCU get involved with, that isn’t a good thing. You can presumably imagine the emotional chaos that result.

I’ll list the books now, in chronological order. As I say, the prices are all very reasonable at present, quite a few of them available in ebook form for only 99p.

STALKERS

(ebook 99p)

STALKERS

(ebook 99p) DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg is convinced that a sinister reason lies behind the disappearances of 38 women. Gemma Piper and other supervistory staff are less convinced, arguing that adults are allowed to drop out of sight if they wish to. But there is a common victimology here: all of these women were successful and independent, and distinctly not the sort to simply abandon their families and their careers.

Heck’s persistant enquiry soon leads him into the murky underworld of organised crime. It’s not unfamiliar territory to him, but even Heck is shocked when he hears about a mysterious, semi-mythical syndicate called the Nice Guys’ Club, who serve a purpose that is beyond anything he has ecountered to date …

SACRIFICE(ebook £2.99)

SACRIFICE(ebook £2.99)The Serial Crimes Unit is unleashed in full force when a ‘calendar killer’ begins to claim random victims. The so-called Desecrator is the worst kind of predator (or more likely, group of predators). Faceless and nameless and, initially at least, motiveless, he/they prowl the length of the country, abducting targets of convenience and, on special days of the year – Christmas Day, Good Friday, St George’s Day etc – sacrificing them in horrific but apparently meaningless rituals.

Heck is only one part of the team despatched to apprehend the maniacs, but he is the first one to deduce that these slayings, gruesome though they are, are only the build-up to something infinitely more terrible …

THE KILLING CLUB

THE KILLING CLUB

(ebook £1.99)

Heck is used to attending crime scenes that are bloodbaths, but this new case is something else. Two years ago, dozens of victims were claimed in a series of ghastly abduction murders, massacred by the so-called Nice Guys’ Club, Britain’s most terrifying gang. Now, it seems, the survivors of the gang are back and hellbent on slaughtering anyone they consider a potential danger to their organisation.

The case is thus reopened, and Heck is spoiling to get involved so that he can properly finish the job he started last time. However, for various reasons, Gemma Piper, doesn’t want him anywhere near this enquiry. There is too much bad blood involved, and it has to be dealt with professionally. Heck can’t agree. He is desperate to get to grips with the Nice Guys again, even if it means going AWOL …

DEAD MAN WALKING

DEAD MAN WALKING

(ebook £1.99)

After a spectacular fall-out with his bosses, in particular Gemma Piper, over their handling of the last case, Heck sought reassignment away from the Serial Crimes Unit, and has been transferred to the Cumbria Police, where he now works as the sole detective in the beautiful but remote Langdale Pikes.

It’s pretty routine work until some teenage hikers go missing, all the evidence pointing to a killer whom UK law enforcement thought dead and buried long ago. The ‘Stranger’ was a whistling madman who used to accost young couples parked up in their cars, raping the women and then killing both them and their lovers. During an undercover sting, Gemma Piper, then a DC, served as an armed decoy and shot and badly wounded the assailant, who was swallowed in a Dartmoor mire as he attempted to flee.

This was years ago of course, and at the other end of the county. Could the killer really have reappeared now, and in the Lake District of all places? Gemma thinks it’s unlikely, but joins Heck in the Langdales to look into the case, just as the thickest, coldest fog of the winter descends.

HUNTED

(ebook £1.99)

HUNTED

(ebook £1.99)Readmitted into the Serial Crimes Unit, Heck is despatched to an affluent rural corner of Surrey, where, as a favour to Gemma Piper, he investigates the death of one of her mother’s business colleagues in a bizarre and unlikely accident. However, Heck soon becomes suspicious about the pattern of events surrounding the fatality.

Partnered with spiky local detective, Gail Honeyford, he uncovers a trail of unusual and outlandish fatal accidents that leads all over the south of England: a pair of thieves bitten to death by poisonous spiders, a driver impaled through the chest by a scaffolding tube, etc.

Could a calculating mind be behind these weird events? And if so, why? Surely to God, Heck is not investigating a series of elaborate, life-threatening pranks?

ASHES TO ASHES

(ebook 99p)

ASHES TO ASHES

(ebook 99p)John Sagan is a forgettable man. You could pass him in the street and not realise he’s there. But then, that’s why he’s so dangerous.

A torturer-for-hire, Sagan has terrorised – and mutilated – countless victims. He’s also murdered a police officer. And now, with London too hot for him, he’s on the move. Heck must chase the trail, even when it leads him to his hometown of Bradburn, on the industrial outskirts of Manchester, a place that holds nothing but unhappy memories for him.

But John Sagan isn’t the only problem. Bradburn is currently embroiled in a drugs war, which has unleashed another killer on the community, a maniac who burns his victims to death with a flamethrower. When Heck arrives home, a place he never thought he’d set foot in again, it has quite literally become a fiery hellhole …

KISS OF DEATH

(ebook 99p)

KISS OF DEATH

(ebook 99p)In a time of swingeing police cuts, Gemma Piper seeks to save her unit by charging them with bringing in 20 of the UK’s most wanted fugitives. Heck and Gail’s target, a notorious bank robber and kidnapper, takes them up to Humberside, but here they uncover a piece of footage which appears to depict their fugitive in a desperate fight for his life.

Heck realises that there’s another player in this game of cat and mouse, and that whoever it is, they’ve not just caught the prize this time, they’ve made sure that no one else ever will.

How far will Heck and his team go to protect some of the UK’s most brutal killers? And what price is he personally willing to pay?

LUCY CLAYBURN

Lucy is a divisional detective constable in the fictional Crowley district of inner Manchester, officially known as November Division. It’s a rough, tough beat, and Lucy, a blue-collar girl through and through, is constantly challenged – but not just by the villains, often by her colleaues as well. Her position is made even more difficult because, though she never knew him during her childhood, she has recently been reintroduced to her estranged biological father, Frank McCracken. He was only a doorman thirty years ago, when Lucy was first conceived, but he’s now advanced through the criminal ranks until he’s becomes a major player in the Crew, one of Northwest England’s premier syndicates. For mutual benefit, both father and daughter keep what they’ve learned about each other secret, but obviously their relationship has changed. Lucy, a good cop at heart, now finds herself walking a tightrope through the world of organised crime.

As with Heck, here is the full series in the correct order, and again, I think you’ll find that they are all pretty reasonably priced.

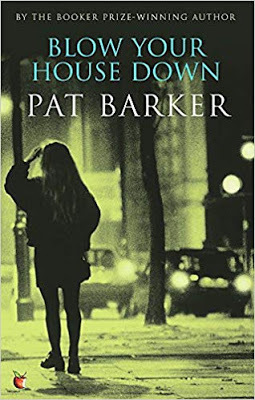

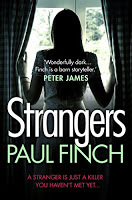

STRANGERS

(ebook £1.99)

STRANGERS

(ebook £1.99)Though she’s now been a decade in the police, PC Lucy Clayburn is struggling to make a mark in her job. She dreams of being a detective, but four years earlier, on her first CID assignment, she made a castastrophic error and a fellow officer nearly died.

Now, however, a new chance comes up. An impressive opportunist arrest brings her to the attention of the no-nonsense Detective Superintendent Priya Nehwal, who is covertly investigating the unique case of a female sex predator, possibly a deranged prostitute who has been brutally murdering her male clients. Once the press get hold of the story, they nickname this bizarre killer: ‘Jill the Ripper’.

Lucy joins the investigation team, but in the first instance, must go undercover as working-girl herself, which takes her into a backstreet world of drugs, petty crime and casual sex and violence. It also leads her to SugarBabes, a secret brothel controlled by the Crew, an infamous Manchester firm, where just about anything is available for the right price …

SHADOWS

(ebook £1.99)

SHADOWS

(ebook £1.99)Now re-established as a detective constable but struggling to deal with the private knowledge that her stranged father, Frank McCracken, is a senior lieutenant in the Crew, Lucy Clayburn still leads a difficult day-to-day existence.

However, very unexpectedly, a case then comes along that, for once, might put she and her father on the same side.

A spate of violent robberies, in which the victims are always shot in the legs afterwards, rocks the borough. It’s a complex case to investigate, even more so because those attacked are invariably members of the underworld. However, whether she likes it or not, Lucy now has a good contact in McCracken, and both have a vested interest in stopping this crimewave.

The problem is … they have very different methods.

STOLEN

(ebook 99p)

STOLEN

(ebook 99p)No one in the higher echelons of Crowley CID believes in the existence of the so-called ‘black van’. Initially held to be an urban myth, the van has supposedly been seen prowling by night across various housing estates in Crowley, and always at a time when local pets have been abducted.

Even if this thing is real, the disappearances of cats and dogs is hardly a major issue for the police. When Lucy Clayburn, acting on a tip-off, cracks a local dog-fighting ring, she thinks she has solved the mystery. However, even on arresting the miscreants and searching their property, there is no sign of the black van or any of the pets reported missing.

Maybe this mysterious vehicle is nothing but a legend after all?

But then there are more abductions. And this time it isn’t animals. This time it is people, firstly the homeless, then OAPs, and finally – after all, the nameless abductors have now got in much valuable practise – the young and able-bodied. And each time, Lucy learns, a strange van has been seen in the vicinity.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly liked … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE PUPPET SHOW

THE PUPPET SHOW by MW Craven (2018)

England’s beautiful Lake District is not the sort of place where you’d expect a serial killer to start claiming victims. But when it does, given the small local police force and restricted road infrastructure in such a wild and mountainous part of the country, it’s a real nightmare.

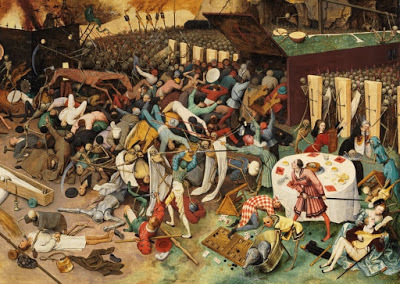

The Immolation Man, as he has soon been dubbed, has embarked on a reign of terror, during which he kidnaps seemingly random victims (though all of them are older men), holds them prisoner for weeks in some out-of-reach place, and then brings them to their chosen place of execution – each time a different circle of standing stones on Cumbria’s wind-scoured hills – where he douses them with a cocktail of highly flammable chemicals, and burns them alive.

The last person who ever thought he’d be asked to participate in the resulting enquiry is Lake District native and ex-Black Watch squaddie, Washington Poe, even though he is currently living in embittered, self-imposed exile in a rundown farm on Shap, one of the higher, more remote Cumbrian fells. Until recently, Poe was a detective inspector in Scotland Yard’s National Crime Agency, and a highly regarded investigator whose rough and ready methods have often been overlooked because he gets results. However, even Poe can go too far sometimes, and he is currently suspended and basically disgraced after acting on principle in a previous investigation rather than following procedure, the pending outcome of which may see him discharged from the police force altogether.

Poe, furious with all his former colleagues, probably wouldn’t assist in the enquiry even if he was asked, but then the NCA’s Detective Insepctor Stephanie Flynn turns up and advises him that yet another victim has been found, and even though, like all the rest, this one is middle-aged and male, there is a big difference this time as a name was branded into his chest before he was burned – and that name is ‘Washington Poe’.

Realising he has no option but to get involved, Poe accepts reinstatement into the NCA (even though not all of its top brass approve), and even takes a demotion in rank from DI to DS (though this latter is because Poe rarely works within the normal structures of high-level police investigations anyway, usually preferring to develop his own leads and run them down under his own steam).

Straight away, however, he finds himself up to his neck in unforseen complexity. To start with, this is no ordinary serial murder case. There is more than just cruelty and sadism on show; ritual elements are in evidence too, while the offender is highly organised and efficient. Given that the most recent victim was a local councillor, Michael James, there may even be a political dimension. It’s therefore quite a relief when he is partnered with NCA civilian intelligence analyst, Tilly Bradshaw, an expert computer programmer and online researcher, though whatever she possesses in intellect is balanced out by her astonishing naivety and distinct lack of people skills. In short, Bradshaw is something of an oddball and, as such, is shunned and/or mocked by her civie colleagues while other police officers, even the kinder ones, would rather not work with her.

However, thrown together in this whether they like it or not, and both of them outsiders to a greater or lesser extent, Poe and Bradshaw find that they are natural allies, and, mainly thanks to Poe’s perceptive approach when it comes to dealing with his curious new partner, they quickly form an effective if somewhat eccentric working relationship. And this, of course, can only be a good thing, because the Immolation Man is clearly not going to stop killing.

Needless to say, the deeper the twosome dig into the case, the more horrible revelations they uncover, the more extensive the apparent conspiracy at the root of it, and the closer and closer to home the enquiry seems to bring them …

There are three main things that I really liked about The Puppet Show , I mean apart from it being an intriguing, suspenseful and excellently written thriller.

First of all, its setting is marvellously realised. Bleak, rugged locations are not uncommon in crime fiction, especially since the arrival of the Nordic Noir subgenre, but the Lake District, while rugged, is not bleak. It’s astonishing in its Alpine grandeur, its pristine lakes, its enormous skies and awesome weather (sun, snow or rain, you know when you’re in the Lakes). In addition, it’s atmospheric in its ancientness (megaliths, stone circles and prehistoric tumuli are only part of the story), and also in its quaintness; Cumbria’s lakeside towns, in sharp contrast to the fortified farms (a legacy of the reiver clans of old) and tumbledown crofts on its high fells, are ultra civilised, filled with libraries, theatres, art galleries, craft markets, museums, cosy pub/hotels and first-class dining.

And all of this, every aspect of it, is captured in The Puppet Show .

We shouldn’t be too surprised, of course. MW ‘Mike’ Craven hails from that part of the world, and he clearly knows his homeland intricately. And yet, he doesn’t go heavy on all this. The Puppet Show is not a Lake District National Park tour-guide. We do manage to travel all over it during its action-packed 342 pages, but it’s all relevant, and it informs the plot. We’re not just sightseeing here. This is a cop-thriller first and foremost, and yet Lakeland is always there, an extra character, if you like, but an important one too. I can honestly say that I don’t think I’ve read any book that it is as wrapped quite so effectively and at the same time so non-intrusively in its environment.

The second thing I really liked is The Puppet Show’s authenticity.

Mike Craven was a probation officer before he became a full-time author, so you’d expect him to know his stuff. And he really does.

In this novel, though the Lake District is a remote region, modern policing is to the fore. This is the National Crime Agency after all, possibly the most modern outfit, in every sense of the word, in the whole of the British police service. But again, Craven doesn’t overdo this. All the procedures are there, all the latest methods and the brand-new technical back-up are duly referenced, but none of it gets in the way.

In fact, if anything, through the proxy of Washington Poe, Craven vents his frustration at this. Electronic form-filling, divisional protocols, legal minutiae and other types of 21st century officialdom all feel like unnecessary jobsworthisms to Poe, who’s the kind of cop who just wants to get out there and investigate, to use boot-leather and common sense. He particularly despises the kind of bureaucratic red tape that prohibits officers from exercising judgement and discretion.

Yes, it’s all here in The Puppet Show , the complete present-day police experience. On one hand you have the super-efficient, super hi-tech and yet hidebound world of the National Crime Agency, as exemplified by patrician Director Edward van Zyl and even more so by Deputy Director Justin Hanson. And on the other, you have the lone-wolf detective, Poe, who’s not a maverick – he’ll happily play by most of the rules – but who is so eager to get the job done that he’s as frustrated by the etiquette of modern policing as he is by the villains.

I say it again, Mike Craven was a probation officer, not a cop, but he clearly worked with the cops. Because from this debut novel, he knows his stuff inside-out.

And this, I guess, brings us neatly to the characters, which are the third aspect of this novel that I really enjoyed.

There are two main personalities here, Poe and Bradshaw, and what a unique pairing they are.

Indicrectly, we’ve already assessed some of the most appealing aspects of Washington Poe. He’s basically a man’s man, gruff; self-reliant, a little taciturn, but affable too in the right company. A fairly typical male character, I suppose, in the world of cop writing, but that’s only half of the story.

Because while Poe is the primal creature, the elemental force, the instinct-over-analysis, Tilly Bradshaw is the cerebral side of the equation. And together, they make a near-perfect whole.

But Bradshaw has her own personality, too, and it was a fascinating decision by the author to place at the heart of a story like this, which has the potential to be hugely distressing (to the readers, yes, but also to the characters in the tale, particularly those with some political acumen), a character who is introverted and overly sensitive, who is untrusing of others, has very little self-awareness and is even slightly autistic. And she’s not been brought in purely to be a victim. Far from it. I mean, she is victimised on occasion, as anyone in that situation would be in real-life, but Poe, though he at one point strong-arms someone who’s been relentlessly bullying her, does not fall into the role of permanent bodyguard. Bradshaw does not need that. She is incredibly smart, possessing great deductive powers, and is very computer-literate. In the modern age of policing, these are vital assets.

In purely technical terms, of course, this is a clever device by Craven. In future books, I can easily envisage Poe coming to rely heavily on Bradshaw, not just as his quick hook-up to the internet and personal mine of information, but also as his thinker and adviser. But that’s not all it is. The relationship is charming and works very well at a narrative level, the bullish Poe disarmed by Bradshaw’s innocence, the nervous Bradshaw reassured by Poe’s strength and energy. They’re hardly peas in a pod, but such is the skill of the writing that their relationship develops throughout The Puppet Show in a pleasing and completely convincing way.

Overall, this novel is a long way from being your average serial killer thriller. It’s never what it seems, twisting and turning continually, and moving at great pace. And of course, you’ve got that wonderful backdrop too, and that feeling that this is the real deal – that this could happen exactly as Craven relates it Then you’ve got those characters, whom you empathise with from the word ‘go’.

In short, The Puppet Show is a compelling crime novel, very upbeat in its outlook, very modern, and very entertaining. It needs to sit on each and every bookshelf.

And now, as always, in anticipation of its inevitable development for film or TV (the Lake District is begging for its own cop show), I’m going to be a cheeky sod and try to cast the main parts in this beast. You never now, at some point, some producer or casting director may take heed of this column. Anyway, just for laughts, here we go:

DS Washington Poe – Nick BloodTilly Bradshaw – Ella PurnellDI Stephanie Flynn – Joanne FroggattDS Kylian Reid – Harry LloydGamble – Ron DonachieHanson – Adrian RawlinsVan Zyl – Mark GatissBishop Nicolas Oldwinter – Richard Wilson

Hilary Swift - Maria Doyle Kennedy

(The image at the top of the column comes to us from the horror movie, THE HILLS RUN RED, and is unconnected to any of these titles. Sorry about that, but you must admit, it fitted the headline).

Published on July 09, 2019 07:59

May 31, 2019

Back on the chiller trail: more eerie places

It may seem odd but even though it’s the first week of June, I’ve been thinking autumnal thoughts this week. That’s because I’m going to chat a little bit about an autumn-set novella of mine, SEASON OF MIST, from 2010, which I intend to reissue both in print and ebook form around September / October this year. It’s both a thriller and a horror rolled into one, with strong folkloric elements, with means that talking about it now ties in neatly with another bit of fun I’ve got lined up for today.

I’ve been doing another of those gazetteers of STRANGE AND EERIE PLACES, but this week, instead of the UK and Ireland, which I’ve already done, I’ll be focussing on WESTERN EUROPE.

In addition to those two treats, and because we’re exclusively talking weird, scary mysteries today, I’ll also be reviewing and discussing Simon Stranzas’s intriguingly strange and spooky anthology, AICKMAN’S HEIRS.

If you’re only here for the anthology review, that’s fine. Just pop down to the lower end of today’s blogpost; that’s where all my reviews go. However, if you’ve got a bit more time, perhaps you’ll like to stick around at this end a bit longer. Especially as I’m now about to discuss …

Season of Mist

Back in 2010, I penned a bunch of original horror novellas, which were all published together in one book, WALKERS IN THE DARK, by Ash-Tree Press, and launched at World Horror in Brighton. The book got quite a few good write-ups, but alas, a decade later it’s no longer in print.

However, one of the stories in there, SEASON OF MIST – which clocked in at 40,000 words – was almost classifiable as a short novel in is own right, and I reckon it’s time it saw the light of day again.

However, one of the stories in there, SEASON OF MIST – which clocked in at 40,000 words – was almost classifiable as a short novel in is own right, and I reckon it’s time it saw the light of day again.Back then in the early 2000s, I was mostly writing horror and science-fiction (mainly Dr Who). I hadn’t at that stage developed a profile as a crime novelist but was increasingly drawing on my police experience to develop thriller concepts. However, when the idea for SEASON OF MIST popped into my head, it allowed me to wear two hats at once, giving me the opportunity to link my long-standing interest in folk-horror with the kind of brutal crime story that is all too real in Britain today and was equally real when I was a youngster in the early 1970s.

One particular memory of that long-ago decade still sticks in my mind: the autumn of 1974, when the preparations for Halloween in my hometown of Wigan, Lancashire, were made particularly scary by a local rumour that a child-killer was on the loose. In reality, there was one murder, and it did occur on a dark October night not too far from our patch. A bunch of teens had been playing hide and seek in the vicinity of a derelict hospital; one of them disappeared during the course of the game and was later found cut to pieces. It’s difficult to trace the details now, but I understand that the murderer was eventually arrested and turned out to be a mentally ill vagrant, who was then locked away in a secure institution.

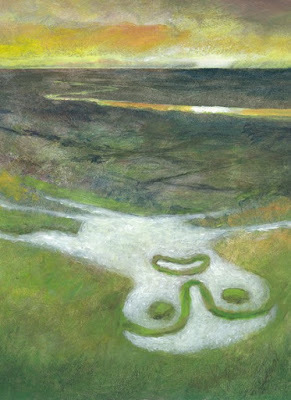

Of course, as children, the true facts of the tragedy didn’t trouble us. We were just awe-stricken by the raw horror of it. You see ... we too would shortly be dressed in Halloween garb and running around the darkened streets, woods and derelict mills and coal-tips that dotted our borough (like this one above, thanks to Dave Attrill). And this time, of course, it would be even more frightening than usual because now a real monster was on the loose.

Of course, as children, the true facts of the tragedy didn’t trouble us. We were just awe-stricken by the raw horror of it. You see ... we too would shortly be dressed in Halloween garb and running around the darkened streets, woods and derelict mills and coal-tips that dotted our borough (like this one above, thanks to Dave Attrill). And this time, of course, it would be even more frightening than usual because now a real monster was on the loose.The chilling memory of that long-distant Halloween Night, which was every bit as terrifying as we’d expected it to be, but which thankfully saw no one else actually die, lingered long for me – primarily because as well as being electrifyingly scary it was also hugely enjoyable, the perfect Halloween in fact.

Of course, simply recreating those actual events for SEASON OF MIST would not have been good enough. A much better idea, it seemed to me, was to combine them with an especially uncanny bit of Wigan mythology, as related to me when I was a tiny tot by my coal-miner grandfather.

According to local folklore, Red Clogs was an evil spirit that roamed the colliery wastes of our town, after a terrible underground disaster claimed the life of a collier, taking his feet in the process. In the isolated world of that 1970s industrial heartland, we were all fearfully familiar with this evil and remorseless entity … whose mythical depredations could easily, in the eyes of a bunch of innocent children, have masked the presence of a real serial killer.

SEASON OF MIST was the result. As I say, it’s a 40,000-word novella, which I’ll be looking to republish both in electronic format and in print as the autumn of the year approaches. So, watch this space.

Eerie places

Now, as promised, some other stuff ...

A few months ago, on January 9, I posted a blog – My Own Gazetteer of Strange, Eerie Places. It was a round-up of my top 20 strange and scary places in Britain and Ireland. Places I’d love to visit in my fiction, or, in one or two cases, places that I already had visited.

It proved to be a popular post; it received a lot of hits, and there were lots of positive and interested comments on Facebook and Twitter.

Given that people apparently liked it so much, it seems like an obvious next step to do the same thing again, only now to venture beyond the boundaries of the British Isles, in fact maybe to take this show all over the world, though obviously we can only visit one geographic region at a time.

I thought I’d start the ball rolling this week with Western Europe.

It’s one of the oldest constantly inhabited regions on Earth, it has a long, complex history (much of it blood-soaked), and there is literally a wealth of legend and folklore to get our teeth into. It’s also a corner of the globe where many truly ancient monuments have been lovingly preserved.

I should say straight away that I’ve had to be sensible with the number of places which for these purposes I’ve considered to be part of Western Europe. It could never be as simple as drawing a new line of longitude down the centre of the continent and treating everything to the west of it as fair game. For one thing, it would take forever to research so many potential venues, and for another, even opting only to include the very best, I’d finish up with many more than 20. So, I’m going to be discerning, and, as in the future I intend to write separate blogs about the eeriest, scariest places in Scandinavia, the Mediterranean and so forth, today I’m looking exclusively at Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, Switzerland and Austria.

So, without further ado, please enjoy (and feel free to comment on):

GAZETTEER OF STRANGE, EERIE PLACES 2: WESTERN EUROPE

1 Beelitz-Heilstätten

A district of a historic town in Brandenburg, eastern Germany, and home to an infamous abandoned hospital complex, some 60 buildings strong and for the most part accessible, which for years now has enabled members of the public to enter it at will, holding night-time vigils and taking multiple eerie photographs. Despite its exceptionally grim appearance – numerous film companies have shot footage here, making full gruesome use of the endless bleak corridors and rubble-strewn, graffiti-covered treatment rooms – the 100-year-old ruin has no specific reputation for occult or supernatural activity, though like all derelict medical complexes, it possesses a distinct aura of misery and melancholy. If it adds kudos, past patients include arch-villains Adolf Hitler and Erich Honecker. 2 Chateau Champtoce

It isn’t much to look at today – there’s scarcely enough of it left to be haunted – but Chateau Champtoce in Maine, central France, was one of several castles belonging in the early 15th century to legendary warrior, warlock and serial child-murderer, Gilles de Rais. A hero of the Hundred Years War and right-hand man to Joan of Arc, Gilles de Rais later retired to private life, where he is said to have sunk into a quagmire of depravity. At least 80 peasant boys, but maybe as many as 600, are said to have been lured into his various castles, where they were sodomised, sexually tortured and murdered, sometimes amid hellish Satanic rites. De Rais was hanged and burned in 1440, and though debates rage about the extent of his guilt, some claiming that the Church framed him, most historians consider him guilty as charged.

3 Lisbon backstreets

Though Portugal is regarded as a holiday idyll, it suffers severe social problems that most visitors never see. Some 2.6 million of its inhabitants live below the poverty line, and many of its larger cities’ most run-down neighbourhoods consist of slums and shack housing where drugs and crime are rife. One scary myth emerged in Portugal’s capital, Lisbon, several years ago. It concerned an unknown gang who would prowl the most deprived neighbourhoods late at night, leaping on random victims and offering them death, a beating or ‘a clown face’. Most opted for the latter, unaware that it meant the sides of their mouths would be slit, creating horrific Joker-like visages. It’s a very spooky story that has legs even today, even though it was discredited in 2009, when police and health services failed to locate a single record of any such assault victim.

4 IM Cooling Tower

The much-photographed Power Plant IM has been disused since the early days of this century, and though scheduled for demolition and regularly patrolled by security guards, still stands tall in the Belgian town of Charleroi, a dangerous, dystopian edifice beloved by urban adventurers. Originally built in 1921, it was for a brief time the biggest coal-burning plant in Belgium. Incredibly, despite its antique status, it continued to function – albeit with various modern adaptations – right through until 2006, when its excessive C02 emissions led to a protest by Greenpeace and its closure the following year. It presents us with another totemic Western European structure, which though incredibly eerie to look at has no actual history of odd or uncanny events. But check it out. It can’t really be excluded from a list like this, can it?

5 Castle Frankenstein

Yes, this is it, the original one-and-only Castle Frankenstein. It stands in the Odenwald mountain range in western Germany and was the official home of the powerful Frankenstein family from 1250 to 1662. It fell into ruin in the 18th century and remains in that state to this day. The Odenwald are heavily wooded and the centre of many legends, including one tale that a local alchemist, Johann Dippel, who lived in the castle after the Frankensteins had vacated it, dug up a corpse and brought it to life with black magic. Stories that Mary Shelley was inspired by this nightmarish folk-tale are doubted, some scholars claiming that she was never even in the region. That aside, the castle is reputed to be the centre of much paranormal activity and is regularly the site of televised Halloween and Walpurgis ghost-hunting events.

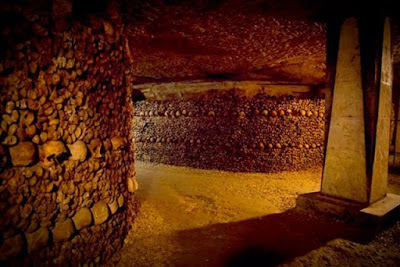

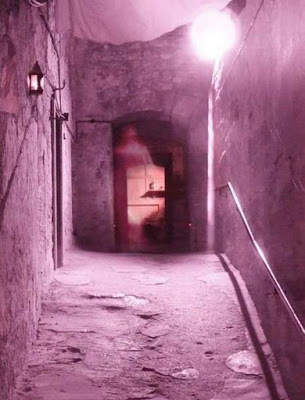

6 Paris Catacombs

All kinds of urban myths surround this infamous network of ancient underground ossuaries. One holds that hidden in its darkness is the entrance to Hell, another that diabolical sects convene here, and yet another that it is filled ghosts who only make themselves known after midnight, attempting to lure lonely explorers into the depths. What is fact is that over 6 million human remains are interred here. If that isn’t unnerving enough, a video camera was once found down here containing footage which indicated that the cameraman, who was never seen again, was being chased by something. Stranger still, on another occasion, a fully-equipped cinema was uncovered by police, complete with working phone-lines and cameras that were filming them; the cinema’s creators were never located, but a note was left, which said: ‘Don’t search!’

7 Chateau Miranda

Sadly, it was demolished in 2017, so no one can ever visit this famous neo-Gothic castle in the Namur region of Belgium again, but if wasn’t one of the scariest looking buildings in all of Western Europe, I’d be astonished. Though construction commenced in 1866, it was 1907 before it was completed, and its owners, the aristocratic Liedekerke-De Beaufort family, only occupied it until WWII, at which point it was taken over by German forces. Though it survived that era intact – it even survived the Battle of the Bulge! – the family never returned, and it became an orphanage and hospital before abandonment in 1991, from which point it was the focus of urban explorations and ghost hunts. Unfortunately, amazingly even, it was never known for its supernatural activity, but looking at it today it surely should have been.

8 Fribourg Forest

Not many of us would associate Switzerland with scary places given the general magnificence of its Alpine landscape. Most pictures from rural Switzerland strike us with awe rather than fear, but then in 2013 the newspaper, Le Matin , acquired this picture of a mysterious being known as Le Loyon, a weird giant wearing a boiler suit, cloak and gas mask, who for the previous decade had reportedly been seen wandering the paths in Fribourg Forest, in western Switzerland, terrifying all those who encountered him. The story was taken seriously by both local law enforcement and the press, though no assault or threatening behaviour was ever reported. Initial fears that Le Loyon was an alien or some kind of cryptid have now been dismissed as more recent sightings suggest the ‘giant’ is only slightly over 6ft tall.

9 Two horrors for the price of one

Two streets in the vicinity of Paris. Very pleasant, very unthreatening. Except that both – the main road in Gambais, a rural commune in the Île-de-France (top), and Rue le Sueur, a stone’s throw from Avenue des Champs-Elysées (bottom) – have a chilling past. The former housed Henri Landru, known as ‘Bluebeard’. A ‘lonely hearts’ predator, Landru seduced single women, who he’d lure back to his home, where they’d be killed and dismembered. By 1919, he’d murdered at least 11, though police failed to trace a further 72 that he’d been in correspondence with. In Rue le Sueur meanwhile stood the home of Marcel Petiot, who during WWII tortured and murdered at least 23 desperate folk he’d lured there, having promised them escape from the Occupation (though his real total was more like 60). Both killers died on the guillotine, unrepentant to the last

10 Woods of Eefde

The peaceful woodlands surrounding the village of Eefde in the East Netherlands province of Gelderland are a singularly pleasant place, but are also said to be the haunt of the Witte Wieven, which literally means ‘the white women’. They are the centre of a mysterious rather than frightening Dutch legend, which holds that herbalists, midwives and other valued village wise women would, after death, be buried with full honours and their grave sites venerated afterwards. As such, their spirits would rise and wander the locality, offering assistance and hindrance depending on the worthiness of whichever person came into their path. The belief appears to stem from the Dark Ages, wherein pre-Christian tales of Elves were woven in with Church teachings about the afterlife. Eefde is renowned for its ‘white woman’ activity.

11 Chateau de Raray

Possibly the ultimate fairy tale manor house, Chateau Raray in Picardy (as famously photographed above by Simon Marsden), is an exclusive hotel and golf course these days, so you’re unlikely to turn up there and feel creeped out in any way. But if the current building, which dates back to the early 18th century, doesn’t overwhelm you with its otherworldly atmosphere, then the myriad gardens, arches, shaded walks, and rows of busts and statues surely will. It’s no surprise that in 1946, avant-garde film-maker Jean Cocteau chose it as the location for many of the exteriors in his haunting masterpiece, La Belle et la Bête . That said, it isn’t just an embodiment of magic and mystery. A couple of particularly eerie tales hold that the main building is haunted by the ghost of a servant girl who hanged herself, and the gardens by a statue that moves around at night.

12 Kampehl

From the sublime now to the grotesque, in a rural church at Kampehl in northeast Germany. Here, you’ll find an open coffin and in it, the mummified corpse of Christian Kahlbutz, an ill-tempered landowner of the 17th century, who, when accused of murder, swore that if he was guilty of the charge, God would never let his corpse rot. He died of natural causes in 1701, but in 1794 workmen re-opened the vault and were stunned to discover the uncorrupted corpse. All kinds of myths are attached to it, including a tale that during Napoleonic times, some French soldiers attempted to crucify it in the village centre, but that it became animated in its outrage, driving them away in terror. During the 20th century, two doctors autopsied the remains, but were unable to explain their non-deterioration.

13 Porte de Martray

The last of the medieval gateways to the city of Loudun in southwest France. Loudun was the scene of extraordinary events in 1634, as made famous by maverick movie-maker, Ken Russell. Though a lurid take on the true events, his controversial 1971 movie, The Devils , was largely accurate in its portrayal of a religious town in the grip of Satanic panic. When members of the local Ursuline convent accused non-celibate priest, Urbain Grandier, of sending demons to sexually torment them, a brutal enquiry followed, resulting in Grandier’s torture and eventual burning at the stake in the town square. Though an impressive document survives, purporting to show Grandier’s written pact with Lucifer, historians blame mass hysteria by the nuns and political contrivance by Grandier’s old foe, the lethal Cardinal Richelieu.

14 Salzburg

The wonderfully baroque capital of Austria, Salzburg, can boast a plethora of ancient eerie tales, but supernaturalists are best advised to visit it during the Christmas season, when the Krampus and Perchta parades are held. It’s a well-loved costume event, but visitors are often unnerved as the shaggy, horned brutes rampage down the snowy streets, snorting and roaring. Krampus, now familiar to non-Tyrolean audiences via Hollywood, is seen as a kind of anti-Santa, a monstrous being that takes away naughty children rather than rewards those who are nice. Perchta, meanwhile, appears as a half-animal hag, whose purpose is also to terrify and punish those who haven’t performed well during the year. Both are believed descended from winter gods that were worshipped and feared in the mountains during the pre-Christian era. 15 Dadipark

Dadipark is no longer with us, having been demolished in the last couple of years and turned into a green recreational zone, but the one-time amusement park just south of Antwerp, in Belgium, was a derelict, overgrown edifice for the best part of two decades, having been forced to close after an increasingly gruesome series of accidents. Opened in 1950, initially as entertainment for children whose parents had made pilgrimage to the Dadizele basilica, it was one of the first of its kind in Europe, and soon grew into a huge operation, though safety concerns were continually aired as a succession of nasty incidents left visitors injured. When a child lost his arm in 2000, it was the final straw. The park stood empty and decaying for many years, countless ghost stories celebrating its eerie, desolate appearance.

16 Montsegur

The last stronghold of the Albigensians, Montsegur is a mountain-top castle, which like so many of its kind in southern France is remarkably well-preserved (though in truth, it is much rebuilt). Overlooking the beautiful Languedoc, it is riddled with ghostly tales – spectral mists, whispering voices and shadowy figures – most of which allegedly relate to the atrocities of the Albigensian Crusade, which in the 13th century confronted the Albigensian (or Cathar) religion, a radical offshoot of Christianity declared heretical by the papacy. The campaign was earmarked by numerous slaughters, though it ended in 1244, at Montsegur, where the last of the Cathars were holed up. After surrender, all 244 survivors were burned alive in a gigantic bonfire down in the valley. The site is still known as the ‘Field of the Burned’, and on dark nights, distant weeping can allegedly be heard.

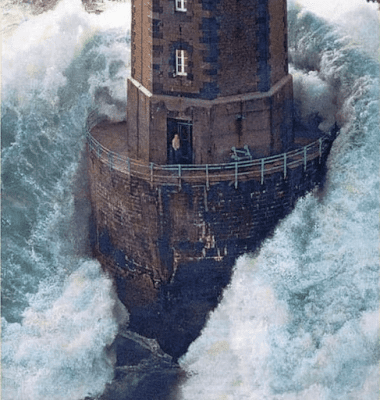

17 La Jument lighthouse

Made famous by this incredible photograph taken by Jean Guichard in 1989, the La Jument lighthouse was always considered one of the most dangerous postings in the world. Located off the coast of Brittany, it was an area long notorious for huge seas, roaring waves and catastrophic storms. Before the lighthouse was even built, there were numerous wrecks on the nearby coast. Between 1888 and 1904 alone, 31 ships went down there. These included the 1896 sinking of the SS Drummond Castle, which cost 250 lives. Even after the lighthouse was opened in 1911 (its construction delayed by a procession of incredible storms), there were repeated reports of it being inundated by waves, windows shattering, furniture washed out to sea, keepers only just surviving. It still stands today but is now fully automated.

18 Palais Garnier

The Palais Garnier opened in 1875 to house the Paris Opera, and still stands today in all its opulent glory. One of the most famous opera houses in the world, the Palais Garnier was named after its architect, Charles Garnier, and was a grandiose structure, both inside and out. However, it was put on the map once and for all by Gaston Leroux’s 1910 novel, The Phantom of the Opera . Everyone knows the famous story, but few know that Leroux based many of its key elements on allegedly true melodramatic tales concerning the Palais Garnier. There is a huge underwater reservoir, though not quite a candlelit lake, while staff often blamed odd accidents on a resident ‘Phantom’. There is even a story that a missing actress’s bones were found locked in a cellar trunk many years after her unexplained disappearance.

19 Moosham Castle

Moosham Castle is a well-preserved medieval fortress in eastern Austria. Privately owned today, though some sections of it are open to the public as art galleries, it is a peaceful, scenic place, and yet its history comprises some of the grimmest events ever put on record. Already the centre of numerous baronial feuds during the Middle Ages, in 1675 the Zaubererjackl witch trials were held there, which eventually saw 139 people, most of them men but many of them children, hanged, burned and strangled. Others were spared death, but branded and mutilated (their hands chopped off). The bloodshed didn’t end there, the castle becoming the centre of a werewolf scare in the early 1800s, when hundreds of animals were found torn and half-eaten in the vicinity. Local peasants claimed the former evil had precipitated the latter.

20 Rennes-le-Chateau

A Pyrennean religious centre, which allegedly sits on a great mystery. The story starts with Bérenger Saunière, a humble priest who in the 1880s occupied this crumbling rural church, and yet went on not only to rebuild it lavishly, but to deck it with bizarre statues, including this chilling image of Asmodeus, and by the 1890s, to have spent over 650,000 francs doing so. Saunière died in 1917, never having disclosed this fortune’s origin. Some believe he practised simony, though there is doubt that the crime of selling Masses could ever have raised such a sum, while others insist that he found the treasure of the Cathars, and others that he had discovered documents proving that Christ’s descendants (yes, you heard that right!) had founded several lines of European kings – if true, you could only guess at the potential pay-off he could have demanded.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

AICKMAN’S HEIRS

AICKMAN’S HEIRS

edited by Simon Strantzas (2015)

An intriguing anthology of weird, open-ended tales, chilling in tone and concept though rarely indulging in blood and gore or utilising standard supernatural tropes, and written in homage to the late, great Robert Aickman, a British author of the 20th century, who specialised in the strange and macabre rather than the out-and-out horrific.

Rather than just tell you everything that happens from one story to the next, I’ll let Undertow provide the intro. Here’s their official blurb, which nicely hints at the enjoyable weirdness to come.

Edited by Simon Strantzas, ‘Aickman’s Heirs’ is an anthology of strange, weird tales by modern visionaries of weird fiction, in the milieu of Robert Aickman, the master of strange and ambiguous stories. Editor and author Strantzas, an important figure in weird fiction, has been hailed as the heir to Aickman’s oeuvre, and is ideally suited to edit this exciting volume. Featuring all-original stories from Brian Evenson, Lisa Tuttle, John Langan, Helen Marshall, Michael Cisco, and others.

Can strangeness in itself be scary? Probably not, though it can certainly be unsettling. And indeed, that was my main reaction to most of the contents of Aickman’s Heirs … a feeling that I was ill-at-ease, that I’d somehow been disturbed without really knowing how or why, and yet at the same time was deeply satisfied.

As that was also my reaction to much of Robert Aickman’s fiction (he wrote 48 short stories in total – many of which have become staples of ‘classic horror’ collections), then I can only conclude that editor, Simon Strantzas, and the numerous writers he has brought together for this book, have hit their main target quite successfully.

We have here an entire range of weirdness, most stories hinting at the grotesque rather than explicitly demonstrating it, and yet, though they rarely hit us with a killer last line or murderous unseen twist, always leaving us deeply discomfited.

Take Brian Evenson’s Seaside Town , in which a mismatched couple visit a French coastal resort where dreariness is the watchword, only for the male of the pair to be inexplicably abandoned by his partner, with no real clue where he is or why. Or Richard Gavin’s Neithernor , which sees a snobbish art critic determined to investigate when he uncovers evidence that his artistic cousin might be a hostage in the grotty little gallery in the next town.

Another key trait of Robert Aickman’s was his relentless merging of the mundane with the bizarre. Very illustrative of this, Ringing the Changes was perhaps one of the great man’s most famous and certainly most oft-reprinted tales, taking another awkward couple to another dull seaside town, this time on the English east coast during the off-season, settling them down in one of the most depressing pubs imaginable, and then filling the air with a clangour of church-bells which literally will not stop until the dead themselves have been wakened. Picking up the torch in Aickman’s Heirs , Nina Allan’s lengthy tale, A Change of Scene , pays direct tribute to the story, in some ways that I won’t mention here as that would be too much of a spoiler, though put it this way, it’s set in the same miserable town (spelled only slightly differently), features another strained couple – two lifelong friends this time, both widowed (again, one of them may have been in the original tale) – and has much to say about the resort’s curious number of church steeples.

Less recognisable, perhaps, but equally disquieting in its clash between the ordinary and the extraordinary is John Howard’s Least Light, Most Night , which sees a reserved, even rather shy office worker reluctantly accept a curious invitation to attend the house of a colleague whom he doesn’t know well for tea and biscuits, at which point he is drawn into a very odd world indeed.

Robert Aickman rarely missed a chance to evoke a dreamlike, often nightmarish atmosphere. And Aickman’s Heirs goes for this too, in a big way.

Take David Nickle’s Camp , which plucks a sophisticated newlywed gay couple out of the city and sends them on a do-it-yourself honeymoon in the Canadian wilderness, where a slow and terrible transformation commences. Or Lynda Rucker’s The Dying Season , wherein another couple trapped in a failing relationship visit a holiday resort so miserably rundown that it scarcely seems possible it could exist in the real world.

With all these stories, of course, and all the others contained herein – there are 15 in total – Aickmanesque ambiguity reigns supreme, solutions often left to the interpretation of the reader. Characterisation typically runs deep (though, at times, is complex – with loneliness and isolation key and repeating themes), while menace arrives subtly, much of the damage self-inflicted, our heroes beset by the results of bad choices and poor personal judgements.

Again like Aickman’s originals, the stories are expertly crafted and exquisitely written. You’d expect that from highly regarded professionals like Lisa Tuttle and John Langan, whose contributions – The Book that Finds You and Underground Economy , respectively, are among the best in the tome. But Camp is a particularly excellent example too, as are The Dying Season , A Change of Scene , and DP Watt’s deceptively gentle A Delicate Craft .

Don’t just take my word for it, though – check it out for yourself.

In fact, in this case you really should, because Aickman’s Heirs , like most of Robert Aickman’s own work, will probably divide horror fans. Those who always need a clear resolution, or who like to be jump-scared out of their skins, and of course those who consider themselves gore or splatter hounds, most likely won’t be enamoured. In many ways, the stories in here are literary shorts at least as much as they are horror – but if you have any interest in the ‘other’, that strange, outré world of speculative writing, where nothing is necessarily what it appears to be, messages are purposely mixed, and much of the quiet terror stems from frailties of the human psyche, then Aickman’s Heirs could definitely be an anthology for you.

And now …

AICKMAN’S HEIRS – the movie

Just a bit of fun, this part. No film-maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware), but here are my thoughts on how they should proceed, if they do.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances which require them to relate spooky stories.

It could be that they’ve all got lost in an underground catacomb and are then confronted by a mysterious monk (a la Tales from the Crypt) or are the subjects of memoirs related by a vampire to a famous horror author in an elusive and Gothic London club (al la The Monster Club) – but basically, it’s up to you.

It could be that they’ve all got lost in an underground catacomb and are then confronted by a mysterious monk (a la Tales from the Crypt) or are the subjects of memoirs related by a vampire to a famous horror author in an elusive and Gothic London club (al la The Monster Club) – but basically, it’s up to you.Without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

The Dying Season (by Lynda E Rucker): A gentle artist and her bullying corporate husband spend an off-season holiday at a drab seaside trailer park, which is almost empty except for the disturbingly strange couple across the way …Silvia – Emma DumontJohn – Toby RegboLynn – Ruth WilsonGabriel – Miles Jupp

Two Brothers (by Malcolm Devlin): When William’s older brother, Stephen, goes to boarding school, the younger sibling is left to his own devices in their big country house. He yearns for his brother’s return, but when Christmas arrives, and Stephen comes home, he has subtly changed …Father – Philip Jackson(Alas, my knowledge of child actors isn’t broad enough to effectively cast either Stephen or William).

A Delicate Craft (by DP Watt): A lonely Polish plumber looking for work in the English East Midlands meets and befriends elderly Agnes, who teaches him the delicate art of lace-making. A rare skill, for which there is a terrible price to pay …Boydan – Antoni PawlickiAgnes – Helen Mirren

Seven Minutes in Heaven (by Nadia Bulkin): A sulky 20-something is fascinated by her hometown of Hartbury’s eerie twin, Manfield, which still stands a few miles down the road despite having been evacuated after a pesticide disaster. In due course, she uncovers a terrifying truth …Amanda – Jessica Henwick

Published on May 31, 2019 01:50

May 16, 2019

The mental aberrations of sociopathic men

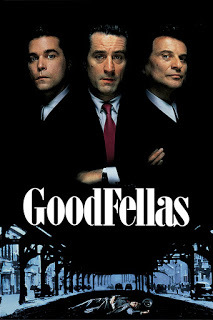

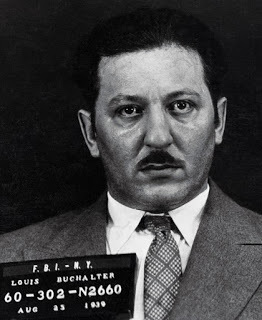

Well … it’s publication day for STOLEN, my third Lucy Clayburn novel, so I’m inevitably going to be talking a little bit about that today (but not too much, as I’ve gassed a lot about it recently). But given that there is lots of gangster stuff in STOLEN , including one massive underworld hit (which has certainly got one or two reviewers gossiping), I thought we might also chat a bit about gangland atrocities, and just as an academic exercise, that I’d single out the 10 MOST SHOCKING AND TERRIFYING that I’ve ever come across in real life.

On top of that, because today we’re looking deep into the mental aberrations of evil, sociopathic men, I’ll be reviewing and discussing CAIN’S BLOOD by Geoffrey Girard, which is as grim and disturbing as the modern crime thriller tends to get, but with sci-fi elements interwoven. If you’ve only called in to check out the Geoffrey Girard review, no problemo. You’ll find it at the lower end of today’s blogpost, as always. Feel free to zoom on down there ASAP.

However, if you’re also interested in the other stuff, stick around a little longer, and let’s talk first about …

Lucy Clayburn 3

I’m very happy to see STOLEN , the third novel in my Lucy Clayburn series, published today. This latest installment finds my young police heroine still working cases in Crowley CID, Crowley being the ‘November Division’ of the Greater Manchester Police area (and a rough, tough beat by any standards).

However, she’s also facing a domestic crisis as her mother, Cora, normally a law-abiding citizen, is increasingly looking back to her wild youth, contemplating a possible reunion with her old flame, and Lucy’s estranged father, gangland boss Frank McCracken. As you can imagine, this isn’t going down too well with Lucy, who, when she first discovered that she and McCracken were related – and it was as much a revelation to him as to her – made a deal with him to keep it secret, because if news like this got out, it could be mutually catastrophic to both their careers.

However, she’s also facing a domestic crisis as her mother, Cora, normally a law-abiding citizen, is increasingly looking back to her wild youth, contemplating a possible reunion with her old flame, and Lucy’s estranged father, gangland boss Frank McCracken. As you can imagine, this isn’t going down too well with Lucy, who, when she first discovered that she and McCracken were related – and it was as much a revelation to him as to her – made a deal with him to keep it secret, because if news like this got out, it could be mutually catastrophic to both their careers. At the same time, there are various heinous things going on in Crowley, which are soon likely to distract Lucy even from this. A number of pets have disappeared in unusual circumstances, and Lucy traces this, or so she thinks, to a dog-fighting ring, only to then learn that she’s off-track – and that now people are disappearing as well.

At first, it’s members of the homeless community, whose absence no one has noticed except Sister Cassiopeia, a drug-addicted former nun, who caters to the Skid Row folk as a kind of self-appointed pastor. Lucy initially takes this story no more seriously than she does the urban myth that a mysterious black van was prowling the housing estates on the nights the pet dogs were abducted … until she learns that this black van is supposedly still on the prowl, and no longer just looking for animals.

Something fiendish is clearly going on. It may be connected to the horrific inner-city wilderness that is the Fairview Landfill site, because weirds things are also supposedly going on out there. But alternatively, it might be linked to the network of disused air-raid tunnels that run underneath Crowley’s many derelict mills. One thing is certain: when an OAP is brutally abducted from his home – and once again there are stories that a van was heard racing away – Lucy has no option but to launch herself into a very complex and distressing investigation.

As I say, STOLEN is out today, from all the usual retailers.

The worst mob hits ever

I saw a rather concerning headline in the news this last week. It read:

Organised crime in the UK is bigger than ever before

The accompanying story described how Britain has now become the hub of numerous international criminal networks, whose various rackets include prostitution, protection, slave-trading, gun and drug smuggling, murder-for-hire and the laundering of billions of pounds through London every year. Other figures, apparently straight from the National Crime Agency, reveal that there are 4,629 active gangs and syndicates in the UK today, which together employ 33,598 full-time professional criminals.

Stats like these will come as a sobering shock to many, particularly to those one or two reviewers of my Lucy Clayburn novels who have expressed doubt that highly-organised and well-resourced criminal cartels like the Crew – my fictional firm who control the North of England – genuinely exist in Britain today.

I should say straight away that I’m not quoting these sad figures as some kind of ‘told you so’ point-scoring exercise. I mention them simply to illustrate that the terrifying influence and extreme brutality exercised by the Crew in my three Lucy Clayburn novels to date –

STRANGERS

,

SHADOWS

and

STOLEN

– are not too far removed from reality.

I should say straight away that I’m not quoting these sad figures as some kind of ‘told you so’ point-scoring exercise. I mention them simply to illustrate that the terrifying influence and extreme brutality exercised by the Crew in my three Lucy Clayburn novels to date –

STRANGERS

,

SHADOWS

and

STOLEN

– are not too far removed from reality. The latest of those three novels, the one published today in fact,

STOLEN

, is particularly worth mentioning in this context because it features what has been described as ‘a horrendous sequence’ in which a major gang hit is carried out with ‘visceral, shocking violence’.

The latest of those three novels, the one published today in fact,

STOLEN