Can evil cascade through the generations?

Big news today as I’m exclusively able to unveil the cover to my next Lucy Clayburn novel, STOLEN.

Big news today as I’m exclusively able to unveil the cover to my next Lucy Clayburn novel, STOLEN.Here it is, alongside. Hope you approve. It’s certainly eye-catching, I’m sure you’ll agree.

I’ll talk a little bit more about that in a minute, but in addition this week, I thought it would be interesting to take a trip down memory lane and check out 10 of the worst serial killers in distant history – you know, that long-ago period of time when serial killers weren’t supposed to exist? I’m hoping you’ll find that section of today’s blog informative if not exactly fun. And in keeping with that subject, this week’s book review is an intriguing one indeed.

I’ll be focussing on THE WEREWOLF OF BAMBERG by German author, Oliver Potzsch. Despite sounding like a horror novel, this is actually an intense period crime-thriller. As always, you’ll find that detailed review towards the lower end of today’s blogpost. You can jump straight down to it if you wish, or alternatively you can hang around for those other things I promised to mention.

STOLEN

, the third outing in the Lucy Clayburn series, due for publication on May 16, takes my young Manchester policewoman into slightly different territory from the norm.

STOLEN

, the third outing in the Lucy Clayburn series, due for publication on May 16, takes my young Manchester policewoman into slightly different territory from the norm. In

STRANGERS

, she went undercover as a prostitute to try an apprehend a streetwalker who was sexually murdering her male clients, and in

SHADOWS

she was a part of the team pursuing the so-called Red Headed League, a gang of ultra-violent armed robbers who were preying on the city’s gangsters.

In

STRANGERS

, she went undercover as a prostitute to try an apprehend a streetwalker who was sexually murdering her male clients, and in

SHADOWS

she was a part of the team pursuing the so-called Red Headed League, a gang of ultra-violent armed robbers who were preying on the city’s gangsters.In STOLEN , it’s different again, Lucy getting involved in a baffling and distressing case when a bunch of OAPs and vagrants start dropping out of sight one by one. Again, it feels as if a killer is on the loose, but the eventual truth will be infinitely more terrifying even than that.

For fans of the Lucy Clayburn series, I can assure you there will be much of the usual: genuine Brit-Grit as she wends her way around the trash-strewn Manchester backstreets, dealing with lowlifes of every sort, clashing constantly and ever more aggressively with the city’s contingent of career criminals, and at the same time, though she rides a Ducati motorbike and mingles with toughs, using brain rather than brawn in her efforts to solve a perplexing mystery.

I think I can safely add that there are one or two traditional(ish) horror elements in this book too. It’s NOT a horror novel, of course – it’s firmly a crime-thriller. But one subtext we’ll be looking at is the way evil, if it goes unchecked, can cascade down the ages and through the generations like a virus. We’ve also got some very gruesome deaths – some of the worst I’ve ever committed to paper, I think – and a few decayed, post-industrial settings that wouldn’t be out of place in the dark neo-Gothic world of the Universal Frankenstein films of the 1930s.

Okay, that’s enough for now. As I say, STOLEN can be purchased from May 16 from all the usual outlets, but it’s available for pre-order right now.

And now that other little thing I was talking about …

Slaying since time immemorial

There is a popular misconception that serial killers only commenced their war against mankind from the late 19th century, from roughly around the time of Jack the Ripper, whereas during all the ages before then we’d been spared this bizarre and terrible form of deviancy.

Unfortunately, the truth is grimmer.

Jack the Ripper, though he laid down a bloodstained template, wasn’t even London’s first serial killer, let alone the world’s. All the way back through the 19th century and into the 18th, the annals of crime repeatedly report the escapades of criminals who killed, raped and tortured repeatedly. But at a time when policing was sparse and disorganised, and communications across counties (never mind across whole countries) poor to nonexistent, it’s perhaps no surprise that these terrifying stories did not become the national cause célèbres that they are today. And that is even more the case if you delve deeper into antiquity.

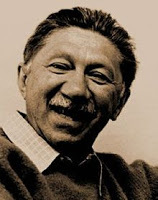

It’s entirely possible that before industrialisation, in an age primarily of agriculture, there was less day-to-day violent crime simply because populations were more dispersed and family units stronger. Famed psychologist, Abraham Maslow (left) conjectured that rape and murder in particular were crimes that flourished in overcrowded slums, where people were forced to live on top of each other and had nothing else in their lives but work, drudgery and alcohol. But whereas that rule might have applied generally, in truth you don’t need to gaze too penetratingly back into the distant mists of time to discover that there were still some individuals who were equally as vicious, cruel and deranged as the worst of our modern-day serial murderers.

It’s entirely possible that before industrialisation, in an age primarily of agriculture, there was less day-to-day violent crime simply because populations were more dispersed and family units stronger. Famed psychologist, Abraham Maslow (left) conjectured that rape and murder in particular were crimes that flourished in overcrowded slums, where people were forced to live on top of each other and had nothing else in their lives but work, drudgery and alcohol. But whereas that rule might have applied generally, in truth you don’t need to gaze too penetratingly back into the distant mists of time to discover that there were still some individuals who were equally as vicious, cruel and deranged as the worst of our modern-day serial murderers.Many of them, of course, are what we would classify today as despots:

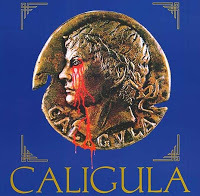

The likes of Nero (37-68 AD), Caligula (12-41 AD), Commodus (161-192 AD) and Caracalla (188-217 AD), perhaps the four most notoriously unhinged Roman emperors, or all-conquering, all-slaughtering warlords like Attila (406-453 AD) and Ghengis Khan (1162-1227), or rulers who simply defined themselves by their casual but ruthless brutality: Vlad the Impaler (1428-1477), Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584), Bloody Mary of England (1515-1558).

The likes of Nero (37-68 AD), Caligula (12-41 AD), Commodus (161-192 AD) and Caracalla (188-217 AD), perhaps the four most notoriously unhinged Roman emperors, or all-conquering, all-slaughtering warlords like Attila (406-453 AD) and Ghengis Khan (1162-1227), or rulers who simply defined themselves by their casual but ruthless brutality: Vlad the Impaler (1428-1477), Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584), Bloody Mary of England (1515-1558).The simple explanation behind these icons of evil could be that they are yet further examples of humanity’s folly when it comes to appointing leaders who are completely unsuited to the task – even in recent times it is clearly the case that people hold power who patently shouldn’t – while the rest of society got on swimmingly because they were all downtrodden together. But these warped individuals undoubtedly tick many of the serial killer boxes: rampant narcissism, sexual sadism, casual cruelty, consciences that were either inert or completely absent. And anyway, you don’t have to look very much farther into the lower orders of these same time-periods to discover that there were other heinous villains on the loose too, and this lot you might have missed at first glance because they were humbler creatures and therefore not as newsworthy (especially in an age when there was no news-wire at all).

At the end of the day, don’t worry about it. You won’t have to go leafing through the dusty chronicles yourselves, because I’ve done it for you. Today, as promised, I’m going to showcase 10 little-known cases of serial murder from distant history.

Before I proceed there are one or two that most of us – certainly those of us who are horror fans – will already be familiar with. Gilles de Rais (1405-1440), Elizabeth Bathory (1560-1614, pictured right, Hammer-style, aka Ingrid Pitt) and Sawney Bean (16th century – if he existed at all!) are infamous the world over and would figure in any list of mankind’s worst killers even by modern standards, so I’m purposefully going to leave those three out.

Before I proceed there are one or two that most of us – certainly those of us who are horror fans – will already be familiar with. Gilles de Rais (1405-1440), Elizabeth Bathory (1560-1614, pictured right, Hammer-style, aka Ingrid Pitt) and Sawney Bean (16th century – if he existed at all!) are infamous the world over and would figure in any list of mankind’s worst killers even by modern standards, so I’m purposefully going to leave those three out.The focus today, in chronological order, is those human predators of ancient antiquity who remain largely unknown:

Locusta

A bit of a cheat in this first instance, as Locusta was an expert poisoner and professional assassin rather than a serial killer per se, but one can’t help wondering how she’d ever have acquired such a macabre skillset if she hadn’t been very interested (and experienced) in it from the outset. All we really know about her is that she came to Rome from Gaul in the early 50s AD, already an accomplished poisoner, and that she rapidly began hiring herself out to high-paying clients, carrying out an unspecified number of successful murders.

Somehow detected and imprisoned, she saved herself by providing effectively destructive potions to some of the city’s more ruthless celebrities, such as Agrippina the Younger, and later on, her son, Emperor Nero, who was so impressed with the results that he pardoned her, paid her handsomely and appointed her head-tutor at a special school for poisoners. Locusta came unstuck when Nero committed suicide in 68 AD. She was arrested again by the Emperor Galba, who paraded her as a typical example of his forerunner’s amoral degeneracy, and this time was executed after first been led through the streets of Rome in chains and mocked and stoned by the populace.

Gilles Garnier

Gilles GarnierClassic example of a serial killer whose depredations were so horrifying to the community he terrorised that it soon came to believe a monster was in its midst, specifically a werewolf. Known as the ‘Wolf of St Bonnot’, Garnier lived in Dole in the Franche-Comte Province of France in the 1570s. A married man, but already a reclusive outsider with a bad reputation, it might have been inevitable that Garnier would become a suspect when, in 1572, a series of murders of local village children began. But Garnier brought the full force of the law down on himself the following year when he was found in possession of one of the bodies.

The murders had been spectacularly gruesome, five infants strangled and then mutilated, meat torn from their bones presumably for the purpose of cannibalism. It perhaps isn’t difficult to see why a primitive rural community felt they were in the grip of a man-wolf, and when Garnier confessed as much, saying that a magical ointment had enabled his transformation, the case was deemed complete. He was duly convicted and burned at the stake. Historians now consider him an archetypal serial killer, probably driven to his crimes by a combination of lust and hunger.

Peter NiersWhether Niers was guilty of all 544 of the brutal murders he was eventually convicted for, it’s clear that he was involved in violent crime as a profession, and that he relentlessly robbed and killed across a wide area of southern Germany in the 1570s, one of a network of bandits plaguing the remoter, more thickly forested regions.

He also seems to have been fairly well-known. Other captured highwaymen named him as an accomplice in numerous horrible offences, including the murder and rape of young women in darkened backstreets as well as the more mundane murder-for-profit of travellers on lonely roads. Niers himself, held in the late 1570s in Gersbach, confessed to 75 such slayings, but after escaping, even that massive body-count appears to have grown exponentially, with pamphlets and ballads carrying tales that Niers had now made a pact with the Devil, and as such, had become an evil sorcerer who frequently sacrificed unborn babies that he’d cut from the wombs of their still-living mothers. Such infamy was his ultimate undoing.

On his capture in 1581 (having been recognised in a bathhouse in Neumarkt), he was tortured, confessed, and later executed by being flayed, roasted, broken on the wheel and quartered.

On his capture in 1581 (having been recognised in a bathhouse in Neumarkt), he was tortured, confessed, and later executed by being flayed, roasted, broken on the wheel and quartered.Christman GenipperteingaDespite the casting of Peter Niers as a kind of 16th century Public Enemy No. 1, another felon operating in much the same area at much the same time, appears to have run up an even more incredible tally of victims. German bandit, Christman Genipperteinga supposedly murdered 964 people during a reign of terror lasting from 1568 until 1581.

On the face of it, this number appears to be so preposterous that it’s led some scholars to wonder whether Genipperteinga ever existed at all and to question if he’s in fact a composite of a number of violent criminals who were on the loose in southern Germany at the same time. That said, when there was almost no organised law-enforcement with which to combat widespread banditry, and in a land of extensive wilderness, it’s not impossible that such an individual could have prospered.

Genipperteinga mainly attacked travellers from a clifftop stronghold in the Bernkastel-Kues district, but he also murdered accomplices, poisoning them and dumping their corpses down mine shafts, and after kidnapping a young girl, fathered six children by her, strangling them all. Finally arrested in 1581, he was broken on the wheel, and left lingering on the gibbet alive for nine days.

Genipperteinga mainly attacked travellers from a clifftop stronghold in the Bernkastel-Kues district, but he also murdered accomplices, poisoning them and dumping their corpses down mine shafts, and after kidnapping a young girl, fathered six children by her, strangling them all. Finally arrested in 1581, he was broken on the wheel, and left lingering on the gibbet alive for nine days. Peter StumppBest known of this bunch of deviants, Peter Stumpp – more famous as the ‘Werewolf of Bedbourg’ – was yet another German serial slayer of the 16th century, but his particular case raises several questions. Why did so many sadistic mass-killers infest Germany at this time? And just how credulous were the local courts?

Peter StumppBest known of this bunch of deviants, Peter Stumpp – more famous as the ‘Werewolf of Bedbourg’ – was yet another German serial slayer of the 16th century, but his particular case raises several questions. Why did so many sadistic mass-killers infest Germany at this time? And just how credulous were the local courts?Stumpp was a farmer in the Bedbourg district of Cologne, whose crimes during the 1580s were so ghoulish that for years afterwards it was considered a certainty he’d been a werewolf. But did the local authorities really believe that, or were they just going along with mass hysteria so as not to look complacent?

One modern theory is that a succession of harsh winters prior to this had damaged crops, causing famine and lawlessness; that might have explained the preponderance of vicious criminals. In addition, the Electorate of Cologne was embroiled in sectarian warfare throughout the 1580s, meaning that heresies were rife and that atrocities often went unpunished, so the few offenders brought to trial had to be made examples of; declaring them werewolves and making them pay the ultimate horrendous price was a lesson that would have been lost on no one.

Stumpp certainly assisted with this. Arrested in 1589, he admitted to having killed and butchered 14 children (including his own son) and two women during a lifetime of devil-worship. He also claimed to have met Satan, who’d given him a wolf-belt that turned him into a beast.

In reward for his crimes, he was broken on the wheel and then burned in the same fire as two convicted accomplices, his wife and daughter.

Björn PéturssonIceland’s only known serial killer to date, Björn Pétursson’s life reads like a horror novel, and yet much of it is testified to in reliable court documents. The nastiness started early, his mother having developed a craving for blood while pregnant with him, and his oddball father agreeing to let her drink his.

After this, born into a bleak corner of the Icelandic interior in 1555, Pétursson led as conventional a peasant childhood as possible (despite showing some violent tendencies), but at the age of 15 had a bizarre dream in which a stranger told him to climb a local mountain, on top of which he’d locate the implement that would make his name. The next day, Pétursson climbed the peak and found the axe with which he would go on to kill his first victim, a neighbouring farm-boy chosen at random. Though it was only after he’d inherited a nearby croft that he gave full rein to his blood-lust, slaughtering all visitors and passers-by with the same trusty blade. In 1596, when a homeless woman escaped his clutches (after he’d already slain her three children), he was arrested.

The remnants of many corpses – one estimate is 18 – were found on the premises, and Pétursson was convicted and subsequently became another to die bloodily on the breaking-wheel.

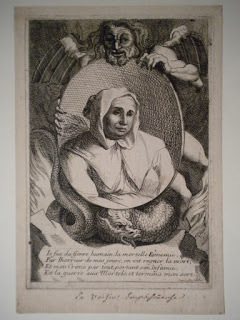

La VoisinParis in the 17th century was a hotbed of crime and vice, much of it interwoven with witchcraft, and one of the queens of this cesspit was Catherine Montvoisin, aka ‘La Voisin’.

La VoisinParis in the 17th century was a hotbed of crime and vice, much of it interwoven with witchcraft, and one of the queens of this cesspit was Catherine Montvoisin, aka ‘La Voisin’.A key problem with the 21st century conviction that witchcraft trials were all nonsense and the alleged perpetrators invariably innocent is that it doesn’t allow for the widespread belief in witches at the time, which was one good reason why considerable numbers of cunning individuals behaved as if they were witches in order to make money. La Voisin was probably the best example we have, an habitual drunk but also the organiser of an all-female network of abortionists, midwives and fortune-tellers who slowly graduated to casting spells, holding Black Masses (involving draining blood from aborted foetuses, but sometimes from live babies too), and, to make it look as if their hexes worked, administering lethal substances (using such horrific methods as serving deadly elixirs and rubbing arsenic into syphilis sores).

Estimated to have killed almost 2,500 victims, La Voison was arrested in 1679, when Louis XIV’s secret police moved in. Her belief that, having worked for highly-placed Parisians, she’d be protected, came to nothing. She was burned at the stake in 1680.

Estimated to have killed almost 2,500 victims, La Voison was arrested in 1679, when Louis XIV’s secret police moved in. Her belief that, having worked for highly-placed Parisians, she’d be protected, came to nothing. She was burned at the stake in 1680.Beast of GévaudanA seminal case for all kinds of reasons, not least because it established several tenets of werewolf lore, namely that all the best cases were to be found in France, and that it would require silver bullets to dispatch them. For our subject today - historical serial killers - the Beast of Gévaudan isn’t as tenuously connected as some may think, because serial murder is one of very few possible explanations for the mystery that occurred there.

In short, between 1764 and 1767, a 90-kilometre region of south-central France was the scene of a murderous rampage, which claimed 113 deaths, some of the victims partially eaten, all with their throats torn.

It was a made-to-measure werewolf case, except that this was the Age of Enlightenment, and no one believed in werewolves anymore. Despite this, witnesses claimed to have seen a wolf-like creature, and when the carnage ended, a hunter called Jean Chastel having shot the beast with a silver bullet, the carcass was that of a large but unknown species of wolf.

It was a made-to-measure werewolf case, except that this was the Age of Enlightenment, and no one believed in werewolves anymore. Despite this, witnesses claimed to have seen a wolf-like creature, and when the carnage ended, a hunter called Jean Chastel having shot the beast with a silver bullet, the carcass was that of a large but unknown species of wolf.The Chastel incident is now dismissed by certain modern commentators, who have decided that no single wolf could have been responsible for such carnage and now suspect that an unknown human agency was attacking villagers with a trained animal (possibly a lion), a theory examined in the 2001 movie, (Brotherhood of the Wolf).

Lewis HutchinsonIn another case that could easily become the subject of a Gothic horror film, Scottish immigrant Lewis Hutchinson arrived in Jamaica in the 1760s, claiming to be a doctor, though his real past was unknown. The first thing he did was purchase a ruined plantation house, which he restored and named Edinburgh Castle.

Up to this point, he’d behaved legally, however suspicions soon grew that many of the cattle he started raising there were stolen. If that was his worst offence, he might have been tolerated, but then travellers started disappearing in the vicinity. Initially, no one knew that Hutchinson was using them for target practise, literally waylaying them with gun in hand and hunting them down like animals, killing them for sport. Afterwards, he would pocket whatever wealth they’d been carrying, and his slaves would butcher the corpses, disposing of the fragments in a nearby sinkhole.

The longer Hutchinson remained at liberty, the more reckless he became, murdering invited dinner guests and letting stories spread that he held obscene orgies at the Castle. But after shooting dead a British soldier who was trying to arrest him, he tried to flee Jamaica, only to be arrested by the Royal Navy, and hanged in 1773. Excavation of his estate later uncovered a total of 43 corpses.

Darya Nikolayevna SaltykovaIn times gone by, the easiest way for a sadistic murderer to act out his/her violent fantasies and yet limit the chances of lawful retribution was for the victims to be selected from the lower classes, especially if they were indentured to the killer as servants or slaves.

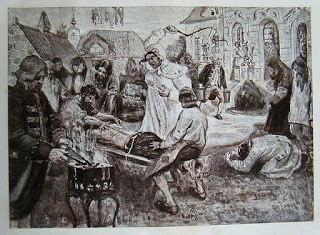

Darya Nikolayevna SaltykovaIn times gone by, the easiest way for a sadistic murderer to act out his/her violent fantasies and yet limit the chances of lawful retribution was for the victims to be selected from the lower classes, especially if they were indentured to the killer as servants or slaves.Obviously, this confined said advantage to the controlling hierarchy, but even then there are a remarkable number of cases that did come to court, and in several of them the perpetrator was female.

We’ve already spoken about Elizabeth Bathory (650 victims). We could just as easily discuss Countess Catalina de los Ríos y Lisperguer in 17th century Chile (40 victims), and Delphine LaLaurie in New Orleans in the late 18th century (tally unknown).

It’s still the case that more male landowners were likely responsible for these kinds of crimes than female, but the female cases tended to shock more, certainly at the time, which might explain their lasting infamy. One lesser-known example was that of wealthy Moscow socialite Darya Nikolayevna Saltykova, who in 1762 was arrested for personally whipping to death 138 of her female servants. Her aristocratic status had protected her up until the accession of Catherine the Great, but the new tsarina acted swiftly because she wanted to make visible concessions to the serfs.

Even then, Saltykova was spared the noose, and imprisoned in an underground dungeon, where she died in 1801.

***

At times like this, I can’t help wondering if many of our most monstrous myths derive from the murderous activities of demented human beings like these.

We can see here that in an age before the science of psychology and the study of mental illness, when there was no real comprehension of aberrant sexual desire particularly if it was mingled with violence, a non-human explanation was regularly leaped upon. Modern-day forensic profilers have even identified weird sexual elements in the activities of prolific poisoners despite their having next to no physical contact with their victims. But though poisoning was better understood in the old world than lust-murder – mainly because it was the chief means by which the low could bring down the high – to poison someone was still held to be so wicked that once again concerns about witchcraft and devilry often went hand-in-hand with it.

But just consider the vast numbers of myths our ancestors lived in fear of, wherein terrifying, unstoppable predators lurked just beyond the edges of human society.

But just consider the vast numbers of myths our ancestors lived in fear of, wherein terrifying, unstoppable predators lurked just beyond the edges of human society.It’s not just werewolves, but vampires, ogres, trolls. In the poem Beowulf, Grendel (left) was a blueprint serial killer. In Jack the Giant Killer, Cormoran raided Cornish farming communities, taking lives and livestock at will. What about the Ango-Saxon ‘sceaudagenga’ (or shadow-man), who lurked deep in the forest, and if you met him, you’d never be coming home?

Even foul figures of of classical mythology, like the Minotaur and Medusa (left), possessed recognisably human characteristics, despite the horrors they wreaked. When you think how many monsters of this type were believed to inhabit the fringes of the Ancient World, to the terror of isolated, ignorant communities, you can’t help wondering if, in truth, an exceptional number of serial killers were hard at work.

Even foul figures of of classical mythology, like the Minotaur and Medusa (left), possessed recognisably human characteristics, despite the horrors they wreaked. When you think how many monsters of this type were believed to inhabit the fringes of the Ancient World, to the terror of isolated, ignorant communities, you can’t help wondering if, in truth, an exceptional number of serial killers were hard at work. Perhaps the only difference between then and now is that these days we can put names and faces to the monsters – eventually. Not that it makes us any the less afraid of them.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE WEREWOLF OF BAMBERG

THE WEREWOLF OF BAMBERG by Oliver Potzsch (2015)

It’s the 1660s, and Schongau hangman, Jakob Kuisl, and his family arrive at the forest-begirt town of Bamberg, Bavaria, to celebrate the wedding of his estranged brother (and local hangman), Bartholomaus. A happy event is in prospect, Jakob’s beautiful and spirited daughter, Magdalena, hoping that her father and uncle will at last make friends and put behind them the mysterious event that split their family apart during their youth.

But all is not well in Bamberg. A series of ghastly murders is in progress, the unknown assailant horribly mangling the victims and scattering their dismembered body-parts. It hasn’t taken long for rumours to spread that a werewolf is on the prowl, though Jakob and Magdalena – a father-and-daughter crime-fighting team (there have been four ‘Hangman’s Daughter’ books before this one) – come to dispute this, noting that most of the gory fragments were severed from the original bodies cleanly rather than torn with tooth and claw.

A werewolf with a blade? It seems unlikely.

Even more suspiciously, some of the victims, the vast majority of whom are drawn from the town’s patrician class, show marks of the rack and branding-iron.

A werewolf who abducts and tortures his victims before tearing them apart? It seems even more unlikely. But Bamberg is not a town where rhyme and reason exist in abundance. Still haunted by the events of forty years earlier, when a far-reaching witch trial saw hundreds of citizens, most of them innocent, tortured and then burned at the stake, fear and superstition are rife in the flea-infested hovels and narrow, stone-arched streets. The townsfolk aren’t even sure what form their adversary takes: is it a man/wolf hybrid, a warlock who can turn himself into an actual wolf; or a maniac wearing a pelt? – whichever the case, they are certain it’s a creature of the Devil, and that it must be destroyed, along with all its spawn.

Jakob undertakes to investigate the crimes, aided very efficiently by Magdalena, her educated husband, Simon, and his close friend and local physician, Master Samuel. But the situation worsens when Sebastian Harsee, suffragan bishop of Bamberg, sees advantage in stirring up these fears because if terror of the darkness brings the townsfolk closer to God, it can only empower his own position. Further complications then arise when a dangerous hunting dog gets loose outside the city (and this predator does leave his victims mauled and ripped), by an outbreak of rabies (an illness misunderstand by the medical science of the time, and the sufferers of which snarl and froth at the mouth), and by the escape from the prince-bishop’s menagerie of a baboon (a completely alien creature to most Germans of this era).

As the attacks continue, hysteria increases, and accusations fly everywhere. Meanwhile, Jakob and Magdalena find themselves with many suspects to consider. The hideously scarred Jeremias, custodian of a local tavern, is a friendly enough soul, so much so that Magdalena will happily leave her two children in his care, but increasingly, it seems, he has odd and ghoulish interests, and his past is another one that is shrouded in mystery. Aloysius, a solitary individual, both looks and smells like the hunting dogs he tends; he is an odious individual, whom Jakob instinctively dislikes. Then there is Bartholomaus, Jakob’s own brother. The deep enmity between these two partly stems from the fact that, when they were boys, Jakob never wanted to follow their father into the hangman trade, while Bartholomaus, a keen student of the most brutal forms of punishment, positively looked forward to it.

The case finally turns deadly for the Kuisl family themselves, when Barbara, Magdalena’s younger sister, falls for handsome young actor, Matheo, who is part of a travelling troupe visiting the town, only to see him clapped in irons as a suspect. In this case, the evidence is actually rather good. Items associated with black magic are found among the actors’ possessions, along with a number of wolf-skins. Also suspected, Barbara goes into hiding in company with the troupe’s depressed resident-writer, Markus Salter – as much from the baying mobs rampant in the city as from the actual authorities – but it’s clearly only a matter of time before she’ll be found. If Jakob wants to save his daughter from a terrible death, he knows he must crack the case very quickly indeed …

I’d never encountered the Hangman’s Daughter stories before, so it probably wasn’t ideal to come in at volume five. It didn’t spoil my enjoyment of The Werewolf of Bamberg , but I must say – this is one of the strangest novels I’ve ever read.

First of all, it’s an excellent recreation of a turbulent age, a time when the brutality and mysticism of the Middle Ages is slowly and reluctantly giving way to the Enlightenment, but an era when Western Europe is still the epitome of the Third World. Real skills of any sort, unless they are connected to violence and death, are in short supply. Education is thin on the ground. Personal wealth is something to be defended at all costs, but life in general is cheap. Most crimes, even petty ones, are punishable by death or at least a severe whipping. Trials might hinge on the reputation of the accused rather than factual evidence. Some occupations are held to be vastly less honourable than others, including, amazingly, the medical profession. Despite it being an age of faith, basic moralities are skewed, community leaders, including senior churchmen, setting a very poor example with their many and varied vices.

This attention to authentic historical detail is fascinating, invoking a different and distinctly non-chocolate box picture of the near-distant past. I was utterly absorbed in it – much more so, sadly, than I was by the actual mystery.

Oliver Potzsch does an impressive job of setting up a whole range of suspects, while the essential back-story – a political stitch-up of epic proportions – is effectively drizzled through the narrative rather than thrown at us in one lump of exposition, but the pace at times is wearisome. This may partly be down to losses in translation, though I’m not sure it is. Lee Chadeayne does a sterling job of bringing The Werewolf of Bamberg from German to English, leaving us with a very readable text, but there is an awful lot of repetition here, and that must be part of the original writing. I soon got tired of seeing Jakob and Bartholomaus quarrelling over nothing or hearing that the occupation of executioner is badly thought-of (and why would that surprise or outrage anyone?). As such, the novel overall is perhaps twice as long as it needs to be.

In addition, it’s a personal belief of mine that too many characters can get in the way. Jakob and Magdalena are the stars of the book, or they would be if their contributions weren’t obscured by what amounts to an ensemble cast, all of whom jockey for prominence; in fact, so many are the named personages in this book that at times it’s a real challenge keeping up with everyone and remembering what they are doing.

My other main complaint is about Jakob Kuisl himself. I like him as a character – a gruff, middle-aged man who doesn’t look after himself is a rare delight in hero terms – but find it difficult buying into the conceit that, though he’s a long-serving hangman, he feels sorrow for his victims and often acts to reduce their pain. Wouldn’t he get sacked for doing that, or maybe worse? What’s more, when this approach fails, he consoles himself with the knowledge that he’s merely a cog in an unjust machine and that it’s never his personal fault. All very well, but when you consider that his duty has seen him not just string felons to the gallows, but burn them at the stake, break them on the wheel and draw and quarter them between teams of horses, his oft-expressed disgust at those other executioners, his brother for example, who are consciously vicious, rings a bit hollow to modern ears.

But all that said, I stuck with it to the end. So, while I wouldn’t call The Werewolf of Bamberg a real page-turner, its atmosphere and tone did more than catch my interest. In addition to the historical angle, I’ve long been a sucker for werewolf stories, and even though it becomes apparent early on that we’re not dealing with a werewolf here, but a serial killer, it is clearly based on the real-life mystery of the Werewolf of Bedburg, and we still find ourselves on dark, winding streets with a horrific menace stalking us through the shadows. In that regard, it’s as effective a horror story as it is a thriller and having a foot in both these camps is not always a bad thing.

I recommend it to all dark fiction fans, but at more than 600 pages you’ll need plenty time in which to read it.

As usual – purely for the fun of it – here are my picks for who should play the leads if The Werewolf of Bamberg is ever adapted for English-language film or TV (but I still think the main concept would be a tough sell for a modern audience):

Jakob Kuisl – Liam NeesonMagdalena Fronwieser – Cosma Shiva HagenBartholomaus Kuisl – Danny WebbSimon Fronwieser – Martin FreemanMaster Samuel – Oded FehrJeremias – Rutger HauerSebastian Harsee – Gary OldmanMarkus Salter – Iwan Rheon

(We’ve used a lot of pictures today, including several original, rather grotesque woodcuts, but also a magnificent shot of Inner Iceland by Albert Dros, and a startling werewolf pic which I found floating around online and will be happy to give a credit for if anyone knows who the creator is. The same applies for the image of Medusa, while the image-grab of Grendel comes from the 2007 movie, Beowulf).

Published on February 20, 2019 04:02

No comments have been added yet.