Paul Finch's Blog, page 5

May 5, 2022

Big fun in prospect as festival season starts

Well, Easter is past and spring is well and truly underway. Hope it’s looking promising for everyone so far (international calamities aside, of course). All I can say is thank Heaven the festival and convention season is almost upon us. Today’s blog therefore, is all about that.

I’ll be telling you where I am as the big events unfold, what I’ll be doing and who I’ll be doing it with. I’ll also be reporting on the current status of my new novel, NEVER SEEN AGAIN, which seems to be going down well (and is currently ONLY 99p on Kindle).

In addition, and because my festival schedule, as usual, winds its way across the darker end of the literary spectrum, focussing mainly on crime, thriller and horror fiction, I thought that for today’s review I ought to find a novel that perhaps has a foot in every one of those camps. As such, I settled on Ian McGuire’s extremely dark and chilling THE NORTH WATER.

It’s the sort of novel you might sometimes find on the literary fiction shelf and maybe, for that reason, ignore it. If that’s the case, don’t ignore today’s review. You’ll find it, as usual, in the Thrillers, Chillers section in the lower end of this blogpost. Seriously, no fan of dark fiction can afford to pass this novel by.

Of course, if you’re only here for the Ian McGuire review, that’s absolutely fine. Zoom on down to it straight away. Before then though, you might be interested in …

Let the conventions commence

The literary festival season is one of the joys of the writing life. Literary events, as I like to think of them, can be held at any time and in almost any place, though for the most part they tend to come thicker and faster from mid spring through to late autumn, the majority tending to congregate in the warmest months of the year, which only adds to the holiday atmosphere that often surrounds them.

I’m leery of getting too excited about this year’s agenda, primarily because I don’t want to tempt fate. In 2020 of course, it was all but cancelled due to the Covid pandemic, while last year, with the virus still around, it was really only a shadow of its normal self. This year, thus far, we have what promises to be a full programme, though of course you can’t be too confident.

I’m leery of getting too excited about this year’s agenda, primarily because I don’t want to tempt fate. In 2020 of course, it was all but cancelled due to the Covid pandemic, while last year, with the virus still around, it was really only a shadow of its normal self. This year, thus far, we have what promises to be a full programme, though of course you can’t be too confident. But if this year’s schedule actually comes to pass, and fingers crossed it will, it promises an awful lot. And I hope to be participating as fully as everyone else.

For the uninitiated, these events, which mostly tend to be held over carefully selected weekends, at specific venues – usually hotels in city centres where there is lots of immediate access to pubs, Indian restaurants and kebab shops – while not exactly centred around book-talk, usually have lots of book stuff going on because they are attended primarily by writers and readers. Invariably, there are panels, workshops, readings from new books, ‘pitch an agent’ sessions, quizzes and the like. Plus, there is almost always a Book Room, where all kinds of new releases, overseas imports and independent publications that you’re unlikely to have read about in the trade press can be had at reasonable prices.

Of course, the centre of all activity tends to be a bar, where the atmosphere ranges from genial to raucous (and everywhere in between) … but never underestimate the importance of this. The whole idea of these events is to bring authors into direct contact with their public. And when I say authors, I mean big names, major international sellers, wordsmiths who you can guarantee would sell the film rights to their laundry list if they actually have one. So, if you’re there, even if you’re just a reader or a fan, you shouldn’t be afraid to doorstop these guys and gals as they hold up the bar or wander the hotel corridors, and chat to them. Because that’s why they’re there. They attend these events specifically to socialise with those who read and enjoy their work.

Of course, the centre of all activity tends to be a bar, where the atmosphere ranges from genial to raucous (and everywhere in between) … but never underestimate the importance of this. The whole idea of these events is to bring authors into direct contact with their public. And when I say authors, I mean big names, major international sellers, wordsmiths who you can guarantee would sell the film rights to their laundry list if they actually have one. So, if you’re there, even if you’re just a reader or a fan, you shouldn’t be afraid to doorstop these guys and gals as they hold up the bar or wander the hotel corridors, and chat to them. Because that’s why they’re there. They attend these events specifically to socialise with those who read and enjoy their work. As I say, these are special occasions. So, if you’ve never popped onto this circuit, even for a day or so, you’re missing a treat.

My schedule

My own involvement this year will, perhaps inevitably, be based around my 2022 publication, NEVER SEEN AGAIN .

For those unaware (and if you exist, shame on you), it’s an urban thriller built around a cold case kidnapping, and featuring a disgraced investigative reporter who, when he unexpectedly receives a vital clue, goes all out to discover what happened to an heiress abducted over six years earlier, and who might – though it seems incredible – still be alive.

For those unaware (and if you exist, shame on you), it’s an urban thriller built around a cold case kidnapping, and featuring a disgraced investigative reporter who, when he unexpectedly receives a vital clue, goes all out to discover what happened to an heiress abducted over six years earlier, and who might – though it seems incredible – still be alive. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not going to be attending these functions purely to hawk my latest novel around. That would be a tad unsavoury. But there’ll be plenty copies at most of them, and I’ll be there, with pen in hand, so, you know …

Anyway, the events worth mentioning (thus far, because others may join the list as the weeks roll by), in chronological order, are:

CRIMEFEST, Bristol, May 12-15

One of the major crime-fiction events in the calendar, often one of the earliest in the year and always (to date, at least) held in the grand old city of Bristol. This year, the host venue is the Mercure Bristol Royal.

This is another of my favourite weekends of the year, because the atmosphere is always superb but also very literary. In my experience, this one tends to be colonised by writers, agents, editors and publishers rather than readers, though readers are welcome to attend, and quite a few do. There is often much industry chat, but plenty amber nectar goes down too … it’s a great social occasion, and located right in the heart of one of the most interesting cities in Britain.

I’ll be there, as I say, and am fortunate enough to be participating on a panel on the Saturday afternoon, called TRYING TO FORGET: WHEN THE PAST COMES BACK TO HAUNT YOU, with some serious company, CL Taylor, Alex Dahl and Robert Scragg, while the moderator is the one and only Alison Bruce.

If that doesn’t grab you, there are lots of other interesting events to be had over the weekend, ranging from examinations of crime scene procedures to crime-fighting technology, from spies and assassins to sweet old ladies who also happen to be serial killers. Big names attending include Ann Cleeves, Robert Goddard, Catriona Ward, Sarah Pinborough, Steve Cavanagh and Maxim Jakubowski, among many others.

CHILLERCON, Scarborough, May 26-29

Previously StokerCon and having been cancelled twice already due to the pandemic, ChillerCon, now with its own particular identity, has at last nailed down a slot for itself at the end of May and is already looking like one of the major horror fiction events of the year.

It’s going to be so big in fact that it will straddle two of Scarborough’s grandest and quirkiest hotels, the Royal and the Grand, which conveniently are only a matter of 50 yards apart, and occupy high ground overlooking the roaring surf of the North Sea.

If there’s anyone toying with the idea of attending but perhaps is concerned that horror as a genre is a tad too extreme for their taste, ChillerCon also features much to do with thriller and crime fiction, though it will all be strictly of the darker variety.

For example, check out some of the big names attending: Alexandra Benedict, Mike Carey, Mick Garris, Robert Lloyd Parry, Gillian Redfearn, James Brogden, Ramsey Campbell, Grady Hendrix, Stephen Jones, Tim Lebbon, Kim Newman, Sarah Pinborough and Catriona Ward.

Personally, I’ve got quite a bit of involvement at this year’s ChillerCon.

I’m delighted to announce that on the Saturday, May 28, I’ll be a guest on the panel, CRIMINAL MINDS: CRIME/HORROR CROSSOVER, which I’m guessing will do what it says on the tin, investigate the points where the two sub-genres meet and perhaps where they counter each other. It’ll be moderated by a master of ceremonies who’s well-known to all involved in both these fields (and adored by most), though I can’t name him yet, while sitting alongside me will be some serious luminaries of crime and horror (again, their names are embargoed at present, but watch this space).

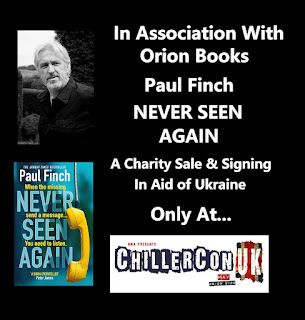

It should be a fun event, but that won’t be the end of my duties on the Saturday. A little later in the day, 5pm to be precise, in the Cocktail Bar at the Grand Hotel, I’ll be signing and selling copies of my novel,

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

, for a fiver each, all proceeds to go to humanitarian aid for Ukraine. There is obviously only a finite number of copies available, so it will need to be done on a first come first served basis. There will be complimentary drinks too, so you can always just come along for a chat.

It should be a fun event, but that won’t be the end of my duties on the Saturday. A little later in the day, 5pm to be precise, in the Cocktail Bar at the Grand Hotel, I’ll be signing and selling copies of my novel,

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

, for a fiver each, all proceeds to go to humanitarian aid for Ukraine. There is obviously only a finite number of copies available, so it will need to be done on a first come first served basis. There will be complimentary drinks too, so you can always just come along for a chat. MW CRAVEN: IN CONVERSATION WITH PAUL FINCH, Kendal, May 30

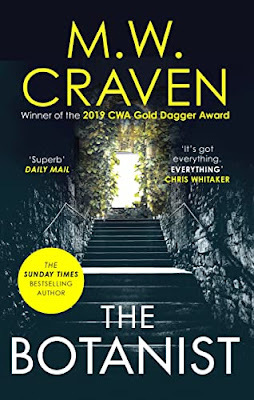

Closely following Scarborough, the next day in fact, I’ll be in Kendal in the lovely Lake District, where, in a special event organised by Waterstones in Kendal, held at 7pm at the Waterstones shop in the Westmorland Centre, I’ll be in conversation with MW Craven, a powerhouse crime writer and fellow craggy north-of-Englander, whose Washington Poe series has taken the crime and thriller world by storm in recent years.

His next novel,

THE BOTANIST

, sees Poe and his innocent civvy sidekick, Tilly Bradshaw, pursue a highly skilled poisoner, while at the same time having to cope with a convincing murder accusation levelled against one of their own colleagues.

His next novel,

THE BOTANIST

, sees Poe and his innocent civvy sidekick, Tilly Bradshaw, pursue a highly skilled poisoner, while at the same time having to cope with a convincing murder accusation levelled against one of their own colleagues. Mike and I will be discussing this, along with my own new book, NEVER SEEN AGAIN , in our usual nonchalant manner, plus anything else that comes up, cracking jokes, taking questions from the audience and the like.

If you’d like to get a ticket, just follow the link.

CRIME AT THE OLD COURTS, Wigan, June 11

Speaking of Mike Craven, I’ll also be guesting alongside him at this one-day event in my home town, Wigan. Mike will be celebrating publication of THE BOTANIST , but at the same time the day will focus on British crime writing in general.

I’ll be honest, there’s nothing I enjoy more than getting involved in events like these on home turf. There’s an old saying: ‘You can never be a hero in your hometown’. That’s undoubtedly true, but I feel I’ll have a chance to buck that trend if Wigan’s arts crowd continues its efforts to put their town on the crime-writing map.

This is the latest of several such events, and already it boasts an attractive line-up of guests. Aside from myself and MW Craven, also present will be Malcolm Hollingdrake, RC Bridgestock, Caroline England (left) and Patricia Dixon. Tickets for this one go on sale next week.

This is the latest of several such events, and already it boasts an attractive line-up of guests. Aside from myself and MW Craven, also present will be Malcolm Hollingdrake, RC Bridgestock, Caroline England (left) and Patricia Dixon. Tickets for this one go on sale next week.The event will run from 12 noon until 6pm in the evening, and will feature authors in conversation, books for sale, book signings, various of the sessions hosted by Caz and Sam from UK Crime Book Club. There’ll also be a licensed bar and refreshments. Again, for tickets and info for this one, follow the link.

THEAKSTON’S OLD PECULIAR CRIME WRITING FESTIVAL, Harrogate, July 21-24

This is one of the biggies, as they say. Even last year, when several regular events were still under cancellation due to Covid, the Harrogate festival – one of the most eagerly awaited and best attended in the annual crime fiction calendar, and now regarded as the largest celebration of the genre in Europe – made a very welcome comeback.

This is one of the biggies, as they say. Even last year, when several regular events were still under cancellation due to Covid, the Harrogate festival – one of the most eagerly awaited and best attended in the annual crime fiction calendar, and now regarded as the largest celebration of the genre in Europe – made a very welcome comeback.A part of the furniture in the genteel Yorkshire spa town of Harrogate since 2003, this grand occasion doesn’t just host the much-covetted Dagger Awards (as annually decided on and awarded by the Crime Writers’ Association), it presents panels, chats, readings, signing sessions, workshops, TV and radio interviews and the like, most of the action taking part in the historic Old Swan Hotel, and its beautiful and extensive gardens, and, all in all, is a phenomenal opportunity for fans and readers to mingle shoulder-to-shoulder with some of the true grandees of the industry, publishers, editors, agents and of course, the authors themselves.

In fact, after the non-event in 2020 and last year’s somewhat reduced convention, I suspect there’ll be even more of the latter this year than usual. Check out this list of the special guests who’ll be in attendance: Denise Mina, Lynda la Plante, Paula Hawkins, Tess Gerritsen, Michael Connelly, Lucy Foley, Charlie Higson, John Connolly, CL Taylor and Kathy Reichs … and there are likely to be more added to that list as we get closer to July.

For my own part, I’ll be doing my usual thing of propping up the bar, sitting in the sun and happily talking to anyone who feels like saying ‘hello.’

The second half of 2022 is not likely to be event-free, though it’s probably a little early in this uncertain world of ours to talk as though things from August onward are already set in stone. One thing I can definitely announce, though many details are yet to be ironed out on this one, is SFW XIII (the ever-popular – and I mean hugely popular – SCI-FI WEEKENDER) at Great Yarmouth, November 10-13. It’s a full weekend of panels with authors and media guests as well as great evening entertainment, and inevitably will go heavily on the themes of Sci-Fi, Fantasy and Horror.

I’m not sure what my role will be at this one, but I’ll definitely be attending and it’s yet another big event in 2022 that I can’t wait for.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE NORTH WATER

by Ian McGuire (2016)

THE NORTH WATER

by Ian McGuire (2016)

Outline

In 1859, Hull, on England’s Humberside coast, is a rough, tough whaling town where many dregs of humanity have washed up simply because there is nowhere else for them to go. One of these is Henry Drax, a loutish, drunken harpooner, who also happens to be a serial rapist and murderer of young boys. Not long after he’s shown up, Drax strikes again, firstly killing a fellow whaler in a pub fight and then attacking another child, raping and brutalising him to death, but feeling no concern that either of these crimes will have consequences as he’ll shortly be aboard the whaling ship, Volunteer, bound for the so-called North Water, the vast stretch of semi-frozen ocean that lies between Greenland and Canada in northern Baffin Bay.

At the same time, a desperado of a different sort arrives, also looking to join the crew of the Volunteer. Patrick Sumner is an Irish-born surgeon recently cashiered out of the British Army for some unspecified offence committed during the Siege of Delhi. Sumner, who came home from India wounded and with a laudanum habit, is here simply because he can’t find paid medical work anywhere else, and has no real idea what he is letting himself in for, having to live and work below decks among whalers, in a part of the world where the temperatures are so low that the sea itself freezes solid.

As if this isn’t going to be problem enough, the voyage of the Volunteer already feels as though it may be ill-fated. Brownlee, the skipper, while superficially efficient, has a reputation for being unlucky. His last vessel, the Percival, was ‘crushed to matchwood by a berg’, a full 18 of his crewmen dying in the process. The owner of the whaling company, Baxter, doesn’t fill Sumner with confidence either, and with good reason. Though only Brownlee is initially aware of it, this whole voyage is an insurance scam. Baxter has fallen on hard times. There are still plenty of whales in the sea, but paraffin is now replacing whale oil, and the whaling industry is dying out in towns like Hull. The shipping boss has thus instructed Brownlee to sink the Volunteer, but only when they are far into the Great White North, where the crew can be rescued by another ship of the fleet, the Hastings, but where there’ll be no possibility of an investigation discovering the truth.

As the voyage gets underway, other villains on board are drawing their own wicked plans. Having searched Sumner’s trunk, Drax and first-mate Cavendish, another reprobate, discover that he is in possession of a valuable ring that he possibly acquired in India. They have no doubt it would bring them a pretty penny if they could get hold of it themselves, but before then they must find a way to dispense with Sumner. Their first attempt to kill him misfires, when, during a sealing expedition on the pack-ice, he falls through a crevasse into the freezing water, and they leave him, only for the Irishman to prove doughtier than they expected, and live long enough to be saved by another crew member.

Debilitated through frostbite, Sumner has no option but to remain on board as the ship heads further into the frozen seas, now catching, killing and stripping down whales, which is a heartless, gruesome process, though in this desperate world the only interest anyone has is how much money they can make from it.

While the crew works, Sumner treats a cabin boy complaining of stomach problems. Giving him a full examination, the doctor discovers that the lad has been anally raped, though he is too frightened to name his attacker. Sumner reports to Brownlee, who, though he’s at heart an immoral man and knee deep in the prospective insurance fraud, is suitably angered by this to commence questioning the crew. Not long afterwards, the same boy goes missing, but is eventually found dead, strangled and stuffed into a barrel. It seems obvious that his rapist is the culprit, and Henry Drax spreads suspicion to a misanthropic ship’s carpenter called McKendrick, whom he claims he regularly saw in the boy’s company.

Convinced that he’s caught the villain, Brownlee throws McKendrick in the brig, but Sumner is less certain. For various reasons, he suspects Drax, though no one else will listen to him. Drax is amused by that, but now recognises the doctor as a potential foe as well as someone he wishes to kill for the purpose of robbery, while Brownlee is too preoccupied by the forthcoming disaster he must somehow manufacture to think this thing through. And all the while, as this incendiary atmosphere brews in the damp, muggy confines of the blood-soaked ship, the Volunteer sails further and further into the constant dark of the Arctic winter, and the perilous climes of the North Water …

Review

Though marketed as historical adventure fiction, The North Water is without doubt one of the darkest novels I’ve ever read. Ian McGuire is classified by many as a practitioner of ‘realist literature’, which, in a nutshell, means describing things the way they are, or were, on a warts and all basis.

So when you picture the grime and squalor below decks on a 19th century commercial whaler, particularly when it’s regularly awash with the blood, blubber and bone of the prey it has so mercilessly harpooned and then protractedly slaughtered, that is precisely what you get here. It is grim stuff, leaving no ugly detail to the imagination. And we are treated to similar when it comes to McGuire’s portrayal of an industrial northern port like Hull in the 1850s, where everything is smoky and grimy, where there is horrible dereliction, where human wrecks occupy the taverns and brothels, where violence happens all the time, where children sell themselves, and where a murderous animal like Henry Drax can blend in so comfortably. Even more affecting, we get similar with the Siege of Delhi, which we see in flashback; here, Britain’s war against the Indian uprising is depicted as a near-apocalypse, neither side showing mercy, multiple innocents caught up in the maelstrom, square-jawed British soldiers unrepentant at the carnage they’ve wreaked.

So yes, while this one is billed as a historical adventure, don’t be getting into The North Water anticipating some Boys’ Own yarn.

The star of the show, for me at least, is Henry Drax. A wolf in human clothing, he’s a predatory killer several decades before Jack the Ripper popularised such a notion. One might argue that such characters aren’t uncommon in scary fiction, but I’d riposte that it’s uncommon they’re as frightening as Henry Drax is. Ian McGuire demonstrates immense skill in his creation of a fictional person who you are literally unnerved by whenever he is on the page.

To start with, there is nothing charismatic or likeable about Drax. He’s not one of these loveable rogues, he’s not someone you ‘understand’ because of his hard background. He’s just a horror, and when you get into his mind, you can see that he’s utterly insane; he doesn’t understand why he rapes and murders, he doesn’t even enjoy it, but he knows that, when he does it, for a brief time at least he’s elevated to godlike status, which in serial killer terms, makes him as close as damn it to the real thing.

But it’s not just that he’s convincingly evil. At no stage, even when this guy is in chains, do you imagine that he’s not going to turn the tables and do something terrible all over again. In fact, as this narrative proceeds, your dread certainty increases that Drax won’t just prove difficult to dispose of, he’ll likely be the last man standing.

In sharp contrast, the hero of the book, Patrick Sumner, is a weak, rather diffident character. Again though, this is Ian McGuire being true to his realist agenda. Sumner is only here because he’s a failure. While he might essentially be on the right side of civilisation, he’s lost everything: his fortune, his reputation, his family, his home, his employability. Though there are quirks in his character even then. His precious ring was loot from the Mutiny, so Sumner made sure he got his share while others were dying. He was then infuriated with himself, not for doing what he did, but for trusting fellow officers who later betrayed him. Much of the time now, he lies in his bunk, drugged, feeling sorry for himself. And isn’t this exactly the way we’d expect one of those pink young men born of the upper classes in the Age of Empire to behave?

Later on in the narrative, when a missionary priest tries to help him, he is sullen and uncommunicative, and he justifies this to himself through his mistrust of religion (even though the religious man is out there providing medicine to the Inuits, while the great intellectual powerhouse of the world, the British Empire, is busy exploiting their homeland).

Ultimately though, we cling to Sumner as one of the few good men in this frozen hell. We have to root for him because, as the odds mount, there is literally no one else to root for.

At the end of the day, we’ve been on adventures in the polar regions before. But I don’t think many that I’ve read have been as visceral as this one. The cold bites you, you can smell the stink of blood and gangrenous flesh, the grime and brutality is all around us, and then, as I say, there is Drax, who stands out as a figure of evil even in this company.

The whole thing is incredibly well-written by Ian McGuire, who has an astonishing eye for the detail of an era now long and thankfully passed. It’s an adventure story, yes, but a bruising, brutal one that you won’t forget for many a year.

At this point in my book reviews I usually indulge myself with some fantasy casting for some imaginary movie or TV adaptation. That is impossible this week because The North Water has already been dramatised by the BBC, with Colin Farrel as Drax, Jack O’Connel as Sumner and the irrepressible Stephen Graham as Brownlee. I haven’t seen the TV series yet, but if it’s half as good as the novel, I’m in for a treat.

March 31, 2022

Abandoned flats, scary shadows, killer kids

Okay, well this week we’re still on the publicity trail for NEVER SEEN AGAIN. But don’t switch off too soon. Because I’ve got some new and exciting info on that front.

Okay, well this week we’re still on the publicity trail for NEVER SEEN AGAIN. But don’t switch off too soon. Because I’ve got some new and exciting info on that front. In addition, as a delectable treat (I’m sure you’ll agree), I’ve included a video of me reading a selected extract. It’s not a long piece, but something that I hope will capture the mood and suspense of the book.

On top of all that, on the topic of creepiness, eeriness, the chills to be had in the midst of everyday society and so forth, I’ll also be reviewing and discussing William Trevor’s very disturbing short novel, THE CHILDREN OF DYNMOUTH, which, if you have any appetite at all for truly dark fiction, I suspect you’ll gobble down in one sitting.

If you’re only here for the William Trevor review, no problem. As always, you’ll find it at the bottom end of today’s blogpost in the Thrillers, Chillers section. But before then …

In my own words

NEVER SEEN AGAIN is my latest novel. It was published earlier this month by Orion, and it falls firmly into the urban thriller category. It follows the fortunes of one David Kelman, a washed-up journalist, who, repentant though he is of the rapacious approach he brought to crime reporting in his junior days, now ekes out a lesser living by writing dirty stories about wayward celebrities. And then, suddenly, literally out of the blue, he gets a sniff of a story that could dramatically change his fortunes. Not just because it might well catapult him back into the big time, but because it could save the life of an heiress who was kidnapped six years ago and has long been thought dead, but whom David now knows is still alive and being held somewhere against her will.

The question is, does he do the good citizen thing and get the cops involved? Or does he do what David Kelman always does best, go it alone and bring home the goods entirely off his own bat, hogging all the glory and the kudos in the process. It was this latter method that got him in trouble in the past. But on other occasions it worked spectacularly. Why wouldn’t it work this time?

All right, enough with the sales pitch.

If you like what you’ve heard so far, you might be interested to know that, as of today, NEVER SEEN AGAIN has hit the ASDA charts today (not sure what number at, but I think 8 or possibly 7), which is something I’m inclined to shout about from the rooftops. It also seems to be hitting the sweet spot with Amazon, as two weeks since publication it can now boast 54 online reviews, the majority of them carrying 5-star ratings.

In the meantime, as promised, here’s a short extract from NEVER SEEN AGAIN , with yours truly in the reading chair. It focusses on a point in the narrative when David Kelman has followed a trail of clues to an abandoned apartment block in a bleak coastal town. Someone related to the investigation committed suicide here. David doesn’t know why, but it’s essential that he finds out ...

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE CHILDREN OF DYNMOUTH

by William Trevor (1976)

THE CHILDREN OF DYNMOUTH

by William Trevor (1976)

Outline

It’s the mid-1970s, and the Dorset town of Dynmouth is typical of the UK’s drab seaside resorts. It’s not a big place, and it isn’t one of those holiday hotspots for the working class like Blackpool or Margate, which are still thriving. The entertainments here have seen better days, there is little for the town’s youngsters to do and, aside from the sandpaper factory, nowhere for them to work when they grow up.

The town looks pretty enough, but it has its fair share of social problems, particularly at Cornerways, the local sink estate. However, there are also issues outside of Dynmouth’s poor quarter. Many local families have split in recent years and there is a general air of dissatisfaction. People don’t want to live here anymore, but they don’t know where else to go. They are distressed by the sight of local yobbos, the so-called ‘Dynmouth hards’, riding around on motorbikes in black leather jackets, but are too apathetic to report them to the police.

Weary Reverend Quentin Featherston considers it all a sign of the times. Society is changing dramatically, not necessarily for the better in his view, and even though the Easter fête is shortly due to occur, he fears that old traditions are disappearing and that the half-empty church on Sundays indicates people are no longer content with the promise of a happy afterlife. He also worries that he is not the man to deal with this, and that he looks ridiculous cycling about the town in his clerical collar and bicycle clips, trying to counsel people to whom he is irrelevant. He even suspects that his own family think him a fool, his twin daughters constantly playing up, his morose wife, Lavinia, not having fully recovered from a recent miscarriage, unimpressed by his belief in a benevolent God.

For the most part the vicar soldiers on, though there is one problem in Dynmouth that even the Rev. Featherston is flummoxed by. And that is the creepy 15-year-old, Timothy Gedge.

And when I say ‘creepy’, I choose my words carefully.

A strange-looking blond-haired boy from Cornerways, Timothy Gedge is the product of a home that is well and truly broken, his father having abandoned it years ago, his self-interested mother and promiscuous older sister persistently chasing their own pleasures, having completely neglected him during his most formative years. But Gedge is not an archetypal troubled youth. Though he’s in the habit of accosting people and engaging them in meaningless and meandering conversations, and perhaps more worryingly, is an habitual thief who will steal anything regardless of its value (and who in true predator fashion, mainly targets for theft the people involved around the church as they tend to be naïve and trusting), he doesn’t shout or swear or show any violent tendencies. He cross-dresses in private, in clothes he of course has stolen. But while none of these traits are endearing, they are not necessarily unusual.

What is unusual, and disturbing, is Gedge’s favourite hobby, which is following people around the town, learning all there is to know, and then, at some opportune time in the future, blackmailing them. And he’s obsessive when he does this. These people, often chosen at random, become his firm projects and their exploitation his raison d’être, and he won’t be thrown off-track, no matter what happens.

But even this isn’t the creepiest aspect of Timothy Gedge’s behaviour.

While he’s amassed quite a collection of nasty secrets that he knows he’ll be able to use in the future – pub-owner Plant’s affairs with married women in the town, war-hero Commander Abigail’s predeliction for boyscouts, and respectable married couple the Dasses’ heartbreaking fall-out with their neurotic and foolish son – he also has a fascination with death. He attends all the town’s funerals, and if anyone asks him, remarks that the best place for the people of Dynmouth is in coffins. As an extension of this morbidity (and this hints at an even darker side to his character), he plans to enter the Easter fête talent contest (having convinced himself that Hughie Green of Opportunity Knocks fame will be in attendance), where he intends to put on a one-man pantomime based on the ‘Brides in the Bath’ murders. It seems that 1900s wife-slayer, George Joseph Smith, once stayed at Dynmouth, and Gedge wishes to celebrate this by performing comedy routines about his trio of horrific crimes. For this he needs props: a bath for example, the type of suit the murderer wore, a wedding dress for when he’s impersonating the doomed brides. To obtain all these, his blackmail schemes go into overdrive.

But as so often happens with cool and confident villains, Timothy Gedge has finally reached the point where he’s about to overplay his hand …

Review

The first thing to say here is that, even though The Children of Dynmouth is one of the most subtle horror stories I have ever read, I doubt that Irish author William Trevor, widely regarded as one of the best short story writers of his age (and no stranger to the horror and supernatural genres), intended it to be anything of the sort. It’s more a two-pronged character study: both of a declining seaside town in a soulless age and the negative impact it has on the children trapped there, and of the most extreme case of this, Timothy Gedge.

But don’t assume that this is still, at heart, the simple tale of an underrage maniac terrorising a town. It isn’t anything like so straightforward. It’s much more the study of an unloved youngster from a deeply dysfunctional background, whose prurient interests have been allowed to fester, and whose alarming lack of self-awareness has turned him into a car crash just waiting to happen … but it’s also about those he preys upon, and what they should (or maybe must) do in their own defence.

Ultimately, Gedge is a narcissist, and malicious with it. The horrendous mental torture he puts his victims through is not to be sniffed at, nor diminished by sociological explanation. While we might feel sympathy for the youngster he was when all this started, he is already beyond recall, and the issue now is what to do with him. Other children in the town feel that he needs to be exorcised, most of the adults simply wish that he wasn’t there anymore (in other words dead or disappeared; they don’t care which), while the most enlightened character in the book, the Rev. Featherston, is lost for ideas but expects, as do we, that at some point in the not too distant future, Gedge will finish up in prison.

And yet none of these intricate complexities of thought and situation, or any of the book’s very rich character-work, is conveyed to us through simple exposition. Trevor sets the scene with delicious prose, but his descriptive method, while powerful, is succinct. He hits us with occasional introspective moments as various townsfolk try to process their latest experience of Timothy Gedge, regarding him as an irritant, an oddball, a nuisance, but the true depths of the boy’s bizarre villainy, and the nightmarish predicaments he routinely foists onto his neighbours, only really emerge during his unnerving encounters with these other characters, particularly the fast flowing dialogue in which Gedge’s glib tongue, unfunny jokes, disingenuous viewpoints and weird philosophies hit us like machine-gun rounds.

Despite William Trevor’s already unimpeachable reputation, I found all this remarkably well done and completely engrossing. I also found much of it chilling, hence my firm conviction that though a literary novel, The Children of Dynmouth is firmly classifiable as ‘dark fiction’. The scene in which Gedge makes a phone-call attempting to impersonate the female concierge at the local cinema in an effort to lure out 12-year-old half-siblings, Stephen and Kate Fleming (perhaps his most cruelly abused victims) and even though he is quickly rumbled, persists with the charade, unwilling to acknowledge defeat, is suggestive of a true psychopath and genuinely disturbing.

But I reiterate: this isn’t a straightforward thriller.

Towards the end of the book, when the jig is basically up, and we identify the root cause of Timothy Gedge’s behaviour and it’s heartbreakingly sad, it comes as a massive wrench because up until now we’ve hated the boy.

Call this book a thriller if you want, or a mystery, but there’s so much more going on. It’s dark stuff, for sure, by turns distressing and frightening, but also sad and thought-provoking. It would be too easy to write Timothy Gedge off as evil or insane (as so many here do), but he’s also a human being, albeit badly damaged.

He is every inch one of The Children of Dynmouth .

Here we go, I’m now, yet again, going to embarrass myself by trying to cast this tale in advance of some imaginary film or TV production. (If there already has been one, you’ll have to forgive me, as I’m unaware of it at present).

Featherston – Richard E Grant

Gedge – Noah Jupe

March 14, 2022

Tension grows as publication draws closer

Another totally gratuitous blogpost this week I’m afraid, as this Thursday, March 17, sees publication of my next novel, NEVER SEEN AGAIN. For those who think I may be carrying this thing a bit far, that it’s all a tad self-indulgent to keep going on about this, that you’ve heard it all before, yadda yadda … I can only apologise.

The best we authors can usually hope for is to have one of our books published each year (though sometimes two … you never know), so I’m very excited. And anyway, all kinds of things are happening, so it’s not like I’ve nothing new to report.

In keeping with today’s theme, exciting thrillers, I’m also pleased today to offer a detailed review and discussion of the late, great Philip Kerr’s very classy period piece, THE PALE CRIMINAL.

As usual, if the Kerr review is your main interest, you’ll find it at the lower end of today’s post in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

Almost time

Almost timeBefore then, we’re going to talk about the near-imminent publication of NEVER SEEN AGAIN , which, even if I say so myself, is a beautiful thing. Here is a shot of me holding in my hand the very first one off the press.

In addition to that, as you can see topside, an exciting looking blog tour commences today.

I adore these. For those unfamiliar with the concept, in each case, on each day, a different blogger will offer a review and/or a bit of incisive chit-chat about the title in question (and this time, of course, it happens to be mine). Either way, review or gossip, these book-blogger folks do a sterling job. They really are one of the best methods we have for getting the word out these days. I always appreciate it when I’ve got a new title due, and quality book-persons like these come on board and put in a good word. Many thanks to all those involved.

Not that NEVER SEEN AGAIN hasn’t already passed through the hands of quite a few august individuals. You may have noticed that it’s accrued some great quotes from fellow authors I really rate.

Check these out.

Exceptional crime writing. Paul Finch continues to raise the bar.

MW Craven

A spine-chilling mystery from the master of suspense.

MJ Arlidge

This might be Finch’s best yet … Grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go.

PL Kane

A cracking crime thriller that builds to an action-packed finale. Guaranteed to elevate your heart-rate!

David Jackson

I should also say, and this is the bit where today’s post REALLY gets self-indulgent, that with three days still to go, we now have some very effusive write-ups on NETGALLEY .

Here are a few choice quotes:

It is so tense that I had to keep putting it down for a breather. *****

Elaine T

The story is paced perfectly, the underlying mystery so carefully threaded throughout the book that it kept me completely engrossed in the story. *****

Jen L

One of the best thrillers I have read in a long time and in my opinion the best book I have read by this author. *****

Peggy B

Gripping and compelling with an engaging storyline and explosive characters. *****

Ariah H

I felt very honoured to read these, as the whole purpose of NETGALLEY is that reviewers participating are required to give a completely honest appraisal. It’s not in their interest to fib for the sake of the author or publisher; they would gain nothing from that. My heartfelt thanks to all, so far and still to come, who have taken a chance on NEVER SEEN AGAIN .

A bit of a bargain

I also hear, by the way, that there is a nice little bargain on the horizon.

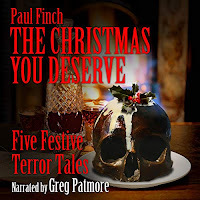

Apparently, my stand-alone crime thriller of 2020, ONE EYE OPEN , will be available on Audible for ONLY £3 as part of a special promotion this Wednesday (March 16).

Yes, you read that correctly. ONLY £3.

Yes, you read that correctly. ONLY £3. For those of us who like to receive our fiction while we’re out walking the dog, or working on a treadmill, or driving on the motorway, or even riding an inter-city train, that’s got to be something to consider, yeah?

For those unaware, ONE EYE OPEN features a character who, at the time, was new to my books, DS Lynda Hagen, a former detective now turned road traffic accident investigator (primarily so that she can look after her kids and deal with her neurotic husband), who attends what appears to be a routine smash on the A12 in Essex, only to find a big mystery, which soon leads her down a rabbit hole into a terrifying world of armed robberies and organised crime.

As I say, the Audible version of ONE EYE OPEN , as performed by Louise Brealey, can be yours for the remarkable sum of £3 for one day only, March 16 (no coincidence, I suspect, that this is the day before we launch NEVER SEEN AGAIN ).

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE PALE CRIMINAL

by Philip Kerr (1990)

THE PALE CRIMINAL

by Philip Kerr (1990)

Outline

Berlin, 1938. Bernie Gunther, a former homicide detective now self-employed as a private eye, is working less than inspiring cases. Though he’s recently enlisted another ex-cop, Bruno Stahlecker, as his assistant, things still aren’t too exciting. They are currently investigating an attempted blackmail against the head of a major publishing company whose homosexual son has been writing indiscreet letters to his lover, a noted scientist called Lanz Kinderman.

It all seems pretty mundane and the two detectives finally break the case when they trace the letters to Klaus Hering, one of Kinderman’s recently dismissed employees. But during the course of this fairly innocuous enquiry, the likeable Stahlecker is shot and killed and a short time later, Hering, the main suspect, found hanged, presumably by his own hand.

Almost immediately afterwards, maybe coincidentally (or maybe not), the disheartened Gunther receives an order to attend Gestapo headquarters, where he meets two people who really existed in history, Arthur Nebe, head of the Kriminalpolizei, or Kripo, the Criminal Police Force of Nazi Germany, and more unnervingly, Reinhard Heydrich, Chief of Reich Security, a senior SS member and already a figure of terror to many.

However, for the moment, neither Nebe nor Heydrich are concerned with an issue of state; for once it is something a little more mundane, though it is bothering them a great deal. It hasn’t been publicised much, but a serial killer is operating in Berlin, sexually murdering school-age girls, specifically those who fit the Aryan ideal, i.e. pretty, blonde and blue-eyed.

With the force’s current batch of detectives unable to stop the atrocities, and in fact being made a mockery of, Gunther is commanded to reorganise the enquiry and take the role of lead investigator.

Unwilling to voluntarily assist the Nazi authorities, but seeing this cause as worthy (and given little choice in the matter anyway), he is reinstated to the police at the rank of Kriminalkommissar and given a dedicated team of Gestapo officers to work underneath him, including the crude, womanising Becker and the stiff but more-useful-than-expected Korsch.

Assisted (though sometimes hindered as well) by this misaligned bunch, Gunther works his way through a plethora of leads, all of which seem promising at first.

When Joseph Kahn is brought in, a Jewish oddball, who on the face of it at least seems a very likely suspect, an investigating psychiatrist casts doubt on his guilt and in fact Kahn commits suicide in custody, only for the real killer to then strike again.

Another possibility, one that Gunther likes particularly, centres around Gottfried Bautz, an ex-military fanatic with a long track-record of sexual violence, but yet again, Bautz is in custody when the prolific killer claims another victim.

And then the case takes a turn that none of the detectives are comfortable with.

From forensic investigations carried out by skilled pathologist, Hans Illman, it is concluded that all the murder victims to this point have been hung upside down and allowed to drain of blood. The cops purposely withhold this intelligence from the public, only to have their attention drawn to a grotesque cartoon in the widely-read Nazi propaganda periodical, Der Stürmer , depicting ‘German victims of Jewish violence’, all of them young women, all of them ritually strung upside down and allowed to bleed out.

Its publisher, Julius Streicher, a rabid and violent anti-Semite (and again a real historical personality), is a man of gross sexual habits, and despised by almost everyone who knows him as a boor and a brute. So, when a witness statement places a Streicher lookalike close to several of the crime scenes, it feels as if Gunther at last has a viable suspect. However, Julius Streicher also happens to be a senior administrator in Hitler’s government and, as Gauleiter of Franconia, a virtual czar in his home town of Nuremberg, which sits in the very centre of the Nazi heartland …

Review

There are 14 Bernie Gunther novels, of which The Pale Criminal was the second, all written by the late British author, Philip Kerr, though the first three, something of an entity in themselves, were published much earlier than the rest, between 1989 and 1991. Such was their acclaim that in crime-fiction circles even now they are referred to as the ‘Berlin Noir trilogy’.

And that is completely the atmosphere that Philip Kerr sought to create. His pre-war Berlin is a maze of dark and winding backstreets, drinking holes of ill repute and seedy stairways ascending to decayed garrets wherein prostitutes and pornographers can be found. Meanwhile, in Bernie Gunther, Kerr gave us a youngish (going on middle-aged) protagonist, hardened by his previous experiences as a soldier and a cop, with no loved ones to speak of (none of whom are alive), no real talent other than his ability to catch crooks, and an outlook on life that is cynical and wry, but also relaxed. He’s a tough cookie who instinctively believes the worst of people, but he has a grim sense of humour, which manifests in regular and amusing wisecracks.

Like the Chandler-esque heroes on whom he is based, he also has a deep mistrust of authority, so much so that he’s now his own man, still chasing bad guys but mostly independently, as wary of the police and judiciary as he is the underworld.

Of course, in Gunther’s case there is a genuine, full-on reason for this. The civilian police force he joined after being demobbed from the army at the end of World War One is now under the control of the totalitarian Nazi regime. Every day, the freedoms Germans enjoyed during the Weimar Republic are being curtailed, and with Hitler’s constant provocations aimed overseas, the next war doesn’t feel very far off.

It’s ironic, therefore, that in The Pale Criminal, Gunther finds himself with no option but to assist these Swastika-clad bullies in their hunt for a monster of the street-level variety.

And to be frank, I don’t blame Kerr for taking this diversion. Because which purveyor of historical crime fiction could resist the inclusion in their latest novel of such real-life personalities as Heydrich, Himmler and Julius Streicher? And it doesn’t stop there. Much like Chris Petit with his exceptional The Butchers of Berlin (even though that was written 25 years later), Kerr revels in the opportunity to breathe life into some of the great villains of history.

To a degree, this goes exactly the way you’d expect. Top cop Arthur Nebe, for example, who though in later life he was hanged for his involvement in the plot to assassinate Hitler, was regarded by the Allies as a Holocaust facilitator who would likely have faced prosecution had he lived so long, and in this book he embodies that role, appearing as a classic fence-sitter. Otto Rahn and Karl Weisthor, meanwhile, though SS officers, were also known for their bizarre behaviour and occult obsessions, and in Kerr’s hands this is taken to new extremes, the pair of them portrayed not just as fanatics, but as individuals who are quite patently insane. Meanwhile, Julius Streicher, or ‘Jew-Baiter Number One’ as he liked to term himself, is every inch the ill-mannered cur that he was regarded as during his actual life, while with Himmler, though this book mostly concentrates on his fascination with mysticism and so depicts him in less belligerent form than usual, we still get the feeling that below his calm exterior lies a dangerous madman.

But it is Heydrich, the Butcher of Prague and chairman of the infamous Wannsee Conference, whose presence in this novel I found most intriguing. In real life, of course, Reinhard Heydrich was killed in 1942 by Czech commandos, and at the time considered no loss to humanity due to his irredeemably evil reputation. In Kerr’s version, however, we see a much more reflective character. An arch-controller who we’re in no doubt can authorise violence at the drop of a hat, but a man serious about his role as a government official, someone who doesn’t want war with the Allies and who sees it as his duty to maintain order and stability in the new Germany … even to the extent where he is concerned that pogroms against the Jewish community might damage the economy. In fact, this is the entire reason behind his hiring of Gunther, a proven homicide cop, who is separate from the main police and can be relied upon to bring in this brutal slayer of Aryan daughterhood without the blame being passed to the Jews.

This is certainly not the utterly ruthless and anti-semitic Heydrich that I thought I knew from history, but then The Pale Criminal is set in 1938, and maybe it’s the case that many of these extreme Nazi villains only grew into those roles gradually as absolute power absolutely corrupted them. (It could also be a double-bluff, I suppose, because if Heydrich genuinely was ambivalent to the Jews in his early days, his willingness to annihilate them only a few years later more than hints at a deeply disturbed personality).

But that’s The Pale Criminal and how it relates to history.

What about the story itself?

Well, like all good mysteries, it’s a page-turner. Kerr focusses tightly on the investigation, the twists coming thick and fast, many of the lesser characters simply servicing the plot though they’re all very visible and believable.

Gunther himself makes an appealing hero, though a warning in advance. This book is set in the 1930s and subsequently contains few modern attitudes. Homosexuality was illegal then even in Britain (and viciously punished in Nazi Germany), and that’s on full display here. At the same time, the police use violence routinely, both against people and property. Interrogation of suspects includes lots of roughhouse – and Gunther participates in this as much as the others. He’s also guilty of lusting after almost every woman he meets, including a high-ranking female psychologist and even Hildegard Skeininger, the beautiful but heartbroken mother of one of the child victims … though to be fair to Gunther, he’s never especially ungentlemanly.

Kerr’s writing style is always accessible and there are few complexities in the case, the story bouncing along at a jaunty pace against an ongoing atmosphere of menace provided by the Nazis but studded with occasional and welcome bouts of humour.

I earlier mentioned Chris Petit’s dark masterpiece, The Butchers of Berlin , but the tone here is far lighter than that. In The Pale Criminal , Germany has not yet descended into a fiery wartime Hell. You really get the impression that well within the living memory of almost everyone in the book, this society had once been civilised and democratic, and that many of the officials our main character encounters haven’t yet adjusted from that. Life for many goes on as normal.

All round, this is an excellent and atmospheric thriller. There are no massive surprises, but it’s a fast, compelling read, its authentic historical setting adding much more than lurid background colour.

And now my usual folly. I’m going to imagine The Pale Criminal as a movie or TV show, and cast it right in front of you. I don’t know if anyone’s ever attempted this in real life, but I’d be delighted if they did

Bernie Gunther – Tim Roth

Hildegard Skeininger – Teresa Palmer

Professor Hans Illman – Christoph Waltz

Julius Streicher – Gary Oldman

Arthur Nebe – Philip Jackson

Frau Lange – Emily Watson

Reinhard Heydrich – Hugo Weaving

Becker – Alex Høgh Andersen

Korsch – Tom Felton

Rolf Vogelman – Thomas Gabrielsson

Otto Rahn – Joseph Fiennes

Karl Weisthor – Rhys Ifans

Lanz Kinderman – Bill Nighy

February 16, 2022

Counting down the days with my top five

I can’t pretend that I’m not getting very excited about the publication of my next novel, NEVER SEEN AGAIN, on March 17. So excited in fact that I’ll be focussing primarily on my own writing today (so, sorry about that in advance). In short, I thought today might be the ideal opportunity to look back through my crime thriller output of the last few years, and select what I consider to be my best five novels to date, with a little bit of info attached to each one just to illustrate why and how I came to this conclusion.

It isn’t going to be totally about me, though. On the subject of hard-nosed crime thrillers, particularly those featuring journalists rather than cops (in keeping with NEVER SEEN AGAIN ), I thought today would also be the perfect time to review and discuss the late, great Mo Hayder’s exceptionally frightening and intriguing mystery, PIG ISLAND.

If you’re only really here to read about that, it’s no problem. You’ll find that review/discussion, as usual, at the lower end of today’s blogpost in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

Again as mentioned at the top of this page, and I’m particularly stoked about this, publication of my twelfth crime novel to date, but only my second with Orion Books, is imminent. Anyone who’s interested in this stuff will have noticed a slight change of tone since I went to Orion, though as I keep reiterating to the many readers who continue to get in touch (for which I’m very grateful, by the way), the Heck and Lucy Clayburn series are far from finished – it’s just that my focus of the last few years has been on stand-alone thrillers rather than series.

ONE EYE OPEN

was the first of these, and

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

will follow in that tradition, though all my crime novels are set in the same universe. Throughout them, you’ll spot references to the National Crime Group, the Organised Crime Division, the Serial Crimes Unit, and so on, while characters who have background roles in some will have foreground roles in others etc.

ONE EYE OPEN

was the first of these, and

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

will follow in that tradition, though all my crime novels are set in the same universe. Throughout them, you’ll spot references to the National Crime Group, the Organised Crime Division, the Serial Crimes Unit, and so on, while characters who have background roles in some will have foreground roles in others etc.But NEVER SEEN AGAIN brings us an entirely new investigator in the shape of David Kelman, and for once he’s not a cop.

A disgraced crime reporter, Kelman’s life has gone to pieces over the last few years. Basically, he blew a confidence, which had catastrophic results; not just for him personally and professionally, but for his newspaper and for the life of a young heiress who’d been kidnapped. Six years have rolled by since then, and David, no longer respected in the industry, can only scratch a living by writing celebrity shockers for the scandal mags. Which macho and married TV personality is currently courting male prostitutes? Which respectable film star has a criminal past that she’d rather forget? And so on.

Until, very unexpectedly, he is offered an opportunity not just to redeem himself, but to save the life of someone he thought long ago murdered. But the problem is that no one trusts him and no one will work with him. So, he’s going to have to do this all on his own, and follow a path that will take him into a dark, dangerous world of racketeering, crooked cops and professional killers.

I’ve often traded on the fact I was a cop before I became a full-time author. But I had another job between the two. I was a journalist working for a range of newspaper titles across the Northwest of England. I want to stress right now that the real me was no more a David Kelman than he was a Mark Heckenburg. In reality, journalism is a responsible job, where the onus is on you to impart the news without prejudice and to get your facts right, rather than to sensationalise every bit of tittle-tattle that comes along in an effort to sell papers.

Okay, I get it that some of our more recent media darlings seem to have forgotten this message. But that was the jist of the role, as I knew it.

But as with police officers, the life and work of a journalist can be very intense and even dangerous. The possibility is always lurking that, if you get something wrong – badly wrong – it could have dire consequences. While the big difference between a cop and a journalist is that, if you’re going to get into the guts of some very bad people, the journo has very little muscle to call on as backup. He/she going to be walking a lonely and high-risk path.

This, in a nutshell, was the thinking behind NEVER SEEN AGAIN . I’m very proud of it, even if I say so myself, but the proof is only in the eating. So, I am still eagerly awaiting March 17 and to see the first responses from neutrals.

By the way, if there’s anyone who’s really desperate to get their hands on a copy before then, the NetGalley option is open as always. Just go HERE .

And now, as promised …

My favourite five

In chronological order.

STALKERS

(2013)

STALKERS

(2013) This was my first crime novel to hit the mass-market, courtesy of Avon at HarperCollins. STALKERS introduced my primary cop character, DS Mark Heckenburg. A loner detective working for Scotland Yard’s elite Serial Crimes Unit, Heckenburg, or Heck, a northerner displaced to London to escape a tragic past, which has left him almost friendless in his homeland, is now part of a specialist team that tracks serial offenders, mainly rapists and murderers, across all the police force areas of England and Wales. He is tough and resourceful, an habitual risk-taker and rule-bender, but in many ways he’s quite vulnerable too, not least because of the sexual chemistry he shares with Detective Superintendent Gemma Piper, a by-the-book officer but his former girlfriend when, back in the day, they were detective constables together, though now she’s his boss and someone he doesn’t see eye-to-eye with on most law-enforcement techniques.

In STALKERS , Heck’s first outing, he pieces together a confusing number of disappearances by uncovering the presence of the Nice Guys, a secretive crime syndicate whose racket, to be blunt, is a rape club. At the behest of high-paying clients, they kidnap named individuals to order and then provide a private location in which they can be sexually attacked and murdered, before undertaking to dispose of all the evidence.

STALKERS is still one of my best-selling novels, and it produced a lead character who proved to be very popular with my readership (over 260,000 copies sold thus far). Such was its success that it directed me firmly into crime-thriller territory, whereas previously I’d written widely within horror, sci-fi and historical fantasy.

SACRIFICE

(2013)

SACRIFICE

(2013) This was the second Mark Heckenburg novel, and to date it remains Heck’s main contribution to the folk horror genre. In it, Heck, Gemma and the rest of SCU go in pursuit of a ‘calendar killer’, an unsub (or group of unsubs) nicknamed the Desecrator, who abducts people at random and sacrifices them in gruesome ways to celebrate ancient folk festivals, many of which have become little more in the 21st century than fun nights out: a drunk burned alive on a bonfire on Guy Fawkes Night, for example; a tramp dressed in a Father Christmas suit and walled into a chimney on Christmas Eve; a pair of young lovers shot through their respective hearts by a single arrow on Valentine’s Day. I think you get the drill.

A horror buff from years back, I was really delighted when the staff at Avon went for this idea. It allowed me to let rip with some truly ghastly murders and to delve deeply into the mysterious rites, some of them quite sinister, that lurk behind many of our most innocent traditions.

Funnily enough, my initial plan was to run this story from late summer, through the autumn and into the winter, but having scoured the calender for meaningful days, it soon became apparent that there were far more to choose from in the spring. The killing spree thus starts at Christmas and extends to May.

There’s quite a high body-count in this one, and I like to think some spectacularly twisted baddies. It remains my favourite Heck novel to date.

STRANGERS

(2016)

STRANGERS

(2016) This novel first appeared at the request of Avon, who, while they were happy with the Heck novels, were keen to see a parallel series featuring a female protagonist. Although Lucy Clayburn already existed, at least on paper.

Well over a decade earlier, I’d speculatively written a television drama called Dirty Work , centred around a young female police detective in Manchester, who was blue-collar in origin and highly competent but regarded with suspicion by many of her male colleagues because she’d blown the whistle on a bunch of corrupt officers early in her career. The main investigation in Dirty Work was into a series of torture-murders of underworld figures, which, it later transpired, was the response of another cadre of corrupt cops who were looking to cover up past indiscretions and avert the exposure of a significant number of miscarriages of justice.

Miscarriages of justice were big news at the time, the early/mid-1990s, but they weren’t by 2016, when HarperCollins were looking for their own Lucy Clayburn series. The story had to be changed, as did certain aspects of Lucy’s personal circumstances, owing to these having (mysteriously, in my view) appeared on another TV cop show (after Dirty Work had been touted around for quite a while). As such, the Lucy who appeared for the first time in STRANGERS was still a junior police detective in Manchester, came from a poor background, was the child of a single mother etc, but now there were additions, and these, for my money, were a huge improvement. She rode a Ducati M900 because she had a Hell’s Angel past, there were still problems with some of her colleagues, this time because she’d made a mistake during her first week in CID, which had seen her DI shot and wounded. But the real complication in her life – though it doesn’t come to the fore in STRANGERS until later in the story – is that only long after she’d joined the police did Lucy learn that she was the estranged daughter of Frank McCracken, a major organised crime figure in Northern England.

In STRANGERS , she gets the chance to redeem herself by going undercover as a streetwalker to try and snare a female serial killer known as Jill the Ripper, a deranged prostitute responsible for the sex murders of a number of her male clients.

Though a dark tale indeed, STRANGERS turned the traditonal murder mystery on its head in that men were the targets for a female slayer, and involved lots of research on my part, mainly with policewomen and ex-policewomen friends of mine who had done this very job (i.e. getting into their scanties and going out on the backstreets at night to catch bad uns). Thankfully, all these efforts seemed to pay off, as STRANGERS remains one of my most successful novels to date, having made the Sunday Times Top 10.

KISS OF DEATH

(2018)

KISS OF DEATH

(2018) My latest Heck novel, though there are more coming (trust me). This one takes note of the recent wave of police cuts, and sees the Serial Crimes Unit in grave danger of being disbanded as many of the top brass consider it a luxury. Gemma Piper, in an effort to save her unit, agrees to take on Operation Sledgehammer, the pursuit of the UK’s twenty most dangerous fugitives from justice who are still believed to be in the country. These are mass murderers all, gangsters, hitmen, serial rapists and the like. Heck and his new partner, the spiky but efficient Gail Honeyford, are put on the trail of a bank robber who often kidnaps and murders, but soon find evidence that a much more terrible game is in play.

Many of these men, it seems, are not missing because they are on the run, but because they themselves have been abducted for some nefarious purpose, and straightforward vigilanteism does not seem to be the explanation. In due course, Heck breaks open a conspiracy so horrific that even the Serial Crimes Unit hasn’t seen its like before. And finds it the work of a power so fiendish that even the UK’s worst criminals are little more to it than pawns in chess.

I consider KISS OF DEATH to be the most action-packed and violent of the Heck novels, but it’s become more famous since it was published for it’s so-called WTF ending (as I hoped it would at the time), which unfortunately I wasn’t able to follow up straight away because I was in the process of changing publishers.

I can only assure my readers that this story has not ended, that Heck will return, and that the next novel following on from this one is already written and now awaiting its publication slot.

ONE EYE OPEN

(2020)

ONE EYE OPEN

(2020) My first novel for Orion, and one of my favourite pieces of work to date. It starts on a quiet road in Essex, where DS Lynda Hagen, a Serious Collision Investigation officer, enquires into a bizarre road accident in which a cloned car has veered off a highway into the woods for no apparent reason, severely injuring the two people on board, neither of whom are initially identifiable.

Lynda is a former CID officer who once dealt exclusively with crime. She only moved into Traffic because having two kids to raise and a husband struggling to recover from a nervous breakdown necessitated ordinary nine-til-five hours. But she still has well-honed detective instincts, and increasingly starts to suspect that this is no common-garden RTA. She can’t expect at this stage though, that it will lead her into a deadly world of armed robbery, organised crime and an underworld resource deemed so valuable by England’s various vying crime syndicates that they will kill and kill and kill to get their hands on it.

ONE EYE OPEN took me right out of my comfort zone. It was the first crime novel I’ve written that didn’t also double as an action thriller. It does include a heist and a police pursuit sequence that one reviewer described as ‘the best I’ve ever read’, but it’s much more of a complex mystery, involving unreliable narration and non-linear time zones. Don’t let that put you off, though. It still features moments of what I hope are extreme suspense, even terror, and finally reaches what another reader described as ‘a great ending’.

I feel a bit self-conscious singing my own praises here, but that’s what today’s blog is all about (and you were warned in advance).

Anyway, these are the five crime novels that I consider I’ve done my best work on. Hopefully more will follow, maybe starting with NEVER SEEN AGAIN , which I reiterate is published on March 17. At the end of the day, of course, only you readers can be the final judges.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

PIG ISLAND

by Mo Hayder (2006)

PIG ISLAND

by Mo Hayder (2006)

Outline

Joe Oakes is a rough-cut Liverpool-born investigative journalist, who specialises in exposing supernatural hoaxes and bringing charlatans to public ridicule. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it doesn’t pay brilliantly well, and this, along with his self-employed status, is a constant problem for his attractive, middle-class wife, Lexie, who loves her hubby in her own way, but is increasingly tempted to stray towards the good-looking Harley Street doctor for whom she works as a receptionist.

Despite Oakes’s hit-and-miss reputation, he does have one very successful job under his belt. Back in the day, he travelled to the States and blew the gaff on British-born Evangelical faith-healer, Malachi Dove, who was conning people out of millions by performing fake life-saving surgeries ‘through prayer’. But that was in the past. The pickings have been leaner since then. However, very unexpectedly, Oakes gets a chance to revisit this glory when he learns that Dove has not disappeared into complete obscurity.

When mutilated body-parts, identified as having come from pigs, wash up on Scotland’s west coast, suspicion turns towards the small community on the isolated isle of Cuagach, better known as Pig Island. Oakes gets interested when he hears that the small group, who recently set up there as the ‘Psychogenic Healing Ministries’, are a satanic cult, and even more so when he learns that their pastor is one Malachi Dove.

The mystery deepens when shoddy video evidence taken by a tourist on a fishing boat appears to depict a half-human / half-animal hybrid walking on the Pig Island beaches. Local people on shore are convinced that the cult on the island, probably having performed sacrificial ceremonies which afterwards involved disposal of the animal parts, have raised a demonic entity: Pan, or maybe the Devil himself. Oakes is not so sure about that, but very sure that if Malachi Dove is involved, it will need to be investigated.

Rather to his surprise, when he contacts the Psychogenic Healing Ministries, they invite him to the island, saying that they abhor the rumours circulating and that they hope, if he comes for a visit, he will afterwards write about their activities, showing that they are not Satanists, just ordinary people looking for a new, simpler direction in life.

Oakes arrives on the island and at first glance sees only what the community spokesmen describe: friendly villagers, small, cheaply-constructed cabins, a meeting hall, and a chapel built into the rockface of a cliff, though it seems a little odd that this chapel possesses high-level security. What he doesn’t find is Malachi Dove, and when he enquires about this, he is told that the pastor has lost his mind and now lives in seclusion on the other side of the island. Oakes wants to go over there, but is advised not to by the nervous community.

This is a red rag to a bull, and at the first opportunity, the journalist attempts to cross to the other side of Cuagach, only to find that the area where Dove allegedly lives has been barricaded off by a ditch filled with drums of toxic waste and a tall, electrified fence along the top of which pigs’ severed heads have been set as warnings.

Despite these alarming fortifications, he manages to infiltrate Dove’s domain, even entering the exile’s squalid hovel of a house. When he discovers evidence that the madman has been butchering pigs as part of a ritual, having first attempted to exorcise demonic souls into their bodies the way Jesus did with the Gadarene Swine, he thinks he’s seen it all.

But he hasn’t. Oakes doesn’t know it yet, but there is much, much worse to come …

Review

The late great Mo Hayder had a reputation for infusing her thrillers with gruesome detail, often pushing them over the dividing line into the horror genre. This is very much in evidence with Pig Island . However, appearances can be deceptive, because first and foremost this novel is a crime story, albeit a gory and disturbing one.

But you know, you have to admire an author who so fearlessly tackles the sordid realities of life on humanity’s fringes. Forget the half-human creature, forget the rumoured witch-cult, forget the flyblown pig’s head totems on the boundary fence … much of the horror to be found here is of the grimly authentic kind: the squalid interior of the dwelling where an isolated misanthrope has been eking out a solitary, embittered existence; the rundown, needle-strewn housing estate where a police safehouse allows government witnesses to hide in plain sight (and to feel lonely and cut off from the world they knew); the grotesque details of the medical procedures required to repair the body of a young woman who has not just been beaten and sexually assaulted, but also burned; the day-to-day existence of a badly disabled girl who has found herself an object of scorn, fear and twisted sexual desire.

Yes, this is Mo Hayder country for sure. No taboo is too unsettling for her to examine it in unstinting detail.

But does it work as a thriller?

Well, we’re already in the world of hybrids. We have a hybrid creature lurking on Pig Island, and as I say, a hybrid narrative. It starts out with a near-Weird Tales feel, the intrepid journalist venturing to an eerie isle where a monster allegedly roams and the locals worship Satan, but then morphs into something – dare I say it – a little more mundane: a murder mystery filled with taut investigative police detail.

Does that spoil it?

Well, it jars a little on first reading, but all in all, Pig Island remains a very satisfying story, which is filled with tension, suspense and, when necessary, violence, and which ends on a real high note if you enjoy being shaken out of your wits.