Michael Hyatt's Blog, page 53

November 14, 2017

Anatomy of a Tough Talk

Our success as leaders often comes down to one thing. Not our planning. Not the market. But, instead, the conversations we lead. When stakes are high (and emotions even higher) you need a solid game-plan. In this episode, we break down a three-phase strategy for winning with your next crucial conversation.

The Right Way to Fire the Wrong Person

5 Steps to Letting People Go Humanely

“Does it get easier the more people you fire?” someone once asked me. I’ve been in leadership for decades now, and there’s no escaping letting people go from time to time. But that doesn’t make it easier. “No,” I said, “it hasn’t. And I hope to God it never does.”

But while frequency doesn’t translate to ease, it can translate into useful experience. I’ve learned there’s a right way and a wrong way to let people go when it’s necessary. I’ve also learned that how we do it matters for health of our organizations. Let’s start by looking at the wrong way to do it.

No letters or boxes

Early on in my career, I was with a company that decided to lay off five people who were in the field, selling in the midst of a recession. The sales manager should have flown out and met with each of them individually to deliver the bad news. At the very least he could have picked up the phone and called them.

Instead, he sent them the corporate equivalent of Dear John letters. They literally got a letter in their mailbox at home saying their job had been eliminated.

The damage from that sort of treatment is unbelievable—not only for the individual, but for the company. First, it affects the entire team’s morale. Those left standing say to themselves, “So that’s what they think of us,” before sending their resumes to companies that might treat them better. Second, it poisons the applicant pool. Potential employees hear the story and look elsewhere.

When I became CEO of Thomas Nelson, we had an old-school firing policy. If you were let go, somebody from human resources escorted you to your office with a box. They waited while you packed and walked you out of the building when you were done.

To me, that was not acceptable. That sort of treatment might be necessary if you work for the CIA or some high-security facility. But at the vast majority of businesses, it’s needlessly humiliating. So I changed the policy. If we had to let people go, we would treat our departing colleagues well.

At the start, the change affected only individual departures. Then the Great Recession hit and really put my commitment to the test.

Deep cuts

Every industry has their Great Recession story, but publishing took a major hit. At Nelson, sales fell 20 percent in twelve months. The book business doesn’t even have 20 percent margins. So we’re talking about the survival of business here. Layoffs were the only answer.

We had about 650 people on staff. Through three rounds of layoffs, we had to shed 28 percent of the staff, almost 200 people.

And we had let good people go, too. I think of one guy in my church, for example, who I had known for thirty years and who had been with the company for that long. We had to let him go. It wasn’t about his performance—just the economy. But it didn’t make the conversation any easier.

“

I’ve been in leadership for decades now, and there’s no escaping letting people go from time to time.

—MICHAEL HYATT

The only thing that made those hard conversation possible was a good process. I’ll walk you through the five steps we followed and how we used them. In this case, we’re talking about a layoff, but the steps apply to any difficult human resources conversation, including firing an underperforming teammate.

1. Start with the outcome you want

I remember that as we were just going into the recession, I got all of my executive team together. We had all collectively come to the conclusion that we needed to cut our staff. “Look, we love these people,” I said. “We want to treat them with dignity, with compassion, with respect. We certainly don’t want them leaving hating the company or, worse, being left to fend for themselves. What can we do?”

So we started with the outcome we were going for, capturing everything on a whiteboard. “We want these people to feel like they haven’t been abandoned,” we said. “We want people to feel like they’re not alone.” “We don’t want anybody to have any doubt that we’ve gone the extra mile.”

We wanted to give the maximum severance we could. We looked at the table in our employee handbook and doubled it because we were in a position to do that.

We decided that all of those laid off were going to get a phone call from one of the executives in the room. Even though they might have been three or four levels down from us, we were going to call personally and not offer anything other than just to say, “Hey, I want you to know I’m so sorry.” Just to acknowledge it.

We also said this together as a team. “Our mission is not done until these people are all placed in other organizations and have jobs.”

The target outcome was the right place to begin because that gave us our purpose. In everything, we asked, “What leads to that outcome?” The outcome will be different for every organization and every circumstance, but starting with the end in mind (whatever that end may be) is always the right move.

2. Discuss the plan with HR

We discussed the severance plans with people in the human resources department. We did this for many reasons including the fact that it is a legal and liability issue if you don’t have the right processes in place for layoffs. We wanted to make sure we were observing the law to its fullest extent, especially where our older employees were concerned, giving them every consideration.

And more important than legal concerns, we needed to have a plan for what happened once we delivered the news. Where did the conversation go from there? Should we send them to HR? How would we communicate the severance plan? And so on. With those answers in mind, we were able to proceed to our next step.

3. Create a specific set of talking points

If you have one speck of humanity in you, firing people is hard. You don’t want to freeze up or have a meandering conversation with worried employees. It’s critical plan what you’re going to say in advance and make notes on how you might answer questions.

The best way to do this is to have some sort of template so you don’t miss anything and don’t have to do all the thinking on the fly. That makes the next hard step much easier to take.

4. Initiate the conversation

Once we had our outcome in place, consulted HR, and developed talking points, we quickly moved to the next step: calling people to meetings to deliver the bad news.

I encouraged my team to lead with the conclusion, tell them that the decision is final, give the reason, take questions, and let them vent if necessary. You lead with the conclusion because holding them in suspense is cruel and a waste of both of your time. You tell them the decision is final so that they understand that trying to convince you otherwise is a waste of time. You give the reason because people either want to or deserve to know.

In this case, I think it was good for the employees to hear that it wasn’t their fault, that they didn’t do anything to bring this on themselves. It was simply what that the company had to do to survive. And the next step made this all a little more bearable.

5. Follow up with the individual

As part of our first step, we developed a post-termination communications plan to keep in contact with and help our former employees.

Somebody on the team had contact with the people who were let go on a regular basis, and in every case, we asked, “What can we do to help? Can we write letters of recommendation? Can we make phone calls on their behalf?” We did so, regularly, and helped to get many, many people new jobs.

Some people may say that we didn’t have an obligation to do that. Legally, they are correct. But doing right by people matters to a company’s reputation, which can make it easier to attract new talent when the economy recovers. It can also help you sleep a little better at night.

As I said, different situations call for different actions. But whatever the circumstance, following this five-step plan enables you to let people go while treating them with the utmost dignity. Start with your desired outcome, develop a plan with HR, create talking points in advance, initiate the tough talk, and then follow up as necessary.

November 7, 2017

Hobbies of Highly Effective People

How Five Different CEOs Get the Rest and Relaxation They Need

Let’s play a word-association game: Toss out the first several words or phrases that come to mind when you hear the name “Bill Gates.” Don’t overthink it. Just say them out loud or write them down. Ready?

From an informal survey I conducted, some of the terms you might have come up with include: a) computers; b) Microsoft; c) Windows; d) Word; e) Office; f) money; g) rich; h) billionaire; i) Seattle; j) smart; k) nerd; l) coder; or m) charity.

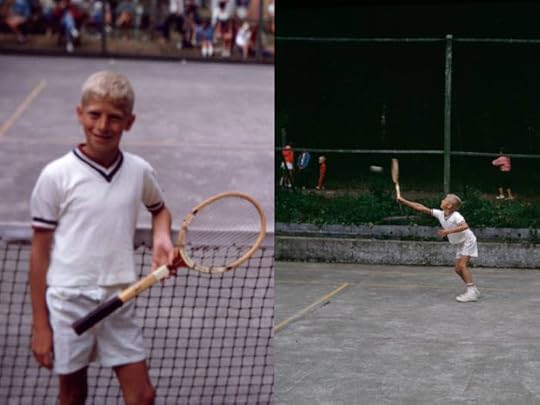

Now, how many of you said “tennis”? If you did, congratulations. You know a part of the Microsoft founder’s life that most people missed. Last year, Gates wrote on Facebook, “I’ve loved tennis ever since I was a kid,” and included the potentially embarrassing youthful pictures to prove it.

In an essay about a book on the game, Gates also admitted that he “gave up tennis when I got fanatical about Microsoft.” He hinted that rediscovering it had helped him to recover some sense of balance in his life. “I am now back on the court at least once a week and have built a pretty solid game,” he bragged.

How solid? This year, he teamed up with tennis great Roger Federer to play doubles in a celebrity charity match against pro John Isner and Pearl Jam guitarist Mike McCready. The four battled in Key Arena in front of sixteen thousand people. Federer and Gates carried the day, but not without some tense moments. “It is hard to describe being on the receiving end of a tennis ball going 123 mph,” Gates admitted.

While the Microsoft founder rediscovered an old method of getting some R&R, many younger CEOs better understand the need throughout their careers. Dick Costolo, who once topped the pecking order at Twitter, has a background in comedy that comes through in interviews and loves to be in the outdoors. He broke his collarbone on a ski trip and was known around the social media company’s offices as an avid beekeeper.

“The whole way the hive works and what’s going on and the crazy stuff that happens as the seasons change, and the way they build and everything, is fascinating. I love just hanging out and watching them,” Costolo told Bloomberg TV. He was known for bringing honey into the office for colleagues, though he teased, “There’s not an infinite supply so some people get it, and some people don’t.”

Costolo’s hobbies aren’t particularly perilous—broken collarbone notwithstanding. But some executives push the envelope much further. Google co-founder Sergey Brin is a daredevil who enjoys roller hockey, springboard diving, gymnastics, and the high-flying trapeze. According to Business Insider, at an annual holiday party Brin once “tried to address party guests from the top of a giant red rubber ball” and lost his balance.

Google Inc. co-founder Sergey Brin bicycling in Mountain View, California

That’s unlikely to happen to Warren Buffett as he pursues his great non-business obsession. The Berkshire Hathaway CEO is so invested in one card game he exaggerated to CBS News, “You know, if I’m playing bridge and a naked woman walks by, I don’t even see her.” Alternately, he mused, “I wouldn’t mind going to jail if I had the right three cell mates, so we could play bridge all the time.”

These pursuits don’t have to be either/or. Buffett’s billionaire peer Gates, for instance, is both enthusiastic about tennis and regularly plays bridge. Yet, given the relentless demands of American business culture today, leaders do have to be intentional about getting away to do just about anything, from hobbies to exercise, even sleeping.

“

Given the relentless demands of business, leaders have to be intentional about getting away to do just about anything.

—JEREMY LOTT

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is one of the most relentlessly competitive leaders you’ll ever encounter. That doesn’t mean he’s burning the midnight oil (even if some of his employees are). “Eight hours of sleep makes a big difference for me, and I try hard to make that a priority. For me, that’s the needed amount to feel energized and excited,” he told Thrive Global.

Bezos even rejects the term “work-life balance” because he doesn’t like the trade-off it implies, saying, “if I’m happy at work, I’m better at home—a better husband and better father.” And a better home life feeds back into work life as well. Amazon’s boss thinks the extra hours of productivity some folks steal by shortchanging their sleep are largely “an illusion” because “quality is more important than quantity” when it comes to making key decisions.

To make great choices, leaders have to have be clearheaded. And the best way to clear their minds is through rest and recreation.

“

To make great choices, leaders have to have be clearheaded. And the best way to clear their minds is through R&R.

—JEREMY LOTT

The lives of these CEOs show there is no set formula. It may take some experimenting to learn what works best for you. And the pursuit may seem annoyingly like goofing off. But we’ve seen how “goofing off” often goes right along with intense focus, drive, and execution. That’s not an accident.

3 Lessons from a Monthlong Sabbatical

How Real Time away Can Recharge Your Spirit and up Your Game

I began my career as a proud workaholic. I measured my contribution by the hours I clocked and the coffee I consumed. So the MH&Co. culture came as a bit of a shock. It was the best kind of shock, though.

With a core value of radical margin and an unlimited PTO policy, our leaders established that this was a different sort of place. There would be no gold stars for weekends worked or midnight oil burned here. Instead, they cast the vision of a sustainably strong team—sharpened by rest and steadied by healthy home lives. It was a radically better path, and I was grateful to walk it.

But just when I thought it couldn’t get any better, Michael and Megan announced a new benefit: A month-long, paid sabbatical every three years. Michael has written extensively about how he benefits from sabbaticals and decided to make that opportunity available to the whole team.

Our heads exploded.

A remarkable opportunity

With my third work anniversary approaching, I was the first employee in line to partake of this glorious benefit. A Florida native, I planned a month of wandering from ocean to ocean: a week on the Gulf in Saint Petersburg, ten days on the Atlantic in Saint Augustine, and a week on the Pacific in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. I figured I’d need a few days at home in Franklin, Tennessee, to conquer the mountain of sandy laundry I knew I’d accumulate.

As the trip approached, everyone asked where I was going, what I’d be doing, and how many books I’d bring. (It was an entire library.) But above all, they wanted to know if I was excited. Of course, I was excited! But to be honest, I was anxious, too. My old workaholic values resurfaced haunting me with unwelcome questions:

What if I couldn’t get everything done before I left?

What if my team resented me for leaving them with a pile of extra work?

What if they decided they could make do without me for good?

How would I ever catch up when I got back?

And, worst of all, would the vacuum left by work leave me feeling lost or insignificant?

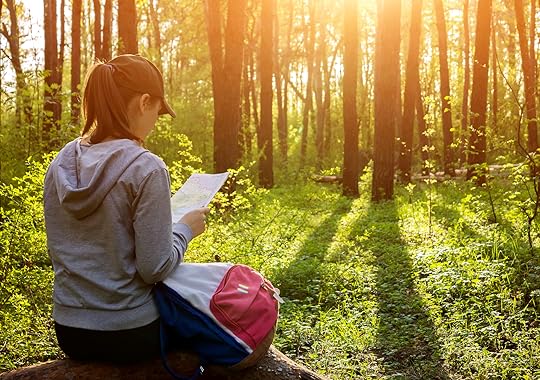

But the ocean was calling, the month arrived, and it was time to go. After setting an away message on my email, deleting Slack from my phone, and reminding my team for the twentieth time that they shouldn’t hesitate to call if it was urgent (they never did), I finally embarked on my grand adventure.

3 findings from my time away

On that adventure, I learned that all those anxieties were unfounded. I learned that when in Mexico you should always order the tortilla soup. And I learned that, for recovering workaholics like me, a sabbatical is truly a lifeline. Here’s why:

First, it amplifies the whispers. A few years back, Pastor Ken Groen shared this revolutionary advice with me: “Urgent things shout, important things whisper. Listen to the whispers.” You know the experience: Something pops up—an unexpected deadline or an angry email from a client—and it somehow drowns out everything else. Urgent things are loud. They shout for your attention and steal focus from more significant priorities.

It’s only when we pause and pay attention that a voice whispers from the stillness: “Maybe you should call your dad.” “It’s a beautiful day for a walk.” “Playing dinosaur toys on the floor with your daughter is the more important thing to do.” “Maybe instead of worrying, you should pause to pray.” In a noisy world, those whispers often escape us. A sabbatical helps still the noise and reconnect us to what matters most.

Second, it reduces the rush. When is the last time you weren’t in a hurry? Really think about it. When? The trouble is that scarcity makes us stingy. When we constantly feel rushed, we become greedy with our time and tend to shortchange those who deserve it most. We start to treat the most important people in our lives like items on a task list. Quality time with a spouse? Check. Weekly phone call with a parent? Check.

A sabbatical turns that around. With all the rushing reduced, I was able to offer my family the rare gift of unpressured time. Some of my favorite moments from the trip were deliciously unhurried: a lazy afternoon visit with my Italian grandmother, listening to her stories; hours in the sand building moats and castles with my adorable nieces; a rambling talk with my sister over glasses of red wine into the wee hours of the morning. A sabbatical allows you to not only hear the whispers but act on them.

Third, it restores the joy. This sabbatical was a wonderful adventure. So it may surprise you that one of the best parts was coming home. True, my gypsy heart adored new flavors and cultures on new shores. It even loved twenty-six straight days of living out of a suitcase. But absence really does make the heart grow fonder.

The time away lent a certain magic to the mundane. It felt like a privilege to be back home, cooking a meal in my own kitchen or using my own washing machine to tackle that mountain of laundry.

That novelty carried over to work, too. After a month away, my creativity was recharged and I felt ready to tackle anything. Reconnecting with my team members was a blast. Even opening Slack gave me a little thrill. Not to mention that my work comes easier (and, according to my team, has gotten better) since I’ve been back. Time away on a sabbatical restores joy to your everyday activities.

It’s possible—and worth it

I’m grateful to work for a company that prioritizes sabbaticals. A month to decompress added more value to my life than I could’ve dreamed. I’m aware it’s a rarity, though. For those who are thinking, “That sounds great, but not all of us work for Michael Hyatt”—I get it. Most corporate cultures aren’t conducive to a whole month away. And for solopreneurs or consultants, time truly equals money.

But before you relegate sabbaticals into the realm of daydreams (right next to winning the lottery or pasta suddenly becoming the world’s healthiest food), let me offer you the same two questions Michael asked us.

First, what would a sabbatical make possible for you? As Michael would say, vision precedes strategy. So dream a bit and imagine what a month of recharging could do for your life and business.

Next, what would have to be true in order for you to take a sabbatical? Would you have to rearrange your consulting schedule or generate a certain amount of revenue? Getting clear on the hurdles is the first step toward conquering them. And if a month still feels impossible, try starting with two weeks.

The bottom line is this: You only have one self. Imagine how much mightier that self would be if you gave it a month to recharge. A sabbatical is possible, and it’s definitely worth it.

Winston Churchill’s Secret Productivity Weapon

How a Midday Nap Can Boost Your Performance all Day Long

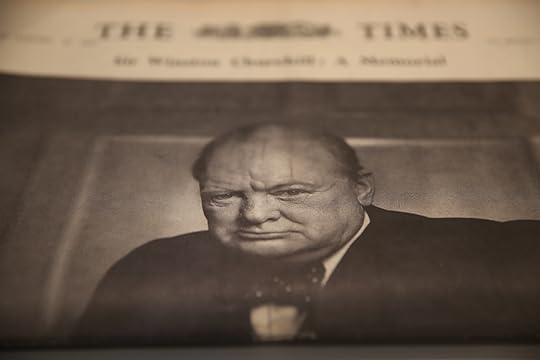

One of the more unlikely museums in London is located in the basement of the Treasury, between 10 Downing Street and the Palace of Westminster: the Churchill War Rooms, the underground complex from which Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his ministers and generals fought World War II.

The War Rooms is a large warren of small offices, dormitories, and dining rooms for the prime minister and his staff, top cabinet officers, and general staff, hidden under a bomb-resistant five-foot-thick, steel-reinforced concrete ceiling. During World War II, hundreds of people worked in them, from clerks and secretaries to generals and ministers. Today, though, the space is dominated by the memory of Churchill.

The exhibits describe the ups and downs of his political career; his indefatigable energy defending Britain and the empire; his eloquence and skill as a writer; his daily life during the war; and his mix of political opportunism, realpolitik, and idealism. But one aspect of his working life gets only a brief mention, at the end of the tour: his habit of taking daily naps.

Churchill himself regarded his midday naps as essential for maintaining his mental balance, renewing his energy, and reviving his spirits. He had gotten into the habit of napping during World War I, when he was First Lord of the Admiralty, and even during the Blitz, Churchill would retire to his private room in the War Rooms after lunch, undress, and sleep for an hour or two. Unless German bombs were falling, he would then head to 10 Downing Street for a bath, change into fresh clothes, and return to work. Churchill’s valet, Frank Sawyers, later recalled, “It was one of the inflexible rules of Mr. Churchill’s daily routine that he should not miss this rest.”

“

Churchill regarded his midday naps as essential for maintaining his mental balance and renewing his energy.

—ALEX SOOJUNG-KIM PANG

Not only did a nap help Churchill keep up his energy, his sangfroid also inspired his cabinet and officers. Napping during boring parliamentary debates was one thing. Going to sleep literally while bombs were falling signaled Churchill’s confidence in his staff and his belief that the dark days would pass.

Churchill wasn’t the only Allied leader to nap regularly. George Marshall advised Dwight Eisenhower to take a daily nap; on the other side of the world, Pacific Command adjusted its schedule around Douglas MacArthur’s afternoon nap, which was part of a daily schedule that “had scarcely changed since his days as superintendent of West Point,” according to his biographer William Manchester. (Adolf Hitler, in contrast, kept more erratic hours at the best of times, and as the Allies closed in on Germany in 1944 and 1945, he tried to stay up for days at a time, powered by a mix of amphetamines, cocaine, and other drugs.)

Winston Churchill has been a model for many leaders, and at least two American presidents were inspired by his example to take up napping. John F. Kennedy was so “impressed by Churchill’s eloquence in praise of the afternoon nap,” said Arthur Schlesinger Jr., that when he entered the Senate he imitated Churchill’s practice of keeping a cot in Parliament. Later at the White House, Kennedy would normally take a 45-minute nap after lunch; like Churchill, he wouldn’t sleep in the office but would head for the residence and change into pajamas. Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, likewise broke up his long day with a nap and shower in the afternoon.

The power of power naps

Why do naps do you good? The most obvious benefit of napping is that it increases alertness and decreases fatigue. A short nap of around twenty minutes boosts your ability to concentrate by giving your body a chance to restore depleted energy. But regular naps—the habit, not just a single nap—have other benefits.

Regular napping can improve memory. Just as the brain uses a good night’s sleep to fix memories, so too does it use naps to consolidate things you’ve just learned. Neuroscientist Sara Mednick found that napping for an hour or more during the day—a nap long enough to allow one to dream—improves performance on memory and perceptual tasks. In a study published in 2003, she had people learn a texture discrimination task in the morning. If you’ve ever been to the eye doctor, you’ve probably had a peripheral vision test: you focus your attention on a light into the center of a large screen and push a button when you see a light on the periphery. Mednick’s test was a bit similar. Subjects were shown a field of little horizontal lines with an L or T in the center. After an irregular interval, some of the lines in the lower left morphed into diagonals. Subjects had to indicate when they saw the change, whether the lines formed a horizontal or vertical row, and what the central fixation target was (partly to keep people from just focusing on the lower left-hand quadrant). It’s a simple test, but this sort of visual discrimination is the kind of thing our brains are designed for, you can quickly get pretty good at it.

After the test, subjects were divided into three groups. One group didn’t nap at all and went about their normal days. The other two took either an hour-long or ninety-minute nap in the afternoon. Everyone was then retested that evening. The subjects who didn’t have a nap did worse on the test. Among the subjects who napped, though, Mednick found that a third had essentially the same scores, while two-thirds did dramatically better in the evening.

“

A short nap boosts your ability to concentrate by giving your body a chance to restore depleted energy.

—ALEX SOOJUNG-KIM PANG

So a nap was helping the brain fix this new pattern-recognizing skill. But what accounted for the two sets of results among the nappers? It wasn’t just the length of the nap: while the ninety-minute nappers were almost all in the high-performance group, people who slept an hour were split between both groups. Medick found the answer when she looked at EEG tracings of their sleeping brains.

When you sleep, you go through a 90-to-110-minute-long cycle that proceeds from light sleep to deep slow-wave sleep and finally to REM sleep. In REM sleep, your eyes twitch (REM stands for “rapid eye movement”), your brain waves pick up again, and you’re more likely to dream. The balance of slow-wave and REM sleep varies depending on when you fall asleep and how tired you are. Some people had fallen into slow-wave sleep during their naps, while others had both slow-wave and REM sleep. The slow-wave sleep group performed the same on the morning and evening tests. The slow-wave and REM sleep group, though, were the high performers. Finally, Mednick had the subjects take the same test again the next morning, and then two days later. Everyone’s scores went up after a night’s sleep, but the nap group’s scores rose more sharply than the non-nap group.

Other researchers have found that even a short nap can improve memory. At the University of Dusseldorf, Olaf Lahl showed two groups of students a list of thirty words for two minutes and told them to memorize as many as possible. One group was then allowed to nap for up to an hour, while the other stayed awake. When they were tested to see how many words they could recall, the students who napped did significantly better than those who didn’t. In a second experiment, one group was kept awake, a second napped as long as they wanted (about twenty-five minutes on average), and a third was woken up after five minutes. Lahl found that even a five-minute nap yielded measurable improvements in retention: not as great as a longer nap, but still statistically significant.

Naps can also help workers avoid mistakes and bad behavior. Jennifer Goldschmied, a graduate student at the University of Michigan, found that naps improve emotional regulation and self-control. She measured her subjects’ levels of tolerance for frustration by giving them paper, a pencil, and a set of diagrams. They had to copy the diagrams without lifting their pencil from the paper or tracing over a line.

What they didn’t know was that half the diagrams couldn’t be copied without violating one of those rules. The participants thought they were being tested on their visual acuity or problem-solving skills, but Goldschmied really wanted to see how much time they would spend trying to come up with a solution before they quit. She found that people who had taken a nap before trying to complete the Frustration Tolerance Task were less likely to give up than those who hadn’t napped, were less impulsive, and were better able to handle frustration.

In separate studies, Dan Ariely and Christopher Barnes found that chronic fatigue or mental exhaustion decreases a person’s self-control and decision-making ability, making them more likely to impulsively cheat than their better-rested colleagues.

How long and when?

Short twenty-minute power naps are good for boosting alertness and mental clarity. But sleep research Sara Mednick argues that by paying attention to what time of day you nap and scheduling longer naps with an eye to your sleep cycle and the highs and lows in your energy and attention levels (which follow an ultradian rhythm, rising and falling repeatedly through the day), you can tailor naps to be more physically restorative, to feed your creative activities, or to improve your memory.

Mednick did some of the first work that scientifically measured the benefits of naps. By the time she started graduate school at Harvard in the late 1990’s, sleep scientists had developed a whole toolkit to study the effects of nocturnal sleep and sleep deprivation on things like memory, alertness, and perception. Mednick applied some of those tools to study naps. Previously, researchers had mainly been interested in naps in the context of shift work and sleep deficits, no one had paid much attention to how naps could affect the cognitive performance or alertness of people with stressful or challenging lives but more regular schedules.

To her surprise, she found that a sixty- or ninety-minute nap provided the same kinds of cognitive improvements seen in people who had slept for eight hours. (That’s not to say you can trade a night’s sleep for an afternoon nap. It doesn’t work that way.) Further, she found that timing your nap can affect the balance of light sleep, REM sleep, and slow-wave sleep, and shape the kinds of benefits you get from it.

Sleep scientists have long observed that our need for sleep is governed by two things: sleep pressure and our body’s twenty-four-hour circadian rhythm. Sleep pressure is the body’s need for sleep, and, under normal circumstances, it’s what’s responsible for our feeling sleepy at night. When you wake up refreshed in the morning, your sleep pressure is at a minimum, and it builds up over the course of the day, until it reaches a peak the next night. Circadian rhythm regulates your alertness level. Under normal circumstances, you reach peak alertness around 8 a.m. and 8 p.m.; your alertness dips a little in the early afternoon, then rises through the rest of the day until late evening.

Circadian rhythm and the sleep pressure cycle operate independently of each other. Under normal circumstances the two are in sync: when we go to bed, our circadian cycle is at its lowest ebb and sleep pressure is high; when we wake up, our circadian cycle is revving up and our sleep pressure is low. But they can be thrown out of sync by jet lag, night shifts, or irregular work schedules.

The interaction of the two cycles helps determine what kind of sleep you get. When sleep pressure is high, your body demands more short-wave sleep. This is one reason why, when you go to bed at night, the first phase of your sleep tends to be dominated by deep, restorative short-wave sleep. As the night progresses, sleep pressure is eased and the need for short-wave sleep declines. In the middle of the night, your circadian cycle hits bottom and then starts to climb upward; as it does, you shift into REM sleep. By the time you wake up, your brain has been getting more active for a couple hours.

Mednick discovered that you can use knowledge of the relationship between sleep pressure, circadian rhythm, and sleep type to tailor a nap to your needs. About six hours after you wake up, your body’s circadian rhythm starts to dip and you’re likely to feel drowsy, especially if you’ve had a busy morning and lunch. A twenty-minute power nap at this point (say at 1:00 p.m.) is enough to give you a mental re-charge without leaving you groggy: if you keep it short, you’ll wake up fairly alert and can quickly get back to work. If you stretch it out to an hour, the balance between your circadian rhythm and sleep pressure will produce a nap that balances REM and short-wave sleep.

If on the other hand, you take a nap an hour earlier, five hours after waking, the balance will be different: more REM sleep, less slow-wave sleep. This kind of nap will deliver a little creative nudge: you’re likely to dream and more likely to enroll your subconscious in whatever you were recently working on. If you wait until an hour later, seven hours after waking, your body needs more rest, and an hour-long nap will be richer in slow-wave sleep and more physically restorative than creatively stimulating.

These aren’t dramatic differences: no nap will consist exclusively of one phase of sleep, and no single nap will magically turn you into Albert Einstein (who did nap regularly, it should be noted). And it’s also important to remember that there’s always a gap between laboratory studies of memory, cognition, and creativity, and real-world creativity and work. Few of us have jobs that require us only to memorize strings of numbers or remember pictures or think up unusual uses for tape. But Sara Mednick’s work on naps helps explain why, throughout history, so many dedicated, obsessed, competitive people have, in the middle of the day, stopped what they were doing and gone to sleep, and why they benefit from it.

A powerful but unused tool

In much of the world today, naps have fallen out of favor. They’re now something that young children do on kindergarten mats, not something for adults, least of all leaders and serious minds. As we move into a world and economy that seems to defy the constraints of geography and time, that operates globally and twenty-four/seven, we feel the need (or pressure) to work continuously, to ignore our body’s clocks and push on even when your bodies are pleading to rest. But this is a mistake.

Naps are powerful tools for recovering our energy and focus. We can even learn to tailor them to give us more of a creative boost, or provide more physical benefit, or explore the ideas that emerge at the boundary between consciousness and sleep. Even during his country’s most desperate hours, when he felt the fate of the nation and civilization hanging in the balance, Churchill found time for a nap. We would be wise to ask if our days and our work are really more urgent.

Adapted excerpt from Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less. by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang. Copyright © 2016. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hidden Stressors that Keep You Working

3 Steps to Finally Make Your Home a Haven Again

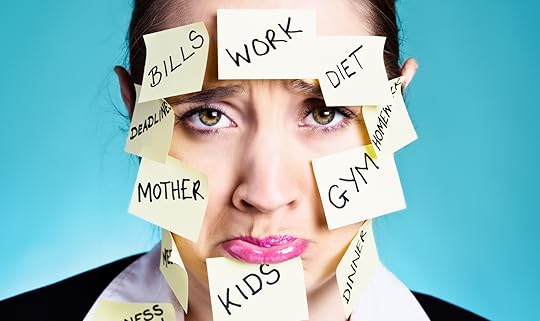

If you are like many Americans, you spend more time working than ever. You’re also more likely to work weekends than in years past. We can blame decades-long efforts by companies to boost productivity (ending a century of declines in work hours) and the evolution of work-at-home arrangements for some of the extra hours. But if we’re honest, there’s more going on here.

Home was once a respite from work. But today it’s often the other way around. We marry later, overschedule our kids, and buy ever-larger homes further away from where we work. To avoid these new stresses, we spend more hours at the keyboard. Hard as it can be, work is easier than family for some of us.

But more work hours will never be a long-term solution. Those inevitable periods of turmoil on the job will only bring more stress to the home. The cycle can leave us feeling trapped, while both our work and home life suffer. What’s the answer? Here are three steps you can take to make home a respite again.

1. Admit things at home are not okay

As Bob Dylan would say, “The times, they are a-changin’.” We marry later, put children into more activities, and have bigger homes than ever. Which means your home life is more-stressful than ever.

Americans marry three to four years older than people did in 1990. Go back further and the gap increases. As a result, we come into our marriages stuck in our ways, making for harder transitions into the togetherness of married life. Later marriage also means later childbearing and related complications. This doesn’t even include the usual ups and downs that come with every marriage.

We who are more affluent also put our children into more extracurricular activities than our parents did a generation ago. This means you are chauffeuring kids from soccer practice to piano lessons, and even helping to coach one of them. Little wonder why 22 percent of parents with kids in three or more activities say their schedules are hectic, compared to just eight percent of parents whose kids partake in one extracurricular or less, according to a 2015 study by the Pew Research Center.

Then there are the household chores, which have grown with our homes. The average home size increased by 1,000 square feet between 1973 and 2015. This means more bathrooms to clean, bigger yards to mow, and more furniture and stuff to clutter the rooms. In short, more anxiety. Especially for women, who still have the traditional housekeeping roles even as they work outside the home, chores have become just another burden on top of being wives and mothers.

You can’t avoid a problem with silence or avoidance. This includes all the stresses at home that can make work seem a respite from family life. Turning it around, starts with talking to your spouse about feeling overwhelmed. They probably feel it too. You should also write down what’s bothering you and why, as well as how you want life to be different.

But don’t stop there. You need to intentionally change how you are living your life.

2. Live your life differently

Only you and your spouse can address all of the issues in your marriage in frank and honest ways. But let me suggest one way to make marriage easier: Spend more time with each other without children (or the technology) and decompress. Grab lunch or skip out for a movie on a weekday while the children are in school, and have a night out once a month just for good measure.

It’s also worth reconsidering the heavy extracurricular schedule. After all, the purpose of those soccer and ballet practices are for them to build their character and help them learn important soft-skills such as teamwork and persistence, not for them to become the next Tom Brady or Misty Copeland.

As for household chores? Let some things go. We should have pride of place, certainly. But that doesn’t mean you should buy it at the price of burnout, or even have to do it all yourself. If your spouse and kids aren’t pitching in, fix that. Another option, depending on your resources, is outsourcing some of the work. And decluttering the house and buying less stuff is also key to reducing your chores; the less you have, the less there is to stress about.

Finally, take some time for yourself. A little rest does the body and mind good. Reading more books can help you relax as well as build your knowledge. You can also take up a hobby that doesn’t involve anything you do for work. Not only do you gain respite from home and work, it can even open up new opportunities for your life long after retirement and the empty nest.

3. Stop using work as your sanctuary

As you make intentional changes to make your home a proper sanctuary, you must also be deliberate in putting work into its proper place.

This starts by spending less time at work. This starts the end of your workday or weekend by organizing a list of priorities for the next as well as thinking through how much time it will really to complete the items on your agenda. Not only does this step help you say no to extraneous tasks that can come during the work day, it even helps you set a limit on how much time you spend on the job.

You should also recognize how stressful work itself can be. From the longer commutes in and out of the office to the long meetings that waste time, recognizing the workplace stresses for what they are will make you want to make home a place of peace.

How to Beat the Burnout Culture

In today’s job world, burnout is a constant threat. Email and smartphones keep us constantly connected. Worse still, we lionize leaders who never rest. Famous CEOs tout 80-hour workweeks and we wear busyness like a badge of honor. Join us to discover the causes of our overwork obsession—and its cure.

October 31, 2017

4 Ways to Get Better at Deferred Gratification

Mindset Shifts for Playing the Long Game

I work with a lot of young people getting started in their careers. Those who chase the highest possible starting salary, most prestigious title, or sexiest-sounding company do worse than those who ignore all of that and focus on value creation, no matter how humble.

You are your best investment. There is no IRA, real estate deal, savings account, or job that will come close to generating the returns you get when you invest in enhancing your own value to yourself and others.

People who realize this look for opportunities to grow and sow seeds for the future. They work for free or low pay to build skill, experience, confidence, and social capital. They can go under the radar in the early years of their career, but three, four, or five years down the road, they are outpacing everyone. Ten years later they’re hiring people who made too many early withdrawals.

There are some famous studies on deferred gratification, showing children with greatest ability to delay payout now for something better later tend to be more successful later in life. We know it works. But that doesn’t make it easy to put into practice. Here are four mindsets that can help us get better at deferred gratification.

1. Find instant gratification in deferred gratification

Have some pride in your persistence. If you can turn the current abstention into a fun game itself, you’ll be much better at it.

You’ve got to have enough sense to be sacrificing with a purpose—meaningless suffering is the worst of all evils. But if you believe that deferring now will make you better and open more opportunities later, do it, and have fun with the pain!

While you don’t want to be annoying and brag about your spartan lifestyle (“I get up earlier than you losers!”), it definitely helps to have a partner or two in the process. Time in the trenches with someone is exhilarating and provides meaning and momentum regardless of the eventual outcome. Find some people to suffer alongside you and push each other.

Anything you can do to enjoy the sacrifices themselves, instead of fixating on the end-result, do it. Every kid knows half the fun of Christmas is the anticipation and restraint to not open gifts early. Besides, if you hate the process, you’re less likely to enjoy the reward.

“

If you hate the process, you’re less likely to enjoy the reward.

—ISAAC MOREHOUSE

2. Leave room for mystery

To avoid suffering without purpose, you need to identify a causal relationship between deferred gratification and something you want more at the end. But don’t get too specific too early.

Rather than, “I want to be making X dollars by Y date,” and deferring now to reach it, try broadening out. Focus on attributes, obstacles, and actions. Ask yourself what attributes increase the probability of making more money, what obstacles prevent you, and what actions you can take every single day to increase the attributes and chip away at the obstacles.

If you’ve got your causality right, the end result can remain open-ended. You know if you do the right actions every day, you will move closer to more influence, impact, and income, but what “more” means, how and when you’ll get there remain unknown. That’s part of the fun!

Focus on the process you know will remove obstacles and build necessary attributes, and you get to be witness to the excitement of your own story as it unpredictably unfolds. Keep doing the work day in day out, and the opportunity explosion can strike when and where you least expect it. Embrace the unknown and take joy in the fact that what you’ll be doing down the road probably doesn’t even exist yet.

3. Have faith in yourself

You can’t well leave room for mystery if you doubt your process. You need faith. C.S. Lewis defined faith not as belief in something in the absence of logic or evidence, but belief in logic and evidence during moments where it’d be easier to abandon it.

In other words, once you’ve mapped out a causal relationship between the pleasures you’re forgoing and the value it will create for you, don’t let doubt creep in when the going gets tough. Take the example of writing. You might say, “I want writing opportunities, which requires improved writing and a larger audience. So, I will commit to blog every day for 60 days.”

There are myriad ways in which the challenge of daily blogging, though an up-front cost, will absolutely move you towards more writing opportunities. The hard part is day 23 when no one’s reading your blog anyway, you have nothing to say, and the little voice in your head innocently asks, “Will you really suffer any harm by skipping today and just relaxing?”

That’s when faith comes in. Forget the moment of confusion and pain. Remind yourself that you were clear-headed at the time you committed, and have faith in your past self. You committed for a reason. Don’t let emotion erode your faith in that reason.

4. Play a different game

I watch a lot of sports. An interesting dynamic occurs frequently. After a play, a player throws a huge celebration and begins trash-talking his opponent. The opponent does nothing. He’s not worried about that one play, he’s thinking about the matchup as a whole. He saves his boasts for the end. “Sure, you blocked my shot once, but by the end, I put 30 points on you.”

Other players ignore the matchup too. “So what, you held me to 10 points. My team won.” Others don’t focus on that either but think in seasons. “You won a game. So what. We made the playoffs.” Others go further. They don’t think about a single season, but a multiyear dynasty. They save their exuberance for truly ascendant achievements.

Finally, some think beyond the sport entirely and engage every play, matchup, game, season, and career as a smaller step in the bigger game of life itself. Some athletes are clearly building for something that will last long after their days on the court or field.

When you suffer short-term depredations, remind yourself that you’re playing a different game. Your friends and peers have cooler toys now. So what? You’re playing a different, far better game.

Why Hopeful Realism Beats Mandatory Optimism

The Downside of Positivity and What It Means for Your Business

One unavoidable piece of advice today is be positive. We’re supposed to filter out supposed negativity in meetings, reports, and general conversation because we think positivity produces the results we want.

Optimism is almost mandatory in some environments. As Dan Lovallo and Daniel Kahneman point out, critical feedback is discouraged and treated like disloyalty. “The bearers of bad news tend to become pariahs, shunned and ignored by other employees,” they say.

If I’m honest, this drives me crazy. Instead of being helpful, compulsory positivity is one of the best ways I know to drift into a crisis.

Swing and miss!

We run several new initiatives each year at Michael Hyatt & Co. Most are successful. But at least once or twice a year we run into a problem. Something is off, and sales trend below projections. It could be the messaging, the offer, even the product—maybe all three!

In the early days that created a lot of anxiety for us. It still creates some. But we treat it differently now. “Okay,” we say, “something’s not working. Let’s dig in and figure it out.” And we usually do. But only because we are willing to acknowledge something isn’t working.

Taking a negative view when things aren’t working enables us to ask better questions. We’re free to raise issues we never would outside a moment of failure. I’m not sure mandatory optimism would let us do that. Instead, we’d keep trusting things would turn around in the end—until they didn’t and we missed our target.

The upside of bad news

When we think about the strategic leadership advantage of self-denial—or better, frustration tolerance—we’re talking about the ability to sit with uncomfortable facts and feelings. Mandatory positivity is the easy out, the supposed quick win that robs us of the benefit that only comes from wading through the difficult realities we face.

Sometimes we forget that you can only optimize something that isn’t already ideal. Recognizing the deficiencies is essential to improving the product. Working on the underside of a goal keeps us from complacency. It propels us toward innovation and creativity in a way that success never would.

When we think of areas like planning or risk management, mandatory optimism becomes positively dangerous. We’ve all encountered people living in a story where it all works out okay in the end. The positive story creates an excuse not to act.

This is when you stop reading your financial statements. You stop checking your bank balances. You stop monitoring the metrics of your business and ignore the people bear all the warnings. “Yeah, yeah, yeah,” you say. “It’ll work out. It’s going to be great.” So, contrary to the story they’re telling themselves, they hit a crisis—or worse—when the right dose of bad news might have saved the day.

The last trait you want in your financial analyst is excessive positivity. You’d hit a rough quarter, run out of cash, and never see it coming. And the crash would be all the worse because you would have missed any chance to course correct when it could have made a difference.

The balance of hopeful realism

The important thing to remember is that both extreme negativity and positivity are mechanisms we use to avoid pain. Extreme negativity is just a way of gaining certainty in the middle of uncertainty. Yes, it’s bad news, but at least you know, and you can reconcile yourself to it. But extreme positivity is the other side of the same coin. Instead of dealing with the difficulties that arise, we avoid looking at them.

Neither optimism nor pessimism works. Instead, we need hopeful realism. Leaders require an accurate picture of the facts, but they also need to have confidence they can overcome even the worst news. That’s realistic. And hopeful.

“

Instead of either optimism or pessimism, we need hopeful realism.

—MEGAN HYATT MILLER

It’s the balance that not only protects you from avoidance but also ensures you retain a sense of agency. As bad as circumstances might be, you’ve got what it takes to make them better.

So back to those MH&Co. initiatives. Hopeful realism has allowed us to see the numbers, recognize we have a problem, and then start working toward a solution. That attitude has freed us to reimagine the messaging on the fly, change an offer, even upgrade the product and positively affect the outcome of the launch.

Ultimately, mandatory optimism is counterproductive. Look at the circumstances. They might just work out alright in the end. But don’t count on it if you refuse to see what’s wrong and take action in the meantime.

How to Say No When it Counts

3 Strategies for Setting Healthy Personal Boundaries

Sometimes you just have to say no. That isn’t always easy. But there are strategies that can help say no when you need to—and save your time, energy, and sanity in the process.

Motivational speaker Byron V. Garrett, my former boss at National PTA, often says that you only have twelve hours a day to take care of business. This means culling away the drive-bys and extraneous requests that can take away from achieving your goals.

Just as importantly, some requests require you to reach way beyond your knowledge and skill set. Certainly, failure is a way of learning. But for those in need of your help, the last thing they need is for you to deliver subpar work.

Of course, this is easier said than done. By nature, we are people-pleasers and we hate to disappoint. When it comes to bosses, saying no can also be career-limiting. Saying no to your close relatives can cause discord in the family. So you will need these three important steps to help you say no—and even end up being helpful to those who make the ask.

1. Organize yourself

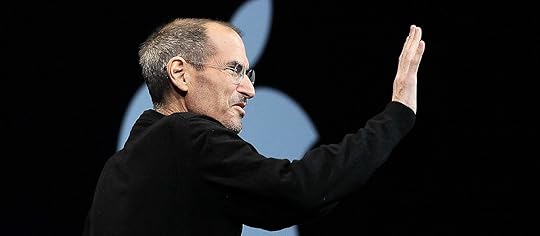

Steve Jobs once said, “People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are.”

When you’re not focused, it is hard to decline other people’s requests. We say yes to anything that looks fun, interesting, or advantageous. To combat this tendency, end your work day by setting up a list of your priorities for the next. This includes reviewing the following day’s schedule and thinking through how much time it will really take to complete what’s on your agenda.

Another way to focus is by setting aside time during the workweek for “office hours” as done by college professors. You can then advise colleagues and others that they can use that hour or so to make requests, seek advice, and discuss options. Limiting your time frame is not only helpful to your business partners, it even helps you gain focus on your priorities.

This can also be done with friends and family. By setting a time when requests can be discussed, you force your brother and best friend to think about how important their request really is—and also empower them to seek out others for help. It also means you get to reclaim your own valuable time.

2. Accept your limitations

We all like to think we are superheroes. But this isn’t anywhere close to the truth. As smart and talented you may be, you must accept your limitations. This means saying no.

Saying yes to a task does no good for friends and family when you are a poor fit for it. Sure, you can look over a home buying contract. But if you have no expertise in real estate law your advice could end up costing them money and time in court. Saying no can be a win-win for both you and the person making the ask.

Career considerations also come into play. As Price M. Cobbs and Judith L. Turnock explain in Cracking the Corporate Code, that new task or position your boss asks you to do can take you off your chosen career path, curtailing opportunities for future advancement. Saying no means staying focused on your achievement.

You may feel guilty about saying no. After all, as high-performing people, we aim to please and hate making excuses. But in accepting your limitations, you are assuaging your angst and also acknowledging that you can’t be all things to all people.

3. Offer alternatives

Keep this in mind, though: Saying no often isn’t enough. You still have to offer solutions that can help family, friends, colleagues, and bosses address their issues.

This starts before you say no by giving thought to the request as well as how you will reject it. Since some people will push back on a simple no, it makes sense to think through a comprehensive-yet-succinct response before giving an answer. Also, be sure to thank the person for making the ask; it is the polite thing to do.

Consultant and author Chris Brogan suggests that you should recommend another colleague within your network or organization to take on a task or role. This move gives the person making the request a new resource while your colleague gains an endorsement of their expertise and work product that they will greatly appreciate and pay forward.

You can also suggest alternative resources and approaches that can actually be more helpful to the person making the request. Because you bring a clear mind to the issue at hand, your suggestions can be incredibly helpful to a harried friend or relative.

Finally, there are some requests to which you cannot (and should not) say no. Your spouse’s honey-do list is one. Your son or daughter’s request for a hug or play time is another. Then there are those times you must be helpful because the world is run on giving each other a hand. Because no is often most powerful when you are willing to say yes to those who need it most.

“

‘No’ is often most powerful when you are willing to say ‘yes’ to those who need it most.

—RISHAWN BIDDLE