Michael Hyatt's Blog, page 49

January 16, 2018

Martin Luther King’s Nobel Cause

The Story Behind Winning the Peace Prize

Martin Luther King’s path to the Nobel Peace Prize took him to several countries and included encounters with J. Edgar Hoover, and the founders of the British civil rights movement. But it began with a Quaker in Philadelphia.

Colin W. Bell, a career charitable worker, wrote the first nominating letter that led to King’s award, the second Nobel Prize for Peace awarded to an African-American. (Diplomat Ralph Bunche received the 1950 prize for negotiations in the Arab-Israeli conflict.)

Bell sounds out Nobel

The British-born Bell had done Friends relief work in Asia and managed a medical unit in China during World War II. At the time he nominated the civil rights legend he was executive secretary of the American Friends Service Committee. The Nobel Foundation includes “directors of peace research institutes and foreign policy institutes” as qualified nominators for the Peace Prize.

“The Board, in reaching its decision, was conscious of the baleful effect of racial tension upon the organization of peace” Bell wrote. “It felt that the work and witness of Martin Luther King, and the spirit in which he promoted ‘the dignity and worth of the human person,’ were influencing the attitudes of great numbers of men and women throughout the world. Until the attitudes epitomized in the life of Martin Luther King were to spread among individual men the nations could not achieve real peace.

“In this respect Martin Luther King’s influence went far beyond the issue of racial tension, and pointed the way to basic new relationships between men everywhere.”

Red crossed

In its full nomination, the American Friends Service Committee played up the international dimension of King’s movement, emphasizing the risks revealed by the Cuban missile crisis and pointing out the potential that leaders of the anti-colonial movement in Africa might adopt non-violence.

But there was a hitch. The Friends nomination was sent in 1963, and the award that year went to the International Committee for the Red Cross. Nobel nominating rules set a February deadline for submissions, and Bell’s letter reached Oslo after the due date.

At the end of the year, Bell renewed his support for King and asked that the nomination be rolled over for 1964, a request the Nobel Foundation granted. King was one of forty-four nominees that year. Among the others were socialist politician Norman Thomas, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, and the Shah of Iran.

Swedes had a dream, too

Much had happened since King’s first nomination. The August 1963 March on Washington focused international attention on the American civil rights movement, and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech took its place in the catalogue of great rhetoric. King also received an important second nomination, this time in a letter signed by eight members of Sweden’s parliament.

“Because of his strong influence,” the Swedish politicians wrote, “he has managed to get his followers to adhere to the principle of nonviolence. Without King’s firm conviction of the rightness and effectiveness of this principle, demonstrations and marches could easily have given way to riot and ended in bloodshed… King has helped establish that not hatred but reconciliation, understanding and respect have become hallmarks for both sides in the fight against racial discrimination.”

The Swedes also pointed up the global dimension of the non-violent civil rights movement. “Dr. Kings’ efforts in the United States can be pattern-forming in the struggle for justice and equality elsewhere in the world,” they wrote, “thus contributing to the resolution of separate conflicts with peaceful means.”

Testing the dream

The year 1964 also brought doubts that non-violence would win the day. A riot broke out in Harlem in mid-July, followed a few days later by one in Rochester, New York. North Philadelphia erupted in late August. The unrest in the three cities resulted in five deaths, hundreds of injuries, and more than 2,000 arrests.

The violence led some observers to question the southern, rural King’s ability to speak for urban blacks. “Martin Luther King can’t reach those people,” novelist James Baldwin said. “I think he knows it.”

The October announcement of his prize came at a low point for King. He had checked into an Atlanta infirmary, pleading exhaustion, when his wife Coretta brought the good news. At thirty-five, the reverend was then the youngest person ever to receive the peace prize.

The journey didn’t end there. Prior to leaving the United States, King had a long, confidential meeting with FBI director Hoover, whom he had long criticized over the Bureau’s civil rights record. On the first leg of his trip to Oslo, King stopped in London and spoke at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Malcolm X, King’s ideological opposite in the Civil Rights movement, was in London at the time, and in his public statements King minimized the appeal of militancy and separatism.

“Negroes in the United States are more in line with the philosophy of integration and togetherness, and not in line with racial separation,” he told reporters. King’s most consequential encounter in Blighty was with a small group of local activists at the Hilton, who went on to found the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, Britain’s first modern civil rights organization.

King’s “renewed dedication”

King had fewer than four years to live when he received his Nobel Peace Prize. Bell continued his work for the Friends until the late sixties and died in 1985. In his acceptance speech, King placed his own prize in the context of a mass movement with millions of unknown activists.

“Today I come to Oslo as a trustee, inspired and with renewed dedication to humanity,” King said. “I accept this prize on behalf of all men who love peace and brotherhood. I say I come as a trustee, for in the depths of my heart I am aware that this prize is much more than an honor to me personally.”

Hiring Diversity Makes You Smarter

How Your Organization Can Thrive by Gathering a Team of Rivals

“How could we have been so stupid?” The question was posed by none other than John F. Kennedy in the aftermath of the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco, the a failed invasion of Cuba by CIA-backed Cuban exiles. The disastrous plan, strongly recommended by top advisors and approved the President himself, resulted in over three hundred deaths, including those of five Americans.

Interestingly, key decision makers included four graduates of Harvard and one each from Oxford, Yale, Princeton, and the University of California, Berkeley. So how did some of the brightest minds of the twentieth century make one its worst decisions?

In a word, groupthink. That’s the conclusion drawn by psychologist Irving L. Janis, who studied that question and coined the term. Groupthink is the tendency of group members to over-value conformity and acceptance by the team. It produces “a deterioration in mental efficiency, reality testing and moral judgments as a result of group pressures.” In homogeneous teams, loyalty and conformity become an impediment to sound thinking.

The solution? Diversity. Janis concluded that group members must deliberately seek outside opinions and other ways of thinking about a problem. It’s impossible to make a good decision in an echo chamber.

“

It’s impossible to make a good decision in an echo chamber.

—LAWRENCE W. WILSON

It’s even harder to create a thriving company in one. A growing number of experts agree that creating a heterogeneous workforce is not merely matter of fairness; it’s the best way to produce innovation. To go further faster, you need a diverse team.

The danger of affinity bias

To be sure, assembling people with significant differences presents difficulties as well as rewards. According to Gillian Coote Martin, diversity can produce dysfunctional conflicts, lost productivity, and difficulty achieving harmony in group settings.

That may explain our instinctive reliance on what researchers call affinity bias, the tendency to prefer working with people similar to ourselves. It’s no surprise that Kennedy’s inner circle was heavily weighted with Ivy League products.

But affinity bias is the Petri dish in which groupthink thrives. Imitation quickly replaces innovation, and routines become sacred rituals. Teams that are too much alike have a harder time finding new approaches to a problem.

To counteract this effect, Scott Page, author of The Diversity Bonus, advises cognitive diversity. According to Page, when businesses intentionally recruit people with diverse intellectual skills, they earn a bonus in increased problem solving, creativity, and innovation. Diverse teams simply perform better.

Cognitive diversity refers to the differences in how we think, including such things as our education, task activation, and approaches to decision making. While such things may be influenced by one’s identity—race, ethnicity, age, ability, language, nationality, socioeconomic status, gender, and religion—cognitive diversity is something more. It is about how we interpret information, reason, and solve problems.

Cognitive diversity multiplies, rather than adds, the skills of a team.

One plus one is three

Imagine that Kyle is starting rock duo in his garage. Kyle plays guitar, drums, and bass. His classmate Tyler also loves rock music and plays guitar and drums. But Ariel, who attends a different school, plays keyboards and is a talented jazz singer.

If Kyle and Tyler form a band, they’ll have a lot in common. But they’ll also be limited musically, since Tyler adds no skills that Kyle doesn’t already have. If Kyle teams with Ariel, he’ll have to accept their differences in gender, education, and musical training. But Ariel would multiply the possible musical combinations. That’s the diversity bonus.

“

To go further faster, you need a cognitively diverse team.

—LAWRENCE W. WILSON

Now imagine that bonus applied to the knowledge-based workplace, where complex, non-routine, cognitive tasks and group problem-solving are the keys to success. Teams that include activators as well as information-gatherers, achievers as well as communicators, both innovators and systems-thinkers, are bound to produce better results than will teams of identical minds.

Which would be more effective in designing a new mobile app: a team of all engineers, or a team comprising two engineers, a marketer, a data analyst, and a designer? Diverse teams are by nature more innovative, and a growing body of research confirms it.

Researchers recently identified a direct link between a company’s level of workplace diversity and its ability to innovate. According to Roger C. Mayer, Richard S. Warr, and Jing Zhao, firms with a more varied workforce produced more new products per dollar spent on R&D than did their less-diverse counterparts. Diversity makes for more efficient use of salary dollars.

The trio concluded that pro-diversity practices increase the potential pool from which a firm is able to recruit talented and creative employees. Further, they assert that having a wider range of views, backgrounds, and expertise helps with innovative problem solving, especially during a recession. This is the diversity bonus in action.

A fight for innovation

Carla Harris, vice chairman, managing director, and senior client adviser at Morgan Stanley agrees that hiring diversity is key to success. She says that to be competitive, companies must start by having “a lot of different people in the room.”

She adds, “We are in a fight around innovation everywhere around the globe in every industry, and the only way that you are going to get the very best ideas that will allow you to lead is to make sure you’re getting equity around contributions from all of your people.”

“

The secret to innovation is to add new ways of thinking, approaches to problem solving, and points of view to your team.

—LAWRENCE W. WILSON

One way to do that is to correct the understandable but profound error of giving in to affinity bias. A team of Ivy-Leaguers is not necessarily better than a team of community college grads. The secret to innovation is to add new ways of thinking, approaches to problem solving, and points of view to your team. Hire diversity for a competitive edge.

What Martin Luther King Jr. Teaches Leaders Today

5 Transformative Principles for Change

Seeking a working definition of leadership is one thing, but seeking examples of defining leaders can be more valuable. We embrace the familiar adage, “more is caught than taught,” because many of us are visual learners. We have to see leadership in action and not just read about it or talk about it. Defining leaders are men and women who have a knack for doing what is right. They also do what they say and they say what they do. Words and deeds must match up for a leader—and when they do, you will have a change agent to contend with.

This is why so many people consider Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to be one of the most defining leaders of his time, or anytime for that matter. This Baptist minister, hailing from Atlanta, Georgia, walked the talk and talked the walk when it came to engaging America in the quest for civil rights through nonviolent passive resistance.

Consider how these five timeless principles of leadership, which Dr. King exemplified, are able to span generations and how they can be applied by any person in any organization. Following Dr. King’s example, we must:

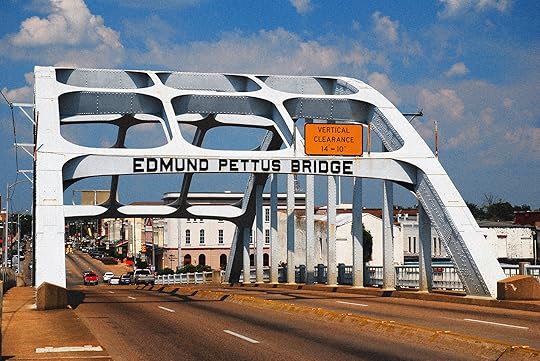

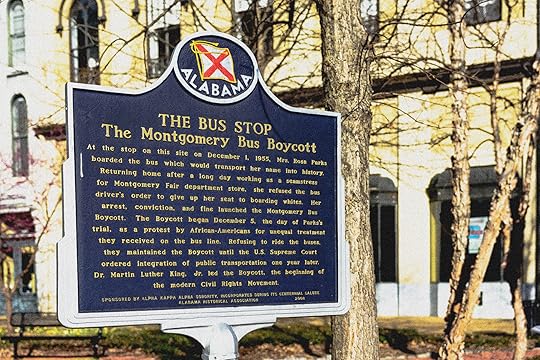

1. Be prepared for our moment

Martin Luther King grew up in a home where education and community involvement were highly prioritized. While concluding his doctoral studies, he accepted the pastorate of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. From this small church, a twenty-six-year-old King was thrust onto the national stage to lead the historic Montgomery Bus Boycott. The older ministers in the city found King to be the most qualified candidate to lead the burgeoning movement. It’s been said that success happens when preparation meets opportunity, and since none of us know specifically when a life-changing opportunity will present itself, it would behoove us all to be ready.

Being prepared for your moment allows you to be spontaneous without being sloppy. When what was arguably Dr. King’s personal apex during his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, he deviated from his written notes when Mahalia Jackson beckoned for him to tell America about the dream he had. For a person to speak extemporaneously as King did at that pivotal moment in history, and to do so with ease and excellence speaks to how well prepared he actually was. Apparently, that speech never had an official title, but once he finished climbing to heights of unmatched oratorical prowess, everyone knew what to call it.

“

Being prepared for your moment allows you to be spontaneous without being sloppy.

—CHRIS WILLIAMSON

2. Be willing to work in collaboration

Although Dr. King and Rosa Parks were the most well-known faces of the civil rights movement, Dr. King knew that he could not be successful on his own. It took thousands of ordinary people working in the trenches to see redemptive social change occur in our country. King was known to confide in his inner circle of fellow clergy and friends before launching out with new initiatives. He understood that a plan works best when many people get to weigh in on the plan.

When King’s efforts hit a roadblock in Birmingham, he and his cohort knew they needed considerable wisdom to overcome Bull Connor’s tactics of resistance. At this point, one of King’s aides suggested that they incorporate children into the protests. King listened to the idea and agreed to implement it. As the world watched fire hoses and police dogs turned lose on the protestors and their children, America suddenly developed a conscience it had never had before. By working collaboratively, segregation would soon be dethroned in Birmingham.

3. Be a person of courage and conviction

Martin Luther King once said, “If a man has not discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.” Even though King’s feet were made of clay, he somehow found the courage to keep marching on in spite of the house bombings, multiple arrests, and daily death threats. By watching Dr. King, we see that courage is not the absence of the fear. Rather, courage is the capacity to accomplish what is necessary in spite of your fears.

King once said that a leader must know when to be a consensus leader and when to act on conviction. As mentioned earlier, collaboration is a prerequisite to successful leadership, but there will come a time when a leader will have to act on an internal conviction that others will not have, agree with, or understand. When King decided to incorporate non-violent methodology into the philosophy of the movement, many black people during that time thought he was being a coward.

When King mustered the courage and conviction to speak out against the war in Vietnam, many Americans thought he had crossed the line. From King, we discover that brave leaders are willing to stand alone if they have to, as long as they believe in their heart of hearts that God is standing with them.

4. Be globally minded

Beyond traveling extensively to countries such as India, South Africa, Ghana, and Israel, Dr. King also traveled to Oslo, Norway in 1964 to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. In his acceptance speech, King said, “Negroes of the United States, following the people of India, have demonstrated that nonviolence is not sterile passivity, but a powerful moral force which makes for social change.” Any student of Martin Luther King Jr. knows that he learned the methods of nonviolent passive resistance from the teachings of Jesus Christ and the example of Mahatma Gandhi.

“

By watching Dr. King, we see that courage is not the absence of the fear. Rather, courage is the capacity to accomplish what is necessary in spite of your fears.

—CHRIS WILLIAMSON

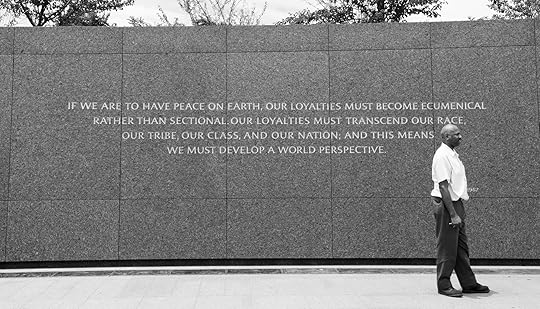

King went on to say in that speech, “Sooner or later all the people of the world will have to discover a way to live together in peace, and thereby transform this pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood.”

King was not afraid to turn his local pulpit into a global one, especially concerning his opposition to the Vietnam War. King once preached, “We are taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them 8,000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in Southwest Georgia and East Harlem.” King reminds us that the most effective leaders have their eye on the local scene as well as the world stage.

5. Be a servant-leader

In its January 1964 issue, Time magazine named Dr. King, “Man of the Year” based on his efforts in 1963 of helping to dismantle segregation in the south. By the time of his death, Dr. King received hundreds of awards for his work in civil rights, but in spite of all of his accomplishments, he never stopped reaching out to disenfranchised people. Few leaders will continue reaching downward as they find themselves rising upward. No wonder Jesus saw the need to teach that the greatest among us should be servants (Matthew 23:11).

Like Jesus, servant-leaders are intentional to incarnate into the impoverished world of the underserved. While consistently making the journey to live in community with the weak, the servant-leader knows that he or she will gain far more than he or she can ever give. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968, he went to that divided city in order to stand up with and for striking sanitation workers.

America’s “Dreamer” and the Time “Man of the Year” died serving poor people who had to fight for their dignity by protesting with signs reading, “I Am A Man.” Would you have gone to Memphis? Would you have traveled without police protection and stayed at a meager motel even when you knew your life was in danger? Servant-leaders stay on mission because they place the needs of others above their own. A great book to see King’s servant leadership qualities put in motion can be found in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.

We all know that words have power, but words put into action have even more of a capacity to change hearts, minds, and unjust systems. Being a definitive leader will not always be easy. In fact, it will always be costly. But Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. shows us that it will always be worth it.

How MLK Responded to Failure

Lessons Learned from a Failed Campaign

Martin Luther King Jr. had many successes in his life. His first desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia, wasn’t one of them.

It started in late 1961. Local and national black groups had been trying to desegregate the city’s parks, bus facilities, and businesses. So far, they had racked up many arrests and fines through protests and non-violent resistance. But they had made zero political progress with their demands against the city’s stubbornly segregationist government and police force.

A local doctor appealed directly to King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference to get involved. King felt he must, explaining, “I can’t stand idly by while hundreds of negroes are being falsely arrested simply because they want to be free.”

King got in a car and made the 180-mile trip from Atlanta to Albany. All he lacked was “a toothbrush, an overnight bag, or any prepared strategy,” writes Donald Phillips in Martin Luther King, Jr., on Leadership.

What could possibly go wrong?

Just about everything that can go wrong with a protest campaign went wrong in Albany. The black leadership was divided along young and old, local and national, and other lines. The local, pro-segregationist city hall and police force were wiley and press-savvy. And King was utterly unprepared to manage the situation.

True to form, King came to the city; made a rousing speech at Shiloh Baptist Church on December 15 to local, mostly black supporters (“How long will justice be crucified, and truth buried?!”); led a march through downtown Albany; and was arrested.

From there, King lost the plot. He expected to spend Christmas in jail and invited thousands of others to join him. City Hall understood this would only overload the prison to the point of bursting and create a national cause celebre, so they got creative.

City leaders entered into talks with the non-jailed black leaders and made a deal that was heavily stacked in their own favor. All protests would cease for thirty days, jailed persons were released without bail, and there was talk of a biracial committee to address problems. However, the civil rights leadership would have to take this on a handshake as Albany Mayor Asa Kelley refused to put anything in writing.

King didn’t like the agreement because he didn’t think it moved the ball forward on desegregation. But he felt bound to honor it and not grandstand. He preached again at Shiloh Baptist, went home to Atlanta, and monitored the situation hoping for the best. Not long after he left town, the agreement proved to be not worth the paper it wasn’t printed on. With the pressure off, Albany officials let it be known they wouldn’t budge one inch on segregation.

Round two, what’s King to do?

This was intolerable to many of Albany’s blacks, who made up about half of the city’s population. They boycotted several businesses, started a carpool program to circumvent the segregated city busses, held sit-ins, and did small marches and intermittent picketing.

The stage was set for King to come back and make a real impact, but he was again frustrated. In mid-July of 1962, he was summoned back to Albany along with SCLC treasurer Ralph Abernathy to face charges related to the December protest. They were found guilty and given a fine of $178 or forty-five days in jail. King and colleague chose jail, and prepared to use that sentence to shine a light on Albany’s system of unjust segregation.

After one day in the clink, Police Chief Laurie Pritchett released King and colleague, offering up the excuse that an anonymous benefactor had paid their fines. This wrong-footed King, who complained that he did “not appreciate the subtle and conniving tactics used to get us out of jail.”

Back on the outside, King and his supporters hastily tried to organize another grand protest. This was met with a restraining order by a federal judge. King felt that a federal court order ought to be obeyed, and thus delayed the march while civil rights lawyers worked to overturn the order.

That cancellation, in turn, set off a wave of recriminations in Albany’s divided black leadership. Most of the student wing no longer wanted to protest. “Other local black leaders,” writes Phillips, “also became so disenchanted that they actually made an offer to Chief Pritchett that, in return for talks, Martin Luther King would leave town and go back to Atlanta.”

Learning from the chaos

Honestly, King might have been better to go back home for what happened when his lawyers managed to overturn the restraining order. Local cops commenced the usual arrests. Several frustrated young marchers started chucking rocks at police.

These projectiles caused serious injury and called the movement’s bedrock commitment to peaceful protest—a vital part of seizing the moral high ground and calling for redress—into question. Police Chief Pritchett pounced, savaging King and company in the press for those “nonviolent rocks.”

The whole Albany experience was a fiasco and a failure. But it was a failure that King learned from, and not just after the fact. In the days following the violent protest, he visited several local black pool halls and talked with the youths at length about the importance of non-violence to the success of their movement. Violence was the way of the KKK and lawless law enforcement. King’s people would only win, ultimately, by insisting on a better way.

“

Violence was the way of the KKK and lawless law enforcement. King’s people would only win, ultimately, by insisting on a better way.

—JEREMY LOTT

From the ashes of the Albany campaign, King’s SCLC came up with a four-pronged template or strategy for ending segregation that included direct action, lawsuits, boycotts, and voter registration. These helped African-Americans to increase their voice and leverage their clout, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

When King came to Albany, he was riding high on past successes. He left the city not blind to his movement’s failure there. But he also left convinced they could learn from the setback and use it to build something more durable and beautiful going forward. And they did.

5 Leadership Lessons from Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King’s efforts initiated changes that would transform American society. That’s why the nation celebrates Martin Luther King Day on the third Monday of every January. It’s a chance to reflect on what he meant for the nation—and what made his leadership so successful. In this episode, we’re going to explore the leadership legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.

January 2, 2018

5 Reasons Resolutions Fail

Why They Don’t Work and What You Should Do Instead

Millions of Americans admit to making New Year’s resolutions. Most of us can stick it out a few weeks, but fewer than half are still going after six months. Less than 10 percent are ultimately successful. In this episode, we’re going to explore five reasons resolutions commonly fail—and what you can do to finally gain ground in the upcoming year.

Your Best Year Ever, Without the Resolutions

My New Book Can Set You up for Success in 2018

If you are late to the game in making your New Year’s resolutions, I have an idea for you: Don’t do it. New Year’s resolutions may be as old as the Babylonian empire, but that doesn’t mean they are very effective. Millions of Americans make New Year’s resolutions every year, but research says most of us are wildly unsuccessful.

Many of us only stick it out for a while. A quarter bomb in the first week. A third don’t make it past the first month. Fewer than half are still plugging away after six months. Fewer than 10 percent of us are actually successful.

Why it matters

Some industries, such as fitness centers, count on our failure and build that into their business models. But this is about much more than numbers. It’s about people’s dreams. Here were the top-ten resolutions people set for 2017, according to Statistic Brain:

Lose weight and eat better

Make better financial decisions

Quit smoking

Do more exciting things

Spend more time with friends and family

Work out more

Learn something new on my own

Do good deeds for others

Find the love of my life

Find a better job

Our resolutions concern our health, wealth, relationships, and personal development. In other words, they’re about the things that matter most to us.

I’m sure you have your own personal stories of starting the New Year strong only to get busy, fall behind, and eventually lose motivation. It’s happened to me. And it’s exactly why I don’t bother making New Year’s resolutions anymore—at least not the usual kind. When I think of my health, my family, my spiritual life, and my business, I know some dreams are just too important to entrust to a faulty system.

Make resolutions that actually stick

Instead, I utilize a proven goal-setting process that incorporates safeguards for many of the pitfalls and failings of typical resolutions. It’s taken me years to develop this process, and I’ve seen it work not only in my own life, but also in the lives of countless people with whom I’ve shared it.

Some people will say that the best way to make our resolutions stick is to only pick one or two for the year. But that’s leaving far too much on the table for me—and probably a lot of you, too. We’re talking about the things that matter most, right? Why leave so many things undone and miss so many opportunities to grow? Instead of cutting back, we just need to use a system that actually works.

An effective goal-setting system must factor at least five dimensions of goal-attainment:

1. Genuine possibility. Unless we believe we can reach our goals, we’re sure to miss. The number of people in their twenties who achieve their resolutions is far greater than those over fifty (39 percent to 14 percent). Why? The greater the number of setbacks we’ve experienced in life the less likely we are to believe we can prevail. Doubt is a goal-toxin. To reach our goals, we need to trade these limiting beliefs for liberating truths.

“

To reach our goals, we need to trade our limiting beliefs for liberating truths.

—MICHAEL HYATT

2. Past experience. Dragging the worst of the past into the best of the future is another reason our resolutions fail. If we get closure on the past, especially those efforts that went unregarded or unrewarded, we’re able to more confidently step into the future. The trick is to get honest about:

what we wanted to happen

what actually happened

why it happened, and…

what we can change in our approach going forward

3. Effective design. Part of the problem with typical New Year’s resolutions is that they’re poorly designed. “Lose weight” or “Make better financial decisions” fail on several counts. Among other things, effective goals are specific and measurable. Goals poorly formulated are goals easily forgotten.

4. Intrinsic motivation. Another major reason resolutions fail is that we’re not motivated enough to attain them. Without a compelling reason to persist, we lose interest, get distracted, or forget what we purposed to do. As my wife Gail says, “People lose their way when they lose their why.”

“

People lose their way when they lose their why.

—GAIL HYATT

5. Proven tactics. Finally, resolutions fail because we’re missing proven implementation tactics. Winning a battle takes both strategy and tactics. But unless someone shows us what works best for attaining our goals, we’re left to luck or hard knocks. No wonder it sometimes takes us five or six years in a row to finally achieve an important resolution.

Help is on the way

Life’s too short for typical New Year’s resolutions almost guaranteed to fail. The good news is that you can shortcut the hard knocks, stop counting on luck, and finally succeed.

Life’s too short for typical New Year’s resolutions almost guaranteed to fail. The good news is that you can shortcut the hard knocks, stop counting on luck, and finally succeed.

My new book Your Best Year Ever comes out today. Based on the proven goal-setting process I already mentioned, it’s specifically designed to address these five dimensions of goal-attainment. Depending on how important your resolutions are to you, this could be the most important book of the new year for you. Ask yourself: What would my life look like twelve months from now if I reached my most important goals?

Order Your Best Year Ever now and you can leverage my proven system for yourself. You’ll discover how to overcome your past setbacks, design goals that actually work, and achieve more than you thought possible in 2018. And if you buy this week, you can get over three-hundred dollars’ worth of free bonuses. Check it out here.

The Secret Power of Wasting Time

One New Year's Resolution That Probably Saved My Life

Studies show that most New Year’s resolutions flop a month or less after we make them. Gyms all over the country are banking on it. They have far less capacity than the year-round passes they sell to strivers who begin the year intent on changing their shape, but who give up after a few weeks of bobbling barbells and chasing treadmills.

And yet, I still believe in New Year’s resolutions because one of them likely saved my life.

Trapped in DC

This was back in 2009. I had moved to Washington, DC, seven years prior and had worked for several magazines and think tanks. I was good at what I did, but it wasn’t enough.

As a kid, the thing I had most wanted to be was an adult. It seemed the best way to do that was through a monomaniacal pursuit of “adult” things. So I fastened onto politics and policy, found something to say, and went to our nation’s capital to help say these things to the folks in power.

It was a bad fit, almost from the start. The weather in and around DC is awful, and the social scene is saturated with booze and regret. Ambitious people go there to make a difference. They usually end up frustrated by gridlock and shackled down by golden handcuffs. They can make a good deal of money off their knowledge and connections if they opt to stay in DC, but in the rest of the country, it’s a harder sell.

Over the course of seven years, I started to move home to Washington state several times. Every time, some DC outfit came calling with another job offer. Lacking a solid anchor, I’d go back. This situation in life made me miserable, and I drank a punishing amount to cope.

Non-marching orders

The sticking point came was when I finally stopped blaming the place and looked squarely at myself in the mirror. The problem wasn’t really DC. It was me. Even when I went home, I was miserable—in learning to succeed, I had never really figured out how to live.

Pleasures that normal people enjoyed I wrote off as pointless distractions. As the year came to an end, I wondered how, or even if, one could go about fixing this. And as if in answer to prayer, a three-word resolution came to me.

“Waste more time.” These were words I badly needed to hear and repeat. The resolution was too short to forget, too pungent to ignore, too much of a stretch to allow easy rationalizing. It was time to stop and pick the blackberries rather than type furiously on them. This resolution gave me permission to take what I would have mocked as “frivolous” living seriously.

“

“Waste more time.” These were words I badly needed to hear and repeat.

—JEREMY LOTT

Start your engines

Here are some ways the resolution played out over the next year:

Helped a friend move from Fairfax, Virginia, to Seattle, Washington, in his turbocharged Jetta TDI in just under three days.

Made it to Seattle in time for Mother’s Day lunch.

Turned another trip home to celebrate the kid brother’s birthday into a permanent change of residence.

Finally landed a job based outside of DC that offered remote work.

Put 12,000 miles on my own car with trips to Seattle, Portland, Canada, as well as many joyrides around Whatcom and neighboring Skagit Counties.

Rode in a helicopter.

Spelunked through underground caves.

Went to motocross races.

Rediscovered my love of baseball and comic books.

These are things that I would never have made time for in the past. In many cases, I hesitated before saying yes. And every time those three words functioned as a battering ram on misplaced pride and inhibitions.

“

In learning to succeed, I had never really figured out how to live.

—JEREMY LOTT

Work hard, play free

You might suppose all this wasted time made for less work output, though that’s far from clear. That same year, I finished and saw two books published, helped to launch and maintain two new websites, wrote a number of articles and speeches, and did media hits to promote all of the above.

I accomplished all that because “waste more time” wasn’t about slacking off. It was about carving out a life that had room for more than just work and striving. For the first time in a long time, I felt truly free.

Maybe I have just described a situation that is not so far from your own. Maybe you feel like you’ve been stuck for a long time and, as we wade into this New Year, you wonder what you might do about it. If you think my three words could help you, by all means, take them. Repeat them to yourself out loud. See if they fit. And, yes, it’s okay to start with a whisper.

From Babylon to Self-Betterment

A Quick History of the New Year’s Resolution

Are you making a New Year’s resolution this year? It’s quite likely you are, as surveys conducted in recent years show that something like 40 percent of Americans make one annually. And what are they resolving?

Last year’s Marist study, the annual gold standard of New Year’s resolutionology, showed that their number one goal was—good news, fellow citizens!—”being a better person,” beating out the evergreen weight loss for the top spot.

The American public’s endearing, if slightly loopy, resolve to be better people may lack specificity, or what the project managers in your life would call “deliverables,” but it does harken back somewhat to the original spirit of New Year’s Resolution making.

While most New Year’s resolutions of today are, like our modern society more broadly, typically individualistic and self-interested, the custom has more often been about affirming transcendent or pro-social values.

“

While most New Year’s resolutions of today are typically individualistic, the custom has more often been about affirming transcendent or pro-social values.

—EVAN MCELRAVY

Planned in Babylon

New Year’s resolutions have played an intermittent role in the development of Western Civilization. They appear first four thousand years ago in the annals of Mesopotamia, where the Babylonians marked their New Year (called “Akitu”—try to remember that for your pub quiz) with twelve days of religious pageantry celebrating the spring barley harvest and the greatness of Marduk, the patron god of Babylon.

A highlight of the festival came on the fourth day when the King of Babylon was paraded to Marduk’s temple before the people of the city. There its high priest, dressed in the guise of the deity, would carry out a ritual humiliation, stripping his royal majesty of his official garb, slapping him twice on the face very hard, and obliging him to prostrate himself before the altar and recite a lengthy list of promises and resolutions to the god and the state for action in the coming year.

And yet, New Year’s resolutions were not just a matter for the peak of Babylonian society. The common people also made promises to the gods and their fellow subjects, resolving, for instance, to pay off debts. Carrying out these resolutions faithfully would ensure the good graces of Marduk and his pals in the coming year. Breaking them could lead to a catastrophic withdrawal of divine favor. Consider that when you’re contemplating letting your gym membership lapse this February.

The Roman reset

The starting of each new year on January 1 began, according to tradition, in 45 B.C., when the Roman state adopted the Julian calendar. It was named after Caesar, who commissioned it, but actually worked out by an Alexandrian Greek named Sosigenes, who can be seen portrayed by Hume Cronyn in the Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton film Cleopatra.

In fact, New Year’s Day had been the first of January previously, in a tradition attributed to the mythic Roman king Numa Pompilius. Alas, from Numa’s day to Caesar’s the Roman calendar fell into a state of utterly bewildering disarray. The start of the New Year fell generally, but not always, in March, while lengths of months, the order of months, number of months, really everything, operated on a distressingly ad hoc basis. Eventually, nothing else would do but the sort of radical rethink you really need a proper dictator to push through.

Numa’s reasoning—and Caesar’s—was that the eponymous divinity of January (the two-headed Janus, god of doors, gates, and bridges, as well as beginnings, endings, and transitions of all kinds) had a logical ritual connection to the New Year. So on that day Romans would conduct special sacrifices to him and, yes, make promises of good and proper behavior in the year to come. As in Babylonia, these resolutions touched both the state and the civil society, as the start of the New Year also meant the taking of the oaths of office of that year’s elected officials.

Over the period from the collapse of Rome down to the start of the modern era, the tradition of making New Year’s resolutions seems to have died out, or at least down. Already in the late years of the empire, lusty pagan New Year’s celebrations and vows to Janus were giving way to Christian austerity of the Feast of the Circumcision.

With the breakdown of central authority, the calendar also fell into disunity. During the Middle Ages, New Year’s Day varied by country. Depending on where you lived, it might have been September 1, the winter solstice, Christmas, January 1, or the spring equinox.

Promises to peacocks

The main upholders of something like New Year’s resolutions down through those centuries seem to have been the Jews, with their ten days of repentance and reflection between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. But there is at least one interesting Christian custom from the period. At the height of the Age of Chivalry, knights are supposed to have marked the New Year with the so-called Voeux du Paon, Peacock Vows, affirming their commitment to the chivalric code of conduct.

In the vivid description of Charles Dickens, “It was on the day when a solemn vow was made that the Peacock … became the great object of admiration, and whether it appeared at the banquet given on these occasions roasted or in its natural state, it always wore its full plumage, and was brought in with great pomp by a bevy of ladies, in a large vessel of gold or silver, before all the assembled chivalry.”

The peacock, said Dickens, “was presented to each in turn, and each made his vow to the bird, after which it was set upon a table to be divided amongst all present, and the skill of the carver consisted in the apportionment of a slice to everyone.”

Regrowing resolve

The modern era of New Year’s resolutions seems to have begun with nonconformist Protestantism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Puritans were encouraged to lay off the ale and spend New Year’s Eve in sober contemplation of the year to come, and John Wesley instituted the Watch Night or Covenant Renewal services still practiced in some Methodist churches.

The history of the tradition from that time to now, however, has been one of growing popularity and a more personal focus. Compared to the 40-something percent of Americans who make one today, only about a quarter did in the 1930s.

Are all those Americans who resolved, in lieu of weight loss or fiscal sobriety, to be “better people” last year the avant-garde of a return to the socially and spiritually unifying New Year’s resolutions of the past? Time will tell. But don’t get your hopes up in either case: a 2007 University of Bristol study revealed that 88 percent of New Year’s resolvers failed to achieve their goal.

It’s not all gloomy, though. Research has shown that announcing your resolutions to supportive friends and family and keeping them specific sharply increase your odds of success. So, if you’re making a resolution this year, do as our ancestors did: add a little pomp, keep it social (and religious if that’s your bent), and state your goal plainly. Michael Hyatt’s just-released book, Your Best Year Ever, can help with that. Ancient Babylonians would approve.

10 Rules to Read More Books This Year

How to Make Reading Central to Your Personal Growth in the Coming Year

One New Year’s resolution I frequently hear from people is that they want to read more books. Makes sense if you consider reading a key component of personal growth and development.

Ray Edwards recently wrote about his reading goals here at MH&Co. He planned to read fifty-two books in a year. Instead, he read seventy-six! Edwards said he invests in reading because it helps him learn new ideas, upgrade his thinking, and improve his leadership. But seventy-six books! Who’s got time for that?

My fifty-book challenge

I read a lot and have done so since my teens. But even fifty-two books in a year would have seemed like a stretch to me—until a decade ago.

I was an editor at a publishing house and on the phone with one of my authors. I mentioned being on a fiction bender and offhandedly gave the number of novels I’d read during my spree. He was encouraging but unimpressed. Fifty books a year was the norm for him. At my then-current pace, the best I could hope for was a sum in the low thirties.

The next year I started keeping record of every book I finished. As a writer and editor, I’m in and out of far more books than I actually read cover to cover. I wanted to know how many I had actually completed. After twelve months, I finished thirty-five.

How on earth did my author friend hit fifty? It seemed impossible given my job, family, and social obligations, not to mention other claims on my time. But I kept at it, and the number rose the next year. And the next. And the next. Nowadays I typically read fifty books a year on top of the countless books I browse, scan, or quit.

And here’s how I do it. Whatever your reading goal, these ten rules can probably help you finish more books this year than last.

10 rules to read more books

1. Keep track. If you’re looking to read more, one of the easiest methods is simply logging what you read. When my list of completed titles is short, I want to read more. When it’s long, I get a surge of pride and excitement and want make it longer. I also get a charge when I survey what I’ve learned or felt in my reading over the past several months. More, please.

2. Switch formats. I love physical books. I also love audiobooks and tolerate ebooks. But I’m happy to switch between all three formats to finish a book, especially paper and audio. I’ll listen while I drive and then find my place in my copy on my nightstand later that evening. For books I regularly reread, such as Montaigne’s Essays, I keep all three formats handy so I can read whenever, wherever the mood strikes.

3. Cut back on TV. There’s so much great TV being produced these days. But there are only 8,765.82 hours in a year. Deduct for sleep, work, family, dining, and driving and then ask: Do I really want to binge watch that new series? No judgment if the answer’s yes, but opportunity costs are real. I can’t read and view at the same time.

4. Kill your social media apps. I have a Kindle but never use it. My iPhone 7 Plus is my preferred digital reader. It’s also my audiobook player. I regularly use the Kindle, Audible, and Scribd apps. To safeguard my screen time for reading when opportunities arise, I have deleted social media apps from my phone. Social media (and news) apps present the same basic problem as TV. I backslide from time to time, but quickly remember the opportunity cost. Facebook is the enemy of real books.

5. Take books everywhere. I always have a book with me: sometimes one or more physical books and several dozen audio and digital a few taps away on my phone. If I’m waiting, I’m reading. If I’m walking, I’m reading. Every week there are minutes that come to hours of unclaimed time at the margins. I can use it to stare at my shoes—or read three more pages in my book. Shoes are nice, but books are better.

6. Follow your whims. In his book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, Alan Jacobs expresses his “commitment to one dominant, overarching, nearly definitive principle for reading: Read at Whim.” This has served me well. I let my tastes, curiosity, and passions steer my eyes. That way I read more of what I love—with the bonus that I also love more of what I read.

7. Vary your genres. Part of following my whims is reading across several genres. Even during times I’ve narrowed my focus, I try to let random titles land on my list. If I’m digesting a lot of history, a zany novel might be called for. If I’ve spent months cornering one subject, I try to find something utterly different to break it up.

8. Read several books at once. I don’t mean simultaneously. That’s impossible (though I do hope they figure it out someday). I mean I have several books going at any given time: two or three histories at various stages, a bio, a business book or two, something spiritual, and usually a novel. With that much variety, I’m always in the mood to read at least one in the stack.

9. Seek suggestions. Where social media does come in handy for me is reading suggestions. I’m great at finding new books, but I love hearing what my friends, industry colleagues, mentors, and others are reading. There are hundreds of thousands of books published every year. There’s simply no way for an individual to know all the best books on any particular topic. One of the things I love most about our LeaderBox program is the surprise subscribers express when they see the new books each month—sometimes titles they’d never discover on their own.

10. Quit at any time. Over the years I’ve heard several people say they stopped reading for a while because they just couldn’t finish a particular book. It was boring, bad, whatever. That’s like saying you stopped eating because you don’t like meatloaf. Drop it in the trash and try tacos. Or salmon. Or curry. Or something! There are a million books available, at least some of which are better than whatever you can’t finish.

This one is more than a rule. It’s a motto, a way of life: I’ll quit any book at any time. Life’s too short to soldier through an uninteresting book. And there’s no way I’ll let one stop me from reading a dozen more-likable volumes.

“

I’ll quit any book at any time. Life’s too short to soldier through an uninteresting book.

—JOEL J. MILLER

You can read more than you think

So how many books are you planning on reading this year? My guess is you’re capable of more than you think. Consider that the average book is about 65,000 words long, and a typical reader can cover about 300 words a minute.

At that rate, you could finish in just over three and half hours. If you read thirty minutes each day, that’s one book every week, give or take. Fifty or so a year. Reclaim a few extra minutes here and there throughout the day, and it’s easy to see how Edwards found his way to completing seventy-six books in a year. Whatever the right number for you, there’s more than enough time this year to reach it.