Michael Hyatt's Blog, page 47

April 17, 2018

Beginner’s Guide to Journaling

5 Simple Steps to Greater Self-Awareness

We all know that being a great leader means practicing self-awareness. But that’s incredibly hard to do in a consistent way. In this episode, we show you how the simple practice of writing for a few minutes a day can help you avoid making mistakes based on pride or ignorance and make solid decisions by being aware of your own motivations.

The Magic of an Outside Perspective

Five Steps to Learning from Mentors in the Digital Age

Personal growth comes from self-awareness, and the practice of journaling is a phenomenal way to start that process with regular reflection—as long as your reflection is accurate.

If you’ve ever been to a playground or circus with fun mirrors, you know the slightest bend to a mirror creates a distorted image that reflects your image different than you actually are. Self-reflection works the same way.

At the circus, it’s easy to recognize distorted images. You’re reflected as stretched out or squeezed, ridiculously tall or comically short and stout.

In daily life, distortions are often much smaller. How do you know when your self-reflection is distorted by subtle bends that are throwing you off?

Reading your label from inside the bottle

Donald Miller explains this self-reflection distortion with a comical example, where he had one client complain that they felt like they were trying to read the label from inside the bottle. With that image in mind, it’s no surprise that it’s difficult to “read your own label” with accuracy. Thinking about yourself as yourself inherently limits your perspective.

The only way to overcome this challenge is to expose yourself to mentors who can provide an outside perspective. Luckily, in today’s world, your next mentor is only a click or two away.

Mentorship hasn’t died off, but it has drastically changed with the digital age. It’s now fairly uncommon to have formal 1-on-1 mentorship relationships (though if you have a trusted mentor like that, be grateful for the advantage it brings).

“

Mentorship hasn’t died off, but it has drastically changed with the digital age.

—JOHN MEESE

Today’s mentors can be found on blogs and magazines (like this one), as well as podcasts and YouTube channels, or at in-person live events. The changing mentorship landscape requires a new learning approach. You can adopt this approach with five simple steps:

Step 1: Identify areas of desired growth

In today’s era of increased specialization, you can find a digital mentor on nearly any topic you can think of—the first step is to identify where you need the most help.

If you’re journaling daily, you may find repeated themes where you’re falling short in certain areas of your life. Similarly, you may have specific goals you fall short on each year, that you can’t seem to accomplish on your own.

Having a mentor in every life domain sounds compelling, but your time and attention is limited. You’re better off narrowing your focus to the one or two areas of life where you most need an outside perspective right now.

Step 2: Select specialized mentors

Once you’ve identified the areas in which you need an outside perspective, the next step is to select a trusted mentor for each focus area.

You don’t want multiple mentors in each area, because you’re likely to get lost in the confusion of who to follow when advice from multiple mentors doesn’t match up.

For personal finance, you might decide to follow Dave Ramsey. For leadership or productivity, you’d likely follow Michael Hyatt (since you’re here). I’m admittedly biased, but for online business or building an audience, Platform University would be your best bet.

“

Once you’ve identified the areas in which you need an outside perspective, the next step is to select a trusted mentor for each focus area.

—JOHN MEESE

Step 3: Commit to consuming content

Selecting your digital mentors isn’t enough. You also need to commit to consuming your digital mentor’s content, so their perspective can influence your own.

That often starts with blog posts or podcasts, but could also mean live video training or upgrading to a paid experience to commit to deeper learning and transformation over time.

Step 4: Check your progress with digital tools

In a 1-on-1 mentor relationship, regular check-ins are a great way to get an outside perspective on where you’re at, how you’re growing, and what you need to watch out for next.

In digital mentorship, direct coaching is limited. To account for that, you need to intentionally seek out tools like The Platform Assessment that identify what’s holding you back from success.

These tools often end with recommendations for next steps, which you may not have thought up on your own.

Step 5: Reassess your needs every year

Seasons change, and the mentors you follow today may not be the same mentors you need to follow a full year from now.

What this does not mean is that you should bounce from mentor to mentor, moving on whenever you get a piece of advice you don’t like. It’s important you commit to following your mentors even when their advice becomes difficult (unless you have a moral or ethical objection).

As you put your mentor’s advice into practice, you should see continued growth. Once a year is a good cadence for reassessing your current needs, and refocusing on areas of your life that need attention as your needs change.

If your goals include building an online audience, I hope you’ll consider Platform University’s Webinar Training in your digital mentorship focus. Michael Hyatt and I will be teaching 3 Secrets to Exponential Audience Growth: How to Build an Engaged Online Following in Just 30 Minutes a Day. As I write this, there are several opportunities remaining to join us live!

Hit the Ground Writing

How to Be More Consistent in Your Journaling

Life is a great teacher. But you have to pay attention and take notes if you want to be a great student. That’s why I made journaling a regular part of my morning ritual several years ago.

Journaling helps me clarify my thinking, process my feelings, and make better decisions. It’s also cheaper than therapy! But like most people, I haven’t always been consistent. In the past, I really wanted to journal. I was convinced of the benefits. But I found myself blowing it off with increasing frequency. Sound familiar?

Thankfully, a few years ago I stumbled on something that solved the problem for me. Not one hundred percent of the time, but most of the time. At first, I didn’t think it was a big deal. It seemed too simple. But I shared it with my wife, Gail, who was struggling with consistency herself. After successfully using it for a few weeks, she said, “Honey, you have got to blog about this.”

So here’s what I shared with her: Use a journaling template.

Not that earth-shattering, right? I didn’t think so. I template almost everything I do so I don’t have to constantly reinvent my workflows. I want to document the process and then improve it over time.

“

Using a template gives me a track to run on. I get started and then the process takes over.

—MICHAEL HYATT

That’s exactly what I’ve done with my journaling template. I have gone through several iterations, and I am sure I will go through more. It basically consists of eight questions broken down into three parts.

This template assumes I’m journaling in the morning. As I mentioned at the start, it’s part of my morning ritual. A good night’s sleep puts the previous day’s events into perspective for me. I’m not at my most resourceful at night.

Yesterday

What happened yesterday? I don’t chronicle everything, of course. I write the highs, lows, and anything I want to remember later.

What were my biggest wins from yesterday? This gives me a sense of momentum to start the new day.

What lessons did I learn? I try to distill my experience down into a couple of lessons I want to remember. It’s not what happens to us but what we learn from it that matters most.

Now

What am I thankful for right now? This is one practical way I can cultivate a sense of abundance and gratitude.

How am I feeling right now? Feelings aren’t the be-all-end-all, but they’re a clue. In the past, I just ignored or suppressed them. This gives me an opportunity to check in on myself.

Today

What did I read or hear? Here I list important books, articles, Bible passages, or podcasts I consumed since I last journaled.

What stood out? I don’t want to lose what I learn in my reading and listening, so I record key insights.

What can I do next to move forward on my goals? I think through my goals and my schedule and identify a few key actions I could take to make progress. This helps me prioritize.

Note: The descriptive text above is simply for your benefit. It’s not actually part of the template.

I had been using Day One to journal for the last few years. However, I have shifted to using a prototype of our new Full Focus Journal .

.

One size doesn’t fit all, so feel free to adjust the template or questions however they work best for you.

When I used a digital option, to make it easy, I kept the template in TextExpander. It’s one of my key productivity tools. I just typed ;je (as in “journal entry”) and TextExpander replaced that text with my template. Here’s a quick screencast to show you how this works.

If you can’t see this video in your RSS reader or email, then click here.

If you want to copy and paste my template into your text expander or some other tool, you can download it here. And if you want a quick take on how to use multimarkdown, try my beginner’s guide.

For me, journaling is a means to an end. It helps me think more deeply about my life, where it is going, and what it means.

“

Journaling is a means to an end. It helps me think more deeply about my life, where it is going, and what it means.

—MICHAEL HYATT

The advantage of using a template is that it gives me a track to run on. This is especially helpful on those mornings when my brain is a little foggy or I don’t particularly feel like writing.

All I have to do is get started and then the process pretty much takes over. I spend fifteen minutes. No more, no less.

Journaling for Self-Awareness

3 Tips for Seeing Yourself More Clearly

Charley Kempthorne has been keeping a journal for more than 50 years. Every morning before the sun is in the sky, the professor-turned-painter carefully types out at least 1,000 words reflecting on his past, his beliefs, his family, even his shortcomings. The prolific fruits of his labor reside in an impressive storage facility in Manhattan, Kansas, where his estimated 10 million words are printed, bound, and filed.

This project, Kempthorne says, is an end in itself: “It helps me understand my life . . . or maybe,” he hedges, “it just makes me feel better and get [the day] started in a better mood.” But Kempthorne might be disappointed to learn that his enduring exercise may not have actually improved his self-awareness.

The journaling trap

At this point, you’re probably convinced I’ve gone completely off the deep end. Everyone knows, you might be thinking, that journaling is one of the most effective ways to get in touch with our inner self!

However, a growing body of research suggest that introspection via journaling has some surprising traps that can suck the insight right out of the experience. My own research, for example, has shown that people who keep journals generally have no more internal (or external) self-awareness than those who don’t.

How can we make sense of these peculiar and seemingly contradictory findings? The solution lies not in questioning whether journaling is the right thing to do but instead discovering how to do journaling right.

“

The solution lies not in questioning whether journaling is the right thing to do but instead discovering how to do journaling right.

—TASHA EURICH

Psychologist James Pennebaker’s decades-long research program on something he calls expressive writing provides powerful direction in finding the answer. It involves writing, for 20 to 30 minutes at a time, on our “deepest thoughts and feelings about issues that have made a big impact on [our] lives.” Pennebaker has found that it helps virtually everyone who’s experienced a significant challenge. Even though some people find writing about their struggles to be distressing in the short term, nearly all see longer-term improvements in their mood and well-being.

Pennebaker and his colleagues have shown that people who engage in expressive writing have better memories, higher grade point averages, less absenteeism from work, and quicker re-employment after job loss.

Intuitively, one might think that the more we study positive events in our journal entries, the more psychological benefits we’ll reap from the experience. But this is a myth. In one study, participants wrote about one of their happiest times for eight minutes a day over the course of three days. Some were told to extensively analyze the event and others were instructed simply to relive it.

The analyzers showed less personal growth, self-acceptance, and well-being than those who relived it. Why is this the case? By examining positive moments too closely, we suck the joy right out of them. Therefore, the first take-home in seeking insight from journaling is to explore the negative and not overthink the positive.

“

Even though some people find writing about their struggles to be distressing in the short term, nearly all see longer-term improvements in their mood and well-being.

Another trap journalers can fall prey to is using the activity solely as an outlet for discharging emotions. Interestingly, the myriad benefits of expressive writing only emerge when we write about both the factual and the emotional aspects of the events we’re describing—neither on its own is effective in producing insight.

Logically, this makes sense: if we don’t explore our emotions, we’re not fully processing the experience, and if we don’t explore the facts, we risk getting sucked into an unproductive spiral. True insight only happens when we process both our thoughts and our feelings.

Moderation, even in reflection

The final thing to keep in mind about journaling should be welcome news to everyone but Mr. Kempthorne. To ensure maximum benefits, it’s probably best that you don’t write every day. Pennebaker says, “that people should not write about a horrible event for more than a couple of weeks. You risk getting into a sort of navel-gazing or cycle of self-pity. But standing back every now and then and evaluating where you are in life is really important.”

Of course, if you’re a prolific journaler, the right approach may require some restraint. But with a little self-discipline, you can easily train yourself to write less and learn more.

The capacity for self-examination is uniquely human. Though chimpanzees, dolphins, elephants, and even pigeons can recognize their images in a mirror, human beings are the only species with the capacity for introspection—that is, the ability to consciously examine our thoughts, feelings, motives, and behaviors. But many people are doing it wrong.

The capacity for self-examination is uniquely human. Though chimpanzees, dolphins, elephants, and even pigeons can recognize their images in a mirror, human beings are the only species with the capacity for introspection—that is, the ability to consciously examine our thoughts, feelings, motives, and behaviors. But many people are doing it wrong.

By avoiding these three pitfalls on the journey to self-discovery, you can realize the greatest benefit of journaling—to know yourself.

Reprinted (or Adapted) from Insight: Why We’re Not as Self-Aware as We Think, and How Seeing Ourselves Clearly Helps Us Succeed at Work and in Life ©2017 by Tasha Eurich. Published by Crown Business, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

April 10, 2018

Cornering the Paper Tiger

Why Leaders Should Junk the Technological Fallacy

Studying the history of paper, as I did while writing the book Paper: Paging Through History, exposes a number of misconceptions. The most important of which is this technological fallacy: the idea that technology changes society. It is exactly the reverse. Society develops technology to address the changes that are taking place within it.

To use a simple example, in China in 250 BCE, Meng Tian invented a paintbrush made from camel hair. His invention did not suddenly inspire the Chinese people to start writing and painting or to develop calligraphy. Rather, Chinese society had already established a system of writing but had a growing urge for more written documents and more elaborate calligraphy.

Their previous tool – a stick dipped in ink – could not meet the rising demand. Meng Tian found a device that made both writing and calligraphy faster and of a far higher quality.

The rising need for paper

Chroniclers of the role of paper in history are given to extravagant pronouncements: Architecture would not have been possible without paper. Without paper, there would have been no Renaissance. If there had been no paper, the Industrial Revolution would not have been possible. None of these statements is true. These developments came about because society had come to a point where they were needed. This is true of all technology, but in the case of paper, it is particularly clear.

As far as scholars can tell, the Chinese were the only people to invent papermaking, though the Mesoamericans may also have done so; because of the destruction of their culture by the Spanish, we cannot be sure. And yet, paper came into use at very different times in very different cultures as societies evolved and developed a need for it and circumstances required a cheap and easy writing material.

Five centuries after paper was being used widely by the Chinese bureaucracy, Buddhist monks in Korea developed a need for paper also. They adopted the Chinese craft and took it to Japan to spread their religion. A few centuries later, the Arabs, having become adept at mathematics, astronomy, accounting, and architecture, saw a need for paper and started making and using it throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain.

The Europeans initially had no use for paper until more than a thousand years after the Chinese invented it. It was not that they had only just discovered the existence of paper, however. The Arabs had been trying to sell it to them for years. But it was not until they began learning the Arab ways of mathematics and science, and started expanding literacy, that parchment made from animal hides-their previous writing material-became too slow and expensive to make in the face of their fast-growing needs.

“

Technology doesn’t change society. It is exactly the reverse. Society develops technology to address the changes that are taking place within it.

—MARK KURLANSKY

If not paper, what?

The growth of intellectual pursuits and government bureaucracy, along with the spread of ideas and the expansion of commerce, is what led to papermaking. But its international growth was a remarkably slow process. The use of printing presses, steam engines, automobiles, and computers spread internationally over far shorter periods of time than did paper.

Paper seems an unlikely invention. Breaking wood or fabric down into its cellulose fibers, diluting them with water, and passing the resulting liquid over a screen so that it randomly weaves and forms a sheet is not an idea that would logically come to mind, especially in an age when no one knew what cellulose was. It is not an apparent next step like printing, which various societies would arrive at independently.

Suppose no one had thought of paper. What then? Other materials would have been found. Improved writing material had to be found because the needs of society demanded it.

Moleskine Mania

Why We Shouldn't Paper Over This Success Story

If you ever attend Milan’s Design Week—a sweeping furniture fair, art festival, and Prosecco-soaked party that takes over Italy’s financial capital each April—you will need several essentials to fit in with the global trendsetters in attendance.

First, your glasses. This is a design crowd, so the options are polarized into two camps: ultraminimal frameless spheres that hover over your face, and inch-thick acetate beasts. Next, your clothes. Leave ankle-snapping heels and impossible dresses to the fools at Fashion Week; the name of the game here is the ideal mix of form with function, such as a limited-edition pair of Converse clad in sharkskin. Also scarves. You can never wear too big a scarf at Design Week, even if a sudden heat wave descends on the city.

Finally, there’s your kit. If you carry a bag, it needs to be small, streamlined, and slung over the shoulder. In one hand, firmly grasp the latest iPhone, which you’ll use to take photos of new chairs and kitchen tile installations, stay in touch with colleagues, and navigate your way between parties and events all over Milan.

In hand number two

In the other hand, you will carry a black Moleskine notebook. Perhaps you will bring the same, lovingly worn Moleskine back to Milan year after year, or maybe you will unwrap a fresh one at the start of every Design Week. You will jot quick notes and sketches in it as you tour showrooms and exhibits, and at the end of each long day, you will open it on a café table, order a cold Peroni and a plate of mortadella, put pen to paper, and digest all the exhibits, products, and far-reaching designs you’ve seen since the morning. You might start by writing lists of words, maybe descriptive adjectives, or a few lines of insights that tease out this notion you have forming about the organic desire for analog experiences in a hyper-digitized age.

After a page or two, you’ll stop, take a sip of your beer, and look around. You’ll draw inspiration from the pale gold of the beer, the beautifully irregular spots of the mortadella, the bleached ceramic plate it sits on . . . and suddenly you’ll be designing your own textile line, filling pages almost as fast as you can turn them, with sketches and words and feverishly added details.

Milan Design Week 2017

Yes, I am being romantic, and perhaps mortadella isn’t a traditional muse. But this is exactly what I saw at the end of each day during my visit to Milan in the middle of Design Week. Moleskines . . . hundreds of them, thick with the ideas being written and sketched in them by the most talented and driven design minds in the world. Old designers, young designers, European designers, and Asian and Latin-American designers—the Moleskine notebook is their common tool. You certainly do not need to visit Milan to witness this. Just step into any coffee shop, pretty much anywhere in the world, and you will find Moleskine notebooks resting on tables next to lattes and laptops. With their rounded corners, elastic closure, and ivory paper, they are instantly recognizable. Which is why I see them everywhere: in the hands of teachers, on my doctor’s desk, in the bags of computer software programmers.

Nearly everyone I interviewed for my book, The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, pulled out a Moleskine notebook at some point, or had one sitting nearby. For a thoroughly analog object, the Moleskine is one of the iconic tools of our digitally-focused century.

Nearly everyone I interviewed for my book, The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, pulled out a Moleskine notebook at some point, or had one sitting nearby. For a thoroughly analog object, the Moleskine is one of the iconic tools of our digitally-focused century.

I am fascinated by Moleskine for several reasons. Paper was the first analog technology to be seriously challenged by digital. Even before the rise of the personal computer, the term paperless office had emerged as an obsession of the business world by the late 1970s. The promise of a computer reducing the cost, labor, and space associated with printing, storing, and organizing so much physical information was powerful. Office workers were called “paper pushers” for a reason, and less time pushing paper meant more time, and money, devoted to other work. Although the fully paperless office has yet to come to fruition, certain paper artifacts are now largely digital. E-mail, texts, and PDFs have taken the place of memos, telegrams, and faxes. When I entered university in 1998, I was one of the few students to take class notes on a miniature laptop. Today, screens overlook college lecture halls. Paper hasn’t disappeared, but it is no longer dominant.

Paper is also the oldest analog technology to be seriously challenged by digital. Vinyl records had been around less than forty years when the CD came out, but paper has existed, in one form or another, for thousands of years. It is the backbone of the economic, cultural, scientific, and spiritual core we call civilization. Even the bound notebook, the core technology behind Moleskine’s main product, predates European settlement of the Americas. Our relationship to paper is older, deeper, and more varied than any other analog technology out there. Understanding where paper’s advantages lie, where it has struggled to compete with digital technology, and where it has crafted a new sense of identity is key to understanding how the Revenge of Analog is playing itself out.

Where paper is growing

The revenge of paper shows that analog technology can excel at specific tasks and uses on a very practical level, especially when compared to digital technology. While paper use may have shrunk in certain areas since the introduction of digital communications, in other uses and purposes, paper’s emotional, functional, and economic value has increased. Paper may be used less, but where it is growing, paper is worth more.

“

The revenge of paper shows that analog technology can excel at specific tasks on a very practical level, especially when compared to digital technology.

—DAVID SAX

From the get-go, Moleskine knew that its notebooks wouldn’t exclusively contain the brilliant creations of the next Picasso. There would be a lot of melodramatic teenaged diaries, half-baked doodles and class notes, and grocery lists. But because they were written in a Moleskine, they would still feel more creative than if they were scribbled on another piece of paper.

“Creativity is a word that’s now completely sold,” Maria Sebregondi, the founder of Moleskine, said, “but the concept behind it is strong and real. People want to be creative and feel creative, even if they are not. Creatives have the ability to create an emotional trigger, and the analog world is the one able to create this emotional attraction and experience.”

This formed an almost tribal identity around the Moleskine notebook and those who used it. The notebook became a symbol of aspirational creativity, a product that not only worked well as a functional tool, but that told a story about you, even if you never wrote on a single page. Like a Patagonia jacket or a Toyota Prius, it projected someone’s values, interests, and dreams, even if those were divorced from the reality of their lives.

This is why Moleskine never needed to advertise, and never does to this day. Each notebook spotted at a coffee shop table, or in the hands of a journalist, was worth more than any billboard or magazine page. “This is a company that went from being a category maker to a category icon,” said Antonio Marazza, general manager at the Milan office of the global branding agency Landor Associates. “The emotional and aspirational capital Moleskine can deliver goes beyond stationery.”

This article is an adapted excerpt from The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter (Used by permission). Published in November 2016 by PublicAffairs, an imprint of the Hachette Book Group.

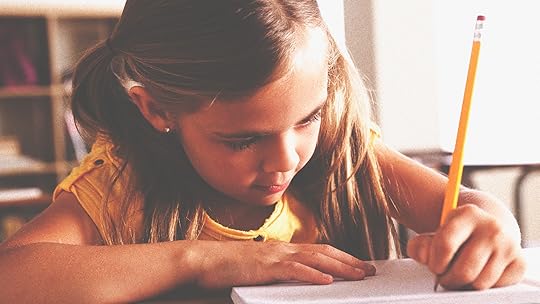

The Science of Putting Pen to Paper

Studies Show: It Forces You to Focus

One of my earliest memories involves a handwriting struggle. My class had been tasked with writing stories. I love stories. My masterpiece, about accidentally catching a great white shark and putting him into my bedroom aquarium, was the longest in the class.

It was pages and pages long. It had chapters. I was in child-heaven until my teacher told us that we would be copying our stories into nice, hardcover books using our most perfect handwriting.

I spent more recesses than I can count sitting at my desk painstakingly writing into the book. My teacher eventually took pity on me and finished the final “chapters” herself. Her handwriting was shockingly better than mine.

I still have terrible handwriting, but I write constantly. Pulling out a laptop on the train to jot down random ideas seems unnecessary and also less romantic. Taking handwritten notes at lectures has always come more naturally to me than typing. I like arrows, explanatory margin notes, and multi-colored pens. My go-to study habit involves rewriting study guides ad nauseum, but only the points I haven’t mastered yet, silently repeating them to myself as I dot my i’s and cross my t’s.

Today, I am incredibly thankful for every teacher that made me sit at my desk and learn to write by hand. As researchers delve into the science of putting ideas to paper the old-fashioned way, benefits of writing with pen and paper are difficult to ignore. Writing is undeniably linked to learning.

“

The benefits of pen and paper are difficult to ignore. Writing is undeniably linked to learning.

—ERIN WILDERMUTH

Learning to write

The benefits of writing begin with learning to write. Mastery takes years of tracing Rs and practicing Qs, with young children graduating from print to cursive over time. Though Common Core learning demoted handwriting, research has prompted a comeback. Today, many states require that students be taught cursive, and for good reason.

In one study, children tasked with writing an essay delivered longer, higher-quality essays when writing by hand. (This may, in part, explain my chapter book.) In another study, children were asked to write, trace or type various letters. They were then shown the letters while researchers performed fMRI scans. When shown letters they had written, parts of the brain associated with reading lit up with activity. This response was dampened when traced letters were shown. Letters that had been typed elicited the smallest response.

These results are also documented in real-time learning. When a group of preschool students was divided into two groups—one training in handwriting and the other on a keyboard for sixteen session—the handwriting group outperformed their peers not only in writing, but also in reading assessments. The typing group did not excel beyond their peers in any field tested.

Writing is much more than just putting pen to paper. It is a dynamic part of our language, inseparable from literacy. Forming letters manually helps children to connect those letters with our alphabet and associate shape with sound. With language being a common vessel of knowledge dissemination, it is no wonder writing plays a crucial role in learning.

Writing to learn

The benefits of writing continue long after we’ve mastered the basics of penmanship. A simple study conducted in 2015 had women aged 19-54 either handwrite, type on a keyboard, or use an iPad to write words. Those that had written by hand were significantly better at recalling the words they had written. The only difference in the study was the mode of writing, indicating that physically shaping words helps us to remember them.

Haptics studies, which look at touch as a mode of communication, suggest that visuomotor skills are the reason for this phenomenon. Touch is an important sense, and when we engage across multiple sensations we are better able to tie things together, recall them later and, in short, learn. The feel of a pen being delicately manipulated to produce the small scratches of ink that make up words on paper is far more tactile than fingertips pressed against slabs of plastic.

Beyond haptics, social scientists have pointed to practical benefits of writing by hand.

In a 2014 study, researchers confirmed that students learn better when they take notes on paper. They reason that the slower speed of handwriting forces students to consolidate and reword lectures, helping them to process and retain new information. When students who used laptops were asked to consolidate information in their notetaking, they still used more words and did not reap the benefits of the handwriting group.

Towards embracing both writing and typing

It is easy to get comfortable with one form of writing, and most people will admit to having a bias towards either writing by hand or typing. Both have benefits. When words and sentences need to flow in real time, typing at nearly the speed of thought is an amazing convenience.

Other times, we want or need extra time to feel the weight of our words or incorporate an idea into long-term memory. Taking the time to identify what kind of writing you’re doing will help you choose the most effective tool for any circumstance.

Your Own Personal Time Machine

5 Simple Ways to Recover the Lost Art of Note Taking

If you spend much time in meetings or presentations, note taking is a survival skill. So I’m surprised at how few people bother to do it. Those who do sometimes express frustration at how ineffective it can be.

I don’t recall anyone ever teaching me how to take notes. I didn’t learn it in school—not even in college. Nor did I learn it from others on the job. It was something I had to pick up on my own.

That’s probably true for a lot of people, and I bet it’s why so few people bother to take notes. No one has ever told us why it’s important or how to do it. That ends here. I’m going to share not only why you should take notes but also offer four suggestions on how to do it better.

Reasons for note taking

To begin with, note taking enables you to stay engaged. The real benefit is not what happens after the meeting but during the meeting itself. Taking notes not only keeps us focused, it also triggers critical, constructive thinking.

If I don’t take notes in meetings or presentations, my mind wanders. But when I do, I stay more alert and involved. As a result, my contribution is more likely to add value. For this reason, I take notes even if someone is officially taking minutes.

Note taking also captures in-the-moment insights, questions, and commitments. Not everything can be resolved immediately. Some ideas take incubation. Questions require further research. Commitments require followup that cannot be done until after the meeting. Without a way to capture these, they’ll just get lost.

“

If you take notes, your people will likely take notes.

—MICHAEL HYATT

Your notes are like a time machine that let you go back days, weeks, even years. I can’t tell you how many times my notes have saved my bacon—not only when trying to resolve a dispute, but in holding people accountable or retrieving a key insight I subsequently forgot.

Finally, note taking communicates the right things to the other attendees. This is probably my favorite reason of all. When someone takes notes, it communicates to everyone else that they’re actively listening and that what others are saying is important.

If you’re in leadership, it also subtly establishes accountability. Your people think, If the boss is writing it down, he probably intends to follow-up. I’d better pay attention. As a leader, your example speaks volumes. If you take notes, your people will likely take notes. If you don’t, it is likely they won’t.

But how can you more effectively take notes?

1. Choose the right tool

If you have something that’s working for you, great. It could be a state-of-the-art app or yellow legal pad. Whatever’s working for you, stick with it. I usually recommend a journal-formatted notebook. I currently use the daily notes section of my Full Focus Planner and never go anywhere without it.

and never go anywhere without it.

2. Give your notes structure

Especially if the meeting or the presenter is unstructured. I give each new meeting or subject its own heading, along with the current date. Imposing order and hierarchy with headers, numbered sections, and nested bullets is a big help. This focuses your thinking and simplifies review and retrieval.

3. Record whatever’s important or interesting

I recommend recording any or all of the following things: the presenter’s outline, questions being asked or addressed, key insights you have independent of what’s being said, along with any useful illustrations, jokes, anecdotes, diagrams, or quotes.

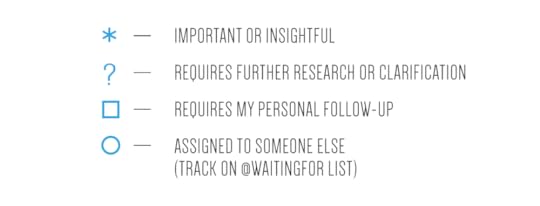

4. Use symbols so you can quickly scan your notes later

I indent my notes from the left edge of the paper about half an inch. This allows me to put my symbols in the left margin. I use four:

If an item is particularly important or insightful, I put a star next to it.

If an item requires further research or resolution, I put a question mark next to it.

If an item requires follow-up, I put an open square next to it. When the item is completed, I check it off.

If I have assigned a follow-up item to someone, I put an open circle next to it. In the notes, I indicate who is responsible—or just put their initials in the circle. When the item is completed, I check it off.

(By the way, this system is built into my Full Focus Planner .)

.)

5. Schedule time to review your notes

This is key. I scan my notes immediately after the meeting if possible. If that is not possible, then I do it at the end of my workday. If I miss several days, I do it during my weekly review.

Regardless, I take action on those items that I can do in less than a few minutes. Those that will take longer I drop in my task manager and intentionally procrastinate till a later date.

No one can count on total recall. Great notes are the closest thing to a time machine we’ll ever get.

“

Note taking is a survival skill.

—MICHAEL HYATT

The Most Overlooked Productivity Solution

Why Every Leader Should Re-Adopt This Tried-and-True Technology

We all want to be more productive, but we’re drowning in a sea of productivity apps and hacks. We’ll show you why every leader should re-adopt a well-known—but often overlooked—productivity solution: paper! By using paper in some situations, you can avoid wasting time and money on solutions that don’t work and focus on your most important goals.

April 3, 2018

Look for the Good Apples

Leverage Your Attitude, Save the Whole Barrel

When the conversation turned to his status as the first American to hold the much-coveted WBC World Heavyweight Championship belt in eight years, no one would’ve batted an eye if Deontay Wilder attributed the achievement to his considerable skill and punching power.

Instead, the former Olympic bronze medalist boxer explained, “When one guy is doing good, it makes all the others want to achieve greatness. It’s contagious to do great. But once that one bad apple falls, everybody else will fall, and that’s how it is.”

Apples in a barrel

Though your own “ring” may look suspiciously like an office and be devoid of uppercuts and left hooks, this “greatness contagion” does not observe such boundaries. No matter the theoretical architecture of your barrel, the quality of the apples you share it with matters.

An actual bad apple in an actual barrel, according to Mental Floss, emits the “gaseous hormone…ethylene”—a ripening agent, which, concentrated, can trigger the same effect in other fruit. “Given the right conditions and enough time,” the author explains, “one apple can push all the fruit around it to ripen and eventually rot.”

The same concept applies to people, with one huge exception. One “single, toxic team member” has been shown to serve as “catalyst for group-level dysfunction.” That was one finding of a 2006 paper in the journal Research in Organizational Behavior aptly titled, “How, When, And Why Bad Apples Spoil the Barrel: Negative Group Members And Dysfunctional Groups.”

And here’s the huge exception that scientists found: With people, it only takes one good apple to save the barrel. That’s good news, and it gets better. With the proper interpersonal skillset and knowledge base, you could, in fact, be that apple.

Learn to recognize your “Nick”

Dan Coyle opens his fascinating deep dive into The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups with the story of how University of South Wales professor Will Felps managed to force the “bad apple” effect out into the open for closer study.

Dan Coyle opens his fascinating deep dive into The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups with the story of how University of South Wales professor Will Felps managed to force the “bad apple” effect out into the open for closer study.

It begins with mischievous-yet-brilliant experiment concocted by Felps in which he brought together forty four-person groups “tasked with constructing a marketing plan for a start-up”—then injected “Nick,” an actor embodying three “bad apple” stereotypes: The Jerk, the Slacker, and the Downer.

“Nick is really good at being bad,” Coyle writes. “In almost every group, his behavior reduces the quality of the group’s performance by 30 to 40 percent. The drop-off is consistent whether he plays the Jerk, the Slacker, or the Downer.”

Previous research suggests this is not a fluke. As Felps himself noted in his 2006 Bad Apples paper, “simply observing another person’s expressions of effect can generate those feelings in others” and “subjects working together on a task partially adopted the confederates mood.”

Further, “whereas a positive emotion (i.e. compassion) wears off relatively quickly, researchers find that when they give someone a negative feeling (i.e. anger) to concentrate in, the physiological effects last over 5 hours.” In geek terms, the dark side of this force is strong.

“

It only takes one good apple to save the barrel. With the proper skillset and knowledge, you could be that apple.

—SHAWN MACOMBER

Perhaps worst of all, the bad outcomes these phenomena may engender can gain destructive momentum. “After a team failure occurs,” Felps et al write, “the negative member behaviors are more salient, and thus more influential.”

Before we begin our campaign to have the Academy create a Best Actor in a Social Science Experiment category, however, it’s important to note our antihero was not able to get all his targets to go bad.

The downward spiral: a cautionary tale

In designing the experiment, Felps recognized that options for dealing with a bad apple were limited. In fact, the professor boiled it down to three, none of them very appealing.

The first, “motivational intervention,” is essentially an attempt to reform the negative employee by, say, “withholding of praise, respect, or resources until behavior changes, subtle and not so subtle confrontations, formal administrations of punishments, or demands of apology and compensation.” Second is “rejection,” or kicking the troublesome internal agitator to the curb.

“If either the motivation intervention or rejection is successful,” Felps writes, “the negative member never becomes a bad apple or spoils the barrel.”

For whatever reason, if the first and second options are not possible, frustrated team members may descend into the third option, “defensive self-protection,” manifestations of which can include “lashing out, revenge, unrealistic appraisals, distraction, various attempts at mood maintenance, and withdrawal.”

Happily, by the time Felps appears in Coyle’s book a little over a decade later, through discord generator extraordinaire “Nick” he has discovered a fourth, much more attractive option.

Finding your inner “Jonathan”

Out of the forty groups “Nick” nudged and prodded toward chaos, thirty-nine took the bait. One hold out performed well regardless—thanks to a single affable “good apple” Coyle dubs “Jonathan.”

“Over and over Felps examines the video of Jonathan’s moves, analyzing them as if they were a tennis serve or a dance step,” Coyle reports. “They follow a pattern: Nick behaves like a jerk, and Jonathan reacts instantly with warmth, deflecting the negativity and making a potentially unstable situation feel solid and safe.

“Then Jonathan pivots and asks a simple question that draws the others out, and he listens intently and responds. Energy levels increase; people open up and share ideas, building chains of insight and cooperation that move the group swiftly and steadily toward its goal.”

The whole scene plays out like some modern-day workplace version of The Screwtape Letters with the shunned temptations piling up until Nick is left “almost infuriated.”

From this, Coyle draws two lessons about “good apples”: One, though “we tend to think group performance depends on measurable abilities like intelligence, skill, and experience” and “not on a subtle pattern of small behaviors” in this instance “small behaviors made all the difference.”

Second, Jonathan “succeeds without taking any of the actions we normally associate with a strong leader. He doesn’t take charge or tell anyone what to do. He doesn’t strategize, motivate, or lay out a vision. He doesn’t perform so much as create conditions for others to perform, constructing an environment whose key feature is crystal clear: We are solidly connected.”

“Jonathan’s group succeeds not because its members are smarter,” Coyle concludes, “but because they are safer.”

“

Intent, whether negative or positive, matters.

—SHAWN MACOMBER

Developing your own personal good apple armor

Researching the “Good Apples” chapter, Coyle began to notice some of the “little moments of social interaction” that can help make a team Nick-resistant were consistent—“whether the group was a military unity or a movie studio or an inner-city school.”

It’s not as complicated as you might presume. In fact, the following sampling of simple, practical maxims from The Culture Code can get you started:

Close proximity, often in circles

Profuse amounts of eye contact

Humor, laughter

Physical touch (handshakes, fist bumps, hugs)

Intensive, active listening

Lots of short, energetic exchanges (no long speeches)

High levels of mixing; everyone talks to everyone

The message is clear: Intent, whether negative or positive, matters. The positive can win out, if it is integrated into an actionable plan and you understand what you’re up against.

At a personal level, it’s good to know the good apple need not fear the barrel. By pursuing the right thing the right way, you can transform your own team and leadership qualities for the better.