Michael Hyatt's Blog, page 54

October 31, 2017

Better Things Come to Those Who Wait

We live in an instant culture. But if we limit ourselves to fast and easy, we miss out on any wins that require patience or persistence. Honestly, most big wins fall into that second category. In this episode, we’ll share three practices to heighten your frustration tolerance and boost your stamina for long-term success.

Mind Over Marshmallow

Finally Some Good News for the Impatient

The marshmallow test is a great example of how popular social science is amplified by popular culture. Experiments that measured young children’s willpower to hold out for that second marshmallow, first conducted in the 1960s, are still inspiring TV shows today.

On Sesame Street, Cookie Monster learned to dial back the munchies so he could join the “Cookie Connoisseur’s Club”—a win for delayed gratification! In response, Stephen Colbert ended up gorging on a bag of oversized marshmallows on air—a loss!

The press reports and also distorts. In an interview with the Atlantic, the marshmallow test’s architect, Walter Mischel, had to correct one large misconception spread by the media, YouTube videos, and even the hardcover version of his own book.

The press reports and also distorts. In an interview with the Atlantic, the marshmallow test’s architect, Walter Mischel, had to correct one large misconception spread by the media, YouTube videos, and even the hardcover version of his own book.

Researchers didn’t use those large marshmallows that are often pictured, he said, but rather “teeny, weeny pathetic miniature marshmallows.” Alternately, they used tiny pretzel sticks and colored poker chips that couldn’t be cashiered.

The junior test subjects understood that the physical rewards in themselves were no great shakes. “It’s not really about candy,” Mischel explained. “Many of the kids would bag their little treats to say, ‘Look what I did and how proud mom is going to be.’ The studies are about achievement situations and what influences a child to reach his or her choice.”

One marshmallow now, or two marshmallows up to twenty minutes from now. Your call, kid. Given that simple setup, it’s almost comical the lengths to which people have gone to poke holes in the famous Stanford experiment.

Critics have argued that the sample sizes were too small or too homogenous, or that children’s trust in authority was the thing really being measured. All of which, Mischel says politely, is balderdash.

Plenty of kids, from varied backgrounds, have been tested and followed up with as adults. The examiners first established a rapport with the kids and then laid all their marshmallows on the table, so the “trust in authorities” objection is unlikely.

The objection is also misplaced. The thing that the Stanford marshmallow test accurately captured was not just willpower but the will to willpower. Those kids who could resist the urge to eat the first marshmallow right away, when they were four or five with very short attention spans and not fully developed impulse controls, grew up to be adults with more self-control than their peers, which led to greater success.

But researchers found that the kids’ self-control was not necessarily innate. The kids who held out didn’t simply have iron wills. They developed strategies to just say wait. This discovery was very exciting to Mischel, who confesses to poor impulse control himself.

The great news from the marshmallow test is that it’s not pass/fail. With some self-awareness and practice, we can learn to wait for that marshmallow. And I say this from unfortunate personal experience.

Many moons ago, I was a small investor in a not-yet-launched comic book store. I quickly gobbled down that marshmallow when I exited the partnership early over a trifling matter. Big mistake. The store has gone on to generate millions of dollars in sales—in what would have been a ten- or twenty-fold (or more!) return on my original investment.

I didn’t treat that mistake as just dumb luck but rather as poor judgment on my part, and vowed to learn from it. So long as they were playing straight with me and the fundamentals seemed sound, I decided to be more patient with future business partners, clients, and so on, going forward. That second marshmallow mindset has since served me well.

October 24, 2017

How to Avoid Career Stagnation

Effective leadership involves a commitment to personal development. Unless you continue to grow alongside your business, it will eventually outstrip you. Or worse, stagnate behind you. Join us to explore the three behaviors of high-growth leaders so that doesn’t happen to you.

5 Reasons Why I Read So Many Books

How Leaders Can Reap the Benefits of Serious Reading

I have always been an avid reader, but over the last few years, I’ve become much more intentional and ambitious in my reading. In 2015, I set my first challenging reading goal: to read fifty-two books in one year. By the time the year was done, the total was seventy-six.

I still read at least one book every week. Many people ask me, “Why read so many books?” My answer: It’s a key part of my leadership strategy. As Charlie “Tremendous” Jones said, “You will be the same person in five years as you are today, except for the people you meet and the books you read.”

My ambition is to be a better person five years from now. As a leader, I believe it is my responsibility to follow a path of personal growth. Reading is integral to that process.

Here are five reasons why I read at least one book every week:

1. To challenge my own thinking

One of my favorite aphorisms is, “Don’t believe everything you think.” We have a tendency to read books that reinforce ideas we already agree with. We’re looking for someone to confirm what we believe to be true. There is value in that. However, there is also a danger of becoming narrow-minded.

Richard Feynman, an American theoretical physicist known for his work in the area of quantum mechanics, once said, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.” That’s why I read books that challenge my thinking.

2. To learn about new ideas

While this may seem similar to the first point, it is different in a significant way. In this case, I’m not reading to reinforce or challenge ideas I already am familiar with, I’m looking for ideas I have not encountered before that sit outside my normal lanes of thinking.

I consciously select books in genres that I typically have no interest in, and very little knowledge about. It is through reading these books that I often discover the most exciting new ideas.

3. To spark new ideas of my own

Reading lots of books in different areas of thought fills my brain with concepts, ideas, and language that stimulate my own creativity. I believe that there are indeed “new things under the sun.” We discover them by taking in as many ideas as possible and letting our mind do the work of finding the connections that lead to original thinking. The easiest (and best) way I know to accomplish this is by reading lots of books.

4. To learn new practical tools for living and leading

Often, the best way to learn a new skill or procedure is to read books about that subject. For example, I just finished reading Profit First by Mike Michalowicz, a book about how entrepreneurs can make their businesses permanently profitable. This was not only a new set of ideas for me, it was a way to learn a new practical skill set to improve my business finances. After reading this book, I immediately booked a meeting with my CPA, and we made big changes in our company financial procedures.

5. To think along with the author

This is perhaps the most amazing benefit of reading, and I’m surprised that more people don’t notice it. When we read books, we’re literally thinking the authors’ thoughts along with them! The best minds in history are available to us, to help us do our thinking.

When reading their work, you can think the thoughts of Aristotle, Hemingway, John Locke, Benjamin Franklin, and countless other geniuses in their field. I can read Meditations by Marcus Aurelius and think the same thoughts as the Emperor of Rome, across thousands of years. It’s a miracle, and I never cease to be amazed by it.

“

Reading makes me a better person, a better husband, a better father, and a better citizen.

—RAY EDWARDS

These are the five reasons why I’ve read so many books (and remain committed to doing so). Reading makes me a better person, a better husband, a better father, and a better citizen. It helps me grow and develop, and to be a better leader for my team and my tribe. To me, those seem like good reasons to read great books.

My questions for you: Do you have an intentional reading plan? What are some of the reasons you read?

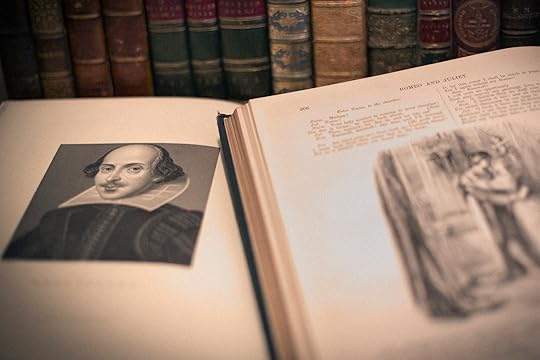

Shakespeare’s Plan for Personal Growth

What Leaders Can Learn from the Bard's Plays and Career

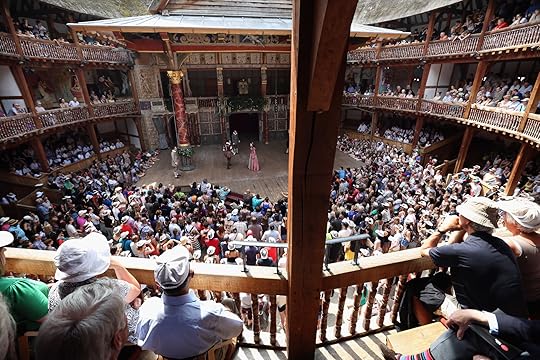

In deference to easily scandalized students, Cambridge University has begun adding trigger warnings to English classes that teach some of Shakespeare’s plays. That’s a shame if it deters participation. Students—and the rest of us—could all benefit from what the Bard can teach us about personal growth.

Declan Fitzsimons, Adjunct Professor of Organizational Behavior at INSEAD business school, points to Shakespeare’s plays as a source for insight about self-development. Whereas most characters of the time plod through their plots with little sense of development, Shakespeare’s creations are different. His characters “develop rather than unfold,” as Yale professor Harold Bloom says.

Hamlet, Macbeth, and others are all capable of surprising themselves. They express self-doubt, question their own motives, and make conscious decisions. In a monologue, or by conversing with others, they come to self-realization and change their minds and directions. And we the audience are lucky enough to observe the entire process. “Shakespeare shows us … what that development sounds like, looks like, and feels like,” says Fitzsimons.

Much of the growth Shakespeare’s work inspires lies in this discovery: at any given moment we don’t know the whole story. So we must be open to new information about ourselves or the world. (That’s the danger in potentially deterring such discovery with trigger warnings. The more insulated we are the less likely we are to grow.)

But the Bard can take us even further. It’s more than his plays that teach us about personal growth. Shakespeare’s own career as a poet and playwright instructs us as well, particularly by showing us a primary driver of personal growth: our peers.

“

Much of the growth Shakespeare’s work inspires lies in this discovery: at any given moment we don’t know the whole story.

—JOEL J. MILLER

Scholars have long noticed changes in Shakespeare’s catalog over his creative years. He developed his talent in the open, on the stage for all to see. That provides a window into how he grew as a writer. Details on Shakespeare’s life are notoriously scanty. “He is at once the best known and least known of figures,” says Bill Bryson. But it’s clear he received a solid education and was busy writing plays in London by the early 1590s.

In these early years, Shakespeare’s work was heavily imitative. In his book Shakespeare in Company, Oxford professor Bart van Es traces the influences and sources he relied upon. Shakespeare’s work was still wildly inventive, but it was because he was able to draw on a rich and varied body of work outside his own for plots, themes, and more.

But, as van Es shows, the direction of Shakespeare’s work changed in 1594 when he became a partner in the theater company, the Chamberlain’s Men. Freelance playwrights didn’t own their scripts and had almost no control over how their plays were acted (or by whom). A theater could revise their work at will and any Tom, Dick, or Harry could fill the roles. But that dynamic changed for Shakespeare when he took a share of the company.

Not only did Shakespeare do more acting himself in these years, but he began writing for the specific talents and even physical characteristics of regulars in the company. His personal relationships with actors such as William Kempe, Robert Armin, and Richard Burbage directly influenced the roles he wrote, how he structured his plays, and even the true-to-life feel of their interactions on stage. More importantly, as van Es shows, his plays are more “relational” in these years. In other words, Shakespeare’s friends and coworkers had a direct impact the direction and quality of his output.

The profound influence of Shakespeare’s peers on his growth as a writer becomes even clearer when contrasted with the third phase in his career after he stepped away from the theater in 1608. He still wrote, but the vibe of those later plays shifts dramatically; they’re less relational and more literary. The reason? He was now socializing more with writers than actors. “Shakespeare simply changed the company he kept,” says van Es.

The ultimate point, as van Es argues, is that if Shakespeare had not become a partner in the Chamberlain’s Men, his work would have developed much differently. He wouldn’t have grown into the writer he did, nor would his work have taken the shape it did.

“

For better or worse, the peers we choose impact the people we become.

—JOEL J. MILLER

The lesson here are profound. The plays show us the importance of self-inquiry, as Fitzsimons says. And as van Es demonstrates, our peers play a bigger role than we might guess. For better or worse, the people we work with affect not only our work, but ultimately the people we become.

How Our Partners Empower Our Personal Growth

New Study Reveals Link Between Self-Development and Spousal Connection

Leaders and entrepreneurs fail for a million reasons. The usual suspects include lack of cash flow, dearth of technological savvy, or insufficient planning. But according to researchers from Carnegie Mellon University, the cause behind a failure to thrive in both personal and professional settings may be much simpler to explain. At least for married folks.

In a report titled, “Predicting the Pursuit and Support of Challenging Life Opportunities,” researchers found that the decision to embrace challenging opportunities is largely dependent upon the support of a spouse or significant other. This applies to any opportunity in which one partner must jump into the unknown, weighing the risk of present discomfort or struggle against possible future reward.

“When we talk about the spousal relationship, what we are indirectly talking about is adult attachment,” explains Shanna Donhauser, a child and family therapist based in Seattle, Washington. “Humans are driven to connect with other humans in order to survive, and when we are securely attached in a relationship, we can more comfortably move about in the world. It’s not surprising, then, that people rely on their partner’s support when making challenging decisions; they need to know that they have someone on their side, in case it doesn’t work out.”

In the study, each spouse within 163 married, heterosexual couples (all married for an average of nearly ten years) was randomly assigned the role of either “partner” or “decision maker.” One week after completing a background questionnaire that assessed each partner’s typical motivations for supporting his or her spouse, the couples were then brought in to participate in a series of activities, culminating in a “challenging opportunity.”

First, the conductor of the experiment told the partner about a group of puzzles he or she would need to complete, while intentionally describing said puzzles as “fun and easy.” Then, the conductor of the experiment presented a choice, or opportunity, to the decision maker: Either work on puzzles similar to ones that his or her partner was already completing (read: fun and easy) or compete in a public speaking activity for a chance to win a cash prize.

Researchers wanted to know how the influence of the partner impacted the choice made by the decision maker. The opportunity was carefully designed to mimic real-world opportunities—particularly rising to the occasion of apparent risk.

The public-speaking challenge was “something that is available and possible to embrace, and potentially beneficial, although the final outcome is uncertain.” It also matched real-life scenarios where opting out could result in missed opportunities, such as a promotion or developing an advantageous relationship. It’s important to note that public speaking is regularly cited as a top fear of American adults, with 20 percent of the population being “afraid” or “very afraid” of this activity (according to Chapman University’s 2017 Survey of American Fears).

As expected, decision makers who received more support from their partners were more likely to choose the public speaking opportunity than decision makers who did not receive similar support. A positive connection lowered risk aversion for a potential growth opportunity.

That’s not to say that all hope is lost for those with less-than-supportive partners. Like Donhauser, Mark Henick, a mental health strategist with the Canadian Mental Health Association, notes that “a spouse can be the constant, the anchor of sorts, who helps to make an unfamiliar, insecure situation feel more safe.” But he also believes that even unsupportive, or even discouraging, spouses can become more supportive with the right encouragement.

“Open, nonjudgmental, calm conversation can help,” says Henick. “Your spouse may be anxious, too, and sometimes that can be read that as being unsupportive. If in doubt, overcommunicate. And if you’re finding that many of your conversations repeatedly result in a fight about feeling unsupported, then you may consider a trained coach or couples therapist to help you learn some skills to navigate these conversations.”

“

The decision to embrace challenging opportunities is largely dependent upon the support of a spouse or significant other.

—ANDREA WILLIAMS

Ultimately, though, an unsupportive or risk-averse partner may simply not be mature or progressive enough to recognize the upside of a business or social opportunity. What then?

“If you’re not getting the kind of support that you need from your spouse, or you need more than they can give, look for support in other places,” Donhauser suggests. “Join a group—or start one—look for online support systems, or ask a friend to help keep you accountable and supported. Creating support systems outside of your marriage can be helpful, but remember to keep your partner in the loop. Your spouse may want to celebrate your successes with you, or they may find that it’s easier to be supportive down the road.”

3 Habits of Lifelong Learners

How Leaders Can Leverage Teachability for Personal Growth

Over the years, I’ve met many influential and successful people, and I’ve observed a common trait in nearly all of them: they were all lifelong learners. If you want to win at life, this is non-negotiable. You have to become teachable. And the more teachable you are, the more successful you become.

One of the reasons for this is the more willing you are to learn, the more people want to help you. Yes, it really is true: When the student is ready, the teacher appears. And when the teacher appears, the student gets better.

So here’s how this works. If we want to become lifelong learners, committed to the practice of continually improving ourselves, we need to adopt three important habits.

Habit 1: Realize how little you know

There’s a secret that successful people know that unsuccessful people don’t know: the more you learn, the more you realize you don’t know. And if that doesn’t humble you, I don’t know what will. As Socrates once said, “I know one thing: that I know nothing.”

If you want to be a learner, you have to appreciate the fact that you have much to learn. This is not false humility or some kind of feigned status. It is a mindset. You have to continually remember how little you know and how much there is left to learn.

“

The more you learn, the more you realize you don’t know.

—JEFF GOINS

As a New York Times bestselling author, Dan Miller, likes to say, “The day I stop learning, dig a hole in the ground and put me in it because I am done.” A teachable spirit begins with a willingness to be taught.

Recently, I hosted an event where Dan spoke, and at this event, we had a workshop where we asked speakers and attendees to sit at tables and give each other feedback on any problems or struggles they were having. The idea was to give attendees an opportunity to get insights from experts in their field.

But do you know who was the first person at his table to raise his hand when I asked “Who needs some help?” None other than Dan! He may have very well been the most experienced person in that room. And yet here he was, asking for help. That’s the disposition of a lifelong learner.

Habit 2: Act like an apprentice

If you want to succeed, you have to adopt the mindset of an apprentice. There’s a reason why this subject was a major part of my two most recent books, Real Artists Don’t Starve and The Art of Work. I believe apprenticeship is a lost art that we would do well to reclaim today.

We live in an age of perceived instant mastery, where everyone wants to be an expert or a guru (and many believe they are, right away). But the truth is, excellence takes time.

When the young Michelangelo approached Domenico Ghirlandaio, the famous Florentine artist, he must have had a lump in his throat. Michelangelo was barely a teenager and was about to ask one of Florence’s most fashionable painters to train him.

When Ghirlandaio reluctantly accepted him, Michelangelo assisted the artist in whatever he needed—as a good apprentice does. Just as important as the technical skills he developed in the studio, Michelangelo also learned what it meant to be an artist: the responsibilities of running a studio, the challenges of managing apprentices, the social dynamics of dealing with patrons, and so on.

Apprenticeship is mostly watching listening, and being present in the process. You experience by doing, and you internalize those lessons. The experience led to Michelangelo getting an appointment at the Medici palace, where he met people who would support his work for the rest of his life. All because of his willingness to approach a master and offer his help.

Becoming an apprentice begins with your mindset. Long before entering Ghirlandaio’s studio, Michelangelo was practicing. He was not waiting for his Big Break; he was doing the work. That meant learning from whomever he could from an early age. He knew he wanted to be an artist and that he could not become great on his own, no matter how talented he might be. He adopted the attitude of a student, learning from anyone who could teach him.

We must do the same, offering to help the influencers and teachers in our lives in their own missions. As we do this, we will endear ourselves to these people and eventually earn them as “patrons” of a sort who help our work spread and help us grow.

Habit 3: Become someone’s case study

What we are talking about here, essentially, is mentoring. But it’s much deeper than that. Lifelong learners see everything as an education. Every book they read, every podcast they listen to, is a chance to grow and improve. And the final habit in this process is sharing what you’ve learned from those who have influenced you. This may be the best networking advice I can offer a person: become someone’s case study.

Want that blogger to mentor you? Want to get on the radar of that influencer in your industry? Don’t guilt them into doing it. You can’t manipulate or coerce your way into a relationship with your heroes. But you can win them over by simply sharing how they’ve made an impact on your life.

This is how you really earn a mentor, a modern-day master who will help you complete your unofficial “apprenticeship.” Put to work the techniques of someone you admire and demonstrate that they work. Master the principles they teach; become the apprentice they never had.

I’ve done this multiple times with bloggers, authors, and even entrepreneurs, simply reaching out with an email, saying,

Dear So-and-so, thanks for [something they helped me with], it helped me [list some measurable outcomes]. Just wanted to say thanks!

The influencers don’t always respond—after all, they are busy people—but I would say at least half of the time they do. And often these connections lead to more substantial relationships. And it all began with a thank-you, not a request to pick their brain, but simply by letting them know they made an impact.

When you do this, you make it nearly impossible for such a teacher to resist you. You’re not asking for anything. In fact, you’re demonstrating that their teaching works. If anything, they feel more invested in you, now that their techniques and reputation are on full display in you. And if you do this enough, these teachers and influencers will respond. If you honor the greats, they will honor you.

“

Lifelong learners see everything as an education.

—JEFF GOINS

The point of all this, of course, is that this is not only the best way to succeed in the work we do. It’s the best way to live. To always act like an apprentice, never assuming we know too much (because we really don’t). To find masters and teachers wiser than us (even sometimes younger than us) who can show us the way. And then to ultimately put that advice to good use and see the fruit of that wisdom.

Lead to Win Podcast, Episode 1

4 Practices to Become a Self-Aware Leader

When a high-performer encounters a startling career setback—perhaps getting fired or passed up for a promotion—the culprit is easy to predict. Nine times out of ten, it stems from a lack of self-awareness.

Understanding your shortcomings is a prerequisite for correcting them. That’s why your level of self-awareness has the power to either slow your growth or skyrocket your success.

This is the final episode on the This is Your Life feed.

For future episodes of the podcast, search for Lead to Win or visit www.leadto.win.

October 16, 2017

4 Practices to Become a Self-Aware Leader

When a high-performer encounters a startling career setback—perhaps getting fired or passed up for a promotion—the culprit is easy to predict. Nine times out of ten, it stems from a lack of self-awareness. Understanding your shortcomings is a prerequisite for correcting them. That’s why your level of self-awareness has the power to either slow your growth or skyrocket your success.

Why You Need to Hit Pause to Keep Moving

4 Simple Steps to Stay Self-Aware, Even During the Craziest Day Ever

After conducting an in-depth study of seventy-two high-performing CEOs, Cornell University researchers reached a surprising conclusion. The key predictor of success for leaders wasn’t grit, focus, education, decision-making skills, a knack for strategic planning, or even IQ. It was self-awareness.

Many experts would say self-awareness is simply the ability to monitor and regulate our thoughts, feelings, and actions (and the effect they have on ourselves and others). I half agree. In my experience cultivating and practicing self-awareness requires we identify and challenge the bogus unconscious beliefs underlying the ways we think, feel, and act.

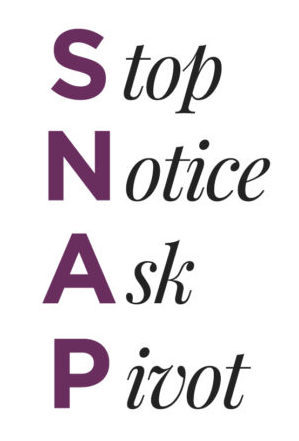

While writing my book The Road Back to You, I devised a practice to help people surface and neutralize their self-limiting beliefs. Based on the acronym SNAP, this practice has helped me wake up to know when self-limiting beliefs have taken the helm of my life. Here’s how SNAP works.

1. Stop

Every four hours a notification comes up on my iPhone reminding me that it’s time to stop for two or three minutes to give my full attention to whatever’s happening in my life at that precise moment. Sounds easy, right? Forget it. Everything in our frenzied, goal-oriented world militates against pausing even for a few minutes to switch off autopilot, and consciously come home to ourselves. But we can.

To stop, take four or five deep, prayerful breaths to ground yourself in your body and return to the present moment. The purpose of this step is simply to wake up and bring your awareness back to your immediate experience.

2. Notice

Often we get swept up in the rush of daily activities and habitual reactive behaviors, but rarely do we step back to observe and learn from them. Once we’ve come to a full stop, we look around to see what we’ve been missing while we were lost in our thoughts or absorbed in our work.

Is the environment around us calm, or burning to the ground? How are we connected to what’s going on? Are we personally in a good space, or do we notice we’re caught up in outmoded, habitual perspectives and behaviors?

Whatever you discover, make sure as you notice or observe what you’re feeling, thinking, and doing in the moment that you do so with compassion! No labeling, analyzing, criticizing, or trying to fix anything. Your job right now is to simply notice, nothing else.

3. Ask

Now that you’re awake to what’s happening in the moment, you can ask yourself three questions that will expose any self-limiting beliefs and get you back on track if you need it. Let me illustrate how these questions work with an example from my own life.

Once, while working against a tight book deadline, I came down with a case of writer’s block. I stared at the blank page on my computer screen for hours until I became an anxious wreck.

Then the notification on my iPhone came up reminding me to stop and practice SNAP. Stopping work was the last thing I wanted to do given how far behind I was, but I yanked myself away from my computer, and asked myself the first question: “What am I believing right now?”

This is a powerful question. After only a few minutes of quiet reflection, the unconscious beliefs fueling my anxiety and writer’s block surfaced.

“Everyone from my agent to my dog will feel irreversibly disappointed in me if this book doesn’t hit a bestseller list.”

“People only value me for my work and accomplishments in life, not for who I am, so this book better be a masterpiece.’”

“The world only loves people who succeed. No one loves a loser.”

How’s that for crazy thinking? Is it any wonder my creative well dried up when beliefs like these were swimming just beneath the waterline of my consciousness? Depending on your particular work, you can probably substitute any number of other bogus notions you might harbor any given day or hour.

“

We must identify and challenge the bogus unconscious beliefs underlying the ways we think, feel, and act.

—IAN CRON

I then asked myself the second question, “Are these beliefs true?” Of course, not! As a therapist, I know these perceptions are rooted in old personal narratives and have no basis in reality. This doesn’t mean the archaic scripts of our past don’t occasionally get loose and wreak a little havoc in our lives.

Finally, the third: “How would my life change if I let go of this belief?” This last question wasn’t hard for me to answer. Once free from these over-exaggerated, fear-based beliefs I could write the book I was supposed to write rather than feel the paralyzing pressure to write the next War and Peace.

4. Pivot

And that’s what I did. Once I’d identified and interrupted the circuit on my bogus beliefs I was able to pivot and make different, healthier, more helpful choices that were in line with the truth. Not long after I practiced this SNAP exercise I was able to get back to work and made my deadline, albeit with minutes to spare!

It’s impossible to overstate how important it is for leaders to grow in self-awareness, to recognize and challenge their mistaken unconscious beliefs which, left on their own will undermine their best efforts to become the healthiest version of themselves.

It’s impossible to overstate how important it is for leaders to grow in self-awareness, to recognize and challenge their mistaken unconscious beliefs which, left on their own will undermine their best efforts to become the healthiest version of themselves.

“Your beliefs become your thoughts, your thoughts become your words, your words become your actions, your actions become your habits, your habits become your values, your values become your destiny.”

Need I say more?