Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 37

August 5, 2022

From the Archives: Word with a Past: Maffickj

The Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) started badly from the British point of view. British troops, supposedly the best trained and best equipped in the world, suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of Boer farmers. (Anyone else hear echoes of another colonial war that pitted farmers against British regulars?)

The only bright spot in the morass of inefficiency and disaster was Colonel Robert Baden-Powell’s spirited–and well-publicized–defense of Mafeking, a small town on the border between British and Boer territory. (Yep. The guy who founded the Boy Scouts.)

The siege lasted for 219 days. Undermanned and inadequately armed, Baden-Powell improvised fake defenses, made grenades from tin cans, and organized polo matches and other entertainments to keep the garrison’s spirits high. The British public was able to follow “B-P’s” defense of Mafeking because the besieged town included journalists from four London papers, who paid African runners to carry their dispatches through the Boer lines.

When news of the garrison’s relief reached England, public celebrations were so exuberant that “maffick” became a (sadly underused) verb meaning to celebrate uproariously.

Maffick vt. To celebrate an event uproariously, as the relief of Mafeking was celebrated in London and other British cities.

So, have you mafficked something recently?

This post originally ran on June 21, 2011.

August 2, 2022

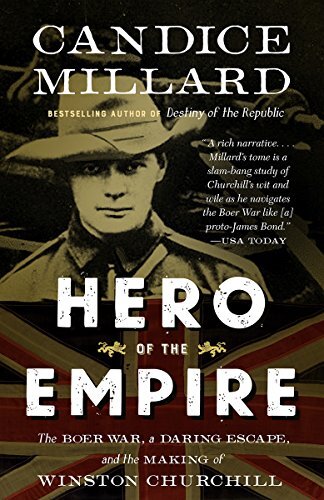

Hero of the Empire

I don’t always get to books when they first come out.* And that’s not a bad thing. Speaking as a writer, I want people to continue to find and read my books long after their publication date.** Speaking as a reader, I love digging into the backlist of authors who have newly crossed my path.

All of which is a long way of saying I recently pulled Candice Millard’s Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill off the shelves where it has aged since it’s release in 2016. And is so often the case when I am late to the party, I wonder what took me so long. Because it is so very, very good.

Hero of the Empire is a slice-of-life biography: it tells the story of Winston Churchill’s capture by the Boer army in 1899, his escape, and his journey to safety through hundreds of miles of enemy territory, with a great deal of reliance on the kindness of strangers. Millard puts the story in the context not only of the Boer War but of Churchill’s overweening ambition. She tells the story of the escape with as much building tension as if it were a thriller—quite a trick when the reader knows full well that Churchill will succeed. (Though now that I think about it, in most thrillers we know that the hero will succeed, or at least survive. What keeps us reading is the how, not the what.) And she convinces us that this seemingly small, and in many ways totally unnecessary, incident in Churchill’s life has important repercussions for Britain’s morale at a demoralizing moment in the Boer War as well as for Churchill’s own career.

If you want a measure of just how good this book is: I am not a Churchill fan. And none of his actions in the book did anything to make me like him more than I did going in. In fact, I may have ended the book with less respect for Churchill as a human being than I had going in. And yet Millard kept me fascinated, page after page.

Her newest book, River of the Gods: Genius, Courage and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile*** is already on my TBR pile.

* What can I say? The To-Be-Read shelves runneth over and at any given moment I am juggling 10 or 12 Big Fat History Books related to the book I am currently writing.

**And I am happy to say that they do. Yesterday I got an email from someone who had just finished my book on socialism, LINK which came out in 2011. (This is the way to make an author’s day.)

***About Richard Burton, the explorer. Another man I have significant doubts about.

July 26, 2022

Road Trip Through History: The Littleton Brothers Memorial

Moving south along the river, we stopped to visit the Toolesboro Mounds site, outside Wapello, Iowa, because I am a sucker for the Mound Builders and My Own True Love is a good sport. The site was interesting enough, but it paled in comparison to a memorial across the street.*

The Littleton Memorial is a privately maintained monument to the Littleton brothers, six brothers who died in the American Civil War. They are the largest single group of siblings known to have died in any single American war. One died in battle. One died of wounds sustained in battle. Two died of the illnesses that plagued army camps. One died at Andersonville Prison while a prisoner of war. One died as a result of an accident during troop movements. In some ways, their deaths present a microcosm of America’s losses in the war.

A descendant of one of the brothers was tending the grounds when we stepped across the street to look at the monument and we had a chance to talk to him. It turns out that the story of the memorial is as interesting as the story of the brother. At least to those of us who are interested in how history is preserved.

It turns out that the family had forgotten the story. It came to light again in a variation of the “lost documents in the attic” that every historian dreams of. A woman named Olive Mary (Kemp) Carey who was born in the area, subscribed to the local paper for her entire life as a way to keep in touch with her hometown. In 2010, her family reached out to the local historical society to see if any one was interested in her scrapbook. Someone there rightly said “Hell, yes” “yes please.” Going through the clippings, a member of the found a “Local History” column from 1907 talking about men from the county who had served in the war, including the tragedy of the Littleton family.

It took a lot of work to get from that clipping to today’s monument to loss and memory.

*In all fairness, The Toolesboro Mounds interpretive center does a very good job in a limited space of describing what we know about the Hopewell culture . It does an even better job of describing the discovering of the Toolesboro Mounds in the mid-nineteenth century and the changing relationship of archaeologists to the mounds over time. (It will not surprise you to learn that I was particularly taken with the career of Mildred Mott Wedel, 1912-1995, one of the women to work as a professional archeologist.) Not much new if you are familiar with mound builders sites, but a good introduction if you are not.

——————

Traveler’s Tip:

If you are in Burlington Iowa for breakfast, I highly recommend Jerry’s Main Lunch, where their motto is “No great adventure ever started with a salad.” The posted menu is limited, but within minutes of ordering the “regulars” fitted next to us at the counter let us know that there were lots of “secret” variations available. I ordered the original “hot mess”. It was so delicious that I’d have gone back for lunch if we hadn’t been on our way out of town.

July 19, 2022

Edith Wharton’s Morocco, A Literary Pilgrimage, a guest post by Stacy Holden

Today I’m going to give you a little break from the Great River Road. We’re still going to be on the road, just further afield. Morocco in fact, courtesy of writer, historian and traveler Stacy E. Holden.

Stacy is a history professor at Purdue University. Her published works focus on everyday life in the Arab world as well as Western representations of the Middle East and North Africa. She has written on historic preservation, UNESCO heritage sites, and even post-9/11 romance novels set in imaginary Arab kingdoms. She is now working on a book about how Edith Wharton shaped American attitudes toward the Middle East and North Africa.

I don’t remember who introduced us to each other, but thank you whoever you are. We’ve been talking about history, writing, and travel ever since.

Take it away, Stacy!

In 1917, Edith Wharton traveled to Morocco for five weeks, and three years later she published In Morocco. Even today, her travel account reads like “Top Ten Things To Do in Morocco 2022.”

When Wharton disembarked in Tangier, this North African kingdom had been a French colony for only five years. In Morocco was the first account of colonial rule in Morocco by an American author and for an American audience. This information is key to understanding the importance of this book. Wharton backs French colonial rule, even though the US, first under Republican President William Howard Taft and then Democrat Woodrow Wilson opposed France’s imperial expansion.

Wharton was an official guest of the colonial administration, and French scholars and officers accompanied her everywhere she went. They took her to colorful bazaars and spice markets, medieval mosques and ancient mausoleums, walled cities of the premodern era, and even a purported pirate lair. Wharton’s traveled southward from Tangier, stopping in Ksar el Kabir, Rabat, Salé, Casablanca, Meknes, Volubulis, Moulay Idriss and Fez before reaching Marrakesh, her ultimate destination.

The travelogue appeared in bookstores three years after her trip, in November 1920. The Age of Innocence was also published that month, a novel that secured Wharton’s literary fame. The fictional account of Gilded Age Society in New York City epitomizes Wharton’s keen eye for small details.

But if observation were a superpower, Morocco would be Wharton’s kryptonite. Her first-hand account of Morocco conveys a fantasy. Instead of realistically portraying life in colonial Morocco, Wharton claims, “Everything that the reader of the Arabian Nights expects to find is here.” She never discusses the hardships of colonized Moroccans or the war in Europe. Instead Wharton refers all-too-often to djinns, flying carpets, harem ladies, and “a princess out of an Arab fairy tale.”

As a professional historian, my research focuses on the modern Middle East and North Africa. I have traveled back and forth to Morocco since the late-1990s and lived full-time in Rabat, the capital, between 1999 and 2002. My travels have led me to read and visit all the sites Wharton describes.

Wharton’s travelogue does not accurately portray life in Morocco—her descriptions are fantastical and often false—yet Wharton fans and scholars should not neglect this work. In Morocco sheds light on what made Wharton tick as a writer, why she endorsed French imperialism, and how literary figures like Wharton—a woman without a government position—shaped American ideas about the world.

Amanda Mouttaki and I have decided to organize a ten-day tour of Morocco together, retracing Wharton’s footsteps. Amanda is a travel planner based in Marrakesh, and our trip merges her expertise in tourism with my own knowledge of American literature and Moroccan history.

Morocco is my “second home,” and I want to share my knowledge of it with travelers interested in the experiences of Edith Wharton and the history of the Arab world.* I also look forward to conversations with travelers, who, with their fresh sets of eyes, raise unexpected questions that can foster interesting conversations and thus allow me to reflect and process information in new ways.

At the end of the day, I hope we can all sit down and talk about what Wharton said in In Morocco. She wrote, “Everything that the reader of the Arabian Nights expects to find is here.” By the end of our ten-day tour, you will be as able to explain and critique this statement as I, merging knowledge of local sights, Wharton’s life and travels, and critical analysis among member of our small group.

For more information, you can click on this link. I look forward to seeing you in November 2022.

*Don’t get me wrong, there will be time for decompressing poolside with mimosas.

[Pamela here: I would sign up for this trip in a heartbeat if I didn’t have a book deadline hanging over my head.]

July 16, 2022

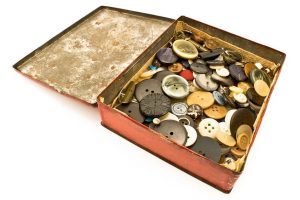

From the Archives: Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button?

We drove through Buffalo Iowa early on a Sunday morning, just as Judy’s Barge Inn, a local variation of the more common Dew Drop Inn, was opening for the breakfast crowd. It was too early for a local historical society to be open. It was not too early to stop and read the local historical marker, which reminded us that Buffalo, like other small towns along this stretch of the Mississippi was part of the nineteenth century’s button boom, which we learned about in 2019 during an earlier trip on the Great River Road.

The nineteenth century button industry based on fresh-water mussels was a recurring theme of our ten days on the Great River Road this year.

In 1891 a German button manufacturer named John Frederick Boepple opened a button factory in Muscatine, Iowa, after a change in tariff laws caused his business in Germany to fail. Shell buttons weren’t new. The Boepple family had made buttons from shells and horn for many years. But the plentiful mussel shells found in the Mississippi River near Muscatine were thick and well suited for cutting into buttons.

At the time that Boepple opened his small factory, the McKinley tariff of 1890 meant that imported shell buttons were expensive. The original foot-operated lathes that Boepple adapted from those used to make buttons from ocean shells were designed to allow skilled craftsmen to create a button from beginning to end, which meant that even without the additional cost of the tariff buttons were not cheap.* With the introduction first of steam-powered lathes and then a revolutionary machine called the Double Automatic that, well, automated the process, attractive mother-of-pearl buttons were affordable to the average household. By the late nineteenth century, buttons made from river mussel shells were so popular that bars in at least one river town accepted mussel shells as payment.

Like other industries along the Great River Road, buttons were a boom and bust business. “Clammers” earned good livings harvesting shells from the river in large quantities. Button factories sprang up in towns up and down the Mississippi, creating hundreds of factory jobs and more opportunities for cottage industries where women and children sewed buttons to cards at home. In the same way that the logging industry overcut the great forests of Minnesota and northern Wisconsin, by the 1920s, the button industry had decimated the Mississippi’s mussel population, and precipitated its own demise.**

* Today we tend to think about buttons as nothing in particular. Or more accurately, unless you knit or sew, you probably don’t think about buttons at all unless you have to sew one back on your jacket. (A skill everyone should learn, in my opinion.) But historically buttons were a luxury item: made by hand and often from expensive materials. It turns out there was a good reason my grandmothers (and probably yours) kept a button jar. (For that matter, I still have one.)

For those of you who’d like to know more, I recommend this article:

http://www.slate.com/articles/life/design/2012/06/button_history_a_visual_tour_of_button_design_through_the_ages_.html

** The related story of efforts to restore the river mussel population was also a recurring theme of our trip. At one time there were 51 species of mussels in the upper Mississippi; today theater are 38, eighteen of them endangered.

July 12, 2022

Road Trip Through History: The Putnam Museum

My Own True Love and I make a point of visiting local historical museums whenever we’re on the road.* What a museum choses to focus on can tell you how a community or a region defines itself. Even a museum that seems at first glance to be an uncurated (or as autocorrect intriguingly suggests, uncharted) collection of stuff tells a story with the choices it makes.

The Putnam Museum in Davenport is an excellent example of the hybrid natural history/history museum that we occasionally find in smaller cities. As always, the combination is a reminder that a region’s natural history is the basis on which its human history is built.

We spent our time in the museum’s two major exhibits.

The first, titled Black Earth Big River, focuses on the natural history of the area, beginning with the different habitats that make up the area and ending with today’s small city version of an urban environment. I was fascinated by the exhibits dealing with prairie grass and the creation of black earth, which the exhibit dubbed “prairyerth.” This exhibit was a useful counterpart to the story of John Deere’s creation of the self-scouring steel plow: the root patterns of prairie grass are pretty amazing. (Take a look at the illustrations in this Nat Geo piece: Digging Deep Reveals the Intricate World of Roots )

The second, titled River, Prairie and People, began with the geographic history of the region, and then followed the history of humans in the region from the earliest peoples who reached the region through the mid-twentieth century. I was pleased to see a sign at the front of the exhibit asking visitors to help make the museum more inclusive and drawing attention to signs throughout the exhibit marked “New Content,” all of which added stories about women and people of color in the Quad Cities.** In at least one case, a “New Content” sign fleshed out a reference in an existing exhibit, allowing an important woman to appear in her own right who had previously been referred to only as her husband’s wife.

Three stories in particular caught my imagination:

Alexander Brownlie and his brothers, who were trained masons, created a unique form of sod house. Most sod houses, known as soddies, were made from mats of sod. The Brownlies pounded sod into molds and created firm blocks that were essentially sod bricks. They used them to create sod and clay walls that were a foot thick and could support a two story structure. Luxury living on the prairie!During World War II, children collected 25 million pounds of milkweed pods, which were used to fill 1.2 million military life vests. Twenty-six ounces of milkweed floss could keep a 150 pound soldier afloat in salt water for 48 hours. That is a LOT of milkweed.

Image courtesy of Stephen Williams – https://phrontistery.info/para/a05/a0...

In 1877, amateur archeologist Rev. Jacob Gass discovered three inscribed slate tablets in a local burial mound. The tablets, which were inscribed with what he took to be characters of an ancient language depicted a cremation scene, a hunting scene, and an astronomical calendar . Gass believed they were proof that the mounds had been built by an ancient people of European ancestry rather than Native American peoples.*** The Davenport Tablets were initially hailed as an American Rosetta Stone, but scholars, including a team from the Smithsonian, soon began to look at them more carefully, using new techniques that would help change the nature of archeological study. The final consensus was the the tablets were frauds. Oddly, there is reason to believe that Gass was the victim of the fraud, which was perpetrated by members of the Davenport Academy of Sciences as a way to embarrass Gass. Which seems like an odd thing for adult scientists to do.

* In fact, my love affair with local historical museums dates from high school. My friends and I hung out at the local historical museum the way the kids from Happy Days hung out at Al’s Diner. But that’s a whole different story.

**This is becoming more and more common in the museums we visit, and I, for one am mighty happy to see it.

***A popular idea at the time. And by European, they meant ancient Egyptian. Don’t get me started.

July 5, 2022

Rock Island Arsenal, Pt 2 Taming the Mississippi

As so often happens on our road trips, our visit to the Mississippi River Visitor Center at Lock and Dam 15 on Arsenal Island turned out to be much more than we expected.

We went to the center expecting to see exhibits on the flora and fauna of this stage of the river, the general history of how the Corps of Engineers made (and keep) the Mississippi navigable, and the specific history of Lock and Dam 15.* At most, we hoped to see a boat go through the lock—eternally fascinating as far as we are concerned. (Though not quite as magical as watching a blacksmith at work.)

In fact, the vistors’ center had all of that, including what turned out to be a detailed topographical map of the area around the lock and dam on the first floor of the center, with a clever way to display the map’s scale. (Turns out I have a six-mile foot. Who knew?)

We would have been perfectly happy with all of the above. But when we walked in, the ranger on the desk asked “Are you here for the tour?” We were not. When she asked if we would like to join, we did not even have to confer with each other. The answer, obviously, was yes.

Once again, we had an enthusiastic and knowledgeable volunteer guide. He talked about how the lock and dam worked, the unusual bridge that links Arsenal Island to the Iowa side of the Mississippi and its predecessors, and the role Fort Armstrong played in the American Civil War. We got to see boats go through the lock, and a close up look at the bridge swinging open to accommodate the process. (We also got a close up look at water running over the dam, and the bright yellow “last chance ropes” suspended from the bridge. Together they emphasized just how dangerous the dam is.)

Here are the bits that caught my imagination:

Rock Island was the site of the first railroad bridge to cross the Mississippi. The bridge was finished in April, 1856. Two weeks after it opened, the steamboat Effie Afton hit one of the bridge’s pillars. Both the steamboat and the bridge caught on fire. The Effie Afton sank. The Illinois side of the bridge collapsed onto the wreck of the steamboat the next day. The trial that followed played an important role in the conflict between riverboats and railroads over which technology would control access to the west—not an insignificant issue at the time. (It also had a role in the career of a little known Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. )Government Bridge has two layers: the top layer is a railroad bridge and the lower lay was originally for horse drawn vehicles. Which seems wrong. After all, trains are heavier than horse drawn vehicles, and you always put the heavy stuff on the bottom for balance. However, it turns out that horses are freaked out by having trains go under them. Who knew?The bridge is now painted with radar resistant paint for security purposes. Which somehow struck me as funny.

*Because every lock and dam on the river has its own story that begins with the river conditions at a certain spot.

Travelers’ Tips.

For those of you who did not read the last post here on the Margins,# Arsenal Island is home to the Rock Island Arsenal and the district headquarters of the Army Corp of Engineers Since the Arsenal is an active military base, you need to get a pass to get to the welcome center. (Unless you have a military id.) Take the bridge from Moline—not the bridge from Davenport—and follow the signs to the Visitor Control Center. You will need a valid state id or U.S. Passport.

There are public tours of Lock and Dam 15 on Saturdays. However, you can schedule a tour at other times. The website says you need a group of ten or more people, but the tour we joined up with was originally a group of two. You don’t know until you ask.

#Not pointing fingers. I realize you have many choices about things to read, on line and off, and I appreciate any time you choice to spend with me.

June 28, 2022

Rock Island Arsenal, Part 1: Colonel Davenport’s House, and a Couple of Long Digressions

Visiting “Colonel” George Davenport’s house on the Rock Island Arsenal* turned out to be more interesting than I expected, in part because of our knowledgeable and enthusiastic guide. And also because it turned out that “Colonel” Davenport was right at the center of things in the history of the the region. Something I also hadn’t expected. (Somehow it didn’t dawn on me until our visit that the city of Davenport was named after him. *Duh*)

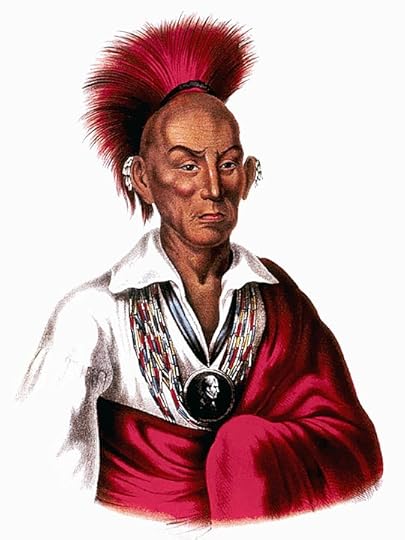

George Davenport, ca. 1845

Davenport was a British sailor who came to the United States on a British ship in 1783, after the Treaty of Paris, which in theory resolved issues between Great Britain and its former colonies.** Shortly before the ship set sail from New York back to Britain, one of Davenport’s fellow sailors fell overboard. Davenport jumped in after him, breaking his own leg in the process. Because a sailor with a broken leg was of no use on board ship—and possibly an active liability—Davenport as left behind when the ship sailed.

Instead of finding his way back to Britain when his leg healed, Davenport decided to settle in the United States and joined the American army. He served for ten years, working his way up to sergeant. He served during the War of 1812, fighting against the British and mustered out at the war’s end.***

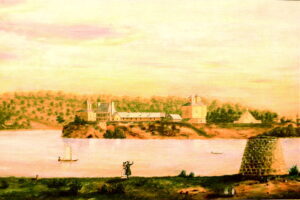

During the War of 1812, the American army lost two skirmishes with Native American allies of the British in the area of the Upper Rapids, a difficult part of the Mississippi River between the modern towns of Davenport and Le Claire.**** Concerned about continued relationships between the Sauk and Meskwaki peoples and Canada, the Army decided to build an outpost on Rock Island—a location that would allow them to command the Upper Rapids and give them easy access to both the Sauk city of Saukenak and two nearby Meskwaki villages.

Fort Armstrong

Davenport accompanied the army as the post sutler: a civilian contractor responsible for providing the army and its builders with everything they needed. He also made a claim on a substantial amount of land on the island and built a log cabin for himself and his family. His wife Margaret and her two children from a previous marriage came with him. (As an aside: There is no proof that Margaret and George were married and lots of speculation about their relationship. He publicly acknowledged Margaret was his wife, but she was 14 years older than he was and Davenport openly had two sons with her daughter Susan. Lots of questions, no good answers. )

By the time Fort Armstrong was completed, Davenport decided it was time to move on to a more lucrative endeavor. He got a fur trading license and developed a network of posts that ranged from Galena down to southern Iowa and west to Des Moines, with his base at Rock Island.

When the Black Hawk Wars began in 1832, the governor of Illinois appointed Davenport quartermaster of the Illinois militia and gave him the rank of Colonel—no doubt for reasons that made sense to the governor. Despite the fact that the historic site is called the “Colonel Davenport house,” Davenport does not appear to have used the title after the war. Perhaps he agreed with Eddie Rickenbacker that you shouldn’t use a title you hadn’t earned.

In 1833, Davenport built the house that we toured, which is roughly contemporary to the house at the John Deere historic site. The most interesting thing about it as far as the architecture is concerned is that though it looks like a frame house, the main part of the house is a two story log cabin with clapboard siding. (Lumber was expensive on the frontier.)

In the meantime, things were changing in the territory around the Upper Rapids and Davenport was involved in all of it. He gave up his fur trading license and focused on trading with members of the growing white population in the region. He piloted the first steamship upriver through the Upper Rapids, helping open the northern section of the river to the steam boat trade. Then he sold cord wood to steamships heading up the Mississippi. He was instrumental in establishing the towns of Rock Island and Davenport. And he was one of the movers and shakers involved in founding the Rock Island Line: a 75-mile long railroad that linked Rock Island with Chicago.

Davenport did not live to see the railroad come to fruition He was murdered in his home on July 4, 1845. Drawn by rumors that he had at least $20,000 in his safe, several would-be thieves broke into the house during the 4th of July celebration in Davenport. They assumed the house would be empty. Unfortunately, Davenport was not feeling well and decided to stay home. The robbers shot him in the leg, and then forced him to open the safe. When they discovered that it contained only $400, they beat him unconscious and left him for dead, taking a few small valuables with him.

Davenport revived and lived long enough to give a description of his robbers before he died. Five men were captured and charged with his death.

* Just to make it clear, there are two Rock Islands in the Quad Cities area. One is the city of Rock Island, Illinois. The other, technically Arsenal Island, is the largest of three river islands in the area and home to the Rock Island Arsenal. Unfortunately, most people still call Arsenal island by its former name of Rock Island, leading to confusion among the uninformed.

**As is so often the case, the treaty left significant issues unresolved. Hence, the War of 1812.

***During the course of our visit, I found myself wondering whether Davenport ever became an American citizen. Our guide didn’t know, and on discussion we realized that neither of us knew how a person became a citizen in the first decades after the United States.

I knew from an earlier project that at the time the British defined an American as someone who lived in the thirteen colonies prior to 1783 or who was born there. They did not recognize the right of a British emigrant to become a citizen of a new country. (In other words, from the British perspective, Davenport remained a British citizen until the day he died.)

The United States recognized the need for a naturalization process almost from the start. Congress passed the first naturalization act on March 26, 1790. The act provided that any free, white, adult alien, male or female, who had resided in the United States for 2 years was eligible for citizenship and could apply for citizenship to any court of record. (The naturalization process was finally opened to African immigrants in 1870.)

None of which answers the question of whether Davenport became a citizen.

****One of those skirmishes occurred on Credit Island, so called because it was the place where French fur traders negotiated how much credit they would give Native American hunters in the fall against furs to be hunted over the winter, and where they later settled accounts with those hunters. A colonial relative of two addresses that caught my eye during a recent visit to an Atlanta suburb: Cashback Bonus Boulevard, near Credit Card Court. I cannot make these things up.

__________________

Traveler’s Tip:

The Davenport house is located on the Rock Island Arsenal, which is an active military base. You need a pass to get on base unless you have a military id. Take the bridge from Moline—not the bridge from Davenport—and follow the signs to the Visitor Control Center. You will need a valid state id or U.S. Passport.

Give yourself plenty of time. (As far as I’m concerned, this is always a good idea no matter what you’re doing.) There may be a line.

June 21, 2022

Road Trip Through History: Black Hawk State Historical Site

My Own True Love and I are big believers in stopping at the local tourist information center in any town we go through, even if we are simply in transit rather than on an official Road Trip. More than once, a local booster has steered us to something we might not have found on our own. The Quad Cities tourist information center in Moline did not disappoint.*

Once she learned that we were interested in history, the young woman at the information desk insisted suggested strongly that we visit Black Hawk State Historic Site, just outside Rock Island, Illinois. She assured me that the park’s museum covered more than just the Black Hawk War, which we had already spent a great deal of time thinking about on our last trip along the Great River Road.** In fact, she patiently assured me of this several times because I could not quite believe it was true.

It turns out that she knew her stuff. From the history buff’s perspective, the site is a two-fer.

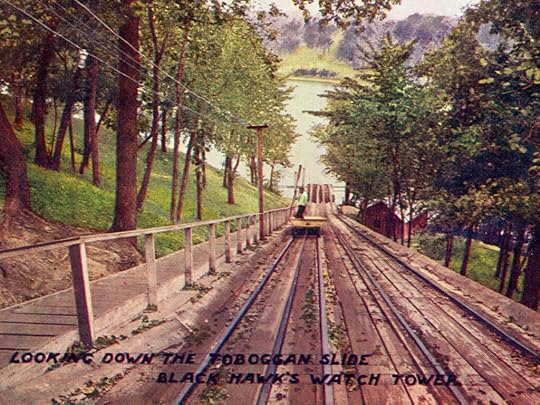

The park itself was the site of the Watch Tower Amusement Park, which operated from 1891 to 1925. Operated by the local street car company, the park was located at the end of the line. (Admission was free if you came on the streetcar.) The park had everything you would expect at amusement park, including a 1,000-seat amphitheater where traveling theater troupes of all kinds, from opera to vaudeville, performed. Thousands of people visited the park each day

The most popular ride was called “Chute the Shoots”: the prototype for the toboggan slide rides that became popular in amusement parks across the country within a decade. Flat-bottomed boats ran on greased wooden tracks from the top of a steep bluff down to the Rock River, gathering speed along the way. (Up to 80 miles an hour according to one source.) When the boat near the bottom of the track, the ride’s operator released the boat from the tracks, which then skimmed over the water. The conductor would pole the boats back to the bottom of the Chutes, where they were hauled back up using electricity from the street car lines. Personally, I think it sounds terrifying. But then, the Tilt-a-Whirl is the wildest ride I’m willing to go on.

In 1925, the Tri-City Railway closed the park which had become too expensive to run. In 1927, the State of Illinois purchased the site, removed the rides and attractions, and created Black Hawk State Park.

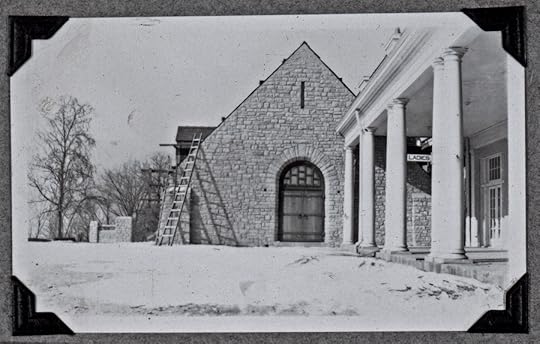

The amusement park was a lagniappe as far as we were concerned. We were there for the Hauberg Indian Museum, which is housed in a located in a massive stone and timber lodge built by the Civilian Conservation Corps.(Though in truth, we are always happy to wander around a CCC building. And this one is a stunner.)

The a small museum focuses on the Sauk and Meskwaki*** peoples. The first room tells the history of the two nations from the time they settled in the region in the mid-18th century through the Black Hawk war, which was the heart of the museum as far as I was concerned. The second room contains a set of four life-size dioramas depicting the live traditional lives of the two nations across four seasons—which I wasn’t particularly interested in—and photographs of some of Black Hawk’s descendents—which I found fascinating.

Here are the things that stuck with me abut the years before the Black Hawk War:

The Sauk (or Sac, depending on who you read) and Meskwaki were Algonquin language people who arrived in the area near what is now the Quad Cities around 1760. They had been forced out of their home in the Great Lakes region as a result of fur trading conflicts with the Huron. In turn, they forced the Illini Confederation peoples west out of the Rock River Valley.Both peoples were semi-nomadic, occupying permanent settlements during the growing season and hunting and trapping furs during the winter to trade for supplies. The Sauk lived south of the Rock River in a city called Saukenak. With a population of some 5,000 people, it was the largest city in Illinois at the time of the 1822 census. The Meskwaki lived in several smaller villages that were built 25 to 30 miles apart, about one hard day’s ride on horseback. Saukenak was the site of the westernmost battle/skirmish/conflict of the American Revolution. Colonel George Rogers Clark ordered an expedition against the Sauk city in retaliation for Sauk support of the British. A small force of American, French and Spanish soldiers destroyed the city. The Sauk rebuilt Saukenak, only to have it attacked again in 1814. Black Hawk was thirteen when the city was destrtoyed.Perhaps it should come as no surprise that he was not a fan of the United States.* For those of you who aren’t from the Midwest, and maybe for some of you who are, the Quad Cities are four small cities clustered around the banks of the Mississippi. Moline and Rock Island are in Illinois. Davenport and Bettendorf are in Iowa. (Personally, I always have trouble keeping them straight in my head.)

**Not enough time to be considered experts, but definitely more than a casual glance. (Are there Black Hawk War buffs?)

*** The French called them Reynards (Foxes), for reasons that I have not been able to discover, and they show up as the Fox people in many English language accounts. But that is not what they called themselves, and there is no reason we should continue the practice. You could call me Patsy, but it wouldn’t make it my name.

_________

Travelers’ Tips:

• If you put the official park address in your GPS, it will take you to the park office. The woman at the office made it clear that she was with the conservation police and knew nothing about the museum. She did, however, offer to issue me a fishing license. If you are at the site for history-buff reasons, you want to stop at the Watch Tower Lodge, which appears to be closed. Drive past the locked gates and follow the sign to the parking lot.

• Try the ice cream at Largomarcino, in Moline. They’ve been making their own ice cream in the basement since 1908 and it is fabulous.

June 16, 2022

From the Archives: The So-Called Black Hawk Wars

Normally when one of my posts refers to circumstances that I wrote about in the past, I simply put a hot link in the new post referring any readers who are interested back to the old post, with no assurance that anyone other than My Own True Love will click through.

But the Black Hawk War—which I now think of as the Black Hawk Massacres—is a recurring theme in the next few posts. Some of you might find this post from 2019 helpful. (And if you don’t, I’ve found it useful to re-read it. Because details fade when you don’t reinforce them.)

* * *

Here’s what I knew about the Black Hawk War at the beginning of our most recent travels along the Great River Road: it was a small scale war between Native American tribes and American settlers in the upper Midwest prior to the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln fought in it as a member of the Illinois militia. I didn’t even known which tribes were involved.

It soon became clear that the war would be one of the recurring themes of the trip. We drove on Blackhawk streets and across a bridge named in honor of Chief Black Hawk. His picture appeared with brief paragraphs in the displays at Effigy Mounds National Monument, the Driftless Area Education and Visitor Center in Lansing, Iowa, and the River Museum at LaCrosse.

We began to get a better sense of the story when we came across historical markers describing actions in the war appeared along the road in Wisconsin.(1) They were set up as a driving tour dedicated to the Black Hawk War, put together in the 1930s by a Wisconsin history buff named Dr. C.V. Porter, who was determined that the events of the war should not be forgotten. He put concrete markers at each stop. (They bear an uncomfortable, and not inappropriate, resemblance to tombstones.) In the 1990s, the Vernon County Historical Society restored the markers and added explanatory plaques. You can now drive a trail that follows Black Hawk’s doomed flight toward the Mississippi, aided by a pamphlet put out by the Vernon County Historical Society and the text on the markers.

Unfortunately, not all of the markers were on our path, and we did not read them in order. Which meant we did not get anything more from the markers than an unhappy sense that the story was an ugly one.

We finally learned the story from beginning to end at an unexpected stop on the road: the Genoa National Fish Hatchery.(2) Here’s the short version:

The conflict began in 1804, with the Treaty of St. Louis, when Sauk and Fox chiefs signed a treaty ceding a large portion of their land to the United States in exchange for $1000 a year and the right to continue using the land until the United States sold the land to settlers. There is some suggestion that William Henry Harrison, then governor of the Indiana territory,(3) resorted to trickery in the treaty negotiations. (In fact, President Jefferson wrote Harrison a letter suggesting ways that the Native American tribes could be pressured into selling their lands, including a establishing a monopoly on trading posts and then allowing Native Americans to get so deeply in debt that they had to sell their lands.) (4)

Black Hawk never accepted the treaty, claiming that the chief who signed for the Sauk did not have the authority to sell the land. He and his people traveled back to their settlement at Saukenuk, near what is now Rock Island, Illinois, each summer to grow corn and other crops. When they returned in 1828, they found that the government had sold off parcels of the Sauk territory to individual citizens. In fact, settlers were living in Black Hawk’s own long house.

In 1832, Black Hawk was determined to return his people to their home, encouraged by promises of help from the British, with whom he had sided in the war of 1812, and by visions of success from an influential medicine man named Wabokieshiek, known as the Winnebago Prophet. (You can see how this is going to work out, right?)

Relationships between the Sauk and settlers had been tense for several years. When Black Hawk crossed the Mississippi into Wisconsin from Iowa with a group of 1500 Sauk, roughly 1000 of them women , children and the elderly, skittish settlers sent word to General Edmund P Gaines. Commander of the Western Army, and Illinois Governor John Reynolds that Black Hawk had invaded.

By mid-April, Gaines and Reynolds, worried about the possibility of British support for the Sauk, had mobilized both the US Army and the Illinois state militia in pursuit of Black Hawk and his people.

Not surprisingly, the promised British support never arrived. In May, Black Hawk attempted to negotiate with a small group of Illinois militiamen under the command of Major Isaiah Stillman who were camped nearby. He sent three of his men with a white flag to the militia camp. The militiamen, who could not understand the three men’s language assumed the worst (despite the white flage) and fired on them, killing one of the truce bearers. When the Sauk retaliated, Stillman’s volunteers panicked and fled in the face of what they perceived to be a large body of warriors. The losses at what came to be known as the Battle of Stillman’s Run were few, but they were enough to end any hope of peace.

Soon Black Hawk’s main goal was to get his people safely back to Iowa. The local American authorities, fearful that Black Hawk and his band would trigger a general uprising among the local tribes, were determined not to let him get away.

Throughout June and early July, small bands of militia and Native Americans fought their way across northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin. (Not all of the Native Americans were part of Black Hawk’s band. Some other groups appear to have taken advantage of the situation to attack settlers, secure that Black Hawk’s people would take the blame.) Although the main Sauk band successfully eluded the pursuing militia, they had no time to rest or resupply.

On August 1, Black Hawk’s remaining forces, totally perhaps 500 men, women, and children, had reached the banks of the Mississippi near the town of Bad Ax.(5) Notified by members of the Winnebago tribe that the Sauk were at the river’s edge, the settlement at Prairie du Chien sent a steamboat upriver, carrying a detachment of US Infantry and a six-pound cannon, with orders to keep the Sauk from crossing the river. Black Hawk attempted to surrender to the steamboat captain, who fired on the unprepared Sauk

The following day, bands of militia pushed the Sauk toward the river, where the steamboat fired at those who tried to cross. The “battle” of Bad Axe lasted more than three hours. The few who made it across the Mississippi met a band of Sioux, who took advantage of the battle to settle old scores.

Black Hawk surrendered on August 27. He was held for a time at Fort Crawford, then sent east as the main attraction of a multi-city tour designed to impress his peers with the folly of standing up against the United States government. The United States used his rebellion as an excuse to demand further concessions from the Sauk and Fox chiefs, most of whom had not participated in Black Hawk’s doomed attempt to regain his homeland.

In my opinion, the fifteen weeks of the Black Hawk War of 1832 would be better best described as the Black Hawk Massacre. Not a story to be proud of.

(1) As I’ve mentioned in earlier posts, we love a good historical marker

(2) We came away from this trip very impressed with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Its information centers are right up there with those of the National Park Service.

(3) Best known as the president with the shortest tenure of office, dying after only 31 days in office. His death triggered a political crisis, which ultimately clarified how power is transferred when a president is unable to serve his full term. Not a small legacy. But I digress.

(4) Ironic, given Jefferson’s own problems with debt.

(5) Later renamed Genoa at the suggestion of a group of Italian immigrants who argued, probably with some justice, that the name Bad Ax attracted unsavory elements to the town.

* * *

Next up: A visit to the Black Hawk State Historical Site in Iowa, where we learned more about the Sauk and Meskiwaki nations in the period before the Black Hawk Wars.