Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 39

April 12, 2022

Aethelflaed, Saxons, Danes, and The Last Kingdom

Over the last few weeks, it seemed like almost everyone I knew was watching or had watched The Last Kingdom: a British television series based on Bernard Cornwell’s historical novels The Saxon Stories. It is set in Britain in the late eighth and early ninth centuries, when Alfred the Great* (and his adult children) defended their kingdoms against Norse invaders.

Several people mentioned that Aethelflaed, the Lady of Mercia whom I discussed in Women Warriors, enters the story in season two. They also mentioned that they were finding it hard to keep the underlying history of the Danes and the Saxons straight. Allow me to help, with an emphasis on Aethelflaed, whose role in the story is often not given a fair share of attention and is sometimes left out all together.

Beginning in 793, Viking raiders arrived in England each spring, as regularly as robins, and attacked the coasts and inland waterways of the British Isles. Over time, Viking raids evolved into permanent Danish settlements. By the end of the ninth century, the area known as the “Danelaw” covered a significant portion of England, from the north of Yorkshire to the Thames.

Alfred the Great (who reigned from 871-899) successfully defended the kingdom of Wessex against Viking attackers, but realized he could not drive them out of England entirely. In 886, he negotiated a treaty with the Danes, which left northern and eastern England under Danish rule and returned West Mercia and Kent to Anglo-Saxon control. I suspect you will not be surprised to learn that neither side honored the treaty, though it did slow down action across the border for a few years.

At the same time that he negotiated a treaty with the Danes, Alfred also built alliances with his Saxon neighbors. His most important ally was Aethelred, Lord of Mercia. In order to strengthen the alliance, Alfred arranged for his daughter and eldest child, Aethelflaed, to marry Aethelred.

We know little about Aethelflaed’s life until the first years of the tenth century, when Aethelred became ill. With no direct male heir waiting to inherit Aethelred’s crown, Aethelflaed became the effective ruler of Mercia during her husband’s illness. When he died in 911, she succeeded him without opposition—the only female ruler in the Anglo-Saxon period in England and one of only a handful of women in early medieval Europe who ruled in their own right rather than as a regent for an underaged son or brother. (The fact that Aethelfaed’s mother, Ealhswith, was a daughter of the royal house of Mercia may have played a role in the Mercians accepting her as their ruler.***) Aethelflaed was the Lady of the Mercians, just as Aethelred had been Lord of the Mercians before her. (Don’t let the title fool you. Aethelflaed was a ruling queen by any standard.)

In 917, the conflict between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings intensified. The West Saxon chronicles tell us that Aethelflaed’s younger brother, Edward the Elder, who had succeeded their father as the King of Wessex, occupied the Danish border town of Towcester, in modern Northamptonshire, shortly before Easter. In July, a Danish force counterattacked. By year’s end, the Viking armies of Northampton and East Anglia surrendered to Edward.

The West Saxon chronicles leave out the fact the Edward had more than a little help from his big sister. Aethelflaed, who was already experienced in warfare, led her own offensive against the Vikings. With Danish forces focused on her brother’s army, Aethelflaed took Derby in a savage battle; it was the first of the five great strongholds of the Danelaw to fall to Anglo-Saxon forces. The following year she led her troops against the important Danish fortress of Leicester, which surrendered without a fight. Danish Christians in York, apparently tired by being ruled by a non-Christian Viking from Dublin who had seized control of their region in 911, approached Aethelflaed (not King Edward) with a formal promise of allegiance. Before she was able to finalize the treaty, Aethelflaed died unexpectedly on June 12, 918, leaving Edward to win the final victory against the Danes and the place in the history books.

*I am sure you’ve heard of Alfred the Great even if you don’t know anything about him other than his name. I must admit, until a few years ago the only thing I knew about him was this story:

Taking shelter in the woods after being defeated once again by the Danes, the exhausted king stumbled into a herdsman’s hunt. The herdsman’s wife, who did not recognize him,** invited the hungry and tired man, whom she believed to be a simple soldier ,into her home. She put some oat cakes into the embers of the fire to bake and told him to keep an eye on them while she went out to get more firewood, or perhaps a bucket of water. As soon as she left the king fell asleep, no doubt soothed by the warmth of the fire and the smell of the cooking oat cakes. When the woman came back, she found burning cakes and a snoring soldier. Rightly incensed, the woman not only gave the soldier a tongue-lashing, she boxed his ears or perhaps beat him with her broom. (Different versions vary on the details.) Either way, King Alfred accepted his beating and apologized, without admitting who he was.

My guess is that this story is the medieval English equivalent of George Washington cutting down the cherry. As such it is a fine example of what I like to call “comic book history”: historical stories that are emotionally satisfying but factually untrue.

Just to bring this back to the main topic of this post: I have no idea whether this episode occurs in The Last Kingdom. Anyone?

**And how would she? She probably had not even seen a coin with his portrait. Even if one of the “Alfred coins” had passed through her hands, the “portrait” would not have been useful for identification.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

*** Even if you know something about Alfred the Great, you probably haven’t heard of Ealthswith unless you’re a medievalist because we tend to leave mothers out of royal family trees. When you add the missing mothers–and grandmothers, and aunts and sisters, etc— back in, you often find unexpected connections. And sometimes even answers.

April 8, 2022

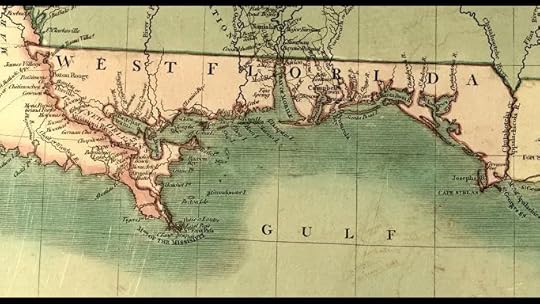

The Free and Independent Republic of West Florida

And speaking of short-lived, mostly forgotten nations, as I believe we were, allow me to go back into my notes from our road trip in 2015, and dig up a story that never got the blog post it deserved. *

The Free and Independent Republic of West Florida made the Free State of Fiume look like it had a long and venerable history.

West Florida, which at its height included much of what is now Florida, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana, became a diplomatic football between Britain, France, Spain, and eventually the United States at the end of the eighteen and beginning of the nineteenth century. Possession of the region was passed from France, to Spain, to Britain. In 1783 it was returned to Spain in the treaty that ended the American Revolution. Spain subsequently ceded Louisiana to Napoleon in 1800. ***

When the United States bought the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803, Spain insisted that the ceded territory did not include the area known as West Florida, which extended from the Perdido River in Alabama across Missisipi and Louisiana to the Mississippi River. Rather than confronting Spain over the issue, first President Jefferson and then president Madison let the matter slide.

Meanwhile, British and American colonists in West Florida became increasingly disgruntled with the Spanish colonial government. On September 23, 1810, a small group of settlers “attacked” Fort San Carlos in Baton Rouge by walking through the open gate and firing a single volley of shots at the Spanish soldiers who held it. They then raised a new flag—a single star on a blue ground—and declared the foundation of the Free and Independent Republic of West Florida. They quickly established a capital in St. Francisville, in modern Louisiana, adopted a constitution, and established a supreme court and a two-house legislature.

It was clear from the beginning that the founders of the new republic were hoping to become part of the United States. And seventy-four days later, on December 10, that is exactly what happened. The United States claimed possession by a simple proclamation. The Lone Star flag came down—though it would rise again when American colonists in Texas revolted against Mexican rule.

* I n 2015 we set out to spend three weeks on the Great River Road,** with the plan that we would drive south from Memphis and then head back north as far as we could go. We spent two days in Memphis, three days in New Orleans, and then drove north along the Mississippi without a schedule, stopping at anything that caught our imaginations. We didn’t last the full three weeks. And we only got as far north as Vicksburg because we made lots of stops–between us we are interested in just about everything. Since then we’ve been following the river in shorter stints, ten days to two weeks at a time. You can follow our adventures, and others, in the category “Road Trip Through History.”

** Which, like the Silk Road, is not a single road but a conglomeration of 3,000 miles of local and state roads that roughly follow the course of the Mississippi.

***If you are interested in knowing more about the colony of West Florida, as opposed to the republic, I strongly recommend reading Kathleen Duval’s Independence Lost.

April 5, 2022

The Free State of Fiume

And speaking of oddities in the Versailles Peace Treaty, as I believe we were, allow me to introduce you to the Free State of Fiume.

I stumbled across the story while I was working my way through old articles in the Chicago Tribune, trying to untangle a messy problem of chronology, when I ran across this opening line in an article dated August 23, 1919: “Fiume, child of trouble since History began…” Despite myself, I read on.*

The headline, in case any one is interested, read “Grazioli May Be Italy’s Goat for Fiume Riot: Witnesses Agree Italians Began Massacre of the French.” It was the 1919 equivalent of click bait. While there were indeed riots, and French troops were indeed massacred, the heart of the story was the conflicting claims of the relatively new country of Italy (1861) and the even newer country of Yugoslavia (December 1, 1918) over the Adriatic port of Fiume (aka Rijeka). Up and down the Dalmatian coast from Cattaro to Trieste, the general opinion was that the longer the old men in black coats at Versailles delayed making a decision the more likely it was that there would be another riot in the streets of Fiume.

I had to know more. And down the rabbit hole I went.

The Great Powers came up with a solution that probably satisfied no one: the establishment of the port as an independent buffer state between the competing claimants. Woodrow Wilson suggested that it could serve as the home for the League of Nations, making it an independent buffer state for the whole world. All eleven square miles of it.

The Free State of Fiume existed from November 12, 1920 through the end of 1923. Instead of being an emblem of peace it was a tiny version of the Wild West. The first election was immediately contested. Governments came and went, sometimes in a matter of a few days. The Nationalists, Fascists, the smallest Communist party in the world, and the Italian poet Gabriele d’Annunzio, who had occupied the city for fifteen months beginning in September 1919,** all seized power and were overthrown in turn. In January 1924, the Kingdom of Italy and Yugoslavia signed the Treaty of Rome, in which they agreed that Fiume would become part of Italy and its suburb of Sušak, became part of Yugoslavia.

(If you are reading this in an email and you want to see the newsclip, click through to your browser.)

After World War II, Fiume, now called Rijecka, became part of Yugoslavia. It is now part of Croatia.

*I am trying to sort out which Tribune correspondents were in Berlin between 1919 and 1926. And the job would go much faster if I limit myself to reading the by-lines, datelines, and occasionally relevant headlines—which gave me all the material I needed. But I keep getting sucked into stories. And really, wouldn’t you want to know more if you read an opening like that one? (The complete sentence, for anyone who’s curious, read: “Fiume, child of trouble since History began, is as quiet now as a Dearborn street soft drink dispensary.”)

**If you do the math, you’ll find that he held the city-state for almost a month after its creation, until he was expelled by the Italian Army in what became known as the “Bloody Christmas” campaign.

April 1, 2022

Why was Chief Mkwawa’s skull an issue in the Treaty of Versailles?

First, let me make it clear that this story is NOT an April Fool’s joke. Even if I enjoyed prank stories as a way to celebrate foolishness on April 1st—and I don’t*—over the last few years we have seen so many unbelievable true stories that it is sometimes are to tell the real articles from satirical stories in The Onion.

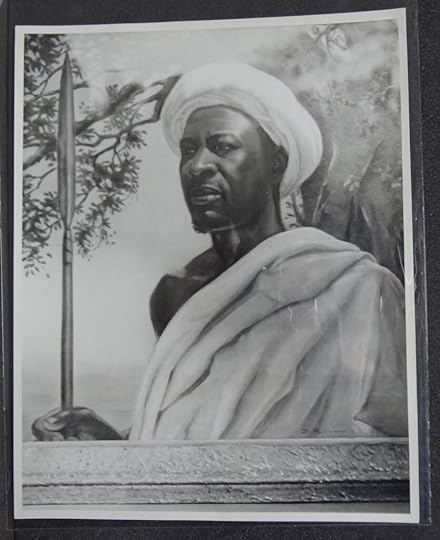

That said, the story of Chief Mkwawana’s skull has the “ Wait! What??” quality common to so many of the fake stories that clutter the internet on April 1 each year. But it also has a dark side. In fact, despite the “what?” factor, it is mostlydark side. This is a story about colonialism, resistance, and political symbolism. (Feel free to imagine exclamation marks liberally sprinkled throughout.)

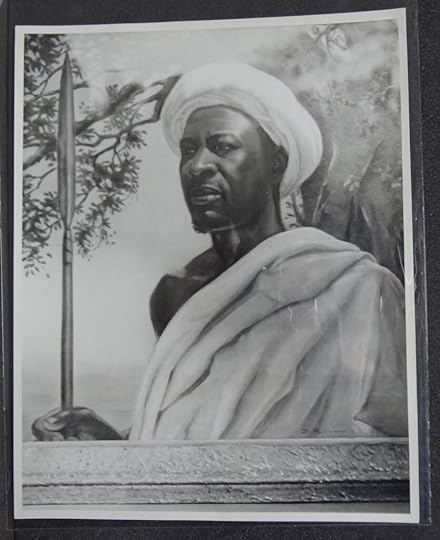

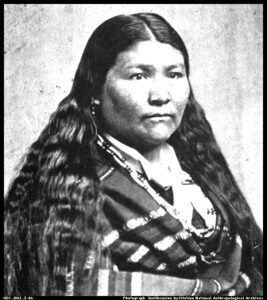

A portrait of Chief Mkwawa, painted by Mrs B. Kingdon, wife of a British District Commissioner-who I suspect never saw him.

An odd clause appears in the Treaty of Versailles, sandwiched in between the War Guilt Clause and the Financial Clauses. Article 246 stated: “Within six months from the coming into force of the present Treaty … Germany will hand over to His Britannic Majesty’s Government the skull of the Sultan Mkwawa, which was removed from the Protectorate of German East Africa and taken to Germany.”

Mtwa Mkwava Mkwavinyika Mahinya Yilimwiganga Mkali Kuvago Kuvadala Tage Matenengo Manwiwage Seguniwagula Gumganga was the chief of the important Wahehe people in the newly founded colony of German East Africa (now part of Tanzania). He led the HeHe in a determined resistance against the invaders for seven years.

In 1898, the Germans placed a bounty on his head—an ironic phrase given how things turned out. In the ensuing manhunt, a party lead by Sergeant Major Merkl had closed in on Mkwawa. Hearing a shot, they hurried toward the camp and found two dead bodies, one of which was identified as Mkwawa, who had previously declared that he would commit suicided rather than surrender to the Germans. (Exactly who did the identifying in unclear in the references I’ve read.) Merkl ordered one of the African soldiers in his party to cut off Mkwawa’s head so he could take it back to camp. (And presumably claim the bounty.) His captain took charge of the head and, in Merkl’s account, ”had it dried”—a disturbing war trophy by any standard. (Though apparently not unique, as we shall see in a moment.)

Perhaps not surprisingly, Mkwawa became a heroic symbol of the struggle against the colonial powers.

On November 14, 1918, only a few days after the Armistice that ended World War I was signed, Sir Horace Byatt, administer of the former German East Africa, suggested to the Colonial OPffice that Britain should try to recover Mkwawa’s skull from Berlin, where it was said to be exhibited in a museum, as a good will gesture to the HeHe tribe, which had been helpful to the British during the war.

The skull was included in a schedule of art and artifacts which had the Germans had seized that and were required to be returned as terms of the peace agreement.

Unfortunately, no one knew where it was.

On May 6, 1920, the German Foreign Ministry said that they couldn’t find the skull and in fact found no indications that it had been brought to Germany. A year later, Winston Churchill, the newly appointed Secretary of State for the colonies, decided to let the matter drop.

It didn’t stay dropped. Enquiries were made about the skull in the 1930s, the 1940s, and again in 1951. Finally, in 1953, the German Foreign Ministry announced that the skull might be part of a large collection in a museum in Bremen. Faced with the question of how to identify the correct skull, someone suggested comparing them to the cephalic index of Mkwawa’s grandson, Chief Adam Sapi, which was an apparently unusual 71%.**

The British governor of the former German East Africa (then called Tanganyika, for anyone who likes to read with a map) visited the museum, which had a large cabinet full of skulls. After identifying those which had been taken from German East Africa, they were measured. Of the two skulls with the appropriate cephalic index, one of them had a bullet hole that had entered at the back of the head and come out through the front. (I will remind you the Mkwawa had reportedly committed suicide.) A German police surgeon confirmed the hole was consistent with a type of rifle used by German troops in East Africa.

Having determined, with some enormous logical leaps, that this was Mkwawa’s skull, it was shipped from Berlin to Tanganyika via diplomatic pouch and presented to Chief Adama Sapi in a formal ceremony on June 19, 1954.

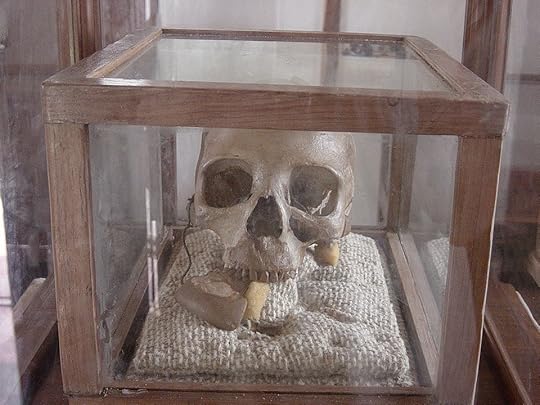

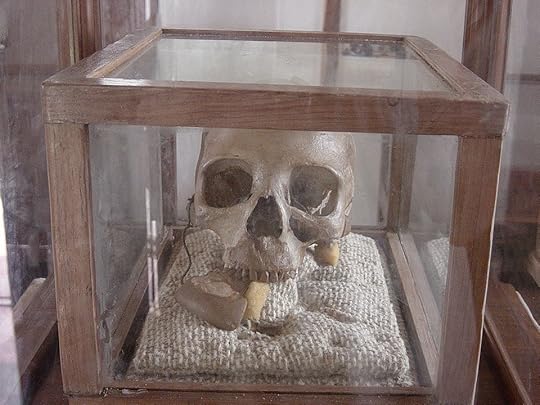

Today the head is displayed on a plinth in a glass box in a museum in Tanzania.

Skull of Chief Mkwawa on display in the Mkwawa Memorial Museum, Kalenga, Iringa.

*Personally, I’m a big believer in celebrating foolery—but I don’t think most pranks are funny.

** I’ll save you the trouble of googling. The cephalic index is the measured width of the head divided by the length of the head multiplied by 100 and reported as a percentage. It is used to categorize the shape of skulls—and has strong racist/colonial roots as part of early anthropologists’ attempts to “scientifically” categorize different peoples.

Why was Chief Mkwawa’s skull an issue the Treaty of Versailles?

First, let me make it clear that this story is NOT an April Fool’s joke. Even if I enjoyed prank stories as a way to celebrate foolishness on April 1st—and I don’t*—over the last few years we have seen so many unbelievable true stories that it is sometimes are to tell the real articles from satirical stories in The Onion.

That said, the story of Chief Mkwawana’s skull has the “ Wait! What??” quality common to so many of the fake stories that clutter the internet on April 1 each year. But it also has a dark side. In fact, despite the “what?” factor, it is mostlydark side. This is a story about colonialism, resistance, and political symbolism. (Feel free to imagine exclamation marks liberally sprinkled throughout.)

A portrait of Chief Mkwawa, painted by Mrs B. Kingdon, wife of a British District Commissioner-who I suspect never saw him.

An odd clause appears in the Treaty of Versailles, sandwiched in between the War Guilt Clause and the Financial Clauses. Article 246 stated: “Within six months from the coming into force of the present Treaty … Germany will hand over to His Britannic Majesty’s Government the skull of the Sultan Mkwawa, which was removed from the Protectorate of German East Africa and taken to Germany.”

Mtwa Mkwava Mkwavinyika Mahinya Yilimwiganga Mkali Kuvago Kuvadala Tage Matenengo Manwiwage Seguniwagula Gumganga was the chief of the important Wahehe people in the newly founded colony of German East Africa (now part of Tanzania). He led the HeHe in a determined resistance against the invaders for seven years.

In 1898, the Germans placed a bounty on his head—an ironic phrase given how things turned out. In the ensuing manhunt, a party lead by Sergeant Major Merkl had closed in on Mkwawa. Hearing a shot, they hurried toward the camp and found two dead bodies, one of which was identified as Mkwawa, who had previously declared that he would commit suicided rather than surrender to the Germans. (Exactly who did the identifying in unclear in the references I’ve read.) Merkl ordered one of the African soldiers in his party to cut off Mkwawa’s head so he could take it back to camp. (And presumably claim the bounty.) His captain took charge of the head and, in Merkl’s account, ”had it dried”—a disturbing war trophy by any standard. (Though apparently not unique, as we shall see in a moment.)

Perhaps not surprisingly, Mkwawa became a heroic symbol of the struggle against the colonial powers.

On November 14, 1918, only a few days after the Armistice that ended World War I was signed, Sir Horace Byatt, administer of the former German East Africa, suggested to the Colonial OPffice that Britain should try to recover Mkwawa’s skull from Berlin, where it was said to be exhibited in a museum, as a good will gesture to the HeHe tribe, which had been helpful to the British during the war.

The skull was included in a schedule of art and artifacts which had the Germans had seized that and were required to be returned as terms of the peace agreement.

Unfortunately, no one knew where it was.

On May 6, 1920, the German Foreign Ministry said that they couldn’t find the skull and in fact found no indications that it had been brought to Germany. A year later, Winston Churchill, the newly appointed Secretary of State for the colonies, decided to let the matter drop.

It didn’t stay dropped. Enquiries were made about the skull in the 1930s, the 1940s, and again in 1951. Finally, in 1953, the German Foreign Ministry announced that the skull might be part of a large collection in a museum in Bremen. Faced with the question of how to identify the correct skull, someone suggested comparing them to the cephalic index of Mkwawa’s grandson, Chief Adam Sapi, which was an apparently unusual 71%.**

The British governor of the former German East Africa (then called Tanganyika, for anyone who likes to read with a map) visited the museum, which had a large cabinet full of skulls. After identifying those which had been taken from German East Africa, they were measured. Of the two skulls with the appropriate cephalic index, one of them had a bullet hole that had entered at the back of the head and come out through the front. (I will remind you the Mkwawa had reportedly committed suicide.) A German police surgeon confirmed the hole was consistent with a type of rifle used by German troops in East Africa.

Having determined, with some enormous logical leaps, that this was Mkwawa’s skull, it was shipped from Berlin to Tanganyika via diplomatic pouch and presented to Chief Adama Sapi in a formal ceremony on June 19, 1954.

Today the head is displayed on a plinth in a glass box in a museum in Tanzania.

Skull of Chief Mkwawa on display in the Mkwawa Memorial Museum, Kalenga, Iringa.

*Personally, I’m a big believer in celebrating foolery—but I don’t think most pranks are funny.

** I’ll save you the trouble of googling. The cephalic index is the measured width of the head divided by the length of the head multiplied by 100 and reported as a percentage. It is used to categorize the shape of skulls—and has strong racist/colonial roots as part of early anthropologists’ attempts to “scientifically” categorize different peoples.

March 31, 2022

Women’s History–Not Just a Month

We’re coming to the end of Women’s History Month. Here on the Margins it’s been a month of fascinating interviews with people doing exciting things in the field.*

The fact is, I could interview someone about this work every day of the week and not run out of people to talk to.** People are doing wonderful work researching and writing about women who are forgotten, erased, or shoved to the side in the historical record: novelists and journalists and artists and musicians and labor organizers and scientists and activists and business owners and general shin-kickers. Historians are looking at the networks between women, the institutions they formed, and the ways in which they navigated cultural restrictions. Public historians are adding women to museum exhibitions and historical site interpretations. At this point, I can’t keep up with the new and exciting books that are coming out. Not to mention the podcasts. (Are there women’s history tiktoks? Do I dare go down that rabbit hole?)

It would be nice to reach the point where we don’t need Women’s History Month, or Black History Month, or any of the other history months and heritage months that mark our calendars. A point at which history as we learn it would include people who were not at the center of power as a matter of course. I don’t have an answer about how we do that, but I don’t think it happens by relegating women to a sidebar, a chapter, or a special section on women in history taught once a year during Women’s History Month.

Rant over. For the moment.

* I take no credit for this. I invite people. I ask them questions. And then I get out of the way.

**This is not going to happen. I would run out of energy long before I ran out of people to interview. And my book would never get finished. I do, however, already have three names on the list for next year.

March 30, 2022

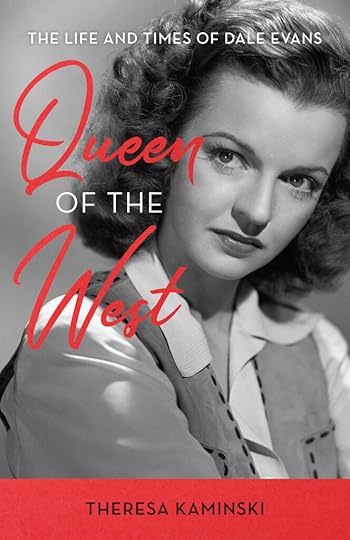

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer With Theresa Kaminski

Theresa Kaminski and I are co-administrators (and occasionally, co-conspirators) for a Facebook reading called Non-Fiction Fans, where readers and writers of narrative nonfiction meet up to talk about great non-fiction and how it gets written. She is also a wonderful writer of women’s history and a generous member of the on-line literary and historical community.

Theresa, who earned her PhD in history from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, specializes in writing about scrappy women in American history. She is the author, most recently, of Dr. Mary Walker’s Civil War: One Woman’s Journey to the Medal of Honor and the Fight for Women’s Rights. Theresa also wrote a trilogy of nonfiction history books on American women in the Philippine Islands during World War II. Her biography of Dale Evans, Queen of the West: The Life and Times of Dale Evans, is due out from Lyons Press in April 2022.* After more than twenty-five years as a university history professor, Theresa is now retired from teaching (but not from writing), and lives with her husband in central Wisconsin at a place known affectionately as Southfork.

Take it away, Theresa!

Writing about historical figures like Dale Evans requires living with them over a period of years. What was it like to have Evans as your constant companion? (Not to mention Roy Rogers.)

I’ve been living with this project for over ten years, and I really liked having Dale Evans as a constant companion. (Roy, although personable and charming, wasn’t so constant. See #3 below.) There were so many facets to her public and private lives that it was never dull. Still, ten years is a long time for a nonfiction project.

I began the book when I was still working fulltime as a professor of history, so my day job always came first. Still, I completed most of the research, both with secondary sources on Hollywood, television, radio, big bands, and twentieth century American women’s history, and with the primary sources I could track down, mostly the autobiographical books Dale Evans wrote.

Two unanticipated delays stretched out the project. One was the brand-new, biggest, and first of its kind, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans collection, acquired by the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles. I wasn’t comfortable about turning in a manuscript to any press until I’d researched that collection. But the problem was that the museum’s archives was closed (and remains so) to researchers because of a move to a new facility. The only way to access the collection was through an archives research fellowship, which I received in 2019. I’m so glad I stuck to my conviction to wait because the contents of that collection helped shape my vision of Dale Evans.

The other delay: I got a literary agent. And she wanted me to write a book (which would be my third) about American women in the Philippine Islands during World War II. So I set aside Dale Evans for a few years to write what became Angels of the Underground.

I always knew I would return to Dale Evans and, after yet another book, Dr. Mary Walker’s Civil War, I did. Dale’s personality and her accomplishments proved too much to ignore. And it was mostly because of her friendly, outgoing personality that I decided to refer to her by her first name in the biography. What to call their subject is something every biographer wrestles with, but for a variety of reasons, it’s more complicated with a woman. Sometimes that’s because of birth names and married names, which was something I had to consider. But with Dale Evans, an already complicated situation became more so because she opted to use a stage name.

Dale Evans was the name she chose for her singing career. She was born Frances Octavia Smith, and as both Frances and Dale, she had husbands. So how to refer to her throughout the book? I settled on most often using her first name, Frances in the first couple of chapters, before she took a new name. After that stage name was adopted, she became Dale. The two things that most influenced these choices were my perception of Dale Evans’s personality and the mood I wanted to convey with the biography. I think it worked.

Your previous books have dealt with women doing extraordinary things in times of war. With Dale Evans you’ve moved to popular culture. Did you approach your subject differently?

My research and writing methods don’t change much project to project. I felt a bit of initial relief that I wouldn’t have to deal with the trauma and drama of war this time around. While I was mapping out the Dale Evans project, I kept hearing “Down by the Riverside” play through my head, especially the line, “I ain’t gonna study war no more.”

There is a lot of joy in Dale’s story, and a lot of excitement with breaking into show business and becoming a star. It was fun to get immersed in twentieth-century popular culture. I loved reading up on early radio and television, nightclub and big band singers, and, of course, Hollywood. Plus there was all that great Western fashion. I really envied Dale’s boots.

But I also wrote about events in Dale’s life that were traumatic, and I don’t mean just the professional setbacks. She dealt with so much sorrow in her private life.

Are there special challenges in writing about a woman whose biography closely tied to that of a famous man? Do you feel like Roy Rogers overshadowed Dale Evans?

While they were married, I think he often did. Roy Rogers was massively popular in the 1940s and 1950s, both with children and adults. Thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, of people showed up at his personal appearances. Dale Evans had a solid fan base, too, but few performers could compete with Roy in the popularity department.

So one of my biggest challenges as Dale’s biographer was to not let Roy’s story take over hers. I read a few dual biographies of Roy and Dale that seemed lopsided, like Dale was just along for the ride (pardon the pun) and that her only importance–even her fame–came from her marriage to Roy. My book shows how Dale Evans made a name for herself as a singer and actor well before she met Roy, though of course their professional and personal partnership significantly enhanced her celebrity.

Some Roy Rogers fans may think I went too far in Queen of the West, turning him into a supporting character. But I think the story has just enough Roy. I must admit, Roy was a fascinating person, and I sometimes got caught up in reading too many accounts of his activities. But it was really time for Dale to have her story told.

* My copy arrived on March 25, so it may be in stores by the time you read this.

Question for Pamela: When I read nonfiction, it’s almost always women’s history. I know that’s an interest of yours, too, so what work of women’s history have you read (or perhaps watched or listened to) lately that you loved?

I’m going to circle back to the place we began this series of interviews on March 1: Shelley Puhak’s The Dark Queens: The Bloody Rivalry that Forged the Medieval World blew me away, from the opening when she tells the reader how she came to the story through the epilogue, where she explores why the story was—not exactly lost but definitely under-told and misrepresented. (The epilogue’s title, “Backlash,” says it all.) An exciting story, with lots of twists, based on impeccable research, told with beautiful language and a certain amount of attitude. In other words, just my cup of lapsang souchang.

***

Want to know more about Theresa Kaminksi and her work?

Check out her website: https://theresakaminski.com/

Follow her on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheresaKaminskiHistorian

Follow her on Twitter: @KaminskiTheresa

Follow her on Instagram: @hers_torian

* * *

Come back tomorrow for one last Women’s History Month post.

March 29, 2022

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle

I am thrilled to have, sister-professors Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle, the hosts of the , back as my guests. I listen to a lot of podcasts, but What’sHerName is one of a handful that I make sure I listen to on the day they go live. What’sHerName tells the stories of fascinating women you’ve never heard of (but should have). The show is an engaging blend of story-telling, historical banter between the hosts, and interviews with experts. It is consistently smart, funny and thought-provoking. (And I thought that before they asked me to record an or with them.)

Katie and Olivia bring impeccable credentials to the project:

Katie Nelson has a PhD in History from the University of Warwick and teaches courses in history, travel, and the meaning of life at Weber State University. She loves exploring life’s big questions and bringing students to Europe every year on study abroad courses.

Olivia Meikle teaches Gender and Women’s Studies at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. She has an MA in English Literature and Women’s and Gender Studies from the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Now they have a new project coming out: The Book of Sisters is a non-fiction book for kids (or eternally curious adults) about sisters who made a mark on history, coming out on April 4th. I can hardly wait for my copies to reach the bookstore

Take it away, Katie and Olivia!

* * *

There is a long tradition of collective biographies of notable women, that are written to provide female role models for girls. Do you see The Book of Sisters as part of that tradition?

Katie: I’m not sure if our editors originally conceived of the book in that vein, but I wanted to put a very different twist on it. I had the idea of writing a history of the world, in sisters. I was awed and a bit intimidated by the thought: could we authentically cover all the main episodes of world history with a new set of glasses on, so to speak? I knew it would be a big challenge. Happily for me, our amazing editors were on board too!

And there are certainly plenty of women in the book who shouldn’t be anyone’s role models! Rather than being inspiring, they are downright terrifying. Some sets of sisters destroyed each other and everyone around them…and it’s all part of the wider human story. I am so glad we were able to present the whole variety of human experience. I think it’s important NOT to present historical characters as idealized heroes to model our lives on. Who could ever live up to a perfect fantasy? We’re all flawed humans, stumbling toward enlightenment.

Olivia: Yeah, I’m pretty proud that this book is so much more than just what can sometimes (not always!) turn into a fairly reductive and/or dismissive “big book of ladies” – and instead we’re taking this often-complicated relationship and using it as a throughline through human history, looking at these characters and events – some well-known and some very unknown – from a unique and very specific angle that (we hope) yields equally unusual and fascinating results! (Just to be clear: There are lots of GOOD examples of those type of books. I own tons of Books of Ladies that I love dearly!)

Was it difficult to find historical sisters for the book?

Katie: Happily, a decade of teaching world history at university helped me out here. Still, as I was mapping out the historical roadmap of the book, there were some “chapters” of world history that struck me as particularly masculine. Genghis Khan’s Mongolian Empire, for example – where would I find sisters in this (immensely important, primary source-starved) episode of world history? But wouldn’t you know it – just a little bit of digging beneath the surface led me to Jack Weatherford’s book, The Secret History of the Mongol Queens, and there it was: Genghis Khan’s daughters built and sustained the whole operation. Without those four sisters, there would have been no Mongolian Empire.

This confirmed for me that the lack of women in our historical narratives isn’t the fault of today’s historians. The scholarly research and the books are out there, now: we just need to help those stories make the leap into popular culture, placing these women as main characters in our collective historical narratives. Hopefully, with a book like this, we can help make that leap a reality.

Olivia: Yeah, I confess I was a bit nervous if we’d be able to do it, but this kind of thing kept happening – whenever there were particular “holes” we needed to fill in the narrative or in the map, after a bit of determined digging we’d uncover another incredible story just begging to be told! And thank goodness for supportive spouses. Our wonderful men got almost as invested in the project as we did – I can think of at least three ‘sets’ of sisters in the book that my husband Matthew found before I did!

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

Olivia: I recently finished 18 Tiny Deaths,about the completely fascinating Frances Glessner Lee, the middle aged Chicago “socialite” responsible for almost single-handedly establishing modern forensic medicine in the US in the early 20th century, and it was such a wild and unexpected story I could hardly put it down! The relentless and passionate commitment this woman showed toward what she saw as the pursuit of real ‘justice for all’ was inspiring and totally astonishing. And I know Katie just basically devoured Kim Todd’s Chrysalis, on 17th century naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian, who was doing groundbreaking field research on entomology and botany almost a century and a half before Darwin.

Katie: I also want to plug the podcast The Exploress as one of my favorite works of women’s history “in any format.” Kate Armstrong’s research and attention to detail is impeccable, and the script is full of so many laugh-out-loud witty remarks. I love it!

And for our question for you – We want to know your thoughts on the long tradition of collective biographies designed to provide female role models for girls?

I read those books as a kid, when I could get my hands on them. (There weren’t as many of them then as there are now.) And I loved those books. They gave me models that said it was okay to be tough/mouthy/opinionated/different.

But ultimately I think we need something more than role models. We need to show young girls, young boys, and grown-ass people of all genders that “women’s history” is simply history. Because we were there, y’all. We were there.

***

Want to know more about Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle and the amazing work they do?

Listen to the podcast:

Follow them on Twitter:

Follow them on Facebook:

Follow them on Instagram:

* * *

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Theresa Kaminski, author of a new biography of Dale Evans, the Queen of the West.

March 28, 2022

Talking About Women’s History: Four Questions and an Answer with Michael Cooper

Here’s the official bio: Dr. Michael Cooper, the Margarett Root Brown Chair in Fine Arts, has had research interests in 19th-century music, source studies, historiography and political history, specializing in Mendelssohn, Schumann, Berlioz, and Richard Strauss. He has also spent the last three decades in research of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds, and is a leading editor of the music of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds.

Here’s the passion behind it: “I’m a musician. I’m a teacher. I’m a scholar. I have a passion for social justice. I believe that the most important thing we can do — for ourselves, our understanding of who we are, our history, our future — is to learn music and understand how it serves as a lens into the world that produces it and a lens into who we are. Music is the key to understanding ourselves in all the diverse beauty and complexity of the human condition. And it is the key to making our world a better world.

The most important thing, though? That is to learn the music that we do not already know — the musical voices that others are not already telling us to listen to, the voices and works that have been erased from our collective history. “

My guess is that’s a mission statement that all the Marginalia can get behind.

What path led you to Florence Price and Margaret Bonds? And why do you think it is important to tell their stories today?

This is a story both professional and deeply personal for me. I was in my mid-twenties when I first heard Price’s Songs to the Dark Virgin and Bonds’s Three Dream Portraits, and I was thunderstruck – I remember nothing else about the program, but the experience of those two works was like nothing known to me before. I immediately tried to find more music by these two obviously marvelous composers – but could only get to a tiny handful of other works, even though both Bonds and Price were reportedly quite prolific. A quarter-century later, the situation was the same: a very small body of works by Price and Bonds (4-10 pieces each) kept being recycled. What were the other hundreds of pieces, and what were they like?

I wanted to know, needed to know: it was like a burning question that had been simmering unanswered for a quarter-century. By then I had dealt with most of the contractual obligations that had kept me from addressing it for so long. I had also learned how to understand musical manuscripts and conduct archival research, and seen that the music suppressed by our world’s obsession with genuflecting before canonical “Great Men” was usually far worthier of mainstreaming than canonical works are. So when pianist Lara Downes (whose 2016 recording of Price’s First Fantasie nègre contributed much to the momentum of the current Price renaissance) encouraged me to follow through on the notes I had been taking over the years about those “missing” (unknown = marginalized and suppressed) compositions, I decided to go for it. I plunged headlong into the thousands of pages of manuscripts of both Price and Bonds – and I was stunned by what I found there, by its consistent beauty, by its eloquence and power, ceaseless originality. I started inputting the content of those musical autographs into my computer (editing the works), and so got to know the music from the inside out, putting one note at a time onto the pages, one bar at a time. It was so beautiful and amazing, each work so different from every other even though all clearly came from the same springs, that I couldn’t stop. By today, because of that work, the voices of Margaret Bonds and Florence Price have gifted me a huge musical universe of dazzling beauty, intensity, and originality. My musical universe has been enriched and transformed by their legacies. That long-unanswered question has been addressed, its fire supplanted by light.

I think we need to tell the stories of Bonds, Price, and countless other composers who have been marginalized because of their sex and/or their race partly because of the wonders that they left to our world, legacies without which the world is poorer. Beyond that, it’s impossible to understand any history if we hear only one group of its voices (by which I mean male voices, most of them White and most of these European). That’s like looking at a few pixels and pretending you’ve seen the picture. Most important, though, is the general principle that the marginalization and suppression of women and persons of color is, to put it plainly, wrong. We have to choose whether we accept that wrong and go on about business as usual, or call it out for what it is (wrong) and resist it with every fiber of our being. That path of resistance – the path of listening to voices silenced and suppressed – is the only conscionable way forward, the only way to make it possible for future generations to know a better, richer, more just world than we do.

Are there special challenges to researching women of color, who in some ways have been doubly erased from history?

“Doubly erased” is an apt term – and it’s an important one for me, a White male, to keep in mind as I approach the powerfully expressive art of two Black American women, one of whom (Price) was nearly ten years dead before I was born. As we all know, the tendency of White historiography and male historiography is to portray history and its art through White male eyes, thus perpetuating the very same White and male gaze that marginalized women and people of color to begin with. That approach to history not only marginalizes women and people of color; it also inevitably – and worse – misses the point of what they saw in their art, and wanted others to see there.

While it’s true that I feel obligated (having watched the musical world stand idly by for decades while the very music by Price and Bonds that it’s interested sits in the libraries and archives, unheard, unstudied, untaught) to do my best to help get that music and other aspects of those composers’ lives out into the public, I have to respect the challenge for me to, in some senses, suppress my own perspective, White and male as it is. Because it seems to be the historian’s nature to speak with authority, the challenge that researching women of color poses for me, and for all of us, is to remain humble rather than asserting authority, to listen more than we talk.

What can we learn when we use music as a historical source?

Because of music’s pervasive presence in cultures worldwide throughout history and its universally acknowledged position among the arts that are natural expressions of the mathematical order of the cosmos (Boethius’s quadrivium) as well as created through human imagination, music has an extraordinary capacity for serving as a lens into the ideas, issues, ambitions, and questions of the worlds of its historical composers and performers and their audiences. For the same reasons it’s also been an agent of change and social discourse. What’s more, historical music has an amazing ability to kindle emotional responses, to stimulate the intellects and imaginations, of historical observers. The chants of Hildegard of Bingen, the violin works of J.S. Bach, the symphonies of Louise Farrenc, the fantasies nègres of Florence Price – all these can speak to modern performers and listeners with an immediacy fully equal to that with which they addressed themselves to their contemporaries. They can connect us directly to those long-dead composers, and thus make their worlds more approachable than they might be otherwise. Music thus has a remarkable ability to connect us to a past that might otherwise be hopelessly remote; to articulate the voices of composers that are otherwise now forever silent; to share the ideas, questions, and inspirations of their creative imaginations with us with an immediacy that makes it perhaps every bit as powerful as a source of inspiration and agent of change today as it was in its own time.

Do you think Women’s History Month is important and why?

Women’s history month is incredibly important as a thing in itself, but even more so as a first step toward an eventual future where women’s history is no longer regarded as something that could possibly be celebrated in just thirty days. That future must come. For now, Women’s History Month acknowledges that 50%+ of the population and their myriad creations and contributions to history deserve to be celebrated not just as counterparts to men (as is usually the case) and not just as tokens in a male-dominated and resolutely male-chauvinist world, but on their own, and (more importantly) on their own terms.

We all know that the current thirty-one-day span will see more public and scholarly celebration of women’s history than the next 334 days will. That needs to change, has to change. Women’s history month is one small step in the right direction, and it’s important to me as an opportunity to drink deeply of the wealth of ideas and inspirations created by women throughout history and get a sustaining dose of those legacies – legacies that will be shamelessly marginalized and tokenized until the next Women’s history month. I look forward to March, 2023.

(Reminder: If you are reading this in your email, you probably need to click over to your browser to view, and more importantly listen to, these video clips.

A question for Pamela: Correcting the erasure of women’s voices by restoring their presence in historical narratives is essential work, but wholesale erasure is only one of the techniques by which women have been marginalized and women’s contributions diminished. Another is historians’ tendency, when writing about women, to go out of their way to emphasize historical women’s attachments to men who are already recognized as important: commentators on Florence Price attach her to George Chadwick more than they need to and ought to; commentators on Margaret Bonds overly rely on her relationship with Langston Hughes; historians discussing Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel or Clara Wieck Schumann seem unable to discuss them as composers and musicians in their own right without making them indebted to Felix Mendelssohn or Robert Schumann in ways that, for these historians, do not seem to be reciprocated by Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann. The list goes on and on – and its ultimate result is that the women who are discussed emerge as exponents of, or pendants to, “Great Men,” while male-centered narratives treat women as footnotes or incidental. The imbalance is a historiographic artifice that’s insidious in its undermining of the progress made by restoring women’s presence in historical narratives from which they’ve traditionally been erased.

The question, then: what do you think about this problem? And, more to the point, do you have suggestions about how to most effectively address it?

First, I think it is a very real issue. Every year in this series, I ask about the special challenges of writing about someone who is best known as the “wife of” someone or who is otherwise overshadowed in the literature by a man in their lives. And every year, I get interesting answers to the question.

I think one of those answers gets to the heart of how to address it. Music historian Angela Mace Christian said that the biggest problem she has in writing about women like Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel is her own thought process:

I find myself consistently needing to stop and think carefully about if what I’m thinking is based on a long-held assumption about the relationship of a female artist to her brother, or whether what I am thinking is an objective analysis of evidence. I find that this issue crops up frequently when analyzing the music. It is incredibly tempting to compare the music of Felix and Fanny, because it truly does share a sort of genetic fingerprint. I find that many of us also fall into the habit of comparing composers to everyone who came before them; it’s hard not to, especially when a composer like Beethoven was very much alive and working when Felix and Fanny were teenagers. It can even be completely appropriate for some works, such as Fanny’s “Easter” sonata. But what if we didn’t compare them? What if we dug into the music of Fanny, just like we dig into the music of Bach or Beethoven or Brahms? What could we find that we’ve missed? What happens if we truly level the playing field, take gender and kinship out of the equation, and approach the work of art head on, regardless of its composer?* That’s incredibly difficult for me, since I do primarily write on the social context around Fanny, with a special interest in kinship, but it might be the best way to overcome those inherent biases in our minds and the historical record.

In short, we need to constantly wrestle with the opinions we hold so deeply that we don’t even know they are opinions, whether we are talking about race, gender, ethnicity, or religion. (And there are probably other things that ought to be on that list that I am not thinking of right now.) Sometimes it feels overwhelming, and exhausting. But I believe it’s important.

(FYI: Social psychologist Dolly Chugh has a book coming out in October that will be dealing with some of these issues head-on : A More Just Future: Psychological Tools for Reckoning with Our Past and Driving Social Change. I am eager to read it. In the meantime, I strongly recommend her newsletter, Dear Good People for evidience based and delightful discussion of these topics. You can subscribe here: https://www.dollychugh.com/newsletter)

***

Want to know more about Michael Cooper and his work?

Check out his website: https://cooperm55.wixsite.com/jmc3

Read his blog: https://cooperm55.wixsite.com/jmc3/blog

***

Come back tomorrow for three (or six, depending on how you count) questions and an answer with Olivia Meikle and Katie Nelson, hosts of the , talking about their newest project The Book of Sisters.

March 25, 2022

Three “Lady Coders”: a Guest Post by Jack French

I love it when readers of History in the Margins reach out to share something they think will catch my interest, or a suggestion for a blog post, or a gentle correction. Long time reader Jack French occasionally offers to tell me, and you, a story. It is always interesting, and I am always pleased to welcome him back.

Take it away, Jack!

* * *

While women have excelled in the art of code breaking, they have seldom received the recognition they deserved. First because they were women in what historically was a man’s world, and secondly because most of their impressive accomplishments were classified by the government agency for whom they worked.

Three of the most skilled and talented women code breakers in American history were Agnes Meyer Driscoll, Elizebeth Smith Friedman , and Genevieve Grotjan Feinstein. But The Code Book, (Anchor Books, 1999) an extensive history of cryptography by Simon Singh, while detailing the work of hundreds of men, does not even mention one female code breaker. The massive 1136 page The Code Breakers (Macmillan Company, 1967) by David Kahn also describes the work of hundreds of men. Kahn relates some of the successes of Friedman, has three sentences about Driscoll (one under her maiden name) and totally ignores Feinstein. It would be up to Liza Mundy and her brilliant book, Code Girls, (Hachette, 2017) to give proper credit to the entire trio of these lady code breakers, as well as the great multitude of unsung female analysts in the Army and Navy who contributed to cracking the German and Japanese codes and ciphers in WW II.

Agnes Meyer was born in Illinois in 1889 and got her degree in mathematics and physics from Ohio State. She also studied foreign language and was fluent in four of them. After a brief career as a school teacher, she enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1918 and was assigned to their Code and Signal Section where she excelled. She married Michael Driscoll, a DC lawyer in 1924, by which time she had become one of the Navy’s top codes and cipher experts. The government awarded her $ 15,000 for a cipher machine that she and William Greshem invented. Her small Navy team broke the Japanese code in 1926 and also broke the one the Japanese replaced it with in 1930. By 1939 she had solved Japan’s entire fleet code. In 1940 she was transferred to the group working on the solution to the German Enigma coding machine. Dubbed “the First Lady of Navy Cryptography” she last worked for the National Security Agency (NSA) retiring in 1959 at the age of 70. Driscoll died in September 1971, age 82, and was buried in the National Cemetery in Arlington. In 2000 she was inducted into NSA’s Hall of Honor.

Elizebeth Smith Friedman was born the youngest of nine children in 1892 in Indiana. She graduated in 1915 from Hillsdale College with a major in English and minor in foreign languages. She briefly taught school before being hired at Riverbank Laboratory, a private entity that worked with government agencies to break codes and ciphers. There she met and married William Friedman; the two of them would spend the rest of their careers breaking codes and solving ciphers for the federal government. Although they both worked for the War Department, she left in 1923 to become the head of the code breaking section of the Department of Treasury, Bureau of Prohibition and Customs. Her job was to crack the codes of bootleggers and international smugglers, which she did brilliantly. Her success resulted in her transfer to the U.S. Coast Guard, where she continued to successfully attack the codes used by violators of the Volstead Act, solving over 12,000 coded messages in three years. Her court testimony in criminal trials resulted in convictions of over thirty smuggling ring leaders. In WW II, she testified against “The Doll Lady” who was convicted of being a Japanese spy. Friedman led the team that broke the German code used for their spy network in South America, although J. Edgar Hoover claimed the credit for the FBI. She died in October 1980 at the age of 88; after cremation, her ashes were scattered over her husband’s grave in the National Cemetery. Friedman is the only one of the talented trio to receive some acclaim recently; two biographies about her, plus a children’s book, have been released in the past five years and her accomplishments were lauded in a PBS television special in January 2021.

Genevieve Grotjan Feinstein is the least known of the trio of remarkable lady code breakers, but this does not mean her accomplishments were less impressive. She was born in 1913 in Buffalo, NY and graduated from the University of Buffalo, summa cum laude, with a degree in mathematics in 1938. The following year she was hired by William Friedman in the Army Signal Intelligence Service, which concentrated on breaking the codes of Germany. From then until her retirement from the government in 1947, she would be the linchpin of her unit in breaking whatever codes which they were assigned. In 1940 she made a discovery that enabled her team to break the Japanese “Purple Code”, which was the protection of their diplomatic corps message traffic. This also opened the door to German military plans, which were relayed to the Japanese diplomatic corps. Later, working on Russian codes, she devised a process for recognizing the reuse of its code keys, thereby permitting the decryption of KGB messages. She had married chemist Hyman Feinstein in 1943 and she retired from federal service and became a mathematics professor at George Mason University in Fairfax, VA. This illustrious code breaker died at the age of 93 in August 2006.

* * *

Jack French is a former Navy officer and retired FBI Agent in Virginia. He is a vintage radio historian and the author of two published books on the subject. Jack is a guest lecturer whose topics include: Civil War Heroines, History of Toys & Games, and the Golden Age of Radio.

You ca learn more at his website: www.jackfrenchlectures.com

* * *

Come back on Monday for four questions and an answer with music professor Michael Cooper who is involved in reviving the work of composers Florence Price and Margaret Bonds