E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 9

April 16, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Margaret McNamara: A Poem In Your Pocket

When I was six, my parents moved our family from suburban New Jersey to Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, England. It wasn’t Little Whingeing, but it was close. I was enrolled in a convent school where we ate in silence, learned to write with fountain pens, and were provided an abacus to help us with arithmetic. And this wasn’t so long ago.

Schwartz & Wade, January 2015.

Being a child, I was able to adapt quickly to the near-Dickensian environment. I liked my new school. We did needlework and had a garden tended by the nuns. And the best thing of all: we had elocution lessons.

Elocution was taught by Miss Joy Glanville. She smelled of cigarettes and coffee, but she had gorgeous diction. Her job was to help us enunciate, to make us unafraid to speak in front of groups, and to open us up to the wonders of the English language. This she did by teaching us poetry.

We did not analyze poems. We spoke them. We felt them. And we memorized them. We recited our learned poems singly, in pairs, in groups. I especially loved our choral readings. These were not mere unison chants: they were carefully directed, orchestrated, modulated performances, where the ebb and swell of multiple voices gave the poem an amplified voice, so different than the unassuming way it appeared on paper.

Margaret McNamara, age 7.

I still have poems in the pocket of my brain that I learned from Miss Glanville. Speeches from Shakespeare; easy, baby rhymes; lyrical verses that appealed to young girls. I committed many poems to heart as I progressed out of Miss Glanville’s elocution lessons, into high school and college. I had a torrid love affair in my adolescent imagination with John Keats, and another with John Donne (very different experiences!). To this day, in the dentist’s chair, I recite “Ode to a Nightingale” in my head to drown out the dentist’s drill.

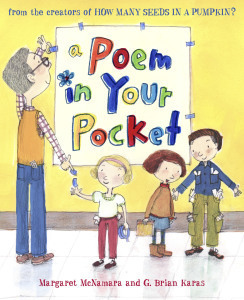

My book for National Poetry Month, A POEM IN YOUR POCKET, brilliantly illustrated by G. Brian Karas, is about a girl who’s not like me: she’s a perfectionist; I’m not. But like me, she learns to keeps a poem in the pocket of her mind, which she can call forth any time.

There is nothing more empowering than confidence, and Miss Glanville’s insistence on memorizing poetry gave me the confidence to use language with assurance, to speak it aloud, and to rely on it when I need it most. If teachers have even a moment of the day when they’re not being made to train kids for testing, I would hope they might encourage their students memorize a poem, however short, however goofy. There’s a certain sense of triumph that comes from memorization. Hearing a poem recited, and reciting it back, is a shared experience that is empowering to all.

A POEM IN YOUR POCKET is dedicated to Miss Glanville. I owe her a lot. I hope the book provides a moment to think about poetry and the world of words this April. Learn a poem by heart and it will be with you forever.

Margaret McNamara. Photo by Tish Webster.)

MARGARET MCNAMARA is the penname for Brenda Bowen, a literary agent and writer who lives in Manhattan. She is the author of three picture books about Mr. Tiffin’s classroom: HOW MANY SEEDS IN A PUMPKIN? (winner of the Christopher Award), THE APPLE ORCHARD RIDDLE (American Farm Bureau Book of the Year), and, most recently, A POEM IN YOUR POCKET, which SLJ called “a great book to share during National Poetry Month.” McNamara is also the author of the Fairy Bell Sisters series and Robin Hill School books, and, under her real name, will make her debut as a novelist for adults with ENCHANTED AUGUST, releasing in June, 2015.

April 15, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Julie Marie Wade: It Could Have Happened So Many Ways

It Could Have Happened So Many Ways. But it happened this way.

I was twenty, not quite twenty-one. I was about to be a senior in college. My best friend was about to get married and move with her husband to California. I was about to realize I didn’t love men the same way that I loved women.

The fact was, we were all on the cusp of something, and some of us liked the word cusp—how one syllable contained a hard and soft together, forming a perfect equilibrium.

Bywater Books, Reprint Edition, November 2014.

But an actual cusp was more dubious. We weren’t sure how we felt about the feeling.

I was just home from my first and only study abroad. Seeing more of the world had the unintended effect of making me feel smaller, less than before I left.

*

Before London, there was a plan. My father printed many pages of information concerning PhD in Psychology programs. He left these pages in a tidy binder on my desk.

Their arrangement this way made them seem even less desirable, made me feel even smaller.

Sheaf is a good word. I like it almost as well as cusp. It is soft on both sides with a little rise in the middle. Its slant-rhyme is yeast, which seems significant in this context.

But my father had not left me a sheaf of applications. He had left me a stack. The pages were no longer warm, since they had been printed many months before.

On my desk, I also noticed a lean manila envelope, my lone piece of mail after four months away. Both my parents said EN-ve-lope, like envy or environment. I said ON-ve-lope, like placing a bet on something.

*

“Do you know anything about this?” I ask my mother—this book called Willow Springs. The cover sports a mysterious creature wearing a Shriner’s hat and holding, either a thick blade of grass or a green magician’s wand.

I decide it’s a blade because I prefer the word blade to the word wand. This preference is part of my ongoing romance with the long A, but I don’t discuss this kind of thing with my parents.

“I told you I don’t want you ordering from The Amazon,” she replies. By this, she means a local company of newly national reach, not a particular member of a tribe of warlike women. My mother herself is something of an Amazon, but shorter, I think, than Amazons typically are.

“I didn’t order it,” I say. “It just came.”

“Well, then, maybe it’s from a secret admirer.” Her thick, mascaraed lashes flutter. This is meant to be ironic, since my mother is rapidly losing hope I’ll ever have one of these.

*

Willow Springs, Issue 44, June 1999.

What is immediately apparent is that I would rather read Willow Springs than work on my psychology applications. In fact, I would rather read Willow Springs than do almost anything else. While I’ve been taught out of anthologies for most of my life, this one is different. I don’t even recognize it as an anthology at first because 1. No author or editor names appear on the front cover 2. There is no subtitle instructing me as to the time periods, countries, and literary movements represented by this anthology and 3. The poems and stories the book contains are not prefaced by long, dry, fact-laden forewords. The poems and stories are allowed, at last, to stand alone.

And then this: I am so engrossed in reading that I drop the book (Butter fingers, my mother would say, a metaphor as sensuous as it is accurate), and when I pick it up, I notice a section called Contributors’ Notes: So-and-So lives or So-and-So works or So-and-So is the recipient of X awards. All the verbs are present tense. I may have gasped, or I may have added the gasp to my memory in retrospect. Regardless, this is what shocks me most: These So-and-Sos, these writers of poems and stories whose work has been collected here, are not only smart and interesting and accomplished people. They’re…wait for it…ALIVE!

*

Fifteen years in the future (prolepsis), it shocks me most to remember how shocked I was by the fact that living writers of poems and stories were publishing in places like Willow Springs and then going on about their collective business of not being dead. It shocks me second-most to realize that Willow Springs was not at that time an example of a literary journal to me, a one among many. Rather, it was the only literary journal to me—a sui generis compendium of contemporary writing that appeared in my mailbox without precedent or explanation. I didn’t know the “44” meant there had been 43 previous editions or that, as I’m writing this Whatever-You’d-Call-It today, in the spring of 2015, Willow Springs has just released their 75th issue. The journal is celebrating “Forty Years of Poetry and Prose.”

This is the thing about cusps: We so often can’t see that we’re on one until we’ve fallen off.

A Midsummer Night’s Press, March 2014.

I read Issue 44 of Willow Springs thoroughly, in order, cover to cover, the way I have never read (will never read) a literary journal again. There are so many of them, and there is so little time by comparison. I skip around now. I look for names of writers I recognize, titles that catch my eye. I always flip to the poetry section first. But back then (analepsis), I didn’t know there were more of these to come. I didn’t recognize any writer names. I couldn’t name any of my preferences yet. So of course I couldn’t have imagined that in just two years, I’d be one of the two poetry editors for another literary journal based in Washington State—the Bellingham Review. That I’d be a graduate student in creative writing instead of psychology. That the other poetry editor would be my partner in more than poems, the woman I would marry someday.

A few days later, a letter arrived from Eastern Washington University. We hope you’ve received your complimentary copy of Willow Springs by now. Just think: as a graduate student in our Master of Fine Arts program, you could contribute to the literary legacy that has kept Willow Springs going strong for a quarter-century now…

I’m paraphrasing. I didn’t keep the letter, but I did make some notes. Eastern Washington University? Master of Fine Arts program? This entire period of my life seems to have been surrounded by question marks. I went to the library and got on The Internet. I may have even got on The Amazon. I was feeling about as risky and adventurous as I had ever felt.

This is another thing about cusps: if at all possible, it’s better to leap than to fall.

*

It could have happened so many ways—my not becoming a psychologist, or a secretly admired heterosexual.

The moral of this story is not that LITERARY JOURNALS SAVE LIVES, though if you’re affiliated with a literary journal, feel free to borrow this slogan, print it on t-shirts and wrist bands, or wave it like a flag.

But I do believe that LITERARY JOURNALS CHANGE LIVES, or at least that this particular journal arriving at this particular time changed mine—and indisputably for the better. I opened the book and found a hallway instead of a page. Every title was a door. Every door I opened took me into a room where I wanted to stay, closer to a person I wanted to be. Where once I had been ajar, I was now agape. Everything spoke to me like an oracle, both prophetic and summative.

Surely Jennifer Oakes must have been speaking for me when she wrote the poem, “The Listener.” Her speaker says, “I begin each day blank as an uncut key.” How else to describe my own experience as I entered this book and as I moved through the world? I was a key in need of cutting.

Her speaker describes “eight thousand/ voices all asking in different ways/ whether they must eat alone at the table/ of their hearts forever.” This was a question I had been asking without words for most of my life, but in Oakes’ poem, the words were extended to me at last like an offering. What a gift to be able to name what is felt at last!

They were also a version of an ars poetica, a term I would later learn, describing the panoply (surely eight thousand constitutes a panoply) of other writers and artists who made literature and art in response to this essential human question of love and loneliness.

*

I was going to have to tell my parents that I wasn’t going to graduate school in psychology. In their language, this was going to sound like a declaration of personal and professional failure. Before too long, I was going to have to tell my parents that I wasn’t going to marry the man I began dating my senior year. In their language, this was going to sound like a suicide note.

Sarabande Books, November 2011.

Jennifer Oakes named precisely the pained anticipation I felt, tottering there on the cusp of self-disclosure, in the final couplet of her poem: “It would take fire or breaking glass to tell them/ the poppy, the apple, the vein.”

In the kitchen, my mother was chopping vegetables. My father was reading the paper. I held Willow Springs in my hand like the panoply it was, meaning both “a striking array or arrangement” and “that which covers and protects.”

Then, I faltered on the cusp. Without precedent or explanation, I said, “Words mean more to me than anything else.”

They looked up. They looked at each other and then at me. I tried again. “Listen,” I said, and for a few moments, we were all present on the same page, walking together down the same hall, standing outside the same door.

In other words, it happened this way: My parents fell silent, and I read them a poem.

*

The Listener

I begin each day blank as an uncut key,

but in the shower I start hearing neighbors

twelve blocks over

washing the body of their mother.

It comes through the pipes, comes tight

as the lasso of a stutter, dragging

its word from the tongue’s falling house.

I hear the advice of psychics

when I pick up my telephone, of eight thousand

voices all asking in different ways

whether they must eat alone at the table

of their hearts forever.

Of mannequins ashamed of their severed wrists,

the shot star gone unseen, calling out

to the dust of old planets that it is coming,

and trees unbinding storms from their branches.

But hardest are the seeds of the bloodfruit.

Their words are so red they enter

only once and desperately at knifepoint.

They believe they are alone in their cardinal

tongue, sanguine and praying.

It would take fire or breaking glass to tell them

The poppy, the apple, and the vein.

—Jennifer Oakes, reprinted from Willow Springs Issue 44, June 1999

Julie Marie Wade.

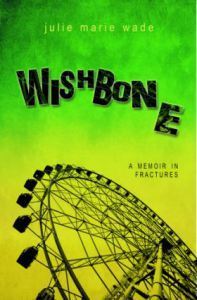

Born in Seattle in 1979, Julie Marie Wade completed a Master of Arts in English at Western Washington University in 2003, a Master of Fine Arts in Poetry at the University of Pittsburgh in 2006, and a PhD in Interdisciplinary Humanities at the University of Louisville in 2012. She is the author of WISHBONE: A Memoir in Fractures (Colgate University Press, 2010; Bywater Books, 2014), winner of the Lambda Literary Award in Lesbian Memoir; WITHOUT: Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2010), selected for the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Series; SMALL FIRES; Essays (Sarabande Books, 2011), selected for the Linda Bruckheimer Series in Kentucky Literature; POSTAGE DUE: Poems & Prose Poems (White Pine Press, 2013), winner of the Marie Alexander Poetry Series; TREMOLO: An Essay (Bloom Books, 2013), winner of the Bloom Nonfiction Chapbook Prize; WHEN I WAS STRAIGHT: Poems (A Midsummer Night’s Press, 2014), selected for the American Library Association’s Over the Rainbow List; and the forthcoming collections, CATECHISM: A Love Story (Noctuary Press, 2016) and SIX: Poems (Red Hen Press, 2016), winner of the AROHO/To the Lighthouse Prize. A regular book reviewer for The Rumpus and Lambda Literary Review, Wade teaches in the creative writing program at Florida International University. She is married to Angie Griffin and lives in Dania Beach.

April 14, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Nickole Brown: Ostranenie & Awareness: Defamiliarizing the Apple

There’s nothing more important to me as a poet—and as a human being, really—than awareness. Paying attention is, I think, my primary responsibility as a writer. If I don’t notice the quiet tickings within my own self, I can’t fully appreciate the secrets and mysteries carried within my own body and memory, and perhaps more importantly, my work as a writer is work as a noticer, an observer of others and the life outside my own.

BOA Editions, April 2015.

Below is an exercise I use often in the classroom to try to teach students to pay attention deeply. I think it’s the most essential and basic thing a beginning writer must embrace; it’s more important than any lesson on language or syntax or tone. You won’t need much to do this exercise, really. Just some good, slow time with a group of students.

I’ve seen many poems come out of this exercise and have included one here by Seth Pennington, one of my students who graduated from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock a few years ago and is now an Editor at Sibling Rivalry Press. This exercise was printed in the second volume of a sharp and useful anthology of creative writing exercises edited by Scott Wiggerman and David Meishchen called WINGBEATS II, published by Dos Gatos Press in 2014.

Ostranenie & Awareness: Defamiliarizing the Apple

Dos Gatos Press, June 2014.

Rationale for the exercise:

How do you teach a writer to use imagery? How do you hound them out of cliché? How do you convince that the body—with its imperfect clash of all the senses—is the way into language? The trick, to me, has not been to shame writers away from their emotions and abstractions (since those are mostly likely the things that brought them to the page in the first place). Instead, I teach awareness. By awareness, I mean attention as a form of devotion; as a raw, muscular kind of seeking; as an unflinching dedication to scrubbing away one’s preconceived notions of a thing in order to see it for what it really is; as a discipline—the core discipline—of writing.

Awareness—as it’s taught to visual artists in the drawing studio or to practitioners of meditation who attempt to sit silently for hours on end—isn’t a passive reception of information. No, it is focus, a striving, something that most beginners will fail at time and again. But its worth? Invaluable. Those who achieve true awareness are changed by it. This exercise is the most succinct way I know to demonstrate this transformative power and to have students begin that practice.

Required materials:

Apples. One for each student. Preferably a variety of apples, so that each has a slightly different shade and size. (It’s a thoughtful gesture to wash them beforehand, but don’t remove the grocer’s sticker.)

Some napkins or paper towels.

Sample poems about apples. I like to share a variety of poems that talk about apples in completely different ways, including Grace Schulman’s “Apples,” Tom Hansen’s “Fallen Apples,” Dorianne Laux’s “A Short History of the Apple,” and Donald Hall’s “White Apples.”

Step-by-step procedures:

Start with a discussion of defamiliarization. A simple definition is “the technique of forcing the audience to see common things in an unfamiliar or strange way, in order to enhance perception of the familiar.” Ask: if we are all telling the same stories of love and sex and death, how can we write something new? How can we sidestep the spiritual nausea of cliché? The answer doesn’t lie in writing about something completely different (if that’s possible) or in shocking your readers awake, but rather in writing about those things you know intimately well, so much so that perhaps you don’t even notice them yourself anymore. (If you meet the class regularly, it’s a good idea to incorporate as homework the night before Charles Baxter’s wonderful essay, “On Defamiliarization,” from BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE; he makes this argument so eloquently.)

As a quick exercise, ask the students to take out their notebooks and draw a picture of a tree. Most likely, each participant will draw something that looks like a cloud on a stick. Does this really look like a tree? If there’s a window, have them go to it. What are those odd, ticking sticks in the breeze? And how is it that each student has drawn a tree without first asking what kind? Does a Palm look remotely like a Ginkgo? Or how about a River Birch or an Oak? Crepe Myrtle, Holly, White Pine—the list goes on. And how is it that we’ve simplified the world, that we’ve wired ourselves for simplicity and efficiency so much so that we’ve washed out the strangeness, the true complexity of the world?

If there’s time, another good thing would be a quick dip into linguistics, talking about the difference between the signifier (the word itself, spelled out in four letters, “T-R-E-E”) and the signified (the thing itself, whatever particular tree it is, which is far more complex than the signifier can even come close to addressing). This, of course, points to the essential lack and laziness in language itself, and most importantly, how hard one must work to try to carve reality out on the page.

An easy segue way from this conversation is to talk about the apple. What fruit is more commonplace and thus more overlooked? Humans have enjoyed apples since about 6500 B.C., and no other fruit is rife with more clichés. From Eve’s temptation to a doctor’s prescription, we’ve been inundated with the apple ever since we put a shiny, red apple on the desk of our grade school teacher. In turn, she taught us, flash-card icon of an apple in hand: “‘A.’ ‘A’ is for apple.” There’s likely no food that we take more for granted than the lowly apple, and thus, no fruit more difficult to write about in a fresh way.

At this time, tell them this is exactly what they’re going to do: write about an apple (one particular apple, that is) for the remainder of their time. Then take out the bag of apples and tell them each to choose one carefully, as they’ll be with it for quite a while.

Depending on how much time you have, it’s often helpful to take ten minutes with each of the senses. I usually start with sight, stressing on the importance of seeing something new, as if you’ve never seen it before in all your life. Attention to color is important (most will assume, quite wrongly, that apples are uniformly red), as is shape (which is never, as assumed, really symmetrical). I then move on to touch, asking them to ascertain the exact texture form of their apple. Does it feel like anything else? What about the temperature? Or the ridges one can feel if fingering around the horizontal circumference of an apple? Similarly, move on to taste, smell, and sound. Have them reach for metaphors whenever possible, especially if the comparison is completely unexpected, making the description new and unexpected.

Have the class share their perceptions, without necessarily reading from the page. At this point, it’s not about performance or about the actual production of a written piece, but about observation. Awareness in itself should be enough. Ask: Did anyone notice something completely strange about your apple? How can we see it new? Can you make it strange? These observations are what later can go into a poem about an apple, or conversely, about something completely different that employs apple imagery. It’s all about filling up one’s warehouse of imagery: one simple observation made today, during a concentrated time with something so commonplace, could be the exact line you need to use in a poem, perhaps years down the road.

To wrap up the class, I like to share poems written about apples so that the students can consider different ways into the subject matter. As homework, I often like to assign a poem that came out of this exercise. If possible, I try to give the group a few weeks to find their own lines.

Variations and/or adaptations of the procedures:

This exercise can be done again and again, with a hundred different variations on things we take for granted. A trip outside to actually examine trees is fantastic when possible, but you could use most anything we think we “see” but no longer see at all. Stawberries are a good, less expensive option, but I’ve also used lychees and seashells and even grapes.

Red Hen Press, September 2007.

Comments/tips/suggestions for success:

When prompting the students to write, tell them not to write a poem. Most of the time, reaching for something profound and writerly will get in the way of true observation. The writing during class should be something more akin to sketching, taking down details and discovering metaphors, but not necessarily imposing any sort of cohesion and meaning yet.

When writing through the senses, remind them of kinesthetic (tactile) learning and encourage them to apply force here and there, puncturing and rolling and tossing up their apples here and there. You can even have them smash them to the ground. Descriptions can often feel as if they’re behind museum glass without movement, and encouraging play like this can do a lot to move this exercise along.

It’s often best to have all students bite into their apples at one time, perhaps on the count of three. Even better if you can turn off the lights and have them take that first bite in the dark!

Sample poem:

Bloodswoll

You claim you are numb. Still

I watch you finger your

stomach and press the twist

of navel.

I want to ask:

Do you miss your mother?

How she held you

kinked in her arms? Or

when she let you go—

was that too much?

Your skin isn’t different from mine.

You tell me you are softer

but know it’s only your young age.

I point to each scar, and you

recite their stories with the same fervor

as Bradbury and his tigers. I have

a favorite—in your roundness

I found a globe’s mountain

range raised from a paring knife.

It matches my mother’s on her right

hand; a bottle scar, a memory:

a mad sister, her heroin

flushed. Neck bloodswoll, crying out,

thin-boned.

There are days when I bite into you,

and you only taste of pink and water.

Like I’m tasting the last of all

you have to offer.

I leave my mark in you

with my whole mouth, and you rest.

This is how

you want to be used.

—by Seth Pennington

Nickole Brown.

Nickole Brown grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and Deerfield Beach, Florida. Her books include FANNY SAYS, a collection of poems forthcoming from BOA Editions in 2015; her debut, SISTER, a novel-in-poems published by Red Hen Press in 2007; and an anthology, AIR FARE, that she co-edited with Judith Taylor. She graduated from The Vermont College of Fine Arts, studied literature at Oxford University as an English Speaking Union Scholar, and was the editorial assistant for the late Hunter S. Thompson. She has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Kentucky Foundation for Women, and the Kentucky Arts Council. She worked at the independent, literary press, Sarabande Books, for ten years, and she was the National Publicity Consultant for Arktoi Books and the Palm Beach Poetry Festival. She has taught creative writing at the University of Louisville, Bellarmine University, and at the low-residency MFA Program in Creative Writing at Murray State. Currently, she is the Editor for the Marie Alexander Series in Prose Poetry at White Pine Press and is on faculty every summer at the Sewanee Young Writers’ Conference. She is an Assistant Professor at University of Arkansas at Little Rock and lives with her wife, poet Jessica Jacobs.

April 13, 2015

National Poetry Month: Lynn Melnick & Brett Fletcher Lauer, Editors of PLEASE EXCUSE THIS POEM, Interview Each Other

Brett Fletcher Lauer: The book is finally here. I think we started working on the book and sending it to agents and editors over three years ago, which may as well be forever. I’m uncertain if I had a beard or could even grow one then. I think my voice has cracked. We’ve had the fortune to talk a little bit about the impetus behind creating the anthology in both The Volta and The Poetry Foundation and so I won’t make you recount buying poetry books at the Goodwill as a wayward youth, but I am wondering how you are feeling now that the book is out in the world?

Viking Books for Young Readers, March 2015.

Lynn Melnick: Ha, thank you, and I can’t remember if you had a beard. It was 2011, I think, July or August, when we first began talking about it. I am feeling amazed and unbelievably grateful that the book is out in the world. I want as many kids as possible to read it! I guess I’m anxious to see if kids actually do read it! I’ve gotten some really nice emails from some of our poets about how much they would have loved this book as teenagers, but I’d love to hear from actual teenagers – just to make sure we did our job right! You used to write actual snail mail letters to poets as teen, and you got some responses, as I recall. What was your favorite?

BFL: I know exactly what you mean. I don’t run in many teenage circles these days, or snapchats, or the newest swipe-bot-friend-list-like-mechanism, so there isn’t immediate feedback on how we did our job. But, I’ll allow myself the briefest possible moment of pride, and say I think we did okay. And yes! As a teenager I wrote letters to poets and musicians. I sent the standard fan mail to bands like Sonic Youth, The Flaming Lips, and The Blonde Redheads. I wrote to Edward Hirsch about an article of his about anti-Semitism in T. S. Eliot’s work and I wrote a letter to Rita Dove about how politics could or does fit into poetry.

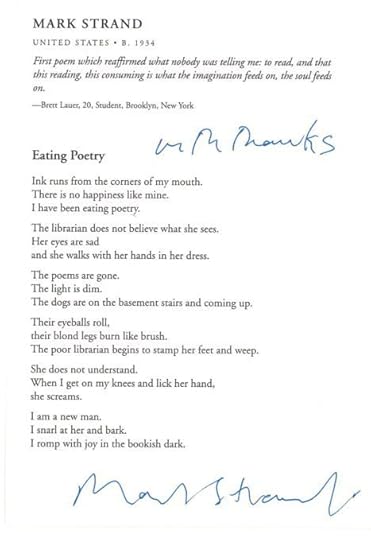

I can remember this now, I think, only because all of these people wrote back and I still have their letters. Especially in the cases with the poets of whom I was inquiring about something specific and not just gushing, though I’m sure I did that too, they wrote back serious and thoughtful letters. I’m sure the first time I was exposed to the phrase and concept “the personal is political” was through Rita Dove’s mention of it in her letter. Those were definitely very formative interactions for me as a poet, their generosity in replying, taking my questions seriously, encouraging a stranger to continue writing poems and thinking critically about poetics truly did give me a sense that poems were important and did matter outside of my teenage journal. I also wrote in to Robert Pinksy’s Favorite Poem Project, though I was 20 at the time so my teenager years had just past. They printed my little blurb about Mark Strand’s poem “Eating Poetry” in one of the editions, and, a decade later at an event in New York City, I was able to have him sign the page, which I now have framed in my apartment.

I know you just wrote about Diana Wakoski for the Los Angeles Review of Books, were there other poets or mentors that were important to you in your so-called “formative” years?

Los Angeles Review of Books

LM: Diane Wakoski was certainly a huge influence on me and I’ve in recent years also begun admitting to myself how huge the Beat poets were to the formation of my ear as a poet. I kind of wanted to reject that influence because it is such a male-dominated crowd and the work is so often problematic in that way but the rhythms they often used and the kind of stream-of-consciousness employed by many of them is not the furthest thing from my sensibility. And some of those poems are downright great, like Ginsberg’s “Kaddish,” for instance.

When I was an older teenager I discovered the Sisterhood Bookstore (may she rest in peace) in Los Angeles and that’s where I discovered Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, H.D., Sylvia Plath and so many others who would form another huge part of my sensibility as a poet, and person. I have been fortunate to study with some amazing poets but no mentor had a bigger impact on my life than the late playwright Phil Bosakowski who said to me “you are a writer” at a crucial stage where I needed someone to say that to me in order to begin to believe it. He is a large part of why I wanted to make Please Excuse This Poem (and as you know I thank him in the acknowledgements!). Did you have any mentors in your life who influenced a kind of decisive turning point for you in your life as a writer?

BFL: I certainly had a host of people who supported my interest in poetry and treated it as something which was of value, and even something someone could study in college and pursue, and those people include my father, my oldest brother, a teacher, Ms. Martinez, who I had an independent study with during lunch hour.

I don’t ever remember anyone telling me that maybe it would be more prudent to minor in poetry and major in business, or even more prudent to major in education. And that seems like a radical thing to me, maybe both radical in their oversight given my college debt, but really radical to be presented with the possibility that I could follow my creative interests, to be given that blessing, so to speak. I guess that brings me back to the anthology—in which hopefully the poems and poets in this collection are the expression of just that, of that possibility. Does that sound too wishy-washy? Too sentimental? God, I’d hate to come off that way.

LM: No! Well, I don’t think we can be too sentimental about how it is we discovered the thing we love. Nor about how amazing it is to see the varying voices and visions all coming from different starts and going different places. That sounds corny, yes, and actually kind of vague. But, getting back to the anthology, as you say, what I’m trying to say is that the most extraordinary thing about working on this has been to gather all the different voices into one book, and to get to know, through the bios and Q & A’s in the back, the stories of how the poets came to poetry and why they love poetry and who they are reading etc. I mean, like, if this book was a dinner party, I would be so thrilled for the invite. And the generosity of our poets has been pretty extraordinary too. In fact, so many poets—both who are in the book and who are not in the book—have been really excited to take the anthology to their high school or college classes and teach the poems. It’s a dream come true. I mean, can you believe we got to do this? Now what should we do? I don’t want to stop working with you, it’s too much fun!

BFL: Same here! Although, I think this might be a good moment to end our time together, or rather just this interview.

LM: Thanks for still talking to me after all this time working together…

Lynn Melnick.

Lynn Melnick is co-editor, with Brett Fletcher Lauer, of PLEASE EXCUSE THIS POEM: 100 New Poets for the Next Generation (Viking, 2015) and author of the poetry collection IF I SHOULD SAY I HAVE HOPE (YesYes Books, 2012). She teaches at 92Y in NYC and is the social media & outreach director for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts.

You can find her on Twitter@LynnMelnick.

Brett Fletcher Lauer.

Brett Fletcher Lauer is the deputy director of the Poetry Society of America and the poetry editor of A Public Space, and the author of the collection A HOTEL IN BELGIUM. He is the co-editor with Lynn Melnick of PLEASE EXCUSE THIS POEM: 100 New Poets for the Next Generation and is the poetry co-chair for the Brooklyn Book Festival and lives in Brooklyn.

April 12, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Carol Rosenfeld: The Poet in Our Divided World

Recently I was asked to moderate the poetry panel at the 12th Annual Saints and Sinners Literary Festival, which was part of the larger Tennessee Williams Literary Festival in New Orleans this year, and I agreed. Then I was asked to write the description.

Bywater Books, June 2015.

I had an idea, but I couldn’t seem to articulate it in a way that satisfied me, which is what writing poetry is like for me, come to think of it. I kept thinking about the bewilderment I felt over events reported in the news, how I kept trying to map out the path that had led humanity to the place where we are now. Eventually I came up with the following:

“The Poet in Our Divided World. Poets, through their unique voices, can play many roles: healer, citizen, teacher, herald, the fool speaking truth to the king. Our world in tumult is in need of the poet’s counsel more than ever. How can poets make the greatest impact with their words?”

I was fortunate in my panelists: Scott Bailey (THUS SPAKE GIGOLO), Saeed Jones (PRELUDE TO BRUISE), Kay Murphy (Professor Emeritus at the University of New Orleans), and Brad Richard (HABITATIONS, MOTION STUDIES and BUTCHER’S SUGAR).

On March 23, five days before the panel was going to take place, and two days before I left for New Orleans, I stumbled across an essay by Toni Morrison in The Nation, entitled “No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear.” I opened the panel by reading from the essay. Morrison had written about feeling depressed and helpless, unable to write, after the presidential re-election of George W. Bush in 2004. A friend had called her, and hearing her talk about her dark mood, had responded: “No! No, no, no! This is precisely the time when artists go to work—not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That’s our job!”

Coffeehouse Press, September 2014.

I asked the panelists to comment. Brad Richard said that poets needed to “get in people’s faces about things that need to be said.” Kay Murphy said she had thought of the line, “Writing poetry is a political act.” Saeed Jones remarked, “My work is not separate from my life,” and went on to say, “Poetry serves to make sense of the unspeakable,” adding that “journalism and prose-writing can’t always go there.” And Scott Bailey said that “poetry shapes thought, which shapes culture.”

I had invited each poet to bring two poems: one of their own, that they would like to read to another person—a politician, a family member, a student, for example—in the hope of making them see or think differently about something, and a poem written by another poet that made them think differently about something—an event, a person, a place, a belief.

Scott Bailey read “Exit Ramp 69 in Edenville, MS” from his book, THUS SPAKE GIGOLO, and then read excerpts from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.”

Saying that “We need to begin to think as critically about law as we have about art,” Saaed Jones spoke about the inspiration for his poem “Don’t Let the Sun Set on You,” from his book PRELUDE TO BRUISE. Jones said he had read an article on “sundown towns”—referring to towns with signs posted stating people of color (the actual signs used a different term) had to leave the town by sundown. Saeed also read Shira Erlichman’s poem, “When I Woke Up to a Woman Screaming Help Out the Window and a Car Door” from the online journal, Winter Tangerine.

Kay Murphy read one of her own poems and one by Jenny Factor, from her book UNRAVELING AT THE NAME

Brad Richard said that his first poem, “Eye-Fucked,” about the murder of Nicholas West (from BUTCHER’S SUGAR) was about hate, and the second poem, “You, Therefore” by Reginald Shepherd (from FATA MORGANA), was about love, and that he would read both of them to Governor Mike Pence of Indiana.

Toward the end, I raised the question of people’s perception of poetry as something esoteric.

Sibling Rivalry Press, October 2012.

Brad Richard, speaking from his experience as chair of the creative writing program at Lusher Charter High School, suggested that we start teaching poetry to students early on. He said his students loved poetry—but he also knew of teachers who did not include it at all.

Saeed Jones saw part of the problem as being poets who only talk to other poets; he thought we needed to find opportunities to bring poetry into our cultural conversations. I think the Write All the Words! National Poetry Month guest blogs are one way of doing that.

Kay Murphy was troubled by what she saw as the “mental masturbation” that some young poets think of as poetry. Scott Bailey chimed in, comparing it to American idol. Bailey also said it was important to be aware of and to be shaped by literary predecessors.

Although I appreciate what Murphy and Bailey said, it seems to me that all writers and poets have to start somewhere. Bailey spoke of his work with patients at St. Mary’s Hospital for Children, as well as his work with prisoners, how when they see their voice, their words on the page, it validates their existence. The first step in the process is to put pen to paper. That can open the door to developing your craft through reading and learning from other poets.

While I was working on this blog I read in the Poets House March 2015 newsletter, in A Note from the Poets House Executive Director (Lee Briccetti), “…I have encountered many people who cling to a prayer, a song, or a line of verse as if it were their last handhold on a cliff…even though they swear not to like poetry.”

Poetry is powerful. We hunger for it, though we may not recognize that it is poetry we want.

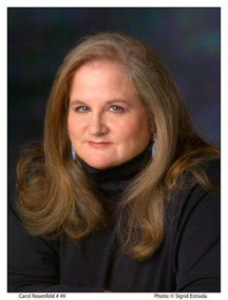

Carol Rosenfeld.

Carol Rosenfeld is an accomplished short fiction writer and poet—though it’s been a while since she participated in a poetry slam. Soon Bywater Books will be publishing THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY, the first novel by this writer described as “A fruit cup in the whole-grain world of literary fiction”. A Juris Doctor (she studied at night school!), she is kept very busy as the voluntary chair of the Publishing Triangle, which has been promoting LGBT literature since 1988. And that’s when she’s not at her day job, working for an organization that administers grants for the many colleges in the City University of New York.

She’s lived in New York since 1976, and can often be found at the opera—she has a growing fascination for Wagner (and quite a few questions, too).

April 11, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Lucy Frank: Delighting In Words

Somewhere in the endless middle of writing TWO GIRLS STARING AT THE CEILING, I was taking a walk on our dirt road in upstate New York when the sky went dark and the wind began to blow. As I got to the top of the huge open field we call Harry’s Hill, thunder rumbled, first in the distance, then closer. As drops began to fall, and lightning lit the sky, the thought came: I could go stand in the middle of the field. If I’m struck down by lightning, I won’t have to write the book.

Schwartz & Wade, August 2014.

TWO GIRLS is a novel in verse about two young women whose lives are upended by chronic illness. It takes place in a hospital room. I gave the girls the same disease I’ve had since I was nineteen, Crohn’s, a sometimes terrible disease no one wants to have and no one wants to talk about. It’s also called Inflammatory Bowel Disease. No surprise no one wants to talk about it.

Exactly, insisted the same voice that voted for the lightning solution. You spent so much of your life trying to deny you have the thing. Now you’re going to spend how many years wallowing in the experience? Why would anyone want to read that book? Why would anyone want to write it? And what gave you the grandiose idea of writing it in poems?

I’ve always read poetry. But I never thought of myself as a poet. I still don’t, really. I think of myself as someone who delights in words: the feel of the vowels in my mouth, the music, or the playful silliness in the sounds. I love to fuss and fiddle with them, mess around. The surprise of a pleasing cadence, a sly rhyme, the exact right word gives me the same sharp joy as coming upon a salamander in the spring woods, or hearing a woodcock’s crazy, buzzing mating call.

Both are joys I learned from, and shared, with my father, who loved the natural world and wrote poems of wit and grace, almost always in form. But from him I also learned to use words as indirection, smoke screen, obfuscation. Or, to use a word I’ve always enjoyed but never used: persiflage. In life, my father kept his feelings tightly wrapped. In his poems, he danced around them, dressed them in elegant or humorous disguise.

That was what I assumed I’d be doing when I first thought of writing the poems that morphed into the book. I saw a notice asking for original poems or stories for a new online magazine for teens living with chronic illness. I’d hit a bump in the novel I was working on, so I thought, I can do that. It’ll be a nice diversion. Within a few days I’d written a poem I called “After Seeing the Gastroenterologist.”

How ’bout a dog next time, instead of a doc?

With eyes that never tire of watching me,

ears utterly attuned,

an infectious doggy smile.

Who cares if he doesn’t smell that great

or take insurance, can’t write prescriptions,

do a colonoscopy, or save my life,

if it should come to that?

With a wag of welcome,

he’ll pad over, and after a polite sniff,

tuck his nose into my armpit

to check my temp,

Then clamber up beside me

and turn around three times

before, with a calm so total

it’s contagious, he settles in for our consult.

Poem after poem bubbled up, all well within my father’s comfort zone, even this rewrite of the side effects list in the brochure accompanying my most dreaded med:

A is for acne;

B, for buffalo hump, bald, bloated, beard;

C is cuckoo, cataracts;

D, deranged, depressed;

E, if it can’t run away, I’ll eat it;

F, I’m frantic, frazzled, frightened of getting fat.

But then there’s G,

for gets you better,

and that shining H. For hope.

The problem is,

what if I go straight to R, for ripshit,

before the steroids help?

Then I wrote something that surprised and scared me:

And suddenly

everything you thought you knew

you don’t. You’ve stepped off

the edge of your life

into

Sickland.

In an interview in Marin Magazine (November 2014), the wonderful poet Jane Hirshfield said: “Poems hover between inner and outer worlds. They’re messages holding the kinds of thinking and feeling we’re often too shy to speak aloud. The most powerful moments of our lives cry out for the deepening and acknowledgment that hard-to-find words can bring them. . . . They enlarge the range of what you can see and feel.”

When, shortly after writing “Sickland,” the lines came to me:

Sometimes I wish I could be just me

without my body

I’d found the message, to use Jane Hirshfield’s word, I didn’t know I’d been seeking.

In another interview, this one on NPR a few weeks ago, about her new book, TEN WINDOWS: How Great Poems Transform the World, Hirshfield spoke about compassion, and how poems “ . . . allow us to feel how shared our fates are. . . . Someone else has been here. Someone else has felt what I felt.”

My own poems kept coming. And with them, good girl Chess, and profane, pissed-off Shannon. Putting my lines in the voices of characters who were not me, or only parts of me, and giving them a story that is not my story, even if we share an illness, let me dare to get started. The poems gave me the freedom to jump from present to past, and between the inner and outer worlds. But mostly, the poems helped let me stick with a story — my story, however well-disguised — that felt too dangerous to look at too closely, or feel too deeply.

Hirshfield again: “Finding a poem is what lets me find a way through what feels like an impenetrable thicket. Poems are answers to the questions that can’t be answered.”

In the case of my two girls, and myself: How do you dare show yourself to the world and to yourself? How do you trust that people will see you for who you are inside, when you can’t trust your body not to betray or embarrass or shame you? How can you live your life when you’re never sure how you’ll feel? What do you do with the anger and discouragement? How do you ask for help when you need it, and still hang onto your pride? How do you keep on laughing? How can you remember, when things feel really bad, that it won’t stay that way, and that life will be happy again?

The compassion I found for my girls was what kept me writing. But we’re all of us caught in one thicket or another. I hope everyone who reads TWO GIRLS STARING AT THE CEILING will see something of herself or himself or someone she knows in Chess and Shannon and the people in their lives.

Lucy Frank.

Lucy Frank is the author of eight young adult and middle grade novels. Her first, I AM AN ARTICHOKE was a 1995 Publishers Weekly Flying Start. TWO GIRLS STARING AT THE CEILING received the 2011 PEN/Phyllis Naylor Working Writer Fellowship. It has been named a 2014 Best Teen Realism and Best Teen Friendship book by Kirkus Reviews and cited for outstanding merit on Bank Street College of Education’s Best Children’s Books of the Year. She and her husband split their time between New York City and their home in upstate New York.

April 10, 2015

National Poetry Month from Matthew Burgess: Let There Be Elephants, or What is a Poet?

When I walk into the 2nd grade classrooms where I teach poetry on Friday mornings, one of the first things I say is, “Repeat after me.” This might sound like old-school pedagogy, but our call-and-response is anything but: “I’m a poet / and I know it / I’ve got my whole life / to show it.” We snap in unison, then bring our fingers to our temples to activate the invisible switches of our imaginations. Sometimes I vary the chant or add an extra verse: “I feel it in the winter / I feel it in the spring / I feel it when I whisper / I feel it when I sing.” Though not much of a singer, I go for a big, ringing SIIINNNGGG! in the last line, and the young poets echo it back in a hilarious chorus. The point is to signal the transition to imaginative writing, to wake us up a bit, and to reinforce a truth that is often overlooked: all of us in the room are poets.

Enchanted Lion Books, April 2015.

Slow down, Fräulein Maria. What makes a person a poet?

I call these seven year olds poets in the same way that my Buddhist friend calls babies Buddhas, or in the way that Pablo Picasso asserted that “all children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once you grow up.” In other words, all the 2nd graders in the room possess poet-potential, and the surest way for them to access it is to believe wholeheartedly in their creative power.

Kenneth Koch had a hypothesis—that children know more about poetry than we often give them credit for—and he went into public schools to test it. What he discovered (and shared with the world in several exceptional books) is that children have plenty to teach us about the origins and usages of poetic language, and we would be wise to pay attention and to adjust our teaching methods accordingly. Koch was one of the founders of Teachers & Writers Collaborative, one of the first arts-in-education organizations in New York City, and I’ve been a poet-in-residence for T&W since 2001. I especially love teaching the early elementary students, because they continually surprise me, and they remind me again and again what a poet is.

Just last week, one of my 2nd grade students wrote this astonishing poem in response to E. E. Cummings’ “the sky was candy.”

Another student wrote about “puppies being born in rain drops,” and she was inspired by Cummings’ implicit permission (and mine) to place the poem on the page in a wildly inventive way.

During one of the season’s big snowstorms, another 2nd grade poet (who early in the residency asked me if “it was allowed” to make up words) wrote this poem using personification to describe winter.

Winter is a boy with rough weather.

Winter likes to play snowball fights

and destroy snow mountains.

Winter likes to eat snow burgers and drink

snowco-cola and hot snowcolate.

Winter likes to play snow and seek.

Winter lives in New Snowville, 35 miles from the snoway.

The snoway is in Snow City.

Snow City is in Snow State.

Snow State is in Snow Country.

Snow Country is in SNOWORLD.

Snoworld is in Snowuniverse.

So a poet is someone with a vivid imagination who takes pleasure in language. A poet is happy to leap over logic in order to dance to the music words make. If I read a line aloud—Elegant elephants eat eel eggs every Easter—poets don’t insist, “That doesn’t make sense!” On the contrary, poets want to jump in and keep the song going; they are likely to tell you about the jaguars jumping to Jupiter to drink the jujube juice. The movies in the minds of poets are still vivid, and their aliveness to language serves as perpetual refreshment to the image-making, song-creating mechanism embedded in everyone. Some of us let it fade from disuse, or from unintentional abuse at the hands of “grown-ups” who are all-too-often preoccupied with common sense, avoiding mistakes, and of course, test preparation.

Edward Estlin Cummings was someone who held on to this poem-making capacity for his entire life. He was born into a family that celebrated poetry, and both his parents nurtured his artistic development from a very young age. His mother, Rebecca, dreamed that her baby boy would grow up to become a poet, and she began recording his earliest attempts in a book titled “Estlin’s Original Poems.” As I write in my newly released picture book biography of the poet, ENORMOUS SMALLNESS: A Story of E. E. Cummings (illustrated by Kris Di Giacomo), Estlin’s first poem “flew out of his mouth when he was only three.”

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo, courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books.

Once he learned how to write, Estlin took over and began keeping his own youthful journals, often decorating his poems and stories with drawings of elephants in the margins. I try to capture Estlin’s playful way with words in the following passage, citing the “great circus of his imagination.”

ENORMOUS SMALLNESS tells the story of E. E. Cummings’ development as a poet, and for me, part of the secret of his poetic gift was his ability to retain his childlike vision until the very end. That is to say: playful, open-eyed, and alive to the details of everyday life. The internationally celebrated poet lived in a tiny flat on a half-hidden cul-de-sac in Greenwich Village, collected miniature elephants, and famously wrote: “may my heart always be open to little birds who are the secret of living / whatever they sing is better than to know / and if men should not see hear them men are old.”

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo, courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books.

The 2nd grade poets keep me young. Like E. E. Cummings, they know a thing or two about “the secret of living,” and they remind me what a poet is, or should be. A poet is a person who loves the way words sound and look, and who engages in the art of making objects out of words. It is the making that matters most—the great ongoing circus of the imagination. When my students finish their poems, they often hand them over to me without hesitation, and someone always requests that I read his or her poem aloud to my other classes. They get that the magic is in the making and the sharing, and in all of the enormously small ways that poems can wake us up.

And, by the way, if you are curious why Cummings’ name does not appear in lower case letters, read here.

Matthew Burgess.

Matthew Burgess teaches creative writing and composition at Brooklyn College, and he has been a poet-in-residence with Teachers & Writers Collaborative since 2001. His first full-length collection of poems, SLIPPERS FOR ELSEWHERE, was published by UpSet Press, and a children’s book titled ENORMOUS SMALLNESS: A Story of E. E. Cummings is newly released from Enchanted Lion Books. Burgess recently received his PhD in Literature from the CUNY Graduate Center, and his dissertation, titled “The Vastness of Small Spaces: Self-Portraits of the Artist as a Child Enclosed,” explores the significance of childhood space in the autobiographical works of Virginia Woolf, Denton Welch, Anne Sexton, Frank O’Hara, Alison Bechdel, and others. His poems, photographs, and essays can be found online at www.matthewjohnburgess.com.

April 9, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Sarah Crossan: Poetry Is Mine and Poetry Is Yours

My debut was a verse novel called THE WEIGHT OF WATER. I am proud of that book. It won awards and critics liked it. My parents liked it (which is not something every writer can say!).THE WEIGHT OF WATER is not a difficult book and it’s quite short – you could probably read it in two hours. And yet, even now, when I offer this book to friends or talk about it, the reactions from people can be rather startling.

Here is the standard response to someone being given a copy of THE WEIGHT OF WATER: The person flicks through the first few pages, blinks, swallows hard, and mutters, “It’s, uhh, poetry?” The question is paired with a look terror, because what this person is really trying to say is, “I hate poetry. Everyone hates poetry. Why would you write a book like this? Are you some kind of sicko?”

Bloomsbury USA Childrens, January 2013.

The truth is that most people don’t feel comfortable with poetry. They haven’t read any since high school and back then poetry was hard and boring. Plus, the poems they read had nothing to do with them.

And I understand this because I used to feel the same way. I went to an all girls convent school, and you’d think they’d have made an effort to have us study poems by women – just a few women. But no. I hardly realized women could even write poetry because we studied mostly Shakespearian sonnets and works by John Keats and Wilfred Owen and I remember feeling so lost, so disconnected, so uninterested and actually, so stupid. I remember wondering how I could fake my way through the exams by appearing to understand what I was reading. I read the Spark notes. I knew what the poems were meant to be saying and I knew how I was meant to be reacting. I did well in English throughout high school despite these fears, so I must have been pretty good at faking it. Many students are.

But now I look back, I’m starting to think that the problem wasn’t really that we were studying Shakespeare or other dead, white men; the problem was that reading poetry was a purely intellectual pursuit. And this is where we do our young people a disservice. In schools, poetry is usually chopped up into small pieces. Students are asked to explain poems. To dissect. To master. And surely this is the easiest way to kill anything for young people. Because that’s not how art should be approached. We don’t look at paintings and begin by chopping them up. We don’t listen to music in bite-sized chunks and get teenagers to explain away the melody. With most other art forms we allow people to respond emotionally first and foremost. We allow people to be led by their hearts. How does this song make you feel? And this is the purpose of art; to draw out our humanity by provoking emotion. And yet when it comes to poetry we don’t allow this. We want to know what it all means and if we can’t comprehend it entirely, we have somehow failed. What better way to put people off something than by telling them they aren’t smart enough for it?

Bloomsbury USA Childrens, May 2015.

And I find this so sad because I truly believe that poetry belongs to everyone. Why do I believe this? Well, poetry is the first language we speak. When we were toddlers we could string together rhymes and songs long before we could articulate feelings or desires. It was how we learned to talk. One, two, three, four, five/Once I caught a fish alive… Poetry is built into our DNA.

This is why I wrote my latest novel, APPLE AND RAIN, about a girl struggling with life but who finds peace and ultimately a way through her problems, by writing poetry. And she does this because she has an inspiring teacher, a character called Mr Gaydon, who offers his students poetry, not as something to be conquered, but as a vehicle of self-expression and nothing more. Because what else is poetry if not a way in to ourselves? A way to feel less alone.

The rules of poetry are manmade. They aren’t like math with formulas and answers. The rules of poetry are fluid and changing and that change is down to those who write. So why shouldn’t the writer be me? Why shouldn’t the writer be you? Poetry belongs to us all. We started speaking by reciting poems and everyday we plug ourselves in to our phones and listen to music with lyrics that are made up of poetry. It is everywhere. And it is ours.

Perhaps the academics would like us to believe that poems belong to them, but we can’t let this happen. When we feel poetry slipping out of our hands we must snatch it back and use it. We must write poems and read them. And above all, we mustn’t be afraid. We must use it however we like and ignore anyone who tells us that we are doing it wrong.

Sarah Crossan.

Sarah Crossan is the author of THE WEIGHT OF WATER, which was short-listed for the Carnegie Medal, as well as BREATHE and RESIST. She grew up in Ireland and England, taught English in the United States, and now lives in Hertfordshire, England. Visit her online at www.sarahcrossan.com, on Twitter at @SarahCrossan, and on Facebook at www.Facebook.com/Sarah-Crossan.

April 8, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post From Stacy Clark: Rhyme & Rhythm: How Poetic Stories Engage, Encourage & Empower Young Readers

Growing up, my son, Dylan, would always ask me at least 100 questions a day. Answering them was the most fun I’ve ever had because my answers inevitably led to more of his amazing questions! Reading together included more inquiries about the world and more conversations about how things work. But there was one time of the day when we both preferred to just read the words of a book and marvel at the pictures. These tales signaled bedtime by slowing down the pace of the text with rhythmic stanzas and big, persuasive illustrations that pulled us into the story. Inevitably, by the last page of one of these bedtime pleasers, Dylan’s eyes would close as he turned to fall fast asleep. I recognized the magic in those lyrical stanzas and wanted to create them myself.

Inspired by Dylan’s response to his favorite rhyming books, I embarked on a ten year-long journey to publication. Apart from reading as a parent, my Pre-K classroom has served as an ideal “literary laboratory” for gauging the appeal of rhyming stories and the word plays that often follow. It’s also been an observatory for testing my personal thesis that the benefits of rhyming adventures extend well beyond enhancing literacy skills—they actually promote “emotional intelligence,” or what I often refer to as happiness, contentment and creative expression.

University research has demonstrated that young children pay more attention to rhyming words than regular words because poetry delivers a predictable repetition of sounds and momentum that invites engagement with both text and illustrations. With greater focus on a story, I’ve noticed that students eagerly recount poetic storylines with friends and family, sometimes even performing the adventure with classmates and siblings. This interactivity, spawned predominantly by rhyming picture books, helps kids to build social connections, a sense of humor and a sense of place within a community. Classic stories like Dr. Seuss’s THE LORAX, for example, earn big points with readers each year because the tale’s irresistible rhyme demands attention. Any underlying message then becomes an easy sell.

Here’s a recap of THE LORAX for those of you who haven’t read the book in a while:

As The Truffula Trees are being decimated by a greedy industrialist known as a Once-ler, The Lorax complains that a “Gluppily Glup” and a “Shoppily Shlop” are harming the Humming Fish. The headstrong and reckless Once-ler harvests all of the colorful natural resources that his business relies on and, in the end, both he and everyone else is faced with a disintegrating landscape devoid of life. Only one seed from a Truffula Tree remains and on serious and considered reflection, the Once-ler has the good sense to hand the seed (the future) to the The Lorax.

Random House Books for Young Readers, August, 1971.

And, here’s a verse from THE LORAX:

“SLUPP!

Down slupps the Whisper-ma-Phone to your ear

and the old Once-ler’s whispers are not very clear,

since they have to come down

through a snergelly hose,

and he sounds

as if he had

smallish bees up his nose.”

Imagine the enjoyment of reading this gem to children! Everyone is cheering the hard work of THE LORAX to defeat the Once-ler’s diabolical mission. Dr. Seuss’s genius is that readers of all ages embark on a literary adventure together and celebrate at the end. Children who eagerly anticipate each turning page of THE LORAX must welcome the chance to laugh out loud and, at the same time, learn something new about what they care about and what they might stand up to protect.

Stacy and her son, Dylan, in Truro, MA.

Perhaps the overall appeal of rhyming texts for young readers is that poetry elicits positive emotions. The fluidness of the words can be hypnotic, relieving one’s mind—at least temporarily—of stress and anxiety.

Marc Bracket, Ph.D., Director of Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, was quoted in this September 11, 2013 New York Times Magazine article entitled, “Can Emotional Intelligence be Taught?” by Jennifer Kahn.

“Something we now know, from doing dozens of studies, is that emotions can either enhance or hinder your ability to learn. They affect our attention and our memory. If you’re very anxious about something, or agitated, how well can you focus on what’s being taught?”

Here, Beckett refers exactly to the area where I have observed the value of poetry to be the most relevant. Rhyme seems to be a mental and physical elixir of sorts, enabling kids—even those most easily distracted—to find enjoyment in the experience of storytelling.

My first book, WHEN THE WIND BLOWS, is the story of a seaside town, where homes, harbors, hillsides and highways are powered by offshore windmills. Its poetic stanzas, combined with the beautiful double-page canvases created by Brad Sneed, delivers technology and science in a most appealing and accessible manner. Reading WIND to audiences this year, I’ve enjoyed watching children and their parents smiling together, as Dylan and I so often did, and I find myself squarely present in the moment.

Stacy Clark.

Stacy Clark is a mother, teacher, environmental geologist and writer based in Dallas, TX.

April 7, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post From K.A. Holt:

My job as a writer comes in many forms. I write (hopefully) action-packed sci-fi middle grade novels in prose. I write (hopefully) funny and heartfelt contemporary middle grade novels in verse. I write humor essays for a parenting website. Sometimes I pretend to be Geoffrey Chaucer confused by modern technology. I also write as part of Typewriter Rodeo, a quartet of poets who create spontaneous poems on vintage typewriters.

Chronicle Books, 2014.

Each one of these jobs informs the other, bleeding into each other like watercolors. Sometimes you don’t actually want the pink and green to mix, but they do anyway. More times than not, this blending is a good thing.

I often spend my days working on a draft of a verse novel – struggling with character creation and plot development, making sure the imagery is appropriate for the audience, and that I’m showing and not telling the actions of the moment. It’s something I love to do, and it’s something that can be so, so hard. After a day spent beating myself up over clichéd metaphors and half-developed characters, sometimes the best thing to do is to sit in front of the TV and allow myself to go braindead. But often, the best medicine is a Typewriter Rodeo gig.

My fellow poets and I meet at the gig (maybe a wedding or a corporate party) and we set up our typewriters. People don’t know what to expect from us, and we don’t always know what to expect from ourselves, or from them. A person in line will give us a word or a phrase and we will then write a poem – on the spot – and deliver it within minutes. It’s a crazy thing to try to do. And it’s wonderful.

In the next two typed pages, I’ve tried to convey why writing poems on the typewriter is such a fun exercise, and why I think, overall, it can help make anyone a better poet.

K.A. Holt with the Typewriter Rodeo.

Kari Anne Holt is the author of several middle grade novels in verse including HOUSE ARREST, (Chronicle 2015), RHYME SCHEMER (Chronicle, 2014), and BRAINS FOR LUNCH: a zombie novel in haiku. She is also the author of the forthcoming space western RED MOON RISING (Simon & Schuster 2016) and MIKE STELLAR: Nerves of Steel, a nominee for the 2014 Connecticut Library Association Nutmeg Book Award and the 2013 Maud Hart Lovelace Award. Kari is a member of Typewriter Rodeo, a spontaneous poetry-writing quartet based in Austin, TX.