E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 7

June 22, 2015

Pride Week Guest Post from Jean Copeland: Teacher’s Pride: Why It’s Important to be Out in the Classroom

I had the great pleasure recently of teaching my debut novel, THE REVELATION OF BEATRICE DARBY, in the alternative high school where I’ve taught English literature and creative writing for nine years—great pleasure and great fortune. After all, coming of age lesbian romance fiction isn’t part of most high school curriculums. So yes, I’m fortunate to work here for many reasons.

Bold Strokes Books, April 2015.

The one that stands out every June is the fact that I’m allowed to be myself among faculty, staff, and students, a luxury indeed as LGBT teachers in many parts of the country still can’t imagine what’s like to be open at work. But it wasn’t always like this. I carried a lot of left-over baggage about revealing that part of my identity when I began teaching as a second career in 2006. Bush was still president, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was alive and well, and so was the Defense of Marriage Act, so I had to be practical about it. Back in the 80s, I’d gone to heroic lengths during my four years of high school to conceal my secret identity from my classmates, well aware I’d be the target of ridicule and rejection if they’d ever found out. The idea of being the target of teenage scorn wasn’t any more appealing to me at thirty-seven than it was when they were my peers.

A year later, however, I had come to a crossroads in my career when I decided to offer a Gay and Lesbian Film and Literature English elective. Brazen, maybe, in that pre-Edith Winsor era, but I knew my boss would go for it as he’s a huge supporter of multi-culturalism and diversity in the classroom. But would my students? I’d had a few gay and lesbian students who would be excited about a course that represented their universe for the first time in their schooling, but how would the rest of the students respond? Would the straight kids even take the class? All those questions paled in comparison to the final one that reared its ugly bed head: Did this mean I was going to have to come out to my students?

I flashed back to the gay kids who were mocked and teased while I was nestled deeply and securely in my closet in high school, and my knees knocked, my forehead beaded with sweat. That could be me, except I wasn’t their peer anymore; I was their teacher. Any educator will tell you there is always that moment of trepidation on the first day of any class, especially with a room full of adolescents eager to challenge the establishment. Now I was about to add kerosene to that already potentially combustible situation of setting boundaries and earning their respect. But how could I teach a class about a culture of Americans who’ve struggled for decades to live openly and with dignity if I remained evasive and secretive about my own life? I couldn’t, for myself and especially for the emotionally, and unfortunately, sometimes physically battered, LGBT students who were starving for a positive adult role model. It was either prepare for the inevitable or not run the class.

So I did what any self-respecting, middle-aged, aspiring-activist lesbian teacher would do: I ran the class and anxiously braced for the fallout. But there was none. No rude jokes, no emails from outraged parents, just a diverse group of students willing to read stories and watch films about a culture of Americans most had only heard about. I was truly amazed at how little my orientation mattered to the student body as a whole. Somewhere along the line, they’d shed the prejudices and ignorance of their parents and grandparents who may have believed gays were deviants, sinners, pedophiles, or any of the other asinine assumptions made through the ages. With little to no fanfare, I was open with my students and once again enjoying that exquisite feeling of emotional freedom that comes from living an authentic life.

However, the most important lesson I would learn was yet to be presented. By the end of the semester, it became clear that coming out to my students wasn’t at all about the final step in my own coming out process. It was far more profound. An openly gay student, Dana, who had been bullied throughout most of his junior high and high school careers, wrote in a journal assignment about the relief he felt realizing gay kids can “grow up to be normal and have normal lives.” I suppose to a child who had been tortured for so long simply for being himself, this revelation was a water-shed moment. That perhaps his self-image was going to change for the better after taking my class or his own future had become brighter were thoughts that filled me with joy and a sense of purpose. It was in my capacity as an educator, an “out” educator sharing my story, that I could help him make this possibly transformational discovery.

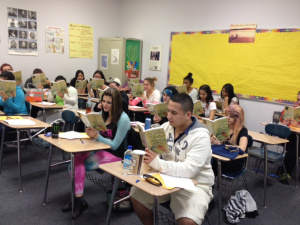

Jean’s students with her novel.

Teenagers are sometimes called self-involved, apathetic or complacent, and in some cases that’s true. While I’ve seen these less-than-admirable qualities in my nine-year teaching career, I’ve also seen compassion, reason, empathy and indignation, qualities that revive my spirit with hope for our country’s future, and especially for the nation’s LGBT community. As we read chapters from my novel, The Revelation of Beatrice Darby, in class, I smiled to myself at the outrage and incredulity my students expressed when the protagonist, Beatrice Darby, encountered each new conflict of prejudice, contempt, and injustice that a lesbian in the 1950s would typically face if she were out. It made me wish that my character, Beatrice, had people like this on her side when she was going through her search for identity. Hell, it made me wish I had.

Over the years, I’ve learned so much from my students. Young people have fresh ideas and seem to be aware of the basics in life we adults tend to forget over time, the importance of individual identity, fairness, and acceptance. They are the generation that finally gets it when it comes to gays and lesbians. They understand that people are who they are, and that if you are gay or lesbian or bi, it’s not a bad thing. I’ve discovered that many of my students identify as bi. Whether it’s truly a part of their identity or a reflection of their openness to new experiences, only time will tell, but the big take-away here is that today adolescents are more inclined to allow each other the freedom to figure it out openly rather than having to hide that part of their development as something shameful and worthy of derision.

As I finish up this school year, I’m doing so as a teacher and now an author. It’s through the candidness and sincerity of my students that I am realizing how powerful and important those two professions are in helping young people develop not only their intellects but also their fragile senses of self. If the detours and derailments in my own coming out journey have gotten me here, then I’ll be forever grateful for the ride.

Jean Copeland.

Jean Copeland is an English teacher and writer from Connecticut and the author of THE REVELATION OF BEATRICE DARBY, her debut novel published by Bold Strokes Books. Her fiction and essays have appeared in online and print journals including Dialogual, A Family by Any Other Name, WIPs Journal, T/Our Magazine, Sharkreef.org, Connecticut Review, Texas Told ‘Em, P.S. What I Didn’t Say, Off the Rocks, Best Lesbian Love Stories,and The First Line. Visit Jean at www.jeancopeland.wordpress.com

June 21, 2015

Pride Week Guest Post from Lesléa Newman: HEATHER HAS TWO MOMMIES, 25 Years Later

When I wrote HEATHER HAS TWO MOMMIES in 1988, I never dreamed it would be deemed a “classic” 25 years later. I never dreamed it would be banned, burned, defecated on, and read into the Congressional Record. I never dreamed it would be parodied by Jon Stewart, Conan O’Brien, and Bill Maher on national TV. Heck, I didn’t even think the story would ever see the light of day.

Candlewick Press, New Edition, March 2015.

The book wasn’t even my idea. The book would never have been created if not for a chance encounter. In 1988, I was walking down the street in Northampton, MA, which the National Enquirer had recently dubbed “Lesbianville, USA,” when an acquaintance stopped me on the street and told me she did not have a book to read to her daughter that showed a family like hers—a little girl with two moms—and that somebody should write one. She looked me straight in the eye, and I knew by somebody she didn’t mean anybody. She meant me.

Always one to appreciate a writing challenge, I immediately rolled up my sleeves and got to work. How hard could it be? Children’s books don’t even have a lot of words, I thought foolishly. Now when I think back, I’m reminded of a quote by Mark Twain. The story goes that an editor asked him for a three-page essay. He sent a telegram: “Need 100 pages? Give me 3 days. Need 3 pages? Give me 100 days.” In other words, writing children’s books may look simple, but it isn’t easy.

I went to our local library, checked out arm loads of picture books, devoured them, and began to write. Once I decided that the notion of “two” was going to be woven throughout the story, the words came easily. Heather has two hands, two feet, two arms, two legs, two pets, and two mommies. She brings two of her favorite things with her on the first day of school. There she learns that families come in all kinds of configurations and that as her teacher tells her, “the most important thing about a family is that all the people in it love each other.”

Writing Heather wasn’t hard, but her journey to publication, proved to be difficult.

I reached out to large publishers, small publishers, mainstream publishers, and alternative publishers. No one wanted to bring Heather into the world. One editor at a large New York City publishing house acknowledged that there was a need for the book as well as an eager audience for it, but he said he “wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole.”

Alyson Books, 20th Anniversary Edition, September 2009.

One day I was discussing this with my friend Tzivia, who was a lesbian mom with a brand new (gorgeous) baby daughter. One of us (we honestly can’t remember who) said, “Let’s do it.” Tzivia had a desk top publishing business (remember those?) at the time and so we decided the book would be put out by her business, In Other Words. We sent out a fundraising letter to the people who had signed up to be on my mailing list at poetry readings, and we raised about four-thousand dollars, all in ten-dollar donations (and remember, this was decades before Kickstarter). We found an illustrator and a printer, and by the time the books arrived on my doorstep, half of them were spoken for. Six months later, Alyson Publications took over and became the book’s publisher.

People tell me I was very brave to create a book about a child with two lesbian moms. I didn’t feel brave. I didn’t feel like I was doing something radical. I didn’t think my book would start cultural wars, cost New York City’s Chancellor of Education his job, or start heated discussions at school board meetings and around dinner tables all across the country. All I thought about was writing a book for the daughter of two moms so she could see a family like hers in a children’s book.

Many adults have embraced Heather. Many adults have rejected Heather. But what matters to me most is what children think of Heather. Like the little girl who sent me a letter saying, “Thank you for writing HEATHER HAS TWO MOMMIES. I know that you wrote it just for me.” And the little boy who crossed out the word “Heather” every time it appears in the book and put his name instead. And the little girl who sleeps with the book under her pillow every night. And the little boy who brought the book to his classroom for show-and-tell. That’s what matters most.

Children are not born thinking there is only one way to be in this world. They don’t have a pre-conceived notion that one type of family is better than any other. Children think, “Who are the people who love me? Who are the people who will take care of me?” These are the people in my family. The people who love me.

Many things have changed since 1989, the year that the first edition of Heather was published. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell has been struck down. The Marriage Equality movement has made great strides and soon the Supreme Court will render a historic ruling. The country of Ireland has just decided by a landslide popular vote to legalize same-sex marriage. Many high schools and middle schools have Gay Straight Alliances. It’s a new world.

And Heather has a new look. After the book went out of print several years ago, Candlewick Press re-issued it with a trimmed text and brand new illustrations. Now Heather marches confidently into her new classroom in her signature purple cowgirl boots with a big grin on her face. Heather is leading the way for a new generation, and I couldn’t be prouder.

Lesléa Newman.

Lesléa Newman is the author of 65 books for readers of all ages. Her titles include OCTOBER MOURNING: A SONG FOR MATTHEW SHEPARD (teen novel-in-verse), A LETTER TO HARVEY MILK (short story collection) and HEATHER HAS TWO MOMMIES (children’s book). Her literary awards include poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Artists Foundation. Nine of her books have been Lambda Literary Award finalists. From 2008-2010 she served as the poet laureate of Northampton, MA. Currently she teaches at Spalding University’s low-residency MFA in Writing program. Her newest poetry collection, I CARRY MY MOTHER was published in January 2015 by Headmistress Press.

June 2, 2015

Poetry & Rejection by the Numbers

So recently I was chatting with poetry friends about rejection, and when to give up on a poem. We were asking each other things like “when do you give up on submission?” Or “how many rejections does it take for you to know a poem just isn’t good enough?” I don’t know that there’s a specific number. So my answer is somewhere between “NEVAAAAAARRRRR!” and “Usually I get sick of the poem and realize it’s terrible before the number of rejections affects my willingness to send it out.” Given, I’m a bit of an egomaniac, but I maintain that all artists need delusions of grandeur on some level in order to function.

So there’s that. But I can give you some numbers. Because I’ve been doing this for a while and I’m still getting like 5-10 rejections a week because I do send out and I’m pretty sure that getting rejected is my job. Like, ratio of rejections to acceptances? Intensely on the R side. And those no’s sting. I’m not numb to it. And neither are you, probably.

The poem I usually mention in this context is “At that age when these girls become fairies” which I wrote in 2012, probably in the middle of the night, and began sending to magazines shortly thereafter. It was rejected by 62 magazines over two years before it was picked up by Abyss & Apex last year. Abyss & Apex also nominated it for a Pushcart. This is where the delusions of grandeur come in handy. Believing you’re awesome = not quitting = eventually maybe hopefully getting that piece you love published.

And here are some more numbers: I just had another piece, “A Nearby Fence, Pull,” published in Orbis Quarterly. This piece was written last year and it took about a year to place, over the course of 46 rejections, to place. “Peaches, Inhibited,” written in the fall of 2014, received 71 rejections (including one from Orbis) before finding a home in a forthcoming issue of TAB: The Journal of Poetry and Poetics. These two are poems that I thought would get snatched up right away, because I thought they were just edgy and cool and fun and tightly written. But, clearly, editors didn’t the same way. Until they landed on the desks of editors who DID.

And then there’s “Bermuda,” a poem that I wasn’t so sure about, but every once in a while I’d include in a packet. It only had 18 rejections, but these 18 rejections were spread out over four years. It eventually found a home in [PANK], which is a reminder every time I’m not sure about a piece that, perhaps, I should take a look at it from another angle, put on my game face, and try again.

And there have been TONS of poems that still haven’t found a home. Some of which didn’t find a home for a reason — they weren’t good enough. They didn’t speak to anyone but me. They stopped speaking to me. And those poems have gone in a drawer.

I think most of us eventually figure out what goes in that drawer eventually. Sometimes it’s a few weeks before you retire a poem. And sometimes it takes years of obsessing to kill those darlings. But the poems that you believed in on the day you first sent them to magazines and that you still believe in? Keep sending them. Because it could take a while, because the market is finicky, it changes, and it surprises you.

And, of course, there’s nothing more satisfying than an acceptance letter for a poem that’s been collecting rejections for years.

May 28, 2015

7 Questions I Always Ask +1 with Amanda Hocking, author of ICE KISSED and the Trylle series

It’s very exciting for me today to have Amanda Hocking on the blog for 7Q+1! She’s the sweetheart of self publishing and a prolific author, now publishing both traditionally and on her own. Check out her wonderful writerly insights below!

E. Kristin Anderson: What was the first spark of inspiration for your latest novel?

Amanda Hocking: Since it’s a spinoff series, the very initial spark began six years ago, when I was driving through the bluffs along the Mississippi River, and I thought, “I bet something magical could be happening up there, and we wouldn’t even know it.”

For this particular book – the second in a trilogy – the first scene I saw clearly in the book was the last scene of the book, but I don’t want to spoil that for you.

St. Martin’s Griffin, May 2015.

EKA: What kind of planning do you do before you start writing?

AH: My books always start the same way – with a pen to paper. I begin taking notes, doodling, scratching out ideas. Then I move on to outline, and with the Kanin Chronicles I did most extensive outlining, characters descriptions, and notes to date. I get all my character names figured out.

It’s after the outlining, I begin doing researching and gathering all the information I think I might need. Then once that’s finished, I get my playlist that I listen to writing picked out, and then I begin the actual writing.

EKA: If you could have lunch with any writer living or dead, who would it be? Or if you could get moderately tipsy with any writer living or dead, who would it be?

AH: I would have to be pick the moderately tipsy, since I would be too nervous to say much otherwise, and I would pick Kurt Vonnegut. He’s one of my favorite writers, and I just think he’d be a lot of fun to talk to over drinks.

EKA: What is the first book you remember reading and enjoying as a young reader?

Golden Books, Reprint Edition, January 2004.

AH: My very first favorite book when I was a kid was “The Golden Egg Book” by Margaret Wise Brown, which I eventually memorized and could recite on my own. The first book I remember by was a copy of Jaws by Peter Benchley from a garage sale for a nickel when I was eight, and I loved it.

EKA: If you could go back and time and tell your teen self ONE THING AND ONE THING ONLY, what would it be?

AH: There are so many things I would tell myself. I guess what I would have to say would be, “Nobody cares how you live your life, so live your life how you want.”

I mean, of course my mom and my friends cared about me, but I was so obsessed with what strangers might think of me, when I am now absolutely certain that none of them thought of me at all. (Which is okay. Most people are far too busy dealing with their own life to worry about what you’re doing with yours).

EKA: If you haven’t had a book challenged or banned, would you want this to happen to you? Why or why not?

AH: As far as I know, I’ve never had a book challenged or banned. I have had a couple messages from teachers saying that they would’ve liked to have their books in my classroom, but they won’t now because of the language and sexual content.

It doesn’t make me happy, exactly, but I understand in their cases where they’re coming from. It’s a choice I accept when I choose to include those things in my books, but I do that because that’s what I read as a young adult and that’s what I wanted to read. I swore more as a teenager than I do now, so for me, it feels unrealistic to have teens who are vanquishing monsters but never swear.

In my experience, banning a book only makes people want to read it more. However, I don’t approve of the practice of “banning” a book. A more population benefits everyone, and reading books of all varieties and flavors leads to a more information population.

EKA: What kind of book do you really want to try to write, but haven’t ever attempted? And what do you think is holding you back?

AH: I’ve always wanted to write a true crime novel, ala Ann Rule. There a lot of real injustices in the world that could benefit from having more light shed on them, and that’s a big part of what makes me so nervous to tackle something like that. It’s real lives I’d be talking about, and I just don’t feel qualified to write about it.

St. Martin’s Griffin, January 2012.

EKA: How has your approach to writing changed since you published your first book? Or, how has it not, and why do you think that is?

AH: In a lot of ways, I write the same – I write what interests me, I outline beforehand (although my outlines and notes have gotten more extensive as I go along), and I tend to write a lot in a relatively short amount of time.

The biggest difference for me is that now along with the characters, I have the readers in my head as well. I’m more conscious of how my words effect readers, and I’m more deliberate with my characters and the actions they take.

It’s been over five years since I first started publishing, and in that time, my life has changed dramatically, and I’ve grown and changed a lot as a person. I’m more aware of the fact that I’m writing for young adults, primarily girls and women, and the fact that my characters can potentially be role models for them. Now it has become important to me to showcase romance in a more egalitarian way.

Amanda Hocking.

Amanda Hocking is The New York Times bestselling author of the Trylle trilogy and a lifelong Minnesotan. After selling over a million copies of her books, primarily in eBook format, she became the exemplar of self-publishing success in the digital age.

Website: http://smarturl.it/AHWebsite

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/amandahockingfans?fref=ts

Twitter: https://twitter.com/amanda_hocking

Tumblr: http://amandahocking.tumblr.com/

May 26, 2015

New Magazine News!

It’s been a fruitful month for me!

Over the past several weeks I’ve received contributors copies of some really fantastic magazines. I’m so proud to have my work in current issues of Hotel Amerika, Fourteen Hills (for the second time — they first published me in 2007!), and Orbis Quarterly (also a second time — they first published me in 2010) — and to be printed alongside some really wonderful writers and artists! I hope you’ll consider buying an issue and supporting these wonderful publications!

Hotel Amerika Issue 13, Winter 2015.

Fourteen Hills 21.2, 2015.

Orbis 171, Spring 2015.

May 18, 2015

Going Home Again: My Visit to Westbrook High School

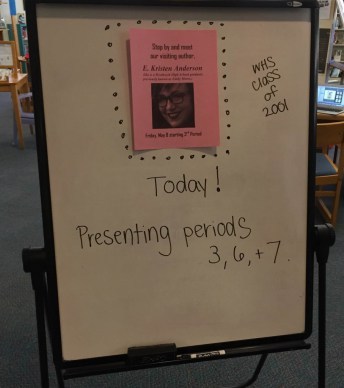

School visits always leave me inspired. I am so inspired by the students who attended my sessions on May 8th at Westbrook High School. Yes, THAT Westbrook High School. From whence I graduated.

Me outside the library. I spent a lot of time in the library not doing homework and tricking the librarians who didn’t know what blogging was into letting me blog because nobody knew what blogging was yet. Sorry not sorry.

A sign at the library! With my face on it!

Westbrook has changed a lot over the years. I ran into some of my old teachers who now were working out of different classrooms. The teacher’s lounge is in one of the old art room. (You guys, they have SNACKS in there. SNACKS! And BOOKS and MAGAZINES! Also SNACKS!) And so many of the teachers I spent time with have since retired (which is fair, since so many of those teachers also taught my dad, so, I’m guessing they paid their dues and whatnot). And while my locker hasn’t moved and the library is still right where it always was and the kids still hang out in the lobby before and after school, the faces at Westbrook High School are different. There’s so much more diversity there, ethnicity and otherwise, which made my talk extra rewarding, since my talk was about the literary canon, contemporary poetry, and community.

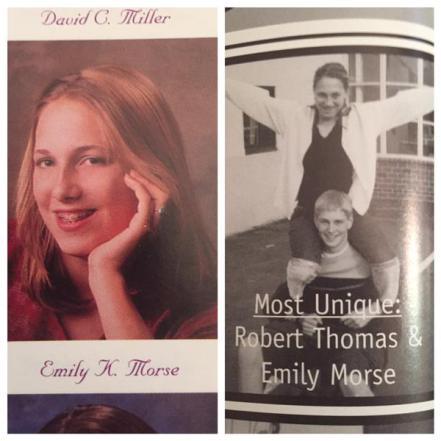

Snaps from my high school yearbook. MOST UNIQUE IS NOT A THING. And every student I talked to at WHS heard about why it’s not a thing.

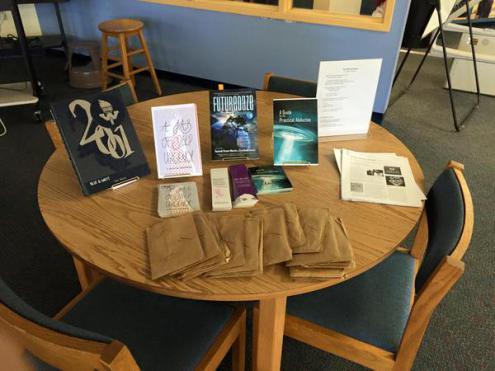

I read poems by LaToya Jordan, Lisa Cheby, Alyse Bensel, Care Santos (trans. Lawrence Schimel), Roger Reeves, and others. I read some of my own poems from A GUIDE FOR THE PRACTICAL ABDUCTEE — two of which I envisioned taking place in and around Westbrook High. I talked about the voices we value, how our own voices are important in our communities, how art is a space for building community, and how what we read affects all of this. And, obviously, about how poetry is wicked fun and not just for dead white guys and antiquated language.

This is me outside my home room. I have no idea what’s in there now but I used to do the crossword in the morning in here, like a proper nerd. Yes, Mom, that’s where your crosswords went in the late 90s.

Some amazing students from the middle school walked over and brought me a copy of their literary magazine, which is such an honor. All of the classes who attended had wonderful questions, both from students and teachers. (Y’all have no idea how great it is to have questions, let alone thoughtful questions, at the end of a talk. Crickets are the worst.)

I left some treats at the high school. I hope everyone enjoyed them. PS yes I’m in the yearbook next to a current WHS social studies teacher—try not to use that against him.

Another amazing gift at WHS was having two of my former English teachers (both now retired) come in to see me speak. Both of these women were a part of my growth as a young writer and reader. This was such a privilege, and one I’d imagine not many writers get to experience. Add to this that my grandmother (another WHS graduate) also came to my first session of the day and got to see what I do. It made my day extra special.

Me with my old locker. Yes, I remember my locker number; no, I won’t remember the conversation we had ten minutes ago.

Of course I wandered around the halls and took pictures of all the things. There’s a certain hometown pride that you never do shed, no matter how terrible or crazy your high school experience was.

The gym. There are no words for how much I hated gym class.

And even as I snapped a picture of the bleachers, closed, BLAZES spelled out in blue and white facing the basketball court, I understood why folks would think I was nuts to be in that building, again, on purpose. Some of my friends reacted with shock when I told them I was visiting my old high school. “You’re so brave!” they said. Or “why would you want to go there?” Well, here’s the thing: No matter how terrible my experience was when I was in high school, I might have the power to make some students have a less terrible time, and that makes every bad day worth it. In fact, before I even got back to the house that afternoon, one of the teachers had a blog post up quoting a student from the middle school:

“I liked that she told us she had been bullied, but she is now a successful author, because I was bullied too. If she can work through it, so can I.”

And that is why I went back. Not for the selfies. Not to sell books (though I did sell a few, THANK YOU!). Not to tell my old history teacher that I still have stress dreams about her class (though I did, sorry not sorry). I went back because kids need to hear that there’s another side. I’m here and you can be, too, whatever your other side looks like. Poets and writers and artists, go visit your old classrooms. Knock on the doors. Teens need hope and, I’d like to think, that art is hope.

April 30, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Megan Fernandes: Persona Poetry and Feminist Poetics

In my college classroom this past spring, I taught Adrian Matejka’s THE BIG SMOKE, a collection of persona poems in the voice of Jack Johnson, the early 20th century African American boxer. Johnson had a colorful and complicated legacy. For many, he was a symbol of liberation, a chance for black masculinity to be perceived as something mythological in the humiliating wake of the Jim Crow era. Yet for those who knew him well, he was horrific in his physical and verbal abuse against women. He proved to be unpredictable in his moods and portrayed by Matejka as quickly shifting from desperation to rage.

Penguin Books, May 2013.

For any good writer, this portrait is an impossible task. And yet, Matejka manages to capture, in what I will call one of the top ten best books of poetry I have read in the past five years, the complex, dynamic mosaic of a brutal fabulist, an unreliable storyteller, a man who was the son of emancipated slaves, a man who could only really be the circulation of his own image. In one of Matejka’s poems, he writes about the battle royal matches, violent unregulated fights where multiple African American men would be blindfolded and forced to fight for entertainment until one man was left standing. Matejka describes the experience through Johnson stating:

I didn’t know where

those punches came from, but I swung

so hard my shoulder hasn’t been right

since because the man said only

the last darky on his feet gets a meal.

This is what persona poetry can do.

I always think of persona poetry in conversation with the conventions of dramatic monologue and epic verse. It offers voice, stylization, and a keen sense for dramatic as opposed to lyrical writing. Things happen in first person, often in the present tense. The immediacy of the language could not be further from the reflective, epiphanic whimsy of so much lyrical poetry. Persona poetry is almost like writing for the stage. It is close to what Linda Williams has called a “body genre,” a way of directing sensation to your skin, particularly horror, suspense, or arousal.

Graywolf Press, October 2007.

Yet, the 21st century iteration of the epic also holds weight here. I think of reading Alice Notley’s DESCENT OF ALETTE or Matthea Harvey’s Robo-Boy poems from her collection MODERN LIFE or Anne Carson’s THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF RED, the third person personas spilling out onto the page, whizzing into rooms, sweating, lighting cigarettes, wondering at dandruff. I still see Carson’s young Geryon place an empty fruit bowl on his head like a helmet, such a poignant scene when we learn that the fruit bowl’s consistent emptiness throughout his childhood is a metaphor for his mother’s neglect. Geryon is a queer red monster. Robo-Boy is exactly what he sounds like. Yet there is nothing cheeky or cute or precious in the magnificent rendering of these emerging, hybrid subjects. Instead, these figures or personas challenge us to imagine multiple forms of being, eating, weeping, smelling, etc.

All these poets ask us, what does it mean to have a different sensibility? Different linguistic reflexes? What does the “poetic” mean when not filtered not through human consciousness? Or in Matejka’s case, through black consciousness during an era where a black man couldn’t light a cigarette for a white woman because it was seen as too intimate? How would one write intimacy within this context? It’s easy to imagine our poetry of unrequited loves and remorses, but what does reading about different forms of desire, vulnerabilities, and melancholy mean if you’re that queer red monster? Or that Robo-Boy? How does it help us develop not only a critical empathy, but also, a chance to be embodied in some other experience?

Tightrope Books, March 2015.

Persona poetry is often taught as a poetry of “masks” with the ability for the reader to experience both the subject-position of the writer and the (usually) historical figure they wish to ventriloquize. And yet, “masks,” feels too easy and clinical for what persona poetry can actually accomplish.

In my recent book of poetry, THE KINGDOM AND AFTER, a lot of poems explore the legacy of empire and certain patterns of Indian diaspora across the globe. But mostly, it’s really about imagining an era after Kinghood. It wants to visualize the crashing of certain landscapes, a wasteland of Kingdoms that failed in their attempt to preserve particular colonial and patriarchal values. The book, THE KINGDOM AND AFTER, is bursting with queens, daughters, female usurpers of thrones. The title comes from Shakespeare’s King Lear, a man with a troubling relationship with his daughters to put it lightly.

In the book, there are three persona poems called the “Corinne” poems. Corinne is not quite a historical figure, though her name is similar to Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter. She is both grounded in the 21st century mundane of math class and Macy’s, but she is also able to spin molecules when bored, cradles gravity on her spine, and is the descendent of centaurs. Corinne wants to be a gay boy. She owns a hair straightener and reads Yeats religiously, and yet, she also eats cardboard and has tendons like lassos. In short, she is a creature between imaginations. Her insecurities are as much about her blue eyebrows aging into a silvery grey as they are about the ocean growing.

Some teachers (particularly male ones) throughout the past few years found this set of poems puzzling and strange. One told me that there were so many wonderful ways to speak openly and directly about Empire and History and Violence (mentioning Lowell and Auden in particular). In reality, there is no open and direct way to write about any of those subjects, and moreover, only a certain person would feel the kind of privilege or gall to think themselves capable of writing a comprehensive or direct account of Empire or History or Violence. These things are not representable. They cannot be uttered directly. Language often fails them. And I’ll tell you, there is more at stake for me in a single line of Sylvia Plath’s poem, “Cut,” than in most of Lowell’s poetry. That’s just my opinion, but hey, I don’t want to read Lowell on my death bed.

And for some, Corinne, like Robo-Boy or Geryon get dismissed as “cute.” But as I teach my students in class when referencing a terrific essay on cuteness by Sianne Ngai, “cuteness” is about power. Your desire to squeeze and cuddle is also your desire to dominate and domesticate. When cute things stop being docile and sweet and cuddly, when Geryon reads Heidegger, when Robo-Boy overhears his parents talking about his “off-switch,” when Corinne, the descendent of a centaur, scrutinizes the marriage of her parents, things change. We witness a group of subjects with a reawakened agency. No longer the muse, these figures become our thinkers and sinners and anti-heroes. This is a type of feminist poetics, and this is also what makes persona narratives so powerful.

Megan Fernandes.

Megan Fernandes is a poet and academic. She received her PhD in English at the University of California, Santa Barbara and holds an MFA in poetry from Boston University. She is the poetry editor of the anthology STRANGERS IN PARIS (Tightrope Books) and is the author of two poetry chapbooks: ORGAN SPEECH (Corrupt Press) and SOME CITRUS MAKES ME BLUE (Dancing Girl Press). She has been published or has work forthcoming in the Boston Review, Guernica, Memorious, Rattle, Black Lawrence Press, Redivider, and the California Journal of Poetics, among others. Her first full length manuscript, THE KINGDOM AND AFTER, was published in March 2015. In the fall of 2015, she will be an Assistant Professor of English at Lafayette College.

April 29, 2015

National Poetry Month: LaToya Jordan Interviews Don Tate

Hello readers! It’s my pleasure to introduce two of my favorite writers today. Austin author/illustrator Don Tate has this fabulous new book out about George Moses Horton, a slave poet from North Carolina. And LaToya Jordan is about to blow your minds with her debut poetry chapbook, THICK-SKINNED SUGAR. I couldn’t possibly do a National Poetry Month feature and not have both of these wonderful writers on board. So here they are, in conversation. Get ready to be moved, y’all:

LaToya Jordan: As a Black American poet, after hearing about your book I felt slightly ashamed I’ve never heard of George Moses Horton. His story is so fascinating–the first African American poet to be published in the South while he was he was still a slave! How did you learn about George? What attracted you to his story?

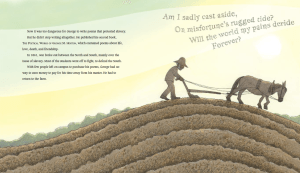

Peachtree Publishers, September 2015.

Don Tate: Honestly, I hadn’t heard of George Moses Horton either until a friend and critique partner suggested I write about him. I’m glad he did, Horton has an important story to tell. His determination to learn how to read really spoke to me, as it happened at a time in this country when African American literacy was devalued—even outlawed in some colonies.

In THE LIFE OF THE AUTHOR, WRITTEN BY HIMSELF, Horton weaves a theme of literacy through his story, and that attracted me. Reading is important, and Horton’s life is a testimony to that. Horton was physically enslaved well into his sixties. Learning how to read as a child paved the road to his intellectual freedom—something that no one could take away from him, even as he toiled away behind a plow in his master’s fields. Literacy among slave communities threatened the entire slavery system. That’s why teaching a slave to read was outlawed. Reading led to slavery’s demise. Literacy is knowledge and knowledge is empowering. When you consider the myriad of issues facing young African American males today—dropping out of school, incarceration, crime, homicide, poverty—there’s no doubt in my mind what higher literacy rates could do to combat some of these issues. While it’s never my intent to clobber my readers over the head with so-called important messages, I do hope young readers will pick up on the underlying theme of how reading can change destinies.

LJ: What was your research process for the book like? How did you find information about George and how long did it take to have enough background to tell his story?

Kessinger Publishing, Reprint Edition, May 2010.

DT: I began telling Horton’s story in the same way that I began telling Bill Traylor’s. I drew a timeline. As I researched, I plotted the events of Horton’s life—his birth and death dates and everything in between. For research I started with Wikipedia, which is not exactly the best research tool, but it was a start. My primary source was THE POETICAL WORKS OF GEORGE M. HORTON, THE COLORED BARD OF NORTH CAROLINA, TO WHICH IS PREFIXED THE LIFE OF THE AUTHOR, WRITTEN BY HIMSELF. In the prefix, Horton offers a very short but detailed account of his life. At times it was a challenge to read and to comprehend. Published in 1798, it is written in a flowery, archaic English. Horton often used words like “thee,” “thou,” “twas,” and “ye.” He was often wafted “on pacific gales, above the storms of envy.” I had a lot of deciphering to do.

The Wilson Library at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was a valuable resource in telling the story. Whenever I had a question, they responded with a wealth of information: books, illustrations, photographs, website links. In addition, curators at the Historic Hope Plantation and the North Carolina Museum of History read early manuscripts and offered feedback. I referred to several other resources including many of Horton’s poems. I even discovered some estate papers where George’s master assigned him a value of $208.00.

LJ: You’ve illustrated so many wonderful books and written a book that you didn’t illustrate. With this book you’re both the author and illustrator, how was this process different? Which came first for you, the words or the pictures?

Lee & Low Books, April 2012.

DT: The words came first. I need words to tell a story visually. For me, words inspire images. Following my research (which continued throughout the entire process), I wrote, edited and revised the manuscript many times before sketching. In retrospect, that may not have been the most efficient way to work. My sketches caused word changes. Word changes caused more changes in the sketches. It was a back-and-forth moving target. And that was before the book even sold. Once the manuscript was acquired by Peachtree, the back-and-forth dance continued. In fact, revisions continued practically until the day we sent the book to be printed.

Finishing Line Press, February 2015.

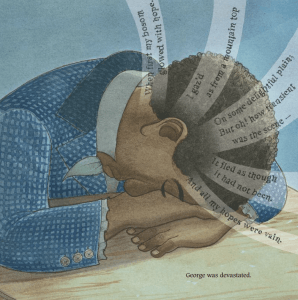

LJ: One of my favorite images from the books is when George is devastated that his master won’t free him. His head is on the table and lines from his poems look like as if they are coming out of his head. Did George’s poems help inspire you when writing and illustrating his story? Do you have a favorite poem or lines from a poem you can share?

DT: Thanks! With that scene, I really wanted to convey Horton’s frustration with his situation. He wanted freedom badly, but his master would not allow that to happen. I could not find the right words to communicate that feeling. I soon realized that body language, not words, would best deliver the emotional punch. I acted out the scene and took a picture of myself with my head down between my arms. That became the reference for the painting.

As far as Horton’s poetry, I love it. His words are honest, heartfelt. I wanted the reader to hear his words, his voice. The problem was that while I had plenty of his poetry to use, Horton’s complex antiquated language clashed with my simple storytelling style. So instead of using George’s poetry as dialog within the text, I made his words part of the illustrations.

Courtesy of Peachtree Publishers/Don Tate.

A favorite poem:

THE GOSPEL FEAST

Rise up, my soul and let us go

Up to the gospel feast;

Gird on the garment white as snow,

To join and be a guest.

Dost thou not hear the trumpet call

For thee, my soul, for thee?

Not only thee, my soul, but all,

May rise and enter free.

This is a hymn that he composed one morning before his Sabbath services. I have no idea what he is saying here, but isn’t it beautiful?

LJ: I was moved by your author’s notes at the end of the book. You touch on some serious topics: originally being ashamed of the topic of slavery for your work, how the publishing world could do a better job at telling African American stories beyond slavery, and literacy rates of African Americans. I think readers are going to be inspired both by George’s story and by your note at the end. Speaking of inspiration, what’s next for you? Any books currently in the works?

Courtesy of Peachtree Publishers/Don Tate.

DT: Thank you again. I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the response to my Author’s Note. It seems to have resonated with people as much as the story itself. It’s interesting to me because I wasn’t trying to say anything moving or provocative. I simply made a statement about my personal journey. Words are powerful. I’m thrilled when people really get my words.

What’s next for me? I’m illustrating several more nonfiction books. The next one, WHOOSH!, written by my critique buddy Chris Barton, is the story of inventor Lonnie Johnson. I have many more books on the horizon that I am under contract to illustrate, several that I have written too. I am blessed.

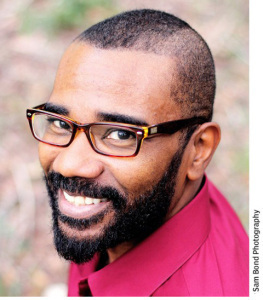

Don Tate. (Photo by Sam Bond.)

Don Tate has illustrated numerous critically acclaimed books for children. In 2013, he earned an Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor Award for his book IT JES’ HAPPENED: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw (Lee & Low Books). Visit his website at www.dontate.com.

LaToya Jordan. (Photo by Nisha Sondhe.)

LaToya Jordan is a writer from Brooklyn, New York. Her poetry has appeared in Mobius: The Journal for Social Change, MiPOesias, Radius, and is forthcoming in Mom Egg Review. She is the author of THICK-SKINNED SUGAR, a chapbook available from Finishing Line Press. She received an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University Los Angeles. Her biggest fans are her husband and pre-schooler. Visit her at latoyajordan.com.

April 28, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Karen Skolfield: On Ekphrasis

If you want to get the attention of 4th graders, show them a painting of a man made out of produce. I click to the PowerPoint slide of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s The Emperor.

The Emperor, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1590.

“It’s a guy!” “But there’s fruit!” “I see grapes!” “What is THAT?” one student says, and points, I think, to the artichoke shoulder, or maybe it’s the fig-ear.

“You’re right, he’s made out of fruits and vegetables. Crazy!” I say, and shake my head. “Do you think this is a recent painting or one that was made a long time ago?”

The kids have fun answering. We’ve just looked at Kehinde Wiley’s 2005 painting Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps, part of a series in which Wiley re-sees famous poses and scenes using black models. So they’re feeling pretty confident that the Arcimboldo painting is the same: an old theme made new, given fresh meaning.

They’re not disappointed when I tell them The Emperor is 425 years old. In fact, they seem delighted – maybe they hadn’t realized humans were making art then, so sure are they that the world prior to their births consisted of amphibians crawling from the ooze. “We need to write about this guy,” I say, and they gamely grab their poetry journals.

Zone 3 Press, October 2013.

I’m visiting a class in Fort River Elementary in Amherst, Massachusetts. Amherst is in western Massachusetts, closer to New York and Connecticut than Boston. A 2-D “tree” in the Fort River lobby, made of construction paper handprints, shows the many skin tones in the first grade; more than half of the students are people of color, with some thanks to the five colleges in the area that attract international grad students and professors. Nearly 40 percent of the students qualify for free or reduced lunches, slightly above the state average, which seems at odds for a town of just 38,000 with more cultural and arts events per capita than many major cities.

The fourth graders in front of me have their poetry journals open. Some don’t want to hear my prompts and have started writing and really, who am I to stop them. But most like the Q&A poetry form. I remind them: “I’m going to ask you a few questions about Arcimboldo’s The Emperor, and your answers are the poem.” After each question, which I say aloud, I wait a few minutes as they write. They have a handout to look at if they wish, with the questions on them – a good strategy for kids who have trouble attending to auditory instruction, or for kids who want to leap ahead.

After each painting and poem, I ask if anyone wants to share: it’s mostly boys volunteering by 4th grade, and though I’ve never counted, I have the sense that more white hands go up than non-white. I even this out as best I can by calling on kids who haven’t raised hands. This teacher’s done a good job; almost everyone is willing, even eager, to read, even the shy ones, even the ones for whom English is their newest language.

Radiante, Olga Albizu, 1967.

This is not my first time using ekphrastic poetry prompts in elementary schools, so I’ve learned to keep it simple, keep the poems short, talk about the artwork before we write about it. I’ve learned not to give them choices about multiple pieces of artwork to write about – the act of choosing can be stress-inducing to students who have attention or anxiety issues (I made a 3rd grader cry once by asking him to choose between two pieces of art). I’ve learned that whichever girl sits closest to me is often unwilling to speak up, so I take a couple of minutes after the class so she can read without the whole class listening. I’ve learned, most importantly, that they love writing and poetry at this age, with few exceptions and very little eye rolling. I don’t know what these teachers today are doing, but it’s making my work easy.

*****

When my kids started kindergarten, I – and all the parents – got some pressure to volunteer. The new class needs a room parent! The new class needs math helpers! Soccer coach, PGO president, savings account director, book fair assistant, fantasy-area overseer, costume designer, nut-free snack scheduler, really, the list of things I did not want to do went on and on.

So with no small amount of guilt, I dodged most of the heavy volunteering but baked heartily for all school events. Then my oldest son brought home his first poems. Oh hey. I perked up and sent an email to his teacher: “Want me to visit?” She replied, I think, before I hit SEND.

I’ve written very few ekphrastic poems – maybe three. But as I considered what to do with two classes of 3rd graders, I decided this would be a way into writing that could be both inward and outward looking – and any chance to bring more art into their lives seemed a great bonus. I’m no art history major, though, so Googling and hive-mind questions on Facebook have been great sources for background and for artists I’d never encountered.

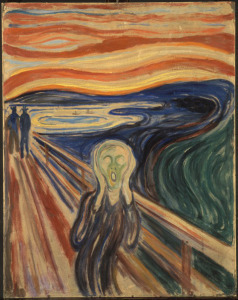

The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893.

The classes last about an hour. I begin with a brief explanation of ekphrastic poetry, and I tell the kids they now know a word that their parents probably don’t know. The kids love this. Occasionally a teacher will pipe up and say s/he didn’t know the word, and the kids love that, too. Then I show a slide, talk about the painting or sculpture by asking open-ended questions to the kids, and read the ekphrastic poem aloud. Some of the art and poem pairings I’ve used include Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and John Stone’s “Three for the Mona Lisa;” Pieter Brueghel’s Two Monkeys and Wislawa Szymborska’s “Two Monkeys by Brueghel;” Georg Baselitz’s Die Mühle brennt (“The mill burns”) and the poem of the same (German) name by Richard Matthews; a selection of Degas paintings and Philip Levine’s “M. Degas Teaches Art And Science At Durfee Intermediate School – Detroit 1942;” and more. It’s helpful if I know a little about their art classes – if they’ve been studying or imitating some abstract artists, I’ll throw in an abstract painting by Olga Albizu or Georgia O’Keeffe. I love sculpture: Xu Bing’s found-material phoenixes are always a hit, or Alberto Giacometti’s tall figures; go playful with sculptures from Hung Yi’s “Fancy Animal Carnival” series or abstract with Joan Miro’s Moonbird. Or throw in a sculpture built from Legos. The kids will go nuts.

After I read a poem, we’ll talk. I’m continuously amazed by what they see and hear and puzzle through. Take the boats in Edvard Munch’s The Scream – have you noticed those boats? Trust me, if you ask some 3rd graders about the painting, one will spot the boats and come up with some dynamic ideas about what those boats are doing and contrast the cool and calm in the distance with the worry and foreboding in the foreground. Okay, the kids probably won’t use the words “foreboding” and “foreground,” but if you use those words a few times, the kids will eventually use them, too. Ask them about the vines growing out of the woman in Frida Kahlo’s Roots – their answers will range from wonderfully creepy sci-fi to some inkling of how emotionally complex the lives of 5th graders can be. Tell them about Kahlo’s self portraits and how this is probably one – give them her medical background – and they will make all the connections you’d hoped for, and more.

Then students write poems while the adults in the room help out kids who need extra attention. For Arcimboldo’s The Emperor, here are the prompts/questions I use:

Let’s assume that this changed skin is new, and that the emperor can’t see himself. Help him out and tell him what he looks like.

The emperor is shocked at your description of him! Try to think of a way to make him feel better about himself. What can you say to him to make him happier, maybe even proud?

You know, but haven’t yet told the emperor, what happens to fruits and vegetables and flowers that are left on the counter for a few days. What do you think will happen to the emperor now? Your answer to this question is the ending of the poem.

It’s good, as you prepare a class for elementary kids, to consider their needs and maturity level. Make your prompts as racially and gender diverse as possible; ditto for the poets. Leave out images that are violent or contain nudity, even for the older kids; their teachers will never forgive you if you get that wrong. Leave out poems that are too complex or too long or touch on mature subjects.

Roots, Frida Kahlo, 1943.

Think like a kid growing up in America: for the Wiley painting, I (luckily) asked kids to come up with three POSITIVE words to say about the subject, a black man astride a horse. Even though the subject in Wiley’s painting has much the same expression as Napoleon does in the famous Jacques-Louis David painting it’s modeled after, the words the kids first came up with were all negative: “scary” especially stood out to me, in a class in which half the kids are people of color. We’d already prepped by talking about how Napoleon had let his people starve to fund his war effort and how this new leader envisioned by Wiley was going to do better, and still they came up with “scary” for the black man. Yikes. But by saying “nope, I want POSITIVE words for him,” they eventually got off the scary thread and found kinder words.

(Of course, as I write this, I think: Is it okay for leaders to look scary? Is that a positive attribute? The students didn’t use that word for Napoleon, but could I have turned this into a moment in which a black man is leading his soldiers into battle in a way that makes the “scare” factor work?)

I taught that particular class two months ago, and here I am, still thinking about it. I’m scheduled to teach another class on ekphrastic poetry, with a new set of kids, in two weeks. After that, another school. And another. Each time, I’ll learn something different, come home jazzed by student poems and ideas.

Let’s face it: I’m not really Room Parent material. But if poetry’s involved, sign me up.

Karen Skolfield.

Karen Skolfield’s book Frost in the Low Areas won the 2014 PEN New England Award in poetry. She has received fellowships and awards in 2014/2015 from the Poetry Society of America, New England Public Radio, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Ucross Foundation, Split This Rock, Hedgebrook, and Vermont Studio Center. www.karenskolfield.com

April 27, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Christina Stoddard: Seeing and Being Seen

As a teenager, I wrote a lot of stories about hidden girls. Girls with secrets. Girls with mystery and allure, two things my real self markedly lacked, or so it seemed. The truth was that I had plenty of secrets. But they tended toward the ugly and brutal.

Since poetry itself seemed mystical—how many times did the other kids complain it was a code they couldn’t read?—maybe it was inevitable that by eighth grade I had started adding line breaks to my stories as I wrote them down. I already wanted to be a writer, but poetry seemed even further out on the tree limb, more delicate and dangerous.

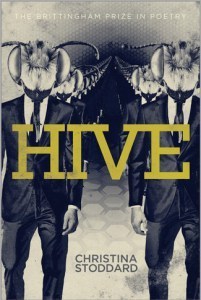

University of Wisconsin Press, March 2015.

As an adult, when I started writing about things that happened to my teenage self, I was still writing poetry but I wasn’t doing it to hide anymore. That was my insurrection.

The poems in my recently-released first book, HIVE, are mostly plainspoken. Which is not to say they aren’t lyrical and musical and deliberately composed. But I fully intended HIVE to be an every-person book. To be accessible and understood.

To that end, I borrowed a few techniques from fiction writing. Unlike many books of poetry, HIVE has a single narrator throughout: a high school age girl who lives in a very poor neighborhood and who belongs to the Mormon church. She thinks these things define her, and in many ways they do.

The majority of the poems are autobiographical. I’ve read a few interviews where writers say in retrospect that they wrote the book they wish they’d had when they needed it. A manual of sorts, a survival guide. That wasn’t my intention while working on HIVE, but over time the book steered itself that way. And I do mean “steered itself”—I believe there’s a certain amount of unconscious will at work when I write. If I try to grip the wheel too hard, the words on the page come out as bloodless as my white knuckles.

I didn’t hit on the idea of my teenage narrator until most of the poems in the book already existed in draft, and when I had them all laid out on the floor in a semicircle around me, I was struck by the thought that these poems could all be coming from one speaker. Suddenly there she was: a persona who was braver than I ever had been, sharper than I ever was, and with a wider lens—a touch of omniscience to improve the pacing.

The book follows this teenage girl through several story arcs. She wrestles with the violence she lives with—the Crips, the junkies, the neighbor kid who says he can kill her any time he wants. Her realities lead her to question the God she believes in, wondering why He would allow the world to be this way.

I was raised in a devout Mormon family. No caffeine, no swearing, no clothing that revealed the shoulders or even a hint above the knees. I remember how adults were always trying to impress upon me that I had a purpose in life and God had a plan for me. When I said yeah, I know, I’m a writer, they responded with quizzical looks. No, they said. Your highest purpose is to marry and raise your children in the Gospel. This is foremost above all other things.

Teenage girls have so many disguises. I chose goodness and duty because they kept me hidden. Some secrets make you mysterious and alluring. Some just make you a freak. I knew which kind mine were.

The second poem in the book takes place during a slumber party. One of the girls tells the others that she heard you can tattoo with ink from a regular ballpoint pen, and they dare each other to try it.

Every teenager flirts with violence. Especially once they realize they are capable of violence.

We always talk about the first verse of Genesis, but what about the one after that? “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” What is it like to live every day staring into the darkness on the face of the deep?

It took me a long time to figure out how to write about violence. I tried many different ways. For a while in my twenties, I gave up entirely after a fellow student in my creative writing class said I should just stop, because my poems were unbelievable, as in not credible, as in they had to be made up. With about ten words, a person I hardly knew had erased me. I made the mistake of believing in those ten words more than I believed in my own. I hadn’t yet learned that lots of people are going to try to tell you what you can and cannot write, and those people are usually morons with miniscule imaginations.

Still, experiences from my adolescence wouldn’t let me go—both my own and the ones I was caught up in secondhand. Perhaps in the beginning, I thought writing would help me figure out why these things happened. But I never found an answer. Later I learned there’s a word for this relentless asking of why: theodicy. The paradox that both God and evil exist, and how to reconcile that in our minds.

So I wrote HIVE to make hidden things seen. I wrote it for other teenage girls who believe they are alone. Because sometimes in highlighting an individual experience, a collective voice emerges. One person says This happened to me. And another adds Me too. And then more. Me too. Me too. Me too.

There is real power in being seen. In fact, having the book out there in the world is forcing me to be seen in ways I wasn’t entirely ready for. Every time I stand in front of an audience, it is like I am peeling off everything that protects me. It is raw and beautiful and intimate, just the way communing with a book is supposed to be. It is also scary. We are not sailing in safe waters, the audience and I.

Poverty is another kind of unseen violence. It is also erasure. When you are poor, people with good intentions often want to save you. But they rarely see you for who you are. They expect you to say thank you, and then they expect you to be quiet.

Likewise, when you have a different language, a different holy book, a different looking family, or a funny-sounding name, you get hammered down by other people who seem to want you to go away. You are taught to keep silent about yourself.

HIVE is my way of saying No to all of that. And if you don’t like the book, that’s okay. It just means I didn’t write it for you. The only thing I can do is trust that the people who need it will find it, and they will make their own way out of hiding.

Christina Stoddard.

Christina Stoddard is the author of HIVE, which won the 2015 Brittingham Prize in Poetry (University of Wisconsin Press). Originally from Tacoma, WA, Christina earned her MFA from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, where she was the Fred Chappell Fellow. Christina is an Associate Editor at Tupelo Quarterly and a Contributing Editor atCave Wall. She currently lives in Nashville, TN where she is the Managing Editor of a scholarly journal in economics and decision theory. Visit her online at www.christinastoddard.com and on Twitter at @belles_lettres.