E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 5

September 10, 2015

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from David Oppegaard: Literature of the Obscene

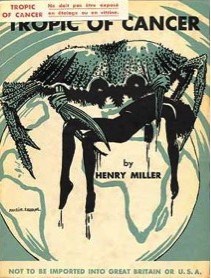

TROPIC OF CANCER, the novel by the American author Henry Valentine Miller, was first published in Paris, France in 1934 but was not published in the United States until 1961. The novel, which was immediately viewed as an important work of literature by many authors and critics, features a plethora of f-bombs, c-bombs, French prostitutes, and casual sex. Judged to be too “obscene” for publication in the United States and Great Britain, it even came with the warning “NOT TO BE IMPORTED INTO GREAT BRITAIN OR U.S.A.” on the bottom line of its front cover, as if the contents of the book itself were so toxic that the pure and upright citizens of the United States and Great Britain would forever be corrupted by what they viewed inside it.

Original Cover for Tropic of Cancer.

When TROPIC OF CANCER was finally printed in the United States by Grove Press in 1961 it caused a legal ruckus regarding what was and was not considered pornography: over sixty obscenity lawsuits were leveled at bookstores all across the country, so many suits that the book’s publisher hired a lawyer to help every bookstore facing prosecution for simply selling the book. Finally, in 1964, the U.S. Supreme court overruled state court findings and declared TROPIC OF CANCER to be non-obscene. Good honest red-blooded Americans could now purchase TROPIC OF CANCER without worrying about hearing a knock on their door or their immortal souls being corrupted by its inflammatory words.

The concept of obscenity, of something being obscene, can be applied broadly to anything that is found to morally repugnant to a large majority of people—like killing a human baby—but is, as often as not, used in reference to sex. The idea that the depiction of sex in a novel alone is worthy of the label “obscene” seems rather tame in our post-Fifty Shades of Grey modern era but it was books like TROPIC OF CANCER, along with evolving societal mores, that helped created the artistically unfettered world of modern Western fiction possible.

But what actually happens in TROPIC OF CANCER? Not a lot, really. The novel is essentially a free floating first-person philosophic meditation. “Henry Miller”, a fictional avatar of the novel’s author, describes his life as a struggling author in Paris during the late 1920s and early 1930s. Characters come and go. There’s a lot of talking and screwing and wine. If plot can be said to be a chain of events that directly impact each other, like dominoes falling in a line, TROPIC OF CANCER is basically without a plot at all. This is by design, of course, since the events and characters of the novel serve primarily as a sounding board for the narrator’s existential musings. “Henry Miller” is hungry, poor, and perpetually trying to get intoxicated and/or laid. He’s the raw id expressed broadly, a caricature of the starving, lusty artist set loose on a city that encourages and abets his behavior.

Nothing in this (admittedly basic) summary of the novel suggests anything earthshaking enough to warrant a novel being banned in a country that prides itself on freedom of speech, does it? Well, part of this is that times have obviously changed—foul language and sex aren’t exactly as scandalous to your average American as they once were (in fact the most scandalous thing about TROPIC OF CANCER nowadays is the blatant misogyny inherent in the way the narrator and his bros treat women, which I’m going to guess didn’t raise many eyebrows back in 1934). Yet putting the sex and the vulgar language aside, I get the feeling what really pissed off the moral establishment about TROPIC OF CANCER was how little “Henry Miller” gave a fuck about conventional societal mores and how brilliantly he expressed the pain of being a sentient human being in a troubled world.

“…the monstrous thing is not that men have created roses out of this dung heap, but that, for some reason or other, they should want roses. For some reason or other man looks for the miracle, and to accomplish it he will wade through blood. He will debauch himself with ideas, he will reduce himself to a shadow if for only one second of his life he can close his eyes to the hideousness of reality. Everything is endured—disgrace, humiliation, poverty, war, crime, ennui—in the belief that overnight something will occur, a miracle, which will render life tolerable. And all the while a meter is running inside and there is no hand that can reach in there and shut it off.”

In TROPIC OF CANCER “Henry Miller” says a lot of the shit most of us are thinking but unwilling to say aloud, or even admit to ourselves. He’s the prophet, the wildman. He’s the guy at the party who’s willing to call bullshit on the host when everybody else is content to stare into their drinks and enjoy a proper dull evening.

Flux Books, September 2015.

If the cultural establishment found TROPIC OF CANCER truly obscene, it was because the dark truths it spoke to butted up against their own preciously guarded notions of self-importance and control. I’ve noticed that the kind of folks who seek to ban books in schools and libraries are rather uptight (“Henry Miller” would probably suggest they need to get laid on a regular basis) and prone to believing they know what’s best for everybody else. They’re loud. They’re bossy. They write letters and show up with grammatically dubious signs at protests. They’ve failed to grasp that literature, and culture in general, is a never ending conversation that occurs between all humanity throughout every generation. Seeking to silence a voice or two in that immense conversation isn’t going to change the entire oceanic current of human evolution—it only reveals your own personal insecurities and a lack of tolerance for other viewpoints. You’re not going to prove anything by telling somebody to shut up.

But maybe if you write a book…

“I am going to sing for you, a little off key perhaps, but I will sing.”

-TROPIC OF CANCER

David Oppegaard.

David Oppegaard is the author of THE FIREBUG OF BALROG COUNTY out September 2015 from FLUX.

David is also the author of the Bram Stoker-nominated THE SUICIDE COLLECTORS (St. Martin’s Press), WORMWOOD, NEVADA (St. Martin’s Press) THE RAGGED MOUNTAINS (eBook) and AND THE HILLS OPENED UP (Spring 2014 from Burnt Bridge). David’s work is a blend of science fiction, literary fiction, horror, and dark fantasy. He holds an M.F.A. in Writing from Hamline University and a B.A. in English from St. Olaf College. He works at the University of Minnesota and lives in St. Paul, MN.

You can visit his website at davidoppegaard.com

September 8, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Mark Stevens: Give it a Rest

Note to the would-be banners of books:

It isn’t going to work.

Follow-up note to the would-be banners:

In fact, it has never worked.

Sure, caused a fuss and raised a ruckus, but it didn’t work.

Midnight Ink, September 2015.

Final easy-to-understand note to the would-be banners:

Every time you step forward and demand that a book be kept out of a library or school, I think the following thought:

I wonder what that author has to say and wants us to hear?

You do know, don’t you, that there is no such thing as ‘banning’ books, right?

You can target a classroom or school.

You can target a public library.

But it’s not going to work.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, according to Wikipedia, THE CATCHER IN THE RYE was simultaneously the most frequently taught title in public high schools across the United States and the target of the most censorship campaigns. Today, J.D. Salinger’s novel has sold over 65 million copies and still sells roughly 250,000 copies each and every year.

Little, Brown and Company, Mass Market Edition, May 1991.

You’re after “sexually explicit” material? Offensive language? You don’t think a book is age appropriate? Too much violence? You think a book emphasizes, gasp, homosexuality?

Do you think banning a book from a library or school is going to stop the flow of information from creator to consumer?

Witness the mobile device, the World Wide Internet, the television, YouTube, podcasts and many other ways that an individual with something to say can express himself or herself and, in short, tell the world.

There is no longer any bubble of ignorance unless you really work at it—and I concede it’s possible for any individual to choose to encounter precious little, thought it may take work.

But that’s just it, it’s the individual’s choice—not the other way around.

My parents were both librarians. They both held master’s degrees, in fact, in library science. I was born in 1954 and hit the 1960’s at the perfect age, ten years old when we were cranking The Beatles in the back of the bus on the way to school. But even then, with hippies around the corner and free love, the taboos were sharply drawn. You got your hands on a copy of Playboy, you held onto it.

But no matter their spiritual outlook, my parents recognized that there was no stopping ideas.

They never took a book away from me—ever.

When I read THE CATCHER IN THE RYE, I met someone I would never have encountered in real life—and got deep inside his head. Reading CATCHER was one of those transcendent moments as a middle teenager, being swept away into a world and attitude that I could not and would not have experienced without those words on the page.

My family, suburban Boston parents and three boys, belonged to lots of places and groups—schools, church, Boy Scouts, you name it. I’d never encountered a guy like Holden who felt so alienated (though I guarantee it was only a feeling at the time, nothing I really understood). Reading that book was magic but I’m sure half of it sailed right over my head the first time around.

My parents didn’t care what I read—and I’m sure in some cases they didn’t really want to know.

They raised a kid to sort out the truth in a sea of information, not be fearful of certain truths.

Fiction or non, books are nothing more than ideas and experiences. You can’t limit expression.

Give it a rest, you book banners you.

Mark Stevens.

The son of two librarians, Mark Stevens was raised in Lincoln, Massachusetts. He graduated from Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School in the suburbs of Boston and from Principia College in Illinois. He worked as a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor in Boston and Los Angeles; as a City Hall reporter for The Rocky Mountain News in Denver; as a national field producer for The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour (PBS) and as an education reporter for The Denver Post. After journalism, he worked in school public relations before starting his own public relations and strategic communications business. He lives in Denver with his wife and has two grown daughters.

Mark is the 2015 Winner of the 2015 Colorado Book Award for Best Mystery, and the Colorado Author’s League Winner for Best Fiction.

Where to find Mark Online:

Official Website | Twitter | Facebook | Purchase the Allison Coil Mystery Series Online | Goodreads

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Mark Stevens: Give it a Rest

Note to the would-be banners of books:

It isn’t going to work.

Follow-up note to the would-be banners:

In fact, it has never worked.

Sure, caused a fuss and raised a ruckus, but it didn’t work.

Midnight Ink, September 2015.

Final easy-to-understand note to the would-be banners:

Every time you step forward and demand that a book be kept out of a library or school, I think the following thought:

I wonder what that author has to say and wants us to hear?

You do know, don’t you, that there is no such thing as ‘banning’ books, right?

You can target a classroom or school.

You can target a public library.

But it’s not going to work.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, according to Wikipedia, THE CATCHER IN THE RYE was simultaneously the most frequently taught title in public high schools across the United States and the target of the most censorship campaigns. Today, J.D. Salinger’s novel has sold over 65 million copies and still sells roughly 250,000 copies each and every year.

Little, Brown and Company, Mass Market Edition, May 1991.

You’re after “sexually explicit” material? Offensive language? You don’t think a book is age appropriate? Too much violence? You think a book emphasizes, gasp, homosexuality?

Do you think banning a book from a library or school is going to stop the flow of information from creator to consumer?

Witness the mobile device, the World Wide Internet, the television, YouTube, podcasts and many other ways that an individual with something to say can express himself or herself and, in short, tell the world.

There is no longer any bubble of ignorance unless you really work at it—and I concede it’s possible for any individual to choose to encounter precious little, thought it may take work.

But that’s just it, it’s the individual’s choice—not the other way around.

My parents were both librarians. They both held master’s degrees, in fact, in library science. I was born in 1954 and hit the 1960’s at the perfect age, ten years old when we were cranking The Beatles in the back of the bus on the way to school. But even then, with hippies around the corner and free love, the taboos were sharply drawn. You got your hands on a copy of Playboy, you held onto it.

But no matter their spiritual outlook, my parents recognized that there was no stopping ideas.

They never took a book away from me—ever.

When I read THE CATCHER IN THE RYE, I met someone I would never have encountered in real life—and got deep inside his head. Reading CATCHER was one of those transcendent moments as a middle teenager, being swept away into a world and attitude that I could not and would not have experienced without those words on the page.

My family, suburban Boston parents and three boys, belonged to lots of places and groups—schools, church, Boy Scouts, you name it. I’d never encountered a guy like Holden who felt so alienated (though I guarantee it was only a feeling at the time, nothing I really understood). Reading that book was magic but I’m sure half of it sailed right over my head the first time around.

My parents didn’t care what I read—and I’m sure in some cases they didn’t really want to know.

They raised a kid to sort out the truth in a sea of information, not be fearful of certain truths.

Fiction or non, books are nothing more than ideas and experiences. You can’t limit expression.

Give it a rest, you book banners you.

Mark Stevens.

The son of two librarians, Mark Stevens was raised in Lincoln, Massachusetts. He graduated from Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School in the suburbs of Boston and from Principia College in Illinois. He worked as a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor in Boston and Los Angeles; as a City Hall reporter for The Rocky Mountain News in Denver; as a national field producer for The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour (PBS) and as an education reporter for The Denver Post. After journalism, he worked in school public relations before starting his own public relations and strategic communications business. He lives in Denver with his wife and has two grown daughters.

Mark is the 2015 Winner of the 2015 Colorado Book Award for Best Mystery, and the Colorado Author’s League Winner for Best Fiction.

Where to find Mark Online:

Official Website | Twitter | Facebook | Purchase the Allison Coil Mystery Series Online | Goodreads

September 7, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Luke Reynolds: We Are All Icebergs

Every year in my middle schools classes, about the third day of school, I step up onto our radiator so I can point to a massive poster of an iceberg and talk about it with my students.

I begin with, “You are all icebergs. I am an iceberg. Every book we’ll ever read is an iceberg. ICEBERGS!” At this point, many students wonder aloud what is the matter with the thing in my head called a brain?. Some students allow their eyebrows to rise, understanding where we’re about to go. Some want to know if I have ever fallen off the radiator.

Puffin Classics Paperback Edition, March 2008

The iceberg analogy is incredibly useful when thinking of, reading, or talking about banned books. Because often, books are censored for what people label “outrageous” or “unacceptable” about the surface of the book. But deep down, way below the surface, every banned book I’ve ever read or taught has had, at its core, incredible incantations of love, empathy, and pleas for understanding and recognition.

Take Mark Twain’s THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN. When I used to teach 11th grade, I remember planning a field trip for our students to take a two hour bus ride from Connecticut to Harvard University, in Cambridge, so we could hear from renowned African-American scholar and educator Jocelyn Chadwick. She gave a riveting speech, followed by a funny yet piercing Q & A with our students. She defended the novel, talked about how it has been used as a powerful tool to fight racism and prejudice, and opened up about the controversy—coming from so many sides—about the novel.

Ember, Paperback Edition, January 2010

As Dr. Chadwick spoke, my eyes scanned the audience of my students, and on their faces I saw fascination. The novel’s controversial and heavily-banned history lit them up. The idea that a book could be thrown out of schools—historically, yes, but even recently as we’ve seen with Matt de la Pena’s remarkable book MEXICAN WHITEBOY in Arizona—does the opposite of stifling student interest and engagement. Instead, it enflames it.

My students in the audience that day wanted to know why people had banned HUCK FINN, who had fought against the bans, what Dr. Chadwick believed, what I believed, and—most importantly—what they believed.

Often, books like Huck Finn are banned because of their language. Even now, as I teach in a middle rather than high school, I see incredible books that I know students would love, yet I am also all too keenly aware of how many adults would see only as far as the language and stop there, not understanding the deeper purpose, message, and resonance of the book. Kids, it seems, have a far greater capacity to understand the core instead of stopping at the surface.

So before I climb down off the radiator, I explain some of this to my seventh graders, and I then ask, “Do we behave like icebergs?”

Consistently, their hands shoot up—ready to offer story after story, example after example, of why they do think we all behave like icebergs.

Blink, September 2015.

“This one time, my best friend kept saying she was fine but…”

“People dress like they are perfect and their faces say they have no problems but…”

“People don’t talk about ______________ but…”

And on and on. In a way, what we show one another all too often falls into that category of language. And language, all too often, has the power to obscure rather than elucidate. As George Saunders powerfully wrote about the genocide in Darfur, politicians wield language to hide atrocities and enable inaction.

In our day-to-day lives, we all sometimes wield language to hide our emotions and actions and thoughts.

In books, language acts as the tip of the iceberg, too. But there is one key difference.

With great novels—many of them banned—language is the first stop. Beneath the language, we have plot, and beneath the plot, we have characterization, and beneath characterization, we have tone, and beneath tone, we have mood, and beneath mood, we have soul. Every great novel has its own identity—its own soul. And while with one another we can obfuscate the deeper, truer identity we possess, with a novel that identity is there, on the page, waiting for us to uncover it if we only read with open minds and empathetic hearts.

With my students, I tell them that our 7th grade year is going to be all about this process of uncovering, reading with empathy and open-mindedness. And I remind them not to stop only at language. Not to see a word that is “bad” and think the whole book is “bad.” Not to hear a character’s comment and reject the deeper issues that character faces.

Because if we do, then we ban the book from speaking to us and reaching us and changing us.

We already do this far too much with one another. And one way to learn to censor and ban one another less and learn more is to practice with books. If we allow ourselves to hear the deeper story of a novel, empathize with its characters, live its plot, than the more we’ll learn to dig deeper with each other, too.

I climb down off the radiator, ready to begin another year of 7th grade literature and life. But before we stop talking about icebergs, I quietly share a secret hope with my students: that by the end of the year, more ourselves might stretch above the surface, more of who we really are might—however cautiously—reach up and reveal itself.

And beyond any state scores or testing or grades, if my students can learn to read beneath the first layer of language with books, and bravely risk more layers of themselves, than maybe as a classroom of learners we will all be a little less judgmental and a little more empathetic. And deep down in my own soul as a teacher and writer, this is the only standard I really care about.

Luke Reynolds.

Luke Reynolds currently teaches seventh-grade English in the public school system in Harvard, Massachusetts. He and his wife, Jennifer, have two young boys and a young dog who is intent on waking up those young boys as often as possible. Luke is a lover of writing, running, pancakes, hiking, and all things goofy. His website is www.lukereynolds.com, and he blogs at reynoldsluke.blogspot.com. His previous work includes nonfiction such as: BREAK THESE RULES: 35 YA Authors on Speaking Up, Standing Up, and Being Yourself; A CALL TO CREATIVITY; and IMAGINE IT BETTER: Visions of What School Might Be.

September 6, 2015

Banned Books Month from Marsha de la O: Three Stories of Silence

First, a question for you: Has anyone ever said, Why can’t you write a happy poem? Has anyone ever said, Now what kind of crazy depressing shit are you putting out there?

You could say banning books is a prayer to the gods of silence. You could say silence is enacted as propitiatory magic. Some books are banned before they’re written.

BOA Editions, September 2015.

Silence in my community and in my home:

Once a terrible crime happened in my neighborhood: a home-invasion robbery which became a kidnapping, the mother taken away in the middle of the night by an armed intruder. Our newspaper did not report it because it was too terrible. Also, because it was disjunctive; we live in a suburb, a safe community. The mother survived that terrible night. My daughter told me the story; she was in high school at the time. All of this his happened to her best friend’s mother. Is she all right? I asked. My daughter wasn’t sure. Margie’s mother was in the hospital because she’d been assaulted. My daughter was trying to figure out what that meant—assaulted. I stared at her. I realized I’d never told her, never talked to her about any of this danger, because if I said the words, their meanings might come close to her, might become real.

Silence in the poetry community:

Some years ago, my first book came out and I was doing a reading at a poetry center. An important poet attended, the head of an MFA program. I was pleased, wanted to belong to some invisible cohort which she represented in my mind, wanted to matter. She stayed by the doorway as people filed out of the room and our eye met. Why’s it so heavy? she said. A species of complaint, oh no, my heart slumped down. I shrugged, Yeah, well, I’m trying to lighten up. That was my answer, but should I?

Silence in LA during the crack epidemic:

In those days my default option on any situation potentially involving a gun was: turn your back. If you want to shoot me, shoot me in the back. Somebody taught me that lesson in my late teens; his name was Big Hazard. And what kind of person learns a lesson like that— well, I can tell you—someone shut down, terrified, and completely enraged. Someone who does not have full access to her mind—so much of it censored material, fully banned.

When I taught third grade in South Central, everybody was frightened and everybody was angry. The community was being torn apart. I blamed gangs, blamed my principal, blamed the police, blamed the community. One evening, a whole group of young men had gathered on the playground. They shouted out what I took to be catcalls as I left my classroom. I turned my back. Walked across the asphalt headed for the parking lot, tap tap of my little pumps, my own horror movie trope, tap tap. I was scared and defiantly quiet. One of them threatened, Girl, you better talk, and straight out of my frightened angry back I telegraphed a fierce silent message, Who’s gonna make me? There was a beat of his silence and then he called out, I’m gonna make you talk. I hurried on, thinking, my god, we just had one crazy psychic exchange, didn’t we?

The next day at work, somebody taught me another lesson. A middle-aged Black woman in the course of a random conversation, said, You get into some kind of situation, it could be anywhere, it could be the grocery store, you don’t know the man, he could be crazy, you don’t know, you have to talk to him, you can’t let it go, sometimes you got to talk. I was nodding; wondering if the whole neighborhood was psychic. How does everybody else know how to communicate, why am I so mute?

My point is how does silence help or harm us? Sometimes you got to talk. I had to learn that. I thought silence and anger might be the best way to work with shame and fear. But I was wrong. Why not propitiate a different god, try a different magic? Try speech, try god-given powers of the tongue. Try the ameliorating force of human exchange, the liberation of knowledge. Try writing down words, writing books. Someone might read them. Sometimes you got to talk. It doesn’t matter why it’s so heavy; doesn’t matter why you can or can’t be happy.

Let’s figure out who’s banning the books in our heads. Let’s figure out taboo, let’s figure out mercy. Let’s figure out kindness, starting over every morning. Our loft conversions, our suburbs don’t protect us. Banning books doesn’t save children, censoring our thoughts and feelings, our experience, our past, won’t make us acceptable, or help our art. Our shiny shoes from Macy’s don’t protect us. And neither do our degrees, our salaries, our aspirations. We’ve got to listen into the silence, listen to the words, do our best to understand what the speaker needs to say. We’ve got to speak up and write down and respect the stories inside us.

Was it Beautiful?

Here is a subdivision west of Van Nuys airport.

Here is the spindle I hang from, this world, this head of grain.

Here is a little dot on something so small

but tectonic in origin.

Here are my papers. Here is the world

with hepatitis C and a shadow not unlike a cancer scare.

Here is chicken in a paper bag,

shiny hair falling out of a barrette.

Here is the world with oatmeal in its beard

and smoke on its breath.

Was it beautiful? My world?

The kids on my block played T-ball and Tetris

one accidentally shot a boy in the desert.

We did a good job staying unsentimental.

Was it beautiful? Was it instinct? Commerce?

It was the world.

Here is that holy bone

that connects spine to pelvis.

Here is Eagle Rock. Fireweed

on the side of the freeway. A cul-de-sac guardrail.

The earthquake of ‘94. We painted our faces

by lantern light, washed in the hot water heater.

Here is the LAPD, the Rodney King riots.

Here is a crunch of dirty ice, some stolen steaks—

you can buy ‘em or not, says the world.

Still, I remake it over and over again.

Here is a six-bed crisis facility, a titanium heart valve,

a castle built out of popsicle sticks.

By Kim Young

This poem came into being in response to the question Why can’t you ever write a happy poem? It is included in Kim’s book, Night Radio, which won the 2011 Agha Shadhid Ali Prize in Poetry (The University of Utah Press). Night Radio was a finalist for the Tufts Discovery Award. It deals with the kidnapping and sexual assault of a young girl, and the resulting trauma for her and her family.

Marsha de la O.

Marsha de la O was born and raised in Southern California. Both sides of her family arrived in the Los Angeles area before William Mulholland built the aqueduct that brought in water from the eastern Sierras. De la O worked as a bilingual teacher in Los Angeles and the rural community of Santa Paula for more than twenty-five years. She holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from Vermont College. Her first book, BLACK HOPE, was awarded the New Issues Press Poetry Prize. She lives in Ventura, California, with her husband, poet and editor Phil Taggart. Together, they produce poetry readings and events in Ventura County and are also the editors and publishers of the literary journal Askew.

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Kenley Conrad: An Open Letter to People who like to Ban Books

Attention people who like to ban books! Have you ever seen a teenager reading a copy of CATCHER IN THE RYE and thought, “I don’t like this and therefore no one else should either”? Have you ever woken up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat after having nightmares of children reading THE SCARLET LETTER? Are you on a first-name basis with the school board president because you’ve called so often to complain about local youths reading THE GRAPES OF WRATH? Do you have copies of FAHRENHEIT 451 stacked next to your fireplace in lieu of firewood? If you answered yes to any of those, then this letter is for you!

Simon & Schuster, Reprint Edition, January 2012.

I would like to invite you (yes you!) to ban my book. Yes, you read that right. Please ban my book. Ban the ever-living crap out of it. I would like it if you would print out leaflets announcing the ban on my book. Please make sure you include a ranting diatribe against the apparent sins of my writing. Hand the leaflet to everyone in your town or local high school. Send the leaflet to Mars for the Martians so they can be warned against the offensive sixty-thousand word novel that offended your eyes and sensitive mind. Please host a bonfire and roast s’mores over the smoldering remains of my book. You may be asking why I would want you to do these things. I’ll tell you.

Because I hope that while you are gleefully throwing paperback copies of my latest work into the flames there is a young girl who is overcome with curiosity about the book adults hate so much. I hope that she snatches a book from the fire and presses it against her chest and runs home with it while the dying embers singe her skin. I hope that she stays up late and reads this book under the covers. I hope that she’s introduced to stories and ideas she’s never known about and that it opens her up to passion and dreams she’s never known before. I hope that by banning my book, you push people closer to it.

Swoon Romance, September 2014.

When I was a teenager I was also drawn to the forbidden and the banned. When my parents said that I couldn’t read HARRY POTTER I responded by borrowing the books from a friend and reading them with a flashlight in the secret of the night. Silently and alone, I cried my eyes out during the whole seventh book in that exquisite kind of heartbreak that is purely exclusive to books.

It is time to face facts: banning books doesn’t work. Sure, you may keep the books off of school reading lists and out of public libraries, but you alert young readers to a book they may have otherwise ignored. You pique their interest. By banning books you encourage people to read them anyway. People will never stop buying and never stop reading banned books.

So that brings me back to my original point. Will all of you book banning folks out there please dig down deep into the shadowy depths of your black heart and do me a favor by banning my book? I’d really like to be a New York Times bestselling author and if you ban my book I’ll be one step closer to reaching my dreams.

XOXO,

Kenley

Kenley Conrad.

Kenley Conrad is the YA author of the Holly Hart series. Her book HOLLY HEARTS HOLLYWOOD is currently available on Amazon. Its sequel HOLLY HEARTS HEADLINES is available for pre-order. Kenley lives in Phoenix, Arizona and is constantly amazed that she hasn’t yet burst into flames from the heat. She has two cats and she has also been listening to the same Stephen King audiobook for a year. She enjoys binge watching Netflix with her boyfriend and taking long walks through to the refrigerator.

September 5, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Brenna Ehrlich: Pushing It

“Her book has a lot of sex in it,” my rock ‘n’ roll dude friend (who would probably laugh at being called a “rock ‘n’ roll dude friend”) told his buddy as we sat in the audience of a late-night comedy show in Los Angeles last weekend. “And a lot of ‘fucks,’” he added. We then settled in for a night of jokes about sex, drugs and whatever.

All Ages Press, August 2015.

At first, I was pretty shocked that my friend – who has written some pretty dark songs, including one about a woman who murders her children and makes confetti out of their flesh – was shocked by my book.

There’s no actual sex in it (as in, no one, like, does it). Sure, yeah, there’s a TON of swears – I just searched and the word “fuck” crops up 171 times. I’m not exaggerating. 171. But, I mean, that’s what being a teenager entails: thinking about sex a lot (and for some of us, that’s it) and, when you learn to swear, abusing that ability as much as possible. And, yes, my book gets a little extreme (no spoilers) but that’s what fiction is: a heightened version of real life – a chance for readers to go beyond who they are and where they live and what they do and grow – at least by proxy.

And that’s why we need YA literature that pushes it – we need books that both capture teenage experience and go BEYOND teenage experience. Because that’s what growing up is.

I understand my friend’s confusion. He’s an adult. He probably hasn’t picked up a book characterized as “YA” since he was actually a YA (and back then that genre didn’t even exist). He went into my book expecting a novel for kids – and we as adults often forget what it was like to actually be one. A teenager, that is. Most of us picture innocent pimpled masses screaming for Justin Bieber when the word “teen” is uttered. Pimpled masses that must needs be protected from the “real world” at all costs.

(Sidenote: On my Goodreads page the only ones bothered by the “fucks” are the adults – the teens don’t even mention them.)

Ember, Reprint Edition, August 2007.

One only has to look at the list of most-frequently banned books to get a sense of how much we fear the supposed corruption of children: on that list is HARRY POTTER (fear of devil worship and potentially homosexual undertones?), Robert Cormier’s THE CHOCOLATE WAR (fear of the dark side of human nature?), Stephen Chbosky’s THE PERKS OF BEING A WALLFLOWER (fear of teen angst and whatnot?), Annette Curtis Klause’s BLOOD AND CHOCOLATE (fear of werewolf sex?).

Dude, most of the books on this list are young adult fiction, and most are banned because someone somewhere doesn’t want children to be exposed to something for which they are not deemed ready.

What we forget, however, is how much we were ready for when we were teenagers – or how much we were ready, at least, to understand.

Sure, we were naïve. Or at least I was – but I’m guessing a lot of you were, too. We were a strange mixture of wise and naïve that we’ll never be again. When I was writing PLACID GIRL, I went back and read every single one of my teen journals. I was a particularly sheltered kid, to be honest – I didn’t drink, smoke, sneak out, have boyfriends or basically anything that my characters do. Still, the pages of my journals are riddled with “fucks,” exclamations of torment and a whole hell of a lot of anger and confusion.

Most striking, to me, were two passages from when I was 17: There’s a scrawled quote from a boy I liked (“Most people are really blunt and come to conclusions that aren’t based on anything. I don’t think you’re like that”) and a long, rambling entry right after we went to war praying ardently that no one die. Adult me initially read these pages as hopelessly naïve: “Ha, I still believed in love and whatever. Dudes are all awful. And, wow, kid, the whole thing with the war gets A LOT WORSE – just you wait and see.”

Atheneum Books For Young Readers, Reprint Edition, April 2014.

Then adult me took a step backwards and felt a little sad because, wow, teen me FELT things. Teen me hadn’t put up emotional walls and learned what was rationally worth getting upset about. Teen me got upset. Teen me fell in love. Teen me had naïve hope. And teen me, despite being hopelessly naïve, also read about the world beyond her small experience – she read THE CATCHER IN THE RYE (BANNED). She read WE ALL FALL DOWN (BANNED). She read TIGER EYES (BANNED). She wasn’t undone by those books – if anything, reality was much more frightening, and reading helped her make sense of it.

She could take Holden’s mental unraveling, because she understood it – it didn’t impel her to come undone herself, it made her feel less alone. She could take all the violence and horror in Cormier’s books, because she was starting to witness similar situations in real life – like when her grade school teacher was found dead at the bottom of her stairs. The books didn’t make her violent, they allowed her to process and work through it when good people she knew died. She could take the sexual nature of TIGER EYES. She didn’t go out and have sex herself, but she started to feel less uncomfortable thinking about it. And, I think, she could take PLACID GIRL – despite, or maybe because of, all the sex and swearing.

Brenna Ehrlich.

Brenna Ehrlich is a senior writer and editor for MTV. She co-wrote the book, STUFF HIPSTERS HATE, which is also a blog. She has written for Mashable.com, Esquire, Missbehave, Mental Floss, Radar and Heeb.com.

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Vanessa Barger: On Taking Away Books

Ah, banned books. This is one of those things that I love to discuss with people.

Random House Children’s Books, 2005.

Censorship and banning books are hotly debated topics for good reason. I will always be grateful that I had parents who believed they’d taught me well and respected me and my intelligence enough to hand me a book and then discuss it with me if I had questions. On the top 100 challenged book list from 1990-1999 (Found on the ALA’s website) there are a lot of books I read. Some of which my mom handed me.

I think sometimes that banning a book has an opposite reaction from what people think. While there are a certain number of people who will look at the list and write those titles down, never to read them, there is a bigger number of people who will go out and read the book because it’s been banned. To see what’s so awful, or to get the secret thrill of reading something that’s dangerous or bad.

Laurel Leaf, April 1994.

I’m NOT arguing that banning books is a good thing, mind you. I think that telling people what they can and cannot read is wrong. Especially kids and teenagers. They can handle a whole lot more than we give them credit for. They deal every day with more than we can imagine. That kid who’s sleeping in school and ticking off his teacher? His parents left two weeks ago and he doesn’t know where they are, but he’s paying the bills to keep a roof over his head.

You’re going to tell that kid he’s not mature enough to read TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD or THE GIVER? Seriously? What about the one over there who just talked her best friend into seeing a counselor because she was cutting herself – she can’t handle reading A WRINKLE IN TIME?

Month9Books, October 2015.

Books are designed to make you feel. Angry, sad, funny, or scared – they are designed to help you see the world in a different way than you might on your own. Why is this ever a bad thing? They take you places you can’t get to on your own, and maybe even help people deal with issues and things in their lives they have no other way of coping with.

People look at the world through their own set of glasses (or goggles, whatever) and what they see is based on their own experiences and lifestyles. Just because one person believes Harry Potter is evil, doesn’t mean that everyone does.

Taking away someone’s chance to come to their own conclusion is wrong and borders on the criminal. No one has the right to decide what I read. Banning books is a stupid idea. No one knows what is best for a stranger. Let people decide for themselves.

Besides, banning a book is basically giving it a neon sign that says “ Read Me!”

Wait…. On second thought…

Vanessa Barger.

Vanessa Barger was born in West Virginia, and through several moves ended up spending the majority of her life in Virginia Beach, Virginia. She is a graduate of George Mason University and Old Dominion University, and has degrees in Graphic Design, a minor in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, and a Masters in Technology Education. She currently teaches engineering, practical physics, drafting and other technological things to high school students in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia. She is a member of the SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators), the Virginia Writer’s Club, and the Hampton Roads Writers. When not writing or teaching, she’s a bookaholic, movie fanatic, and loves to travel. She is married to a fabulous man, and has one cat, who believes Vanessa lives only to open cat food cans, and can often be found baking when she should be editing.

A WHISPERED DARKNESS, a YA horror, released in August 2014, and SUPER FREAK, an MG Fantasy comes out October 2015.

Banned Books Guest Post from Vanessa Barger: On Taking Away Books

Ah, banned books. This is one of those things that I love to discuss with people.

Random House Children’s Books, 2005.

Censorship and banning books are hotly debated topics for good reason. I will always be grateful that I had parents who believed they’d taught me well and respected me and my intelligence enough to hand me a book and then discuss it with me if I had questions. On the top 100 challenged book list from 1990-1999 (Found on the ALA’s website) there are a lot of books I read. Some of which my mom handed me.

I think sometimes that banning a book has an opposite reaction from what people think. While there are a certain number of people who will look at the list and write those titles down, never to read them, there is a bigger number of people who will go out and read the book because it’s been banned. To see what’s so awful, or to get the secret thrill of reading something that’s dangerous or bad.

Laurel Leaf, April 1994.

I’m NOT arguing that banning books is a good thing, mind you. I think that telling people what they can and cannot read is wrong. Especially kids and teenagers. They can handle a whole lot more than we give them credit for. They deal every day with more than we can imagine. That kid who’s sleeping in school and ticking off his teacher? His parents left two weeks ago and he doesn’t know where they are, but he’s paying the bills to keep a roof over his head.

You’re going to tell that kid he’s not mature enough to read TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD or THE GIVER? Seriously? What about the one over there who just talked her best friend into seeing a counselor because she was cutting herself – she can’t handle reading A WRINKLE IN TIME?

Month9Books, October 2015.

Books are designed to make you feel. Angry, sad, funny, or scared – they are designed to help you see the world in a different way than you might on your own. Why is this ever a bad thing? They take you places you can’t get to on your own, and maybe even help people deal with issues and things in their lives they have no other way of coping with.

People look at the world through their own set of glasses (or goggles, whatever) and what they see is based on their own experiences and lifestyles. Just because one person believes Harry Potter is evil, doesn’t mean that everyone does.

Taking away someone’s chance to come to their own conclusion is wrong and borders on the criminal. No one has the right to decide what I read. Banning books is a stupid idea. No one knows what is best for a stranger. Let people decide for themselves.

Besides, banning a book is basically giving it a neon sign that says “ Read Me!”

Wait…. On second thought…

Vanessa Barger.

Vanessa Barger was born in West Virginia, and through several moves ended up spending the majority of her life in Virginia Beach, Virginia. She is a graduate of George Mason University and Old Dominion University, and has degrees in Graphic Design, a minor in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, and a Masters in Technology Education. She currently teaches engineering, practical physics, drafting and other technological things to high school students in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia. She is a member of the SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators), the Virginia Writer’s Club, and the Hampton Roads Writers. When not writing or teaching, she’s a bookaholic, movie fanatic, and loves to travel. She is married to a fabulous man, and has one cat, who believes Vanessa lives only to open cat food cans, and can often be found baking when she should be editing.

A WHISPERED DARKNESS, a YA horror, released in August 2014, and SUPER FREAK, an MG Fantasy comes out October 2015.

September 4, 2015

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Martina Boone: On Banned Books and the Spread of Ideas

Freedom is the reason I came to the United States with my family. In the Czech Republic, where I was born, communism and oversight by the pro-Soviet regime meant that freedoms were limited. My parents decided to escape, leaving behind their family, friends, savings, and comfortable lifestyles for the sake of hope and the freedom to work and speak and think as they liked. I was along for the ride, but I grew up with the knowledge of their sacrifice, and it shaped who I am.

Freedom is a powerful motivator.

Simon Pulse, October 2014.

In Czechoslovakia, there had always been a deep love of literature. But under the thumb of the Soviet union, books were banned and heavily censored. You read what you were allowed to read, watched only select television programs, heard only selected radio stations, and got only the news that the government wanted you to know. It is no coincidence that the first president of a free Czech Republic was a poet and playwright who had spent years in prison for his dissident views and writings against the communist regime.

In the United States, I get to read any book I want. Any. Book. I am free to read what is important to me. I am free to choose.

The sum total of my thoughts and choices become who I am. I think as I read. I think because I read.

Books make me walk in the shoes of people I would never get to know in real life. Reading gives me perspective and empathy, and allows me to stretch and grow, to test my views and solidify my opinions. Becoming a writer is simply an extension of being a reader. For me, one follows the other as naturally as a tail follows a dog, but I can’t envision it working well the other way around. One does not write and then become a reader.

Most importantly, one does not develop new throughs, new ideas, new inventions, new break-throughs in a vacuum. Or through sound-bites or dip-the-toe-in candy-coated information. For any family, society, or nation to grow and thrive, they have to invest and nurture the seeds of new ideas. They have to allow people to discard ideas that don’t resonate with them.

Every time I hear about a book that someone wants to ban, I shake my head. It’s a concept I can’t wrap my head around. Not only because it’s a shame or doesn’t make sense, but also because here in the United States, banning books doesn’t work.

Simon Pulse, October 2015.

Shouting ideas down, banning them, twisting them, surpassing them, doesn’t stop them from existing. It only creates an echo-chamber in which we breed resentment and fanaticism.

But shouting ideas at people doesn’t help them to take root either.

Ideas grow best when whispered, when they are used to invite, to encourage, to reveal. They proliferate and thrive when they are allowed to be changed and embraced and recreated in the image of each individual who touches them.

Ideas are like books. No two people will have the same idea in the same way, and no two people read a book in the same way.

Some people will put more into a book than is there. Some will miss the point entirely. Some will fall in love with an aspect of a book that others hate, or vice versa. That’s the beauty of having freedom of thought.

So in celebration of Banned Books Week, I say let the haters hate. The more they shout about a book they want to ban, the more I want to go out and read that book. I’ve been like that since I was a teenager, and I know a LOT of teenagers who won’t pick up something someone tells them to read, and will run to the nearest bookstore or library to pick up something someone tells them they shouldn’t touch.

Want to make sure your kid reads a book you hate? Go ahead. Ban it. I dare you.

Martina Boone.

Martina Boone spoke several languages before she learned English after moving to the U.S. She has never fallen out of love with words, fairy tale settings, or characters who have to find themselves. She is the author of COMPULSION, the acclaimed first book in the Heirs of Watson Island trilogy, with PERSUASION releasing 10/27/15. She is also the founder of AdventuresInYAPublishing.com, a Writer’s Digest 101 Best Websites for Writers site, the CompulsionForReading.com book drive campaign for underfunded schools and libraries, and YASeriesInsiders.com, a site devoted to the discovery and celebration of young adult literature and encouraging literacy through YA series. Locally in her home state, she is on the board of the Literacy Council of Northern Virginia, helping to promote literacy and adult education initiatives.