Banned Books Month from Marsha de la O: Three Stories of Silence

First, a question for you: Has anyone ever said, Why can’t you write a happy poem? Has anyone ever said, Now what kind of crazy depressing shit are you putting out there?

You could say banning books is a prayer to the gods of silence. You could say silence is enacted as propitiatory magic. Some books are banned before they’re written.

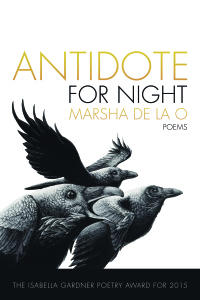

BOA Editions, September 2015.

Silence in my community and in my home:

Once a terrible crime happened in my neighborhood: a home-invasion robbery which became a kidnapping, the mother taken away in the middle of the night by an armed intruder. Our newspaper did not report it because it was too terrible. Also, because it was disjunctive; we live in a suburb, a safe community. The mother survived that terrible night. My daughter told me the story; she was in high school at the time. All of this his happened to her best friend’s mother. Is she all right? I asked. My daughter wasn’t sure. Margie’s mother was in the hospital because she’d been assaulted. My daughter was trying to figure out what that meant—assaulted. I stared at her. I realized I’d never told her, never talked to her about any of this danger, because if I said the words, their meanings might come close to her, might become real.

Silence in the poetry community:

Some years ago, my first book came out and I was doing a reading at a poetry center. An important poet attended, the head of an MFA program. I was pleased, wanted to belong to some invisible cohort which she represented in my mind, wanted to matter. She stayed by the doorway as people filed out of the room and our eye met. Why’s it so heavy? she said. A species of complaint, oh no, my heart slumped down. I shrugged, Yeah, well, I’m trying to lighten up. That was my answer, but should I?

Silence in LA during the crack epidemic:

In those days my default option on any situation potentially involving a gun was: turn your back. If you want to shoot me, shoot me in the back. Somebody taught me that lesson in my late teens; his name was Big Hazard. And what kind of person learns a lesson like that— well, I can tell you—someone shut down, terrified, and completely enraged. Someone who does not have full access to her mind—so much of it censored material, fully banned.

When I taught third grade in South Central, everybody was frightened and everybody was angry. The community was being torn apart. I blamed gangs, blamed my principal, blamed the police, blamed the community. One evening, a whole group of young men had gathered on the playground. They shouted out what I took to be catcalls as I left my classroom. I turned my back. Walked across the asphalt headed for the parking lot, tap tap of my little pumps, my own horror movie trope, tap tap. I was scared and defiantly quiet. One of them threatened, Girl, you better talk, and straight out of my frightened angry back I telegraphed a fierce silent message, Who’s gonna make me? There was a beat of his silence and then he called out, I’m gonna make you talk. I hurried on, thinking, my god, we just had one crazy psychic exchange, didn’t we?

The next day at work, somebody taught me another lesson. A middle-aged Black woman in the course of a random conversation, said, You get into some kind of situation, it could be anywhere, it could be the grocery store, you don’t know the man, he could be crazy, you don’t know, you have to talk to him, you can’t let it go, sometimes you got to talk. I was nodding; wondering if the whole neighborhood was psychic. How does everybody else know how to communicate, why am I so mute?

My point is how does silence help or harm us? Sometimes you got to talk. I had to learn that. I thought silence and anger might be the best way to work with shame and fear. But I was wrong. Why not propitiate a different god, try a different magic? Try speech, try god-given powers of the tongue. Try the ameliorating force of human exchange, the liberation of knowledge. Try writing down words, writing books. Someone might read them. Sometimes you got to talk. It doesn’t matter why it’s so heavy; doesn’t matter why you can or can’t be happy.

Let’s figure out who’s banning the books in our heads. Let’s figure out taboo, let’s figure out mercy. Let’s figure out kindness, starting over every morning. Our loft conversions, our suburbs don’t protect us. Banning books doesn’t save children, censoring our thoughts and feelings, our experience, our past, won’t make us acceptable, or help our art. Our shiny shoes from Macy’s don’t protect us. And neither do our degrees, our salaries, our aspirations. We’ve got to listen into the silence, listen to the words, do our best to understand what the speaker needs to say. We’ve got to speak up and write down and respect the stories inside us.

Was it Beautiful?

Here is a subdivision west of Van Nuys airport.

Here is the spindle I hang from, this world, this head of grain.

Here is a little dot on something so small

but tectonic in origin.

Here are my papers. Here is the world

with hepatitis C and a shadow not unlike a cancer scare.

Here is chicken in a paper bag,

shiny hair falling out of a barrette.

Here is the world with oatmeal in its beard

and smoke on its breath.

Was it beautiful? My world?

The kids on my block played T-ball and Tetris

one accidentally shot a boy in the desert.

We did a good job staying unsentimental.

Was it beautiful? Was it instinct? Commerce?

It was the world.

Here is that holy bone

that connects spine to pelvis.

Here is Eagle Rock. Fireweed

on the side of the freeway. A cul-de-sac guardrail.

The earthquake of ‘94. We painted our faces

by lantern light, washed in the hot water heater.

Here is the LAPD, the Rodney King riots.

Here is a crunch of dirty ice, some stolen steaks—

you can buy ‘em or not, says the world.

Still, I remake it over and over again.

Here is a six-bed crisis facility, a titanium heart valve,

a castle built out of popsicle sticks.

By Kim Young

This poem came into being in response to the question Why can’t you ever write a happy poem? It is included in Kim’s book, Night Radio, which won the 2011 Agha Shadhid Ali Prize in Poetry (The University of Utah Press). Night Radio was a finalist for the Tufts Discovery Award. It deals with the kidnapping and sexual assault of a young girl, and the resulting trauma for her and her family.

Marsha de la O.

Marsha de la O was born and raised in Southern California. Both sides of her family arrived in the Los Angeles area before William Mulholland built the aqueduct that brought in water from the eastern Sierras. De la O worked as a bilingual teacher in Los Angeles and the rural community of Santa Paula for more than twenty-five years. She holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from Vermont College. Her first book, BLACK HOPE, was awarded the New Issues Press Poetry Prize. She lives in Ventura, California, with her husband, poet and editor Phil Taggart. Together, they produce poetry readings and events in Ventura County and are also the editors and publishers of the literary journal Askew.