E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 33

September 7, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Bennett Madison: Other Sides of Censorship

I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who would admit they want to ban books. I know these people are out there, but I think we travel in different circles. Book banning has a bad reputation these days. You don’t meet many writers who are into it.

Grand Theft Auto: Vice City.

But censorship is rarely as straightforward as we think of it as, and I’m always surprised when a mom-friend talks mentions wanting to ban Grand Theft Auto, or when the community I’m part of decides to boycott an author because we think he’s an asshole. Or every time I’m on a panel at which people in the audience bring up the idea of putting warning labels on YA books– there’s always one mom who wants to talk about warning labels!– and the nervous reaction of other authors is often, well, uh… I mean, I guess it might not hurt?

None of those things are censorship, exactly. But every time something like this happens, it’s a a reminder that even those of us who would fight tooth and nail for Judy Blume’s right to be in the library might not always be as different from book banners as we imagine ourselves.

Not long ago, there was an internet furor over the Kickstarter campaign for a book called ABOVE THE GAME, which many people said sounded a lot like a manual for sexual assault. It eventually got defunded and taken off the site because of outrage and various petitions. Awhile before that, a self-published book (a book that– let’s face it– had probably sold about two copies ever) was challenged by an internet mob and successfully removed from Amazon because of the sympathetic way it presented pedophilia.

I bring up these cases not to argue that the efforts to remove the books were wrongheaded or because those efforts constituted book banning. Asking a corporate website to remove a book isn’t the same as burning it, right? Anyway, these books did sound outrageous. They sounded like they could maybe even harm people.

Then again, people have said that my books are outrageously offensive, and that they could harm people. A few people have actually suggested burning my books. Their reasons for saying these things are often reasons to which I’m politically sympathetic– reasons I might even agree with, if I hadn’t read the books to know the content they were referring to.

We think of book banners as those other people. We think of them as prudes, as people we have nothing in common with. They’re those crazy people who think HARRY POTTER endorses witchcraft.

Puffin Classics Paperback Edition, March 2008

But while plenty of books are challenged for reasons I completely disagree with– because they’re too frank about sex, or because they present gay characters in a sympathetic light, or whatever — some of the most frequently banned book are those like HUCKLEBERRY FINN and TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD and BELOVED, all of which have people have objected to because of concerns that they’re racist.

Well, racism is bad, right? And so is homophobia; so is misogyny. I agree I wouldn’t want my kid reading a super racist book in school. Would you?

The problem,of course, that fiction is slippery and complicated and weird, and what I think of as one of the most classic books of all time could be, to you, just another book that uses the N word.

Look, the idea that HUCKLEBERRY FINN is racist because it uses slurs is clearly ridiculous, but look: If my (imaginary) kid came home from school carrying one of James Dobson’s books, or LEFT BEHIND, or IT HAPPENED TO NANCY or, hell, even one of Orson Scott Card’s nastier pieces of work, I’m not sure I wouldn’t raise a stink about it. (Never mind the fact that I actually read and loved all of Orson Scott Card’s work growing up, and never even noticed the homophobia in his HOMECOMING saga.)

What would that make me, then?

None of this to say that we shouldn’t speak out against books that offend us to our core. But I do think it’s important to be thoughtful about the ways that we try to silence work that we don’t like; about how we participate in a culture of censorship even if we’re not going out and burning books in the town square.

I think it’s important to ask ourselves: what books are as dangerous as yelling fire in a crowded theater? What speech do we draw the line at? What’s censorship, and what’s just voicing an opinion? What’s so offensive that it should get boycotted?

What are we really afraid of?

Bennett Madison.

Bennett Madison is the author of several books for young people including the LULU DARK mysteries, THE BLONDE OF THE JOKE and SEPTEMBER GIRLS (HarperTeen, 2013), which received starred reviews from Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, School Library Journal, Booklist and the Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books. He attended Sarah Lawrence College and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

September 6, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Robyn Bavati: The Author Wasn’t Meant to Know

My first novel, DANCING IN THE DARK, is the story of a girl whose passion for dance conflicts with her family and her faith. Raised in a haredi (ultra-orthodox) Jewish home, she ultimately rejects an orthodox lifestyle in order to pursue a career as a dancer.

Flux, February 2013.

A few months after the book was published, the librarian at Mount Scopus College asked me to come to the school during Book Week to discuss the novel with the Year 9 students. I was delighted by the invitation and accepted with alacrity. Always glad of an opportunity to speak at a school, I was especially pleased to be invited to that one. Not only is Mount Scopus College the largest Jewish day school in Melbourne, it is also the school I went to for my entire twelve years of schooling, and one that all three of my children attended at one point in time.

Personal reasons aside, I felt that Mount Scopus students in particular (the vast majority of whom are from non-observant Jewish homes), would be fascinated by the haredi world my novel portrays. Although I did not write the book for a primarily Jewish readership, I felt that it would be of special interest to Jewish readers; it would be an eye-opener for the many students unaware of the insular lives led by some who share their heritage, and I hoped it would generate some interesting classroom discussion.

Several weeks after confirming the date with the librarian, the school principal –Rabbi James Kennard, a strictly orthodox rabbi – found out about my scheduled visit. He rang me to say that although he hadn’t read my book, he had “some concerns”. He asked if he could come to my house one evening to discuss them, and despite never having met him, I agreed.

He still hadn’t read the book by the time he came to discuss it the following week. Even so, he said that while he was looking forward to welcoming me at the college, he had a problem promoting my book at the school because he understood that its “anti-religious” content was “antithetical to the school’s modern-Orthodox ethos”.

I explained that the book is not anti-religious at all, but anti-coercion, pro-choice and pro-tolerance. It doesn’t vilify religious people; nor does it incite hatred towards religion or anyone choosing to live a religious lifestyle.

“Is it true,” he asked, “ that the book is about a girl who breaks the laws of Shabbat in order to dance and that this is treated sympathetically?” I agreed that it was, and he said that in that case he did not wish to promote it at the school since it did not represent the values and principles of Orthodox Judaism, according to which the Orthodox lifestyle is the only “right” way for Jews to live. He then asked me if I could come to the school to discuss my writing but not mention the book.

I said I didn’t think I could, and that if I were a parent at the school (which at one point I was), I’d be very upset to think that the school was employing that kind of censorship (to which he replied, “I don’t care what the parents think; my job is to uphold the policy of the school”). I suggested that if he didn’t agree with the viewpoint expressed in the novel, he should challenge rather than suppress it. (I might have added, had I thought of it at the time, that the school library is, fortunately, full of books that don’t “represent the values and principles of Orthodox Judaism”, and that this must be the case if the school is to produce students capable of broadminded, independent thinking.)

Rabbi Kennard said he would think about my suggestion and get back to me, and I gave him a copy of the book to read in the meantime. A week or so later, I received a phone call from the school librarian. (Interestingly, she is herself an orthodox Jew, and was keen on the students reading the book as she thought it presented a well-balanced view of religion and portrayed the Haredi community in a respectful, sympathetic and authentic manner.)

Having finally read the novel, the rabbi was even more disapproving of it and had suggested to the librarian, as he had to me, that I speak to the students about my writing but not refer to the book at all. Quite sensibly, she replied that the book was the reason she’d invited me to speak in the first place, and suggested instead a discussion between him and me, in front of the students, which she would facilitate. After several days of deliberation, the rabbi agreed to this, and the day of the scheduled discussion arrived.

Flux, August 2013.

The librarian greeted me somewhat apologetically, saying that normally when a guest writer is invited to the school, the students are prepared for the visit by their English teachers, who tell them something about the book, read an excerpt, discuss the key themes and ideas, and recommend they read it if possible before the author arrives, but in this instance Rabbi Kennard had forbidden any of the staff to mention the book, so the students were entirely unprepared, knowing only that a guest writer was coming.

I understood then that the rabbi wanted the students to hear his opinions before they had a chance to form their own. Even that didn’t bother me – I just hoped I could inspire them to read the novel.

The rabbi was vitriolic in his condemnation of the book, claiming that I had presented religion in a purely negative light, that all the religious characters in the book were nasty and objectionable, and that the book was full of “factual inaccuracies”.

I had in fact gone out of my way to show that while the religious lifestyle suited some, it did not suit others. Moreover, some of the kindest, more loyal characters in the book were extremely religious, while others were not.

When pressed for examples of “factual inaccuracies”, the rabbi said he did not personally know any haredi people like those I’d described. I said I didn’t think the term “factual inaccuracy” could be applied to the portrayal of a fictional character. He then mentioned other “inaccuracies”, like the fact that the real haredi school went up to Year 12, whereas my fictional school only went up to Year 11, and that many of the girls in the real haredi school took ballet classes after school hours, whereas in my fictional book this wasn’t allowed.

Quite apart from the fact that my book is fiction, for many years the real haredi school only went up to Year 10, and even the current Year 12 does not follow the state curriculum and does not provide students with the opportunity to obtain the certificates required for university entrance. Similarly, some haredi girls do take ballet because a Jewish dance teacher opened a girls-only Jewish dance school. However, if that school were to shut down tomorrow, those girls would no longer be taking ballet – they would not be permitted to take dance classes anywhere else, just as my own niece was not permitted to take ballet when she attended the actual haredi school on which my fictional one is loosely based.

I pointed out to the rabbi that while the school in my novel is not an exact replica of the one to which he was referring, the book does indeed give an authentic portrayal of a community whose members censor books, don’t watch TV or go to movies, and where there is a segregation between the sexes.

As the session ended, I told the students they had heard two very different viewpoints, and suggested they read the book and make up their own minds, and the rabbi concurred.

The students left, the rabbi thanked me for coming, and I was all set to leave, happy in the knowledge that while my novel would probably not be chosen as required reading and discussed at length, at least now, having heard the principal’s objections to it, the students would probably borrow it from the school library and form their own opinions.

But I had one more question for the librarian before I left. I wanted to know how the students had been responding to the book so far. Embarrassed, she admitted what she – and Rabbi Kennard – had not wanted to tell me – that although she had bought five copies for the library as soon as I agreed to visit the school, the rabbi had not allowed her to put the books on the shelves. However, now that he’d just agreed the students should read it and judge for themselves, she was hoping he’d changed his mind. She asked if I’d mind if he wrote a statement expressing his own view of the book to be placed at the front of each copy, and I said I wouldn’t. She said she’d talk to him again, and let me know. Unfortunately, she couldn’t persuade him, and the books have never made it onto the library’s shelves.

I wrote about the session at the college and about the censorship of my book on my blog, and the librarian rang me and said the principal wanted me to remove my post. I did not oblige him, and am astonished that he ever thought I would. I appreciate that he did not withdraw the invitation to the school once I’d been invited, though I suspect he had his own motives and was worried about the repercussions such an action might provoke.

DANCING IN THE DARK was written for teenagers. It is entirely age appropriate. It does not contain foul language, sex scenes or any offensive content. But it champions personal freedom and the idea that some things are more important than religion.

On the college website, Mount Scopus claims to “enable each student to make an informed choice as to the meaning of their Jewish identity” since it “supports and promotes the principles and practice of… freedom of religion, freedom of speech and association, the values of openness and tolerance…” I’m not sure how banning a book such as mine helps students make informed choices. I certainly don’t see how it is consistent with upholding freedom of speech. And surely freedom of religion encompasses both the right to be religious and the right not to be.

I’m amazed that the principal thought I’d collude in silencing my own voice, my own opinions.

Fortunately, not all school principals agree with Rabbi Kennard, and while my novel has been banned at the one Jewish school I wish would embrace it, it has made its way onto the curriculum at a number of Christian girls’ schools. The girls love it and say it inspires them.

Though most readers find DANCING IN THE DARK engaging, moving, and thought-provoking, others (a minority) think it subversive, disturbing and even immoral. But perhaps there is merit in a work that is perceived as threatening or influential enough to be banned.

When I think of other banned books – by such well-known and beloved writers as D.H. Lawrence and J.K. Rowling – I know I’m in good company. And while banning a book is the greatest insult, perhaps it is also a compliment.

To read a statement by Rabbi Kennard and comments by members of the local Jewish community on a very similar post, click on this link: http://galusaustralis.com/2010/11/3708/book-censorship-at-mount-scopus-college/

Robyn Bavati.

Robyn Bavati has taught creative dance in schools and worked as a shiatsu therapist. These days, she writes fiction for teens. Her debut novel, DANCING IN THE DARK first published in Australia in 2010, was released in North America in February 2013. Her second novel, PIROUETTE, will be out in November.

Like Robyn’s facebook author page or visit her website

September 5, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Ellen Hopkins: On the VMAs, Salacious Books, and Censorship

Here I am, right up against the deadline for this blog, and I’m happy to be here because two very recent events will influence what I have to say. The first has been all over the Internet for the past couple of days—Miley Cyrus’s infamous performance on the VMAs. The second, which at first glance may seem light-years away, was a discussion about books that popped up on my Facebook page today.

Miley Cyrus at the VMAs.

I’ll start with Miley, who has been desperately trying to escape her Disney persona for a number of years. Here’s a funny piece of backstory. A few years ago, the media was all over a picture of Miley carrying my novel IDENTICAL. Headlines screamed things like, “Miley Cyrus’s Favorite Filthy Book,” and at least one journalist was of the opinion that reading “salacious” books was Miley’s bid to free herself of Hannah Montana. Despite its subject matter, I don’t see IDENTICAL as salacious or filthy. But, wow. Maybe in some small way I was responsible for the VMAs debacle!

No, with or without R-rated books, Miley would doubtless still be trying to shed her adolescent skin in favor of adulthood. I wasn’t particularly offended by the performance. (Although I thought the dancing wasn’t particularly professional or entertaining. More like a lot of strutting and awkward kicking of legs.) As an adult, I’ve witnessed raunchier things. However, some younger viewers might watch someone they admire twerking and believe it’s a legitimate way to demonstrate their own sexuality, without a real understanding of what sexuality is. I will also point out, as others have, that there were choreographers and producers involved in creating Miley’s performance. Is that how they view a young woman’s coming of age? Because the message we received was “growing up” means rubbing up against somebody. Or some giant stuffed animal. Or something.

Margaret K. McElderry Books, September 2013.

This morning, another writer posed the question on Facebook, “What were you reading as a young teen that was inappropriate for your age?” Responses ranged from THE CLAN OF THE CAVE BEAR to PEYTON PLACE and VALLEY OF THE DOLLS, to my own answers: STORY OF O and FEAR OF FLYING. STORY OF O, if you are unfamiliar with it, was 1950s-era erotica about dominance and submission (waaaay before 50 SHADES made the subject mainstream), while FEAR OF FLYING is about a woman poet (!) looking for no-strings-attached sex. Both books were fairly graphic, at least for the time they were written. I confess I also read the others, including John Irving’s kinky offerings, plus books like THE GODFATHER and SOMETIMES A GREAT NATION, where sex was liberally presented, but not the main storyline.

These books presented many kinds of sex: committed; noncommittal; free; BDSM; bored; passionate; Bohemian; born of true love. Reading about sex and sexuality in all its varied forms allowed me a much broader perspective about its meaning than Miley’s performance, pornography, or even the cheesy erotica so prevalent today. By reading about people who felt real (rather than just as vehicles for titillation), sex felt real—not always good and sometimes way too good. But the words I read allowed me to create my own imagery. I wasn’t force-fed someone else’s.

I’m sure many of my friends’ parents would have totally freaked out if they’d thought their kids were indulging in similar reading material. (Some were, some weren’t.) But my mom never attempted to censor what I read. She understood books presented a safe way to explore adult experiences, including sex. If I needed guidance, she was there to give it, but I never asked for it, and I think I ended up okay. What I came away with from all that salacious reading was the importance of self-respect and not giving myself away too cheaply. The truth is, I never did.

I don’t understand why would-be censors are so afraid of books. Especially today, when all a young person has to do to find sex is turn on the TV or plug into a video game, where someone else’s idea of what’s sexy is presented, and in overtly visual ways that leave nothing to the imagination. Books offer perspective, and allow readers to draw their own imagery around the words on the page. Reading is safe, sane, and a lot less disturbing than watching a young woman shed her adolescence on live TV. Wonder whose idea the foam finger was. Not to mention the tongue.

Ellen Hopkins.

Ellen Hopkins is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of CRANK, BURNED, IMPULSE, GLASS, IDENTICAL, TRICKS, FALLOUT, PERFECT, TILT, and SMOKE, as well as the adult novels TRIANGLES and COLLATERAL. She lives with her family in Carson City, Nevada, where she has founded Ventana Sierra, a nonprofit youth housing and resource initiative. Visit her at EllenHopkins.com and on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter at @EllenHopkinsYA. For more information on Ventana Sierra, go to VentanaSierra.org.

September 4, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from David Lomax:

In twenty-three years of teaching English at the high-school level, I must admit that I’ve managed to get away with a lot. Students in my classes have read swear words, graphic depictions of violent and sexual acts, and been presented with characters whose values were radically different from their own. They have, of course, also been introduced to beautiful prose, vibrant characters, compelling plots and wide new vistas. In short, they have read literature.

Little, Brown and Company, Mass Market Edition, May 1991.

I believe that it is part of my job to try to turn my students on to the wonders of great fiction and to have them be life-long readers. However, great fiction is sometimes very controversial, so now and then (though not very often at all) the literature I bring to my students results in challenges. I’d like to offer an analysis of those challenges and some advice to teachers who may face them. In doing so, I will not shy away from controversy myself. In fact, I’ll start with my most controversial point.

People want to ban books because they don’t know how to read fiction (and religion is to blame).

I mean this quite sincerely. I’ll use Christianity as an example because I was brought up in that religion, but other religions would work just as well. The key Christian texts are the gospels, the sometimes widely divergent stories of the life, ministry and martyrdom of Jesus. In those texts, as well as performing miracles, Jesus tells a lot of stories. People in the parables, as the stories are called, invest their money poorly, complain about how others are remunerated for their labors, and arrive late to wedding feasts.

So far, so good, right? People then interpret these stories: we learn that we should use our talents to glorify the lord, be thankful for what we’re given, and take advantage of our opportunities to get into heaven.

Again, so far, so good.

The problem comes when people then generalize this kind of reading, a symbolic and moralistic reading, to all other fiction.

Because, let’s face it: Jesus’ parables are a form of fiction. When people get the impression in some churches (not all, by any means) that this is the way you read fiction, by looking for coded symbolic instruction on how to live your life and what you should believe – then those people are pretty poorly prepared to read most fiction.

More simply: The guy in the Jesus parable who builds his house on the rocks (as opposed to putting a foundation into sand) is directly symbolic of all of those people who live their lives according to the precepts Jesus sets out. Easy, right? Smart builder equals all people who listen to good advice. Incredibly stupid builders equal people who refuse to listen to good advice.

But try that form of reading with THE CATCHER IN THE RYE. What is the author saying, that we all ought to take off out of school, meet prostitutes, get beaten up, and call everybody out on being fakers in order to eventually get some therapy? Or what about THE HANDMAID’S TALE? The author features people identifying themselves as Christians who do some horribly despicable things. Does this mean she thinks that all Christian men want to enslave women in a future dystopic distortion of an Old Testament story?

Anchor Books, Paperback Edition, March 1998.

What I’m saying may sound silly, but look at attempts at book bannings, and you will see exactly this sort of reasoning. In my home of Toronto, a parent tried a few years ago to get THE HANDMAID’S TALE removed from his son’s grade 12 English class because he said it violated the school board’s policies of respect and tolerance. Pointing out the less-than-savoury things that characters do in the book – rape and violence – this father said, “The board is adamant about those policies, but then puts books like this in place.”

That’s right – he was attempting to read the book as a parable. Atwood features bad things happening in this book therefore anyone who advocates the reading of this book is suggesting that these bad things should happen or have happened.

This sort of thing is even more obvious when you look at some of the crazy HARRY POTTER bannings in the last ten years. In 2006 parents in Georgia wanted the books removed from school libraries because the series “promotes the Wicca religion.” And that’s just one example. Poor J.K. Rowling has been accused of supporting witchcraft all over the place, just as Alice Walker has of “advocating” homosexuality, Vladimir Nabokov of encouraging pedophilia, Stephen King of inciting murder, Mark Twain of normalizing racism, and Anne Frank of creating ethnic tension.

All because people insist on reading fiction as instruction – either entirely symbolic or entirely literal in nature.

The thing is, they’re a little bit right

Don’t tell them I said this, but sometimes the book banners have a point. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not with them in any way. But what we never admit – and by “we” I mean the people who want young people to read the books I’ve mentioned, and even more that I’m about to mention – is that some of the reading material we pick does indeed have themes that may be critical of the status quo.

Look at THE HANDMAID’S TALE for example. One of my favourite novels. Another controversy that often follows that one is over Atwood’s insistence that the novel is not science fiction. These days, she prefers the term “speculative fiction” for what she writes – serious examinations of possible futures, rather than stories about sentient squid and ray guns in outer space – but back in the eighties, I remember her saying that her novel wasn’t science fiction because everything in it had already happened. In other words, misogynist theocracies in which women had no rights and were subject to religiously justified arbitrary male control were not science fictional in nature. In other other words: the Iranian Revolution been co-opted by fundamentalism just five years before that book was published – you join the dots.

So my point is that it’s entirely reasonable to read THE HANDMAID’S TALE as a critique of misogynist religious dogma – and this makes a lot of religious dogmatics very uncomfortable.

Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, June 2005.

Personally, I like that. And I’ll go further, because I want to be clear about this: would-be book-banners who insist that people like me are trying to engage in subversive social engineering are sometimes totally right. Look at the controversy a few years ago over AND TANGO MAKES THREE, a kids’ book about the two male penguins at the Central Park Zoo in New York who adopted an abandoned egg. Parents in Missouri, Illinois and North Carolina who objected to this either in schools or libraries thought it promoted homosexuality – that’s nonsense, of course. You can’t, in that sense of the word, promote homosexuality any more than you can promote right-handedness or green eyes as a choice a person might want to make.

You can, however, promote tolerance, acceptance and understanding. Which is, I think, a pretty fair reading of why some teachers are interested in having kids read AND TANGO MAKES THREE. And let’s face it: People like me who want kids to read books like that really do want to promote those values, just as we may, through having young people encounter other great books, want to promote many other progressive values: acceptance of the beliefs of others; understanding of the struggles of people from other social classes or ethnic backgrounds; critical attitudes towards misogyny or racism.

So how do we defend books against banning?

Here’s the problem: If you’ve got the forces of book-banning in your community, often insisting on reading things in a very literal or completely symbolic manner and yet you do in fact want to have young people read controversial literature that may lead them to think critically about their own values – how do you do that? How do you avoid book-banning?

Once a book has been challenged, there are all kinds of steps that must be taken, and these differ between jurisdictions – so I can’t offer any solid advice on this. What I can offer, however, to any high school teacher who worries that this trouble may loom on the horizon are a few thoughts about how not to end up in a book-banning situation at all.

Trust the students. If I’m going to read a controversial book with my students, I begin by admitting right up front that there are aspects of this book that are sensitive in nature. I used to read Alice Walker’s THE COLOR PURPLE with my seniors. Before doing so, I would warn them that the book had been banned in some places. I asked them if they thought that at their age their parents should be determining their reading choices. I asked them if offensive language in a book was the same as offensive language in the school hallway, on the street or at their dinner table. By beginning a dialogue with the students, I was able to get them interested in the book before we even began, and by eliciting from them the opinions that they should be able to judge their own reading material and that they might be interested in controversy, I got them on my side right away.

Listen to the parents. My wife (who is also a high school English teacher) has dealt with more challenges to books than I have. I think it’s a gendered thing: we have both, for instance, read Sharon M. Draper’s excellent TEARS OF A TIGER with freshman classes. This hard-hitting novel deals with the trauma that follows the drinking and driving death of a popular high-school athlete. A mother called my wife to complain that her daughter was having trouble with the emotional content of the book, and had started talking about suicide. This was a clear case in which intervention was necessary – and one in which my wife was able to provide a lot of help – but it started out simply with a parent saying her daughter was not to read “that book” anymore. Everything else came out only because the teacher listened. (As an amusing side-note, my wife did explain to the mother, who started out staunchly against the novel, that our students often respond best to books with high emotional content. “We read ROMEO AND JULIET next year,” she said. “Oh!” said the mother. “I just love that play” — at which point my wife felt it necessary to remind her that it was, after all, a play about teenage suicide.)

Keep the book, keep the student. The best principal I ever worked with was a big fan of win-win situations. But by this, he didn’t always mean compromises. The first compromise that is often suggested when a parent objects to a book is that of the student reading a different book from the rest of the class. I never like this solution, and I tell the parents that I don’t think it’s for the best. The student is cut off from the rest of the class, now, removed from the group experience of working towards understanding. I’m still there for the student, but nobody else is. I would much rather have the student read the book but be free to write about the controversy, write about what’s challenging to personal or family values, write about what’s wrong with the book. Dissent is welcome in my classroom, I tell parents. Having their child read a different book is a way of silencing dissent, of shuffling it off to one side. I would much rather keep the book in my class, and keep the student’s dissenting voice audible.

So I think understanding and communication can fend off a lot of attempted book bannings. It’s wrong to think of all book-banners as equivalent to those who would teach creationism as science. Some of them just have to be taught how to read fiction.

What could be more fun than that?

David Lomax.

At age eight, David Lomax was transplanted to Canada from his native Scotland. The same year, his parents read him Tarzan of the Apes, and he decided to become a writer. He didn’t get all of the cool jobs his other writer friends did to make their biographies sound interesting such as train driver, elevator repairman, or insurance underwriter. He was, briefly, a waiter. But not a good one. He currently divides his time between four great passions – writing, reading, teaching high-school English, and his wonderful family.

His debut novel, BACKWARD GLASS comes out in October from Flux Books.

September 3, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Sophie Masson: Beware of Once Upon a Time — The Banning of Fairytales

Some years ago, I experienced first-hand what drives some people to demand that books be banned, and stories be censored, even if the works in question are classics, and even if the vast majority of readers love them and consider them to be completely harmless.

Random House Australia, September 2013.

I’d been running an all-day creative writing workshop for gifted kids aged from about 8 to 13, in a public library in Sydney (Australia). I was basing the workshop around well-known fairytales, from Cinderella to The Frog Prince, Beauty and the Beast to Snow White to Little Red Riding Hood. These were stories that had nurtured my own imagination and whose golden threads had found their way into my own books.

The students were wonderful, keen, engaged, lively and imaginative, and they were thoroughly enjoying the exercises I’d devised – creating new plot lines around minor characters, inventing new characters, drawing maps of once-upon-a-time places, imagining what it’d be like to have magic powers. The library had invited parents to come and listen to the workshop if they wanted to, and that’s when trouble struck.

A parent came in when the workshop had been running for about an hour, sat next to her child and looked at his work. I thought she’d be thrilled – he’d been creating some great stuff. Then she jumped up and said, No, no, no! We’re leaving.

Flabbergasted, I asked her what was the matter. Quivering with indignation, she said, We’re Christians and I object to your theme! You’ve been making them write about magic! About fairies and witches and shapeshifters! It’s escapist nonsense and we ban fairytales and all those kinds of stories at home.

I was so taken aback that all I could do was stare as she gathered up her reluctant and dejected son and marched triumphantly out.

Of course, afterwards I thought of all the things I could have said to her. That she had humiliated not only me but her poor son, who had been so enjoying himself. And exactly what did being a Christian have to do with objecting to stories that had been created in a much more deeply Christian time than now? (My own staunchly Catholic parents considered fairytales to be part of our birthright.) I wanted to say that banning the magic of fairytales from your life didn’t chase away monsters, it made them stronger, besides hollowing and greying the world. I wanted to shout, Don’t you realise that in fairytale there’s not only escapism and imagination, but consolation and great wisdom, built up over centuries? Fairytale makes us dream but it also anchors us strongly in the world. How can you want to take that away from your son?

But I was too flustered to say anything. Gathering up the scattered threads of the workshop, my students and I got on with it. The other kids had been bemused by this eruption of the impulse to ban something you don’t understand; but they soon forgot about it in the joy of creating. As to the librarian, she was mortified on my behalf but also a little worried – would the parent take her concerns further? The innocent enjoyment of the day had been spoiled.

It was a graphic example to me of just what power those who seek to ban books can have. In their blindness, they think they alone have the truth. They certainly do not appear to realise that other people have feelings and ideas on the matter. And because such behaviour is so contrary to the way most of us act towards each other, it is intimidating and all too often they get their way.

Random House Australia, October 2013.

But it was also an example of how ridiculous the book-banners often are – and how consistent, too. Fairytales have been a major thread in our culture for centuries. And for all those centuries, fairytales have periodically been subject to banning orders – from those like the parent at my workshop who think that imagining fairies will somehow chase away belief in God, to those who think that they teach the wrong lessons about gender or class; from those who, Gradgrind-like, think children should only have ‘facts, sir, facts!’, to those who think that turning the big bad wolf into a sensitive new age vegetarian is going to somehow protect kids from real-life nightmares. When fairytales were first written down by the likes of Perrault and Grimm, they were attacked for being fit only for uneducated ears. And these days, an untruth is dismissed as ‘a fairytale’, though fairytales actually contain more truth, and deeper truth at that, than most so-called ‘realism’.

For that is how powerful the stories themselves are. Snow White and Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood and all the enchanted, extraordinary cavalcade of characters in fairytale live deeply in the very heart of humanity. They are part of our culture, inextricably woven into the fabric of our dreams and imagination. That is why they are attacked, and why they are banned by those who live in fear of the imagination, in fear of allowing themselves to dream, to see the world from a different angle, to escape from the grey of habit into the gold of enchanted perception.

Tolkien once said, ‘only jailers fear escapees’. And only those who seek to jail the lifeblood of the human spirit, imagination, could seek to ban such beauty from their own lives – and worse, from that of others.

Sophie Masson.

Sophie Masson was born in Indonesia of French parents and was brought up mainly in Australia. A bilingual French and English speaker, she has a master’s degree in French and English literature. Sophie is the prolific author of numerous young adult fantasy novels as well as several adult novels. She lives in Armidale, New South Wales, with her husband and children. Sophie’s most recent novels are SCARLET IN THE SNOW and MOONLIGHT AND ASHES, both based on fairytales.

September 2, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Dori Hillestad Butler: How Censorship Has Changed Me

I’m Dori Hillestad Butler and I’m the author of a banned book.

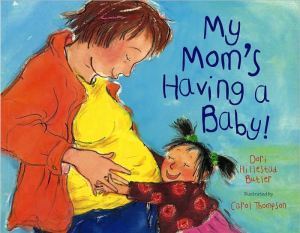

This book has been banned!

The book is MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY (Albert Whitman & Co., 2005). It received a starred review from Booklist, and was a Booklist Editor’s Choice Book for 2005 as well as a Top Ten Science-Technology award winning book.

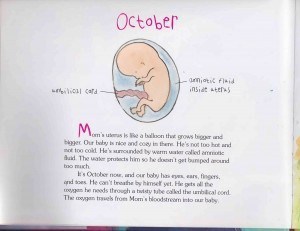

Let me tell you what it’s about in my own words rather than the words of people who don’t want you to read it. MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY is a story of a close-knit family’s joy and anticipation prior to the birth of a second child. It’s narrated by a girl named Elizabeth, who leads the reader through her mother’s pregnancy month by month and shares everything she learns about how that baby is growing inside her mother.

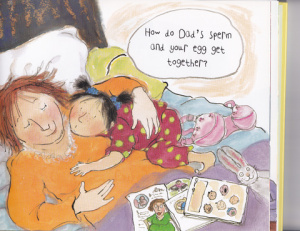

An interior illustration from MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY.

What’s so bad about that?

Elizabeth is one of those kids like, well… my own kids. She asks a lot of questions. She’s hungry for information. She wants to know how that baby got inside her mother in the first place.

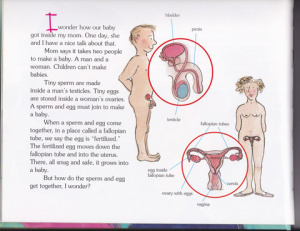

An interior illustration from MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY.

The above explanation doesn’t quite satisfy Elizabeth. She also wants to know:

An interior illustration from MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY.

And well…her mom answers her. Just like I did when I was pregnant with our second child and my four-year-old asked that question.

What do I have to say about that?

I know some parents would choose not to answer a question like “how do Dad’s sperm and your egg get together?” But that has never been my philosophy. I believe in giving children honest, accurate information, as much or as little as they want, whenever they ask for it. When it comes to questions about where babies come from, some children are satisfied with a simple one sentence response; others need more. In our house, if a child was mature enough to ask the question, he was mature enough to receive an answer. We wanted our kids to know that no matter what the question, they could always come to us, and we would take the question seriously and answer openly and honestly to the best of our ability. Yes, even if it was a question about S-E-X and even if it was asked at a very young age.

My husband and I are not the only ones who feel this way.

I wrote MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY for parents to read with their children, whenever the time is right. Talking about sex can be difficult. This book is meant to be a tool to help parents open dialogue with their children. You don’t have to read it all at once. If your child isn’t ready for some of the information contained within, by all means, skip those pages and come back to them when you and your child are ready. That’s why it’s a good idea to preview a book like this before offering it to your child.

But some people think this is a “bad” book and it doesn’t belong on library shelves. Many of them decided this without ever having read the whole book themselves. They “don’t need to read it” (some of them told me so in e-mails and in their Amazon reviews) because they know it’s “filth.” Some even described it as “pornography.” And because they’ve decided it’s not the sort of book they want their own children to read, they don’t want anyone else to have access to it, either.

Albert Whitman & Co., January 2005.

MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY has been challenged in Oregon, Indiana, Kansas, Colorado, Georgia, Nevada, Texas and Florida. Those are the challenges I know about; there could be others I don’t know about. It made the Canadian Library Association’s list of most challenged books and magazines for 2010, and was #4 on ALA’s list of most challenged books in 2011. In February of 2011, I faced a very public challenge to this book and appeared on Fox and Friends with the babysitter (yes, the babysitter, not the parent) who objected to the book. You can read all about that here: http://dorihbutler.livejournal.com/143156.html and here: http://dorihbutler.livejournal.com/143645.html

Some people believe libraries should be “safe” places to leave their children. They think their children should be able to wander around unattended, free to pick up any book in the entire library and know there’s nothing inside that book that they, as parents, would object to. Well, guess what? A library has a responsibility to serve the needs of an entire community, not just one family. A book that one parent doesn’t want her child to see might be the exact book another parent is looking for.

I would be lying if I said I said I never expected MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY to be challenged. You can’t publish a children’s book that deals with the facts of life in this country and not expect someone to object somewhere. But I never expected to face such a public challenge. I never expected to make ALA’s list of most challenged books. I never expected strangers to see a 3-minute segment on Fox and Friends and think they know all about me and my motivation for writing such “trash.” I never expected those strangers to e-mail me and call me a pervert or “a child preditor [their spelling, not mine] of the worst kind” for having written this book.

If I knew then what I know now, would I still publish this book?

You bet I would!

I’m proud of this book. I have to admit it wasn’t my idea to write it in the first place. My publisher wanted to publish a book that explained the facts of life to kids and they asked me if I’d like to take a stab at it. I was thrilled that they came to me with this project, even more thrilled when they liked the manuscript I produced. Some of my best fan letters have come in response to this book. Parents have written to thank me for helping them to “open the doors of communication” between them and their children. Teachers have written to tell me they were using it in fifth grade health classes, high school child development classes, and college children’s literature classes. I have a wonderful letter from a nursing student who says this is the best example of an “age appropriate book on pregnancy and childbirth” she’s ever seen. These letters and e-mails far outnumber and outweigh the hate mail I’ve received in response to this book.

Would I appear with someone else who wanted to challenge my book on a show like Fox and Friends again?

Honestly? Probably not.

I’m glad I did it. I’m stronger (and more resolved) for having done it. But I would likely not do it again. Why? Because I’m not sure it accomplished anything. It was a sensationalized, biased report. Most of the people watching the show had already made up their minds. They were absolutely certain my book was trash and that it doesn’t belong on library shelves, and nothing I said would ever change their minds. These people don’t see themselves as “censors.” They see themselves as “protectors.” Not only do they want to “protect” their own children, they want to “protect” everyone else’s, too. They just have a different definition of “protection” than I do.

They have every right to not like my book. They have every right to not read my book. But they do NOT have the right to prevent other people who might want to read it from having access to it.

Fortunately, those decisions are made by reconsideration committees in libraries. My appearing (or not appearing) on Fox and Friends will have very little bearing on what happens in a reconsideration meeting.

Albert Whitman & Co., September 2010.

So, how have I changed as a result of these challenges to my book?

First, I am more likely to speak up in defense of censorship now than I ever have been before. I’ve spoken to college students, civic groups, writers, teachers, and librarians about my experiences.

Second, when I hear of challenges to my book, I immediately e-mail the library where the challenge has occurred to offer my support and ask if there’s anything I can do to help. I understand now that when there is a challenge to one of my books, that challenge doesn’t just happen to me; it happens to a library and to an entire community as well.

Third, when I hear of a fellow author who faces a public challenge to a book, I e-mail that author to offer support as well.

If you’re ever invited to appear on national television to defend a community’s right to read your book, here are some tips:

Remain calm. It’s easy to get upset when you feel as though you’re being attacked, but you’re far more likely to get your point across if you can remain calm. You’re also less likely to look like a crazy person.

Know what you want to say ahead of time. Pick three points you want to get across and no matter what is said to you, just keep repeating those three points.

Wear plain, dark clothing. No busy patterns. Light clothing tends make people appear “washed out.”

Don’t be afraid to pause and take a moment to collect yourself before answering a question.

Understand that you don’t have to answer the exact question you’re asked. If you don’t like the question, steer the conversation back to one of your three points.

Realize that you don’t ever have to accept an “invitation” to appear on television if you don’t want to. You can send a short, written statement to be read on air instead.

Dori Hillestad Butler.

In addition to MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY, Dori Hillestad Butler is also the author of 39 other books for children, including THE BUDDY FILES, which is a chapter book series about a school therapy dog who solves mysteries. Her books are on children’s choice and teen award lists in 18 different states. THE BUDDY FILES#1: CASE OF THE LOST BOY won the 2011 Edgar Award for best children’s mystery. Dori is also on a quest to do an author visit in all 50 states. If she hasn’t yet visited a school in your state, your school is eligible for a discount. (Note: Dori does not discuss MY MOM’S HAVING A BABY during a school visit unless she is specifically asked to.) To learn more about Dori and her books, visit www.kidswriter.com

September 1, 2013

Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Robison Wells: The Context of the Terrible Thing

Although I have never had a book banned, I have felt the some small amount of the pain that those authors get.

HarperTeen, October 2011.

I live in a very conservative, very overtly religious state, and when I was first published it was by a very overtly religious publisher. Generally speaking, I toed the line and tried never to break the rules as to what words were acceptable and what words were naughty. But I still found myself being called into the principal’s office once.

Two of my characters were lightly arguing (my characters were religious, too, though not preachy), and the following conversation took place (I’m quoting this from memory):

He says something, evading the issue. Then she says “Woe unto the liar for he shall be thrust down to hell.”

He thinks: I knew the phrase well. (He gives the scripture reference.) My mother had it embroidered on a throw pillow.

That was it. That was what I was what I was getting called onto the carpet for. The word hell. The word hell, quoted as a scripture. The word hell, quoted as a scripture, when the scripture reference was given right there. No need to look it up. No question of where it came from. It came from holy writ. It came from the prophets, which means, according to my religion, it came from God.

HarperTeen, October 2013.

But “hell” is a bad word. It’s a swear. So out it must go. I took the issue to my editor, who agreed with methat they were straining at a gnat and swallowing a camel (to use another scriptural phrase). I took it to the managing editor whose only real response was “We’re going to get letters about it.”

Good! Let’s get a discourse open about what counts as a swear and what is a religious word.

Eventually it made it to “the committee” of all the important people and the story I heard later was that discussion was over before it began. Despite my objections, despite my editor’s interventions, it was published as “Woe unto the liar for he shall be thrust down to…”

Needless to say, I don’t work with that publisher anymore. I have, however, done book signings at the some of the same places and when I get the inevitable question of “Is it clean?” I always reply “VARIANT has seven hells, four damns, and a bastard,” just so they know what kind of apostasy they’re in for.

But I think the ultimate conflict (in this case of censoring books) is that that they were judging the Terrible Thing (swearing) instead of judging the context (two faithful, religious 20-somethings having a joking argument). In my case it was just silly, but think of all the cases where it has been hugely detrimental. Think of a book like SCARS by Cheryl Rainfield. Her book is about the very real, very dangerous social problem of cutting. And it might just get banned in your library (it has gotten banned in many) because—Oooh, cutting, I don’t want my kids to be reading about that! In truth, the book guides you step-by-step through a minefield, ultimately closing with a beautiful ending and an extensive resource guide. Again—many people judge the unopened book by the terrible thing that they think resides within it. They don’t look at the context. They don’t look at how the terrible thing is portrayed. As Cheryl Rainfield beautifully puts it: she writes about things that she wishes she had heard when she was a teenager.

Puffin Classics Edition, March 2008.

There will always be controversy, of course. As a reluctant reader all through junior high and high school, the book that finally converted me was HUCKLEBERRY FINN. I love this book with a passion, so I was leading the charge when a publisher said they were reprinting the book without the word “nigger.” I thought that word was so essential to understanding the historicity of the characters and the setting that to remove it felt wrong and crass. And yet there has been shown to be a large number of African Americans who are now able to experience the book—before they’d felt ashamed to read and discuss it—especially in places with a mostly white population. So is it better to censor HUCKLEBERRY FINN? Perhaps the easy answer is to read both versions and decide for yourself (though that seems a difficult task for an already overloaded English class curriculum).

And I hate to be the one to start off national Book Banning Week by saying “I don’t know… It depends, but I don’t know. It depends.” Do we want to have Madonna’s SEX in a kindergarten? Right there next to Howard Stern’s PRIVATE PARTS? Of course we don’t. So we don’t call it banning; we call it being age appropriate, and we make these decisions all of the time. We know there’s a line that we draw between what is age appropriate and what is not, and 98% of us agree that such a line exists: CARRIE in the first grade. A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: the Pre-School Edition. A line exists. This discussion of censoring books all comes down to where you draw the line. And everybody’s going to draw it differently.

But I’m right.

Robison Wells.

Robison Wells lives in Holladay, Utah, with his wife and three kids. He recently finished graduate school, during which he read and wrote novels when he should have been studying finance. His newest novel, BLACKOUT, goes on sale October 1st, 2013. He is also the author of VARIANT and FEEDBACK. You can visit him online and read his blog at www.robisonwells.com or follow him on Twitter @robisonwells.

August 27, 2013

Guest Post from Gwenda Bond: On Reinventing Legends

I asked Kristin for a suggestion of what to write about here–because it gets hard coming up with topics sometimes and I would always rather write a guest post about something someone else is interested in. She suggested I talk a little about working with established legends, history, and mythology, since both my books draw on them, and so that’s what I’m going to do.

Strange Chemistry, September 2012.

Probably the biggest single reason for this commonality in my work so far (and my next book, while set in the modern day also draws on the history of the circus) is that I write from my obsessions and interests. As a writer, I’m first and foremost a reader and a magpie–I think most of us are. And we all have certain shiny objects or topics that attract us more than others. If you’re a writer, published or not, I bet you have at least a couple different rows of books (if not more) that would count as “Research” on any given topic. And, of course, there are also kinds of stories that attract us, as readers and writers.

So, when I have an idea and it begins to accumulate the kind of mass that tells me it’s a book, often it comes from a combination of these things. It has one of my obsessions or interests at its core, and that comes together, like magnets attracting, with a story that feels right for it. Even though I hate beginnings, and they’re always hardest for me, my favorite moment in the writing process is still probably that time when an idea starts to become a story and it begins to unfurl in my mind…snatches of scenes, character moments, dialogue. None of them may ultimately end up in the story, but that’s when I know I have a story. I promise I’ll get around to the working with established legends and mythology part, but first one more larger thing.

There’s a term I came across years ago that stuck with me, and got bound up in the way I think about and create stories: mental real estate. I believe I first encountered this via Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio’s Wordplayer site (and if you google, you can find the column). But it essentially points out that in a world filled with stories competing for people’s attention that one thing that can help you is if the stories you tell also bring with them elements that already own a piece of mental real estate in someone’s head. By writing from my own obsessions, I’m gambling there are some other people out there who might share them.

BLACKWOOD takes the well-known historical mystery of the Lost Colony of Roanoke and transports it to the modern day. It’s a mash up of the old and the new–historical figures like Eleanor Dare and John Dee crashing into our modern world and two very modern protagonists. People often ask me about the pop culture references in BLACKWOOD, and they are so much a part of Miranda’s character and felt really necessary to me to rub up against the historical references. The friction of worlds colliding. It wasn’t until well into the research for that book that I came across the reference to John Dee that provided me with the connection to alchemy–another long-time fascination–that ultimately unlocked the whole story.

Strange Chemistry, October 2013.

THE WOKEN GODS is quite a bit different. For those who don’t know the set up, the book takes place in our world, where five years earlier the gods of ancient mythology woke up around the globe. The protagonist is a teenager in a transformed Washington, D.C., where she gets pulled into high stakes intrigue with the Society of the Sun and the seven tricksters who negotiate with humanity on behalf of the gods.

Obviously there are several oceans worth of mythology when you’re talking about all the gods of ancient mythology. And I went through several incarnations of this book along the way to the one that comes out next week. Ultimately, it was thinking about my favorite parts of mythology and a nonfiction book I’m obsessed with, TRICKSTER MAKES THE WORLD by Lewis Hyde, that led me to the idea of using a handful of tricksters that were the ones who’d volunteer to work with humanity. I knew I wanted the book to be set in D.C., and that I wanted a (no longer) secret society, but I also wanted to add my own twists to those things. There’s a big difference, to my mind, of being aware of mental real estate and engaging in lazy storytelling because it’s easier to default to the familiar.

Once I got to that concept, I still had to decide which tricksters and other gods I wanted to use and also create them as characters. Because here’s the thing–mythology is not internally logically consistent. Much of it developed over long periods of time, and that means that gods morphed into other gods, migrated into new pantheons, that personalities changed along with political circumstances, that the gods themselves behave differently in different myths. Because I’m working with gods generally less familiar to many people, I had more freedom to not have to battle existing ideas of them. But, still, I had to decide which pieces I wanted to take and which to leave, and then, the hardest part, make them into new myths, the versions in this new world. One of the things that makes me happiest so far is that many of the early readers seem to read the Tricksters’ Council and all its attendant architecture almost as something I borrowed… And I love that, because it means it feels mythical to them.

I have rattled far beyond my welcome, I’m sure. But thanks for hosting me!

Gwenda Bond.

Gwenda Bond is the author of the young adult novels BLACKWOOD (Strange Chemistry, out now), THE WOKEN GODS (Strange Chemistry, Sept. 2013), and GIRL ON A WIRE (Skyscape, 2014). BLACKWOOD is currently in development as a TV series by MTV, Grammnet Productions, and Lionsgate TV. She is also a contributing writer for Publishers Weekly and regularly reviews for Locus. She has an MFA in Writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and lives in a hundred-year-old house in Lexington, Kentucky, with her husband, author Christopher Rowe, and their menagerie. You can find her at www.gwendabond.com or on twitter at @gwenda.

August 6, 2013

Review: LOVE IN THE TIME OF GLOBAL WARMING by Francesca Lia Block

I love a good mythology book. I also love a good retelling of a classic. In her latest, Francesca Lia Block manages to blend the mythology and themes of The Odyssey with a story of survival in a post-apocalyptic Los Angeles.

Henry Holt & Co., August 2013.

On the day the Earth Shaker came, Penelope was in her family’s pink house in a nice neighborhood in L.A., feeling average teenage feelings — love for her friends, annoyance at her brother, and the slightest bit of resent toward her parents (who were both paranoid about chemicals in health products and the possibility of natural disaster). Now calling herself Pen, trying to shed the identity that she had Then, she is forced to leave her home when marauders come. She is surprised when one of the men doesn’t attack her but tells her to run, take his van, and leave.

Pen’s first stop is a big box retail shop, where she raids the aisles for supplies, shocked to find it hasn’t already been looted. But soon she discovers the monster who has taken up residence at the store. A half-blind giant. Fighting for her life, Pen takes out the creature’s other eye. She now knows there is no going back to Then. And she goes on, her only hope finding her family. And along the way, she finds others. First of all, Hex, the beautiful boy at the Lotus hotel. He has secrets of his own, but Pen needs an ally. With only a tattered copy of Homer’s The Odyssey and a sliver of hope to guide them, they have a whole new world to navigate.

In a style that is Francesca Lia Block‘s alone, LOVE IN THE TIME OF GLOBAL WARMING is heartbreaking and true and beautiful in a way that only this author can write. It is not only a story that parallels the Odyssey, but that approaches the popular trope of dystopia with a touch of magical realism. With characters who are both dreamy and strikingly real, a voice that must be heard, and a landscape that feels frighteningly true to a possible future, this is a book that can’t be missed. I’d love to see this one with some shiny stickers on its cover come award season.

August 2, 2013

Review: THE WEIGHT OF SOULS by Bryony Pearce

This brand new book by Bryony Pearce has three of my favorite topics to read about:

1. Murder

2. Ghosts

3. Bullying

Strange Chemistry, August 2013.

Does this make me dark? Or perhaps the author? Or are we looking at a story that looks at reality through the lens of paranormal fiction? I’d like to think it’s the latter. And I think that this is one of the many things that makes THE WEIGHT OF SOULS brilliant.

Taylor Oh is a student who is the bottom of the totem pole at her London high school. She’s picked on relentlessly by the cool crowd, even to the point of physical violence. Racial slurs are thrown at her, she’s tormented daily,and between this and her freaky secret, she never quite feels safe. Having recently lost one of her oldest friends to the popular kids, she now worries that her best friend Hannah will be the next to drop her.

The problem is, even if Taylor shared her secret with Hannah, she wouldn’t believe her. Taylor sees the ghosts of murder victims. And when the ghosts spot her, they leave her with a mark — a mark that could kill Taylor unless she finds the murderers and transfers it to them before the Darkness comes. Even Taylor’s father doesn’t believe the truth. A survivor of the accident that killed Taylor’s mother, Mr. Oh is determined to find a cure for the family curse. With science. And he is getting more and more exhausted by Taylor’s insistence that she needs to skip school, stay out late, and put herself in dangerous situations to help ghosts. According to Taylor’s dad, Taylor’s affliction is a combination of a skin condition and hallucinations. But Taylor knows the truth, and when one of the biggest jerks in school turns up missing, it’s up to Taylor to solve his murder. She’s the only one who can see him, and the only one who knows he’s dead.

THE WEIGHT OF SOULS is not only riveting and rife with action, but heartfelt and beautiful. The humanity of the book strikes just as hard as the mythology. Bryony Pearce draws on Egyptian lore to create Taylor’s world, and on the reality of teen life to create the characters around her and the social conflicts she has to confront. This is an up-all-night read, the kind of book that is terrifying and exciting and heart-wrenching. THE WEIGHT OF SOULS is not to be missed this summer, and I hope you’ll go find yourself a copy soon!