E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 8

April 26, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Sonya Vatomsky: I Was a Teenage Poet

I wrote my first poem when I still lived in Moscow, which means I was younger than six — I remember nothing from it except that it was about a raven or blackbird or crow (whichever one means ворона) and that that’s a particularly funny thing since there’s no way a small Russian girl in the late 80s had any familiarity with Edgar Allan.

Porkbelly Press, 2015. (Art by Shannon Perry of Valentine’s Tattoo in Seattle.)

It was pure poetic impulse or, more likely, something I saw in a park.

In 1991 we moved to the States, and my poetry collection continued somewhat bilingually. I still had the original Pushkins of my childhood, but new gifts would frequently arrive in English. I received Joseph Brodsky’s To Urania, which remains my favorite despite the fact that it’s been loaned to so many apathetic boyfriends that I’m probably on my fifth copy. Brodsky’s mentor Anna Akhmatova followed, along with Marina Tsvetaeva, and I learned from them as I wrote, mixing Brodsky’s strangely-placed line-breaks with Akhmatova’s intensity with the feelings of a modern teenage girl worried about divorces, crushes, and alienation.

As such, my exposure to American and English poets is both minimal and largely unpleasant; I remember hauling some giant tome of Great American Poetry to my room from my mother’s bookcase and going through the entire thing and finding ONE poem that I thought was any good, which turned out to be Sylvia Plath’s Lady Lazarus. The few scraps offered throughout my school curriculum bored me, I abandoned literature for linguistics during university studies, and I didn’t get an MFA. The result of this is that, as a Russian-American poet raised on Russian poetry and then Sylvia Plath and then no one, I have both long felt that I have no role model and that I’ve completely missed the memo on sentiment.

We’re supposed to avoid it, right? Feelings are out of vogue and the “legacy” of “alt lit” has left us with a poetic landscape where I’m more likely to read a poem about coffee and laptops than one navigating human emotion. This proved itself a bit of a quandary when, after a few years of the occasional quarterly poem, I got serious about writing and publishing — and found that I was made up, almost entirely, of emotion.

The thing with poetry is that while you don’t need it to sell, exactly, you do want it to have an audience. If you’re not going to make any money — if there’s no way this void into which you throw your time and energy night after night will financially support you — surely it can, at the very least, resonate? And here I turn back to, again, the Symposium on Sentiment that poet Staci R Schoenfeld sent to me the other week when I was probably going off about the lack of diversity in the Western literary canon. The symposium is a fascinating discussion on sentimentality and what place it has in poetry past and future and, not altogether surprisingly, it’s the essays by women that are the most striking.

Sylvia Plath.

It’s “women’s work,” after all, that so frequently gets tossed aside with accusations of sentimentality. Love? Sentimental, unless you’re a man in which case you’re probably brilliant. Childbirth? Sentimental, don’t even go there, please don’t ever mention your body like that. Loss? Sentimental, unless you’re a man and you’ve lost another man and you’re maybe both soldiers or something. To me, the fight against sentimentality strikes me so much as a feminist issue because while arguments can be (and were, by Kevin Prufer) made about the True Definition of sentimentality and so on, the fact remains that a patriarchal distaste for certain types of emotion has been systemically used to oppress women for centuries.

And so, there’s something a little radical in being emotional and visceral in contemporary poetry. In perhaps the most powerful essay of the series, Rachel Zucker writes about her experience creating poems referencing pregnancy and birth and motherhood. “The poem kept telling the story of the birth,” she says, describing earlier attempts to capture her emotions with words, “but wasn’t getting at the experience of it.” Something about the linear narrative, the I drank the coffee / The laptop showed things that were bad; I felt indifferent / A bird flew by and it meant something but not to me style of contemporary poetry is doing emotion a disservice.

“To write the clean, linear poem,” she continues, “was to participate in a culture that tries to silence women and misrepresent women’s experiences.” And the whole point of poetry, really, is to represent experiences, isn’t it? To convey with lyricism a visceral state unreachable through even the show-not-tell of prose, because good poetry one-ups that with feel-not-tell, an instant knock-knock on your amygdala.

Zucker ends up penning what she calls a “broken” poem, because that was how she felt. I, in turn, wrote grotesque poem after grotesque poem, feeling a spark of recognition when I came across the term “body-horror” describing works by David Cronenberg et al — works where the decay, mutilation, and destruction of the body are the principal sources of horror. I didn’t want to write a horror collection, though — I wanted to express my feelings in the most authentic way, and I tempered the destruction with pastoral imagery, flora and fauna, and with the ritualistic process of cooking, which often served as the metaphor through which the body is destroyed. I identified so strongly again with Zucker when she describes her first book, Eating in the Underworld, which is “a series of poems told through the narrative arc of the myth of Persephone.” Almost no one knows the back story behind the poems, she writes, because, “by speaking through Persephone, autobiography is subsumed or strained out or refracted.”

My forthcoming chapbook from Porkbelly Press (pre-order it here), MY HEART IN ASPIC, is about the trauma I experienced in the aftermath of sexual assault. But it’s also about fear, and disembodiement, and monsters. It’s about milk-white moons and drunken suns, armfuls of anise candies and a sprinkling of paprika. It’s about how dying is an art, like everything else. It’s about antagonistic line-breaks and imagery that hints at suffering and ripples back to stillness. It’s about thinking feelings and eating thoughts, and the other way around. It’s about revenge and acceptance and anger and thick, buttery sleep. It’s about opening with a quote by Marina Tsvetaeva and closing with I don’t know who won / but I think it was me. It’s about experience made magic, and that’s that. It’s a thin, faint heart on a yellow pad. “This will be me: no insides in thrall. Stare at it a while, then erase the scrawl.”

Sonya Vatomsky.

Sonya Vatomsky is a Moscow-born, Seattle-raised feminist poet and essayist. Her first chapbook, MY HEART IN ASPIC, will be published by Porkbelly Press in 2015 and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in No Tokens Journal, VIDA: Women In Literary Arts, Hermeneutic Chaos, Bone Bouquet, Weird Sister, and elsewhere. She is an assistant editrix at Fruita Pulp and can be found online at sonyavatomsky.tumblr.com & @coolniceghost.

April 25, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Ellen Hopkins: Painting the Verbal Landscape

Thirteen years ago I had an important story to tell. My family had experienced six years of addiction, through my oldest daughter. She had just gone to prison, and this mother’s pain, anger and confusion needed an egress. Words were the key. But they had to be the right ones, expressed in exactly the right way.

Margaret K. McElderry, Reissue Edition, August 2013.

As a long-time freelance journalist and recent nonfiction author, I was competent at putting words down on paper. Storytelling, however, was different. Yes, I had a story, but what was the best way to tell it? I knew from the start the novel’s audience was young adults, and I understood they’d want to hear from “Kristina,” not me. I started Crank in prose, but the voice was mine, not hers.

I put the project on hold and did a poetry workshop with Sonya Sones, whose memoir in verse, STOP PRETENDING, had recently made quite the splash. The book, about her sister’s struggle with schizophrenia, was hard hitting, real, and close to what I wanted to accomplish with CRANK. And now I knew how to tell it. In verse.

Before journalism, before nonfiction, I wrote poetry. I’ve always been attracted to the idea of painting a complicated verbal landscape with minimal brushstrokes. I published my first poem—a haiku—when I was nine, and continued to publish poetry throughout high school and into college. In my twenties, writing took a backseat to raising a family and running a business, but in whatever spare time I could find, I managed a poem or two.

Eventually, I moved to Carson City, where I connected with a well-established writer’s group, Ash Canyon Poets. Its intrepid leader, Bill Cowee, was an accountant with an affinity for Billy Collins, Sharon Olds, Robert Haas and Jane Hirshfield. He also wrote exceptional poetry about the fragility of nature and love and family. Bill took me under his wing and through his tutelage, plus outstanding group critique, I learned more about poetry than I ever did in school. The “rules” he encouraged were simple:

Rule #1: Poetry must be accessible. If readers have to work too hard to find meaning, they’ll quit reading. Invite them in. Allow room for interpretation. Give them a final image they’ll think about for days.

Rule #2: Write your poem, then put it away for a day. Now look at the first stanza. Does it belong there? Often, you’ll find it’s “scaffolding,” or how you found your way in. And very often your poem really begins with stanza two.

Rule #3: Imagery trumps diction. Both are important, of course, and diction feeds imagery. But without that verbal scenery, poetry is pointless, and a relentless focus on diction can backfire. Never rely on rhyme, and if you choose to use it, consider internal or slant rhyme. Meter is rhythm, not syllable count, and integral to free verse, too.

Margaret K. McElderry, November 2015.

Rule #4: Revise. Revise. Revise. No poem is perfect the first time you finish it. Sometimes that does mean tucking it out of sight for a time. It takes fresh eyes to find flaws.

And my favorite:

Rule #5: Revise toward mystery. This is where word choice becomes critical. Use the fewest possible brushstrokes to paint your landscape. And remember yours are the eyes the reader sees through, but you don’t necessarily belong in the poem. Your goal is to be a universal viewfinder.

I would add another rule of my own. Experiment. While I write almost exclusively free verse, I have also immersed myself in writing formal poetry, including ghazals, terzanelles, villanelles, sonnets, and rhymed couplets. Formal poetry comes with a whole set of rules, which is why many people prefer to write it. For some, it’s easier to follow rules than to make your own. For me, I enjoyed conforming to rules so I could learn to break them.

Ghosts

by Ellen Hopkins

Even a small bed is too big, alone.

She lies half-awake, draws stuttered breath,

listens to memory’s bittersweet drone,

wonders if silence comes cloaked in death.

Almost awake, she draws stuttered breath,

promises shattering on her pillow.

She wonders if silence comes cloaked in death,

as her storm clouds begin to billow.

Promises shattering on her pillow,

she conjures the image she cannot dismiss,

seeding her storm clouds. They billow

with the black remembrance of his kiss.

She conjures the image she cannot dismiss,

summons the heat of his skin on her skin,

the black remembrance of his kiss,

desire, abandoned somewhere within.

She summons the heat of his skin on her skin,

opens herself to herself, in disguise,

recovers desire, abandoned within.

Heart beating ghosts, she closes her eyes

And opens herself to herself, in disguise,

listens to memory’s bittersweet drone.

Heart beating ghosts, she closes her eyes,

knowing her small bed is too big, alone.

And while my novels would be considered narrative verse, which tells a definite story, I love the beauty of lyric poetry, which I write mostly to make myself happy. I’ve even attempted cowboy poetry. “Call to Love,” in fact, won second place in a national contest judged by cowboy poet Waddie Mitchell.

Call to Love

by Ellen Hopkins

I looked for love in the city,

where neon strangles the night

and jet planes swallow the song of the wild,

smother God-given delight.

Wand’ring cold streets, I looked in dead eyes,

empty as pale desert sand,

‘til my hungry heart’s cry sent me searching

for the solace of unfenced land.

I followed God’s call to the country,

where His hand paints landscapes fair.

I thanked the Lord for the eagle’s cry

and the perfume of rain-gentled air.

He led me to my heart’s desire,

riding rough beneath star-choked skies.

I met happiness there in a cowboy’s smile

and found love in the depths of his eyes.

So, poets, try something new. Something different. Don’t stagnate. Grow. Play with form. If you rely heavily on rhyme, challenge yourself to write nothing but free verse for a while. Find a mentor. Listen to critique, but take away only what makes sense to you. Write your poem. Put it away for a day. Then revise toward mystery.

I leave you with this mother’s voice in a poem about her addict daughter.

The Significance of 26

by Ellen Hopkins

I don’t belong in this place, with its blood

purple chairs and glacier gray walls,

where fractured lives converge,

exchange

embarrassed smiles,

pull numbers

and trade IDs

for zipper striped passes.

I don’t want to be here.

But Tuesday is visiting day.

In a starched, blue blouse, I feel

absurdly like Alice, cast into a Wonderland

of empty-eyed mothers,

eager-legged toddlers

and trash-tongued lovers,

Tuesday regulars.

I am down the rabbit hole,

chasing a glimpse of a stranger.

We wait, chancing glances

at our fellow numbers, ones, fours and sevens

young and straight in their chairs’ embrace,

threes and eights squirming

against the greasy donut dance,

twos pacing. The rest study the floor.

I am number 26,

a whiff of cosmic mockery.

“Number 24!” Deputy Kathy arouses

him, older than his years, hardened

by his habits, uncomfortable with cleanliness.

He considers his shirttails, forgetting

steel-toed work shoes.

The metal detector remembers.

I carry no purse, no keys.

My Nikes need no inspection.

Cameras track me down soulless corridors,

red, white and blue lines directing.

The white one turns left, down

the stairs, steel doors slamming

behind me, just like in the movies,

except I am free.

I am free behind a row of smudged

windows and sticky telephones.

Closest the door, Number 24 talks to his tattooed

wife of newly ordinary life. “That’s good,” she says

through a half-painted smile, then asks,

“How are the babies?

“Fine,” he says, “I get up every morning

to see they go to school.”

I feel somehow grateful for that.

And wonder again why I’m here.

And then I see her, Mata Hari in the hallway,

a shadowy resemblance to the child

I thought I knew. She looks better

than the last time we met,

put on some weight with jail

food and another pregnancy.

I choose a window and pick up a handset.

She decides what to say.

No sign of self-induced confusion, her eyes

meet mine through un-wiped fingerprints,

crocodilian defense brewing in aquamarine.

“I was afraid to call, afraid

you’d stopped loving me.”

I scour every word, wanting

only to hear I’m sorry.

But she has never offered apologies

and now says only, “I couldn’t, I wouldn’t, I’d never!”

Then she laughs and confides her sentencing

is March 26th, my birthday,

and could I put twenty dollars into her account?

She’s craving a candy bar.

I’d hoped to forgive her.

Instead, I tell her, “Orange does not become you.”

Ellen Hopkins. (Photo by Sonya Sones).

Ellen Hopkins is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of eleven young adult novels, as well as the adult novels Triangles and Collateral. She lives with her family in Carson City, Nevada, where she has founded Ventana Sierra, a nonprofit youth housing and resource initiative. Visit her at EllenHopkins.com and on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter at @EllenHopkinsLit. For more information on Ventana Sierra, go to VentanaSierra.org.

April 24, 2015

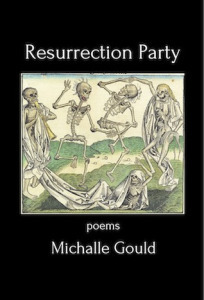

National Poetry Month: Guest Post From Michalle Gould: When Is It Enough?

Putting a book of poetry out on the world can feel like an unusual way of testing your personal relationships. It is hard not to find yourself asking questions that it would probably be better not to think about. Who has bought my book? Have the people who bought my book actually read my book? Did they like it? Did they hate it? Did they finish it? When will people start adding reviews on goodreads? When will people start adding reviews on amazon? That person said they were going to buy my book, but it doesn’t seem like they really have. How can I get more people to buy my book? How many times can I talk about it on facebook without people hiding me? How many times can I talk about it on twitter without people unfollowing me? Am I turning into a monster for thinking about any of this? Is this something I should be admitting in writing?

Silver Birch Press, August 2014.

But it’s your book! You’ve worked on it for so long! In my case, I worked on it for nearly fifteen years! Back in 2002-2004, just after I finished my MFA, everything seemed to be headed in the right direction. My poems were published in Slate, New England Review, and Poetry, all completely out of the slush pile. My manuscript was a semi-finalist or finalist in a few book contests and solicited to enter an open reading period. I felt sure that my book was about to be published. And yet for whatever reason, I found myself slowly but surely submitting less and less. I still entered contests but fewer and fewer. I still sent my work out but far less frequently. It is hard to put my finger on why, but I think one reason was a fundamental crisis about the direction those achievements were taking me and how that might be affecting my writing. For most poets who enter MFA programs, the end goal is clear – to eventually publish a book. But a part of me was unsure that I was entirely ready, as well as about the effect that giving the book primacy as the end-goal of writing, the mark of “success,” might be having on my writing of individual poems.

Publishing a book feels so final – it can appear to impose a sense of conclusion upon a body of work, to harden it into a structure of meaning that may not have existed when you were writing its individual components. Readers of a book will inevitably look for overall themes and relationships between the poems, to presume that you had some overall intention in mind for the poems taken as a whole. Furthermore, the contest system for getting first books (and lately second and third and all books) published may subtly encourage writers to anticipate this by consciously linking their poems – whether it is the truth or not, it can definitely feel that a project book, defined here as a book of “poems that surround a central idea,” has a significantly better chance of catching a screener or final judge’s attention than a book of good but unrelated poems.

I worry that this distorts the type of poems that are being written, that this can subtly steer writers away from poems that do not “fit,” that do not deal with an identifiable theme or subject. At times I could feel myself writing “to” the poems that already existed in my book, not wanting to expend time or energy working on something that wouldn’t have a vessel to contain it. While that was certainly my own choice, I found the pressures and environment that shaped that choice frustrating. I want to emphasize that I am not criticizing project books in and of themselves, just the possibility that poets who aren’t suited to that format may be pushed to write them by the current publishing landscape.

In some ways I resist the book as the primary “unit” of poetry. It is more natural to me to compare a favorite poem and a favorite novel than to think offhand of a favorite book of poems. A poem is a complete entity to me in the same way that a novel is a complete entity. I think this is also often true of those whose primary relationship to poetry is as readers of it rather than writers. This may be part of why sales of books of poetry are generally considered to be very low, despite the fact that poem-a-day sites and favorite poem projects are so popular, despite the prevalence of individual poems on trains and in bus terminals and readings at weddings and funerals.

So where does that disconnect arise from? And if people are so disinterested in buying poetry books, why try to publish one at all, especially knowing that means subjecting yourself to the somewhat degrading-feeling cycle of questions listed above, the necessity to self-promote even though, as described vividly by poet Tim Green here, you will generally be promoting your book mostly to “1,000 other poets trapped in the same nauseating self-promotional pie-eating contest,” with their own book to promote and their own poet friends’ books to read and no time and energy for yours, rather than the broader audience that exists for novels and memoirs.

Although writers, on the one hand, share the responsibility with publishers to think about the first question and how to change the situation as it stands, at the same time, I think we also eventually need to ask ourselves the question, “When is it enough?” When is it time to let go – to stop worrying about whether people are buying it, whether they are reading it, even whether they like it? It’s hard to do because it can feel like those things impact our ability as poets to publish other books in the future. But when the pain begins to outweigh the pleasure, there is basically no other choice than to return to the more fundamental and original starting point, the simple task of trying to write one good poem.

Michalle Gould.

Michalle Gould is a writer and poet who worked on the poems in RESURRECTION PARTY (2014) for some 15 years before publication. She currently works as an academic librarian in Los Angeles and is also writing a novel set in the north of England in the 1930s.

April 23, 2015

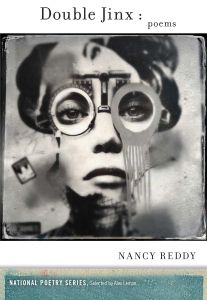

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Nancy Reddy: Finding Humor in the Poetic:

During my MFA, I was lucky enough to work with the poet Ronald Wallace, who is truly the kindest soul I ever hope to meet. Really, though – before we’d met, he sent me an email with comments on my work so nice that I showed it to my husband and asked, “Do you think he’s somehow making fun of me?” He wrote meticulous pencil notes on the poems that I brought to him, and he made copies of those comments for his own reference so that he could compare revisions.

Milkweed Editions, September 2015.

And so it was a surprise when, after handing him the first big pile of poems that eventually became my thesis, he looked up and said simply, “not much funny here.”

Funny? I’d had no idea that poems could be funny – certainly not outside of Shel Silverstein or nursery rhymes. And besides, I’d first started writing poems as a teenager because I had Feelings, and those feelings were Not Funny. The poets I loved most then were Louise Glück, Carl Phillips, Larry Levis – poets of lyric density and heartbreaking revelation. Not much funny there, either.

But I trusted Ron’s (gentle) suggestion, and I started trying to lighten up a bit in my writing, beginning the only way I knew how – with books. Ron’s poetry funny isn’t necessarily mine, though he does have lovely poems about, for example, explaining to his young daughter where babies come from that manage to merge the humorous with the touching.

I found two poets, though, who helped me learn how to stop taking myself so seriously – and to do it without losing the intensity and urgency that brings me to poetry in the first place. Matthea Harvey’s MODERN LIFE is populated by robots and mermaids and fish, and it veers wildly – thrillingly – from quirky to heartbreaking. While the first poem, “Implications for Modern Life,” isn’t exactly funny, it does have moments of sharp, surreal description, beginning with its opening sentence: “The ham flowers have veins and are rimmed in rind, each petal a little meat sunset.” I find those ham flowers simultaneously gripping, horrifying, and tremendously moving. I don’t think, before reading that poem, that I’d had any idea poems could do that – that they could render a world so strange and yet so compelling.

Catherine Pierce’s THE GIRLS OF PECULIAR, on the other hand, brought me a world so familiar I still feel I might have written some of those poems, if she hadn’t gotten there first. (This is wishful thinking.) “Oregon Trail, 5th Grade” pitches an astute player of that game against her less-strategic classmates: “The other kids / are idiots, loading up on clothes and corn, /but you know the trick: ammo, oxen, and luck.” This speaker is merciless and acerbic when the video-children die, noting with some satisfaction a player’s death to typhoid: “You fill out the grave, guiltless, gleeful: / Here lies Clara, a proper fool. Typhoid sounds to you / like a windstorm, like dumb Clara died when her heart / thrashed too hard against the limbs of her ribs.”

Now, Ron might still remark that there’s not much funny in all this, and perhaps he’d be right. But those poets taught me about tonal range – that I could bring in parts of my world beyond the snow and bare trees and solitude that obsessed me at the time, that I could move beyond the melancholy that had become, somehow, my default tone.

This gentle prodding from Ron helped me to write all kinds of things I wouldn’t have otherwise – poems about beauty queens, Snow White, Chicken Little, Little Red Riding Hood, vampires. Some worked. Some, not so much. (Chicken Little never quite got off the ground, alas.) And along the way I’ve learned something about being at least a little bit funny in my poems. The title poem to my forthcoming poem, Double Jinx (http://milkweed.org/shop/product/376/), owes a great debt to that one comment from Ron. Its full title is “The Case of the Double Jinx,” and it takes up Nancy Drew, her many disguises, adventures, and misadventures. It begins with two lines that often get a laugh at readings:

You’re Nancy Drew and you drive a blue coupe.

You drive fast. Your mother is dead.

I’m not sure if that’s the kind of funny Ron had in mind, but I wouldn’t have written it without that push. My book is much weirder and wilder – funnier in places, but darker, too (poor Ned ends up on an ill-fated Alpine ski trip, bound and gagged in the basement of an inn; the poem ends with Nancy ultimately asking wondering if “she’s the real Nancy / and you’re a costume party”) – for that encouragement.

Nancy Reddy.

Nancy Reddy‘s poems have been published in 32 Poems, Tupelo Quarterly, and Best New Poets of 2011 (selected by D.A. Powell), with poems forthcoming in Post Road and New Poetry from the Midwest. She holds an M.F.A. from the University of Wisconsin, where she is currently a doctoral candidate in composition and rhetoric. She lives in Madison, WI.

April 22, 2015

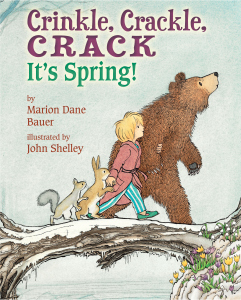

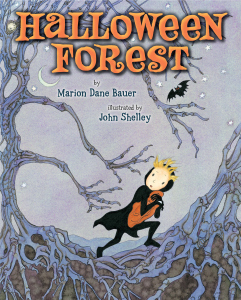

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Marion Dane Bauer: I Am Not a Poet

I am not a poet, but I do love to write verse.

I don’t make that distinction out of false humility but out of reverence for poetry and for those who create it.

Holiday House, April 2015.

True poetry requires a freshness of language, the kind of unexpected encounter with words that can make the hair rise on the back of your neck. A longtime friend of mine, the poet Barbara Esbensen, used to talk to children about bringing two words together that had never met one another before. I can do that once in a while, but the encounter requires a fair amount of serendipity.

What I can produce intentionally and reliably is work that is lyrical. I revel in rhythm and sound and the shape of the words on the page. I can write succinctly, too, and with close attention to what is left out, the unspoken that will resonate in my reader’s psyche.

Picture books, every picture book worthy of the multiple readings young children so often call for, use all of these techniques. And they are, of course, the techniques of poetry whether they reach the full status of poetry or not.

My most recent picture book, CRINKLE, CRACKLE, CRACK: It’s Spring!, illustrated by John Shelley (Holiday House), is a case in point.

I work with sound, lots of sounds. Not just the sounds that the characters pursue, trying to find their source: “crinkle, crackle, crack, rap, bap, tap, crunch, scrunch.” But I let the sounds of the more ordinary words telling the story flow for reader and listener alike: “You’d pop out of bed, / you’d creep to the door, / then you’d step outside to see . . . / mud, / rotten snow, /trees shivering in the dark.” Note the repetition of p’s followed by the sudden stop of “mud, rotten snow,” etc.

Holiday House, September 2012.

I toss in an occasional free-floating rhyme, too. “And oh . . . of course, / the bear. / The one standing there / in the middle of your yard.” When I’m writing board books for the very young, I usually work in a predictable rhythm and rhyme scheme: “How do I love you? / Let me count the ways. / I love you as the sun / loves the bright blue days.” (from HOW DO I LOVE YOU? illustrated by Caroline Jayne Church, Scholastic, 2009). But for slightly older readers such as those for CRINKLE, CRACKLE, CRACK, I prefer a more free-flowing line. “The bare bones of trees / stand on a hill / in the chill / breeze.” or “And together they’ll cry, / ‘Take care! / Beware! / Despair! / You can bet / you’ve just met / your worst nightmare!’” (from HALLOWEEN FOREST, illustrated by John Shelley, Holiday House, 2012).

The fact that I was playing with rhyme in that unpredictable way seemed to disconcert reviewers until my editor had the wisdom to use the jacket copy to provide information about the text. She referred to the text as “unmetered, rhymed verse.” Once given a name for what they were reading, reviewers quoted that phrase in their reviews and complaints fell away.

Perhaps the most important technique of poetry that picture books use is resonance. It’s the iceberg effect: 10 percent above the surface and 90 percent below. Of course, the text must hold back, leaving room for an illustrator to bring his or her own magic to the story; but the text needs to do what any good poem does as well, leave room for the one who receives the words to feel.

Holiday House, August 2009.

Resonance is more difficult to demonstrate without giving the entire text, but I’ll risk a brief example from another of my picture books, THE LONGEST NIGHT, illustrated by Ted Lewin (Holiday House, 2009). It opens this way: “The snow lies deep. / The night is long and long. / The stars are ice, the moon is frost, / and all the world lies still. / Bears sleep, as do the velvet mice. / A moon shadow lies by every tree, / thin as a hungry wolf. / ‘Sha-a-a,’ whines the wind, the bitter wind. / Cold and dark now rule. / Cold and dark now rule.”

If that text doesn’t induce an almost physical shiver, I’m not doing my job.

I’ll say it again. I don’t claim the name of poet for myself or call my work poetry, but the techniques of poetry enrich everything I create, especially when I am writing for the very young.

It is, after all, these techniques that make a story work through the multiple readings young listeners often crave. They do something more as well. They prepare those same listeners for the real thing.

Marion Dane Bauer.

Marion Dane Bauer is the author of nearly 100 books ranging from board books and picture books through easy readers, both fiction and nonfiction, and middle-grade and young-adult novels. Her picture books have made the New York Times Best Seller List and have won awards such as the Golden Kite Award for the best picture book text from the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) and a Mom’s Choice Award.

April 21, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Leslie Bulion: Hearing Music, Writing Science

Whenever I’m invited to join a lineup of poets I feel compelled to introduce myself with a Monty Pythonesque: And now for something completely different…

Peachtree Publishers, March 2015.

I’m a science poet. I write in verse forms, inventive schemes of rhyme and/or rhythm, and free verse, creating collections of poems that spring from and coalesce around one big idea. I’m inspired by the wonders of our amazing blue planet through reading, my own observations and lots and lots of research. Wordplay and ample doses of humor punctuate my joy in the richness of language, and the lexicon of science lends inviting rhythms and ear sounds.

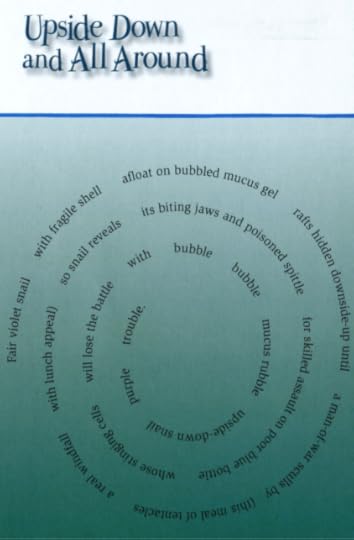

Although I came to a writing career in a roundabout, late-ish way, and to children’s poetry even later, I have been writing poems since the 4th grade. I’ve always loved the musicality of poetry, whether reading A. A. Milne, E.E. Cummings or Eavan Boland. I’m drawn to visual and rhythmic patterns in poems as well as emotion and humor. Memorizing and reciting poems as a fourth grader (thank you, Mrs. Brownworth!) taught me to recognize the rhythms and patterns that please my poetic ear. A steady diet of folk music of the ‘60’s and Broadway show tunes didn’t hurt, either. I’m sure these experiences laid the groundwork for the joy and satisfaction I derive from working in established poetic forms such as double dactyl, tanka, and triolet, to name a few, and to create patterns of my own. Here’s an example from AT THE SEA FLOOR CAFÉ: Odd Ocean Critter Poems:

Speaking of songs, tuning one’s poetic ear by using the rhythm and rhyme scheme of a song you know is excellent poetry practice. I’ve done this all my life for fun—for birthday parties, roasts and the like—without realizing I was preparing myself for a poetry career. When I visit schools, I use simple songs (e.g. “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”) and ask students to brainstorm rhymes and swap out a line. Then we rewrite the whole song to create lyrics about a different, familiar subject. Each group surprises me with something creative and new. Jon Scieszka’s SCIENCE VERSE is a brilliant example of this approach.

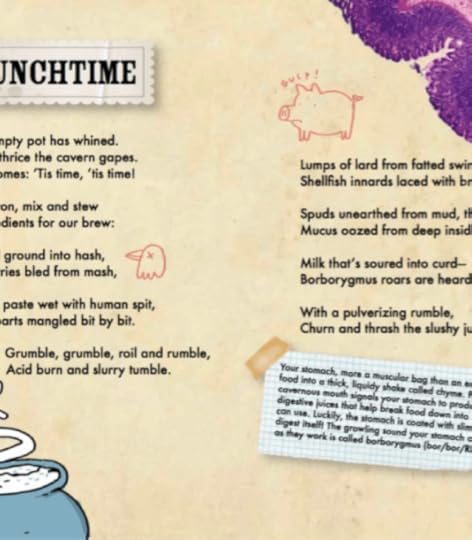

In my newest poetry collection, RANDOM BODY PARTS: Gross Anatomy Riddles In Verse, each riddle poem has a connection to Shakespeare, and several use Shakespeare works as direct mentor texts. This riddle uses the witches’ speech from MACBETH as mentor text:

Rhythmic and rhyming poetry has an inherent kinesthetic opportunity. When I’m working on a rhythmic poem, I go outside and walk it. Get up from your chair and try walking the words extra-dimensional, doodlebug or alveoli. See what I mean? Down the street and through the woods, my body paces a beat, and my brain shakes loose—in a good way. Stuck ideas clear out, and new ideas are free to jiggle in. During school visits, we clap rhythms and create rhymes. I see heads and bodies move with the beat and watch students’ focus, their “aha!” moments unfolding in front of me.

Free verse is a critical vehicle for expression, and sometimes teachers worry that by introducing rhythm and rhyme they will stifle students’ emotional connection to their poems. But even if we love love love broccoli, we don’t eat only that at every meal. Sometimes we enjoy carrots, sometimes rice, and sometimes chocolate cake, if we’re lucky, and that’s what keeps us well-rounded (yes, I’ve never met a pun I didn’t like).

Therein lies the beauty, and what I love most about poetry—it’s all different! There are no rules about requiring just one cuisine. Poetry is a banquet, a smorgasbord, beautifully illustrated on the #NPM15 poster designed by Roz Chast:

Ink runs from the corners of my mouth.

There is no happiness like mine.

I have been eating poetry.

(from “Eating Poetry” by Mark Strand, Selected Poems 1979)

Leslie Bulion.

Leslie Bulion combines science, humor and poetry in her gruesomely funny, award-winning science poetry collections RANDOM BODY PARTS: Gross Anatomy Riddles in Verse, AT THE SEA FLOOR CAFÉ: Odd Ocean Critter Poems and HEY THERE, STINK BUG! Leslie’s other books include the humorous, science-infused middle grade novels THE UNIVERSE OF FAIR, UNCHARTED WATERS, and THE TROUBLE WITH RULES, and the Children’s Africana Book Award Best Picture Book winner, FATUMA’S NEW CLOTH. A former school social worker with a graduate degree in oceanography, Leslie has written and edited books in the education market and has been a contributing writer to national magazines and on the internet. She gives workshops and presentations to students, educators and writers throughout the US and internationally via virtual visits.

April 20, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Joyce Brinkman: Two Pens Are Better Than One: Collaborative Writing

Humans are social beings. They share. They cooperate. They work together. This communal nature has existed since the beginning of our species. The Garden of Eden story tells us that in the beginning God said man should not live alone. Small prehistoric hunters took down large mammoths, saber tooth tigers and other fierce game by hunting in groups. Generals and kings rely on armies. The first ruler of China was so dependent on his that he had untold man-hours spend on creating terra cotta soldiers to accompany him in death. Not only was Roman not built in a day, it was not built by one individual. Julius Caesar didn’t cross the Rubicon alone, so why do we think poets should work alone.

Leapfrog Press, September 2014.

In America, at least, poets are thought of as quiet, reclusive people who would rather spend time with words than with people. They are viewed as lost in their own thoughts and disconnected from reality. This view is what I call the Thoreau/Dickinson syndrome. Because Thoreau enchanted us with poetry that grew from the peace of Walden Pond and Dickinson amazed us with her insights on life and death from a room overlooking a cemetery, Americans think writing poetry requires solitude, and today’s poets often seek such solitude in which to write.

I began writing poetry as soon as I learned to write, and for years I wrote by myself and for myself. Writing this way certainly isn’t without merit. Poetry provides wonderful exercise for the brain. It helps you express feelings and examine the world within and without. Poetry alone was great, but when the opportunity for writing poetry with others came my way I discovered even greater satisfaction.

San Francisco Bay Press, July 2008.

As a result of having my poetry selected to be used in a public art project at an international airport, I found myself involved with other poets who had poetry in the project. We discovered we had similar poetic interests, and thought we might expand on our project work to produce a book including those poems. We became known as the Airpoets, because of our work at the airport, and began writing together from monthly prompts. San Francisco Bay Press published two books from our collaborations, RIVERS, RAILS, AND RUNWAYS and AIRMAIL FROM THE AIRPOETS.

Many poets today have critique groups, but this collaboration was more than just bringing in individual work to have group members spot problems and offer suggested changes. With this group we had a group goal and structured exercises. It was a small yet diverse bunch as far as experience and training, but because of our shared vision and respect for each others’ work everyone benefited.

I found another even more integrated opportunity for collaboration with former Virginia Poet Laureate Dr. Carolyn Kreiter-Foronda. Carolyn had first fascinated me with her interwoven, two-voiced poems she calls “simultaneous poems”. I loved participating in reading them with her and even wrote a few of my own. In the meantime I had really become interested in Asian forms of poetry, so I asked our Japanese poet friend, Kae Morii, to join Carolyn and I in writing a kasen renku. This is a Japanese form of renga, or linked verse, which has 36 verses of alternating 5/7/5, 7/7, and 5/7/5 syllable counts. Kae wrote the 7/7 lines in between the 5/7/5 verses from Carolyn and I.

I began the Autumn renku in the traditional manner with an acknowledgement of Kae. Since she had recently left after visiting with us in the US, the poem took on a wistful sense of longing.

Fall’s moon does not shine.

Strom volleys hammer windows

Missing light and you.

My loneliness passes through

the road filled with bush clovers.

I feel you in fog

lingering past nightfall’s bell.

Hummingbird: stay! stay!

Stay! Merry light of houses

on silent water surface.

It proved to be such fun that we next tapped our Mexican poet friend, Flor Aguilera Garcia, to do a renku over the next summer. By the end of this renku, my mother was slipping deeper into Alzheimer’s disease and climate turmoil plagued Mexico and the Eastern US coast.

Ozone opening,

magenta madness expands,

breeds daughter’s distress.

Verses lay down on the roofs.

Hurricane kissed them good night.

Gale force storm silenced.

begonias sluggish in shade –

the catcall of sleep.

Fixed to us: dirt, dust, drama

of countless rainy seasons.

We couldn’t let the other two seasons of the year languish without a renku to commemorate them, so Carolyn suggested her German poet friend, Gabrielle Glang for Winter and then Gabi introduced us by internet to Catherine Aubelle of France who took on the challenge of Spring.

A year of renku completed, we placed the four poems together and decided we had a book and so did Leapfrog Press. SEASONS OF SHARING: A Kasen Renku Collaboration has all our renku in English as well as each of the poems written with our four foreign partners translated by them into their home country’s language. Collaboration took me in a very short time from a more isolated poet to this multinational, multilingual adventure in poetic sharing.

After finishing SEASONS OF SHARING, Carolyn and I began an editorial collaboration inspired by a collaborative poem we wrote with Flor. This became another San Francisco Bay Press publication titled URBAN VOICES: 51 Poems From 51 American Poets. Collaboration had become such a big part of my poetry life that I thought I should stop to examine the possible advantages of this type of writing. My analysis produced the following:

Ten Benefits of Collaboration

San Francisco Bay Press, October 2014.

1. Collaborating takes some of the scariness out of publishing.

Writing is fun. Search in for a publisher and getting rejections letters are not. Somehow it’s easier to have someone else there with you on that journey. This is a particularly good benefit for writers who are new to publishing, especially if they can collaborate with someone more experienced in the process.

2. You have fewer poems to write to make a book.

I love to write poems, but I am not overly prolific and left to my own whims I jump from subject to subject, style to style. I probably have 10 dozen book ideas that each has three to eight poems written. When I’m producing a book with others I have less material of a certain style, subject or direction to complete in order to have a whole book..

4. With collaboration different talents are brought to the table.

Most poets have their strong points. Some are more musical, others superior with imagery. In my collaboration with Carolyn I can always count on her superior punctuation knowledge, her dedication to quality.

4. You have someone to learn from and/or someone to teach.

In an effective collaboration each poet will be doing both teaching and learning. None of us are beyond learning no matter how accomplished we may be, and each member of a collaborative team needs to be ready to teach by sharing their techniques and advice with others.

5. Working with others keeps you on track.

There is nothing better for a procrastinator than working with someone else. When others depend on you, there is the extra push to get the work done.

6. A writing partner can introduces another perspective.

Writing poetry is a learning process in many ways and it can be enhanced by working with another poet. Seeing material from a new set of eyes can open our own minds to other possibilities.

7. Partnering provides inspiration.

That new perspective may just open up different approaches and inspire new work, and being part of a writing project where you see others produce fine work tends to elevate your own work.

8. A collaborator gives you someone to listen to your frustrations.

There are things involved in writing that can be frustrating. A computer crash when you’ve just finished your manuscript, a long wait for a publisher’s response, problems scheduling a reading series, an aggravating stanza that just won’t work. Your spouse, your children, or your dog may not be the best to sympathize with these things. They’d rather you talk about their interests or at least fill the water bowl.

9. Someone picks up the pieces when you drop the ball.

Things happen! We get sick. Our spouse has an auto accident. The house burns down.

And just when the editors need some corrections for the book, if you can’t deliver, a great collaborator can step in to keep things from crashing.

10. Working in collaborative ways is just plain fun.

As I said in the beginning, we humans are social animals. Working with others is in our DNA. Sometimes it is hard for those who are use to working alone to try collaborative work, but I’m convinced the work you do alone will be better as a result of working with others. Just give it a try and find out for yourself how two pens can be better than one.

Joyce Brinkman with her cat Bobb.

Joyce Brinkman lives in Zionsville, with her husband and a sweet cat. Her printed works include collaborative books, RIVERS, RAILS, AND RUNAWAYS, and AIRMAIL FROM THE AIRPOETS. She has received fellowships and grants from the Mary Anderson Center for the Arts, the Indianapolis Arts Council and the Indiana Arts Commission. Her latest book is the multi-lingual, international collaboration, SEASONS OF SHARING: A Kasen Renku Collaboration with Dr. Carolyn Kreiter-Foronda and four global partners.

April 19, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from A.L. Sonnichsen: Why Poetry?

A question I’ve been asked over and over again since my novel in verse came out is, why poetry?

I didn’t always write this way.

Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, February 2015.

I didn’t even know novels in verse existed until a few years ago when I participated in a verse novel challenge on Caroline Starr Rose’s blog. Her debut, MAY B., was about to be released and she was excited to introduce her blog readers to the genre. The challenge she gave was for each of us to read five verse novels.

I started with Karen Hesse’s OUT OF THE DUST. And I was hooked.

You can tell you’re hooked on verse when simply walking around your house, a place you inhabit every day, gives rise to inspiration. Verse swirled in my head. Every detail became a poem. If I dared step outside, the words only bubbled faster.

That’s the thing about poetry. It’s life and detail and metaphor. Not complicated at all.

Perhaps I always thought like a poet, though I didn’t realize it. I give all the credit to my mother. When I was a child, she matched my steps. Outside, we’d stop to linger over a flower, watch the slow crawl of a centipede across our path. When I became a teenager, her fascination with detail irritated me. I had places to go! My mom always seemed to be ten steps behind, calling after me, “Amy, look at this!”

But now that I’m an adult, I realize my mom gave me a gift.

I notice.

Water droplets.

The exact color of soap scum.

Fire in the sunset.

How long it takes for warm breath in frigid air to disappear.

Poetry gave me permission to capture those details, those intricacies of life that slip away too quickly.

And I found, through novels in verse, that I could tell a whole story through details.

Schwartz & Wade, January 2012.

Back to Caroline Starr Rose (because she’s a brilliant author and poet, to whom I’ll always be indebted) … she likens writing a novel in verse to piecing together a quilt. I love that analogy. Bits and pieces of fabric, sewn meticulously. These are your individual poems. Now the work begins of organizing them into a cohesive story.

Verse requires a gentle touch. It’s not the heavy brush of an oil painting, layer upon layer. It’s the tap of tweezers, fitting that sliver of glass into just the right spot in a mosaic. It’s the stepping back, taking in the whole, while admiring the unique glimmer of each shard.

This is why some writers choose poetry to tell their stories. Poetry offers a light touch. We take on tough subjects: abandonment, fear, isolation. Poetry allows us to frame those difficult subjects in beauty, to create art with them.

It’s not so unlike the mosaic master’s hammer, breaking pottery to bits in order to create something profound.

I barely consider myself a poet. I don’t rhyme. I rarely handcuff myself to form or meter. But I love language, the sound of words, the details: the grainy surface, the collection of dust, the finger smudge on glass.

Honestly, anyone can be a poet if she will but pay attention.

A.L. Sonnichsen.

Raised in Hong Kong, A.L. Sonnichsen grew up attending British school and riding double-decker buses. As an adult, she spent eight years in Mainland China where she learned that not all baozi are created equal. She also learned some Mandarin, which doesn’t do her much good in the small Eastern Washington town where she now lives with her rather large family. Find out more at http://alsonnichsen.blogspot.com.

April 18, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Cordelia Jensen: Constructing an Image System for a Verse Novel

My favorite part of writing verse novels—and maybe writing in general—is image construction. I am a lateral thinker and, for me, there is no greater sense of joy than when an image flies into my brain connecting two seemingly disconnected things. In my upcoming verse novel, SKYSCRAPING, I used celestial imagery throughout the book to convey the main character’s own existential crisis, he own search for meaning in a world that suddenly feels vastly confusing. I tried hard when writing this book, not to just think about a singular image working alone on the page, but how the main character’s experience with the sky would change as she did. I believe an image standing alone is often not as strong as an image system that evolves, gathering meaning over the course of a narrative. This is the way the “prose” part of a verse novel gifts the “poetry” part of the story.

HarperCollins, Reprint Edition, January 2013.

As a creative writing teacher, when I teach imagery construction is verse novels I focus on Thanhha Lai’s middle grade Newbery Honor book, INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN. The imagery in this book is simple—it is written from a fourth grader’s perspective. But it is powerful in its simplicity: The image of the papaya fruit changes in the meaning as the main character herself changes. For instance, when Hà still lives in Vietnam and her innocence is intact, the papaya fruit is a beacon of hope for the future:

I vow

to rise first every morning

to stare at the dew

on the green fruit

shaped like a lightbulb.

I will be the first

to witness its ripening.

As fear infiltrates Hà’s world, the fruit remains beautiful but takes on a somewhat grotesque quality as well as Hà compares the fruit to human body parts: “five papayas the size of my head,/ a knee,/ two elbows, / and a thumb/ cling to the trunk.” There is also a sense here of Hà’s pull towards the familiar, the home and a life she knows, although this life may be quickly taken away. This is further seen in the image of the papaya being eaten: “Black seeds spill/ like clusters of eyes, / wet and crying.”

Once Hà is on the ship to America, the papaya fruit calls to her, and she longs for the fruit as much as home itself: “The first hot bite/ of freshly cooked rice, / plump and nutty, / makes me imagine / the taste of ripe papaya / although one has nothing / to do with the other.”

Once in America, Hà experiences all sorts of challenges, and the fruit is not mentioned for over a hundred pages. But by the end of the book, Hà’s longing for the faraway papaya returns; she compares her desire for the fruit to her mother’s longing for her father. Then, when her tutor finds out how much Hà misses papaya (Hà points to a picture of the papaya tree and describes the fruit hanging “in the full sun, / showing off a bundle / of fat orange piglets”), the tutor gives Hà some dried papaya as a present. At first Hà is so disappointed and angry at the difference in texture between the ripe and the dried fruit, she throws it in the trash! But in the middle of the night Hà has an idea: She retrieves the fruit and wets it to give it a more familiar taste:

The sugar has melted off

leaving

plump

moist

chewy

bites.

Hummm . . .

Not the same,

but not bad

at all.

Philomel Books, June 2015.

The reader understands—through Hà’s interaction with the papaya—that Hà has accepted her life in America although it will never be the life she had in Vietnam. Readers close the book knowing Hà will be okay.

In verse novels, unlike standard poetry, the author has the opportunity to weave imagery into plot AND, what’s more, to illuminate character change and development through image. There is a back-and-forth dialogue between the language and the plot that, if done well, can create such a satisfying, emotionally poignant story. This is certainly the case in Thanhha Lai’s book.

The key is to create an image system that is organic to the character herself as well as to the story. In SKYSCRAPING I chose celestial imagery, and in two other projects I used water and plant/food imagery to reflect the main character’s emotional state. In all of these cases the image system is also related to the plot itself. In SKYSCRAPING, Mira takes an astronomy class, and the starlessness of New York City becomes a metaphor for her feelings toward her parents’ and their betrayal. In another projects, the main character is from Myrtle Beach, so water is a big part of the way she sees the world and the cathartic climax of the book involves a freshwater creek. In another project, a novel in vignettes, food foraging is central to the plot and the plant imagery works with this point. But it is the challenge of how to create metaphors in these worlds as they relate to human psychology that I find enticing and, honestly, just fun. There’s an exercise I do with my students where I ask them to close their eyes, go back in time to the age of their character and look around. What do they see around them that might reflect their character’s emotional state? Can they find an identity crisis in an image outside the character’s window? Can they find a way for that character to sense her relationships changing as she engages in her environment?

Image systems are about showing the reader a new way to look at the world, but they can also add a layer of depth to your writing by helping you convey to your reader a character’s growth and evolution. Verse novels are a challenging form—the language and the narrative can fight each other for dominance—but in the case of image construction in particular, they can also work together to create something stronger than either one alone.

Cordelia Jensen.

Cordelia Jensen was Poet Laureate of Perry County in 2006 & 2007. She graduated with a MFA in Writing for Children & Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Cordelia’s YA Novel in Verse, SKYSCRAPING, is forthcoming from Philomel/Penguin in June 2015. Cordelia teaches creative writing in Philadelphia, where she lives with her husband and children. Cordelia is represented by Sara Crowe of Harvey Klinger, Inc. You can find her at www.cordeliajensen.com and on Twitter @cordeliajensen

April 17, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Abigail Friedman: Translating Momoko

On March 11, 2011, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan struck the northeast coast of the country’s main island. The tsunami that followed reached heights of up to 133 feet, slamming into fishing villages along the coast, dragging and swallowing into the sea everyone and everything in its wake. Over 15,800 people died as a result of the earthquake and tsunami; another 2,584 are still missing.

Stone Bridge Press, October 2014.

The tsunami flooded several reactors at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, jamming the emergency generators needed to keep the reactors from overheating and producing a nuclear meltdown. In all, more than 342,000 people were evacuated from the area surrounding the reactors and from villages devastated by the earthquake and tsunami. An entire region of Japan that was once populated is now off-limits because of radioactivity.

In I WAIT FOR THE MOON: 100 Haiku of Momoko Kuroda (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2014), I translate several of contemporary haiku master Momoko Kuroda’s haiku inspired by this tragedy:

deep beneath the sea

upon those in deepest sleep

cherry blossom petals fall

wild east wind –

an old woman heads

toward unfamiliar streets

Momoko Kuroda.

Although Momoko is tremendously well-known in Japan, winning all of the major haiku awards and authoring more than twenty works on haiku including 6 collections of her own poetry, her work has only rarely been published in the west. I WAIT FOR THE MOON is the first book in English devoted entirely to Momoko’s haiku.

Momoko is probably best known for her cherry blossom pilgrimages. She began visiting Japan’s famous cherry trees while she was still working full-time at the Hakuhodo advertising agency. Not wishing to stand out in her company, she kept her haiku pilgrimages to herself initially, taking time off here and there, finding time on weekends and holidays to visit the trees.

flowers must be opening —

in the pre-dawn darkness

the tinkling of a bell

Her pilgrimages soon expanded to other spiritually important sites, encouraged by her meeting with Japan’s most famous Buddhist nun, Setouchi Jakuchō. In the following haiku, composed at Mt. Kōya, Momoko witnesses the ceremony for the passing of the historical Buddha into a state of Nirvana,

the shape of fire

the shape of chanting voices —

Nirvana vigil

All through the icy cold, mid-February night, hundreds of monks have gathered at the main temple and chant verses from the sutras. Momoko, along with other visitors, is seated in a room just off of where the monks are chanting. The sliding doors have been opened to allow visitors the closest possible view. A fire has been lit in the irori or traditional sunken hearth, warming the visitors somewhat.

melting snow —

through a freezing night

chants of praise

Stone Bridge Press, May 2006.

Translation is never an easy task, and translating poetry is even more difficult. I was fortunate, though, in having the strong support of Momoko Kuroda herself in this project. I first met Momoko over a decade ago, when I was living in Japan. In an earlier book, THE HAIKU APPRENTICE: Memoirs of Writing Poetry in Japan (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2006), I describe how a chance encounter with an amateur haiku poet led me to join a haiku group led by Momoko. At the time, I was living in Japan as an American diplomat and had only just become interested in haiku. I had never heard of a haiku group, never heard of Momoko Kuroda, and until then I had never even composed haiku. But my curiosity led me not only to join the group which met near Mt. Fuji, but to ask Momoko if she might also meet with me privately and teach me more about haiku. Over the years, I have come to know her well, and this helped me both in understanding the context of many of her haiku, and in selecting which of her over 6,000 published poems to translate.

my heart’s desire

a woman pilgrim

at long last!

the glow of fireflies —

the ink bottle my older brother

left behind

Abigail Friedman. (Photo by Kuroda Katsuo.)

Abigail Friedman is a U.S. diplomat and published haiku poet who lived and worked in Japan for a total of eight years between 1986 and 2003. She began composing and translating haiku in 2001 as the only non-Japanese member of a haiku group that met at the foot of Mt. Fuji, an experience that formed the basis of her book THE HAIKU APPRENTICE: Memoirs of Writing Poetry in Japan (Stone Bridge Press, 2006). She is founder of Quebec City’s first French/English bilingual haiku group and has won numerous awards for poetry, including first prize in the 2014 annual Mainichi Shimbun international haiku contest and grand prize, 2011 Yamanashi Mt. Fuji haiku contest. She is a member of the Haiku Society of America and Haiku Canada. Her haiku, haibun, and writings on haiku have been featured in poetry publications in the U.S., Canada, France, and Japan, including Frogpond, AOI, The Asahi Weekly, and Association Francophone de Haiku (AFH)