E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 10

April 6, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Cindy Rodriguez: On Emily, Poetry, and My Writing Journey

Emily Dickinson once said of poetry:

“If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.”

Emily Dickinson.

When I was a student at the University of Connecticut, I might have read this quote and agreed with Dickinson, but not in a deep, head-nodding, “I totally understand you ED,” kind of way. I would have read this to mean it was painful.

I have always been a writer and an avid reader. At UConn, I double-majored in English and journalism. I was a word person, but poetry both intimidated and awed me.

Maybe my abstract thinking hadn’t fully developed yet. I entered college at 16, and while I was always a good student, in hindsight, I wasn’t entirely ready for some things. Poetry, I think, was one of them. During an upper-level English class entirely about poetry, I often massaged stress headaches and stared intently at my book or notes when the teacher scanned the room, looking for someone to answer his question. I didn’t feel confident that I could offer comments like my classmates, whose interpretations beautifully unraveled the poem’s figurative language. My end of semester grade was a hard-fought B-. Not bad, but school was usually easy for me. In this class, I felt like I was out of my league.

This is probably why, for many years after this class, I didn’t read much poetry, and I certainly never wrote it. Years later, when I became a middle school teacher, I created a killer poetry unit. I always understood its value and admired those who could capture the beauty and pain of the world in a few words, but I could never do it. Each year, my students blew me away with the poems they created.

This is part of a 7th grader’s poem created after going outside and observing an ominous sky:

The sky is an ocean, an endless boundless sea,

A stormy sea of white-capped waves.

The front is an endless line sweeping across the sky.

A low-flying plane is a seagull struggling against the wind.

The waves froth back and forth, rocking the boat that is me.

Here’s another part of a poem created based on an award-winning photograph:

The tears roll down

His dirty cheeks,

Like a rainstorm soaking

The stark parched desert

Beautiful, right?

That time of year, without question, was my favorite, and it was often my students’ favorite, too, based on a year-end survey they completed for me.

Bloomsbury USA Childrens, February 2010.

But, did I ever write along with them? Nope. Poetry still stirred feelings of intimidation and awe. Poetry for me was something to worship but not practice.

Years later, I started working on my master’s degree at Central Connecticut State University. There, I decided to take an author-centered class about Emily Dickinson. A strange choice, you might think, for a person with a long history of fear and fascination for poetry. But, maybe that’s exactly why I chose this class, even knowing it required three 20-page papers. It was a challenge, and I’ve always pushed myself in school and work. Plus, maybe it was time to redeem myself after stumbling through that undergraduate poetry class. Maybe it was my way of saying, “Let’s go, poetry. Meet me in the parking lot. You and I are going to work this out once and for all.”

And work it out we did. In fact, we became good friends, all because of Emily Dickinson and a great professor who led me through close reading exercises that explored multiple meanings for single words, which meant multiple meanings for lines, and stanzas, and entire poems. Along the way, poetry went from being this superior, untouchable goddess who only mingled with people who “got” her (not me), to being an interesting puzzle that, once solved, could be turned slightly or flipped upside down and it would reveal something else entirely.

And this time around, my reaction to that—to multiple interpretations of the same poem—was not to think that I was wrong, that I wasn’t smart enough, but to think, “Wow!” I mean, how entirely amazing that three people could read a Dickinson poem and analyze it as a whole and in parts, down to the individual words, and one of us said it was about taking risks, and another thought it was about death, and the third said it was about the restrictions placed on women in the late 1800s. And none of us were wrong because how we got there made sense, and while there may be scholars who have determined certain poems mean certain things, in that class, we were validated. We were exploring literature and its possibilities. We weren’t hunting for the one right answer.

When I was younger, in that poetry class, I wanted to be right, and the answer wasn’t obvious. It never is with poetry. I wasn’t allowing the words to chill me to the bone or make me feel like my brain was exposed to the world. I was trying to interpret poems like I solved math equations.

After that graduate course, I started to plan what would eventually become WHEN REASON BREAKS, my debut young adult novel about teen depression, attempted suicide, and Emily Dickinson. Her life and poetry heavily influence the story, and I even wrote a poem for one of the chapters in the voice of one of the main characters, Elizabeth Davis. It took me as long to craft that one poem as it did to write an entire chapter, so I’m definitely not claiming to be a poet. But I will say that my relationship with poetry has changed thanks to Emily Dickinson.

Poetry still intimidates and awes me, but in the best possible ways. I admire writers who create single poems or entire novels in verse, using carefully selected words to invoke images, characters, stories, and emotions. And while novelists do this, too, a poet’s economic use of language impresses me every time. So, yes, I remain awed by poets and what they do. Much of WHEN REASON BREAKS expresses my appreciation for poetry in general and for Emily Dickinson in particular. I still see poetry as a powerful goddess, but now I don’t consider her to be untouchable. In fact, we hang out all the time, and she’s so cool, no fire can warm me.

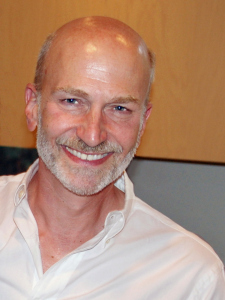

Cindy L. Rodriguez.

Cindy L. Rodriguez is a former newspaper reporter turned public school teacher. She now teaches as a reading specialist at a Connecticut middle school but previously worked for the Hartford Courant and the Boston Globe. She and her young daughter live in Plainville, Connecticut. WHEN REASON BREAKS is her debut novel. Visit her on Twitter @RodriguezCindyL.

April 5, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Terry Truman: What Poetry Can Be

I started my career in writing as a poet a long time ago. It was an excellent way to NOT make any money but also to cut my teeth on the significance of language and the striving for perfection. The written word has a certain magic to it whether we are trying to make magic or not; people tend to give a conscious or unconscious gravitas to something they must take the time to read.

HarperCollins, June 200.

But so much poetry for so many decades felt like acrobatic word games and sho-offy stuff to me. I often couldn’t understand what the poets were even trying to say. Modern poetry, and I personally believe Bukowski had a big influence on this change of direction, has become more accessible and direct. ‘Meaning’ isn’t hidden any longer and younger, modern poets are not afraid to say, very directly what they feel they need and want to say.

My poetry now is much more direct and I am much less worried about someone saying, “Oh, that’s just chopped-up prose.”

To which I would likely respond with “So what?” or “bleep-bleep” depending on my mood at that moment (I enjoy using expletives, curses, profanity and the like quite a bit for their power at driving home the passion of my point–kind of like a series of exclamation points !!!!! at the end of a sentence, but hopefully a little less histrionic).

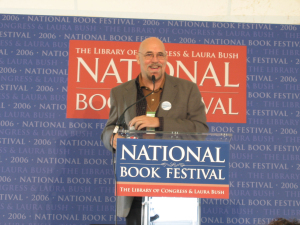

Terry speaking at the National Book Festival.

There has come with my age and advancing years a freedom of both language and subject matter, which makes me resent death, because I’ll likely run out of time before I run out of things I want to write poems about. Because I have a little more space here, below is a poem I like quite a lot and one suitable for kids/teens, which not all my ‘bleeping’ poems ‘bleeping’ are these days!!!!!!!

Guardian at the Gate

Our dog, Rusty

60 lbs

of mixed breed,

partly

German Shepherd,

Collie,

Belgian Malinois,

who knows for sure, his breeding?

He Parks

at the upstairs

front window

of our townhouse

and growls

low

and deep, every time

anyone walks by

on the sidewalk outside.

If it’s Patti

or me

arriving back home

he doesn’t growl,

he stares at us until he’s

sure who we are, then

he leaps up

on his arthritic

shoulders

and throws himself

down the stairs

to greet us,

(As a friend once said

“He’s like livin’

with a ‘bleepin’ kangaroo!”).

But when anyone else

approaches

our front door,

from grocery delivery

to the UPS guy,

Rusty’s growl turns into

a single bark, just one:

loud, deep,

throaty and threatening—

A one-time warning

that if you come through that door

be prepared

because

you’ve gotten all the

heads-up you’re going to get.

We picked him up

at an animal shelter

90 miles away.

Got him back to our house,

opened the door of our pick-up truck

and he took off.

Ran himself stupid

and muddy for 4 hours

up on the prairie,

until he finally

jumped back into the truck.

He’s never left our sides

since.

He’s nipped a few

people foolish

enough

to reach

towards Patti,

and he’s

never run from

anything,

especially things that scare him.

On the ‘fight or flight’ continuum

score it,

Flight: 0

Fight: All you’d ever want.

Greatest dog I’ve ever had,

and that’s saying something,

our Guardian at the Gate.

Terry Truman.

Terry Trueman is best known as the author of numerous fictional works, both novels and short stories, marketed for teens, the best known of these, his novel STUCK IN NEUTRAL which was a Printz Honor Book in 2001. Trueman has traveled to virtually every state in the USA talking about writing and reading. His first love has always been poetry.

April 4, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Jason Carney: Breath, Body, and the Living Poem

“…The audience is usually made up of young people, which means that this is not a custom that is dying out— as prophets of the end of poetry maintain—but a living tradition, one that is being taken up and renewed.” —Octavio Paz

Octavio Paz.

The living tradition that Octavio Paz wrote about is not the act of reading the poem aloud from a page or reciting what you have memorized, but rather the unity of poet and poem, an utterance from the soul of the author. A poetic message birthed in necessity and resistance. A spiritual moment of spontaneity that connects the artist with the audience, in which the higher-self of the artist is alive far from the limitations of mortality that flaw the consciousness of the lower-self.

Nowhere has the art of the oral poem been more cultivated over the last twenty-five years than the poetry slam. Two very important factors have really fostered this development. First, the fact that poets are under a time limit of three minutes creates a sense of urgency pushing the poet to evoke not only a clarity of their work, but also a desired response of that work from the audience. Second, the heightened sensory elements of competition give poets a chance to live in the space given. A packed room containing a boisterous audience, especially when placed in a national competition, generates an aura of energy that permeates every surface of the venue.

The poet must harness the energy swirling through the crowd. They must focus the energy that the onlookers not only give, but also receive from the poet and their work. The ability to feel the energy of the space and to have awareness of the give and take of that energy is of paramount importance to the poet. A live body exists within the internal happenings, but also the external circumstances.

The breath (living moment) of the poem must have a body balanced in between, an open valve, a conduit that carries the conviction of the art. When done correctly the poem is an effortless communication, from the beginning of the motion it is fluid and natural. This living moment of spontaneous creation is what I call the breath of the poem. This developing delivery from the whole of oneself is the voice of our modern times.

In all its incarnations—high school slams, collegiate slams, or in the adult venues—you will find on the slam’s local, regional, and national stages, poets have pushed the boundaries of communication and breath. The slam community is discovering ways of delivering the poem from the core of the body beyond the inanimate limitations of the page; and by so doing constructing works that culminate in a unity at its highest expressions between the audience, the poet, and the poem.

A fluid movement of energy, in which, the eternal act of creation becomes a living entity of the mortal instant. The present becomes the fragile thread binding the poem’s breath. The artist, disconnected from the lower self, appears to be a conduit more than a source. Even in the silence of the poem, a harmony of energies exists filling the air around the poet.

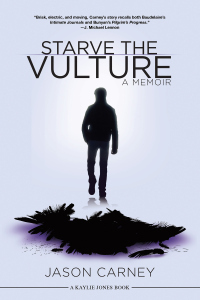

Kaylie Jones Books, January 2015.

To experience, a poet who reads the meter of their poem or the cadence of the syllables as the focal point of delivery is often flat and without emotion. In that thinking, the form is more important than the breath of the poem. As if, the boundaries of their creativity are the two-dimensional confines of white space. These poets deny the natural home of the poem, the body. Even worse if their own work is not an ingested expression; this often will leave the audience feeling like this is the first time the poet has ever seen the poem. Why would an artist expend so much care and energy to create a work, if they do not intend to put care and energy to the re-creation of that work?

A poet should be natural and fluid on the stage. That transcendent moment is where the higher self of the artist is the vehicle for the art that is being received by those it touches. There are two ways of receiving or acknowledging something as truth—with your head and with your heart. Art has the possibility to stir one or none of these receptors. At its highest level, art can cause one to awaken the other creating enlightenment for whoever is receiving the art. The live performance of the poem not only offers this transcendent moment for the audience, but also for the poet. This only occurs if the breath of the poem is fluid, natural, and located firmly within the poet’s body.

I can best describe what slam poets search for in the coming together of the craft of writing and craft of performance to where the body and the poem are one— seemingly outside the constraints of time, living in a present moment. The recitation of poetry during a slam is an unrepeatable movement of time where the magical becomes possible. A genuine soulful utterance brought to life from the truest part of the artist.

In other words, the poem is alive. To create a living thing, not just the mere audible sounds of words spoken in real time, one must be one grounded in the body. All art is spiritual in nature, to think of your writing in lesser terms, I feel, speaks to the lower self. While the human artist is very flawed, the energy of creation that uses the artist is flawless. When an artist can tap into this energy and connect with the higher self, the poem ceases to be limited.

Jason Carney.

Jason Carney, a poet, writer, and educator from Dallas, is a four-time National Poetry Slam finalist and was honored as a Legend of the Slam in 2007. He appeared on three seasons of the HBO television series Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry. Carney has performed and lectured at many colleges and universities as well as high schools and juvenile detention centers from California to Maine. STARVE THE VULTURE is his memoir.

April 3, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Calef Brown: The How and Why of Wordplay

Happy Poetry Month!

I’d like to talk a little bit about the “how” and the “why” of my poetry.

Henry Holt and Co., March 2015.

I come from a family that has always loved wordplay – my parents, siblings, nieces and nephews, and grandparents. We all love music as well, and for me, growing up, that tie to the musicality of language was part of what inspired me to write. My father loved poetry – he studied with Pulitzer prize winning poet Robert Coffin in college and would frequently recite poetry from memory. When I was very young I vividly remember my mother reciting bits of nonsense – one of my favorites being:

Algy met a bear.

The bear met Algy.

The bear was bulgy.

The bulge was Algy.

The playfully dark edge to that poem is something I’ve always loved, and that aesthetic has stayed with me.

I also clearly remember my older brother reading Beatrix Potter’s Two Bad Mice to me when I was 5 or 6 , and just hearing the name “Hunca Munca” repeated made me laugh so hard that on one occasion I literally peed my pants.

That particular reaction to a funny bit of language hasn’t happened since, although, as they say, never say never.

I have become known for writing humorous verse, but not all of my poems are meant to be ha-ha funny. Some are absurd, surreal, quizzical, or evocative and atmospheric. My poem Orchids, for example is about discovering hidden beauty.

Orchids

Orchids are awesome.

Incredibly so.

They steadily grow,

deep in the forest

where the tourists

and the florists

never go.

The idea that words can be elastic, musical, and communicate beyond their literal meaning is something that I loved as a kid, and am still enthralled by today.

I have a poem called Oilcloth Tablecloth that was inspired by overhearing someone at a flea market asking a vendor if they had any of the aforementioned items. Those words – two syllable-three syllable, a little backbeat – just stuck in my head . Later on they became the root of a poem. If a genie ever grants me three wishes, one of them might be to hear Tom Waits read this one:

Oilcloth Tablecloth

Oilcloth Tablecloth

keeps the table dry,

despite the many soda spills

and coffee gone awry.

If someone sloshes orange juice

or baby starts to cry,

Oilcloth Tablecloth

keeps the table dry.

HMH Books for Young Readers, September 2010.

I love the process of building a poem, to me it’s like searching for, and collecting, the pieces to a puzzle that keeps shifting and changing as you go about assembling it.

A poem from my collection HALLOWILLOWEEN titled The Vumpire began with simply noting the similarity between the words vampire and umpire, then finding and following connections. Are there words and concepts that link these two characters? Well, of course there’s the bat, and bats often shatter in pro ball creating shards that wooden stake-phobic vampires would not be pleased with. There’s the dugout , and graves are dug out. A vampire, it would seem, would enjoy a nap there during the seventh inning stretch. Baseball has night games, and so on….

The Vumpire

He only works night games.

His signals are creepy.

When managers argue,

he makes them feel sleepy.

He never appears

in the photos we snap.

A widow’s peak peeks out

from under his cap

when he takes a nap

in the dugout.

His eyes bug out

and he hisses like a frightened cat

at the sight of a broken bat.

How weird is that?

Once, while waiting on deck,

I caught him staring

at the back of the catcher’s neck.

Weatherbee’s Diner was inspired by my mother’s fondness for using the expression “cook up a storm”, especially around the holidays. So I made lists of all the wonderful terms for weather phenomena and looked for relationships to food. Creating lists and word maps is one of the ways that helps me take a germ of an idea into something more.

Weatherbee’s Diner

Whenever you’re looking for something to eat,

Weatherbee’s Diner is just down the street.

Start off your meal with a bottle of rain.

Fog on the glass is imported from Maine.

The thunder is wonderful, order it loud,

with sun-dried tornado on top of a cloud.

Hurricane Curry is also a treat.

It’s loaded with lightning and slathered in sleet.

Cyclones with hailstones are great for dessert,

but have only one or your belly will hurt.

Regardless of whether it’s chilly or warm,

at Weatherbee’s Diner they cook up a storm!

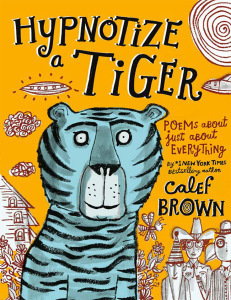

Here are few examples of poems and their origins from my new book HYPNOTIZE A TIGER: Poems About Just About Everything:

Somewhere in my daily reading/internet time-wasting I came across a reference to a Kodiak Bear. I saw the word “Kodak” in there, and that lead to the poem Camera Bear:

Camera Bear

Very shy, and extremely rare,

the Massachusetts Camera Bear

stays aware of the local area

through landscape photography.

It shoots the hillsides,

charts the topography,

then posts pictures on a blog–

shots of the cranberry bog,

the best log for back scratching,

and where to find picnickers

(mainly for snack snatching).

Speaking of time-wasting, while channel surfing in a hotel room (the only place I tend to watch lots of TV) I heard the snippet “an ice road trucker” which sounds the same as “ a nice road trucker”, but is pretty much the opposite, so….

A Nice Road Trucker

I’m a Nice Road Trucker.

My handle is Wayne.

My favorite route to travel

is a country lane.

Turnpikes and traffic

are bad for the brain.

Me and a freeway?

Never the twain.

Scenery is key for me–

it keeps me sane.

Driving over mountains

in a misty rain.

Find me out in Cali

or the coast of Maine.

I’m a Nice Road Trucker.

My handle is Wayne.

HMH Books for Young Readers, January 2013.

Most of the time, however, the ideas come from my back-and-forth writing and drawing process. Really, my main strategy is just to try to be mindful and curious. To stay aware of sounds and sights around me in my daily life, and write and draw in my sketchbooks as much as I can. Sometimes a poem begins with a drawing, often of a character, and then I start to write a poem about that person or creature. Other times I will do some free associative writing in a sketchbook for a set period of time, put as much down as I can, then later go back to it in a different frame of mind and look for ideas, places to start.

This one, in the Schoolishness chapter of HYPNOTIZE A TIGER, began with two words – “grim creatures” that popped up in some free-associative writing. I noted that it rhymed with “gym teachers” and was off to the races…

The Gym Teachers

They do not, ordinarily,

have pointy teeth of enormous size

and scary greenish eyes,

so my classmates and I

were rather surprised

by the ghoulish faces and glum features.

Something is wrong with the gym teachers!

They crouch in the bleachers

like sneaker-clad sand fleas.

Their whistles are deafening–

louder than banshees

on a noise spree.

Here’s what annoys me:

They make us do battle

In long games of “dodgebull.”

(With actual cattle – a giant garage full!)

Do we look like matadors?!

To them, it doesn’t matter, of course,

having been possessed, I would guess,

by some sort of beast-nest,

or a throng of Brothers Grimm creatures.

Something is wrong with the gym teachers!

HMH Books for Young Readers, April 2006.

In writing poems that will hopefully spark kids imaginations and inspire creativity, I try to stick with subject matter that they can relate to. Food. Family. Creatures – from monsters to insects to family pets. School, Friendship, Play. As I mentioned before, I’m known for humor and nonsense, but most of the time I don’t necessarily set out to create a poem that will be funny. Yes, in the course of writing, I do crack myself up from time to time, and once in a while it’s to the point of manic giggling (which usually stops abruptly when I realize that my family downstairs probably can hear me) but once I have the germ of an idea I get pulled into the activity of creating the perfect expression of it, with not one unnecessary word or even syllable. Craft is extremely important to me. It’s a pleasurable but challenging process of problem solving, that, since my poems are meant to be read aloud, is not unlike creating a song.

So, as I’m writing a poem I’ll also speak it, and sometimes sing it (if no one is around). I often have the speech function of my computer read my poems in-progress just to hear them in a voice other than my own – even if it’s a robotic one.

I also try to build inspiration and opportunities for inspiring wordplay into my illustrations. There’s a poem called Ten-Cent Haiku in my book FLAMINGOS ON THE ROOF:

Ten-Cent Haiku

I sat down to write a haiku.

It seemed like the right thing to do.

I wouldn’t need very much time.

No need to bother

with making it rhyme.

I reached in my pocket

and pulled out a dime.

This is my ten-cent haiku:

Shiny silver friend.

I will never let you go.

Look! An ice cream truck!

In the background of the illustration, on a lawn in a park, there’s a dog who is sitting with rapt attention focused on a tennis ball, echoing the man who is contemplating the dime in his hand and composing his haiku. When I recite this one, and show the illustration during school visits, I ask the kids to think of a haiku that the dog might be dreaming up as an homage to the ball– his beloved plaything. Here is my favorite of the haikus created by students in response to that prompt:

I want that great ball.

Someone give me that great ball.

I needs my slobber.

There is a chapter of poems that contain portmanteaus in my new book and I’m looking forward to integrating them into both my school presentations and workshops. Perhaps students can make portmanteaus with more than two words –three, four, five, then incorporate them into a poem. Maybe draw them. What other ways could they create links, and combine words, or pictures or ideas?

Over the years, I have visited many schools, and drawn so much inspiration from the enthusiasm and creative energy of the students.

HMH Books for Young Readers, March 1998.

I’ve also learned a lot from the ways kids react – or don’t– to specific poems and illustrations. I am always surprised and delighted too, by the questions they ask, and their incredibly creative ideas and writing that come out of workshops and classroom visits. I enjoy working with a range of grade-levels –from kindergarten up to fifth and sixth . It’s challenging to craft presentations and workshops that are appropriate for different ages, but I feel I have poems and books to draw from that cover that range well. I’m especially looking forward to bringing my new book to middle-grade students, it’s my first created with that audience especially in mind.

There are so many special moments from school trips that I will never forget. During a visit to a school in Portland, a teacher told me about a particular first-grader who was really struggling – especially with reading and issues around self-esteem. After I did a presentation, the students went back to their classrooms and did an exercise which stems from a book I illustrated called Greece! Rome! Monsters!.

During my presentation I had discussed mythical creatures made from combinations of animals – Griffins, Basilisks, Chimeras and the like, then asked students to create their own hybrid animal, make a drawing, and write a poem about it. It could rhyme, or not, be silly, scary, or serious. As the teacher related it, back in the classroom this student did a drawing of an elephant-snail and wrote an accompanying six-line poem. He then stood up on his chair, threw his hands up in the air Rocky-style, and shouted “I’m a poet!!!!”At the end of the day I met with him and he proudly showed me the drawing and read the poem. As someone who had his fair share of struggles in elementary school, That experience brought tears to my eyes. I always try to give as much as I can in my visits, but always leave feeling that I got back more.

This brings me back to the “why” of what I do. Over the years I have received so many letters and emails from parents relating how my books have played a role in their family sharing and creating poetry, or in inspiring children to play with language. I used to memorize nonsense verse when I was young, and I love hearing about kids memorizing my poems and creating their own spin-offs, working them into plays and puppet shows, or illustrating them. The worlds of picture books and verse are what motivated me to become a writer and artist, and it’s been a profoundly humbling experience to help inspire kids to create their own worlds of poetry and art.

Calef Brown.

Calef Brown is an illustrator, character designer, and children’s book creator. Books he has written and illustrated include POLKABATS AND OCTOPUS SLACKS, HALLOWILLOWEEN, and FLAMINGOS ON THE ROOF, which was a #1 New York Times bestseller. He has also illustrated ADVENTURES OF A CAT-WHISKERED GIRL, THE YGGISEY, and THE NEDDIAD by Daniel Pinkwater and THE CURIOUS CASE OF BENJAMIN BUTTON by F. Scott Fitzgerald. He lives with his family in Vancouver, British Columbia.

April 2, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Jen Brooks: Celebrating Poets in a High School Classroom

“I didn’t know authors could be so funny!” said the high school sophomore to me after four authors I’d brought into our school had finished their presentation.

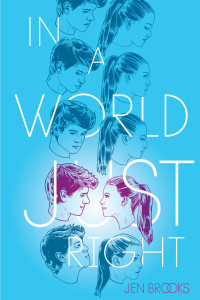

Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, April 2015.

Typical of the kids I used to teach was the attitude that writers somehow aren’t real people, aren’t relevant, aren’t anything more than one-dimensional intellectuals holed up in wood-panelled studies smoking cigars and drinking tea (or wine, or whiskey) while hunched over a keyboard by the light of a candelabra.

This is only a slight exaggeration.

And if novelists are a different species, poets, who write poetry, are from another planet entirely.

There were many things I wanted my students to discover about poetry, but for the purposes of this article, I’m going to present two classroom projects I found taught my kids a thing or two about poets. I don’t mean specific poets like Emily Dickinson or Percy Bysshe Shelley. I mean “people who compose poetry.”

That includes you, me, my students, and Emily and Percy.

Thing #1: Poets often write about the same subject as other poets, the same subject you might write about.

Thing #2: Part of the awesomeness of poetry is that the same subject can be addressed with wild variety stemming from wildly different points of view. Part of the joy of poetry is to see that subject addressed in a way you wouldn’t have thought of yourself, so you come away with a new way of looking at that subject. Conversely, part of the joy of poetry is recognizing in someone else’s treatment of a subject a commonality with your own thinking, and in a world where it can seem no one else understands you (especially if you are an adolescent), such resonance is affirming.

PERFORMING A NATURE POEM CIRCLE

This classroom project began with a circle of desks. In the center I would strew a collection of photographs ripped from day planners, most of which depicted nature scenes. The landscapes varied from mundane to exotic, close-up to wide-angle, summer to fall to winter to spring. Students would each choose a picture and bring it back to their desk, on which would sit nothing but the picture, a piece of lined paper, and a pen.

Emily Dickinson.

I’d ask each student to make an observation about their picture and write it on the first line of the paper: “There’s a snow-covered tree that still has its yellow foliage.” “There’s a bright blue waterfall in a canyon.” “There are red berries near a rock.”

Next, leaving their picture and their paper behind, the students would get up and shift to the seat on their left. I would ask them to record an observation about the new picture in front of them, but require that it not repeat the line already there.

We’d shift chairs for three or four pictures before I’d add directions. The next switch might require them to phrase their observation in the form of a simile. The next might require a metaphor. The next might use personification. Alliteration. Onomatopoeia. Hyperbole. The only consistent requirement would be that the students must read all of the observations that came before so as not to repeat. By the end of the activity, the students would have to make some pretty unique or unusual observations in order to meet that requirement.

The fun part of this activity was returning to your original picture to see all of the things others had written about it. Some people would write very dramatic observations. Others went out of their way to be funny. I would tell the students to pick eight lines that they liked best and copy them over on a separate piece of paper in an order that made sense to them. Then we’d read these “poems” aloud and get some satisfaction out of hearing if any lines we wrote got picked.

Homework was to take the eight lines and edit as desired. This could mean cutting lines, adding lines, changing the order, changing the wording within lines, or scrapping the whole thing and keeping one central idea from one line.

The next day we would share the new drafts, remembering what they had been the day before, and appreciating the directions taken. Discussion always touched upon how the variation in the lines written by others the day before—whether in detail, tone, or phrasing—contributed to the success of the draft.

WRITING LOVE POETRY WITH HIGH SCHOOL SENIORS

This project would begin on the internet. A quick search for “love poetry” yielded multiple sites to explore, and I would pick one where regular people were invited to post their own love poetry. Students were asked to print off a poem from the site to bring to class.

Emily Brontë.

They were also asked to print off the lyrics to a song about love.

In class we would discuss everyone’s two chosen love poems. We would look for general classifications for their poems like “unrequited love,” “lost love,” “falling in love,” “perfect love,” “unhealthy love,” “love poems about something other than love,” etc.

With an idea of the different ways love can be approached, we embarked on a fairly standard survey of love poetry from the British literary periods outlined in the textbook. Poems included:

“Alisoun” –Anonymous, Middle English verse

“The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” –Christopher Marlowe

“The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd” –Sir Walter Raleigh

“Sonnet 18” –William Shakespeare

“Song, To Cecelia” –Ben Jonson

“Love Armed” —Aphra Behn

“Bright Star” –John Keats

“She Walks in Beauty” –George Gordon, Lord Byron

“My Last Duchess” —Robert Browning

“Sonnet 43” —Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“Remembrance”—Emily Brontë

“When I was One and Twenty” —A.E. Housman

“Adam’s Curse” –William Butler Yeats

“Happy Ending” –Fleur Adcock

Then the fun part! Each student wrote their own love poem. If you’ve ever taught in a high school classroom, you know how awkward this might be!

We would begin the sharing process by posting our poems on the walls around the room—anonymously. Then we would go around and read them, surely making guesses as to who wrote which poem. Then we would circle up and reveal identities and discuss where the poems fell in the different categories, which poems inspired the students’ originals, what artistic choices were made, and what lines really resonated or were particularly effective.

My students always surprised me. Quiet ones would write with hilarious humor. Loud ones considered class clowns would write something swoony or sweet. By the end of it all, between looking at the public poems from the internet, the song lyrics, the canonical poets, and the students’ own work, the students would definitely have an appreciation for the multitude of ways a common topic could be addressed.

As a bonus afterward, we made a giant love poetry display on the wall outside the cafeteria. In a group cooperative effort, students creatively arranged their own poems along with the internet/lyric/canon poems in one giant collage. (With hearts and other relevant art, of course!)

Activities like the above really helped my students imagine poets liberated from their stuffy writing rooms. They could imagine meeting them in the street, or sitting the next table over in a restaurant, or talking about the latest movie releases or top twenty hits.

In other words, poets became people, just like my students or you or me. More importantly it was okay for my students to be both people and poets!

Jen Brooks.

After graduating from Dartmouth College, Jen Brooks taught high school English for fourteen years. She holds an MA and MFA in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University. Her debut YA fantasy, IN A WORLD JUST RIGHT, features several scenes in a creative writing classroom, and poems written by her hero and heroine factor into key moments of their personal journeys. When she’s not writing in her office overlooking her back yard pond, you can find her running, hiking, visiting national parks, or going out for ice cream with her husband and son.

April 1, 2015

National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Michael J. Rosen: Writing On Ice

Writing on Ice

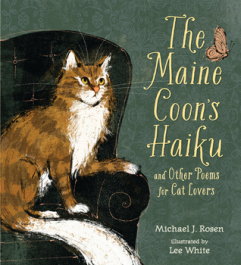

With the recent publication of THE MAINE COON’S HAIKU AND OTHER POEMS FOR CAT LOVERS, the third volume in a series of books that culls poems from my ongoing practice of writing haiku, I pulled together these fragments, these reflections, for National Poetry Month. Also included: half a dozen haiku that were written this winter that are not a part of the book. Many thanks, EKA, for the invitation to share this!

Turning Visible

Candlewick Press, March 2015.

How quickly, without our even realizing it, something remarkable becomes routine. Novelty turns invisible. Something that once grabbed the attention (and that’s the right verb! Something grabs, seizes, plucks our awareness from a lulled or impatient inventory of the present), eventually, all too quickly, loses its grip. Once we can recognize or expect that formerly-arresting something, our senses check it off the life list and listlessly go about their business until the next something interrupts that maundering. They idle until we consciously shift them into gear again.

In terms of survival, there’s a positive rationale for this. It behooves every species to quickly evaluate dangers and threats, and then to cease focusing on those that are neither likely nor imminent. Likewise, our human brains can’t consciously enumerate or name or respond to every stimulation the senses present every waking instant; we learn to attend to the essentials as well as tune out the inessentials. For better and worse, our minds become inured and dismissive; our emotions turn callous; our senses wear blinders, or their sensitivity wears out.

So it requires a deliberateness, a retraining of sorts, in order to open our consciousness to the familiar. To be patient enough with the commonplace to find the exceptional nuances that often afford even more pleasure than something wholly or newly remarkable. I say “even more” because, while the unfamiliar affords the pleasure of surprise, the familiar— one refreshed, once encountered with genuine openness—affords both the pleasure of recognition and that of surprise.

A practice of haiku can be the practice of turning the familiar visible again. Of removing the “over” from “overlooked.” Of refusing to let “over and over” govern your watch.

The Importance of Being There

Last summer, I went to a mind-blowing house concert by a remarkable singer/songwriter. A total of 50 people gathered in a two-story horse barn that had been converted into an inviting performance space and microbrewery. For 90 minutes, the loft reverberated with just one voice and one guitar. On overstuffed coaches, on floor pillows and picnic blankets, no one sat farther than 15 feet away from this powerful singer’s earnest, plaintive, urgent, contagious spirit. The room resounded, shuddered, thrummed, and ached with his soulful, ambitious, acoustic presence.

And a full third of the concert-goers viewed the entire performance on their cell phones. They focused on holding their devices still. They stared at the tiny 2-D face on the screen, rather than the full-size 3-D performer almost within reach. They concentrated on keeping the musician’s body in the center of their screen, on shifting this way or that way when someone in front of them shifted and blocked their camera’s line of sight.

Candlewick Press, September 2011.

For those recording the singer, it seemed more important to have been there, than to actually be there. More significant to have something to share/post of their having been there…than to be immersed, abandoned, open—vulnerable, even—to the power of the performer and his music. They missed the subtle expressions of the singer connected his eyes with listeners’ eyes, modulated his falsetto or ramped up his bellowing notes, or basked in the reverberations of his notes among the 200-year-old rafters. They missed the way the dimming sun flickered patterns against the wall-size fireplace behind the performer.

Maybe they’ll remember more of the concert than I will recall. Certainly they’ll have something with which to remind themselves, assuming the quality of a phone’s recording is really something worth replaying…once, let alone, more than once. They’ll have proof.

But they won’t have vivid memories of actually absorbing, feeling that precise experience. Their eagerness to keep the experience meant they never lost themselves in it.

In 1930, Robert Frost wrote, “Strongly spent is synonymous with kept.” I live by that 85-year-old idea. I believe that “strongly spending” time at a concert—simply (It’s clear that “simply” isn’t all that easy, right?) listening to the man playing and singing—would have been more memorable than the keeping of a recording.

This practice of living in the future tense—what I will do with what is happening now—is antithetical to satisfaction in life. I think our greediness with documenting, with posing and posting, with much of technology’s easy record of here and now, whittles away at the profound pleasure of taking part in what is taking place. And of witnessing. Truly being present—witnessing—is what shapes our character, hones our empathy, and builds our appreciation of and respect for difference.

Seeing Still

I teach a workshop called “Seeing Still.” It’s very much like what most yoga teachers will say at the start of class: Focus on what is happening precisely on your own mat, at this given time. Relinquish thoughts of past performance and future expectation. Ignore the pressing duties and niggling details that stand just outside the studio. So my writing workshop is a session on “sitting still”…but with the mind. It’s a workshop on “standing still,” but with the senses held in place rather than the feet.

Granted, it is difficult not to fidget. It takes practice. But one thing practice makes—one thing that often is eclipsed—is its capacity to afford us pleasure. The pleasure of repetition. Of simply trying hard. Of being willing to try again.

So practice may make perfect, but it always makes us happy.

Writing on Ice

We can walk and never think about our feet. Once we’ve mastered a gait—our first steps as a toddler, the choreography of a few dance moves—our autonomic nervous system ensures that the muscles and nerves are innervated accordingly. Feet are placed correctly, adjusting and advancing without directions from the conscious pilot.

Photo by Michael J. Rosen

But we can commandeer most of those actions. Voluntarily, we can step more quickly, plant our feet farther apart, touch down with the toe first rather than the heel.

This last winter, hiking with my dog on our snow-covered paths or even leash-walking in the city, my steps outdoors required far too many voluntary actions. While I didn’t need to call out tendons by name, warn one ankle’s tendons to roll with the swiveled joint, order each hip joint to soften or stiffen to keep me from falling, most every step announced itself with a wince or pain, pressure or resistance—or a lack of resistance. My gait was unpredictable, as I gauged the position and pressure to put into each step, as I decided whether to lift above or shuffle through the accumulated snow and ice, as I guessed whether to step lightly, slide, stomp, or stop.

winter, what options

you leave! foot-deep snow or path

of packed-ice boot steps

Photo by Michael J. Rosen.

Likewise, we can converse without really thinking. And we can write that way. My idea of “seeing still” is to persist in the action of seeing, rather than in the inaction of a snap perception. Sustain the observations of a prolonged encounter, rather than opt for a sense of completion and its associated relief.

Let me stick with this winter’s hikes. Writing haiku is much more like walking on ice. It offers some autonomy to the brain that might believe it knows what you’re doing, but it also withholds some control in order to guide the words marching forward with more deliberateness, more choice, more distinction. Writing haiku is placing words in the natural, unnatural manner of taking steps intentionally, voluntarily.

It’s like walking on ice. Thin ice.

Tumbling

Very often, my practice of writing haiku is more like tumbling a few crude gemstones than cutting and polishing one into a single sparkling cabochon. I’m less driven to the destination of a single haiku that’s perfect because such finessing can risk becoming precious. Or maybe sentimental: wrapping up the experience or moment too handily; harrowing too much tone and variation in order to hone that pithiest form. So most of the haiku I keep are saved in variations on a page. Each treads water…somewhere between sinking and swimming.

Again, I look for the pleasure in recognizing something unexpected, in stumbling upon something unpredicted.

Ah

Photo by Michael J. Rosen.

It’s been said that haiku lives on the tip of the tongue. It’s…it’s…not that, but I’ve almost got it—wait! It’s right on the tip of my tongue…. But then it’s never quite uttered. There a tradition to just let a haiku be—simply be. Not be a description. Not be a definition. Not be something that evokes a question or a comment from the reader. Not be an “aha!”…only an “ah….” An expression that might be translated as, “Now, I see it.”

cat’s frozen paw prints

heading the opposite way

in last night’s boot prints

•

this morning’s cat tracks

frozen in last night’s boot tracks

coming and going

•

heading out, I find

cat tracks—frozen in last night’s

book tracks—heading in

Mannix.

A Winter with Cats

As promised, in light of the publication of THE MAINE COON’S HAIKU AND OTHER POEMS FOR CAT LOVERS, here is a sampler of haiku written this winter.

They feature or suggest the cats—Slinky, a mackerel tabby, and Mannix, an orange-and-white Manx—who share my acres.

out in out in out

invisible doors are all

the cats know about

•

eggshell of clear ice

tiptoeing paws skirt the pond—

not breaking silence

•

in fresh sparkling snow

even the cat’s faint pad-prints

cast heavy shadows

•

winter stretches land

across the pond—and cat claims

a sudden acre

•

old snow, it takes you

to remind me how many

travel this same way

Of this last haiku, hewed directly from my very local observations, it didn’t occur to me to think about someone in a city, someone in an utterly different locale, reading it. I grounded the poem in the acres here: I saw the split-hearts of the deer’s hooves, the warm stamp-pads of the cat’s toes, the various point sizes of the bird’s Ys, the “great” tracks of a Great Pyrenees, and my cattle dog’s smaller versions. But handing off the poem to you, I know that I’m simply offering half of a circle, that if you recognize from your own experience, you can complete with the rest of the figure. So maybe the poem suggests an alternate hemisphere in your world.

That’s the last part of the practice I want to underscore. The central idea of sharing haiku with others is to offer a similar opportunity to practice. An invitation so clearly wrought in words that the invisible you perceived is offered to the reader just as invisibly. Whatever it is you have grasped, still remains just out of reach. Resides on the tip of the tongue. Walks on thin ice. Each person who reads your words can be surprised by the visible, and yet recognize it.

You will have invited each reader, one at a time, into their present.

Michael J. Rosen.

Michael J. Rosen is the creator of a wide variety of more than 100 books for both adults and children. A poet, fiction- and non-fiction writer, humorist, illustrator, editor, and, as of 2013 and the premier of “Elijah’s Angel: A Play for Chanukah and Christmas,” a playwright.

Rosen’s many children’s books, such as CHANUKAH LIGHTS, a poetic collaboration with pop-up master Robert Sabuda (Candlewick); BONESY AND ISABEL (Harcourt); and ELIJAH’S ANGEL (Harcourt), have received many distinguished citations, among them, the Sydney Taylor Book Award from the Association of Jewish Libraries, the National Jewish Book Award, the inaugural Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance Once Upon a World Book Award for the best children’s book that promotes diversity and tolerance, and the Ohioana Library Career Citation in children’s literature. Fifteen of his books such as DOG PEOPLE and HORSE PEOPLE (Artisan), HOME (HarperCollins) and THE GREATEST TABLE (Harcourt), were created with the generosity of hundreds of the country’s best-known illustrators, photographers, authors, and cartoonists as creative philanthropy. Their profits benefitted the Share Our Strength’s work to end childhood hunger and a granting program he created, The Company of Animals Fund, that awarded over $375,000 to 100 animal welfare organizations.

For over 40 years, ever since working as a counselor, youth-services director, day-camp director, and teacher at local community centers, Michael has been engaged with young children, their parents, and teachers. He has taught poetry and other forms of creative expression to adults and youth at literature conferences, colleges, libraries, and many nontraditional learning environments. As a visiting author, in-service speaker, and professional workshop leader, he has traveled to well over 700 schools and conferences around the nation.

Recent books include: a picture book, THE FOREVER FLOWERS (Creative Editions); a six-book series of nonfiction humor for third/fourth graders entitled NO WAY! that features a volume on world’s most eccentric sports, jobs, foods, buildings, medical practices, and forms of transportation (Millbrook/Lerner Books); a novel in poetry and two voices, RUNNING WITH TRAINS (Wordsong) set in 1969 that interweaves the lives of a divorced boy commuting between cities on the B&O Railroad and a younger farm boy whose land the railroad crosses; and SAILING THE UNKNOWN: Around the World with Captain Cook, a free-verse diary of a stowaway aboard the ship Endeavor (Creative Editions).

For older readers, he’s just published two books of non-fiction with Twenty-first Century Books: GIRLS VS. GUYS: The Surprising Differences between the Sexes, and PLACE HACKING: Venturing Off Limits.

His poetry for adults has been collected in three volumes: A DRINK AT THE MIRAGE (Princeton University Press), TRAVELING IN NOTIONS: The Stories of Gordon Penn (University of S. Carolina Press), and TELLING THINGS (Harcourt Brace). A fourth collection, GEORGICS, is in production at Cat Steppe Press.

He lives on a 50-acres in the foothills of Appalachia, east of Columbus.

Michael’s Website is www.fidosopher.com.

March 30, 2015

April is the cruelest (AND FUNNEST) month!

Hello, readers!

March is ending, and, for me, that means a month of absolutely delightful chaos is about to ensue. As a poet, I look forward to April every year. April is National Poetry Month, which means I’m celebrating in numerous ways! And, this year, it’s busier than ever!

Starting April 1, there will be a pretty incredible line-up of poets (and poetry lovers) guest-posting here on the blog while I go off to conquer other tasks. I hope you enjoy their posts. Because, man, there are some exciting people with exciting ideas that will be hanging out here over the course of the month.

Meanwhile, I’ll be over at PoMoSco.com, posting new poems every day based on prompts provided by Found Poetry Review. This year, they are celebrating national poetry month with a scouting-esque experience. Each challenge represents a badge that we can “win” for completing the challenge. There are 30 badges, and you know I want to collect them all! We got to start ahead, which is great, since I’ll be traveling this month. I’ve already enjoyed working with source texts like DEENIE by Judy Blume, a Buffy Season 8 graphic novel, and an X-Files transcript!

Meanwhile, I’ll be over at PoMoSco.com, posting new poems every day based on prompts provided by Found Poetry Review. This year, they are celebrating national poetry month with a scouting-esque experience. Each challenge represents a badge that we can “win” for completing the challenge. There are 30 badges, and you know I want to collect them all! We got to start ahead, which is great, since I’ll be traveling this month. I’ve already enjoyed working with source texts like DEENIE by Judy Blume, a Buffy Season 8 graphic novel, and an X-Files transcript!

So, the traveling? Yep, I’ll be at AWP in Minneapolis! (HOME OF PRINCE!!!) where I’ll be reading, signing, and taking in all of the awesome lectures and panels that I can. I’ll also be exploring the city with PoMoSco scouts, on a special FPR mission to earn some extra badges, which will culminate in a reading on Friday, April 10. So, you know, don’t miss that. (More details on my AWP schedule can be found on my Events page.) I’m so excited to meet so many of my new poetry friends and, finally, the team at Red Bird Chapbooks, who are based in St. Paul.

And I’m making some “Raspberry Beret” hair clips to go with bookmarks announcing my new chapbook forthcoming with Porkbelly Press. Gotta take advantage of the Minneapolis locale! Here’s the supplies I have so far. We’re ALMOST ready to get started:

Crafty time!

And then there’s TLA. I’ll be signing on Wednesday in the author area and also at a date/time TBA at the Overlooked Books booth. So keep an eye on that schedule if you want to come see me and get some books signed! I always love TLA — visiting with educators, librarians, readers and authors, chatting with publicists about awesome new books, and learning more about the industry.

Toward the end of the month, things should be winding down. But there will be daily guest posts here, daily poems at PoMoSco.com, and, you know, MAYBE a reading from Texas PoMoSco participants. I’ll let y’all know if this happens via Twitter & Facebook. Hoping we can pull this off, because, you know, how awesome would that be?

So, that’s my April. What are you doing to celebrate National Poetry Month?

March 28, 2015

7 Questions I Always Ask +1 with Alyxandra Harvey, author of RED, The Lovegrove Legacy and STOLEN AWAY)

Alyxandra Harvey is always a delight—a poet and novelist (with so many books out I can’t count them all in my head), her work is so full of spunky characters, dangerous intrigue, and good, old-fashioned fairytale fun. So when I got word that she was down for 7 Questions +1, I was super pumped. Here’s what she had to say:

E. Kristin Anderson: What was the first spark of inspiration for your latest novel?

Entangled Teen, March 2015.

Alyxandra Harvey: Usually a first line or a character starts poking me until I have to write their story. I also wanted to play with gothic stories and fairy tales because that’s always fun. And I’d already written about so many supernatural creatures: vampires, dragons, werewolves, ghosts, Fae, witches… I thought, why not put them all together? What happens when you have a zoo full of manticores and griffins and whatnot?

Plus, Kia’s voice was very loud and distinct and a little edgier than some of my previous characters so that was fun too.

EKA: What kind of planning do you do before you start writing?

AH: I jump right in with a first scene and a character and see where they will lead me. Unless I’m writing something historical and then I spend a few weeks re-immersing myself in the time period. I love the research, books, taking notes—and watching movies. Not for historical accuracy of course, but for atmosphere. Plus, I can claim watching Pride and Prejudice as ‘working’

EKA: If you could have lunch with any writer living or dead, who would it be?

AH: I’d love to have lunch with Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters—but maybe just tea and cake. Because 19th century food? Boiled calves feet, tongue, weird jellies, magotty stilton cheese… um, no thanks.

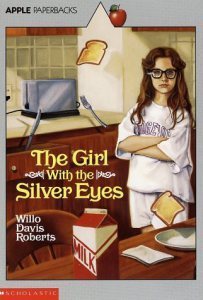

EKA: What is the first book you remember reading and enjoying as a young reader?

Scholastic, Reprint Edition, January 1991.

AH: I was apparently obsessed with THE PRINCESS AND THE PEA, THE JUNGLE BOOK and LITTLE HIAWATHA. I vaguely remember a book I think was called THE GIRL WITH THE SILVER EYES? And the Sweet Valley High series of course, which were $2.95 and I had $3 allowance and would read them on the stairs because I couldn’t even wait to get up to my room. And in grade 9—The Dragonlance books and The Belgariad by David Eddings. Oops. Ok, that’s more than one book . Occupational Hazard.

EKA: If you could go back and time and tell your teen self ONE THING AND ONE THING ONLY, what would it be?

AH: Calm That Shit Down. You’re 15—don’t worry so much, my little Capricorn. (And, on a related note, FFS you’re not fat and if you were—so what??)

EKA: If you haven’t had a book challenged or banned, would you want this to happen to you? Why or why not?

Bloomsbury USA Children’s, October 2014.

AH: I haven’t had a book banned. I’m sure it would be frustrating but also the kinds of things that get banned—same sex relationship etc? I’d happily be banned for writing more love into the world.

EKA: What kind of book do you really want to try to write, but haven’t ever attempted? And what do you think is holding you back?

AH: I just finished writing a post apocalyptic fantasy and that was the kind of thing I never thought I’d write. I wrote a short story called “Green Jack” (Urban Green Man anthology) and then found I just didn’t want to let it go so I went deeper.

I also love alternative future stories—the kind you get in an established series (usually tv). What if one thing changed—the vampires won or we were invaded by aliens or whatever—I’d love to try that one day. It’s very specific though, you have to already be in such an established well known story universe.

EKA: Your character, Kia, has a thing for fire. What are some of your favorite fire-y stories?

AH: I tend to get my fire fix from comics—Hellboy and X-Men etc. I’m not great with fire—I am just mastering the art of building a proper campfire so I often think it would be a great super power. But without the blisters and burns and forest fires that Kia has to deal with…

Alyxandra Harvey

Alyxandra Harvey lives in a stone Victorian house in Ontario, Canada with a few resident ghosts who are allowed to stay as long they keep company manners. She loves medieval dresses, used to be able to recite all of “The Lady of Shalott” by Tennyson, and has been accused, more than once, of being born in the wrong century. She believes this to be mostly true except for the fact that she really likes running water, women’s rights, and ice cream.

Aside from the ghosts, she also lives with three dogs and her husband. She likes chai lattes, tattoos, and books.

Find Alyxandra Online:

Website: http://alyxandraharvey.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/alyxandrah

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AlyxandraHarvey

March 21, 2015

What Is a Chapbook?

Recently I wrote this piece for Project Educate: Publishing Week over at deviantART.com. But I thought it would be relevant and interesting to my readers here, too, so here it is! I’m sharing it! Enjoy!

I’m so glad you’re here. Because, as a poet and chapbook author, I get this question a lot. AND, since chapbooks are an important part of poetry publishing — both in terms of what we consume as readers and what propels us forward as career poets — any poet with publishing aspirations should know about them!

The Short Version:

A chapbook, sometimes referred to as a pamphlet, is like a mini collection of poetry. Usually between fifteen to thirty pages (though some folks say anything under 50 pages is a chapbook), these are like little samplers of a poet’s work. Usually the chapbooks are pretty cheap, between $6 and $12, which also makes them super fun and easy to collect for readers.

A Bit of History:

Chapbooks were popularized in Europe in the 16th century, and were mostly produced for consumption by folks who might not otherwise be able to buy books. They were made on the cheap and weren’t always pretty, but that worked out, since, back in the day, they were often discarded and repurposed after reading. We didn’t see them for a while after the 19th century, but within the last hundred years, they’ve popped up again, primarily in poetry circles, but also as a venue for short prose.

How Chapbooks Come Together:

Often chapbooks work within a theme. Because they are short, there has to be a feeling that the poems are somehow interconnected, even more so than in a full-length collection. Threads that connect poems in a chapbook could be anything from a specific topic (like current events, mythology, or pop culture) to a poetic method (using a fixed form for each poem, found poetry from a specific source text, or some other challenge) to personal poems that tell a story.

Why Do They Look Kinda Funky Sometimes?

Sticking to historical tradition, there’s a DIY ethic (much like with modern zines) that’s popular in the chapbook world. Many chapbooks you find in stores or at readings are still hand-made, often silkscreened or hand-bound with needle and thread. Sometimes you can see where the publisher has cut the paper just slightly off, and stapled the books together with love. Sometimes unique bookbinding and printing techniques are used that you couldn’t use for mass-produced books. Of course, there are chapbooks that are perfect bound (where the spine is flat, rather than stapled or stitched, which is called saddle stitch) on “regular” paper, using contemporary methods. One style isn’t necessarily better than the other, but they’re both totally legit. It’s also worth noting that the DIY nature of chapbooks makes them an easy and accessible way for poets to self-publish work, which they can then distribute and sell at readings.

PS, E-Chaps Exist!

Of course, we live in the digital age, and it’s not hard to find e-book versions of chapbooks, often referred to as e-chaps. Some publishers even go so far as to only print e-chaps, and others make e-chaps available after limited edition print runs have sold out. It is not ucommon for e-chaps to be distributed for free. This, of course, has lead to some debate in the poetry community, as while some believe that art for art’s sake does mean giving work away, others believe that art for art’s sake and compensation for the value of art are not mutually exclusive. Either way, if you want a quick and easy way to get a chapbook onto your e-reader, look for publishers who publish electronically, either exclusively or alongside their paper books. (I recommend Sundress Publications, Bloof Books, and ELJ Publications as places to start reading!)

What’s Up With Chapbook Publishers and Contests?

One tough thing about chapbook publication is that many presses that publish chapbooks only accept submissions through contests, and most of these contests have reading fees between $10 and $25. There are chapbook publishers that have regular open reading periods (some have reading fees, some don’t) and there are contests with very minimal or no reading fee…but the hard truth is that if you want to publish a chapbook, you will probably have to make a bit of an investment. Chapbook presses are so small, that many use these reading fees to sustain their presses and pay their authors. All of this, of course, goes against everything you’ve ever learned about traditional publishing and money (money always flows TO the author, right?) — but it’s one of the weird and rare exceptions. Personally, I like when a reading fee includes (or gives the option to include) a chapbook from the press. So those might be contests you specifically want to look at.

I’ve Polished My Manuscript. How Do I Get Started With Submitting My Chap?

When you think you’re ready to publish a chapbook, I think that the reading fees involved make it even more important to do your research and submit selectively. Most chapbook publishers have a clear aesthetic, which you can find both by reading the guidelines and samples on their website and by buying a book or two from them (because of their size, niche, and production style, chapbooks are hard to find in libraries).

I Want to Read Some Chapbooks. Any Recommendations?

So, you’re wondering where to start? Throughout this post are pictures of some of my fave chapbooks that I’ve read recently. Click them! I think these books are excellent, accessible, and mostly cheap. They are also put out by presses that I love and respect. I hope you’ll take a peek and support these small presses and poets!

Any final questions on chapbooks? Put them below, and I’ll do my best to answer them!

March 20, 2015

Review: TICKER by Lisa Mantchev

There are just so many things to love in TICKER by Lisa Mantchev that I don’t know where to start. It’s steampunky goodness, with mystery and scandal and fun tech and all the subversion that a girl could want in a spunky heroine. I had so much fun reading TICKER. Here’s why:

1. There aforementioned spunky heroine isn’t afraid to take down the boys. Literally. I think her first encounter with the “hero” is slamming straight into him and attacking him with her “pixii” which, so far as I can tell, is something like a miniature steampunk lightsaber.

Skyscape, December 2014.

2. I say “hero” because there are multiple heroes. There’s the leading lady, Penny Farthing, who does her share of kicking ass, Buffy/Scully/Starbuck style. And there’s her brother, who is basically steampunk Q, making some super gadgets and doing his best to keep Penny from overworking her clockwork heart (heart attacks are bad, y’all). And then there’s Penny’s BFF who runs a bakery and has adorable tattoos. And then there’s Penny’s brother’s BFF who can ply anyone in town with either money or charm — and he doesn’t discriminate when it comes to charming either gender.

3. Did I mention the heart attacks? Penny has a clockwork heart. Which means she really probably shouldn’t be riding around on her motorbike and chasing down badguys. But when it turns out that her parents seem to have been kidnapped by the man who MADE her clockwork heart, she’s not going to take that lying down. Plus, as the kids say these days, you only live once, and Penny doesn’t want to waste what time she has left.

4. And then there’s the dude who’s leading the police force. He makes Penny’s heart go pitter pat. Or tickety tock. But she can’t tell what side he’s on. Hence the pixii attack. Among other things.

5. In case you couldn’t tell from items 1-4, these characters are 100% real. They make mistakes, they have ambitions. They have loves and losses and talents and disasterous flaws.

There isn’t a slow moment in this book. Not one. Which makes this book one you absolutely must not miss. MUST NOT. I really hope there are futher books in this universe. Lisa Mantchev is a genius. Fantasy and sci fi readers alike will enjoy this. And I’d like to think that contemporary readers will dig it as well. Someone give TICKER some awards already!