National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Michael J. Rosen: Writing On Ice

Writing on Ice

With the recent publication of THE MAINE COON’S HAIKU AND OTHER POEMS FOR CAT LOVERS, the third volume in a series of books that culls poems from my ongoing practice of writing haiku, I pulled together these fragments, these reflections, for National Poetry Month. Also included: half a dozen haiku that were written this winter that are not a part of the book. Many thanks, EKA, for the invitation to share this!

Turning Visible

Candlewick Press, March 2015.

How quickly, without our even realizing it, something remarkable becomes routine. Novelty turns invisible. Something that once grabbed the attention (and that’s the right verb! Something grabs, seizes, plucks our awareness from a lulled or impatient inventory of the present), eventually, all too quickly, loses its grip. Once we can recognize or expect that formerly-arresting something, our senses check it off the life list and listlessly go about their business until the next something interrupts that maundering. They idle until we consciously shift them into gear again.

In terms of survival, there’s a positive rationale for this. It behooves every species to quickly evaluate dangers and threats, and then to cease focusing on those that are neither likely nor imminent. Likewise, our human brains can’t consciously enumerate or name or respond to every stimulation the senses present every waking instant; we learn to attend to the essentials as well as tune out the inessentials. For better and worse, our minds become inured and dismissive; our emotions turn callous; our senses wear blinders, or their sensitivity wears out.

So it requires a deliberateness, a retraining of sorts, in order to open our consciousness to the familiar. To be patient enough with the commonplace to find the exceptional nuances that often afford even more pleasure than something wholly or newly remarkable. I say “even more” because, while the unfamiliar affords the pleasure of surprise, the familiar— one refreshed, once encountered with genuine openness—affords both the pleasure of recognition and that of surprise.

A practice of haiku can be the practice of turning the familiar visible again. Of removing the “over” from “overlooked.” Of refusing to let “over and over” govern your watch.

The Importance of Being There

Last summer, I went to a mind-blowing house concert by a remarkable singer/songwriter. A total of 50 people gathered in a two-story horse barn that had been converted into an inviting performance space and microbrewery. For 90 minutes, the loft reverberated with just one voice and one guitar. On overstuffed coaches, on floor pillows and picnic blankets, no one sat farther than 15 feet away from this powerful singer’s earnest, plaintive, urgent, contagious spirit. The room resounded, shuddered, thrummed, and ached with his soulful, ambitious, acoustic presence.

And a full third of the concert-goers viewed the entire performance on their cell phones. They focused on holding their devices still. They stared at the tiny 2-D face on the screen, rather than the full-size 3-D performer almost within reach. They concentrated on keeping the musician’s body in the center of their screen, on shifting this way or that way when someone in front of them shifted and blocked their camera’s line of sight.

Candlewick Press, September 2011.

For those recording the singer, it seemed more important to have been there, than to actually be there. More significant to have something to share/post of their having been there…than to be immersed, abandoned, open—vulnerable, even—to the power of the performer and his music. They missed the subtle expressions of the singer connected his eyes with listeners’ eyes, modulated his falsetto or ramped up his bellowing notes, or basked in the reverberations of his notes among the 200-year-old rafters. They missed the way the dimming sun flickered patterns against the wall-size fireplace behind the performer.

Maybe they’ll remember more of the concert than I will recall. Certainly they’ll have something with which to remind themselves, assuming the quality of a phone’s recording is really something worth replaying…once, let alone, more than once. They’ll have proof.

But they won’t have vivid memories of actually absorbing, feeling that precise experience. Their eagerness to keep the experience meant they never lost themselves in it.

In 1930, Robert Frost wrote, “Strongly spent is synonymous with kept.” I live by that 85-year-old idea. I believe that “strongly spending” time at a concert—simply (It’s clear that “simply” isn’t all that easy, right?) listening to the man playing and singing—would have been more memorable than the keeping of a recording.

This practice of living in the future tense—what I will do with what is happening now—is antithetical to satisfaction in life. I think our greediness with documenting, with posing and posting, with much of technology’s easy record of here and now, whittles away at the profound pleasure of taking part in what is taking place. And of witnessing. Truly being present—witnessing—is what shapes our character, hones our empathy, and builds our appreciation of and respect for difference.

Seeing Still

I teach a workshop called “Seeing Still.” It’s very much like what most yoga teachers will say at the start of class: Focus on what is happening precisely on your own mat, at this given time. Relinquish thoughts of past performance and future expectation. Ignore the pressing duties and niggling details that stand just outside the studio. So my writing workshop is a session on “sitting still”…but with the mind. It’s a workshop on “standing still,” but with the senses held in place rather than the feet.

Granted, it is difficult not to fidget. It takes practice. But one thing practice makes—one thing that often is eclipsed—is its capacity to afford us pleasure. The pleasure of repetition. Of simply trying hard. Of being willing to try again.

So practice may make perfect, but it always makes us happy.

Writing on Ice

We can walk and never think about our feet. Once we’ve mastered a gait—our first steps as a toddler, the choreography of a few dance moves—our autonomic nervous system ensures that the muscles and nerves are innervated accordingly. Feet are placed correctly, adjusting and advancing without directions from the conscious pilot.

Photo by Michael J. Rosen

But we can commandeer most of those actions. Voluntarily, we can step more quickly, plant our feet farther apart, touch down with the toe first rather than the heel.

This last winter, hiking with my dog on our snow-covered paths or even leash-walking in the city, my steps outdoors required far too many voluntary actions. While I didn’t need to call out tendons by name, warn one ankle’s tendons to roll with the swiveled joint, order each hip joint to soften or stiffen to keep me from falling, most every step announced itself with a wince or pain, pressure or resistance—or a lack of resistance. My gait was unpredictable, as I gauged the position and pressure to put into each step, as I decided whether to lift above or shuffle through the accumulated snow and ice, as I guessed whether to step lightly, slide, stomp, or stop.

winter, what options

you leave! foot-deep snow or path

of packed-ice boot steps

Photo by Michael J. Rosen.

Likewise, we can converse without really thinking. And we can write that way. My idea of “seeing still” is to persist in the action of seeing, rather than in the inaction of a snap perception. Sustain the observations of a prolonged encounter, rather than opt for a sense of completion and its associated relief.

Let me stick with this winter’s hikes. Writing haiku is much more like walking on ice. It offers some autonomy to the brain that might believe it knows what you’re doing, but it also withholds some control in order to guide the words marching forward with more deliberateness, more choice, more distinction. Writing haiku is placing words in the natural, unnatural manner of taking steps intentionally, voluntarily.

It’s like walking on ice. Thin ice.

Tumbling

Very often, my practice of writing haiku is more like tumbling a few crude gemstones than cutting and polishing one into a single sparkling cabochon. I’m less driven to the destination of a single haiku that’s perfect because such finessing can risk becoming precious. Or maybe sentimental: wrapping up the experience or moment too handily; harrowing too much tone and variation in order to hone that pithiest form. So most of the haiku I keep are saved in variations on a page. Each treads water…somewhere between sinking and swimming.

Again, I look for the pleasure in recognizing something unexpected, in stumbling upon something unpredicted.

Ah

Photo by Michael J. Rosen.

It’s been said that haiku lives on the tip of the tongue. It’s…it’s…not that, but I’ve almost got it—wait! It’s right on the tip of my tongue…. But then it’s never quite uttered. There a tradition to just let a haiku be—simply be. Not be a description. Not be a definition. Not be something that evokes a question or a comment from the reader. Not be an “aha!”…only an “ah….” An expression that might be translated as, “Now, I see it.”

cat’s frozen paw prints

heading the opposite way

in last night’s boot prints

•

this morning’s cat tracks

frozen in last night’s boot tracks

coming and going

•

heading out, I find

cat tracks—frozen in last night’s

book tracks—heading in

Mannix.

A Winter with Cats

As promised, in light of the publication of THE MAINE COON’S HAIKU AND OTHER POEMS FOR CAT LOVERS, here is a sampler of haiku written this winter.

They feature or suggest the cats—Slinky, a mackerel tabby, and Mannix, an orange-and-white Manx—who share my acres.

out in out in out

invisible doors are all

the cats know about

•

eggshell of clear ice

tiptoeing paws skirt the pond—

not breaking silence

•

in fresh sparkling snow

even the cat’s faint pad-prints

cast heavy shadows

•

winter stretches land

across the pond—and cat claims

a sudden acre

•

old snow, it takes you

to remind me how many

travel this same way

Of this last haiku, hewed directly from my very local observations, it didn’t occur to me to think about someone in a city, someone in an utterly different locale, reading it. I grounded the poem in the acres here: I saw the split-hearts of the deer’s hooves, the warm stamp-pads of the cat’s toes, the various point sizes of the bird’s Ys, the “great” tracks of a Great Pyrenees, and my cattle dog’s smaller versions. But handing off the poem to you, I know that I’m simply offering half of a circle, that if you recognize from your own experience, you can complete with the rest of the figure. So maybe the poem suggests an alternate hemisphere in your world.

That’s the last part of the practice I want to underscore. The central idea of sharing haiku with others is to offer a similar opportunity to practice. An invitation so clearly wrought in words that the invisible you perceived is offered to the reader just as invisibly. Whatever it is you have grasped, still remains just out of reach. Resides on the tip of the tongue. Walks on thin ice. Each person who reads your words can be surprised by the visible, and yet recognize it.

You will have invited each reader, one at a time, into their present.

Michael J. Rosen.

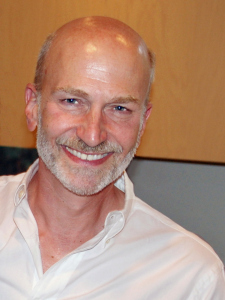

Michael J. Rosen is the creator of a wide variety of more than 100 books for both adults and children. A poet, fiction- and non-fiction writer, humorist, illustrator, editor, and, as of 2013 and the premier of “Elijah’s Angel: A Play for Chanukah and Christmas,” a playwright.

Rosen’s many children’s books, such as CHANUKAH LIGHTS, a poetic collaboration with pop-up master Robert Sabuda (Candlewick); BONESY AND ISABEL (Harcourt); and ELIJAH’S ANGEL (Harcourt), have received many distinguished citations, among them, the Sydney Taylor Book Award from the Association of Jewish Libraries, the National Jewish Book Award, the inaugural Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance Once Upon a World Book Award for the best children’s book that promotes diversity and tolerance, and the Ohioana Library Career Citation in children’s literature. Fifteen of his books such as DOG PEOPLE and HORSE PEOPLE (Artisan), HOME (HarperCollins) and THE GREATEST TABLE (Harcourt), were created with the generosity of hundreds of the country’s best-known illustrators, photographers, authors, and cartoonists as creative philanthropy. Their profits benefitted the Share Our Strength’s work to end childhood hunger and a granting program he created, The Company of Animals Fund, that awarded over $375,000 to 100 animal welfare organizations.

For over 40 years, ever since working as a counselor, youth-services director, day-camp director, and teacher at local community centers, Michael has been engaged with young children, their parents, and teachers. He has taught poetry and other forms of creative expression to adults and youth at literature conferences, colleges, libraries, and many nontraditional learning environments. As a visiting author, in-service speaker, and professional workshop leader, he has traveled to well over 700 schools and conferences around the nation.

Recent books include: a picture book, THE FOREVER FLOWERS (Creative Editions); a six-book series of nonfiction humor for third/fourth graders entitled NO WAY! that features a volume on world’s most eccentric sports, jobs, foods, buildings, medical practices, and forms of transportation (Millbrook/Lerner Books); a novel in poetry and two voices, RUNNING WITH TRAINS (Wordsong) set in 1969 that interweaves the lives of a divorced boy commuting between cities on the B&O Railroad and a younger farm boy whose land the railroad crosses; and SAILING THE UNKNOWN: Around the World with Captain Cook, a free-verse diary of a stowaway aboard the ship Endeavor (Creative Editions).

For older readers, he’s just published two books of non-fiction with Twenty-first Century Books: GIRLS VS. GUYS: The Surprising Differences between the Sexes, and PLACE HACKING: Venturing Off Limits.

His poetry for adults has been collected in three volumes: A DRINK AT THE MIRAGE (Princeton University Press), TRAVELING IN NOTIONS: The Stories of Gordon Penn (University of S. Carolina Press), and TELLING THINGS (Harcourt Brace). A fourth collection, GEORGICS, is in production at Cat Steppe Press.

He lives on a 50-acres in the foothills of Appalachia, east of Columbus.

Michael’s Website is www.fidosopher.com.