E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 12

March 7, 2015

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Megan Jean Sovern: The Smart Girl Story

Chronicle Books, May 2014.

When I set out to write THE MEANING OF MAGGIE about a smart girl I tried to stay true to one important thing: brutal honesty.

Because while smart girls are tenacious and kind and intuitive. We are also emotional and complex and care more about our eyebrows than we probably should. You can’t have a character who is all of the good things about being a smart girl and none of the bad.

At her very best Maggie is determined, full of heart and hilarious. And at her very worst she is selfish, naïve but also hilarious. She can be open and give her all to someone else. And she can be closed off and care only about her own feelings. But even when you’re disappointed in her, I still want you to root for her.

Young Megan with her family.

Because I know that when I was a kid, I became every character that I read and connected with. I was Ramona Quimby and my older annoyed sister was Beezus. I was the round-faced Linda Fischer from BLUBBER. And I was neither of the SWEET VALLEY HIGH twins but I really really wanted to be.

So my hope of all hopes is that young smart girls see in Maggie everything I see in them. They should be proud of who they are and who they are destined to become. No matter how squirrely their eyebrows are.

Megan Jean Sovern.

Megan Jean Sovern is a purveyor of fine teas, old time-y music and hugs. Recently she was in a bad break-up with muffins and her life hasn’t been the same since.

She’s often mistaken for a seventh grader but don’t be fooled, she is very grown-up. A grown-up who watches television past ten o’clock and everything.

Before her first leap into fiction, she was an advertising copywriter for many moons where she worked with top-notch talent mostly named Matt or Karen.

She lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her husband Ted, their daughter Evelyn and Ted’s his near complete collection of Transformers.

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Kathryn E. Livingston: Writing My Way Through the Winds of Change

When I sat down to write my memoir, YIN, YANG, YOGINI, I was a different woman than she who rose up from her desk several years later (it goes without saying that a few coffee breaks happened along the way). During the process of writing, my life took some unexpected turns, and as a result, so did my memoir. When I began to write, my mission was to chronicle the ways that yoga (which I had just begun practicing) was changing my life. But a breast cancer diagnosis during my second year of the project slightly altered my course, and writing became an anchor that would keep me centered during a challenging time of transition.

Open Road Media, April 2014.

There was no way I could have known when I began to write the memoir, that it would have anything to do with cancer at all (frankly, I’ve always shied away from books that tackle the subject, as if reading about it would somehow hex me; lotta good that did!). I certainly would not have wished for a breast cancer diagnoses to fuel my writing; yet there it was. On the one hand, a frightening, life-threatening disease. On the other, an opportunity to face change head-on and emerge victorious.

In my early fifties, I had started practicing yoga at the suggestion of a therapist to deal with my burgeoning anxiety about my kids (three sons) growing up and leaving home for college, my mother’s then-recent death, and my fear of what I would do with a life that had become distressingly unfamiliar. Of course, I knew I would keep writing no matter what because I’d been a writer since the age of five. But I also knew that even my writing would have to change—I no longer had an interest in pitching stories about temper tantrums or homework hassles to parenting magazines. I had a deep-rooted desire to write something that might actually change lives.

Enter yoga, and my realization that nothing –other than motherhood and sex—had touched my body and soul like this. When I began—nearly a decade ago—yoga was not yet on every corner and yoga pants were not a fashion necessity. Though yoga had been spreading for a number of years, its popularity had totally eluded me, so I was surprised and energized by the shift I sensed at my very first class. After each session I would come home and journal, noting the ways the practice was improving my physical and mental flexibility, my sense of balance and trust, my outlook (which had always been glass-half-empty), and many other things (including my waistline). Within a year of study, I had changed dramatically, and just in time! The woman I had been pre-yoga would surely have collapsed in a heap at the mere mention of cancer.

They say that motherhood changes everything, and I found that to be true. But cancer is an equally if not more formidable game-changer. Life pre-cancer and post-cancer are two different ballgames. And like so many women (Elizabeth Gilbert and Cheryl Strayed come to mind) who have used writing to steady them or to share the lessons learned through a storm, I dove into my memoir with even more devotion. Now it wasn’t just a memoir about how yoga could change a life; it became, at least in part, a memoir about how yoga could help one find the strength and courage to face one’s own mortality.

Perhaps that sounds a bit serious, and a serious memoir YIN, YANG, YOGINI: A Woman’s Quest for Balance, Strength and Inner Peace really is not (I’ve tried to infuse it with a healthy dose of hilarity). The message, however, isn’t a joke: that whatever your issue is—fear, anxiety, grief, self-doubt, depression, body image, cancer, addiction, something else, or all of the above—yoga can help. (One caveat; you do need to discover the teacher and style that works for you, which I was blessed to stumble upon at the get-go: thank you, Universe!).

Doing the yoga was one thing. Getting to my desk every day to write about how yoga was helping me was another, and the combination somehow got me through the cancer journey (along with more than a little help from my family and friends, of course). I also decided if I got the book published, I’d give a portion of my earnings to breast cancer research (not surprisingly, my agent found a publisher the day after I made this vow).

These days, I’m still a writer, but I’m also a Kundalini yoga teacher. I’ve replaced writing about colic and ear infections with pieces about mantra and meditation. I’ve learned to embrace that thing called “change” that used to cause so much anguish. I’ve learned to let my writing flow where the winds of life take me. Post cancer, nothing is taken for granted anymore. Not even the pen in my hand.

Kathryn E. Livingston.

Kathryn E. Livingston is a Kundalini yoga teacher and the author of YIN, YANG, YOGINI: A Woman’s Quest for Balance, Strength and Inner Peace (Open Road Integrated Media, 2014). She lives in New Jersey with her husband and one son who has temporarily flown back to the nest. She also blogs for The Huffington Post and the yoga music website Spirit Voyage. Visit Kathryn at livwrite.blogspot.com, follow her on Twitter or find her on Facebook.

March 6, 2015

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Kristen Simmons: No Matter What You Look Like

People who know me typically give me the same look when they read my books – the But-You-Seemed-So-Well-Adjusted look. It isn’t that I’m not (really, I swear), but that my books, to some, are dark. They’re about worlds where danger lurks at every turn, where wars have destroyed cities, and trust is a luxury few can afford. But to me, all this is meant to highlight one thing: hope.

Tor Teen, February 2015.

A dystopian story is just a magnification of the world we live in – a more extreme focus on the challenges we face every day. All of the frightening, negative things that we are confronted with here – injustice, and persecution, and mistrust – come to life in a bigger, bolder way. And though the world may be presented in a harsher light, a dystopian story’s purpose is to measure humanity’s resilience. The setting forces characters to be stronger, wiser, and braver. To make choices that impact their survival – choices that, in the end, have potential to show great growth. To give us hope that our struggles here, in this world, are not in vain.

My next book, THE GLASS ARROW, carries on the path forged by THE HANDMAID’S TALE. It’s a story about female oppression, where the census is controlled and women are reduced to their ability to conceive. Like in Offred’s story, there is a focus on the conceptualization of one’s identity as a woman in a highly discriminatory world. Questions arise like, How do I make myself matter? Am I pretty enough? Will they like me? Is it important that I’m smart? Real-world issues are faced, such as human trafficking, threats to safety and freedom, and the use of physical appearance as a measure of one’s worth. Girls are assigned number ratings on their beauty by an outside source. They’re taught that latching themselves onto a wealthy, powerful, or good-looking partner is the only way to get what they need. They’re taught that they are simply not as good as men.

It’s into this world that I throw the fiercest girl I have ever imagined, and I’m proud to say, she does not let the bastards grind her down.

Being a girl isn’t easy. (It isn’t easy being a boy either, what with all the pressure on “being a man,” though I can’t speak as personally on that.) It takes strength and courage, even under the best circumstances. The concepts in THE GLASS ARROW aren’t fictional, but they can be changed with time and dedication. The more we empower girls, the less we see young women judging their worth by the size of their pants, and more by their achievements – their confidence, intelligence, and kindness. They, in turn, can perpetuate a culture of safety, where everyone is capable of greatness and worthy of love, no matter who they are, what they are, or what they look like.

Kristen Simmons. (Photo by Sasha Ledney Photography.)

Kristen Simmons is the author of the ARTICLE 5 series (ARTICLE 5, BREAKING POINT, and THREE), as well as THE GLASS ARROW (2015). She has a master’s degree in social work and loves red velvet cupcakes. She lives with her family in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Learn more about about Kristen and her books at www.KristenSimmonsBooks.com, and follow her on Facebook at www.facebook.com/author.kristensimmons and Twitter at @kris10writes.

International Women’s Week: Guest Post From C. Desir: A Few Christa Truths

If I’m being completely honest, I’d admit that the first draft of this essay was a litany of how sexism is very much alive and well when it comes to the world of writing and publishing. But as with most of my first drafts, I’ve decided to chuck that and start over. Here’s why: being a woman in this world is hard. This is not exclusive to publishing or writing. This is life. If you are a woman reading this, you know what I am talking about. #YesAllWomen did not come out of the ether. It came out of lived and shared experiences. So preaching to the choir seemed both redundant and reductive when it came to this essay. Instead, I thought perhaps it was time I put energy into celebrating women and offering a few random Christa truths.

Simon Pulse, October 2014.

Truth #1: Writing is a difficult profession. It is frustrating and defeating and occasionally wonderful and frequently awful and it is difficult. When I am hit in the face with good writing by men, I feel simultaneously jealous as hell and compelled to write better. When I am hit in the face with good writing by women, I mostly think, “Yes, good job, woman. You made it through the ice storm.” This perhaps is a little sisters before misters of me, but you’ll have to forgive me the indulgence. Yes, everyone has an ice storm. But for women, that ice storm comes with the burden of being a woman in a world that prefers to listen to men. For women of color, or women with disabilities, or women on the QUILTBAG spectrum, the ice storm also comes with a side of metaphorical fire ants. If you make it through, I am overjoyed. You’re doing awesome and I’m proud as hell of you. Thank you for pressing forward and fighting so hard so maybe our future children won’t have to.

Truth #2: Whatever you’re doing is enough, thank you very much. You don’t owe anyone pieces of your soul. You don’t have to give your power away because you think you don’t deserve to have it. You don’t owe anyone an apology for who you are or what you do. I apologize all the time. It’s a terrible habit, one that has been indoctrinated into me from the time I was very small. I apologize for bothering people, for daring to exist and ask for something I deserve, for pulling a little of the spotlight my way when I worked hard at something. I have a friend who once said to me, “I’d rather be a bitch than a doormat.” Frankly, I’d rather those weren’t the only two options.

Simon Pulse, October 2013.

Truth #3: There will come a time in your life when you will realize that you are being/have been carried on the backs of other women. It is a good thing to honor this and pay it forward in whatever way you can. It is a good thing to build women up instead of tear them down. I need to remind myself of this sometimes. We all do. There is grace and forgiveness, but above all, we must remember the ice storm. You don’t have to like every woman you meet, but it is worth considering the system they grew up in/with.

Truth #4: If you would like to be a woman writer, then read and support women writers in whatever way you can. Whether it’s in asking for their books at your library, buying their books as gifts, or telling your friends about them. It matters. These are the baby steps that propel us into a more level playing field. The first thing I did when my daughter started middle school was check out the school library and the curriculum for the year. I was delighted to see all the diversity on their shelves, but realized that wasn’t necessarily playing out in the curriculum since they were reading the “classics.” So I suggested companion novels to read along with the classics. I knew books to suggest because I had read them. Do this. Familiarize yourself with marginalized voices so that when the opportunity comes up, you can suggest a change.

To that end, these are books I have read recently by women writers I’d like to celebrate:

St. Martin’s Griffin, July 2015.

AN UNTAMED STATE by Roxane Gay

NONE OF THE ABOVE by I.W. Gregorio

LIVED THROUGH THIS by Anne K. Ream

CUT BOTH WAYS by Carrie Mesrobian

THE DEVIL YOU KNOW by Trish Doller

C. Desir. (Photo by Chris Guillen Photography.)

C. Desir writes dark contemporary fiction for young adults. She lives with her husband, three small children, and overly enthusiastic dog outside of Chicago. She has volunteered as a rape victim activist for more than ten years, including providing direct service as an advocate in hospital ERs. She also works as an editor at Samhain Publishing. Visit her at ChristaDesir.com.

March 5, 2015

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Désirée Zamorano: The Lives of Strangers

Before I sat down to draft my novel I knew I wanted to explore the lives of women. I find our simultaneous balancing acts entertaining and overwhelming. We commit to a social life, a partner, a career, perhaps children. We negotiate the demands of the people around us, attempt to manage the emotional lives of the family near us, while at the same time struggle to realize our own dreams. So many demands and needs to navigate and juggle. Add to that hopes and fears and disappointments.

Cinco Puntos Press, July 2014.

When I chat with audiences about my novel, THE AMADO WOMEN, I talk about its genesis. A novel is a multiple year commitment, and I wanted to be able to enjoy my time with these characters. They had to be complex and flawed, intelligent yet with blinders, ambitious as well as prone to inertia. In other words, very much like the women I know and love in my own life. I also wanted to explore the small moments of beauty buried in the rubble of the quotidian and the routine. And throughout, I wanted, as best as I could, to treat each of these women tenderly.

Am I saying men’s lives are less complicated or messy? Actually, I’m not saying anything at all about men’s lives, apart from how they impact the lives of my main characters. There are plenty of novels which do. Mine isn’t one of them. And that’s where people get kinda stroppy.

“Sounds like a woman’s book,” a male acquaintance of mine said, “I don’t think guys would be into it.”

I considered that statement. Don’t men have mothers, daughters, sisters? Don’t they wonder about their interior lives?

Another man asked, “Do you always write about Latinas?” Had I been a (white) man writing about (white) men, would he have asked me a similar question?

My glib answer: “If I don’t, who will.” Of course there are other authors who do. But my point was I don’t have to tell the stories of white men and women, they are well over-represented in the mainstream media. (A little math: Latinos are 20% of the US population. They are 50% of LA County, where I am from. And less than 5% of all speaking roles in the movies and television.)

Let’s be clear, none of us fit neatly into categories. There are a lot of identities or roles we embody, and no single label encompasses the entirety and complexity of who we are. Me? A few of my identities are: a woman, a Mexican-American, a writer. Some roles have been thrust upon us at birth, some identities we have fostered and cultivated, like spouse, parent, educator. But our human nature allows, often insists, that everyone else can be sorted into categories, neat and tidy because life is messy and stereotypes, oops, I mean categories, allow us take short cuts and get to the heart of the matter of one another more quickly. Don’t they?

These shortcuts/stereotypes/microagressions take on an awful life when used against artists. Reviewers betray our culture’s blinders: a woman’s novel written by an Asian American was reviewed as being “No Amy Tan.” Written by a Latina? It’s a telenovela. Written by a woman? Chick-lit. Written by a man? Literary fiction, of course.

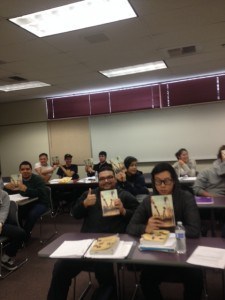

Désirée’s students with copies of her novel!

Recently I was honored by an invitation to speak at a local community college to two composition classes who had to read the novel over the course of the semester. Although I had spoken publicly about my writing numerous times, I was nervous. These students, predominately men, had been required to read the book. The instructor shared with me that she chose the book precisely because women readily read male-centric stories. She wanted to expose her male students to a woman-centric novel.

Over the course of two hours the give and take with students who have read the novel was overwhelmingly gratifying. And then a (male) student said, “To be honest, I despise reading assigned books. But I began to care for the characters. It made me really analyze the interactions we have as men and women. I feel this book is meant for men who’ve never walked in women’s shoes.”

So beautiful I had no words. I hadn’t ever thought of it in those terms. Now as I ponder his comment I realize that confirms the essence of reading fiction: to live and experience the interior story of strangers.

The next time I hear a note of male disdain regarding my “women’s book” I will whip out that young man’s insight and flay him with it.

THE AMADO WOMEN has been listed among 5 Must-Read Books for Summer 2014 by Remezcla, and has been named among Eleven Moving Beach Reads That’ll Have You Weeping in Your Piña Colada by Bustle. It was a Book of the Month pick for the Las Comadres National Latino Book Club. Désirée Zamorano has wrestled with culture, identity, and the invisibility of Latinas from early on, and addressed that in her commentaries which have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The Toast, NPR’s Latino USA and Publishers Weekly. She is delighted to be a speaker in the upcoming LABindercon.

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Susan Morse: On e-Books and a Label-free Future

My father gave me a boxed set of A. A. Milne on my sixth birthday, and I’ve read myself to sleep ever since. I’m not a good sleeper. It’s actually impossible for me go under without reading—I’ve tried. I once forgot my book on a trip and tossed for hours, finally lulling myself into semi-consciousness with a room service menu from the nightstand.

Open Road Media, September 2014.

There has been one exception: I went cold turkey for a week nursing newborn twins. I could barely remember my own name, let alone process words on a page. Sleep was scarce, vital, and to be achieved with military efficiency. Even so, I’d grab a squishy old Stephen King paperback, cut the lights, and lunge for the mattress. I couldn’t read THE STAND, but I could hold it, cradled gingerly to my tender breasts like a poultice; a promise that the deprivation would eventually pass.

My husband presented me with a Kindle the year they came out. I was dubious, positive I’d be one of those people who couldn’t give up the sensory aspect of reading—that reassuring bedside stack; the smell and feel of new pages; book jackets with their intriguing cover images, clues to major themes, and, most importantly, on either the back or the inside flap: the author photo, leaving no doubt of the writer’s gender and age. The face behind the words.

To my surprise, I became an instant e-convert. Sleep comes more easily with the Kindle. I barely have to move while I read—no more fuss turning pages, no fumbling for the light on the nightstand.

The loss is the book cover. I loved every minute of THE GOLDFINCH, but felt instantly cheated when I got to reading group and saw that little yellow bird on a friend’s hardback for the first time. When you download a book on my device, the first page you see is just that: the first page of text. I have to fight the thing, working backwards or sideways if I want to see the author’s bio, or even their name, and to be honest, I’m usually in too much of a hurry to get my eight hours of sleep.

I finished a highly recommended book recently—ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE—and loved it, devoured it, did not want it to end, but somehow I failed to register one basic fact until it was over: It was written by a man, not a woman. (I know I should have guessed. The book is set during World War II, but one of the main protagonists, the first character introduced, is female. I just assumed.)

Any fellow insomniacs need not fear confusion if they download my books and fail, like me, to do their homework before starting. It’s hard to miss the gender of a memoir writer. But I kind of think this disconnect I’m experiencing may turn out to be a good thing for women writers who are sick of being labeled Women Writers. What sort of world would it be if we all had to read our favorite novels before knowing the gender of the author?

Susan Morse.

Susan Morse was educated at Williams College. She has worked as an actress in L.A. and New York and is the author of THE HABIT. She now lives in Philadelphia with her husband, David, and their three children, when they’re home from college.

March 4, 2015

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Alexandra Grigorescu: The Good, The Bad, and the Scary

I was surprised when someone casually described my debut novel, CAUCHEMAR, as a “women’s’ book.” It wasn’t said with any malice, and although I wondered whether it was meant to be dismissive, it didn’t make me feel bad. On the surface, it makes sense: Hannah is a young woman, who is torn between the lessons provided by two other women. She falls in love, and that love story is an anchor for the narrative as much as anything else. She’s a vulnerable character who experiences a painful, dangerous coming-of-age.

ECW Press, March 2015.

But CAUCHEMAR has also widely been called a Southern gothic, and to my great delight, quite a frightful read, and those labels are much closer to how I see it—without any gendered assignation about who wrote it, or who should read it.

I didn’t grow up reading “women’s books.” As a kid, I devoured Christopher Pike and Stephen King—and no, Carrie wasn’t my favorite of his books. I fell in love with the work of Ian McEwan, Jeffrey Eugenides, Michael Ondaatje, and Philip Roth. Bret Easton Ellis. Milan Kundera. Murakami. Pynchon. I also loved the work of Djuna Barnes, Barbara Gowdy, Margaret Atwood, Camilla Gibb, Ann-Marie MacDonald, and Donna Tartt.

I never thought there was a gendered line drawn in the sand between any of those authors. They just spun some darn good yarns. Yarns of all colors and shapes, sure, but isn’t the whole point of literature writ large to showcase different strokes for different folks?

It’s not a new issue. Meg Wolitzer wrote an excellent piece for the New York Times on the shoehorning of women’s fiction. My journey through academia revealed a male-heavy canon. David Gilmour sparked outrage when he declared in 2013 that “I’m not interested in teaching books by women,” as the CBC reported.

What is it about the work of female authors that so often squirrels them away in a separate category? Is it a quality of the writing? Is it a stereotype of domesticity? Or is it, maybe, a focus on squirmy, messy feelings?

Consider this recent article in the New York Times from psychiatrist and author Julie Holland. Women are seeking out medication that numbs traits hardwired into their biology. Instead, they’re opting to be calmer, more rational, less prone to bouts of pesky emotion—traits typically associated with men.

“Women’s emotionality is a sign of health, not disease; it is a source of power,” Holland argues. She adds: “Some research suggests that women are often better at articulating their feelings,” more empathic, and presumably better attuned to the feelings of their fellows—these are our evolutionary badges of honor, and they can manifest as a tissue fest or a sometimes inconvenient need to talk about feelings.

My earliest reading memories are of being spooked by some fine horror writers. It was inevitable that at some point in my writing life, I’d start peppering the pages with some scares of my own. And yet, it’s not uncommon for my loud and proud proclamation that I Love Horror Books And Movies to be met with total surprise, presumably because I’m a woman. And it’s not only men who are surprised.

What is the antithesis of stereotypical chick lit—with its pink covers, girlfriends brunching, and ladies finding Mr. Right—if not genre (which, let’s admit it, is sometimes equally stereotypical in its depictions of women as nervous Nellies who can’t help but take their tops off). What can be further away from a Sunday mimosa than monsters in the night?

Except that’s a very neat, and limited view of women’s lives. Think about the emotion that is instantly humanizing and recognizable on the page of any book, (regardless of genre) and the lifeblood of any horror book.

Fear.

In CAUCHEMAR, Hannah is young, emotional, and fallible. She wears her fear plainly, and hopefully in doing so, also puts the reader on edge. Hannah loves a man, deeply and frighteningly, and that is a source of both weakness and incredible strength. She faces unexpected motherhood, even as she’s coming to terms with being a daughter.

Hannah is an expression of many of the anxieties that I experienced at my own twenty-something crossroads: how to be independent, how to define my identity, how to be at ease with another person, within a community, or even with myself.

But that’s just a sound bite. The anxiety itself is just a rise in the road—facing it, dealing with it, trying to fit yourself around its senseless edges is a jagged peak where you’re barefooted and short of breath. Fear is silverfish in the walls, mosquitoes in your ears, a crow with rotting pincers. It is hateful stares on the streets, the dead crowding at your windows, and isolation you can’t escape. It is a threat against everything you love, which cuts deeper than any against yourself.

Anchor Books, Paperback Edition, March 1998.

This past year, women’s voices painted a troubling mosaic of experiences they’d kept secret. There’s an oft-cited Margaret Atwood quote that can seem generalized and reductive to those who don’t live its truth: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.”

There are many forms of abuse, whether overt or subtle: physical, sexual and psychological; intimidation; abuse of power; discrimination; threats; cyber bullying; sexism.

They describe the dimensions of a horror that would stick to you in a film too diffuse and yet enmeshed to rinse off, that would set your nerves on end, that would make you suspect each ring of a doorbell, each too-polished smile in a bar. The inescapable sort of horror that infects you, made all the more visceral for having been lived in ways small and large.

Think about pregnancy (and the potential of miscarriage), the violence and beauty of childbirth, and about offering your body as a source of food. Think about menopause. If the claim that women somehow feel more is true, think about the pain of watching a sick child, of caring for an elderly family member, of loving a partner. That domestic sphere is actually pretty crowded with complex stuff. Messy, un-dainty stuff.

So.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to write this post because it pushed me to explore how I feel as a female writer, and as a writer of what many would term a “women’s book.” I have to say—and it’s a boring, non-antagonizing, but hopefully heartening sentiment—I feel pretty good.

In part because, to me, books are still just books, regardless of the anatomy that put them together, and in part because whatever the female experience is, whatever it means to you as a writer or reader, it is legitimate, it is compelling, and it is full of riches to mine.

As for the literature that emerges? Let it sparkle like brunch bubbly if it so chooses, let it frighten and disturb, let it embolden and give voice. Don’t be afraid to delve into the dark parts of yourself, and don’t be afraid to let your readers feel the hint of tears still on the page. It is a complex story: to love, to fear, to wound, to nurture—to live as a woman.

Alexandra Grigorescu. (Photo by Maja Hajduk.)

Alexandra Grigorescu is the author of CAUCHEMAR (ECW Press, 2015). She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Toronto.

Her writing has previously been published in Echolocation and the Hart House Review. She’s also written about food, fashion, and other necessary things for blogTO and other Canadian sites.

She lives in Toronto, Ontario with her husband and a little black cat.

Say hello and talk books at Alexandra’s Goodreads page.

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from Jo Piazza: On the Passion of Nuns

I’ve spent a good portion of the past four years thinking about what it means to be a woman.

Open Road Media, September 2014.

It was four years ago that I began writing a book about American Catholic nuns.

For a long time, nuns have been thought of as something apart from gender, their vows of chastity and obedience, the fact that they will never become mothers, somehow separating them from other women.

It’s for that reason that no one ever talked about the facts that American nuns were the first feminists in this country, some of the first presidents of universities, hospital administrators and leaders of social justice organizations.

Nuns are some of the greatest women I have ever met. They’re strong and courageous. They love with abandon and allow their hearts to break each and every day for the people who live at the margins of our society. They act as mothers to children who desperately need them. They are tender and caring.

Nuns are women I am proud to know.

Editor’s Note: Looking for more on nuns from Jo Piazza? Check out this piece on Huffington Post Live, featuring an interview with some of the nuns from her book!

Jo Piazza.

Jo Piazza, is author of IF NUNS RULED THE WORLD, CELEBRITY INC. and LOVE REHAB. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Daily Beast, and Slate. Jo has also appeared as a commentator on CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and NPR. She is currently Managing Editor for Yahoo Travel.

March 3, 2015

International Women’s Week Guest Post from Marci Jefferson: Women in History Who “Made it Happen.”

As a historical fiction author, I approach every topic with one eye on the past. You may think this makes me look walleyed, and it might, but it also gives me a unique perspective on International Women’s Week.

Thomas Dunne Books, February 2014.

The theme this year is “make it happen,” and organizations everywhere are talking about how and what women are doing right now in the struggle for equality. This struggle has gotten buzz for the past hundred years or so, particularly from the time groups of very bold women started demanding the right to vote. But a few women stood up for themselves in bold ways much earlier. Here are a few examples.

My novels are fictionalized biographies, meaning my characters really lived, and their stories are dramatized accounts of historical events. Frances Stuart in GIRL ON THE GOLDEN COIN was a famous beauty living in France and England during the late 1600s. She happened to be distantly related to the English royal family, which landed her a position at the royal court, and into hot water. Her looks made her the target of amorous kings. Those kings had absolute power, and they didn’t appreciate it when she rejected their advances. To make matters worse, she depended on the favor of these kings to keep her paid position at court, which she needed in order to provide for her family. These days her case would likely be labeled as sexual harassment! But not only did Frances Stuart manage to survive, she won King Charles II’s respect and was selected as the model for Britannia on British coins. In an age before women’s rights, Frances Stuart relied on her strong personality and the power of persuasion to make her way in the world.

Marci with a Francis coin!

Another notable seventeenth century woman is Marie Mancini, whose amazing life inspired my second novel, ENCHANTRESS OF PARIS. Born in Rome, she was brought to France by her hated uncle, Cardinal Mazarin, advisor to King Louis XIV. The young king, also known as the Sun King, fell in love with Marie and was willing to tear his country apart to marry her. Unwilling to relinquish influence over the king to his niece, her uncle actually threatened to kill her. He was all-powerful, and she depended on him for her daily bread. In an age before women’s rights, Marie Mancini used street smarts and office politics to get out alive. She went on to practice magical divination during a century when condemned witches were executed. She published multiple books, rare for a woman in the seventeenth century. Later in life, she separated from her abusive husband, a powerful Roman aristocrat. Wives were legally subject to their husbands at that time, and the scandal had tongues wagging across Europe, but trail-blazing Marie managed to remain separated from him for the rest of her life. Why did she constantly strike out on her own and defy authority? According to her memoir, Marie valued her freedom.

Throughout history, women have struggled to live on their own terms, and these are just a few examples of how some “made it happen,” paving the way for us today.

Marci Jefferson.

MARCI JEFFERSON grew up in an Air Force family and so lived numerous places, including North Carolina, Georgia, and the Philippines. Her passion for history sparked while living in Yorktown, Virginia, where locals still share Revolutionary War tales. She lives in Fort Wayne, Indiana with her husband and children. This is her first novel. Visit her website at http://marcijefferson.com.

International Women’s Week: Guest Post from A.M. Dellamonica:Is it a Girl Thing?

This is going to be something of a meander.

The first step on the path was a conversation I’ve been having with my most recent writing class, about the uses a novelist can make of their television and movie viewing.

Tor Books, December 2015.

I write prose fiction, not screenplays. Novel and story-writing is what I teach at the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program. Yet I find myself resorting to using filmed examples of story constantly. This is a matter of necessity, occasioned by the nature of our collective cultural literacy. I’ve told a dozen people this week that I’m currently reading Barbara Tuchman’s incomparable The Guns of August, and Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black. I don’t think one of them knew either book, and I didn’t particularly expect them they would. There’s so much book out there, and we all have limited time.

At the same time, I’m re-watching most of the MCU movies, and taking in new shows as diverse as Gotham and Call the Midwife. I had a browse through the first half of Austin Powers not long ago. I can have a conversation about these properties just about anywhere I go.

As a writing instructor, I find it to be of immeasurable value, especially when discussing plot mechanics or character arc, to be able to refer to the body of work produced by Hollywood. I know that of any given class of fifteen students, at least ten will probably have seen whatever movie, show or iconic character I’m referencing.

And so I get my students to practice workshopping online by having them write sample critiques of movies (http://alyxdellamonica.com/2014/12/yippie-ki-yay-workshop-truckers/ – here’s my version of a praise-only crit of Die Hard), as if the films were works in progress by one of their classmates. The group gets to discuss these imagined novels without having to invest any of their valuable class time into a shared reading assignment.

Sure, if I had them for a year or more at a time, I’d get them to read all sorts of things–Lois McMaster Bujold, Connie Willis, John Irving, Italo Calvino, Nicola Griffith, Gemma Files–but I’ve got them for ten weeks, during which they have to generate fifty pages of original novel while keeping body, soul, job, and family obligations together.

Anyway, we were talking about this in class–reading, cultural literacy, the resource that is media–and I asked the group if they could think of negatives, for writers, of using TV and film as models for prose fiction. Once they’d batted this around a bit on their own, I advanced a shiny, new-to-me theory: media blunts our ear for written dialog.

Tor Books, June 2014.

This may seem counter-intuitive. Media characters talk all the time, right? But screenwriters know that their words are going to be delivered by talented performers, charismatic actors who will add all sorts of nuance, sound, and body-language to the mix. They’ll be well-lit, on a carefully dressed stage, and directed for maximum effect.

We prose-writing types have to do all of that with words. Screenwriters know they don’t have to bother with he-said/she-said stage directions, or suave descriptions of what their characters are doing as they jaw over the latest emotional beat in their story.

I see a lot of beginner work with overly melodramatic dialog, talking-heads-syndrome, and clumsy stage directions, and I think our diet of visual media is partly to blame.

As I said, though, this was a new-to-me theory. It isn’t something I’d put into words before, and though nobody offered a strong counter-argument at the time, I started minding it closely in my own viewing. Was it true? I’m a big fan of questioning my assumptions.

This brings me to Call the Midwife, and closer to the actual point of this essay, which is that as I listened closely to the dialog in everything I was watching, I noticed that this show seemed different from all my other media intake. There was something different about them. It wasn’t just that it was a period piece. It wasn’t the British accents, or even the lack of gunfire and homicide. I was listening, thinking about this assertion of mine, and trying to decide if the dialog was better, somehow, than the general run of the things I was watching. But it’s not–it’s decent TV dialog, well-written, well-performed but nothing special.

In fact, I concluded, Call the Midwife is no different structurally from any other one-hour “Of the Week” drama.

You know what I mean. The lion’s share of cop shows are Murder of the Week, right? With variations, obviously: gory corpse of the week (Bones), serial killer of the week (Criminal Minds), and cuisine tie-in homicide of the week (Hannibal.) House, M.D., meanwhile features a mysteriously ill patient of the week. Madmen? Pitch of the Week. Firefly? Caper.

Yes, this is a little bit of an oversimplification, but there are Fire of the week shows and lawsuit of the week shows and vampire of the week shows and Who’s Timothy Olyphant Gonna Shoot Today? of the Week shows. They are all, to some extent, built similarly to Baby of the Week, a.k.a. Call the Midwife.

What’s different is the content.

All of the other shows I’ve mentioned, no matter what their cast make-up is now, have their original genesis in guy shows: Police Story, Adam-12, The Night Stalker. Shows about white, straight, cisgendered dudes doing jobs in fields where such individuals, at one time, dominated. But Call the Midwife is an Of the Week show about a profoundly female thing. It’s women delivering babies born, exclusively, to women. As I continued to think about it, I came to wonder: is it the first? The only?

This, naturally, spawned other questions: are we moving into a place where all TV jobs can be done by people of any gender? As audience members, some of us are starting to demand exactly that. Which I love. But I wondered: are there no other fundamentally womanly things, besides childbirth, that have the high stakes and narrative variety required to support the demands of an episodic TV drama?

Tor Books, April 2012.

It was a somewhat uncomfortable place to end up. Childbirth and midwifery have this indisputably feminine component, but women have worked damned hard to show how much more we are, how many things we can do. Does it matter if I can find no other Girl Thing of the Week examples in a world where we do have all-woman cop shows, where Margaret Carter’s breaking into the spy business back in the midst of an imaginary superhero-infested 20th century?

As a community of people who love story, of people who write stories and consume them, writers and fans have been engaged in a wide-ranging conversation, online and elsewhere, about inclusiveness, diversity, and equality. We’re in a place where we’ve seen lots of progress, on the one hand, and are all too aware that we’ve got miles and miles to go. The scattering of data points and counter-examples and backlash is immense, and, for me at least, and the picture of the future that’s emerging can be awfully blurry. When something snaps into focus, as Call the Midwife did for me this week, it can be hard to decide how–even if–it’s significant. Maybe it just means I need to watch more soaps and sitcoms.

But I sense there’s a decent novel idea in there somewhere, once I’ve wrapped my head around it.

A.M. Dellamonica.

A. M. Dellamonica moved to Toronto, Canada in 2013, after 22 years in Vancouver. In addition to writing, she studies yoga and takes thousands of digital photographs. She is a graduate of Clarion West and teaches writing through the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program.

Dellamonica’s first ecofantasy novel, Indigo Springs, won the Sunburst Award for Canadian Literature of the Fantastic. Her most recent book, CHILD OF A HIDDEN SEA, was released by Tor Books in the summer of 2014; the sequel, A DAUGHTER OF NO NATION, will be out in November. Her works merge science and magic, they take biologists and physicists to worlds where they’re forced to confront enchantment, monsters and even, sometimes, pirates. She is the author of over thirty short stories in a variety of genres: these can be found on Tor.com, Strange Horizons, Lightspeed and in numerous print magazines and anthologies. Her website is at http://alyxdellamonica.com.