E. Kristin Anderson's Blog, page 4

September 18, 2015

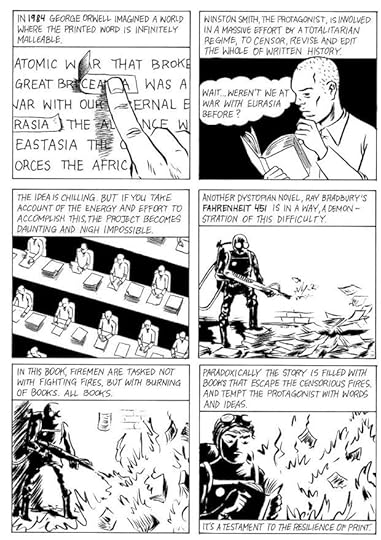

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Lorrie Sprecher: Want to Read Harry Potter in Arabic in Israel?

I’m currently doing research for a novel that will primarily take place in the West Bank of Palestine, so for banned books month, I’d like to talk about Israel. As a Jew with ties to Israel, I know this is a touchy subject. I am not suggesting that Israel is any worse than Hamas or the Palestinian Authority when it comes to banning reading material. But of course, like the United States, Israel calls itself a democracy.

Nahdet Misr Publishing Group, Fourth Edition, January 2008.

Inside Israel, books originating in Lebanon and Syria have been banned since 1939, before Israel was a state. It is a mandate-era ordinance from the First World War. According to Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, eighty percent of the books used by the Arab-speaking population in Israel come from publishing houses in Lebanon and Syria. Banned books include Harry Potter and Shakespeare. Many books of classical and modern Arabic literature, in Arabic, are only published in Lebanon and Syria, including the work of Mahmoud Darwish. Within the Arab world, only Syrian publishing houses publish Arabic translations of Hebrew literature, including the works of Amos Oz. Lebanon is the only country with publishers that translate children’s literature from English into Arabic.

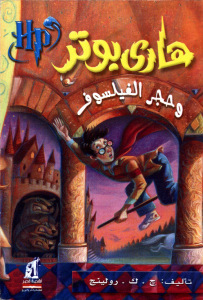

In 2008, the owner of Kull Shay, the largest supplier of Arabic language books in Israel, received a letter from the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor telling him that, under the Trade with the Enemy Ordinance of 1939, his license to import books published in an “enemy state” would not be renewed, even if he gets these book from other countries. Kull Shay has been importing books from Egypt for thirty years and Jordan for fifteen. Many of the books were published in Lebanon and Syria, but before 2008, this wasn’t a problem, and Kull Shay had the consent of the government censor. In a 2013 report, the Mossawa Center, an advocacy group for Arab citizens of Israel, notes that Israeli customs authorities held up a new version of a seminal work on Jewish thought because it violated the law regarding trade with the enemy. This Arabic language edition was printed in Beirut. The book was by Yehuda Halevi, a Spanish Jewish poet and philosopher who died in 1141. These are ongoing problems.

Feldheim Pub, Reprint Edition, August 2013.

In 2009, Israel’s Ministry of Education ordered the word “nakba” removed from a school textbook for Arab children. “Nakba” is the Arabic word for “catastrophe” and refers to Israeli independence in 1948 when 700,000 Palestinians were forced to flee their homes. Prime Minister Netanyahu has argued that using the word “nakba” is the same as spreading propaganda against Israel.

According to Max Blumenthal in GOLIATH: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel, applications to work in the Arab sector’s school system are read by a Shin Bet officer (an officer of Israel’s security agency) working inside the Ministry of Education, and teachers face punishment for contradicting the official Zionist narrative of independence. “To ensure total compliance with the state’s educational agenda, the Shin Bet operates a network of collaborators and informants in Arab schools, just as it does throughout Palestinian Israeli society.”

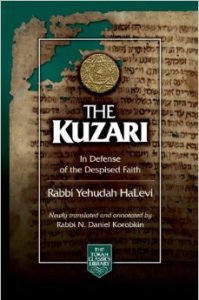

The Wall Museum.

In 2007, as Israel’s Minister of Education, Yuli Tamir, a liberal member of the Labor Party, approved a textbook for Arab children, which described Israel’s War of Independence as the nakba. The Arabic version of the textbooks for a third-grade course, LIVING TOGETHER IN ISRAEL: Textbook for Homeland, Society and Citizenship, contains the controversial line: “The Arabs call the war ‘nakba,’ a war of disaster and loss, while the Jews call it ‘The War of Independence.’” This is the only mention of the word “nakba” in any Israeli Arabic primary school textbook.

The text includes this description of that time: “Some of the Arab residents were forced to leave their homes and some were expelled, and they became refugees in the neighboring Arab countries. Some of them became refugees and were forced to move to other Arab communities in the State of Israel, because their villages were destroyed during and after the war.” The text also reflects the Jewish perspective on the creation of the state, including the fact that Arab parties rejected the 1947 United Nations partition plan for Palestine while the Jews accepted it.

The Wall Musem.

The adoption of this textbook caused an uproar in Israel, with then Likud Party Chairman Benjamin Netanyahu saying, “I can’t remember a greater absurdity than this in a decision made by an education minister in the State of Israel.” Yuli Tamir defended her decision on Israeli Radio, saying that Israel contains two populations, Jewish and Arab, and that “the Arab public deserves to be allowed to express its feelings.”

Most Arab and Jewish children study separately in segregated schools. The Hebrew version of the textbook does not contain the Palestinian version of the events of 1948. Jewish third-graders were considered too young to deal with conflicting narratives.

When Benjamin Netanyahu returned as Prime Minister, all copies of a high-school textbook, NATIONALISM: Building a State in the Middle East, were confiscated. It contained a reference to the Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi and said that some Palestinians “contended” that the 1948 expulsions were a form of “ethnic cleansing.” The Netanyahu government has also sought to criminalize public observances of the nakba.

The “Nakba Law” of 2011 authorizes the Finance Minister to withhold funding to institutions that commemorate Israeli independence as a day of mourning. In 2014, Netanyahu’s cabinet approved fourteen principles for a new nation-state bill. This proposed bill would change the “Jewish and democratic” definition of the state by subordinating the democratic component, making it secondary to the Jewish component. It states that the right to national self-determination in Israel belongs exclusively to the Jewish people. The enactment of this law could be used to justify widespread discrimination against Arab citizens of Israel.

The Feminist Press, June 2014.

Since I’m talking about the holy land, I’ll say that when it comes to banning books, people generally go with the Garden-of-Eden principle: knowledge is evil. Adam and Eve eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and are kicked out of the garden. Here in America, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, and the contributors to Wikileaks have all eaten from the fruit of the forbidden tree. Chelsea was kicked to jail, and now faces possible solitary confinement, and Edward was kicked all the way to Russia. We try to silence narratives based on things actually happening in the world, while we champion narratives that ignore other people’s experiences and actual events. Look at the Republican Party’s narratives on rape and climate change. And let’s not talk about teaching creationism in public schools.

Because we know each other by our stories, I’d like to mention the Wall Museum on Israel’s West Bank barrier (“the separation wall,” “the apartheid wall”) in Bethlehem. Israel has constructed a barrier separating Israel from the West Bank. The Arab Educational Institute has made posters of stories written by Palestinians and placed these on the wall. Currently there are one hundred stories written by Palestinian women and young people documenting life under occupation. You can read these stories in photographs on the AEI site: http://www.aeicenter.org.

Lorrie Sprecher.

Lorrie Sprecher is the author PISSING IN A RIVER (The Feminist Press, 2014), SISTER SAFETY PIN (Firebrand, 1994) and ANXIETY ATTACK (Violet Ink, 1992). She was a member of ACT UP/DC and has Ph.D. in English and American literature from the University of Maryland, College Park. She is also a musician and her song “It’s a Heteronormative World, No!” by her band Sugar Rat appears on a compilation put out by Riot Grrrl Berlin. She resides in Syracuse with her lovely dog Kurt.

September 17, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Trisha Leaver: The Banned Books that Built Me

I consider myself a well-adjusted adult and a contributing member of society. I have a house, a family, and a relatively steady income. I spend more hours running car pool then I do writing, sit on the school’s PTA board, and refuse to give out candy on Halloween to any teenager not dressed in a costume. In all actuality, I am the apple pie of America…boring to fault. I’m neither morally corrupt nor intractable in my ways, and yet I grew up on banned books. Devoured them. So, rather than speak about my passion for great literature or my firm belief that teens have the ability to “self-censor” what they read, I thought I’d share with you the banned books that literally built me.

Puffin Classics Paperback Edition, March 2008

THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN has the distinguished honor of being one of the most frequently challenged books in American history. Banned a short one month after its publication 1885, it has been criticized for being racially insensitive, oppressive, and propagating racism. You want to know what eleven-year-old me took away from HUCKLEBERRY FINN: compassion, loyalty, and the value of friendship. That I had to recognize my own faults and work hard to correct them. That the right path wasn’t always the easy one.

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE It is no secret that Maurice Sendak did not win over a lot of parents when his book first came out. Banned early on for promoting witchcraft and supernatural events, Sendak has been criticized for writing a book that was simply “too scary” and prompted bad behavior such as tantrums. Interestingly enough, this is the first book I recall my mother ever reading to me. And what did three-year-old me learn from that book? That my imagination was boundless. That even when I was alone, I’d never be lonely because I had the ability to dream and create entire worlds in my own mind…worlds that I would eventually pen out.

Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Reprint Edition, April 2014.

ARE YOU THERE GOD? IT’S ME, MARGARET/ BLUBBER/ FOREVER Judy Blume is one of the most frequently challenged authors, and yet I’m quite positive I owe 90% of my tween sanity to her. Whether I was being bullied, questioning the religion I was born into, curious about what the heck was going on in my body, or simply wanted to feel less awkward in my own skin, Judy Blume had a book for me. She’s pulled countless young women, myself included, out of some dark places, subtly assuring us that, eventually, things would be okay.

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD: Funny, I’ve read this book hundreds of times over the years and not once did I pick up on the very controversial fact that one of the items in her basket was a bottle of wine. In fact, the lesson I internalized from this beloved tale was simply not to walk in the woods alone or talk to strangers. Two valuable life lessons in my opinion!

Speak, Reprint Edition, September 1988.

THE OUTSIDERS: I got handed this book by my tenth grade English teacher and still remember sitting up at night in bed, refusing to put it down. It’s been banned for glorifying drug and alcohol abuse amongst teens and violence. Interesting how after reading this book a gazillion times as an “impressionable” teen, I didn’t grow up to be a raging alcoholic or a drug addict. Nope…not even close. What I took away from THE OUTSIDERS – what my English teacher correctly assumed I’d identify with – was a kid struggling to find his place in the world, raging against the idea that his life was pre-determined at birth, defined by where he lived or how much money he had.

I can keep going, list dozens of other books I loved as a teen—and still love today—that some parent or school board has deemed morally reprehensible. To them, I simply shake my head for I guarantee I’m a better person, a kinder individual for having read those books.

Trisha Leaver.

Trisha Leaver lives on Cape Cod with her husband, three children, and one rather disobedient black lab. She is a chronic daydreamer who prefers the cozy confines of her own imagination to the mundane routine of everyday life. She writes Young Adult Contemporary Fiction, Psychological Horror and Science Fiction and is published with FSG/ Macmillan, Flux/Llewellyn and Merit Press. Her YA Contemporary novel, THE SECRETS WE KEEP, was named one of the best YA novels for summer by Teen Vogue and received starred reviews from VOYA Magazine and School Library Journal. To find out more about her, please visit her website at www.trishaleaver.com

September 16, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Amy McNulty: On Censorship & Manga

While it’s true that it’s rare to find me without a book within reach, that book is almost as equally likely to be a graphic novel, or more likely, a volume of manga (Japanese comics) as it is a YA book. Ever since I fell in love with SAILOR MOON in middle school, I’ve been drawn to the art style and stories in these comic imports, so much so that I sometimes forget the criteria for censorship is different in Japan than it is in America, and what doesn’t bat an eye there might prove more alarming to parents in the West. It’s no surprise, then, that people have attempted to ban certain manga on American shores.

TokyoPop, October 2004.

Japan doesn’t have the same attitude that the U.S. has toward nudity, for example—at least not when the nudity isn’t sexual. Public nude bathing (typically, but not always, with the same gender) is a part of Japan’s onsen traditions. It’s no surprise, then, that manga aimed at children can feature naked kids or teens from time to time—when bathing or transforming into a superheroine, for example. It’s usually not detailed—they may as well be wearing a skintight suit most of the time—but it’s enough to usually get the English translations here a “for teens” or “for older teens” rating at the very least.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t the “I found pictures of nude characters in my child’s Japanese comic book!” argument that sparked the idea of banning a manga in North American shores that surprised me. When I was a teen, there was this one manga that I came across at just the right age. MARMALADE BOY by Wataru Yoshizumi mostly focuses on high school friendships and romantic entanglements. After her parents return from a vacation to Hawaii, teenager Miki Koshikawa is flabbergasted when her parents cheerfully announce they’re getting a divorce and that they’re spouse-swapping with another Japanese couple they met on their trip. In fact, they got on so well that no one’s moving out; Miki’s new step-mom and step-dad are moving in to their house, along with their teenage son. Strangely, Miki’s the only one who doesn’t take this well. Even her new step-brother—handsome and now going to Miki’s school, naturally—is strangely blasé about the whole affair.

TokyoPop, April 2002.

If I ever read a manga I knew would be banned, MARMALADE BOY was not it. But in 2005, one parent in Florida wanted the books removed from her local library after her 11-year-old checked them out because it involved couple swapping. I read the other manga title she wanted removed, Miwa Ueda’s romantic high school drama PEACH GIRL, as a teen as well, and I do actually remember it being more risqué (and more melodramatic) than MARMALADE BOY. (But both of these titles were rated for teens, 13+, on the back covers.) Still, topics such as drugs and date rape—the reasons why the parent objected to PEACH GIRL—shouldn’t automatically mean a book is made unavailable for mature teens who can handle it, just as it’s no reason why YA books dealing with these topics should be kept out of all teens’ hands in a community because some families don’t want their children reading these books.

Sex, drugs and couple swapping aren’t the only reasons manga has been banned. As you might have guessed, violence is another factor. Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata’s DEATH NOTE, a popular manga first published in Japan in 2003 and in the U.S. in 2005 is a compulsive read about Light Yagami, a high schooler who finds a reaper’s notebook. He discovers that whenever he writes a name in the notebook and pictures that person’s face, the person will die, and he can even dictate the method in which he or she dies. Light actually displays many symptoms of a psychopath to begin with—not that he’d harmed anyone until that point, but he considers himself detached from and smarter than most of the population. In true Dexter style, he decides to use this power “for good” by only executing criminals who otherwise escape the justice system—only his plans go far further than Dexter’s. He dreams of a crime-free utopia because criminals never know how this “god of death” will strike them down. He’s actually quite effective for a time, but of course, law enforcement can’t let this stand, and the manga becomes a duel between Light and L, the brilliant, socially awkward detective assigned to track down the killer—and discover how on earth he’s committing the killings in the first place.

VIZ Media, October 2005.

It’s a compelling story, but like the Dexter books and TV series, it’s had some real world ramifications among those exposed to it. Even though it’s rated for “older teens” (typically 16+), not every reader who grabs it off of the shelves is going to be that old or mature enough to handle it. In Japan, it was published in a magazine that targets a middle school and even older elementary school demographic, and the violence isn’t overly graphic, both factors that probably kept the manga from being rated for adults here. Still, there have been incidents around the world of kids writing their own “death notes” in homage to the series, which is problematic when you consider America’s culture of school violence in particular. Parents in a New Mexico school district even went so far as to call for a district-wide ban on the manga in public school libraries in 2010, although a committee unanimously voted against the ban.

With DEATH NOTE tied to at least half a dozen real-world incidents of teens writing their own “death notes,” and even to a murder case in Belgium, it seems like a scary influence on children—and I can understand some of the hesitance to have it readily available to teens. However, one of the committee members ruling on whether or not to ban it in the New Mexico school district, Tom Genne, succinctly stated the benefits of leaving such material available: “High school age kids do grapple with questions about justice and morality, and whether civilization, or the societies of which they are a part of, are making good decisions.” That is the true theme of the manga—and to ban it for older teens ready to contemplate things of this nature because younger children and unbalanced individuals have been taking the wrong message from it isn’t the right course of action. Monitoring what your own children are consuming—and what they’re ready to handle—is.

When reading material produced in and for another culture, it’s too easy to examine it from your own pre-conceived notions of what’s appropriate, especially where teens and kids are concerned. I think the manga translation industry already does a good job of rating each title according to how appropriate the material is for youth in American culture, so anyone concerned can do the research or simply turn over the book and see the age group that should be reading it.

Instead of calling for the ban of any title, it’s up to parents to decide what they think is appropriate for their own kids—not what they want other people’s kids to read. On the other hand, I suggest parents read a title themselves and decide if maybe it has more value than it seems to based on plot synopsis alone. I read manga all through my middle and high school years (and beyond), and I can tell you all it did was make me a better and more imaginative writer with a passion for stories in all genres.

Amy McNulty.

Amy McNulty is a freelance writer and editor from Wisconsin with an honors degree in English. She’s the author of the YA romantic fantasy NOBODY’S GODDESS (Book One in The Never Veil Series) and a contributing writer for Anime News Network.

September 15, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Jacqueline Kolosov: ON BANNING The Scarlet Letter

According to many critics, Hawthorne should have been less friendly toward his main character, Hester Prynne (in fairness, so should have minister Arthur Dimmesdale). One isn’t surprised by the moralist outrage the book caused in 1852. But when, one hundred and forty years later, the book is still being banned because it is sinful and conflicts with community values, you have to raise your eyebrows. Parents in one school district called the book “pornographic and obscene” in 1977. Clearly this was before the days of the World Wide Web.

Bantam Classics, March 1981.

I may be cheating in choosing Nathaniel Hawthorne’s THE SCARLET LETTER as the banned book that has left its own scarlet letter—or deep mark—in my heart. When I read the novel in high school in the 1980s, it was part of the curriculum, though I was privileged, yes, truly privileged to grow up in a community and within a family that encouraged me to “read” and seek truths outside of the proverbial box. In middle school, we read a novel called JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN about a young man whose consciousness we enter; and consciousness is all that remains of someone who lost all of his senses—except touch—as a soldier in World War I. Yes, I could have written about this novel, for like several other war novels on the list, among them CATCH-22, JOHNNY GOT HIS GON, too, was banned; and honestly, my wonderful teacher—who cleared the classroom of desks and let us all sit on a rug on the floor—was also highly unusual, even for my school. In many places, he would never have held onto his job. But I digress—

In searching for “the most banned books of all time,” I found THE SCARLET LETTER along with MOBY DICK (another favorite) and NATIVE SON and FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS there, too. I chose to write about Hawthorne’s novel for its enduring timeliness despite the fact that it was published in 1850 and set in the middle of the seventeenth century Puritan New England. As those of you who’ve read it know, Hester Prynne and her lover conceive a child “out of wedlock.” Hester bears that child, a daughter whom she names Pearl, and in so doing, she is branded a “harlot” by her community, forced to spend time in prison, and after her release, finds herself on the very margins of her society where she nonetheless manages to earn a living as a seamstress. Despite the fact that Hester lives a “moral” life—and I hope I don’t have to define that term except by saying that she is a good, loving, compassionate person who works and keeps house and takes loving, loving care of her child—the community ultimately tries to take that child away from her. Why? Because Pearl is too much a free spirit. Raised in a liminal space, both literally and figuratively, for she is the child of a scarlet woman who grows up on the edges of the wilderness—or what remained of it in Salem at the time, Pearl is too exuberant, strange, and alive, and these qualities scare people.

Hester’s plight, then, or her predicament, and that of her child, speak to me strongly; and they remain all too timely today. In many parts of the world, women are not only branded and imprisoned for bearing children outside of married. They might even be murdered. I just read an astonishingly good story by Amy Gustine about an Israeli woman who strays into Gaza in search of her son, who was imprisoned by Hamas. In the process, this woman is sheltered by a Muslim woman and her son who are also sheltering yet another woman—really a girl—who is about to give birth. Her brothers, the Muslim woman tells the Israeli woman, would kill her if they knew the truth. And the killing would go unquestioned because of the circumstances. Family honor/shame is tribal.

Hawthorne was a member of the literary establishment when he published THE SCARLET LETTER, and he came from formidable Puritan stock. Both of these aspects of his identity are central to why THE SCARLET LETTER was well-received (despite what Henry James called its “indefinable purity and lightness of conception,” central qualities of a great work of art.

Meredith Hall, an American writer, published a memoir entitled WITHOUT A MAP, and it’s a book that would be extraordinary to set in dialogue with Hawthorne’s masterpiece. Hall grew up in the 1950s in New Hampshire. She was in high school when she had sex, and if I remember it was her first time and the circumstances were confusing, and she became pregnant. Within her community, the stigma was so intense—the shame—that she was forced to wait out her pregnancy in hiding at her father’s house. (Her parents were divorced.) Once she gave birth, the baby, a boy, was immediately taken from her. The doctor treated her as if she was a, well, a slut. He made her feel ashamed. And so did her family and everyone else who knew about her actions. And she was ashamed. More than this, however, she pined for her child and found it impossible to reintegrate into society—unlike Hester Prynne. Hall wound up finishing high school far from home, and then she found her way to Europe and from there she walked all the way to Africa. She walked and walked ‘without a map’ because, in large part, she was lost without her child. Or to be more precise: she was lost and confused by the uncertainty and confusion of his conception, birth and disappearance. The most extraordinary part of the memoir, though, is that this child, some eighteen years later, finds his way back to her—and becomes a part of her life, and a part of the lives of the two sons she later had. It’s miraculous, really, and it enables Hall to heal; though the fact is, her son had a most devastating growing up, and yet he managed to be able to love and to forgive…

This post is far more associative than linear, but I trust the reason I singled outTHE SCARLET LETTER is becoming clear. Roughly 165 years ago, Hawthorne published a novel about a woman who was punished and shamed and marginalized because she fell in love with someone (and I won’t get into his story and all that it entails or we’ll be here well into October). Bottom line: she loved. She had the courage to love. And after she was branded, she had the courage to continue to love, channeling that love into her child.

Remarkably, astonishingly, terrifyingly,THE SCARLET LETTER has been banned, to the best of my knowledge, for two reasons: 1. For its open treatment of adultery which was a really dicey subject to tackle in the 19th century America unless one tackled it with condemnation. (And think about it: even Tolstoy, roughly Hawthorne’s contemporary, killed off his heroine, Anna Karenina, who commits suicide by throwing herself under a train. Anna, too, committed adultery, though her circumstances were radically different. And she is a beautiful character, and her destruction is terrifying—a terrible loss. I don’t think ANNA KARENINA was ever banned. I don’t think the Russians banned novels dealing with adultery. No, it was a political novel that could get one into trouble both before and after the Revolution.

So Hawthorne’s novel was banned for treating adultery, yes; but more than this, it was banned because of Hawthorne’s love for and compassionate treatment of Hester Prynne. Somehow a whole bunch of readers totally missed the point in thinking that Hester should have suffered more or been more severely treated. And those readers, I’m afraid, are the same people—Oh, I cringe at labeling others, but for the sake of concision I must—who ostracized Meredith Hall. The same but different. I suppose, there’s the issue of breaking a moral law within a society that so terrifies us as human beings. It’s threatening. Laws are what allow us to live as a society. (Yet laws are sometimes made to be broken. Or: nothing is ever or rarely ever black and white.) Adultery was and still is threatening. Except that Hester Prynne’s husband was presumed dead, and the man with whom she conceived a child wasn’t married. But still, adultery was the issue for the BAN THAT BOOK group of readers. Hester Prynne, like so many other strong heroines, is a transgressive figure. She breaks laws. She lives outside the norm. She loves.

And love is the most powerful force in the world, I hope, isn’t it?

Jacqueline Kolosov.

Jacqueline Kolosov has published several novels for teens, among them THE RED QUEEN’S DAUGHTER (Hyperion) and more recently, Along the Way and the forthcoming PARIS, MODIGLIANI & ME (Luminis Books). She is also a poet and writes literary fiction and nonfiction. Her web page/blog is www.jacquelinekolosovreads.com. Jacqueline grew up in Chicago and now lives in west Texas with her family and a menagerie of animals including a Spanish mare, 3 dogs, 2 cats, and a Jersey wooley rabbit who would like to join the circus.

September 14, 2015

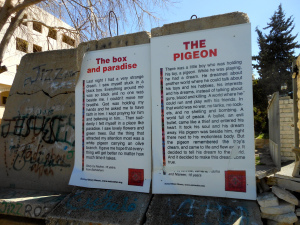

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Tom Kaczynski: The Resilience of Print

Tom Kaczynski.

Tom Kaczynski is an Eisner and Ignatz nominated cartoonist, designer, illustrator, writer, teacher and publisher based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His comics have appeared in Best American Nonrequired Reading, MOME, Punk Planet, The Drama, and many other publications. Beta Testing the Apocalypse is out now from Fantagraphics. His next book, TRANS TERRA, will be out this fall. When he’s not drawing he runs Uncivilized Books, where he publishes smart comics & graphic novels from all over the world.

September 13, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Cathy Clamp: It was a pleasure to burn…

Sixty-five years ago, a legendary science fiction author penned the six words that open this post as the beginning of a novella. He simultaneously opened the eyes of millions to what Banned Books Week really is, and what it’s meant to prevent. Ray Bradbury first published FAHRENHEIT 451 as a short story titled “The Fireman” in 1950. A few weekends ago, at the height of the 2015 back-to-school frenzy at a Barnes & Noble, I bought another copy. I wasn’t born when it was conceived in Bradbury’s mind . . . didn’t first read it until it was assigned in high school when it was already 20+ years old. But it changed my life.

Simon & Schuster, Reprint Edition, January 2012.

Until I met Guy Montag in the pages of that story, I’d never conceived a world where books weren’t everywhere. I grew up in a pre-computer world. My home was filled with books of all shapes and sizes. I spent my summers not playing in the sun with the other kids, but curled up in the coolness of my bedroom with one book or another. We had a dictionary on one shelf in the den, just the right height for a child to reach for. We were encouraged to “go look it up” when we couldn’t pronounce a word, or didn’t understand what it meant. It sat on the shelf next to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Student edition. Around the corner in the next room were faux leather-bound classics: ROBIN HOOD, ALICE IN WONDERLAND, 20 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA, TARZAN.

When I first heard of Banned Books Week as a child, I asked my mother why people would ban books. She thought for a moment, sitting there in the kitchen, tapping a finger on her latest romance novel. She told me, “I guess it’s because words have power. Power of truth and power of lies. What one person believes is truth, another will believe is a lie. Books entertain. But they also challenge and enlighten and confuse. That’s why all books need the chance to be.”

It made sense to me and when a teacher (and I’m embarrassed to admit I don’t remember which teacher it was) brought to class a list of books that had been banned and urged us to check them out of the library, I did. They weren’t books I would have normally read. I liked mysteries and fantasies. These were heavy, deep books and yes, they confused me; challenged me. Many I didn’t like. Even classics that are lauded for their greatness. But I read them because someone had once decided they weren’t worthy of existing. I wanted to prove that person, whoever they were, wrong.

It was a pleasure to burn.

The hero of FAHRENHEIT 451 was a child of an imaginary future, yet eerily, an adult in our present. His world is the one we live in, which makes the book all the more poignant. Flat screen televisions covered his walls. Only three walls, instead of four, because he couldn’t afford the $2,000 for the last one. Reality shows filled their house with noise. His wife Mildred, Millie, wore earbuds and carried her smart phone around the house, glued to her programs. And books? They were what her husband destroyed for a living. Nothing more.

Guy was dissatisfied with his life. He just never knew it. But one day a young girl asked if he was happy. He realized he wasn’t. It felt inherently wrong to start houses on fire just because they had books inside. Then, when a woman hoarding books refused to leave them, and instead chose to stay and burn up with them, he snapped.

I won’t give away what happened, because I discovered to my surprise (and I admit, a certain horror) that there were dozens, perhaps hundreds of people that I personally know…who have never read this book. Three co-workers, my same age, had never heard of it. Their children hadn’t either. It’s no longer mandatory on many required reading lists. Ironically, it IS a book that has been censored and challenged by several school districts.

I’m not sure whether to laugh or cry…

Tor Books, August 2015.

My own book, FORBIDDEN, was the reason I was at the Barnes & Noble during back-to-school week. It was just released and I was signing it for readers who wandered by. I had to drive nearly 150 miles to attend the book signing. All of the other signings set up by my publisher were about the same distance away from my home. Why? Because there are no bookstores in my town. In fact, there isn’t a bookstore within 50 miles of my house, unless you count the ever-shrinking section at Walmart.

The fact that I’m a national bestselling author is a dirty little secret where I live. People check out my books at the library, but would never admit to reading them because they have (shhh!) magic. There are shapeshifters and vampires and wizards who are people. They’re both good and bad. They live, they love, they screw up and recover. The evil people are truly evil. But the good people are truly good. Yet even the idea of magic is evil here, so the librarian doesn’t bother to log the book into the computer. She puts them on the shelf without a pocket in front, without a slipjacket, because they’ll just disappear anyway, down into a black hole where the people who would likely be at the front of the line to burn it live. Then she asks for more once they all disappear. Maybe they are being burned in someone’s fireplace. Maybe an unemployed Guy Montag is out there, a fireman just waiting for the alarm to light the igniter…I stay here because the people aren’t evil. They’re good people, nice people and I believe people can grow. Anyone can learn tolerance and reading is the easiest way to learn.

I haven’t read all the books on this year’s Banned Books list, but I started by buying Bradbury’s classic, along with 1984 by George Orwell. A teenager recently told me 1984 gave her nightmares. I laughed, but then realized I shouldn’t have. Both of these books aren’t cautionary tales of a horrible future anymore. They’re real. They’re just regular life.

We created the future. Science fiction has become science fact.

And as bookstore after bookstore closes, as reality television becomes more important than words scribbled on a page, Banned Books Week may no longer become necessary, because there will be nothing left to ban.

I’ll leave you with an elegant truth from the pages of FAHRENHEIT 451, written in 1950, that is meant to educate and enlighten you. And maybe, for all those on Twitter and Facebook right this second, frighten you just a little bit:

“If you don’t want a man unhappy politically, don’t give him two sides to a question to worry him; give him one. Better yet, give him none. Let him forget there is such a thing as war. If the government is inefficient, top-heavy, and tax mad, better it be all those than that people worry over it. Peace, Montag. Give the people contests they can win by remembering the words to more popular songs or the names of state capitals, or how much corn Iowa grew last year. Cram them full of non-combustible data, chock them so damned full of ‘facts’ they feel stuffed, but absolutely ‘brilliant’ with information. Then they’ll feel they’re thinking, they’ll get a sense of motion without moving. And they’ll be happy, because facts of that sort don’t change. Don’t give them any slippery stuff like philosophy or sociology to tie things up with. That way lies melancholy.”

Read. I beg you. Even if you don’t buy FORBIDDEN, buyFAHRENHEIT 451. Even if you’ve read it before, long ago. Buy it again. Give it away to someone young, one who can change the future. Remind them, and yourself, how that last little line, not of banning and censorship—but of neglect and disinterest— is so very easy to cross.

Cathy Clamp.

Cathy Clamp has written paranormal romance and urban fantasy in partnership with C.T. Adams. Clamp and Adams hit the USA Today bestseller list with their Sazi and Thrall series. They are also the authors of the Blood Singer series, published under the name Cat Adams.

FORBIDDEN is Cathy Clamp’s first solo novel. It returns to the world launched in HUNTER’S MOON.

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Émilie Gleason: My Childish Opinion On Copyrights

I have this feeling that in France, we advocate self-censorship: Generally people know what is right or lawful, and avoid every topic that could lead to a conflict. It is at least what I’m now invariably told, since I wasn’t aware of copyrights when drawing my very first comic. My experience isn’t with banishing a book for its religious or political points—no, I just drew a mouse.

2DCloud, 2015.

To feature Mickey Mouse was completely instinctive. I mean, I grew up with him, my five senses saturated by songs, stuffed toys and coloring books. Then I realized that showing a famous character was reassuring, and demystifying it was surprisingly witty.

Publication changed the situation—we no longer tell a story for oneself but for the public, which has mates, big kids and sharks: copyrights. We change the name and the nose, the dialogues and the ending. We go from an alpha story to a beta story, equally interesting, I guess, but unrelated to the original. More generally, I have this feeling that each year, a number of true ideas are ebbing away for fear of reprisals, our brains being educated to enact what we want to hear, to remain ethically correct in order to satisfy everybody. It’s tasteless. In France we miss loudmouths pursuing their ideas and shouting what everyone really think, without our fabled, weepy complaints. (A sample of my self-censorship: I really hesitated to write this last sentence.)

Émilie Gleason.

Émilie Gleason is a Strasbourg, France-based student in illustration. Her first comic book, SALZ & PFEFFER, was published in English by 2DCLOUD publishers and represents the greatest experience in her life so far. She is now working on several tutorial-dream projects for her last-year diploma. She still hopes she could drive a semi-truck within North America in the future, but in the meantime you can find her work at emiliegleason.com.

September 12, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Stephanie Wardrop: A Plea for (Critical) Reading before Banning a Book

I read Courtney Summers’ recently banned book SOME GIRLS ARE almost in one sitting. I didn’t read it so quickly – despite having plenty of other things to do – because it was such a fun read. It was anything but fun. In fact, most of it was unpleasant at best, disturbing at worst. But that doesn’t mean anyone else should be prevented from reading it, as many students were this summer due to one school district’s response to one parental complaint.

St. Martin’s Griffin, January 2010.

The novel was one of two choices for summer reading for incoming freshman in honors English at West Ashley High School in Charleston, South Carolina – until one parent complained and it was removed from the short list of choices. I won’t go into the whole sequence of events; they have been widely documented and you can read about them here. Suffice to say that as a writer and a teacher of literature, I am against the banning of books, especially when a book is banned due to a single complaint, while as a mother I am sympathetic to the desire to protect kids from potential dangers, though I am not quite sure exactly what those imagined dangers are in this case.

Melanie McDonald, the mother does not make clear in the letter Charleston newspaper The Post and Courier what she objects to in the book that she deems “trash.” She mentions the depiction of a skeevy math teacher who likes to look ay female students’ legs when they go up to the chalkboard (I remember at least one of those in my student days), “body shaming about the size of the lead character’s breasts (I either missed this part of the book myself or did not see it as “body shaming”) and a “sexual reference so explicit” she would not quote it in her letter (I’m guessing it’s the line about “flicking” a girl’s “bean,” which we as readers are meant to find gross and insulting and evidence that the speaker is a Neanderthal misogynist). She says that educators are entrusted to “mold our children” – and tells her readers “make no mistake that high school students are children.” She declares that she could not get past page 74 of the book (at the time of her writing the letter- she finished it later) and deems SOME GIRLS ARE “trash” and “completely inappropriate for any high school student.”

Many others have commented on the obviously moralism in calling the book “trash” and the injustice in allowing one parent to decide what is appropriate for all high school students, and they have done so quite eloquently. In this post, I would like to better understand what makes the book so “inappropriate” and on what grounds, exactly, Ms. MacDonald objects to SOME GIRLS ARE. Does she fear that the events depicted will expose students for the first time to drug use, alcohol, bullying, violence, and suicide? Does she feel it will influence students to want to behave like the characters in the novel? If her anxiety lies in the former, then I think, as many have argued, most freshmen students have been exposed to these sad facts of teen life long before they pick up Summers’ book, if not in their actual lives then through exposure by other media (television, movies, news stories, the internet).

But if the fear and distaste lies in the latter – a concern that students will want to emulate those depicted in the novel – I can’t help wondering how careful a reader Ms. MacDonald is, and how little faith she has in her daughters’ peers’ critical reading abilities. Even if she had stopped reading at the first 74 pages and not continued to the end, surely Ms. MacDonald recognized that the novel present a cautionary tale, one with a moral, even, that could please almost everyone, far more than it depicts a titillating look at the lifestyles of the rich and adolescent. I could examine what happens in those first 74 pages, but it will serve my point as well to focus instead on a “close” or critical reading of the first paragraphs alone, contained in the preface, titled “Before.”

The preface all but spells out the lesson the main character, Regina, will learn. It reads:

HALLOWELL HIGH:

You’re either someone or you’re not.

I was someone. I was Regina Afton. I was Anna Morrison’s

best friend. These weren’t small things, and despite what

you may think, at the time they were worth keeping my

mouth shut for.

It seems important to me to consider this introductory passage – like the rest of the novel- as descriptive rather than prescriptive. When Summers says through Regina “You’re either someone or you’re not,” she’s describing the way the social hierarchy works at the very dysfunctional Hallowell High, not the way it should work anywhere on the planet. But a lot of American readers will recognize their schools as being similarly plagued by mean girls and in-groups. The second paragraph tells us that our narrator, Regina, was once “someone” because she was “Anna Morrison’s best friend;” she had an identity in the in-group only in relation to queen bee Anna Morrison. We learn that something has happened that Regina never spoke of in order to maintain her elevated status. Because she is speaking in the past tense, we know she lost that status and that whatever she kept her mouth shut about, she shouldn’t have.

As a teacher, it’s my job to walk students through a critical reading like the brief one presented above, and I can only assume that the teachers at West Ashley High School would have done the same had they been allowed to. They might even have pointed out the sad irony in the main character’s name, Regina, who is no longer a queen and slowly realizing the awful things she did as one of Anna’s flunkies to earn that crown.

In those first 74 pages, we learn that Regina loses her status in the in-group because Kara, a girl on the fringes of that group, advises her not to report it when made Anna’s boyfriend sexually assaults Regina at a party while Anna is passed out drunk a few feet away from them. Kara offers this counsel for self-serving reasons: so that she can get into the group, become Anna’s new bestie, and “freeze out” Regina, and that’s exactly what happens. No one believes that Regina did not sleep with her best friend’s boyfriend and they ostracize and bully Regina as Regina, under Anna’s command, ostracized and bullied others. Regina later learns that one girl, whom she had liked very much before Anna had bid her to torment her, even attempted to kill herself because of their bullying.

Is Regina a victim in the treatment she receives? Yes, but she is also a pretty horrible person, and the book shows this rather unflinchingly without ever hinting that she deserves to be assaulted because she was a horrible person. Perhaps it is this complexity, Summers’ refusal to present a moral absolute here in the novel, that some readers find troubling. Few characters, including Regina, are either wholly good (perhaps Michael and Liz are) or bad (I’d slot Anna and possibly her ex-boyfriend in this category). In the rest of the novel, Regina begins to come to terms with what she’s done and it’s not an easy path – there’s not even much of a clear resolution in the end, as there rarely is in real life. It’s an ugly story, filled with violence between privileged, popular girls and “teachers [who] never go out of their way to notice anything” (45), probably because they feel powerless to do so. Nonetheless, for those readers looking for a moral, SOME GIRLS ARE certainly presents a few: “Don’t be mean—it may come back to you, karmically.” And “don’t sell your soul for popularity.”

There are so many conversations that a book like this could start in the classroom, ones that might finally get to real, close-to-home concerns for the students, and it is a shame that this opportunity was forfeited because of one complaint. Ironically, perhaps, though, the banning drew a great deal of attention to the book and is garnering it hundreds of new readers who may otherwise never have discovered it. The sites Book Riot and Stacked solicited donations of copies of the book and, as of this writing, have collected 830 copies and $600 in donations.

This turnaround hardly marks a triumph against censorship, though. The only thing that could end banning and censoring books is reading carefully and critically, which is exactly what a high school English class is designed to do.

Stephanie Wardrop.

Stephanie Wardrop is a YA writer whose SNARK AND CIRCUMSTANCE series is an Amazon category bestseller. When she’s not reading or writing, she’s hanging out with her family, teaching writing and literature at Western New England University, and herding cats.

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Erika T. Wurth: Assimilation Makes Us Soooo Happy

In 2010 the Arizona state legislature, ring-led by then-Superintendent of Schools Tom Horne and then-State Senator John Huppenthal, banned seven books (specifically), and outlawed any classes that “promoted the overthrow of the United States, fostered ethnic resentment or treated students as members of an ethnicity rather than as individuals.”

West End Press, November 2007.

When this first came down the social media pipeline, it joined the many issues that I filed in my head under what the actual fuck, America. But as it continued to play out and I learned more about what they were doing, what they had done, and how extensive it was, I realized how close to home this could be. What I learned was that they were banning any book that addressed identity. And then I realized that that included mine. Of course, the only book I had out at the time was a collection of poetry called INDIAN TRAINS that only a handful of Natives and my mother had read (she keeps it in her living room next to the baby mocs my Auntie beaded for my sister). I can only imagine what they would have thought of my novel, with its drug dealing pregnant F-bomb dropping protagonist. When people began to respond to my realization, the reaction was generally, COOL DUDE! I wish I’d written a book that was banned! But it didn’t feel cool. It felt hateful. My book, and any book by a person of color, a woman, a queer person or, it turned out Shakespeare for fuck’s sake, could be seen as a text overly-invested in identity.

There is such double-speak here. I remember after a particularly brilliant reading by a friend (another Native poet) a colleague of mine reacting to her reading by rolling his eyes and stating that identity was sooooo persuasive. I think that because her work evokes emotion (and it certainly did for her audience that day), that made that scholar uncomfortable. But more than anything, what made him uncomfortable was hearing lovely, poetic language used to describe the fact that on her reservation, children were suiciding, and that there were reasons for this. Reasons he was complicit in, simply for being a citizen of this country. What amused me about his reaction, and what always amuses and eventually angers me about this idea that identity is only something that people of color, or queer people, or woman have is how blatantly untrue it is. Identity is something that everyone has. DUH. And that if one is from the dominant group, the only difference is that it is so big, it is invisible. I also think about how sacred identity is to straight white males. How carefully they guard it, any hint that they might be like women, or not straight is met, often, with violence. So I’m pretty sure that whatever was deemed appropriately identity-less in Arizona still had plenty of what anyone could identify as identity. Just white, straight, male and therefore so big as to be invisible identity. Indeed, the school board, after this ban, approved only one book by a Latino author despite the fact that independent research illustrates that courses and books that revolve around Latino identity improve student achievement for Latino students.

Or was it despite?

Curbside Splender, September 2014.

All of this reminds me of Rand Paul’s recent statement that if Native Americans would only be forced to assimilate, we would be so much happier. Yes. Enforced assimilation… such as, perhaps, a decimation of 90% of our population and subsequent sending of the remainders of us off to boarding schools in the United States and in Canada where we were punished, often physically, for speaking our languages? Perhaps enforced assimilation like sequestering us on tiny plots of land? Perhaps something like that, would make us soooo happy. Thanks, Rand Paul. You’re right. Assimilation makes people really happy.

All sigh-tastic sarcasm aside, I think this is the point. Rand Paul, Arizona’s Tom Horne, and others of this ilk know perfectly well what this is all about. It’s about suppression under the guise of the right kind of wording. Because here’s how it works: when you see someone like yourself in any public medium you begin to think you can do the things that those people are doing. You begin to realize that there is absolutely no reason why you can’t achieve. They know this. This is their point. If they can take us out of art, we have no power. We do not see ourselves. We will go back to slaving and dying. And you know what? There is no reason for that. It makes everyone unhappy. It makes for an imbalanced, capitalistic, earth-destroying world. So no thanks, Rand Paul.

There is a semi-happy ending to this story. The ban was reversed. But the fight is still on. There are school boards still fighting to ban any reflection of a diverse self, to keep things as they are. The big presses still publish predominately white, straight men. Children of color are still underrepresented in high education.

Sooooo happy.

Erika T. Wurth.

Erika T. Wurth’s novel, CRAZY HORSE’S GIRLFRIEND, was published by Curbside Splendor. Her collection of poetry, INDIAN TRAINS, was published by The University of New Mexico’s West End Press. A writer of both fiction and poetry, she teaches creative writing at Western Illinois University and has been a guest writer at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in numerous journals, such as Boulevard, Drunken Boat, and Southern California Review. She is represented by Peter Steinberg. She is Apache/Chickasaw/Cherokee and was raised outside of Denver.

September 11, 2015

Banned Books Month Guest Post from Kay Kendall: The Fears that Lurk Behind Banned Books

Let’s look at the fundamentals behind the urge to ban books. At rock bottom it is always fear that propels people and institutions to ban books. And what those people and institutions fear most is loss of control.

Ideas expressed in books can spur readers to change their views from those approved by authorities. Whoever wields control gets to say what should be thought, how people should behave, what should be worshipped, how people should love.

Stairway Press, July 2015.

When different ideas begin to be expressed that undermine those strictures, then those ideas must be squelched before they gain popularity and wreak havoc among the populace. Different ideas are dangerous. Books must be banned.

Yet here’s the irony. The very action of banning a book makes it more tantalizing. Forbidding ideas draws more interest. This forces those in authority to crack down harder. Ultimately, the game can only be won by the authority—a parent, a government, a church—by using force. That’s how dictatorship can grow in homes, nations, and religions.

I studied European and Russian history in college and grad school, and now I write historical mysteries. My approach is always to take the long view, to see what humanity has been up to down through the ages. The urge to ban ideas expressed in written materials is as ancient as books themselves. In fact, the word censor originated in ancient Rome with a magistrate who supervised public morals. It was deemed an honorable function, based on earlier ideas established in ancient Greece.

Here are a few examples from different eras with which I am most familiar. You will see that the fear of losing control lies behind all these.

Signet, Reprint Edition, October 2009.

Renaissance Italy

During the Renaissance, the Tuscan city of Florence experienced a great burst of creativity—in art, literature, and architecture. Then the Vatican sent a Dominican priest named Savonarola to the city at the request of the ruling Medici family. Soon the priest began warring with the Medicis and decrying their extravagance in art, literature, furniture—in short, anything fancy or excessive that took people’s minds off religion. Savonarola held huge bonfires in the town square and encouraged citizens to throw all their splendid items including masterpieces written by Ovid, Dante, and Boccaccio. Soon the Vatican turned against Savonarola, excommunicating him and burning him alive in 1497. Shortly thereafter the Vatican authorities banned the writings of the priest himself. Clearly a struggle for control was carried out by banning on both sides.

This episode is so famous that the phrase “bonfire of the vanities” has gone down the years as a reference point. The bestselling novel written in 1987 by Thomas Wolfe carries that name, as does the film adaptation starring Tom Hanks (1990).

“Banned in Boston”

Banned in Boston is a term I grew up with in the 1960s. The phrase has roots that reach far back, to the beginning of the Massachusetts Bays Colony founded by censorious puritans in the 1600s. The phrase became common in the late 1800s when the city of Boston developed stringent laws censoring lewd and lascivious books, plays, and other works of art. Renowned people whose works were “banned in Boston” include Boccaccio (again!), Walt Whitman, George Bernard Shaw, H.L. Mencken, Aldous Huxley, Eugene O’Neill, Sinclair Louis, Ernest Hemingway, and William Faulkner. Even The Everly Brothers’ song “Wake Up Little Susie” was banned in Boston in 1957. I have noted only the very tip of the iceberg of censorship created in Boston and encourage you to do an Internet search for more examples. Of course, the consequence was that sales of works deemed lurid and naughty increased outside that puritanical city. Some twentieth century authors were proud of being banned, and their publishers advertised the banning proudly.

Vintage, Reprint Edition, October 2011.

The Soviet Union

The Russian empire ruled by the tsars was overthrown by Vladimir Lenin and his communist revolutionaries in 1918. While tsarist control over literature had been strict, control by the communist government in the successor state—called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or simply the Soviet Union—was far more pervasive and intense. When Joseph Stalin became head of both the Communist Party and the Soviet state after Lenin’s death, control of every form of human expression in art, literature, and science became absolute. Failure to comply meant an artist or scientist would risk either prison in Siberia or the ultimate punishment—death. Gradually a culture of samizdat grew up in the land. That is the Russian word for self-publishing. Writers passed around their pages to trusted readers so that censorship could be avoided. Poets memorized all their volumes of poetry in order to keep their literature alive.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Soviet society experienced a “thaw” in censorship. This emboldened Boris Pasternak to submit his novel DOCTOR ZHIVAGO to the Soviet censors in 1956. They turned it down. A copy of the manuscript was smuggled out of the Soviet Union by an Italian communist and published abroad. Pasternak’s novel was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957 But Soviet authorities pressed him to refuse it. He died in 1960, and his family accepted his Nobel posthumously for him in 1988.

And the moral is . . .

I have discussed only a few of thousands of historical examples of book banning—ones that fascinate me most. History is important because it illustrates patterns. It is said that human nature never changes, and for me these examples show that the war over freedom of thought and expression will be forever waged.

When your child’s teacher wants to ban HUCKLEBERRY FINN from the school’s library, I hope you will remember these examples. Please consider whether you should try to control your child’s thinking—or should you instead try to help him or her understand competing points of view? There is a wealth of ideas available in our world today. Being able to choose wisely among them is a critical skill for anyone to develop.

Kay Kendall

Kay Kendall writes atmospheric mysteries that capture the spirit and turbulence of the 1960s. A reformed PR executive who won international awards for her projects, Kay lives in Texas with her Canadian husband, three house rabbits, and spaniel Wills. She earned degrees in Russian history and studied the Russian language in the Soviet Union, which accounts for her being a student of the Cold War and aficionado of Russian culture. Her book titles show she’s a Bob Dylan buff too. DESOLATION ROW (2013) and RAINY DAY WOMEN (2015) are part of her Austin Starr Mystery series.