National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Julie Marie Wade: It Could Have Happened So Many Ways

It Could Have Happened So Many Ways. But it happened this way.

I was twenty, not quite twenty-one. I was about to be a senior in college. My best friend was about to get married and move with her husband to California. I was about to realize I didn’t love men the same way that I loved women.

The fact was, we were all on the cusp of something, and some of us liked the word cusp—how one syllable contained a hard and soft together, forming a perfect equilibrium.

Bywater Books, Reprint Edition, November 2014.

But an actual cusp was more dubious. We weren’t sure how we felt about the feeling.

I was just home from my first and only study abroad. Seeing more of the world had the unintended effect of making me feel smaller, less than before I left.

*

Before London, there was a plan. My father printed many pages of information concerning PhD in Psychology programs. He left these pages in a tidy binder on my desk.

Their arrangement this way made them seem even less desirable, made me feel even smaller.

Sheaf is a good word. I like it almost as well as cusp. It is soft on both sides with a little rise in the middle. Its slant-rhyme is yeast, which seems significant in this context.

But my father had not left me a sheaf of applications. He had left me a stack. The pages were no longer warm, since they had been printed many months before.

On my desk, I also noticed a lean manila envelope, my lone piece of mail after four months away. Both my parents said EN-ve-lope, like envy or environment. I said ON-ve-lope, like placing a bet on something.

*

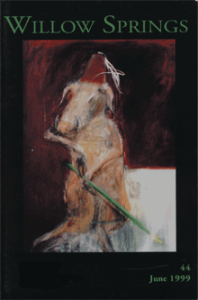

“Do you know anything about this?” I ask my mother—this book called Willow Springs. The cover sports a mysterious creature wearing a Shriner’s hat and holding, either a thick blade of grass or a green magician’s wand.

I decide it’s a blade because I prefer the word blade to the word wand. This preference is part of my ongoing romance with the long A, but I don’t discuss this kind of thing with my parents.

“I told you I don’t want you ordering from The Amazon,” she replies. By this, she means a local company of newly national reach, not a particular member of a tribe of warlike women. My mother herself is something of an Amazon, but shorter, I think, than Amazons typically are.

“I didn’t order it,” I say. “It just came.”

“Well, then, maybe it’s from a secret admirer.” Her thick, mascaraed lashes flutter. This is meant to be ironic, since my mother is rapidly losing hope I’ll ever have one of these.

*

Willow Springs, Issue 44, June 1999.

What is immediately apparent is that I would rather read Willow Springs than work on my psychology applications. In fact, I would rather read Willow Springs than do almost anything else. While I’ve been taught out of anthologies for most of my life, this one is different. I don’t even recognize it as an anthology at first because 1. No author or editor names appear on the front cover 2. There is no subtitle instructing me as to the time periods, countries, and literary movements represented by this anthology and 3. The poems and stories the book contains are not prefaced by long, dry, fact-laden forewords. The poems and stories are allowed, at last, to stand alone.

And then this: I am so engrossed in reading that I drop the book (Butter fingers, my mother would say, a metaphor as sensuous as it is accurate), and when I pick it up, I notice a section called Contributors’ Notes: So-and-So lives or So-and-So works or So-and-So is the recipient of X awards. All the verbs are present tense. I may have gasped, or I may have added the gasp to my memory in retrospect. Regardless, this is what shocks me most: These So-and-Sos, these writers of poems and stories whose work has been collected here, are not only smart and interesting and accomplished people. They’re…wait for it…ALIVE!

*

Fifteen years in the future (prolepsis), it shocks me most to remember how shocked I was by the fact that living writers of poems and stories were publishing in places like Willow Springs and then going on about their collective business of not being dead. It shocks me second-most to realize that Willow Springs was not at that time an example of a literary journal to me, a one among many. Rather, it was the only literary journal to me—a sui generis compendium of contemporary writing that appeared in my mailbox without precedent or explanation. I didn’t know the “44” meant there had been 43 previous editions or that, as I’m writing this Whatever-You’d-Call-It today, in the spring of 2015, Willow Springs has just released their 75th issue. The journal is celebrating “Forty Years of Poetry and Prose.”

This is the thing about cusps: We so often can’t see that we’re on one until we’ve fallen off.

A Midsummer Night’s Press, March 2014.

I read Issue 44 of Willow Springs thoroughly, in order, cover to cover, the way I have never read (will never read) a literary journal again. There are so many of them, and there is so little time by comparison. I skip around now. I look for names of writers I recognize, titles that catch my eye. I always flip to the poetry section first. But back then (analepsis), I didn’t know there were more of these to come. I didn’t recognize any writer names. I couldn’t name any of my preferences yet. So of course I couldn’t have imagined that in just two years, I’d be one of the two poetry editors for another literary journal based in Washington State—the Bellingham Review. That I’d be a graduate student in creative writing instead of psychology. That the other poetry editor would be my partner in more than poems, the woman I would marry someday.

A few days later, a letter arrived from Eastern Washington University. We hope you’ve received your complimentary copy of Willow Springs by now. Just think: as a graduate student in our Master of Fine Arts program, you could contribute to the literary legacy that has kept Willow Springs going strong for a quarter-century now…

I’m paraphrasing. I didn’t keep the letter, but I did make some notes. Eastern Washington University? Master of Fine Arts program? This entire period of my life seems to have been surrounded by question marks. I went to the library and got on The Internet. I may have even got on The Amazon. I was feeling about as risky and adventurous as I had ever felt.

This is another thing about cusps: if at all possible, it’s better to leap than to fall.

*

It could have happened so many ways—my not becoming a psychologist, or a secretly admired heterosexual.

The moral of this story is not that LITERARY JOURNALS SAVE LIVES, though if you’re affiliated with a literary journal, feel free to borrow this slogan, print it on t-shirts and wrist bands, or wave it like a flag.

But I do believe that LITERARY JOURNALS CHANGE LIVES, or at least that this particular journal arriving at this particular time changed mine—and indisputably for the better. I opened the book and found a hallway instead of a page. Every title was a door. Every door I opened took me into a room where I wanted to stay, closer to a person I wanted to be. Where once I had been ajar, I was now agape. Everything spoke to me like an oracle, both prophetic and summative.

Surely Jennifer Oakes must have been speaking for me when she wrote the poem, “The Listener.” Her speaker says, “I begin each day blank as an uncut key.” How else to describe my own experience as I entered this book and as I moved through the world? I was a key in need of cutting.

Her speaker describes “eight thousand/ voices all asking in different ways/ whether they must eat alone at the table/ of their hearts forever.” This was a question I had been asking without words for most of my life, but in Oakes’ poem, the words were extended to me at last like an offering. What a gift to be able to name what is felt at last!

They were also a version of an ars poetica, a term I would later learn, describing the panoply (surely eight thousand constitutes a panoply) of other writers and artists who made literature and art in response to this essential human question of love and loneliness.

*

I was going to have to tell my parents that I wasn’t going to graduate school in psychology. In their language, this was going to sound like a declaration of personal and professional failure. Before too long, I was going to have to tell my parents that I wasn’t going to marry the man I began dating my senior year. In their language, this was going to sound like a suicide note.

Sarabande Books, November 2011.

Jennifer Oakes named precisely the pained anticipation I felt, tottering there on the cusp of self-disclosure, in the final couplet of her poem: “It would take fire or breaking glass to tell them/ the poppy, the apple, the vein.”

In the kitchen, my mother was chopping vegetables. My father was reading the paper. I held Willow Springs in my hand like the panoply it was, meaning both “a striking array or arrangement” and “that which covers and protects.”

Then, I faltered on the cusp. Without precedent or explanation, I said, “Words mean more to me than anything else.”

They looked up. They looked at each other and then at me. I tried again. “Listen,” I said, and for a few moments, we were all present on the same page, walking together down the same hall, standing outside the same door.

In other words, it happened this way: My parents fell silent, and I read them a poem.

*

The Listener

I begin each day blank as an uncut key,

but in the shower I start hearing neighbors

twelve blocks over

washing the body of their mother.

It comes through the pipes, comes tight

as the lasso of a stutter, dragging

its word from the tongue’s falling house.

I hear the advice of psychics

when I pick up my telephone, of eight thousand

voices all asking in different ways

whether they must eat alone at the table

of their hearts forever.

Of mannequins ashamed of their severed wrists,

the shot star gone unseen, calling out

to the dust of old planets that it is coming,

and trees unbinding storms from their branches.

But hardest are the seeds of the bloodfruit.

Their words are so red they enter

only once and desperately at knifepoint.

They believe they are alone in their cardinal

tongue, sanguine and praying.

It would take fire or breaking glass to tell them

The poppy, the apple, and the vein.

—Jennifer Oakes, reprinted from Willow Springs Issue 44, June 1999

Julie Marie Wade.

Born in Seattle in 1979, Julie Marie Wade completed a Master of Arts in English at Western Washington University in 2003, a Master of Fine Arts in Poetry at the University of Pittsburgh in 2006, and a PhD in Interdisciplinary Humanities at the University of Louisville in 2012. She is the author of WISHBONE: A Memoir in Fractures (Colgate University Press, 2010; Bywater Books, 2014), winner of the Lambda Literary Award in Lesbian Memoir; WITHOUT: Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2010), selected for the New Women’s Voices Chapbook Series; SMALL FIRES; Essays (Sarabande Books, 2011), selected for the Linda Bruckheimer Series in Kentucky Literature; POSTAGE DUE: Poems & Prose Poems (White Pine Press, 2013), winner of the Marie Alexander Poetry Series; TREMOLO: An Essay (Bloom Books, 2013), winner of the Bloom Nonfiction Chapbook Prize; WHEN I WAS STRAIGHT: Poems (A Midsummer Night’s Press, 2014), selected for the American Library Association’s Over the Rainbow List; and the forthcoming collections, CATECHISM: A Love Story (Noctuary Press, 2016) and SIX: Poems (Red Hen Press, 2016), winner of the AROHO/To the Lighthouse Prize. A regular book reviewer for The Rumpus and Lambda Literary Review, Wade teaches in the creative writing program at Florida International University. She is married to Angie Griffin and lives in Dania Beach.