Gary R. Ryman's Blog, page 9

August 16, 2013

More you might be a Redneck Firefighter if….

The soda machine in the station is actually loaded

with Genesee, Iron City or insert low end beer here.

Four guys get off a piece of apparatus and three of

them are related (whether they know it or not).

The portables still have extendable antennas.

The “donations” from filling pools with the tanker

are a major source of department income.

The Memorial Day Chicken Barbeque at the station is

the social event of the year.

A call comes in at 7:00 AM on the first day of deer

season and the only one who moves are the deer.

One of the first line pieces still has coats, boots,

and helmets hanging from a rack on the side.

The port-a-pond doubles as the town swimming pool on

hot summer days.

with Genesee, Iron City or insert low end beer here.

Four guys get off a piece of apparatus and three of

them are related (whether they know it or not).

The portables still have extendable antennas.

The “donations” from filling pools with the tanker

are a major source of department income.

The Memorial Day Chicken Barbeque at the station is

the social event of the year.

A call comes in at 7:00 AM on the first day of deer

season and the only one who moves are the deer.

One of the first line pieces still has coats, boots,

and helmets hanging from a rack on the side.

The port-a-pond doubles as the town swimming pool on

hot summer days.

Published on August 16, 2013 14:08

August 10, 2013

Dilbert and the Fire Department

The cartoon “Dilbert” wouldn’t be so funny if it

weren’t so situationally accurate which long ago led me to develop one of

“Ryman’s Rules” relating to the strip. This one is not a law of physics, but a

sociological paradigm which states that: Morale of any organization is

inversely proportional to the number of Dilbert cartoons hanging on the

walls. With that in mind, how many of

these comic strip worthy situations have you seen or experienced?

Pulling into a fire scene with an assignment to lay

a supply lie and finding the hose bed empty, the line having accidentally laid

during the response. Funny how that never happened when we rode

the back step; oh well.

Watching a hose bed turn into silly string when the

pump operator charges the wrong line—the one not pulled.

Getting ready to drain the drop tank and finding the

drain placed on the uphill side.

Extending the “blue line” with yellow hose and

handing it to a new crew who then asks for the “yellow line” to be charged. The reason I hate color coded lines.

Scanning mobile and portable radios—the important

information always gets cut off. Enough

said.

Pump operators who think “100 pounds is good enough

for everything.”

Did you ever notice the same five guys who always have

to leave for work the minute it’s time to wash the rigs and hose after a run?

The company responding for RIT that calls out with

five and shows up with a driver and four juniors.

The officer, who when in charge of a training night,

waits until everyone arrives and then says “so what do you guys want to do

tonight?”

Fire Police who drive like Jeff Gordon for some

reason assuming it is critical they be the first on scene—in order to direct

traffic.

The citizen who on an annual basis, waits for the

windiest day of the year to burn trash, resulting in a 5 acre brush fire, and

then acts surprised when he gets yelled at.

Looking at the personal vehicles parked during the

inevitable call on the afternoon of the first day of buck season and marveling

that there is more firepower present than that possessed by the entire local

police department. Actually true most any

day for rural departments.

The local cop who on an automatic fire alarm offers

to shoot the lock off the door instead of waiting for the apparatus or key

holder. His offer was turned down.

The guy with more state class patches on his sleeve

than a Sergeant Major has stripes—who won’t go inside.

The guy with the two door subcompact car and a blue

light bar so big it extends feet beyond the sides of the car. So big you wonder if the car will rotate

when the lights are turned on.

The guy who carries three pagers and two portable

radios—all on his belt at the same time. Note:

The three above are often the same guy.

The brush fire in a two acre field with only a

single solitary tree located right in the center—which the brush truck driver

hits while backing up.

You know you’re really in trouble when three pieces

of apparatus, all responding to the same call, reach the same intersection; and

one turns left, one goes straight, and the third turns right.

Last, but certainly not least, (insert favorite personal activity here) with your significant other

is invariably interrupted by the pager.

weren’t so situationally accurate which long ago led me to develop one of

“Ryman’s Rules” relating to the strip. This one is not a law of physics, but a

sociological paradigm which states that: Morale of any organization is

inversely proportional to the number of Dilbert cartoons hanging on the

walls. With that in mind, how many of

these comic strip worthy situations have you seen or experienced?

Pulling into a fire scene with an assignment to lay

a supply lie and finding the hose bed empty, the line having accidentally laid

during the response. Funny how that never happened when we rode

the back step; oh well.

Watching a hose bed turn into silly string when the

pump operator charges the wrong line—the one not pulled.

Getting ready to drain the drop tank and finding the

drain placed on the uphill side.

Extending the “blue line” with yellow hose and

handing it to a new crew who then asks for the “yellow line” to be charged. The reason I hate color coded lines.

Scanning mobile and portable radios—the important

information always gets cut off. Enough

said.

Pump operators who think “100 pounds is good enough

for everything.”

Did you ever notice the same five guys who always have

to leave for work the minute it’s time to wash the rigs and hose after a run?

The company responding for RIT that calls out with

five and shows up with a driver and four juniors.

The officer, who when in charge of a training night,

waits until everyone arrives and then says “so what do you guys want to do

tonight?”

Fire Police who drive like Jeff Gordon for some

reason assuming it is critical they be the first on scene—in order to direct

traffic.

The citizen who on an annual basis, waits for the

windiest day of the year to burn trash, resulting in a 5 acre brush fire, and

then acts surprised when he gets yelled at.

Looking at the personal vehicles parked during the

inevitable call on the afternoon of the first day of buck season and marveling

that there is more firepower present than that possessed by the entire local

police department. Actually true most any

day for rural departments.

The local cop who on an automatic fire alarm offers

to shoot the lock off the door instead of waiting for the apparatus or key

holder. His offer was turned down.

The guy with more state class patches on his sleeve

than a Sergeant Major has stripes—who won’t go inside.

The guy with the two door subcompact car and a blue

light bar so big it extends feet beyond the sides of the car. So big you wonder if the car will rotate

when the lights are turned on.

The guy who carries three pagers and two portable

radios—all on his belt at the same time. Note:

The three above are often the same guy.

The brush fire in a two acre field with only a

single solitary tree located right in the center—which the brush truck driver

hits while backing up.

You know you’re really in trouble when three pieces

of apparatus, all responding to the same call, reach the same intersection; and

one turns left, one goes straight, and the third turns right.

Last, but certainly not least, (insert favorite personal activity here) with your significant other

is invariably interrupted by the pager.

Published on August 10, 2013 05:50

Dilbert and the Fire Department

The cartoon “Dilbert” wouldn’t be so funny if it

weren’t so situationally accurate which long ago led me to develop one of

“Ryman’s Rules” relating to the strip. This one is not a law of physics, but a

sociological paradigm which states that: Morale of any organization is

inversely proportional to the number of Dilbert cartoons hanging on the

walls. With that in mind, how many of

these comic strip worthy situations have you seen or experienced?

Pulling into a fire scene with an assignment to lay

a supply lie and finding the hose bed empty, the line having accidentally laid

during the response. Funny how that never happened when we rode

the back step; oh well.

Watching a hose bed turn into silly string when the

pump operator charges the wrong line—the one not pulled.

Getting ready to drain the drop tank and finding the

drain placed on the uphill side.

Extending the “blue line” with yellow hose and

handing it to a new crew who then asks for the “yellow line” to be charged. The reason I hate color coded lines.

Scanning mobile and portable radios—the important

information always gets cut off. Enough

said.

Pump operators who think “100 pounds is good enough

for everything.”

Did you ever notice the same five guys who always have

to leave for work the minute it’s time to wash the rigs and hose after a run?

The company responding for RIT that calls out with

five and shows up with a driver and four juniors.

The officer, who when in charge of a training night,

waits until everyone arrives and then says “so what do you guys want to do

tonight?”

Fire Police who drive like Jeff Gordon for some

reason assuming it is critical they be the first on scene—in order to direct

traffic.

The citizen who on an annual basis, waits for the

windiest day of the year to burn trash, resulting in a 5 acre brush fire, and

then acts surprised when he gets yelled at.

Looking at the personal vehicles parked during the

inevitable call on the afternoon of the first day of buck season and marveling

that there is more firepower present than that possessed by the entire local

police department. Actually true most any

day for rural departments.

The local cop who on an automatic fire alarm offers

to shoot the lock off the door instead of waiting for the apparatus or key

holder. His offer was turned down.

The guy with more state class patches on his sleeve

than a Sergeant Major has stripes—who won’t go inside.

The guy with the two door subcompact car and a blue

light bar so big it extends feet beyond the sides of the car. So big you wonder if the car will rotate

when the lights are turned on.

The guy who carries three pagers and two portable

radios—all on his belt at the same time. Note:

The three above are often the same guy.

The brush fire in a two acre field with only a

single solitary tree located right in the center—which the brush truck driver

hits while backing up.

You know you’re really in trouble when three pieces

of apparatus, all responding to the same call, reach the same intersection; and

one turns left, one goes straight, and the third turns right.

Last, but certainly not least, (insert favorite personal activity here) with your significant other

is invariably interrupted by the pager.

weren’t so situationally accurate which long ago led me to develop one of

“Ryman’s Rules” relating to the strip. This one is not a law of physics, but a

sociological paradigm which states that: Morale of any organization is

inversely proportional to the number of Dilbert cartoons hanging on the

walls. With that in mind, how many of

these comic strip worthy situations have you seen or experienced?

Pulling into a fire scene with an assignment to lay

a supply lie and finding the hose bed empty, the line having accidentally laid

during the response. Funny how that never happened when we rode

the back step; oh well.

Watching a hose bed turn into silly string when the

pump operator charges the wrong line—the one not pulled.

Getting ready to drain the drop tank and finding the

drain placed on the uphill side.

Extending the “blue line” with yellow hose and

handing it to a new crew who then asks for the “yellow line” to be charged. The reason I hate color coded lines.

Scanning mobile and portable radios—the important

information always gets cut off. Enough

said.

Pump operators who think “100 pounds is good enough

for everything.”

Did you ever notice the same five guys who always have

to leave for work the minute it’s time to wash the rigs and hose after a run?

The company responding for RIT that calls out with

five and shows up with a driver and four juniors.

The officer, who when in charge of a training night,

waits until everyone arrives and then says “so what do you guys want to do

tonight?”

Fire Police who drive like Jeff Gordon for some

reason assuming it is critical they be the first on scene—in order to direct

traffic.

The citizen who on an annual basis, waits for the

windiest day of the year to burn trash, resulting in a 5 acre brush fire, and

then acts surprised when he gets yelled at.

Looking at the personal vehicles parked during the

inevitable call on the afternoon of the first day of buck season and marveling

that there is more firepower present than that possessed by the entire local

police department. Actually true most any

day for rural departments.

The local cop who on an automatic fire alarm offers

to shoot the lock off the door instead of waiting for the apparatus or key

holder. His offer was turned down.

The guy with more state class patches on his sleeve

than a Sergeant Major has stripes—who won’t go inside.

The guy with the two door subcompact car and a blue

light bar so big it extends feet beyond the sides of the car. So big you wonder if the car will rotate

when the lights are turned on.

The guy who carries three pagers and two portable

radios—all on his belt at the same time. Note:

The three above are often the same guy.

The brush fire in a two acre field with only a

single solitary tree located right in the center—which the brush truck driver

hits while backing up.

You know you’re really in trouble when three pieces

of apparatus, all responding to the same call, reach the same intersection; and

one turns left, one goes straight, and the third turns right.

Last, but certainly not least, (insert favorite personal activity here) with your significant other

is invariably interrupted by the pager.

Published on August 10, 2013 05:50

August 3, 2013

Fire Archaeology: Still Salvaging After All These Years

The

stories of most major fires concentrate on the immediate impact; the deaths and

injuries which resulted. Just over 40

years ago, a fire occurred which caused no deaths or serious injuries, the

impact from which is still being felt.

Just after midnight on July 12, 1973, fire broke out on the sixth floor

of the National Personnel Records Center in Overland, Missouri.

Construction

work on this building to hold military service records was completed in

1956. When the original studies were

conducted during the design phase, conflicting advice was received from

archivists and personnel at other government records retention facilities. Some strongly recommended the inclusion of

automatic sprinklers and others argued against.

Not surprisingly, since we are talking about this fire forty years

later, the anti-sprinkler forces won. Storage

of paper records in folders and boxes packed on metal shelves and file cabinets

filled the building—a massive fire load.

The

fire response exceeded 6 alarms. The

interior attack was abandoned at 3:15 AM that morning due to deteriorating

conditions, but the exterior attack continued for days. On the 14th, firefighters

re-entered the building to begin final extinguishment and overhaul on the sixth

floor; a task complicated by partial structural collapse of the roof. By the 16th of July, a single

company remained on scene.

Following

fire extinguishment began a salvage operation which continues even today. Computer tapes and microfilm records were

among the early transfers to an off-site facility. All six floors of the building experienced

substantial water damage, and the recovery of water soaked records was a

massive operation. Wet records were

re-boxed and the escalator railings used as a slide to move them to the ground

floor for transport. Setting up a

temporary facility at the nearby Civilian Personnel Records Center, plastic

milk crates, eventually 30,000 of them, were used for open shelf drying, but a

better solution was on the horizon.

A

vacuum drying chamber was located at the McDonnell Douglas Aircraft plant in

St. Louis. The chamber was originally

constructed for space simulation as part of the Apollo moon program. Once archivists confirmed the technology

worked, two additional chambers at the Sandusky, Ohio NASA facility were located

and used as well. Wet records were

placed in the plastic milk crates, which were stacked nine high on wood

pallets, and the records loaded into the chamber, which was sealed. Air was evacuated from the chamber and the

temperature lowered to freezing. Hot dry

air was then introduced until the wetted materials reach 50 degrees F. Depending upon how wet the material was,

multiple cycles could be needed to dry the records. With a single chamber capable of holding

2,000 milk crates, nearly eight tons or 2000 gallons of water could be removed

during a run.

The

charred and burned materials recoverable from the sixth floor created another

challenge. Luckily, this material was

not disposed of following the fire, but stored as “B” files, as improvements in

technology have made the information from some of these materials usable

again. Today a team of thirty uses the

latest restoration techniques to recover information from these documents. Working

in latex gloves, this group represents an archival CSI for documents; cleaning

mold and debris and utilizing digital technology, scanners, and specialized

software, some information from burned sections can be revealed and

recovered.

This

information remains important. Requests

are received from veteran’s families for information needed to obtain various

programmatic government benefits along with on-going work by genealogists and

historians. The meticulous work the

recovery team does, like archaeologists unearthing an ancient village filled

with information, is critical in helping these servicemen.

Sprinkler

protection became an important component for all such government facilities

following this fire; a lesson learned like many others, through disaster. While we will likely never know how many

records were lost in the fire, the cause of which remains undetermined, that

recovery and restoration continues forty years later is nothing short of

miraculous.

stories of most major fires concentrate on the immediate impact; the deaths and

injuries which resulted. Just over 40

years ago, a fire occurred which caused no deaths or serious injuries, the

impact from which is still being felt.

Just after midnight on July 12, 1973, fire broke out on the sixth floor

of the National Personnel Records Center in Overland, Missouri.

Construction

work on this building to hold military service records was completed in

1956. When the original studies were

conducted during the design phase, conflicting advice was received from

archivists and personnel at other government records retention facilities. Some strongly recommended the inclusion of

automatic sprinklers and others argued against.

Not surprisingly, since we are talking about this fire forty years

later, the anti-sprinkler forces won. Storage

of paper records in folders and boxes packed on metal shelves and file cabinets

filled the building—a massive fire load.

The

fire response exceeded 6 alarms. The

interior attack was abandoned at 3:15 AM that morning due to deteriorating

conditions, but the exterior attack continued for days. On the 14th, firefighters

re-entered the building to begin final extinguishment and overhaul on the sixth

floor; a task complicated by partial structural collapse of the roof. By the 16th of July, a single

company remained on scene.

Following

fire extinguishment began a salvage operation which continues even today. Computer tapes and microfilm records were

among the early transfers to an off-site facility. All six floors of the building experienced

substantial water damage, and the recovery of water soaked records was a

massive operation. Wet records were

re-boxed and the escalator railings used as a slide to move them to the ground

floor for transport. Setting up a

temporary facility at the nearby Civilian Personnel Records Center, plastic

milk crates, eventually 30,000 of them, were used for open shelf drying, but a

better solution was on the horizon.

A

vacuum drying chamber was located at the McDonnell Douglas Aircraft plant in

St. Louis. The chamber was originally

constructed for space simulation as part of the Apollo moon program. Once archivists confirmed the technology

worked, two additional chambers at the Sandusky, Ohio NASA facility were located

and used as well. Wet records were

placed in the plastic milk crates, which were stacked nine high on wood

pallets, and the records loaded into the chamber, which was sealed. Air was evacuated from the chamber and the

temperature lowered to freezing. Hot dry

air was then introduced until the wetted materials reach 50 degrees F. Depending upon how wet the material was,

multiple cycles could be needed to dry the records. With a single chamber capable of holding

2,000 milk crates, nearly eight tons or 2000 gallons of water could be removed

during a run.

The

charred and burned materials recoverable from the sixth floor created another

challenge. Luckily, this material was

not disposed of following the fire, but stored as “B” files, as improvements in

technology have made the information from some of these materials usable

again. Today a team of thirty uses the

latest restoration techniques to recover information from these documents. Working

in latex gloves, this group represents an archival CSI for documents; cleaning

mold and debris and utilizing digital technology, scanners, and specialized

software, some information from burned sections can be revealed and

recovered.

This

information remains important. Requests

are received from veteran’s families for information needed to obtain various

programmatic government benefits along with on-going work by genealogists and

historians. The meticulous work the

recovery team does, like archaeologists unearthing an ancient village filled

with information, is critical in helping these servicemen.

Sprinkler

protection became an important component for all such government facilities

following this fire; a lesson learned like many others, through disaster. While we will likely never know how many

records were lost in the fire, the cause of which remains undetermined, that

recovery and restoration continues forty years later is nothing short of

miraculous.

Published on August 03, 2013 08:48

Fire Archaeology: Still Salvaging After All These Years

The

stories of most major fires concentrate on the immediate impact; the deaths and

injuries which resulted. Just over 40

years ago, a fire occurred which caused no deaths or serious injuries, the

impact from which is still being felt.

Just after midnight on July 12, 1973, fire broke out on the sixth floor

of the National Personnel Records Center in Overland, Missouri.

Construction

work on this building to hold military service records was completed in

1956. When the original studies were

conducted during the design phase, conflicting advice was received from

archivists and personnel at other government records retention facilities. Some strongly recommended the inclusion of

automatic sprinklers and others argued against.

Not surprisingly, since we are talking about this fire forty years

later, the anti-sprinkler forces won. Storage

of paper records in folders and boxes packed on metal shelves and file cabinets

filled the building—a massive fire load.

The

fire response exceeded 6 alarms. The

interior attack was abandoned at 3:15 AM that morning due to deteriorating

conditions, but the exterior attack continued for days. On the 14th, firefighters

re-entered the building to begin final extinguishment and overhaul on the sixth

floor; a task complicated by partial structural collapse of the roof. By the 16th of July, a single

company remained on scene.

Following

fire extinguishment began a salvage operation which continues even today. Computer tapes and microfilm records were

among the early transfers to an off-site facility. All six floors of the building experienced

substantial water damage, and the recovery of water soaked records was a

massive operation. Wet records were

re-boxed and the escalator railings used as a slide to move them to the ground

floor for transport. Setting up a

temporary facility at the nearby Civilian Personnel Records Center, plastic

milk crates, eventually 30,000 of them, were used for open shelf drying, but a

better solution was on the horizon.

A

vacuum drying chamber was located at the McDonnell Douglas Aircraft plant in

St. Louis. The chamber was originally

constructed for space simulation as part of the Apollo moon program. Once archivists confirmed the technology

worked, two additional chambers at the Sandusky, Ohio NASA facility were located

and used as well. Wet records were

placed in the plastic milk crates, which were stacked nine high on wood

pallets, and the records loaded into the chamber, which was sealed. Air was evacuated from the chamber and the

temperature lowered to freezing. Hot dry

air was then introduced until the wetted materials reach 50 degrees F. Depending upon how wet the material was,

multiple cycles could be needed to dry the records. With a single chamber capable of holding

2,000 milk crates, nearly eight tons or 2000 gallons of water could be removed

during a run.

The

charred and burned materials recoverable from the sixth floor created another

challenge. Luckily, this material was

not disposed of following the fire, but stored as “B” files, as improvements in

technology have made the information from some of these materials usable

again. Today a team of thirty uses the

latest restoration techniques to recover information from these documents. Working

in latex gloves, this group represents an archival CSI for documents; cleaning

mold and debris and utilizing digital technology, scanners, and specialized

software, some information from burned sections can be revealed and

recovered.

This

information remains important. Requests

are received from veteran’s families for information needed to obtain various

programmatic government benefits along with on-going work by genealogists and

historians. The meticulous work the

recovery team does, like archaeologists unearthing an ancient village filled

with information, is critical in helping these servicemen.

Sprinkler

protection became an important component for all such government facilities

following this fire; a lesson learned like many others, through disaster. While we will likely never know how many

records were lost in the fire, the cause of which remains undetermined, that

recovery and restoration continues forty years later is nothing short of

miraculous.

stories of most major fires concentrate on the immediate impact; the deaths and

injuries which resulted. Just over 40

years ago, a fire occurred which caused no deaths or serious injuries, the

impact from which is still being felt.

Just after midnight on July 12, 1973, fire broke out on the sixth floor

of the National Personnel Records Center in Overland, Missouri.

Construction

work on this building to hold military service records was completed in

1956. When the original studies were

conducted during the design phase, conflicting advice was received from

archivists and personnel at other government records retention facilities. Some strongly recommended the inclusion of

automatic sprinklers and others argued against.

Not surprisingly, since we are talking about this fire forty years

later, the anti-sprinkler forces won. Storage

of paper records in folders and boxes packed on metal shelves and file cabinets

filled the building—a massive fire load.

The

fire response exceeded 6 alarms. The

interior attack was abandoned at 3:15 AM that morning due to deteriorating

conditions, but the exterior attack continued for days. On the 14th, firefighters

re-entered the building to begin final extinguishment and overhaul on the sixth

floor; a task complicated by partial structural collapse of the roof. By the 16th of July, a single

company remained on scene.

Following

fire extinguishment began a salvage operation which continues even today. Computer tapes and microfilm records were

among the early transfers to an off-site facility. All six floors of the building experienced

substantial water damage, and the recovery of water soaked records was a

massive operation. Wet records were

re-boxed and the escalator railings used as a slide to move them to the ground

floor for transport. Setting up a

temporary facility at the nearby Civilian Personnel Records Center, plastic

milk crates, eventually 30,000 of them, were used for open shelf drying, but a

better solution was on the horizon.

A

vacuum drying chamber was located at the McDonnell Douglas Aircraft plant in

St. Louis. The chamber was originally

constructed for space simulation as part of the Apollo moon program. Once archivists confirmed the technology

worked, two additional chambers at the Sandusky, Ohio NASA facility were located

and used as well. Wet records were

placed in the plastic milk crates, which were stacked nine high on wood

pallets, and the records loaded into the chamber, which was sealed. Air was evacuated from the chamber and the

temperature lowered to freezing. Hot dry

air was then introduced until the wetted materials reach 50 degrees F. Depending upon how wet the material was,

multiple cycles could be needed to dry the records. With a single chamber capable of holding

2,000 milk crates, nearly eight tons or 2000 gallons of water could be removed

during a run.

The

charred and burned materials recoverable from the sixth floor created another

challenge. Luckily, this material was

not disposed of following the fire, but stored as “B” files, as improvements in

technology have made the information from some of these materials usable

again. Today a team of thirty uses the

latest restoration techniques to recover information from these documents. Working

in latex gloves, this group represents an archival CSI for documents; cleaning

mold and debris and utilizing digital technology, scanners, and specialized

software, some information from burned sections can be revealed and

recovered.

This

information remains important. Requests

are received from veteran’s families for information needed to obtain various

programmatic government benefits along with on-going work by genealogists and

historians. The meticulous work the

recovery team does, like archaeologists unearthing an ancient village filled

with information, is critical in helping these servicemen.

Sprinkler

protection became an important component for all such government facilities

following this fire; a lesson learned like many others, through disaster. While we will likely never know how many

records were lost in the fire, the cause of which remains undetermined, that

recovery and restoration continues forty years later is nothing short of

miraculous.

Published on August 03, 2013 08:48

July 27, 2013

Farm Spayer to Fire Truck

If you stay around long enough,

you’ll see that many things in the fire service are cyclical. In the late 1930s, an orchard owner noticed

his neighbor’s house burning, and dragged his sprayer, manufactured by a guy

named Bean, over to fight and ultimately extinguish the fire. From this developed the high pressure fog

system for fire apparatus. It was not unlike many pieces of equipment

which had their start in other applications—think high lift jacks and positive

pressure ventilation fans—so did high pressure, adapted from agricultural

use. In the 1940s and 1950s, the use of

high pressure fog was a common tactic and its face was the ubiquitous John Bean, at least one of which was

seemingly owned by every rural or suburban department.

The pumps operated at 650-800 psi

at low flow through gun type nozzles.

Useful on indirect attack situations, there were weaknesses in other

applications. Overtaken by volume pumps

and larger lines, they slowly faded from use on structure fires. The parent company, FMC Fire Apparatus, ultimately

ceased operations in 1990 following a failed expansion into ladder trucks.

Today, the technology is rearing its

head again in the form of ultra-high pressure.

Pumps for low flow 18-22 gpm

handlines delivering water at 1100-1400 psi are now being manufactured by HMA

Fire. As with many “new” technologies,

it is being suggested for a variety of applications from ARFF to woodland, and

yes, even structural fires. Where it

will go is unclear, but the fire service trip around the circle is virtually

complete.

you’ll see that many things in the fire service are cyclical. In the late 1930s, an orchard owner noticed

his neighbor’s house burning, and dragged his sprayer, manufactured by a guy

named Bean, over to fight and ultimately extinguish the fire. From this developed the high pressure fog

system for fire apparatus. It was not unlike many pieces of equipment

which had their start in other applications—think high lift jacks and positive

pressure ventilation fans—so did high pressure, adapted from agricultural

use. In the 1940s and 1950s, the use of

high pressure fog was a common tactic and its face was the ubiquitous John Bean, at least one of which was

seemingly owned by every rural or suburban department.

The pumps operated at 650-800 psi

at low flow through gun type nozzles.

Useful on indirect attack situations, there were weaknesses in other

applications. Overtaken by volume pumps

and larger lines, they slowly faded from use on structure fires. The parent company, FMC Fire Apparatus, ultimately

ceased operations in 1990 following a failed expansion into ladder trucks.

Today, the technology is rearing its

head again in the form of ultra-high pressure.

Pumps for low flow 18-22 gpm

handlines delivering water at 1100-1400 psi are now being manufactured by HMA

Fire. As with many “new” technologies,

it is being suggested for a variety of applications from ARFF to woodland, and

yes, even structural fires. Where it

will go is unclear, but the fire service trip around the circle is virtually

complete.

Published on July 27, 2013 06:43

July 20, 2013

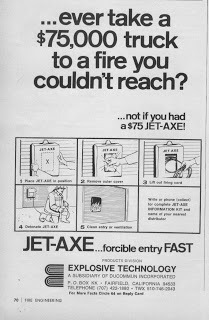

James Bond—Nope, More Like Maxwell Smart: The Jet Axe

The

side compartment of the vehicle was opened and the rectangular package removed

and carried to the ladder located in front of the smoking building. The action hero briskly climbed to the roof

and brought his burden to near the ridge line, carefully laying it with the

long axis perpendicular to the peak.

He

punched a hole in the cover, pulling a hidden control box connected to the

package by a wire harness from the interior.

Retreating to the safety of the ladder, he climbed below the eave to

shield himself, tempted to yell out “fire in the hole.” Pushing the button on the control in his

hand was thrilling. The noise from the

explosion caught the attention of all those nearby. Smoke poured from the opening in the roof, a

perfectly cut rectangle in the shape of the package, not from the explosion, but

from the fire below.

Ventilation

without a saw; what a concept. This

isn’t Bond, Schwarzenegger, Stallone, or Bruce Willis, nor is it a USFA

development project for 2017. This is

technology from the middle of the last century; the Jet Axe.

The

Jet-Axe wasn’t just for ventilation; it could be used for forcible entry as

well. Developed using military style

explosives, and designed to focus the blast in a narrow area, it came into use primarily

in the late 1960s, and out shortly thereafter.

The manufacturer apparently did not account for the explosive contents

becoming unstable over time and bouncing about in ladder truck compartments.

Legend

has it that the problem first reared its head in San Francisco when an

unsuspecting truck company had a new hole where a compartment door previously

resided--a Jet-Axe “operated” while the ladder truck was underway. Word spread quickly, and most were removed

from service promptly.

For

those of an inventive nature, research shows that the trade-mark on the name

expired in 2001 (making it available again) and was last owned by Explosive

Technology, Inc. in Fairfield, California.

Lots of things in the fire service are cyclical in nature; maybe this

will be another...

side compartment of the vehicle was opened and the rectangular package removed

and carried to the ladder located in front of the smoking building. The action hero briskly climbed to the roof

and brought his burden to near the ridge line, carefully laying it with the

long axis perpendicular to the peak.

He

punched a hole in the cover, pulling a hidden control box connected to the

package by a wire harness from the interior.

Retreating to the safety of the ladder, he climbed below the eave to

shield himself, tempted to yell out “fire in the hole.” Pushing the button on the control in his

hand was thrilling. The noise from the

explosion caught the attention of all those nearby. Smoke poured from the opening in the roof, a

perfectly cut rectangle in the shape of the package, not from the explosion, but

from the fire below.

Ventilation

without a saw; what a concept. This

isn’t Bond, Schwarzenegger, Stallone, or Bruce Willis, nor is it a USFA

development project for 2017. This is

technology from the middle of the last century; the Jet Axe.

The

Jet-Axe wasn’t just for ventilation; it could be used for forcible entry as

well. Developed using military style

explosives, and designed to focus the blast in a narrow area, it came into use primarily

in the late 1960s, and out shortly thereafter.

The manufacturer apparently did not account for the explosive contents

becoming unstable over time and bouncing about in ladder truck compartments.

Legend

has it that the problem first reared its head in San Francisco when an

unsuspecting truck company had a new hole where a compartment door previously

resided--a Jet-Axe “operated” while the ladder truck was underway. Word spread quickly, and most were removed

from service promptly.

For

those of an inventive nature, research shows that the trade-mark on the name

expired in 2001 (making it available again) and was last owned by Explosive

Technology, Inc. in Fairfield, California.

Lots of things in the fire service are cyclical in nature; maybe this

will be another...

Published on July 20, 2013 09:07

July 13, 2013

The Firefighter Trampoline

Jumping from a burning building has long been, and remains,

the last resort of a desperate victim, usually with less than optimum

results. But on November 10, 1904, two girls jumped

from an overcrowded fire escape platform, and this time things were

different. They were caught by New York

City firefighters using an unusual circular fabric device, a safety net. Now more recognized in comedic videos and

seen in museums, the Browder Safety Net was at one time a common piece of

equipment for ladder companies.

Developed by a Civil War veteran by the name of Thomas F. Browder in

1887; he continued to evolve and improve the design, adding additional patents

in 1900.

There were other successes, including one in 1901 in New

York City in which twenty people reportedly leaped to safety. Failures, though, were common as well. In Newark in 1910, four women jumped

simultaneously from an upper floor of a factory and tore through the net. Although two deployed nets saved a few, a

similar situation occurred at the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire and

many more jumpers were missed. Additional stories on other fires abound of

individual victims who jumped, but missed the net or hit the edge, sometimes

injuring firefighters.

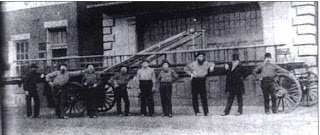

Ladder trucks carried the net folded and typically mounted

vertically on the side of the apparatus.

It could be deployed in seconds, but required at least ten or more firefighters

holding it at shoulder height, in the right place and time. With the fabric center and springs connecting

it to the circular frame, it was a portable man held version of the circus

trampoline, but with less bounce.

The ideal way in which to jump was with the legs straight

out in a seated-like position, and arms crossed in front of the torso with the

objective being to land on the small of the back or buttocks. While a firefighter could easily be taught

this during a routine training session, a victim at a fourth floor window with

smoke pouring from around them or flames nipping at their heels would not be a

receptive student. The firefighters on

the ground would catch them, or try to, in any orientation in which they

jumped.

As time passed and the length of aerial ladders increased,

the need for the Browder net decreased.

Concerns over its safety and effectiveness grew and in the 1950s

departments began to phase out their use.

These nets are now little more than a curiosity, displayed in museums,

fire stations, and at least one firefighter’s home bar. If keeping a fire scene from being a “circus”

is a good thing, no longer bringing our own trampoline probably helps.

the last resort of a desperate victim, usually with less than optimum

results. But on November 10, 1904, two girls jumped

from an overcrowded fire escape platform, and this time things were

different. They were caught by New York

City firefighters using an unusual circular fabric device, a safety net. Now more recognized in comedic videos and

seen in museums, the Browder Safety Net was at one time a common piece of

equipment for ladder companies.

Developed by a Civil War veteran by the name of Thomas F. Browder in

1887; he continued to evolve and improve the design, adding additional patents

in 1900.

There were other successes, including one in 1901 in New

York City in which twenty people reportedly leaped to safety. Failures, though, were common as well. In Newark in 1910, four women jumped

simultaneously from an upper floor of a factory and tore through the net. Although two deployed nets saved a few, a

similar situation occurred at the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire and

many more jumpers were missed. Additional stories on other fires abound of

individual victims who jumped, but missed the net or hit the edge, sometimes

injuring firefighters.

Ladder trucks carried the net folded and typically mounted

vertically on the side of the apparatus.

It could be deployed in seconds, but required at least ten or more firefighters

holding it at shoulder height, in the right place and time. With the fabric center and springs connecting

it to the circular frame, it was a portable man held version of the circus

trampoline, but with less bounce.

The ideal way in which to jump was with the legs straight

out in a seated-like position, and arms crossed in front of the torso with the

objective being to land on the small of the back or buttocks. While a firefighter could easily be taught

this during a routine training session, a victim at a fourth floor window with

smoke pouring from around them or flames nipping at their heels would not be a

receptive student. The firefighters on

the ground would catch them, or try to, in any orientation in which they

jumped.

As time passed and the length of aerial ladders increased,

the need for the Browder net decreased.

Concerns over its safety and effectiveness grew and in the 1950s

departments began to phase out their use.

These nets are now little more than a curiosity, displayed in museums,

fire stations, and at least one firefighter’s home bar. If keeping a fire scene from being a “circus”

is a good thing, no longer bringing our own trampoline probably helps.

Published on July 13, 2013 08:04

July 5, 2013

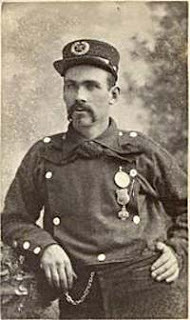

From Triumph to Tragedy: The Legendary Phelim O’Toole

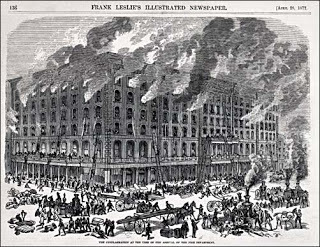

An otherwise ordinary evening was followed by tragedy and

heroism in the early morning hours of April 11, 1877. The elegant Italianate style six story Southern

Hotel, almost a football field in length faced Walnut St. in downtown St.

Louis. At about twenty minutes after one

in the morning, a fire was discovered in the basement. Notification of the fire department was

delayed by upwards of ten minutes due to a lost key to the fire alarm box,

allowing the fire to spread to the upper floors via vertical shafts.

The first alarm brought six engine and two truck companies

for the fire which ultimately would go to three alarms and requirel the

response of every piece of apparatus in the city. The first arriving ladder company, a “Skinner

Escape Truck,” was led by Foreman Phelim O’Toole. O’Toole was an Irish immigrant who was hired

by the St. Louis Fire Department at the age of 18, about ten years before that

night.

Upon arrival, O’Toole noted fire on the upper floors and

almost a dozen occupants yelling from windows.

Positioning the truck was difficult due to obstructions, but when in the

best position possible, they extended the ladder and O’Toole began to

climb. Fully extended, Phelim found

himself five feet short of the 6th floor window sill.

Accounts vary some, but by most, O’Toole had the occupants

tie bed sheets together as a rope, securing their end to a bedframe, and then

lower the other end from the window. He

swung out on a rope from the ladder tip to the dangling bed sheets, and climbed

to the upper window sill, and began to lower the victims to firefighters on the

waiting ladder. Moving from window to

window, he is credited with saving over a dozen people. Conditions continued to deteriorate, but the

last reachable victim was removed just before the building collapsed, taking

twenty one remaining occupants with it.

It was following the Southern Hotel fire that the Pompier

Corps of the St. Louis Fire Department was developed. Pompier Corps

O’Toole received a $500 award from the city, which he

donated to assist orphans. This was a sizable sum when compared to his monthly

salary of $75.00.

The Southern Hotel was not O’Toole’s last experience at the

end of a rope. A serious fire erupted in

the dome of the County Courthouse.

Phelim climbed the dome with an axe, rope, and hoseline. After chopping through the roof, he tied off

the rope and entered through the hole.

Dangling from the rope, he attacked the fire with the handline.

Shortly after, on July 6, 1880, O’Toole died in the line of

duty. It was not another dramatic scene,

but a “routine” cellar fire in a vacant house.

He entered the building with a hand held extinguisher, and when he began

to operate it, the casing exploded, pieces tearing into his chest, fatally

injuring him at 32 years of age.

His funeral service was as big as his reputation with an

estimated 20,000 people attending. Gone

but not forgotten, the St. Louis Fire Department continues to honor his memory,

christening the marine unit fire boat the “Phelim O’Toole” in 1994.

Published on July 05, 2013 03:43

June 28, 2013

Not Sexy but Necessary: Overhaul

There are few jobs on the fire ground less sexy than

overhaul. That said, it is right up

there with laddering the building, ventilation, and the like in terms of

importance. Long before I was old enough

to wear bunker fear for more than cute pictures, I heard my father, “generation

one,” repeat one of his main firefighting philosophical tenets on the subject

multiple times: “There is no such thing

as a rekindle.”

Overhaul can be hard, dirty, nasty work. It’s a time when many tired firefighters get

injured. On heavily damaged structures

it can be highly challenging. One bad

habit some departments get into is substituting the use of Class A foam for

good overhaul practices. “Just soak the

hell out of it. The foam will take care

of it,” is something I’ve heard more than once.

Sorry, but there is no substitute for good overhaul—period. This is not

a “how to” piece, just a suggestion to refocus on an important ingredient in

the recipe.

It can present a great learning opportunity for

inexperienced firefighters. They can

learn about fire behavior, travel, construction types, cause and origin, and

myriad other topics. Nothing says that

the officer supervising them has to remain silent. He or she can talk about all these things

while the crew works, using things they find as examples. We have great tools today, unavailable years

ago, such as thermal imaging cameras, but even this can be a crutch for proper

overhaul if you let it.

The building is in the basement and not safe or

accessible? Don’t just go home and wait

for the neighbors to call in the “rekindle.”

Leave a single company or make arrangements to send one out at a set

time to take care of the anticipated flare-ups.

You may need to do either or both for days, depending upon the

building.

Whatever the fire situation, don’t just call it out and go

home because everybody is tired. There’s

no such thing as a rekindle—only the fire that didn’t get put out the first

time.

overhaul. That said, it is right up

there with laddering the building, ventilation, and the like in terms of

importance. Long before I was old enough

to wear bunker fear for more than cute pictures, I heard my father, “generation

one,” repeat one of his main firefighting philosophical tenets on the subject

multiple times: “There is no such thing

as a rekindle.”

Overhaul can be hard, dirty, nasty work. It’s a time when many tired firefighters get

injured. On heavily damaged structures

it can be highly challenging. One bad

habit some departments get into is substituting the use of Class A foam for

good overhaul practices. “Just soak the

hell out of it. The foam will take care

of it,” is something I’ve heard more than once.

Sorry, but there is no substitute for good overhaul—period. This is not

a “how to” piece, just a suggestion to refocus on an important ingredient in

the recipe.

It can present a great learning opportunity for

inexperienced firefighters. They can

learn about fire behavior, travel, construction types, cause and origin, and

myriad other topics. Nothing says that

the officer supervising them has to remain silent. He or she can talk about all these things

while the crew works, using things they find as examples. We have great tools today, unavailable years

ago, such as thermal imaging cameras, but even this can be a crutch for proper

overhaul if you let it.

The building is in the basement and not safe or

accessible? Don’t just go home and wait

for the neighbors to call in the “rekindle.”

Leave a single company or make arrangements to send one out at a set

time to take care of the anticipated flare-ups.

You may need to do either or both for days, depending upon the

building.

Whatever the fire situation, don’t just call it out and go

home because everybody is tired. There’s

no such thing as a rekindle—only the fire that didn’t get put out the first

time.

Published on June 28, 2013 14:44

Gary R. Ryman's Blog

- Gary R. Ryman's profile

- 3 followers

Gary R. Ryman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.