Gary R. Ryman's Blog, page 12

October 26, 2012

Oh Where Oh Where Should My Red Light Be...

Warning lights in the 1960s weren’t the high efficiency

LED’s or strobes we see today. A single

bulb “Vitalite” was the norm. Back then,

West Corners had a whopping two traffic lights, both of which were relatively

new. Heavy traffic for emergency

responders was not a major problem.

Mom was not a fan of lights on the roof of cars. She felt they detracted from the looks. Further, she didn’t even like them on the

front dash, arguing they obstructed her vision.

None of this was much of an issue when Dad was a

firefighter, lieutenant, or captain. We

lived less than a mile from the station; one stop sign and two turns away. When he made Assistant Chief and had to start

responding to the scene, things changed.

A mobile radio—with tubes—was installed in the car. A miniature manual siren was bolted under the

hood. Neither of these was a problem; it

was the red light that was in dispute.

Locating it on the roof was out of the question and her objections

regarding the front dash were continued.

The light ended up on the rear deck in the back window of the old

Dodge.

This location was one step above useless. When parked at a scene, it could be useful,

but did little to expedite actually getting there.

All this changed one fortuitous day when Mom and I happened

to be in the car with Dad when a fire call was received. Dad called out as responding and activated

the light on the rear deck and the dinky siren, and attempted to weave his way

through what passed as traffic in our little town. In the front seat, Mom was astounded at the

difficulty he experienced.

“Why won’t these people pull over?” She asked, incredulous over

this lack of cooperation, her hands braced o the dash board against the bobbing

and weaving of the car.

“Because nobody can see the damn light,” Dad said. Mom knew better than to continue the

conversation while we were enroute to the call.

Meanwhile, I was having a blast in the back seat; seeing the flashes of

red bounce in and out of the car and looking for smoke in the sky in front of

us.

Mom and I watched from the car while the incident, nothing

serious if memory serves, was handled.

When the fire apparatus was repacked and returning to the station, Dad

got back in the car. Mom had apparently

been giving some thought to the ride we took to the scene and her previous

position on the location of the red light in the car. Before Dad had barely settled in to start the

ignition, she revealed her decision.

“Rich, put the damn light wherever you want it.”

Dad didn’t say anything, but before the day was out, the

center of the roof was graced with the old single bulb red light.

LED’s or strobes we see today. A single

bulb “Vitalite” was the norm. Back then,

West Corners had a whopping two traffic lights, both of which were relatively

new. Heavy traffic for emergency

responders was not a major problem.

Mom was not a fan of lights on the roof of cars. She felt they detracted from the looks. Further, she didn’t even like them on the

front dash, arguing they obstructed her vision.

None of this was much of an issue when Dad was a

firefighter, lieutenant, or captain. We

lived less than a mile from the station; one stop sign and two turns away. When he made Assistant Chief and had to start

responding to the scene, things changed.

A mobile radio—with tubes—was installed in the car. A miniature manual siren was bolted under the

hood. Neither of these was a problem; it

was the red light that was in dispute.

Locating it on the roof was out of the question and her objections

regarding the front dash were continued.

The light ended up on the rear deck in the back window of the old

Dodge.

This location was one step above useless. When parked at a scene, it could be useful,

but did little to expedite actually getting there.

All this changed one fortuitous day when Mom and I happened

to be in the car with Dad when a fire call was received. Dad called out as responding and activated

the light on the rear deck and the dinky siren, and attempted to weave his way

through what passed as traffic in our little town. In the front seat, Mom was astounded at the

difficulty he experienced.

“Why won’t these people pull over?” She asked, incredulous over

this lack of cooperation, her hands braced o the dash board against the bobbing

and weaving of the car.

“Because nobody can see the damn light,” Dad said. Mom knew better than to continue the

conversation while we were enroute to the call.

Meanwhile, I was having a blast in the back seat; seeing the flashes of

red bounce in and out of the car and looking for smoke in the sky in front of

us.

Mom and I watched from the car while the incident, nothing

serious if memory serves, was handled.

When the fire apparatus was repacked and returning to the station, Dad

got back in the car. Mom had apparently

been giving some thought to the ride we took to the scene and her previous

position on the location of the red light in the car. Before Dad had barely settled in to start the

ignition, she revealed her decision.

“Rich, put the damn light wherever you want it.”

Dad didn’t say anything, but before the day was out, the

center of the roof was graced with the old single bulb red light.

Published on October 26, 2012 11:47

October 13, 2012

Inside

The

engine company pulls up in front of the single story house, the siren winding

down. Grey black smoke oozes from

previously unknown cracks and windows, doors, and the building eaves. The firefighter in the rear dismounts and

reaches for the nozzle and hose stacked in the horizontal bed or cross lay and

pulls it onto his shoulder. The officer,

axe and halligan bar, the “irons” in his hand, pulls the hose from the second

stack as the firefighter advances toward the front door. The driver comes around the engine and

relieves the officer at this so he can follow the firefighter.

At the front door, the officer

wrenches open the screen, disabling it so it won’t close on them while the

firefighter flakes out the remaining hose from his shoulder to ensure smooth

entry to the building without kinks or catches.

Dropping the nozzle, he takes the axe from the officer who jams the pry

end of the halligan into the wood frame by the lock in the door. With one good whack, the door pops open and

smoke pours from around it.

Pulling the door shut again, the

officer and firefighter drop to their knees and drop their helmets to the

ground, putting on breathing apparatus face pieces and protective hoods in a

well-practiced motion. Hood, helmet, and

gloves in place, the firefighter picks up the nozzle, the hose now hard with

water, and pushes the fractured front door open again. With a well-trained crew, the process takes

place without the exchange of a word; poetry in motion.

The firefighter and officer enter

the blackness of the house, their eyes widening to the physical limits,

attempting to see the fire. Their senses

go into overdrive, adrenaline having a romp through their bodies. Both listen for the crackling of flames and

feeling heat through their protective clothing, trying to discern the direction

from which it emanates. Windows shatter

as fellow arriving firefighters begin to ventilate the building, hoping to

allow heat and smoke to escape; making conditions better for the attack

crew—and any victims who might remain.

A few feet further in, the nozzleman

spies a glow in front of him through the viscous smoke; just a fleeting glance,

but it gives him a direction to head.

“It’s straight ahead,” he yells, his

voice muffled by the face piece along with the hissing of the inhalation and

exhalation from his and the officer’s mask.

Their conversations are now short, but more frequent, punctuated by

expletives. They drag and pull the hose

another yard or so to the kitchen doorway where the fire is now more visible,

starting to roll over their heads into the living room. This is not the made for television fire with

the perfect visibility of gas jets (sorry Chicago Fire). Here the flames remain muted by the smoke,

the heat pushing the attack team into the floor.

The firefighter opens the nozzle,

directing the fist thick straight stream of water at the ceiling, whipping it

in circles. The water makes a staccato

thumping bass drum against the plaster, but without rhythm. . The firefighter and officer push into the

room and the angle of the hose stream drops as the nozzleman hits flames at

cabinet level throughout the room.

Visibility, if anything, is worse as the water converts the fire to

steam and the heat and smoke and ceiling level drop, the plume inverted by the

water application. Other firefighters

spread into the house, searching for victims or the spread of the fire beyond

the kitchen.

The bulk of the fire now out in the

kitchen, another firefighter with a pike pole, a long stick with a hook at the

end, pushes past the nozzleman and thrusts the pike into the ceiling. Pulling down the plaster, the space above,

and any remaining fire, is visible for the nozzleman to hit with his

stream. The smoke and heat begin to

lift, exiting through the broken kitchen windows, leaving a smother wet jungle

in the room. A few more minutes of work

and it becomes clear the bulk of the fire is out.

The firefighter and officer are

relieved by others and head outside for a break. Kneeling again on the front lawn, they remove

their helmets and face pieces and open their bunker coats. In the cool fall air, steam rises from their

uncovered heads and bodies, condensing from the sweat.

They smile and converse about this

easy fire as the adrenaline surging through their systems begins to

recede. A satisfaction is left having

completed what they regularly trained for, going against the beast or the “Red

Devil” as it is sometimes described.

It’s an untenable environment after just a few minutes without the right

equipment and one that few want to visit much less work in. That increases the satisfaction; doing

something only a small percentage of people can do, going “inside.”

Published on October 13, 2012 03:39

October 6, 2012

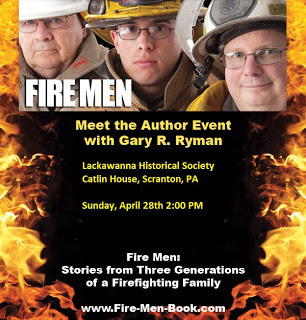

Looking Forward to an Upcoming Event

Published on October 06, 2012 05:19

October 5, 2012

Excerpt

An excerpt from Fire Men recently was posted and is available here. Fire Men excerpt Take a look.

You can also check out my interview about the book here. Interview

You can also check out my interview about the book here. Interview

Published on October 05, 2012 04:21

September 29, 2012

The Demise of "Hearse" Ambulances and Other Good Things

Anyone who ever watched Emergency

when originally on network television or later in syndication understands how

far EMS, among other things, has come in the fire service. With few exceptions, medical responses have

long ago taken the lead over fire calls.

Some contend the name fire department is no longer accurate. While I understand these arguments, I’m not

prepared to go that far—yet. However, if you’re a firefighter today,

particularly a young one, you better learn to “like” EMS, or consider another

profession, because it isn’t going away.

The development of ALS while the most prominent and

recognized improvement is far from the only change. Ambulance services run by funeral directors

with a red light tossed onto the roof of a hearse have, thankfully, gone the

way of the horses. Overall

availability has improved as well.

How much? A lot. When I was six or seven years old, some

buddies and I were playing in the woods, jumping in piles of leaves and

generally doing the things young boys did back then when no one had to be

worried about us being kidnapped if we went ten minutes from the house. One boy jumped into a pile over a bank and

hit something hidden beneath the leaves, breaking his femur. His screams of pain frightened the living

hell out of the rest of us. There was no

thought of moving him, not because we knew not to, but because of fear. Practically as one, we all started running

for our respective homes for one thing; to get our mothers—it was the 60s, they

were home.

The group of mothers followed us back, and mine, being a

nurse, promptly recognized the fracture for what it was. An ambulance was called, but it wasn’t quite

as simple as today. The first due fire

department where Dad was a member had no ambulance or any medical capabilities

at all. No help there. The neighboring department had an ambulance,

but they only responded outside of their first due area on nights and

weekends. Monday through Friday, eight

to four, they didn’t leave the district.

In the next village over, the police department ran the ambulance. They didn’t leave their town at all,

regardless of time or day. The only unit

available was operated by the county Sheriff’s department. The road patrol deputy had to respond to get

the ambulance from wherever he happened to be, and then across half the county

to where we were waiting. This wasn’t a rural area either; the suburban

town had a population in the tens of thousands.

Almost an hour later, it arrived to transport the boy. Luckily the break hadn’t hit the artery or

he’d have been dead long before the unit arrived. After an extended convalescence; most of a

school year, he recovered.

Good? No, but normal

back then, so yes, things other than just ALS have changed a lot. As much as almost no one wants to be on the

ambulance every shift, I think everyone

would agree things are better now.

when originally on network television or later in syndication understands how

far EMS, among other things, has come in the fire service. With few exceptions, medical responses have

long ago taken the lead over fire calls.

Some contend the name fire department is no longer accurate. While I understand these arguments, I’m not

prepared to go that far—yet. However, if you’re a firefighter today,

particularly a young one, you better learn to “like” EMS, or consider another

profession, because it isn’t going away.

The development of ALS while the most prominent and

recognized improvement is far from the only change. Ambulance services run by funeral directors

with a red light tossed onto the roof of a hearse have, thankfully, gone the

way of the horses. Overall

availability has improved as well.

How much? A lot. When I was six or seven years old, some

buddies and I were playing in the woods, jumping in piles of leaves and

generally doing the things young boys did back then when no one had to be

worried about us being kidnapped if we went ten minutes from the house. One boy jumped into a pile over a bank and

hit something hidden beneath the leaves, breaking his femur. His screams of pain frightened the living

hell out of the rest of us. There was no

thought of moving him, not because we knew not to, but because of fear. Practically as one, we all started running

for our respective homes for one thing; to get our mothers—it was the 60s, they

were home.

The group of mothers followed us back, and mine, being a

nurse, promptly recognized the fracture for what it was. An ambulance was called, but it wasn’t quite

as simple as today. The first due fire

department where Dad was a member had no ambulance or any medical capabilities

at all. No help there. The neighboring department had an ambulance,

but they only responded outside of their first due area on nights and

weekends. Monday through Friday, eight

to four, they didn’t leave the district.

In the next village over, the police department ran the ambulance. They didn’t leave their town at all,

regardless of time or day. The only unit

available was operated by the county Sheriff’s department. The road patrol deputy had to respond to get

the ambulance from wherever he happened to be, and then across half the county

to where we were waiting. This wasn’t a rural area either; the suburban

town had a population in the tens of thousands.

Almost an hour later, it arrived to transport the boy. Luckily the break hadn’t hit the artery or

he’d have been dead long before the unit arrived. After an extended convalescence; most of a

school year, he recovered.

Good? No, but normal

back then, so yes, things other than just ALS have changed a lot. As much as almost no one wants to be on the

ambulance every shift, I think everyone

would agree things are better now.

Published on September 29, 2012 10:43

September 19, 2012

A Challenging Mantra

Former quarterback Jon Kitna isn’t living the life of

leisure in his retirement. He’s teaching

high school algebra and coaching football, and most importantly teaching life

lessons. The acronym he uses for the

values he tries to impart is REAL.

·

Reject

passivity

·

Empathize

with others

·

Accept

responsibility

·

Lead

courageously

The parallels are clear.

If underprivileged high school students can absorb this cultural

challenge and change, hopefully so can our young firefighters—if we teach

it.

Published on September 19, 2012 15:57

September 16, 2012

Pizza Pie and Electrocution: The Srange Things That Bring Back Memories

Leaving a great pizza place in Endicott (Consols—originally Duffs—the

same recipe for well over fifty years, but that’s another story) where Mike and

I had stuffed ourselves with Dad, we drove by the old IBM plant and I pointed

out a utility substation where I had one of my first serious calls as a

youngster.

It was a summer day shift, and we got hit for an injured

male. This wasn’t our usual first due

area but the ALS rig that normally covered it was on another call. That the dispatcher or caller left out a

little bit of information became rather evident when we pulled up on

scene.

There was a black male standing by the open gate of the

substation with his arms extended out from his side. Getting out of the front seat of the

ambulance, I noted my observation had been wrong. He wasn’t black—he was burned. We got him onto a sheet on the stretcher and

began carefully removing clothing where we could, and pouring sterile water

onto his burns, trying to keep him talking to us.

“They told us it was okay to dig there,” he kept

repeating. He and his partner had struck

a high voltage underground line and it had blown them from the hole they’d been

working in. His buddy appeared to be

less seriously injured than him but it’s sometimes hard to tell with electrical

shock. I called for another rig, and the

cop that arrived along with some first responders from the plant helped with

the second victim until a couple of our other members arrived on scene. With victim two stable, and the second rig on

the way, I decided to load and go with our patient. I was worried about his airway, cardiac

status; pretty much everything. The ALS

rig wasn’t available, and by the time we could get a medic to the scene POV, if

one was even around, we could be at the emergency room.

It was a wild and wooly ride as the far expanses of

Chevrolet horsepower were explored by the driver. We kept the victim talking all the way, the

best tool we had available to keep him out of deepening shock, using every drop

of distilled water in the cabinets on him as well. I was ready to see it pour out the rear door

when we backed into the ER ramp.

Both made a full recovery and then, a few months afterward,

filed a lawsuit against the utility that had let them dig there. Yours truly received his first, but certainly

not last, subpoena for deposition. I was

seventeen years old……

same recipe for well over fifty years, but that’s another story) where Mike and

I had stuffed ourselves with Dad, we drove by the old IBM plant and I pointed

out a utility substation where I had one of my first serious calls as a

youngster.

It was a summer day shift, and we got hit for an injured

male. This wasn’t our usual first due

area but the ALS rig that normally covered it was on another call. That the dispatcher or caller left out a

little bit of information became rather evident when we pulled up on

scene.

There was a black male standing by the open gate of the

substation with his arms extended out from his side. Getting out of the front seat of the

ambulance, I noted my observation had been wrong. He wasn’t black—he was burned. We got him onto a sheet on the stretcher and

began carefully removing clothing where we could, and pouring sterile water

onto his burns, trying to keep him talking to us.

“They told us it was okay to dig there,” he kept

repeating. He and his partner had struck

a high voltage underground line and it had blown them from the hole they’d been

working in. His buddy appeared to be

less seriously injured than him but it’s sometimes hard to tell with electrical

shock. I called for another rig, and the

cop that arrived along with some first responders from the plant helped with

the second victim until a couple of our other members arrived on scene. With victim two stable, and the second rig on

the way, I decided to load and go with our patient. I was worried about his airway, cardiac

status; pretty much everything. The ALS

rig wasn’t available, and by the time we could get a medic to the scene POV, if

one was even around, we could be at the emergency room.

It was a wild and wooly ride as the far expanses of

Chevrolet horsepower were explored by the driver. We kept the victim talking all the way, the

best tool we had available to keep him out of deepening shock, using every drop

of distilled water in the cabinets on him as well. I was ready to see it pour out the rear door

when we backed into the ER ramp.

Both made a full recovery and then, a few months afterward,

filed a lawsuit against the utility that had let them dig there. Yours truly received his first, but certainly

not last, subpoena for deposition. I was

seventeen years old……

Published on September 16, 2012 07:09

September 9, 2012

Some Stories From the "Old Man"

With the approaching of Dad’s 77th

birthday, some of the amusing stories about him from Fire Men come to mind.

His first actual fire call changed

him for life, but not in the dramatic way some might think. In the middle of the night, he woke up to the

siren wailing in the distance, down over the hill. He quickly got out of bed and dressed, racing

to the car. He sped toward the station,

less than a mile from the house, impressed with his reaction time and rapid

response to the emergency call.

When he got

to the station, he found he was a bit behind the curve. Numerous cars were already there, and all of

the fire apparatus—two pumpers and a squad truck—were already gone. Luckily, the call was only right down the

street; he could see the flashing lights at the nearby bank. Driving the short distance, he saw the

apparatus positioned around the building and ground ladders raised to the

roof. The fire was minor in nature, but

he quickly figured out he needed to pick up the pace if he ever hoped to make

it onto one of the fire trucks.

After that,

Dad became an efficiency expert’s dream.

Clothes were carefully laid out on the bureau each night before

bedtime. Keys, glasses, and cigarettes

were strategically positioned. The most

radical idea was yet to come: an automatic garage door opener. Those were unheard of in our neighborhood,

but Dad took it to the next level. Most

garage door openers, even today, have the button that activates them in the

garage next to the car. That wasn’t

enough for Dad. He put an additional

button in the closet in the bedroom which allowed him to hit the button while

getting dressed. The garage door would

already be open when he reached the garage, saving a good five seconds. A NASCAR pit crew would be impressed with his

speed out of the house. When I was about 11 years old, we moved to a new house

in a nearby neighborhood. One of the

first things wired in was the activation button for the garage door opener in

the closet of the master bedroom.

In the mid-1960s, a massive

technological advancement happened—Plectrons became available. Plectrons were tone-activated radio receivers

manufactured by the Plectron Corporation.

As far as firemen were concerned, they were the greatest thing since

sliced bread. Now they knew exactly

where and what type of fire they were going to.

The name Plectron for a tone-alerted receiver became the fire service

equivalent of Xerox for copiers.

The

original models weren’t even solid state, instead they used tubes. The warmth from the tubes made them

attractive to animals. My cat loved to

sleep on top of the Plectron because of the heat it emitted. The cat loved it

until the high pitched squealing tone alert went off at full volume. Then he would jump simultaneously up from the

radio and off of the top of the refrigerator upon which it sat. It was a sight to behold.

Because of

all this, as a young boy, the importance of speed out the door was ingrained in

me. When relatives visited, I knew to

advise them of safety measures I had developed out of necessity. If the tones went off, I would yell “quick,

Grandma, get in a chair! He’ll trample

you.” This came from the experience of

being treated as a track hurdle while playing with toys on the floor when a

fire call happened to come in.

To say that Dad could be a little

bit anal about equipment organization would be putting it mildly. I think it was the ex-Marine in him coming

out.

Our engines

varied in vintage from 1957 to 1975 back when he was a chief in the 1970s and

80s. What didn’t vary is where things

were located. You could open any

compartment on any of the four engines (three first line and one reserve) and

each piece of hardware, nozzle, appliance, wye, gate valve, etc., would be

found in exactly the same spot on every piece.

Hose was a

pet peeve of his. We had a spare load of

hose for each engine stored in doughnut rolls on hose racks in the rear of the

building. I would catch him regularly

rearranging the hose on the racks so the end butt of each roll was in perfect

alignment.

If he saw

you put a roll of hose on the racks and not line up the butt with the adjacent

ones, you would hear about it instantly.

This was not one of his saner practices.

Dad was

terrible with names. Guys in the

department upwards of five years were “hey you.” If he did know your name in less time, it was

not necessarily a good thing as there was likely a bad reason why he remembered

it. At least when I joined, he had no

excuse not to know my name.

birthday, some of the amusing stories about him from Fire Men come to mind.

His first actual fire call changed

him for life, but not in the dramatic way some might think. In the middle of the night, he woke up to the

siren wailing in the distance, down over the hill. He quickly got out of bed and dressed, racing

to the car. He sped toward the station,

less than a mile from the house, impressed with his reaction time and rapid

response to the emergency call.

When he got

to the station, he found he was a bit behind the curve. Numerous cars were already there, and all of

the fire apparatus—two pumpers and a squad truck—were already gone. Luckily, the call was only right down the

street; he could see the flashing lights at the nearby bank. Driving the short distance, he saw the

apparatus positioned around the building and ground ladders raised to the

roof. The fire was minor in nature, but

he quickly figured out he needed to pick up the pace if he ever hoped to make

it onto one of the fire trucks.

After that,

Dad became an efficiency expert’s dream.

Clothes were carefully laid out on the bureau each night before

bedtime. Keys, glasses, and cigarettes

were strategically positioned. The most

radical idea was yet to come: an automatic garage door opener. Those were unheard of in our neighborhood,

but Dad took it to the next level. Most

garage door openers, even today, have the button that activates them in the

garage next to the car. That wasn’t

enough for Dad. He put an additional

button in the closet in the bedroom which allowed him to hit the button while

getting dressed. The garage door would

already be open when he reached the garage, saving a good five seconds. A NASCAR pit crew would be impressed with his

speed out of the house. When I was about 11 years old, we moved to a new house

in a nearby neighborhood. One of the

first things wired in was the activation button for the garage door opener in

the closet of the master bedroom.

In the mid-1960s, a massive

technological advancement happened—Plectrons became available. Plectrons were tone-activated radio receivers

manufactured by the Plectron Corporation.

As far as firemen were concerned, they were the greatest thing since

sliced bread. Now they knew exactly

where and what type of fire they were going to.

The name Plectron for a tone-alerted receiver became the fire service

equivalent of Xerox for copiers.

The

original models weren’t even solid state, instead they used tubes. The warmth from the tubes made them

attractive to animals. My cat loved to

sleep on top of the Plectron because of the heat it emitted. The cat loved it

until the high pitched squealing tone alert went off at full volume. Then he would jump simultaneously up from the

radio and off of the top of the refrigerator upon which it sat. It was a sight to behold.

Because of

all this, as a young boy, the importance of speed out the door was ingrained in

me. When relatives visited, I knew to

advise them of safety measures I had developed out of necessity. If the tones went off, I would yell “quick,

Grandma, get in a chair! He’ll trample

you.” This came from the experience of

being treated as a track hurdle while playing with toys on the floor when a

fire call happened to come in.

To say that Dad could be a little

bit anal about equipment organization would be putting it mildly. I think it was the ex-Marine in him coming

out.

Our engines

varied in vintage from 1957 to 1975 back when he was a chief in the 1970s and

80s. What didn’t vary is where things

were located. You could open any

compartment on any of the four engines (three first line and one reserve) and

each piece of hardware, nozzle, appliance, wye, gate valve, etc., would be

found in exactly the same spot on every piece.

Hose was a

pet peeve of his. We had a spare load of

hose for each engine stored in doughnut rolls on hose racks in the rear of the

building. I would catch him regularly

rearranging the hose on the racks so the end butt of each roll was in perfect

alignment.

If he saw

you put a roll of hose on the racks and not line up the butt with the adjacent

ones, you would hear about it instantly.

This was not one of his saner practices.

Dad was

terrible with names. Guys in the

department upwards of five years were “hey you.” If he did know your name in less time, it was

not necessarily a good thing as there was likely a bad reason why he remembered

it. At least when I joined, he had no

excuse not to know my name.

Published on September 09, 2012 06:36

September 3, 2012

“Quarterback” Size-up

The start of football season

brings out the talking heads and sports commentators who spend an inordinate

amount of time talking about the mental skillset necessary to play the position

of quarterback at a high level; making it sound like the most difficult job on

earth. While admittedly I have no desire

to stand in front of a snarling 350 pound lineman trying to make my body

intimate friends with the grass, I do think that the situational awareness

necessary for rapid decision making under center presents some interesting

parallels to fire scene size-up. With a

pass play called, quarterbacks go to the line of scrimmage and see a defensive

formation that may give an accurate representation of the opposition’s

intentions or may be deceptive. At the

snap, he has a few short seconds to read the scene and hopefully be able to

locate and connect with his primary receiver.

If covered, he then has to check down and look for his secondary or

tertiary outlet. He has to avoid getting

tunnel vision as the defense converges and move, bob, and weave while

continuing to look down field; big picture and small, refining his tactics based

on what he sees.

The first arriving fire officer

on a residential structure fire faces similar challenges. What “formation” is the fire showing and is

it deceptive or obvious. In just a few

seconds, the officer needs to evaluate the construction, occupancy, exposures;

read the smoke and extent of the fire conditions present on all those. He can then audible his strategy and the

associated tactics. The firefighters

under him have a similar complex job to do looking at primary and secondary

escape routes and continually evaluating the effect that the fire is having on

the structural integrity of the building so they too can check down and adjust

their attack and team actions if necessary.

The similarities are obvious

although the salary levels are not. The

stakes on the correct decision making on the fire side are a little higher than

a sack, incomplete pass or interception.

Published on September 03, 2012 07:28

August 31, 2012

A Recent Interview by Author Pat Bertram

Gary Ryman, Author of “Fire Men: Stories From Three Generations of a Firefighting Family”

August 28, 2012 — Pat Bertram

What is your book about?

What is your book about?

Fire Men: Stories From Three Generations of a Firefighting Family relates the experiences as firefighters of my father, myself, and my son. As both the son and father of firefighters, I bring a different perspective. Having the opportunity to fire fires, with both my father and my son as well as respond to auto accidents, and the myriad other emergencies that fire departments handle was marvelous.

How long had the idea of your book been developing before you began to write the story?

I can’t say it really started in my mind as a book. I began writing out the stories of individual emergency calls with the thought that perhaps sometime in the future the vignettes might be of interest to my son or daughter or perhaps a future generation. After I had a hundred plus pages of this material, it dawned on me that perhaps this was a book trying to get out.

How long did it take you to write your book?

About four years from pen touching paper to holding the first printed copy. The first draft took just over a year. It wasn’t remotely ready, but I didn’t know that at the time, and with the encouragement of some friends, I began the querying process. One of the agents I wrote had represented an author I liked a great deal. A few weeks after sending my letter, I received an email from another agent at that firm indicating that the first agent was not interested; but that my query had intrigued her and she wanted to read the manuscript. After reading it, she agreed to work with me and provided incredibly valuable feedback and suggestions which I incorporated in a second draft. A few more rounds of revisions followed and just before she was ready to start sending the manuscript out, I was orphaned—she left to take a job as an editor at one of the big six houses. Not surprisingly, the agent she passed the manuscript who decided it wasn’t for him, and so I was back to square one, albeit with a much improved book. This time, along with agents, I looked at small publishers as well, and was lucky enough to hook up with a wonderful publisher, Tribute Books http://www.tribute-books.com/ They have since transitioned to YA books, but continue to strongly support their entire list, and have been just fantastic to work with.

What is your goal for the book, ie: what do you want people to take with them after they finish reading the story?

For many, whom the closest they have ever been to a fire truck is when it passes them on the roadway, I hope they get an understanding of what firefighting is really like. The mental and physical challenges, along with the emotional aspects of the job are not usually apparent to the general public. In addition to those, the family facets lend an important component. While I worked with my father and son, I also had many brothers; fellow firefighters who you trust with your life. For those in the fire service, the greatest compliments I receive are those that read it and say “yeah, that’s exactly how it is.”

What are you working on right now?

I just submitted my thesis for my Masters in American History. That has been consuming me for most of the past nine months. Now I hope to return to the novel I began shortly after publication of “Fire Men” which is an action adventure genre work, naturally set in a fire department. A Lieutenant dies while battling a fire which was deliberately set in an insurance fraud scheme and his best friend and brother-in-law who leads a ladder company in the same department searches for the arsonist.

What do you like to read?

I read mainly history or action/adventure.

Where do you get the names for your characters?

When I wrote the book, I used real names to allow me to keep track of people and try to ensure I captured their personalities. In the revision process, though, the majority of the names had to be changed. I stole an idea from a writer’s seminar I attended, and bought a baby name book, and reworked the names from that.

If your book was made into a TV series or Movie, what actors would you like to see playing your characters?

While I can’t say for everyone in the book, I would certainly be willing to settle for being played by Brad Pitt. The resemblance (not) is so close!

Who designed your cover?

The publisher took care of the cover, and I think did an incredible job. I was stunned the first time I saw it, and could not have been happier.

Where can people learn more about your books?

Folks can visit my website for more information. The book is also available in paperback on Amazon.com as well as Barnes & Noble and in virtually all e-book formats.

Folks can visit my website for more information. The book is also available in paperback on Amazon.com as well as Barnes & Noble and in virtually all e-book formats.

http://fire-men-book.blogspot.com/

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0982256590/ref=s9_simh_gw_p14_d0_i1?pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_s=center-2&pf_rd_r=0CM4CBCA5H4DWQXT1Y38&pf_rd_t=101&pf_rd_p=1389517282&pf_rd_i=507846

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fire-men-gary-r-ryman/1100719030?ean=9780982256596

http://patbertram.wordpress.com/2012/08/28/gary-ryman-author-of-fire-men-stories-from-three-generations-of-a-firefighting-family/#comment-2906

August 28, 2012 — Pat Bertram

What is your book about?

What is your book about?Fire Men: Stories From Three Generations of a Firefighting Family relates the experiences as firefighters of my father, myself, and my son. As both the son and father of firefighters, I bring a different perspective. Having the opportunity to fire fires, with both my father and my son as well as respond to auto accidents, and the myriad other emergencies that fire departments handle was marvelous.

How long had the idea of your book been developing before you began to write the story?

I can’t say it really started in my mind as a book. I began writing out the stories of individual emergency calls with the thought that perhaps sometime in the future the vignettes might be of interest to my son or daughter or perhaps a future generation. After I had a hundred plus pages of this material, it dawned on me that perhaps this was a book trying to get out.

How long did it take you to write your book?

About four years from pen touching paper to holding the first printed copy. The first draft took just over a year. It wasn’t remotely ready, but I didn’t know that at the time, and with the encouragement of some friends, I began the querying process. One of the agents I wrote had represented an author I liked a great deal. A few weeks after sending my letter, I received an email from another agent at that firm indicating that the first agent was not interested; but that my query had intrigued her and she wanted to read the manuscript. After reading it, she agreed to work with me and provided incredibly valuable feedback and suggestions which I incorporated in a second draft. A few more rounds of revisions followed and just before she was ready to start sending the manuscript out, I was orphaned—she left to take a job as an editor at one of the big six houses. Not surprisingly, the agent she passed the manuscript who decided it wasn’t for him, and so I was back to square one, albeit with a much improved book. This time, along with agents, I looked at small publishers as well, and was lucky enough to hook up with a wonderful publisher, Tribute Books http://www.tribute-books.com/ They have since transitioned to YA books, but continue to strongly support their entire list, and have been just fantastic to work with.

What is your goal for the book, ie: what do you want people to take with them after they finish reading the story?

For many, whom the closest they have ever been to a fire truck is when it passes them on the roadway, I hope they get an understanding of what firefighting is really like. The mental and physical challenges, along with the emotional aspects of the job are not usually apparent to the general public. In addition to those, the family facets lend an important component. While I worked with my father and son, I also had many brothers; fellow firefighters who you trust with your life. For those in the fire service, the greatest compliments I receive are those that read it and say “yeah, that’s exactly how it is.”

What are you working on right now?

I just submitted my thesis for my Masters in American History. That has been consuming me for most of the past nine months. Now I hope to return to the novel I began shortly after publication of “Fire Men” which is an action adventure genre work, naturally set in a fire department. A Lieutenant dies while battling a fire which was deliberately set in an insurance fraud scheme and his best friend and brother-in-law who leads a ladder company in the same department searches for the arsonist.

What do you like to read?

I read mainly history or action/adventure.

Where do you get the names for your characters?

When I wrote the book, I used real names to allow me to keep track of people and try to ensure I captured their personalities. In the revision process, though, the majority of the names had to be changed. I stole an idea from a writer’s seminar I attended, and bought a baby name book, and reworked the names from that.

If your book was made into a TV series or Movie, what actors would you like to see playing your characters?

While I can’t say for everyone in the book, I would certainly be willing to settle for being played by Brad Pitt. The resemblance (not) is so close!

Who designed your cover?

The publisher took care of the cover, and I think did an incredible job. I was stunned the first time I saw it, and could not have been happier.

Where can people learn more about your books?

Folks can visit my website for more information. The book is also available in paperback on Amazon.com as well as Barnes & Noble and in virtually all e-book formats.

Folks can visit my website for more information. The book is also available in paperback on Amazon.com as well as Barnes & Noble and in virtually all e-book formats.http://fire-men-book.blogspot.com/

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0982256590/ref=s9_simh_gw_p14_d0_i1?pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_s=center-2&pf_rd_r=0CM4CBCA5H4DWQXT1Y38&pf_rd_t=101&pf_rd_p=1389517282&pf_rd_i=507846

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fire-men-gary-r-ryman/1100719030?ean=9780982256596

http://patbertram.wordpress.com/2012/08/28/gary-ryman-author-of-fire-men-stories-from-three-generations-of-a-firefighting-family/#comment-2906

Published on August 31, 2012 04:40

Gary R. Ryman's Blog

- Gary R. Ryman's profile

- 3 followers

Gary R. Ryman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.