Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 23

July 24, 2013

It can happen! A visit with good communication and what it taught me

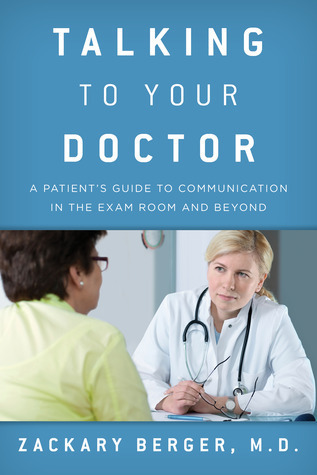

Crossposted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

I dwell so often in this space on the things that doctors and patients get wrong that I feel obligated to tell a good story, about a 43-year-old lady from Panama that I saw this week. She’s a regular patient of mine [whose identifying details, obviously, are changed]. We had a long chat about her lung disease, heart failure, depression, and hip arthritis.

She got my attention right when she sat down. “I’m going to talk your ear off today,” she said, looking guilty.

“That’s the way I like it,” I responded cheerily – or, at least, I hope I was cheery.

Then she proceeded to tell me a lot about her symptoms, what she did about them, and whether she had chosen, or not, to take the medication I had prescribed. I was in patient-centered heaven. I didn’t have to prompt her at all, just sit back, type, and listen.

As she was about to leave my office, she made another remark. “I had to train myself to talk to you. I had to get used to you but now I know what to say.”

Train herself: she paid attention to what she had to say, and practiced so as to get it into the form I would pay attention to.

Had to get used to me: I am not the world’s perfect listener. I have my own quirks and foibles. My patients will have to get used to those, just like I have to get used to theirs.

Knows what to say: She now has some level of confidence that she is communicating well.

Now that’s a good visit! Let’s hope she actually feels better, the next time I see her, after pursuing the treatment we agreed on.

July 23, 2013

Asking something about the other person: what doctors and patients have in common

Crossposted, as you should know by now, to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

One of the many useful pieces of advice to doctors that Atul Gawande proffers in the last chapter of his Better is that a doctor should ask every patient about something in their lives unrelated to their health complaint. Of course, this can easily give rise to unintended consequences. I asked one patient of mine, a guy in his fifties with an accent from the Maryland shore, what he liked to do with his time. “I like to race horses,” he said, and when I was surprised that he didn’t seem the jockey type he made it clear that he played horses. Or, rather, gambled on horses. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it might not have been a personal interest he would have shared with me otherwise.

Sometimes I wonder whether patients are going to ask me about my life. They ask about my kids, which is generally a safe topic, but not much more. It’s clear why: doctors and patients are careful about boundaries for good reason. We are partners in health, ideally, but not friends or relations.

In the healthcare encounter, however, we have a lot more in common than we might realize.

We both think we know more than we actually do. Doctors like to assume they act based on evidence, when mostly they (we) don’t, or the evidence is incomplete. Patients think they know their bodies – and they do, they are the ones most familiar with them. But knowledge of one’s own body doesn’t necessarily entail a prediction of what a set of symptoms might mean. We each need the other to be informed and educated out of our complacency.

We think the other is not doing a good job. Doctors roll their eyes at patients who don’t take their medications exactly as directed, even though doctors – playing the role of patients – do exactly the same thing. And the reason patients don’t take medications is not just to be ornery or contrary: it’s because they don’t know how; are worried the medication might be making things worse; can’t afford to fill the prescription; or are afraid to tell the doctor they don’t agree. By the same token, doctors are put in a spot by patients assuming the absolute worse the minute they enter the exam room.

Maybe, then, doctors and patients should start asking about each other’s lives more often (on suitably inoffensive topics, of course, like kids, favorite desserts, weather, and vacation plans). There is plenty of common ground. Perhaps we can expand it.

July 22, 2013

Two planets of healthcare: the patient’s view

Cross posted at Talking To Your Doctor, the blog.

In a recent article in the New York Times, the prolific Danielle Ofri makes the point that inpatient and outpatient medicine are so different as to be on different planets. She’s right, of course. In the hospital, illness is more acute and everything needs to be done faster. More resources are used. Life or death can often hang on every day’s decisions. In the clinic, most things are slowly developing, many things get better on their own, and decisions are less weighty.

Or that’s what we think. From a patient’s point of view, the hospital and the clinic share many similarities:

1. The language can be bewildering.

2. No one spends enough time.

3. Decisions are made without asking you.

4. You are given medications without full information or the chance to say no.

5. People process you without introducing themselves.

6. You are made to dress and undress at the drop of a hat.

7. Everything costs too much, and it’s hard to figure out why.

8. There’s nowhere to put your kids.

9. If you speak another language, you have to wait for an interpreter – or sometimes you don’t get one at all.

10. You are too confused, or sick, to think straight, but sometimes you are expected to share in the decision as if you are fully empowered.

11. You wait and wait for your questions to be answered.

Ofri’s point is that, once upon a time, the same doctor would see patients in the hospital and in the office. Nowadays, it’s most common for special doctors to see patients in the hospital, and other doctors, of the outpatient variety, to see them outside. The technical requirements of the two environments are two different for one doctor to be able to deliver good care in both.

What does it tell us, though, if the experience of the patient is similar in important ways in the two environments? Does it mean that the right kind of doctor can provide superior care to patients in the hospital and the office? Does it mean the care needs to be reshaped, in equally serious fashion, in both places? What do you think?

July 19, 2013

Friday cat blogging – in the exam room

Cross-posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

Like anybody, I have particular favorites among people I work with. I try to give the best care to every single person in my practice, but I can’t deny there are people whose name on the schedule makes me smile. Today, I saw Ms. Mallory, not her real name. She’s a dynamo – I wish I could tell you about her historical importance and her artistic talents, but then I would be identifying her and running afoul of various rules and regulations. So I’ll stick to her cats. She has five of them.

Like people with five kids, she is always running from one appointment to another with one or more in tow. One of them had to go to the dermatologist the other day; the other had a general veterinarian appointment. A third needed grooming. And so it went. “I’m exhausted taking care of them!” Ms. Mallory told me, with a proud smile.

She’s a little mysterious, and I find it hard to put a finger sometimes on what’s bothering her. Many doctors call this “being a poor historian” but that phrase rankles me no end. Telling a good story about our symptoms is important (I discuss the reasons why at some length in my book), but often this phrase is a condescending excuse why the provider isn’t listening to the patient.

Often, then, I find myself wishing I knew what was really going on with her. Ms. Mallory has her ups and downs, and her chronic medical conditions which makes it all more complicated. When she’s in these peaks and valleys – some physical, some emotional – I would give anything for a deeper sense of her days and nights. To be more precise, I would love to interview her cats. Only they have a close-up view of her inner life. And, just like a wife or a husband, they know what it’s like to care for and be cared for by the person they live with.

I don’t do home visits. Even if I did, I wouldn’t get the whole picture from a half-an-hour visit. I’d really need to be part of Ms. Mallory’s inner circle to know what makes her feel better or worse. In other words, I would need to be a cat. Or speak feline. Neither of which are yet taught in veterinary schools.

July 18, 2013

We’re number one . . . again. But what does that mean?

Cross-posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

Let’s share the glad tidings: Johns Hopkins is again ranked as the number-one hospital in all the land. I’ve written about this before, sharing my misgivings about ranking hospitals. What is the methodology? How sensitive is the ranking to random error, bias, and qualities of hospitals that have nothing whatsoever to do with their – quality, like reputation? What are we supposed to do with that information, who really uses it, and do they get better care as a result?

There are enough misgiving here to fill several chapters of a book, and in fact one chapter of mine is devoted to them. But the problem with measuring extends far past the ranking of hospitals. Doctors are being ranked this way, too, with the idea that public reporting of such information will help people make better choices about their health.

At the same time, many are trying to urge our health care system towards greater patient-centeredness. Various research teams are developing measures to quantify how well a given visit with a physician enables shared decision making on the part of the patient-doctor pair.

So, when presented with an array of various numbers – the rank of the hospital; the quality of the doctor; and the patient-centeredness of the practice – which one should the patient choose? Do we ask patients, as a whole, which ranking they find more important? Is each person to mix up a batch of numbers to find whatever aggregate satisfies their preference?

These are big questions. As I outline in my book, there is evidence that precious few patients or doctors actually use these rankings. Perhaps if we include patient-centeredness in the mix, and automatically generate a weighted average (or some other statistical combination of measures) that corresponds to patients’ preferences, people will feel like they are getting the best doctor they can find. That would be something to truly celebrate.

July 17, 2013

Slave doctors and slave patients: Plato on autonomy and what we can learn from it today

Cross-posted at the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

Thanks to Matthew Wynia at the American Medical Association who distributed to a group I’m involved with the following quote from the Dialogues of Plato about doctor-patient communication. I believe the translation is from Jowett, 1937, but I’m not sure.

In the LAWS, Book 4 [says Wynia in a summary], we have the following discussion between the Athenian and Cleinias regarding patients lacking autonomy (because they are ruled by others) and autonomous (self-ruling) patients.

The Athenian asks: “You are aware that there are these two classes of doctors?”

Cle. To be sure.

Ath. And did you ever observe that there are two classes of patients in states, slaves and freemen; and the slave doctors run about and cure the slaves, or wait for them in the clinic. They never talk to their patients individually, nor do they allow them to talk about their own individual complaints. The slave doctor diagnoses and prescribes a remedy on an empirical basis, [but does so] as if he had exact knowledge; He gives his orders [to the patient], like a tyrant, and then rushes off, to see some other slave who is ill, all the while projecting an air of confidence and assurance;…

But the other doctor attends and practises upon freemen; and he carries his enquiries [with his patient] far back, and goes into the nature of the disorder in a scientific way; he enters into discourse with the patient and with his family, and is at once getting useful information from the sick person, and also instructing him as far as he is able. [The physician] will not prescribe for the patient until he has first convinced him; at last, when he has brought the patient more and more under his persuasive influences and set him on the road to health, he attempts to effect a cure.

Now which is the better way of proceeding in a physician and in a trainer? Is he the better who accomplishes his ends in a double way, or he who works in one way, and that the ruder and inferior?

Cle. I should say, Stranger, that the double way is far better.

There is much to note here. First is the distinction between slaves and freemen, not just among patients but among physicians. And the two are paired: a slave doctor deserves, so to speak, a slave patient – or perhaps the two are yoked together, each deserving no better than the other. For Plato, as we know from the Republic, is wedded to the hierarchy.

We can take away at least two lessons to our own day. First is that our care, in our enlightened republican democracy of the U.S. as much as in Greece, is inseparable from the economic stratum of its provision. It is a universally known but much hidden and ignored truth that the poorest and disadvantaged get the least care, a problem I discuss at length in my book. Further, though, we can read the terms “slaves” and “free [people]” more broadly. When a patient and provider can look beyond what others have called the “tyranny of the acute” and focus on the deeper issues that affect health, both become free to find the cure at the end of healing.

That, in closing, is the idea that fascinates me the most here. While, in my practice today, I think about treatment as inseparable from a cure (thinking about a correct treatment entails considering a cure), the account in the Laws seems to suppose something else. Only once a patient is on the “road to health” can the physician “effect a cure.” I am not sure how to take this, but I find attractive the notion of cure as a process brought about by a long-term relationship between doctor and patient.

July 16, 2013

“Give me my damn data”: but is that enough?

There are plenty of books out there to teach us how to boldly and proudly advocate for ourselves in the doctor’s office. Doctors have held the reins too long, goes the story, and ignored what patients want and need. So it’s time for patients to step up and ask for what we deserve. If there are medications prescribed, we should know how, when, and why. If there are tests to be ordered, we should have the results in hand. We should even have unfettered access to our medical records—this last expectation has a slogan attached, too: “Give me my damn data!”

But is open data the key to improved health? Check out the excerpt from Talking To Your Doctor at KevinMD.com.

When a doctor knows he’s doing the wrong thing

There are times when a doctor knows he’s doing the wrong thing and does it anyway. I’ve done it quite often. This happens when I order laboratory tests for no good medical reason. I am ordering them just to help my patient get their operation or procedure.

Read more at the Minimally Disruptive Medicine blog.

July 15, 2013

How do we remake our health care system on the basis of relationships and communication? (Or: tomorrow is publication day!)

Cross-posted as usual to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

The last chapters of my book propose remaking our health care system on the basis of good communication and positive relationships with our doctors (and nurses, and physician assistants). How do we get to a changed system on the basis of individual behavior? Isn’t that unrealistic, even naive?

Remaking our system is a noble, grand struggle, one of the most important tasks for this century. Remaking is already going on in different ways. Obviously, there is health care reform, by which is meant legislation and executive action. This is, mostly, top down. I am not a libertarian: there is nothing I find philosophically inimical about top-down change. Health care is huge and someone has to flip the master switches.

At the same time, however, change has to come from the bottom. Patients are their own people with adequate decision-making capacity: can you believe that some doctors are only just coming around to this truth? But how do we get the system to embody this truth? We can not legislate shared decision making and patient-centeredness; nor can we merely, by fiat (as some e-patients are doing), say that patients are now the owners of the store.

Patients should be the owners of the store, together with their doctors, but just proclaiming that in a loud voice won’t get you anywhere. Some of us live out in the woods, where Internet calls-to-action don’t carry, and some others of us are too disempowered or intimidated to take charge in our doctors’ offices even if we are given permission to by those well-spoken advocates.

I like to make the comparison to the struggle for civil rights, which I am no historical expert in (so correct me if I am wrong). That struggle’s success was dependent on both legislative action and bottom-up activism, each of which informed the other. The exercise of the right to vote would not have been possible without the Voting Rights Act. The Voting Rights Act would not have worked without protests.

There is a place for health care reform to encourage primary care providers to establish a relationship with patients, and vice versa. But the importance of communication to such an endeavor, I can’t help but think, is not something that will come out from Washington. That will have to bubble up out of each exam room individually.

Tomorrow’s the big day! Please – if you have read the book already – review it on Amazon or Goodreads. If you haven’t read it, you are warmly invited to do so. Even more important than buying the book is letting me and others know what you think about it.

July 12, 2013

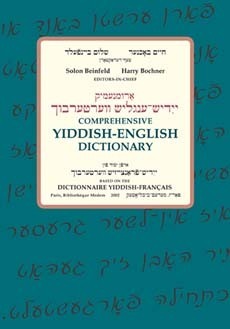

How Can Yiddish Literature Be Translated?

Chaim Grade’s works are waiting. Is a new dictionary enough?

For as long as people have read and written Yiddish literature in the modern era, they have taken pains to translate it into other languages, as if they could not be sure that the language they were writing in would be read when they were finished. Sholem Aleichem translated himself in his own lifetime. His fiction has lived to be told and retold on the stage and between covers – but is rarely read now in Yiddish. Generations of readers in English, Russian, and Hebrew are surprised to hear that that their loved Tevye did not speak their language.

But for every writer who has translated themselves, or been translated, there are a dozen writers who have not. For example, Chaim Grade, one of the 20th century’s greatest Yiddish writers, produced a large amount of work, much of which – due to this opposition of his wife – has not been translated into English. Only with the disposition of his estate, which has now been bought by the YIVO and the National Library of Israel, will he finally be translated in a large scale. But how do make sure translation actually happens – and how do we make sure there are enough translators to take on the work of rendering these and thousands of important works into English?

Luckily, there appears to be an increasing interest in this craft of translation, and of Yiddish especially. Of course, this interest is hardly a mass-market phenomenon. While Yale University Press, together with the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, started a series of New Yiddish Literature, meant to showcase high-quality literary translations, the series had to shutter because of low readership. The Book Center has also started an initiative to promote translations from Yiddish, with the first crop of half-a-dozen fellows chosen this year.

There isn’t any evidence that masses of young Jews are suddenly streaming to the Yiddish stacks of their local libraries. But If few people are reading Yiddish literature now as ever, what drives people to translate from Yiddish, and what is their motivation? Can we tap into whatever is driving such eminent translators of Lawrence Rosenwald, a professor of English at Wellesley College and the translator of an upcoming volume of stories by Lamed Shapiro, the prose portraitist of Jewish urban disillusionment? He was a literary translator from French, Italian, and German before he tried his hand at translating from Yiddish, for the same reason he had translated other texts before: “translating a text [is] the most powerful way of deepening that engagement [with it], dealing with the whole text and not just the parts you like.” He became a Yiddish translator by happenstance, when a fellow reader of Yiddish recommended a story to him that upended his expectations.

Like Rosenwald, translators are readers in both the source and the target language, points out Susan Harris, editor of the translation website Words without Borders and a doyenne of the community of literary translation. Rosenwald, an academic, is an example of a person with relatively stable employment who can devote time to translations. But where will other new Yiddish translators come from? They will have to be those who read Yiddish literature already: either graduate students, for whom a translated literary work is no route either to a PhD or respect (let alone tenure) in the world of academia, or Charedim, who might not command a literary knowledge of English.

The lack of new translators, says Harris, can be addressed from two directions: training, for example in universities and graduate programs, as well as summer workshops, and funding – again, either from academia or philanthropy. If, however, Jewish education is chronically underfunded, who can we expect to step up and support the translation of Yiddish literature, when Hebrew literature – to make a comparison – is not represented either on American bookshelves apart from a few well-worn names?

One bright spot should however be noted. The shelves are chockablock with new volumes, armaments in the only arsenal that really matters to the translator: her dictionaries. There have been new dictionaries from Yiddish and French and Yiddish to Russian, and a dictionary of the loshn-koydesh (Rabbinic Hebrew and Aramaic) – derived words in Yiddish.

Most of these dictionaries are thanks to, either originally or derivatively, the work of Yitzkhok Niborski, whose Yiddish-French dictionary, published by the Medem Library in 2002, achieved a high-water mark in post-war Yiddish lexicography. While the beloved Uriel Weinreich Yiddish-English English-Yiddish dictionary was designed for students, Niborski’s goal was to provide a more complete list of those words to be found in Yiddish literature.

So the newest tool for translators, academics, and those few casual readers of Yiddish literature, the Comprehensive Yiddish-English Dictionary edited by Solon Beinfeld and Harry Bochner and published in 2012 by Indiana University Press, is certainly to be welcomed and has already been hailed as a work of high quality and immediate usefulness. Unlike Weinreich’s Dictionary, it is not blinkered by prescriptivism, nor hindered by a misplaced delicacy and a desire to “whitewash” the dirty parts of Yiddish. (I can’t be the only one who looks up the four-letter words in any new dictionary he opens, and this one does not systematically exclude them as did Weinreich.)

if we think of Yiddish literature as a closed canon to be mined, its treasures brought up above ground and appreciated in the bright light of English, this dictionary is the ideal tool. However, if we understand any translation as one point in the continuum between one language and another, readers in Yiddish and English whose discoveries enrich each other’s communities, then this dictionary, for all its rigor, clarity, erudition, and usefulness, might fall short.

The reason is that a number of contemporary Yiddish words of wide provenance are simply missing. There is no internet, no diner [fundraising dinner], no bulshit. There is no vebzaytl. The absence of these words is not necessarily a fatal flaw – this is not an all-encompassing Grand Yiddish Dictionary, a project which has been abandoned too many times to count – but it does indicate the priorities of the compilers. And it indicates that today’s translators of Yiddish literature might lack a vital link to today’s Yiddish-language speech community.

Why is this important? Because the third supporting element to attract a wider audience to Yiddish literature, besides translators and dictionaries, is readers – in both English and Yiddish.

Without readers and writers in the original language, it is difficult to maintain a critical mass of appreciative ears and eyes which take the original to translation and then, ideally, back again to the source language to seek new sources of flavor and interest to the outside reader.Harris says, “Without readers of, and translators from, the original language, little or nothing is translated, which means there’s nothing to lure readers or students, or to motivate them to learn the language; and that perpetuates the invisibility. “

How do we attract readers to a language and a literature they do not know, either because they don’t know people write secular literature in Yiddish or because they don’t know Yiddish itself? How is their attention to be attracted in a world of infinite amusements and literary output? What is the “pitch” to entice potential readers of Yiddish? Is it a literature of global importance waited to be sprung upon an unknowing world, or a wholly owned subsidiary of Jewish culture, only of interest to Judeophiles and their friends?

Perhaps, hiding in the Yiddish stacks of some university library, the next psychologically acute novel or eye-opening poetic epic is waiting to be discovered, if only we could get enough readers of Yiddish to open up those books, and open up the channels between English and Yiddish, so that translations could flow through them and irrigate the surrounding fields of Jewish thought and literature.