How Can Yiddish Literature Be Translated?

Chaim Grade’s works are waiting. Is a new dictionary enough?

For as long as people have read and written Yiddish literature in the modern era, they have taken pains to translate it into other languages, as if they could not be sure that the language they were writing in would be read when they were finished. Sholem Aleichem translated himself in his own lifetime. His fiction has lived to be told and retold on the stage and between covers – but is rarely read now in Yiddish. Generations of readers in English, Russian, and Hebrew are surprised to hear that that their loved Tevye did not speak their language.

But for every writer who has translated themselves, or been translated, there are a dozen writers who have not. For example, Chaim Grade, one of the 20th century’s greatest Yiddish writers, produced a large amount of work, much of which – due to this opposition of his wife – has not been translated into English. Only with the disposition of his estate, which has now been bought by the YIVO and the National Library of Israel, will he finally be translated in a large scale. But how do make sure translation actually happens – and how do we make sure there are enough translators to take on the work of rendering these and thousands of important works into English?

Luckily, there appears to be an increasing interest in this craft of translation, and of Yiddish especially. Of course, this interest is hardly a mass-market phenomenon. While Yale University Press, together with the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, started a series of New Yiddish Literature, meant to showcase high-quality literary translations, the series had to shutter because of low readership. The Book Center has also started an initiative to promote translations from Yiddish, with the first crop of half-a-dozen fellows chosen this year.

There isn’t any evidence that masses of young Jews are suddenly streaming to the Yiddish stacks of their local libraries. But If few people are reading Yiddish literature now as ever, what drives people to translate from Yiddish, and what is their motivation? Can we tap into whatever is driving such eminent translators of Lawrence Rosenwald, a professor of English at Wellesley College and the translator of an upcoming volume of stories by Lamed Shapiro, the prose portraitist of Jewish urban disillusionment? He was a literary translator from French, Italian, and German before he tried his hand at translating from Yiddish, for the same reason he had translated other texts before: “translating a text [is] the most powerful way of deepening that engagement [with it], dealing with the whole text and not just the parts you like.” He became a Yiddish translator by happenstance, when a fellow reader of Yiddish recommended a story to him that upended his expectations.

Like Rosenwald, translators are readers in both the source and the target language, points out Susan Harris, editor of the translation website Words without Borders and a doyenne of the community of literary translation. Rosenwald, an academic, is an example of a person with relatively stable employment who can devote time to translations. But where will other new Yiddish translators come from? They will have to be those who read Yiddish literature already: either graduate students, for whom a translated literary work is no route either to a PhD or respect (let alone tenure) in the world of academia, or Charedim, who might not command a literary knowledge of English.

The lack of new translators, says Harris, can be addressed from two directions: training, for example in universities and graduate programs, as well as summer workshops, and funding – again, either from academia or philanthropy. If, however, Jewish education is chronically underfunded, who can we expect to step up and support the translation of Yiddish literature, when Hebrew literature – to make a comparison – is not represented either on American bookshelves apart from a few well-worn names?

One bright spot should however be noted. The shelves are chockablock with new volumes, armaments in the only arsenal that really matters to the translator: her dictionaries. There have been new dictionaries from Yiddish and French and Yiddish to Russian, and a dictionary of the loshn-koydesh (Rabbinic Hebrew and Aramaic) – derived words in Yiddish.

Most of these dictionaries are thanks to, either originally or derivatively, the work of Yitzkhok Niborski, whose Yiddish-French dictionary, published by the Medem Library in 2002, achieved a high-water mark in post-war Yiddish lexicography. While the beloved Uriel Weinreich Yiddish-English English-Yiddish dictionary was designed for students, Niborski’s goal was to provide a more complete list of those words to be found in Yiddish literature.

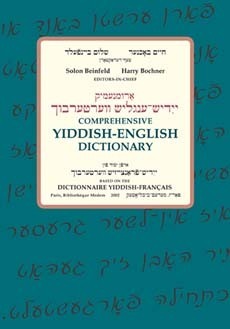

So the newest tool for translators, academics, and those few casual readers of Yiddish literature, the Comprehensive Yiddish-English Dictionary edited by Solon Beinfeld and Harry Bochner and published in 2012 by Indiana University Press, is certainly to be welcomed and has already been hailed as a work of high quality and immediate usefulness. Unlike Weinreich’s Dictionary, it is not blinkered by prescriptivism, nor hindered by a misplaced delicacy and a desire to “whitewash” the dirty parts of Yiddish. (I can’t be the only one who looks up the four-letter words in any new dictionary he opens, and this one does not systematically exclude them as did Weinreich.)

if we think of Yiddish literature as a closed canon to be mined, its treasures brought up above ground and appreciated in the bright light of English, this dictionary is the ideal tool. However, if we understand any translation as one point in the continuum between one language and another, readers in Yiddish and English whose discoveries enrich each other’s communities, then this dictionary, for all its rigor, clarity, erudition, and usefulness, might fall short.

The reason is that a number of contemporary Yiddish words of wide provenance are simply missing. There is no internet, no diner [fundraising dinner], no bulshit. There is no vebzaytl. The absence of these words is not necessarily a fatal flaw – this is not an all-encompassing Grand Yiddish Dictionary, a project which has been abandoned too many times to count – but it does indicate the priorities of the compilers. And it indicates that today’s translators of Yiddish literature might lack a vital link to today’s Yiddish-language speech community.

Why is this important? Because the third supporting element to attract a wider audience to Yiddish literature, besides translators and dictionaries, is readers – in both English and Yiddish.

Without readers and writers in the original language, it is difficult to maintain a critical mass of appreciative ears and eyes which take the original to translation and then, ideally, back again to the source language to seek new sources of flavor and interest to the outside reader.Harris says, “Without readers of, and translators from, the original language, little or nothing is translated, which means there’s nothing to lure readers or students, or to motivate them to learn the language; and that perpetuates the invisibility. “

How do we attract readers to a language and a literature they do not know, either because they don’t know people write secular literature in Yiddish or because they don’t know Yiddish itself? How is their attention to be attracted in a world of infinite amusements and literary output? What is the “pitch” to entice potential readers of Yiddish? Is it a literature of global importance waited to be sprung upon an unknowing world, or a wholly owned subsidiary of Jewish culture, only of interest to Judeophiles and their friends?

Perhaps, hiding in the Yiddish stacks of some university library, the next psychologically acute novel or eye-opening poetic epic is waiting to be discovered, if only we could get enough readers of Yiddish to open up those books, and open up the channels between English and Yiddish, so that translations could flow through them and irrigate the surrounding fields of Jewish thought and literature.