Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 21

August 15, 2013

The two medicines

A friend wrote me after a reading:

“[W]hat I took from it is that there are indeed two MEDICINEs: the science one (read lab animals) and the humanistic one in the best tradition of Hipoocrates forward.”

The reference to “two medicines” puts me in mind of the famous essay by C.P. Snow about two cultures: the sciences and the humanities. If you read far enough down in the Wikipedia article about the concept, you see – as with so many concepts – how it becomes complicated and quibbled with out of all recognition.

Sometimes, though, quibbling misses the main point. There are those who are blind to the sciences, and those who are exclusively centered on the virtues of the humanities. Not to say that there isn’t overlap, but there should be more.

The same can be said of medicine. To be excellent professionals, doctors and nurses require both technical facility and appreciation of emotional complexity. And by “excellent” here I mean something like “virtuous,” in the sense of striving towards perfection of the whole individual.

So, when we are talking about the two medicines, perhaps we should mean that the best of the scientific/biomedical view of the patient, and the humanitarian/narrative/irreducibly complex view should both be united in the provider. If that were the case, whatever action a provider took would be in a deep sense uncategorizable.

Patient-centered care often brings the grandest flights of fancy rudely down to earth. Whether this applies to the idea of “two medicines in one provider” is difficult to say. I do think that most people are looking for a provider who combines multiple virtues: a full person, not a scientific machine nor a device to convert suffering into publishable narrative.

How to cultivate such inner diversity, true balance, without sacrificing depth and accomplishment…?

August 14, 2013

“The doctors did this to me”: but what if that’s not helpful?

A friend suggested that I should share on this blog more actual conversations with patients, and observations about what I (or another doctor, or a patient) did well or poorly – and how to do better. I did some of that in my book, albeit it is hard to do much of this without modifying the identifying characteristics of the patient and the subject of the discussion.

I will talk today about a fictionalized incident which has been repeated, in various forms, a number of times in my practice. Sarah, a 68 year old woman with chronic back pain, tells me about the terrible shooting pains she has down both legs, and the problems she has had walking over the past few months. We work up the possible causes, doing a number of blood and nerve tests, and come to the tentative conclusion that the nerve roots in her back are causing this nerve problem in her legs.

However, once we have this discussion, it rapidly becomes clear that this explanation is not uppermost in her mind, or not the most relevant. She reports that she had an operation to her lower back about five or seven years ago, and the doctor told her that there had been some error during the operation. It turns out that the error was not significant and not related to her current nerve or gait symptoms. However, at the point of these visits where we discuss the causes and potential therapies of her nerve problems, she can discuss nothing but that operation and the error.

This is of course to be expected, and I cannot ask her – nor should I – to leave this be. On the other hand, it keeps us from approaching the potential causes of her nerve pain. How do I get us past this conversation? I have done the commonsensical thing, and said, more or less, “I know this error was committed, and you have every right to feel taken advantage of, and yet….” but the message has not gotten through. I don’t feel like being more confrontational would do the trick.

Before going more into (confidentiality-respecting) detail about our relationship, and the solution I eventually embarked upon, I would like to get your thoughts. How is this impasse to be breached?

August 13, 2013

What not to call patients

There are many words that doctors have used for patients that we shouldn’t use anymore. Realizing the inappropriateness of such terminology does not require much heavy lifting – and, yet, we are still using these epithets time and time again. I thought I’d give some examples, if only to get them off my chest.

1. Non-compliant: As if the patient is supposed to be a good, obedient servant, following the doctor’s orders, turning neither to the right nor the left.

2. Denying: ["The patient denies chest pain, shortness of breath..."]: As if these are accusations, and the patient is protesting their innocence.

3. Difficult: Like a problem or a disease, the difficult patient is meant to be solved, not helped.

4. Suffering from “pseudoseizures”: If a patient has a non-epileptic, or psychogenic, seizure, there is little that’s “pseudo” about it.

5. Uncontrolled diabetic: Again the one-dimensional assessment – there is diabetes, a disease, to be controlled, but then, by metonymy, the patient becomes their disease.

What words can’t you stand when they are used to describe you, or your patients?

August 12, 2013

Patient portal powers, activate! Form of … befuddlement?

Cross-posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

My institution recently switched from its home-grown electronic medical record to EPIC, an EMR for which many great things have been promised. Indeed, it is a considerable improvement over the past system. A number of hopes have been pinned on the latest-generation EMRs, not the least of which is the idea that finally, with this newest generation of tools, a nexus can be created and sustained among comparative effectiveness research (i.e., the branch of medical science that asks which treatment are better and why), clinical care, electronic records, and patient-reported outcomes. A very recent article by my senior colleague in the School of Public Health, Albert Wu, and colleagues, traces the genealogy and current outlines of this nexus – and advises what might be necessary to move this opportunity forward.

One point he doesn’t raise in his article, however is which patients are actually using such EMRs. I was talking to a colleague the other day, and asked him idly what proportion of our patients had “activated” the code they were sent to access their patient portal into the EMR. “Twenty percent,” he sang out, and then, perhaps noting my shocked expression, quickly added, “But that’s good!”

I don’t know how good that is, but – for whatever reason – I can’t find much recent scientific literature on the prevalence of patient activation of such portals in recent years. However, a study conducted in New York City in the year 2010 published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine presents some interesting figures. Namely, that 16% of all patients in the study received an access code, and of these, 60% activated their code. Disparities were noted: those who activated their access tended to be whiter, English-speakers, and with private insurance.

Similar reports are available elsewhere, though not seemingly from much more recently [as always, I would love getting updates and will happily correct in this space]. The question remains: in any given practice, how do we make sure that the patients who are actually using the EMR faithfully reflect the composition of the entire population? If we do not somehow make these portals widely available, without disparities or inequities, we risk doing what doctors have always done: thrust health interventions at their patients without regard for accessibility or patient-centeredness, and then act cynical or walk away when patients do not snap it up with alacrity.

August 9, 2013

Pain

I think everyone who sees patients, and treats a lot of them with a particular condition, comes to see that condition as a microcosm of all of medicine. And that’s the way with me and pain. For some reason – perhaps it’s because I tend to see these patients more frequently than others – I think I have more of them.

Pain, and I mean here chronic pain, has certain characteristics which are shared with many other chronic diseases. Such elements of illness are often overlooked, and focusing on the forms they take in pain might be useful in conceptualizing them.

Often, medicines for chronic pain [as for other conditions] don’t work that well.

For many people with chronic pain there is no one “medical” cause that explains their symptoms.

Other stressors – whether psychological, psychiatric, or social – play an important role in the severity and treatment of pain, and frequently these are un- or undertreated.

Pain is a symptom experienced by nearly everyone at some time or another. Thus many people think they know what chronic pain is like. But if I’ve heard one thing from every one of these patients, the occasional bout of acute pain does not reflect the experience of chronic pain.

Do you have – or have you had – chronic pain? Do you agree with these assessments? And what should we do to improve matters?

August 8, 2013

You are there! Recording and photo from my reading on August 6th

I had a great time reading from Talking To Your Doctor at Bluestockings Bookstore and Cafe on August 6th in Manhattan. Here is a recording of the reading [warning: large file; recording thanks to Paul Glasser]. I’m introduced at around 1:00 and then I start reading at around 1:25.

Too much care for the president

George W. Bush got a stent recently. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like he needed it.

Let’s backtrack. The former president, by all accounts, was in excellent health, without reported risk factors for heart disease, and recently ran in a competitive race for charity. On a recent physical exam, though he reported no symptoms, he underwent a CT scan which showed a blockage in an artery. At that point, Bush agreed to a stent – despite the reasonably clear evidence showing that stents in people without symptoms don’t make them live longer, don’t prevent heart attacks, and (since the person starts without symptoms in the first place), don’t make anyone feel better. Except, perhaps, those who sell stents.

You can find opinions of those who are careful never to say that this might have been a mistake. Let’s not mistake the horse for a zebra, though. It seems very unlikely that this procedure was indicated. But it happened anyway.

We know about the problem of overuse already. This particular instance, like any given instance, might not have taught us any unknown facts, but it does emphasize the same questions:

1. If a former president can accede to a stent he doesn’t need, what chance do the rest of us have in avoiding overuse?

2. What were GWB’s primary care doctor and cardiologists thinking?

3. Further to number 2. – if we assume that, in fact, there were no extenuating circumstances to this case, and Bush was “overused” just like many Americans are, what is the best way to respond to a given case? Call out the involved physicians?

There must be some way to turn a much-publicized instance of contraindicated care into a turning point in the campaign to reduce overuse.

August 7, 2013

There are many book party stories in the naked city. This is one of them

Not naked, actually – that’s a relief.

There are plenty of sights and sounds that pleasurably impinged upon me during my trip to New York yesterday. I can’t report all of them. There was the exchange I witnessed at Yona Schimmel’s Knishery between a guy and a gal, a couple:

“These are kenishes,” said the guy. “You get them with fillings. Apple, kasha…”

“Oh, look,” she said. “They have egg roll filling, too.” And then, as if with a sudden realization: “Oh, honey, I want to be a counselor.”

Finally, after a pause: “I think I’d like one with mushroom.”

* * *

One of the most enlightening experiences of the day was meeting with two MPH students from CUNY, one of whom is by training a registered dietitian, the other a pediatric occupational therapist. They have had many research projects and interests among them. Enlightening, because they recognize the importance of primary care providers (really, the topic of my book – or the relationship and communication around the PCP-patient partnership), but at the same time point out how little recognition some health care workers give to others. To be frank: doctors often have no idea what therapists, nutritionists, and social workers do, much less mention them explicitly as part of the team.

Later in the day, I had the privilege of being interviewed by Barbara Glickstein, public-health nurse, activist, and co-producer of the WBAI radio show Healthstyles. She is an experienced interprofessional health educator, and I meant to bring up with her – though I didn’t – that we should expand the boundaries of such education. Students from every single health field should be able to work together in their development and simulate the complicated, sometimes trying process of working together as a team for the benefit of a single patient.

There is an axis to navigate here. On the one end is the long-term, hopefully stable relationship of primary provider and patient – and on the other, the fact that all health care workers must cooperate in such a way as to foster trust by the patient in their group effort.

August 6, 2013

Can mental health professionals have communication failures? A psychologist shares her experience

Guest post by Tamar Gordon, Ph.D. Cross-posted at the Talking To Your Doctor blog.

Recently, the parent of a 9 year old patient with an anxiety disorder was discussing with me her experience in the office of a somewhat famous child psychiatrist. I had referred the family there for a medication consultation. I knew when I referred them to the MD that that they were reluctant to consider medication, but I also knew medication might well help the child as an adjunct to the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) we were doing together.

The parent reported that she left the doctor’s office not knowing what he thought about medication. She also had not gotten to speak to him without her daughter present, though she thought she had expressly asked to do so.

I asked her what she had learned, and she said that he had confirmed her daughter’s diagnosis – which had never been in doubt! At first, I was inclined to judge the doctor harshly for his communication failure. Then I realized the same thing has happened to me. Occasionally, toward the end of a session, a patient will tell me we never discussed the major thing they had wanted to focus on. Why? What goes wrong?

I have identified at least two factors which affect the success of my communication with patients. The first is whether I have emotionally centered myself before the session to be present for that specific individual. This involves thinking about what we have talked about in the past and what we may want to talk about in the moment, and making sure that my own life is not at the forefront of my mind. Mental health professionals are human, after all, so sometimes we are distracted, tired, or less emotionally available than we want to be.

However, even when I am as perfectly present as I can be – really at the top of my game – I am not always successful. Which leads me to the second factor: conscious and willing participation by the patient.

Sometimes, patients are embarrassed to share things. Others don’t know how to explain their feelings. Sometimes people don’t want to confront the things that need to change. Bottom line – if the patient isn’t prepared to tell me, there’s not much I can do about it.

Children present an added dimension to the difficulties of communication. For example, the child in my example above shared how well she was doing with the psychiatrist, and as long as she was in the room her mother could not openly express fears and worries about her actual progress. Children have both a greater need to be liked than adults do, and less ability to think abstractly. Since children are less able to think about themselves outside of the present moment, there have to be additional sources of information. Balancing communication between the parents, school, and child is challenging.

In addition to using mindfulness to center myself before a session, another tactic which helps me avoid communication problems is setting an agenda. I ask what the patient wants to focus on, and I suggest things I’d like to discuss with them. We go back and forth for a few minutes, ascertaining what is most important so that we use our time together well. With kids I spend time with them and their parent(s) together, without their parent, and with the parent alone – giving me three tries to get the agenda right.

Why did the parents in my first story have such a tough time communicating with the child psychiatrist? It seems like the doctor was too focused on his medical evaluation to recognize that the parents were not getting what they needed, while the parents were too ambivalent and wary of contradicting an authority figure to clearly ask for what they needed. What it boils down to is that mental health professionals are subject to the same failings as anyone else, and effective communication is a skill that needs to be constantly worked on and maintained.

Tamar Gordon, Ph.D., a licensed clinical psychologist, is Voluntary Faculty at NYU School of Medicine and Adjunct Faculty, Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Yeshiva University. She has been a supervisor at a major mental health clinic, an expert consultant on trauma treatment to the United States Veteran’s Association, and is an active member of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. She currently spends most of her working time at her private practice in New York City, and most of her personal time raising her two rambunctious sons.

August 5, 2013

I don’t know and you don’t know either: uncertainty in the doctor’s office

Crossposted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

We come to the doctor’s or nurse’s office expecting to be told the truth about what is bothering us. Either we want to know that our symptoms are no sign of something serious; or, if it is in fact as bad as we were expecting, that there is a name to our pain and suffering. We would also like to know, obviously, if there is a way to be cured of whatever ails us.

We might not think about the obvious eventuality that the doctor doesn’t know the answer. (Perhaps you do, but I think that it’s often the case that we don’t.) Perhaps it’s because we factor that possibility into our decision about whether to seek medical attention in the first place. We don’t think that the doctor is infallible or always in possession of the right answer, but we are pretty sure that, with their professional training, they will be able to figure things out.

More often than not, though – as we age, confront chronic diseases, take care of relatives who are ill, or run up against the wall of providers’ imperfections, ignorance, or failure to listen – we realize that our doctors don’t know things as surely as we thought. There are many questions we have, and even of the ones that doctors are prepared to answer (which themselves are a minority), they can’t give us a clear answer.

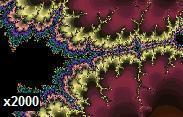

A lot in life is like this, of course: mired in uncertainty. We can have several reactions to this, in healthcare as in other areas. We can try to perfect the science, to push out the boundaries of our knowledge. Unfortunately, like a fractal landscape, the uncertainty at the border of knowledge merely shifts and curves to cover even more territory as the contacts between knowledge and ignorance lengthen.

We can declare ourselves beholden in some measure to uncertainty. If nothing is certain, empiricism is a lie, and only my truth is evident. There are some people who take that route. I think some of the anti-vaccinationists are members of this camp.

Or we can decide that certainty in knowledge is unreachable – but that uncertainty leaves space for much of what makes healthcare deliverable to people, and not to subjects of experiments or inanimate objects. It leaves room for our preferences in the face of the unknowable.

I don’t know if that is enough to cut doctors slack for what can’t be known, but maybe it can help us feel less at sea in the realm of scientific uncertainty – which is the universe, really.