I don’t know and you don’t know either: uncertainty in the doctor’s office

Crossposted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

We come to the doctor’s or nurse’s office expecting to be told the truth about what is bothering us. Either we want to know that our symptoms are no sign of something serious; or, if it is in fact as bad as we were expecting, that there is a name to our pain and suffering. We would also like to know, obviously, if there is a way to be cured of whatever ails us.

We might not think about the obvious eventuality that the doctor doesn’t know the answer. (Perhaps you do, but I think that it’s often the case that we don’t.) Perhaps it’s because we factor that possibility into our decision about whether to seek medical attention in the first place. We don’t think that the doctor is infallible or always in possession of the right answer, but we are pretty sure that, with their professional training, they will be able to figure things out.

More often than not, though – as we age, confront chronic diseases, take care of relatives who are ill, or run up against the wall of providers’ imperfections, ignorance, or failure to listen – we realize that our doctors don’t know things as surely as we thought. There are many questions we have, and even of the ones that doctors are prepared to answer (which themselves are a minority), they can’t give us a clear answer.

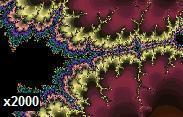

A lot in life is like this, of course: mired in uncertainty. We can have several reactions to this, in healthcare as in other areas. We can try to perfect the science, to push out the boundaries of our knowledge. Unfortunately, like a fractal landscape, the uncertainty at the border of knowledge merely shifts and curves to cover even more territory as the contacts between knowledge and ignorance lengthen.

We can declare ourselves beholden in some measure to uncertainty. If nothing is certain, empiricism is a lie, and only my truth is evident. There are some people who take that route. I think some of the anti-vaccinationists are members of this camp.

Or we can decide that certainty in knowledge is unreachable – but that uncertainty leaves space for much of what makes healthcare deliverable to people, and not to subjects of experiments or inanimate objects. It leaves room for our preferences in the face of the unknowable.

I don’t know if that is enough to cut doctors slack for what can’t be known, but maybe it can help us feel less at sea in the realm of scientific uncertainty – which is the universe, really.