Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 17

November 10, 2013

A built-in second opinion?

It was my turn this weekend to cover for my colleagues in our internal medicine practice. It wasn’t all that strenuous. One of the hardest things to do, however, is justify to a patient a decision that another doctor has made that I might not agree with. It is hard to reconcile the many contradictions inherent in such a disagreement. On the one hand, the knowledge that medicine involves a spectrum of truths; on the other, the conviction that many courses of action taken for granted in today’s practice are mistaken – overuse of tests and procedures among the most common of them. There is the relationship between the patient and their primary care doctor which one is loath to interfere with, and then there is the need of the particular person at that time. Finally, there is the fact I referred to above: we are all in a practice, and so – to a greater or lesser extent – we share patients. Sometimes, it’s a good thing for our care to be viewed by a different pair of eyes and addressed by a new set of assumptions. Isn’t that what quality care is meant to be, if we agree with the assumption that it is quantifiable – an opportunity for someone to evaluate care at a clarifying distance?

Whenever a colleague of mine sees my patients, I hope they might see something I have not noticed before. Maybe every person who sees a doctor should be granted that opportunity with regularity: a built-in second opinion to make sure opportunities and dangers aren’t missed.

November 6, 2013

Why she had her stroke

The note said she was non-compliant with her medications and that’s why she ended up in the intensive care unit. But she came to her appointments with me every month, as regular as a sunny day in June (or, given her uncontrolled depression, as predictable as a rainy day in London). She couldn’t take her medications, no matter how convenient it would be to pin the non-compliant label on her.

Money was always tight. Her family stole from her time and again. She barely had enough for rent. As depressed as she was, she wasn’t sure sometimes that doctors or hospitals had anything to offer at all – maybe they were experimenting on her. (After all, they have been experimenting on people for generations, sometimes people that look much like her.)

To call her non-compliant is a peculiarly cruel bit of note lingo. If anything, the system was non-compliant: not pliant at all, but brittle like a piece of untempered glass, and jagged, drawing blood.

November 4, 2013

Meeting illness in stages

Posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

I saw a friend and colleague today, a physician, who is back from maternity leave, her child finally out of the NICU and mercifully healthy. She had the unwanted chance to see some of the health care system from the caregiver’s side, and the glimpse wasn’t all heartening. “It’s true what they say,” she remarked. “It’s different to see things as a patient.”

I haven’t seen the health system much from the other side. We have had our children, but my wife was the one who assessed the quality of the obstetricians and gynecologists first-hand. I have taken these children to the doctor, but not for anything serious, thank goodness. We are healthy and my parents are well.

But time will pass, and people will age and fall ill. That is nothing to look forward to. Each experience, however, will shed a different light on what it means to be a patient – and perhaps, in so doing, these experiences will make me a better physician, or at any rate a more sympathetic human being.

By the same token, as you – whoever you are, whatever situation you find yourself in – make your way through the many small fears, midsized setbacks, and destabilizing tragedies that make up much of life, you will become more experienced in knowing how you and your family react to them. You can help your doctor understand what sort of a person you are when such difficulties hit, and continue to invest in a relationship that might help in these circumstances.

October 30, 2013

Pointing fingers at dishonest doctors…and at ourselves

I was shocked to read about what some doctors at my institution have been doing. Read the whole article, which is thoroughly researched, painstaking, and – not to mince words – damning. A group of radiologists, with a distinguished senior scholar at the head, have been interpreting X-rays and CT scans against medical and scientific consensus, sacrificing not just intellectual consistency but the fortunes of coal miners and other workers, whose diagnoses of black lung were thrown into shadow, and whose legal suits found in favor of their employers.

We can point fingers at these doctors. If I didn’t work at Hopkins, perhaps I would go on at greater length here about what their systematic deviation from scientific practice means for patients’ lives.

The more you think about it, though, the more you realize that we are all implicated, in greater or lesser measure, in similar activities. Our motives are perhaps not as venal; the connection to coal company’s payment not as relevant. But inconsistency of diagnostic practice, dealing out judgments, interpretations, and prescriptions not based on the best scientific evidence, and depending on pseudoscientific “lore” under the influence of economic factors are all widespread in today’s medicine.

In fact, if you consider how widespread in today’s medicine is the use of non-evidence-based treatment, you understand that this pneumoconiosis story is only the tip of a very black iceberg indeed.

October 24, 2013

Notes from Baltimore: telling patients’ stories without divulging their secrets

Cross-posted from the LitMore blog. Thanks to Julie Fisher for the opportunity!

In the first months after I got here, I asked myself when I would be able to say “I come from Baltimore.” Then I realized that’s a stupid question. A city doesn’t require the participation of any given person. That is its promise of freedom and alienation: you can move to a city and be completely anonymous. Baltimore doesn’t care whether I’m from it or not.

The real question is: have I really gotten to know Baltimore yet? Do I feel a part? Living here means confronting huge daily diifferences. Black and white, rich and poor live starkly opposed lives in this city, and since I have always lived a life of comparative privilege it becomes a responsibility to place myself, somehow, within the entire city of Baltimore, not just the thin strip of rich white suburbs I live and commute in.

It’s hard to meet different kinds of people. You have to talk to strangers, which I’m not comfortable doing. But there are two things I love which have helped me overcome, if only in small measure, my city-dweller’s inertia which keeps me an individual in an atomized society. One is writing. The other is medicine. The two – especially in Baltimore – reinforce each other.

I work as a doctor in the gleaming city on a hill that is the Johns Hopkins medical campus. Hopkins has had its difficulties relating to the community, and only in past decades come to realize its responsibility and interrelatedness with it. I practice general internal medicine: in other words, I treat sick and healthy adults of all sorts: all colors, sizes, ages, shapes, and incomes.

As an ordinary person, I am impatient, preferring the constrained dimensions of poetry to the sprawling indulgence of a novel. “Yeah, get to the point,” I tend to mutter to myself when someone treats me to a tale. As a doctor, not through any alchemy but by dint of education, sustained practice, and proffesional aspirations, I listen more. I take down stories. I write down patients’ tales of suffering, anguish, success, heartbreak, and courage nearly every day – without any attention to literary artifice or style.

Unfortunately, I can’t tell these stories to anybody. This is a good thing, I think, this confidentiality. But it does compartmentalize. Over here is my comfortable, privileged rich-white existence, the one lived by 25% of Baltimoreans, more or less. And over there is the existence of many more Baltimoreans who are different from me in various ways. I can’t tell their stories in all their painful exactitude outside of work. Recently, many medical centers have started “allowing” patients to see their own medical notes, but none in Baltimore that I know of – and at Hopkins that is definitely not the case.

What I can do, though, is make up stories about people like them that I can share with the wider public, or at least with whoever wants to read them. Thus, without any concrete plan in this regard, I have been trying to write short stories ever since I came to Baltimore. I’m just starting out so I’m not very good at it. Learning how to put characters through their paces feels a lot like learning the lessons I have perhaps more completely internalized, in the past decade or so, as a parent of young kids: you can try to bodily move them from place to place, strenuously indicating that they should PUT ON THEIR SHOES and GET INTO THE CAR, but sometimes characters – like kids – have to be let alone to do what they want.

These stories that I’m trying to write and the narratives I record in the medical chart have a lot in common. They are meant to be read. They have a point: In the medical record, Chekhov’s adage about the gun hanging on the wall is all the more fitting. If someone comes to the doctor with chest pain, the doctor better proffer an explanation, by the end of the note, why she thinks the pain is there. Medical notes, like stories, can’t be loose, baggy, or meandering. They must hold the reader.

And both the medical note and the created story must understand the other human being, through acknowledging their concrete yet unknowable specificity. As a doctor I might not know what it is like to have many relatives in jail, others with mental illness, and still others with substance use problems. But I know what pain is like. When a patient comes to me with pain, I can try and heal it despite my ignorance of their inner life.

As a writer, I can no more divine someone’s psychic struggles than I can as a doctor. But I can try and externalize those struggles in a plausible way through showing what they do, what happens to them, what they say and how they react. I don’t aspire to any measure of healing through my still-inexpert prose stylings. But I do hope to inhabit this city of inequities more fully, and become another in the long line of Baltimore writers: if not through my stories, then at least through my medical notes in the privacy of the exam room.

Super Jewish Historical Prediction Game: Delegitimization Edition

It’s been a while since we played this game. But it never goes out of style!

1990

Cathy Conservative: Gee, these Israeli rabbis don’t recognize my ordination!

Joe M.O.: Pshaw!

2013

Joe M.O.: Gee, these Israeli rabbis don’t recognize my ordination!

Cathy Conservative: [fill in the blank]

October 23, 2013

What do you wish you had known? And how will you change?

Cross-posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

I am always interested in asking, “What questions should you have asked before….” And with the ellipsis I am talking about any health care situation. What questions should you have asked before you picked a doctor? chose a treatment? heard about your diagnosis? filled your prescription? discussed end-of-life care with your family member?

So what should you have known? What could you have done differently in the process of making decisions, advising, treating yourself or others, or just coping?

And, to take it a step farther, now that you have thought about what you should have asked differently, will that change what you do in the future? How are you going to make that change happen?

October 21, 2013

Getting from a doctor-centered system to patient-centered care

Here is a talk I gave at the annual meeting of the National Physicians Alliance on October 20, 2013, in Washington, DC. The briefest version is this: Everyone talks about patient-centered care and realizes that our system is doctor-centered. How do we square the circle and get from one to the other? Patient-centered care is a mantra more often repeated than deliberated on and well defined. We must recognize that patients are unique individuals, and that the relationship between the primary care provider and the patient, a pillar of an improved system, must include all sorts of patients – no matter what their desired involvement in decision-making.

October 18, 2013

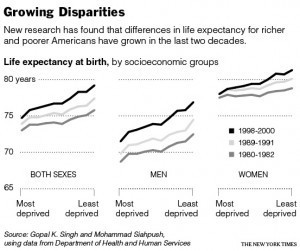

Voyaging through health inequality

Cross-posted to the blog.

I’m going on some smaller and longer trips over the next weeks, which put the topic of health disparities in comparative contexts. Disparities is the scientific term for health inequities. In short: everyone should get the same healthcare, but not everyone does. You get worse care if you’re black, or poor (unfortunately, those are obvious). What about if you are older, or LGBT, or speak a language other than English, or live in a rural area, or have a chronic illness, a disability, or a mental health issue? Probably. But the question is not just yes or no, obviously, but how, why, and what the solutions are.

Next Friday, October 24th, is the most local of the events. I’ll be giving a 400-second talk, that’s 20 slides in 20 seconds each, at PechaKucha Baltimore, the first local rendering of the speedy-talk format that has already been done in a number of other cities. My topic will be Talking Heals. And, while I won’t be mentioning specific health statistics about Baltimore inequalities (400 seconds isn’t enough for statistics!) I will certainly have in mind the great, abiding fact of Baltimore life. “The rich are different from you and me,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald said in another context: yes, they have more money (as Hemingway is supposed to have responded), and thus more health. How can we bridge the gap? Part is access (the poor in Baltimore can’t get in to see doctors, there’s a shortage of internists), part is cost (for obvious reasons) – but part is also quality. And part of that quality piece is to make sure that doctors and patients can communicate across lines of race, class, and origin.

On the preceding Sunday (I’m discussing these events out of their chronological order), October 20th, I’m giving a talk at the National Physicians Alliance: how do we make our doctor-centered system into patient-centered care? You might not be surprised to hear that the solution I proffer is neither all one thing (patient centrism, the advice of the doctor be damned!) nor all the other (status quo and to heck with EMRs!) but something in between: investing in and maintaining relationships.

Finally, in December, I am heading to Peking Union Medical College Hospital in Beijing, at their kind invitation. I hope to acquaint myself with their system and China’s system at large, which I am sure demonstrates some inequities unique to the Middle Kingdom and some shared with the US as well. From what little I know about the current Chinese socioeconomic climate, there is rapid and thoroughgoing social change – which I hope has not swallowed up previous governmental plans to provide better primary care access to millions of Chinese.

Through these multiple dimensions of care, quality, and access, applied across various regions, we can aspire to great change. Lots to do!