Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 16

December 23, 2013

On first meeting someone: preliminary reflections on the Chinese health care system (final installment)

A country is like a person. Initial impressions matter, but if you really want to know them, you have to spend more time.

The Chinese health care system has many problems in common with the US: inequalities, lack of access, and widespread corruption due to the profit motives of pharmaceutical companies. Both systems are afflicted by overuse of services without clear health improvement. In the US, doctors get paid more if they order more tests; and in China, doctors’ salaries often do not meet their cost of living, while they are allowed to make direct profits on pharmaceuticals and tests: the resulting incentive is clear.

But generalizations don’t go very far in the hugeness of China. Beijing has 18 million residents or so, but Shanghai is China’s largest city, and its health care system is significantly different from Beijing’s, thanks to the reforming efforts of its vice-mayor who is implementing the Chinese equivalent of accountable care organizations, reforming residency education, promoting family practitioners as the integrators and gatekeepers for health services, and pushing through vertical and horizontal EMR integration. (The article from which I gleaned this information is based on an interview with this very vice-mayor, so the successes should probably be taken with a grain of salt.)

In the cities, where two-thirds of Chinese now live, public hospitals deliver the vast majority of health care services (accounting for 65% of health care costs nationally), but do so inefficiently and ineffectively, and are thus a chief target of governmental efforts at reform.

Out in the villages, where significant numbers of Chinese still live, the situation is very different from these big cities: access to care is dismal and quality a big question mark.

For now, I am grateful to have come to China not just as a tourist, but to learn something, share some of my knowledge with my hosts at PUMCH, and hopefully to start up some substantive collaboration.

Thanks to Dr. Jun Zeng and the entire GIM division at PUMCH. Thanks also to Junya Zhu of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health for a crash course in the Chinese health system.

December 14, 2013

כינע און אַמעריקע: צװײ געזונט-סיסטעמען אױף צרות

אַ טײל מענטשן זאָגן, אַז כינע װעט באַלד פֿאַרשטעקן די פֿאַראײניקטע שטאַטן אין גאַרטל אַרײַן. אַ מעכטיקער כּוח אױף דער װעלטבינע, האָט כינע עטלעכע מקורים פֿון קאַפּיטאַל: די ריזיקע באַפֿעלקערונג, דער אינטעלעקטועלער דינאַמיזם, און דער עקאָנאָמישער װוּקס, וואָס אַלע שטעלן זיי מיט זיך פֿאָר בלױז עטלעכע פֿון די מעלות, װאָס זײַנען אפֿשר שױן באַקאַנט אַ צאָל „פֿאָרװערטס‟-לײענער צוליב די װידעאָ־רעפּאָרטאַזשן פֿון שמואל פּערלין.

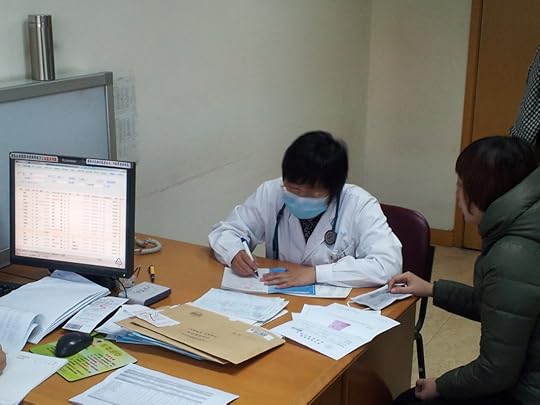

א דאקטער זעט א פאציענט אין א ביידזשינגער קליניק פון אינטערנאלער מעדיצין.

ניט געקוקט אױף די ריזיקע מעלות, שטײט אָבער כינע אױך פֿאַר גרויסע שװעריקײטן, װאָס זי האָט, אין טײל פֿאַלן, בשותּפֿות מיט אַמעריקע. װי אַ דאָקטער, געקומען קײן בײדזשינג, צו פֿאַרברענגען אַ װאָך צײַט און האַלטן רעפֿעראַטן פֿאַר אינטערניסטן אין איינעם פֿון די פּרעסטיזשפֿולסטע שפּיטאָלן, געפֿין איך זיך אין אַ פּאָזיציע, וואָס גיט מיר די מעגלעכקייט אָפּצושאַצן די געזונט־סיסטעם פֿונעם לאַנד. אמת, אַז כינע קען שטאָלצירן, טײלווײַז, מיטן זעלבן ניװאָ פֿון טעכנישער פֿעיִקײט װי אין אַנדערע רײַכע לענדער. פֿאַראַן די זעלבע פֿאַרצװײַגטע נעץ לערן־אַנשטאַלטן, פֿאָרש-אינסטיטוציעס, און שפּיטעלער, װי בײַ אונדז אין די פֿאַראײניקטע שטאַטן. דאָרט, װוּהין איך פֿאָר הײַנט, געפֿינט זיך אײנער פֿון די רײַכסטע שפּיטעלער אין גאַנצן לאַנד. אַז מע װערט דאָרט אַרײַנגענומען צו לערנען זיך אױף דאָקטער, איז עס אַ סימן, אַז מע װעט װערן מיט דער צײַט אַ גוט-באַצאָלטער ספּעציאַליסט.

די כינעזער שטײען אָבער פֿאַר דער זעלבער פּראָבלעם װי די אַמעריקאַנער. בשעת די טעכניק און די פֿעיִקײטן שטײַגן, און די װיסנשאַפֿטלעכע חידושים מערן זיך, װי שװאָמען נאָך אַ רעגן, איז אַלץ ניט קלאָר, צי די װיסנשאַפֿט און די באַהאַנדלונג פֿון פּאַציענטן פּאָרן זיך אַזױ גוט, װי מע האָט געמײנט. בעסער געזאָגט, עס װערט אַלץ מער בולט, אַז ניט. אין אַמעריקע, טאַקע צוליב אַזעלכע װילד-שטײַגנדיקע הוצאות, און דעם נאָגנדיקן געפֿיל, אַז עפּעס איז ניט פֿױגלדיק מיט דער געזונט־סיסטעם, װערן הײַנט אײַנגעפֿירט, ניט אָן גרינע װערעם, ריזיקע ענדערונגען אין דער דאָזיקער געזונט-סיסטעם.

אינטערעסאַנט איז, אַז כינע האָט ענלעכע פּראָבלעמען. די צאָל אָרעמע-לײַט איז במילא אַלע מאָל אַ ריזיקע, צוליב דער קאָלאָסאַלער באַפֿעלקערונג; און די נאַציאָנאַלע רעגירונג זעט שױן אײַן, אַז די אָרעמע-לײַט װערן ניט גלײַך באַדינט פֿון דער געזונט-סיסטעם. מיט אַ פֿופֿצן יאָר צוריק, האָט כינע אײַנגעפֿירט אַ קאַמפּאַניע צו דערמוטיקן מעדיצין-סטודענטן, זײ זאָלן װערן אַלגעמײנע דאָקטױרים. נאָר די איניציאַטיװן זײַנען אַראַנזשירט פּונקט אַזױ קרום װי אין אַמעריקע: לטובֿת די טײַערע ספּעציאַליסטן, ניט די פּראָסטע דאָקטױרים. עס גײט אױך אין דעם, לױט דעם מעדיצין-סטודענט װאָס באַגלײט מיך דאָ, אַז כינע גיט אױס נאָר איין פּראָצענט פֿון אירע נאַציאָנאַלע הוצאות אױף געזונט; און די געזונט-מיניסטאָרשע איז די סאַמע מאַכטלאָזסטע צװישן אַלע 28 מיניסטאָרן אינעם פּרעמיער־קאַבינעט.

די אומגלײַכקײטן אין כינע און אין די פֿאַראײניקטע שטאַטן זײַנען געקומען צו שטאַנד צוליב פֿאַרשידענע סיבות. כינע איז פֿון קדמונים אָן אַ לאַנד פֿון אומגלײַכקײט, צוליב די מאַסן פּױערים אין דאָרף און דער גבֿירישער אַריסטאָקראַטיע אין די שטעט. אַמעריקע איז אַנדערש: כאָטש װײניקער מענטשן זײַנען שטאַרק אָרעם װי אין די פֿריִערדיקע דורות, װערט די אומגלײַכקײט צװישן אָרעם און רײַך אַלץ שטאַרקער. נאָך דער צװײטער װעלט־מלחמה, האָט די מעדיצין זיך אַלץ מער קאָנצענטרירט אױפֿן אַקס פֿון װיסנשאַפֿט, לאַבאָראַטאָריע-פֿאָרשונג, און אַקאַדעמישע אַנשטאַלטן, און אַלץ װײניקער — אױף טאָג־טעגלעכער דאָקטערײַ. װי איך האָב שוין דערמאָנט אין אַ פֿריִערדיקן אַרטיקל מיט אַ געזונט-עקאָנאָמיסט, גיבן מיר אױס מער און באַקומען װײניקער; מיר װערן ניט געזינטער, ניט געקוקט אױף די גרױסע געלטער, װאָס אונדזער סיסטעם צעטרענצלט.

די רעזולטאַטן זײַנען ענלעך אין בײדע לענדער: די פּאַציענטן װײַזן אָן, אין די אױספֿרעגן, װײניקער צוטרױ צו זײערע דאָקטױרים. די ספּעציפֿישע באַריערן צװישן חולה און געזונט-אַרבעטער זײַנען מן-הסתּם אַנדערש: ראַסן-אומגלײַכקײטן זײַנען געקניפּט און געבונדן מיט די געזונט-חסרונות פֿון אַמעריקע, בשעת דער ריס צװישן שטאָט און דאָרף וואַרפט זיך אין די אויגן מער אין כינע. די געפֿאַר אין בײדע פּלעצער איז ניט אַװעקצומאַכן מיט דער האַנט. אין כינע זײַנען לעצטנס אױסגעבראָכן מהומות אין אַ פּראָװינץ־שטאָט, װוּ אַ דאָקטער איז דערשטאָכן געװאָרן אױף טױט, צוליב אַן אומצופֿרידענעם פּאַציענט. דאָס האָט אַרױסגערופֿן שטורמישע דעמאָנסטראַציעס מצד די געזונט-אַרבעטער, װאָס האָבן מורא פֿאַר זײער לעבן.

כאָטש די אומרויִקײטן אין אַמעריקע זײַנען שטילער און מער געזעלשאַפֿטלעך װי רציחהדיק, איז די געפֿאַר בפֿירוש ניט קלענער. צוליב דעם האָבן פֿאָרשער אין די פֿאַרגאַנגענע יאָרצענדליקער זיך גענומען צו דער פּראָבלעם פֿון דער דאָקטאָר-פּאַציענט באַציִונג, און װי אַזױ מע קען זי פֿאַרבעסערן; דערמיט, אפֿשר, צו פֿאַרבעסערן דאָס געזונט און אַלע שיכטן אין לאַנד. אין כינע ווײַזט מען אויך אַרויס אַן אינטערעס צו אַזאַ פֿאָרשונג, װי אױך אין שאַפֿן אַלגעמײנע דאָקטױרים, װאָס זאָלן אָנריכטן די מעדיצין, פֿון דאָס נײַ, אױף די אינטערעסן פֿונעם פּאַציענט.

איך קוק אַרױס זיך צו באַקענען מיט מײַנע כינעזישע קאָלעגעס, און הערן בײַ זײ װאָס זײ טוען, כּדי מער כינעזער זאָלן געניסן פֿון געזונט, גליק און אַריכות-ימים.

December 12, 2013

Know yuan to say yuan: report from Beijing on quality, patients, and doctors

[Pictures at the book blog.]

On this third full day as a guest in Beijing of the General Internal Medicine department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, or PUMCH, I had an enlightening chat with the medical student I have mentioned in previous posts.

We were walking towards an outpatient GIM clinic down a corridor choked with people; these clinics are overbooked because of PUMCH’s reputation (I’m not sure if there is a doctor shortage in China generally). I asked how much it cost to see a doctor in this clinic. “7 yuan,” he said. I kept going. How much does a CT cost? An MRI? A knee replacement? He gave specific costs without hesitation. “How much does a CT cost in the US?” he asked.

I laughed. We both knew the question is ridiculous. Transparency in cost and quality is a dream for the US system given the extent of variation in health care use and that hospitals can charge whatever they damn well please.

It was appropriate, then, that I gave a talk today at PUMCH on public reporting: that is, information provided by various entities on cost and quality in the US, and whether this information actually changes decision making, patient satisfaction, or outcomes. An article we published on the topic is here.

The audience included not just doctors, residents, and medical students, but members of the medical affairs staff and those concerned with hospital quality at PUMCH. It appears there is not much research literature addressing how patients pick their doctors in China. Given the completely out-of-pocket nature of much of Chinese health care, however, it could be that greater price and quality transparency is possible in the Chinese system than in the American. To take one example, on-line doctor ratings in China appear to be widely used and, as I was told at any rate, influential.

The high point of today, however, was observing in the outpatient clinic of Dr. Jun Zeng, the head of GIM at PUMCH and, in addition to being an internist, a rheumatologist. From a diagnostic and treatment perspective, I saw that she used corticosteroids in many cases where her American counterparts in rheumatology would use the increasingly popular, and expensive, TNF inhibitors. I asked her about this and she said proudly, “I’ve been practing for 20 years and know how to use these mdications in a stepwise fashion – steroids work in many cases, and TNF inihibitors are not always needed.”

I loved to see how she sat a table face to face with a patient, writing in a notebook while her junior colleagues provided prescriptions to the patient she had just seen. “What’s the matter?” she started off a visit, and another – “What can I do for you?” Great openings. I couldn’t understand all the Chinese, but I could see someone who was doing her utmost to provide patient-centered care given the limitations of her system – which, come to think of it, I need to ask them explicitly about: what frustrates them about Chinese medicine in the same way that my frustrations typify American medicine?

December 10, 2013

Poems of heresy and transformation: a review of Prayers of a Heretic by Yermiyahu Ahron Taub

If poetry requires disclosure, I’ll start with one: I am a friend of Yermiyahu Ahron Taub’s, and a fellow Yiddish poet. He sent me his book with a kind dedication, and an additional inscription in his neat hand: bet-samekh-daled. That is, the author of this book entitled “Prayers of a Heretic” noted that his signature to me was written “besiyata-dishmaya,” with the aid of Heaven.

Such a juxtaposition is an illuminating introduction to the contradictions in Taub’s work. He left the ultra-Orthodox community, but that is not the subject of his poems any more than sex is the topic of Yona Wallach’s — that departure makes the poems possible, but the volume is not merely a translation of his personal story into poetic biography. Rather, this transformation gave him a set of tools. To become someone else is a lasting condition of every living person; Taub’s particular experience of that change makes him able to perceive it in others.

Read more in the Forward.

First full day in China

I am exhausted, but before I drift off to bed here in Beijing I wanted to give an account of my first full day.

I sat in on rounds at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, my host and one of the top-ranked hospitals in China. The General Internal Medicine Division is renowned for its ability to treat the hardest cases and consistent high reputation, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy in certain respects (sound familiar?).

The similarities are not all that interesting: the team sits round a table and talks about the new patients, then walks through the wards seeing the old patients. Questions are asked to put medical students on the spot (in American English we have a word for that). The differences, however, are somewhat instructive.

In the United States, at least in the internal medicine programs I am familiar with, the senior resident runs rounds and the attending stands by the side to give a teaching point or a minor correction; here, it was the attending leading the discussion. In the United States, the entire team, in many hospitals, is by now acculturated to use hand sanitizer on leaving and entering every room. In the PUMC GIM ward, I was told by someone that I didn’t need to use sanitizer if I wasn’t touching the patient.

There was one similarity which was immediately evident: the hierarchy that hung over interactions between doctor and patient, and the great respect with which the patients treated the doctors every word (though the medical students I spoke to later expressed worries that patients no longer respected them). I don’t understand enough Chinese to know whether the doctors were attuned to the patients’ needs apart from their own particular workflow needs on rounds, but if these doctors are anything like many American ones, I can guess the answer…

* * *

Later, I had the great opportunity to give a presentation for medical students about bridging evidence-based medicine and patient-centered care, using localized prostate cancer as a case in point. We are trying to understand why patients with that most limited stage of cancer might leave an active surveillance (watchful waiting) program to get radiation and surgery which might not be clinically indicated.

We had a lively discussion. I fielded an expected question about what differences I noticed between the Chinese and American health care systems, after less than 48 hours of superficial experience with the former. I tried to demure, but one thing I did talk about was the overuse in the American system, over against the underuse in China which is prevalent for millions and millions of mostly rural poor. We also talked about what doctors might do when what patients want is against the best evidence.

After the lecture, I had a chat with a student of Uygur ancestry who was very interested in the role of religion in health care in the United States. I told him what I think is true: aside from end-of-life care and bioethics, the role of religion is underexamined.

* * *

Finally, I met a bioethicist, Yali Cong, from the Peking University Health Science Center (not to be confused with PUMCH, above. A city of 20 million, Beijing has a lot of hospitals!). We talked about one of the chief difficulties for those involved with clinical and research bioethics: the expectations of clinicians that bioethics will be able to give an “answer,” where in reality what a bioethicist can give is an overview of possibilities, a mapping of the territory, and – in the most lasting influence – a habit of thought that even, or especially, non-bioethicists might benefit from.

* * *

It’s been a great visit so far, and even after I leave China I hope to connect with people here through email and Weibo, my newest social media addiction made all the more interesting by the fact that my Chinese is a lot less than fluent.

December 9, 2013

Getting out of the dark wood: a 400-second presentation on communication and health

PechaKucha is a presentation format in which the speaker tells their story in “less is more” fashion, using only 20 images and speaking for only 20×20 seconds. Thanks to Hillel Glazer and some other high-energy organizers, an evening of such presentations recently took place in Baltimore. Check out mine below, featuring Dante, the caduceus, and communication.

December 8, 2013

Voyaging to China: or, Dr. Google, meet Professor Wittgenstein

This week I will be giving a series of talks at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, and even more important, learning how internists in that institution see their route to bridging patient-centered care and medicine’s evidence base. I hope to write about my visit daily, if not necessarily to post (that depends on internet connections and whether I can reach social media). Photos will come later.

It’s also an excuse to improve my execrable Mandarin. I know it is bad, despite the unfailing support and friendliness with which many Chinese greet my halting attempts at the language.

I love learning languages, though my success has been varied. I am old enough to remember what it was like to learn a language before Google Translate. An estimable tool, to be sure, one that facilitates looking up those fiendish arthropodian characters with 15 strokes.

Yet we all know Google Translate has problems. Sometimes, with all its fantastic power to make an educated, database-driven guess as to what the source text must mean, the translations stink. No human being fuent in that language would produce such a sentence.

Which is why Google Translate still needs supplementation by dictionaries. Of course, today’s dictionaries use much the same technology as GTrans: databases, search strategies. But they are curated, assembled by teams of lexicographers who are able to bridge the native expressions of one idiom with those of another.

I never shy away from analogizing, and you might have guessed where I am going with this.

Evidence-based medicine produces a number of studies. The best guidelines generate recommendations based on large datasets requiring considerable computational power, in order to model the interaction between various variables and the outcome of interest.

Yet we doctors and patients know that sometimes these guidelines, even those produced by the best science, come out with suggestions that bear faint resemblance to the options available to real human beings living complicated lives – the same way that the frictionless surface beloved of physicists is a crude approximation of sublunar life.

By now it is a cliché to say that the art of medicine is a language in itself. That’s not quite what I am saying here. Only patients are fluent in their own languages: idioms of body, society, family, daily life. Together, providers and patients can function as an expert lexicographic team, bridging the ever-improving, but still sometimes outlandish recommendations of Google Medicine, with the diverse speech of real human beings.

Dr. Google, meet Professor Wittgenstein.

December 2, 2013

The Adequacy League

I haven’t written much about parenting, because most of it is hard and boring. Like maintaining health, either as a doctor or a patient, it’s usually a slog, requiring wellsprings of confidence to remain sure that what one is doing in the moment will have some measurable impact down the line. To that end, I have decided to found an organization to inspire such confidence, while establishing standards that can make most of us – the average parents, the pretty-good providers – feel supported in the slog. It is called the Adequacy League, and will have at least two arms, one for parents, one for physicians and patients.

The League of Adequate Parenting will emphasize that most of us who bellyache about child-rearing, and fear that we are not doing well enough, are actually doing just fine given our circumstances. This means, of course, that if we are parenting in resource-rich circumstances, we should appreciate that fact: our adequacy is not likely to be the same as that achievable under other circumstances.

Similarly, the Adequate Doctors-and-Patients’ Union recognizes – by charter! – that there is a tension to medicine. On the one hand, much of what ails us gets better with time, and we ought not to interfere with that. But, on the other hand, we want to actively interfere in a great many conditions for which there is no “natural” cure. Adequacy means neither interfering without exception on principle nor refusing to intervene on the basis of some misguided alliance with “nature.” Neither doing too much nor too little, and not looking over one’s shoulder continuously at the latest study. The adequate doctor or patient can be satisfied with her efforts toward health even as she knows she is not perfect.

Adequacy does not mean complacency, but the ability to take stock of our current limitations, appreciating all we are managing to do.

Excellence can be quantified, sure, and we should all aspire to it. Poor performance can be avoided as well with the help of keen analysis. But neither striving for excellence nor avoiding error and harm can get us through a weekday morning, a whiny toddler, a chronic illness, a day full of things-to-do and people with quite legitimate demands whom we need to serve. Sustaining a notion of adequacy is key. The Adequacy League recognizes this. Though it presents no awards, reimburses no one for travel expenses, and has no meetings, it will exist, quietly, wherever you are, as long as you need it.

November 25, 2013

Trash-talking other doctors?

A recent research article in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, and the gap between its findings and the real world, helps point up the usefulness and limitations of research. The article, by Susan H. McDaniel, PhD, and coauthors, set out to determine how often doctors speak about their colleagues in supportive or critical ways.

Their method is one widely used in the field: simulated patients, actors, were prepared with lifelike stories about their feigned cases of advanced lung cancer complete with manufactured charts describing what previous doctors had done. The conversations they had with physicians (some oncologists, others family medicine practitioners) were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed; each statement by a physician about the care provided by other doctors was categorized as Supportive, Critical, or Neutral.

The results were not altogether surprising, but I’ll let their abstract’s summary speak for itself (I edited it slightly):

Twelve of 42 comments (29 %) were Supportive, twenty-eight (67 %) as Critical, and two (4 %) as Neutral. Supportive comments attributed positive qualities to another physician or their care. Critical comments included one specialty criticizing another and general lack of trust in physicians.

As far as I can figure out, however, the article did not discuss what doctors should do in a very common circumstance: when their patients did receive treatment from another physician that they, the doctors, feel was incorrect. Last week, for example, I saw a patient who had been treated by some oncologists (they weren’t from Hopkins – which doesn’t mean this story couldn’t have applied to them). They had given her treatment without discussing with her the risks or benefits. She came to me bewildered and frustrated.

So what should I have done in that case? Made polite noises? Reflected the patient’s feelings? I did those as well. At some point, though, the patient’s intuitions should be verified and the truth called out: no, it is not okay to leave the patient’s wishes and preferences out of the equation, and all the more so when they are vulnerable, as cancer can make anyone.

Sure, tactfulness is key, and collegial relations with other providers can be maintained in such a circumstance, but identification of systematic missteps in care (such as leaving the patient out of a treatment discussion) is no vice. In fact, such honest talk is in the very service of professionalism.

How do you talk about your other doctors with your primary care provider?

November 18, 2013

How you can talk to your doctor about cholesterol

I’m not going to discuss the entire subject of cholesterol in this post, but one part of it: specifically, how to discuss with your doctor how much cholesterol should matter to you.

If you have read any health news in the past week, you know that the American College of Cardiology and the American Health Association issued new guidelines to help doctors advise patients about cholesterol medications. The new recommendations are accompanied by a calculator of heart risk into which one enters various laboratory and personal characteristics – whether you smoke, have diabetes, have high blood pressure, and the like. Unfortunately, a kerfluffle has ensued over some errors present in the calculator. Millions of Americans, under the new guidelines, might be recommended to receive cholesterol medications – and this massive expansion of the medicated populace is under dispute.

Putting that aside, however, we will focus here on an even more basic question: how do you know what level of heart risk is important to you? Any recommendations about whether or not to use a cholesterol medication – the old ones and the new ones – depend on the application of calculation to you: the doctor will calculate the risk in the next 10 years that you will have a heart attack, and use that number to decide whether you should be taking a cholesterol medication.

However, that assumption crumbles the harder you press on it. First you should discuss with your doctor whether you are in one of the high-risk categories which places you at significant risk of heart disease in the first place: a family history of early heart disease or stroke; or a history of diabetes in yourself. Perhaps, on the other hand, you are generally healthy and your risk of heart disease is low – this is probably most people. A significant proportion will fall somewhere in the middle.

But even if your risk lies at one of these two extremes, and your doctor is confident in telling you that your risk of heart disease is high (or low), there is one essential point to keep in mind which is underemphasized in all the media coverage of the new cholesterol guidelines:

Whether to take such a medication is still, and always, your decision.

This is not “your decision” in the sense of: go play in traffic, see if I care. Rather, your decision-making must take into account a whole variety of factors, which can be clarified by thinking about the following questions, or discussing them with your doctor:

Cholesterol medications can reduce the rate of heart disease, but there’s a difference between absolute rate reduction and relative rate reduction. If a cholesterol medicine reduces your rate of heart disease by 50%, that sounds great, but it’s less impressive if your 10-year chance of developing heart disease was only 5% to start with. Maybe you can live with a 10-year chance of developing heart disease that’s 5 in 100. So you might ask: “What is my baseline risk of developing heart disease, without a cholesterol medication?”

Cholesterol medications can cause side effects not uncommonly. Some studies cite a rate of 10% for the rate of muscle-related symptoms (this is probably the upper range of the rate, including everything from muscle aches all the way to significant muscle inflammation). You are really the only one who can weigh the chance of side effects to the benefits of the medication. But you might ask, “How would you compare the risks and benefits of this cholesterol medication?”

Finally, it’s important to realize the imperfect nature of all guidelines. A guideline is merely a compendium of recommendations, and a recommendation can only be useful and relevant to you if two things are true: (a) it is based on good scientific evidence; (b) this evidence is relevant to your particular needs, sensitivities, and circumstances. About (a), you should ask your doctor, “How confident are you in the scientific evidence that backs up this recommendation?” Pay particular attention, for example, to how they understand the balance between risks and benefits in the subpopulation (i.e. the risk category) you fall into.

With regard to (b), of course, you are the only one who can make that determination, and no guideline can substitute for your considered, informed decision.

Image courtesy of the Mayo Clinic.