Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 22

August 2, 2013

What should you look for when picking a doctor?

Thanks to Mike Benedetti and Happiness Pony for printing this piece in their latest issue (found in your favorite Worcester, Mass., coffee shop. This is also cross-posted to the book blog.

Picking a doctor is not like choosing an ice cream flavor. But it’s not like betting on a sports game either. When we set about choosing a physician (or whoever else, nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant, who might act as our primary care provider), our personal preferences certainly come into play. We might want as our doctor a man or a woman, someone convenient by bus, someone younger or older. Some people, like it or not, prefer their doctor to be of a certain race – just like doctors treat their patients differently based on race. This is of course not my ideal but the fact of the matter. Even if we only have a limited choice of doctors covered by insurance, we might pick between the two or three available based solely on whim.

But what if we wanted to pick the best doctor available, the professional who is most likely to make us feel better? There is a plethora of information available online that purports to answer that question, from a simple Google of the doctor’s name to a search in Physician Compare (the national database of doctors that accept Medicare), to records of physicians’ prescription practices. Unfortunately, there is no foolproof way to link up this dense network of statistics to the results that actually matter to us: our health, happiness, satisfaction, and emotional needs, all of which we would like to see satisfied when we see our new doctor. There is no magic formula to predict which doctor is most likely to work well with you, the acolytes of Big Data and electronic medicine notwithstanding.

That is why choosing a doctor isn’t like placing a bet: we might not be sure if we made the right choice even when we meet them for the first time. As in other relationships, the connection with our doctor (or nurse, or whoever) might take time to develop. While available information might help us weed out the true duds, realizing that a particular doctor seems to be doing well by us might be more like finding a fine wine than picking a tasty ice cream flavor: an acquired taste.

August 1, 2013

In which I face the hard questions

Cross-posted – you know where. The Talking To Your Doctor blog!

Your book is called Talking to Your Doctor but really it’s doctors who need to learn how to talk to patients. Doesn’t this expect too much of us? After all, our doctors don’t have enough time to talk to us anyway.

Our intuition tells us that doctor-patient visits are subpar because there’s not enough time. However, research shows that patients and doctors can have satisfactory visits in countries where the general practitioner has even less time for the visit. In the book, I point out that it’s not so much the “clock time” devoted to the visit as it is the “visit time”: the attention, mindfulness, and concentration each party brings to the interaction.

Read more questions and answers at the National Physicians Alliance website.

Cross-posted – you know where. The Talking To Your Doctor...

Cross-posted – you know where. The Talking To Your Doctor blog!

Your book is called Talking to Your Doctor but really it’s doctors who need to learn how to talk to patients. Doesn’t this expect too much of us? After all, our doctors don’t have enough time to talk to us anyway.

Our intuition tells us that doctor-patient visits are subpar because there’s not enough time. However, research shows that patients and doctors can have satisfactory visits in countries where the general practitioner has even less time for the visit. In the book, I point out that it’s not so much the “clock time” devoted to the visit as it is the “visit time”: the attention, mindfulness, and concentration each party brings to the interaction.

Read more questions and answers at the National Physicians Alliance website.

July 31, 2013

Changing the emperor’s name: why do we want to rename some cancers?

Crossposted at .

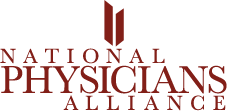

Some types of cancer, as we have known for a while, are overtreated and overdiagnosed. There was a good post at the Well blog on the topic yesterday. For the real skinny on the matter, though, head over to the Incidental Economist, who helpfully classifies cancers into three types: those for which diagnosis (detection) has increased, and mortality decreased – but due to improved treatments, not the screening tests themselves (example: breast cancer); those for which detection has increased, thus catching cancers earlier, decreasing incidence and thus mortality (example: colon cancer) – and, finally, those for which screening has increased the number of “cancers” caught, but with no benefit for mortality, because we’re just pushing the definition of cancer earlier and earlier to catch so-called “cancers” that didn’t need to be caught anyway (example: thyroid cancer).

Cancer incidence and mortality. Courtesy Aaron Carroll and the Incidental Economist.

“So-called”: for some cancers, the emperor of maladies needs to have a name change to something less scary. At least, that’s the thought put forward by some experts in the Times piece. For some cancers, the thought’s been kicked around for a while. (To take another example, the NIH State of the Science report in 2011, on localized prostate cancer, floated the idea of calling low-risk prostate cancer…something else.)

Here’s where science comes in, though, with its persnickety insistence on specifying questions and causalities. What do we think the name cancer is doing, and what are we trying to achieve by renaming low-risk cancers?

Is “cancer,” or the name “cancer”:

increasing anxiety on the part of patients, causing them to expect more invasive treatments?

increasing anxiety on the part of patients, making it more uncomfortable for them to participate in conservative (less invasive) monitoring programs?

increasing anxiety on the part of family members or partners?

Or, perhaps, sensitizing providers to the perceived wishes of patients, real or not, for aggressive treatments?

Similarly, what are we trying to do with changing the name? A cultural change to help decrease overuse? A means to decrease patient anxiety? A signal to providers to adopt different approaches?

We can’t say “all of the above,” because different strategies require different emphases. Let’s design those studies, science-types, and find out what gives! Then perhaps, eventually, the emperor will be a commoner again.

July 30, 2013

Free books!

If you would be willing to review Talking To Your Doctor on Amazon, Goodreads, your blog, or another forum that we can discuss, I can give you a free Kindle version. Leave a comment below or email me.

The book! Now in Kindle form

Whether you believe in karma, metempsychoses, gilgulim, reincarnation, or merely the attainability of desirable forms:

Talking To Your Doctor is now available for the Kindle.

It is cheaper, and more Kindle-rific. More…Kindlovian. Kindle-style. L’estile – for want of a better word – Kindle.

Thanks for reading!

Real choices: what real world shared decision-making can be like

Crossposted to Talking To Your Doctor.

I used to be a snob about people who didn’t vote because they couldn’t see themselves picking any of the available candidates. “But that’s your responsibility!” I would say to myself, self-righteously.

Thomas Hobson.

Then I became a doctor, and I began to realize that we provided these non-choices to patients all the time. Like today, for instance, when I asked a patient permission to refer her to gastroenterology for her fecal incontinence. (At least we talked about it – because she brought it up. Often times people don’t do even that much, a fact I discuss in my book reflective of the broader reluctance of patients, and sometimes doctors, to discuss sensitive issues.)

I asked, “Is that okay with you?”

Which is BS, really. I suppose it’s better than making the referral without discussing it with the person at all, but there’s no choice there. Even if I were to break down the possible alternatives – refer; take care of the problem just the two of us, me and the patient; kick the can of the problem down the road – how is the patient supposed to know what might be preferable? Heck, I’m not sure I even know.

This is what makes real-world shared decision-making so complicated. I don’t know what fraction of medical decisions are like the one above, but certainly a big chunk are. When the doctor doesn’t know what the right answer is, and the patient doesn’t know enough to have a clear preference (or no clear preference is possible), what can really be shared, after all?

July 29, 2013

Throw open the doors: fixing the primary care shortage

Crossposted to Talking To Your Doctor.

Many are worried that the increased access to health care provided by the Affordable Care Act will result in a shortage of primary care providers. There are some possible solutions which many have already written about.

Credit: spacecoastdaily.com

Train more primary care physicians

Broaden the use of family medicine

Pay PCPs better

Release the legal shackles on the activity of nurse practitioners and physician assistants

The first and second will take time. Legislation to address the third is making its slow way through the House to an uncertain end. The fourth will require a push by nursing advocates over the strenuous objections of physician guilds.

There’s another possibility: making better use of the many current specialist physicians who act, in part or much of the time, as primary care providers. I am talking about cardiologists, psychiatrists, endocrinologists, gynecologists – anyone who has a long-term relationship with a patient.

But wait – these specialists have not been trained to provide primary care! True. But we know now, in the current system, that there are few physicians (or nurses) actually providing every kind of care a patient needs without recourse to specialists. That being the case, it should be possible to figure out which elements of comprehensive care various specialists can provide – thereby enlisting the help of all providers in a coordinated effort. This is not a new idea, as a cursory search shows; but perhaps its time has come.

It should be possible, for example, to determine that Ms. Gonzalez actually sees her cardiologist the most often of any of her doctors, and, using a coordinated electronic medical record, to have her undergo colon cancer screening at that cardiologist’s office; or her medications refilled; or her immunizations.

There has been a long and storied history of cross-purposes, and even suspicion, between general practitioners and specialists. Why not turn that relationship on its head and try to share some of the increased responsibility of care coming our way?

July 26, 2013

Transactions vs. disseminations: or, better to give away than to sell

Crossposted at Talking To Your Doctor.

I cannot tell a lie or display false modesty: I just came back from a fantastic evening, reading my book at the Enoch Pratt Library in Baltimore, co-sponsored by the Berman Institute for Bioethics at Johns Hopkins. It’s no rocket science to understand why I had a good time. First, I love reading things in public. Second, selling the book I wrote is idyllic.

Two kids I am closely related to.

I must also say, though, that the reading showed me how appreciative a crowd can be even when they might not buy the book at all. Some of them did, of course, and that I appreciate. But I don’t know whether everyone did – and that didn’t matter. I felt like they had already had the same ideas that I did in the book, and together, at the event, we were transformed into a cooperative medium to disseminate the importance of doctor-patient communication to a healthy relationship with one’s provider.

It doesn’t matter who writes the book – it just matters that the ideas get out there. They are out there already, of course: that’s the point of the research I cited. They just need to be taken up by our whole system, dissolved into the drinking water.

Which is the task of our health system in all things, to move from transaction to dissemination. We don’t want to have to purchase health from a doctor, a pharmacy, or hospital – we want it to be understood and learnable from any random guy on the corner, like a language.

Can you help disseminate?

July 25, 2013

MDs! Customize care … for “selected patients”

In a recent issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, we learn that physicians generally blame other groups for the runaway train that is American health care costs: lawyers and patients, for instance. Ezekiel Emanuel, in an accompanying editorial, bemoans this buck-passing, and identifies several domains which must be changed to remake health care, with the physician in the lead. “There is no magic solution,” he says – rather, a combined approach is needed to control health care costs.

He lists the following ways in which health care delivery must be transformed:

More cost consciousness in decision making

Increased emphasis on keeping patients healthy rather than treating exacerbations of chronic illness

A move toward team-based care delivery and away from individual practitioners

More organized and coordinated systems

More process standardization with customization for selected patients

Greater price and quality transparency

Do you notice what I notice about this list? It’s centered on the provider, or the team, and not on the patient. Patients in general aren’t cost conscious; it’s not clear whether preventive health, rather than treating exacerbations, will actually lower costs; who knows how patients will react, in general, to the team-based care promised by medical homes; price and quality transparency doesn’t improve outcomes, at least according to a review we published this year.

My favorite point, however, is the “process standardization with customization for selected patients.” Which processes can be standardized with only “selected customization” – that’s my question. Is cardiac catheterization *ever* done exactly the same way in two patients? What about treatment for pneumonia? Blood pressure control? Depression treatment?

I’m not being flip, or at least – I’m trying not to be. The article, in its population-based naivete, points up the gap between cost-saving measures and patient-centered care – while failing to recognize it at all. Selected customization, indeed!