Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 24

July 12, 2013

Como comunicar con el doctor: asuntos de “traducción”

Tengo de placer de trabajar como un instructor en la clínica de residentes en el Johns Hopkins. Frecuentemente vemos a pacientes que hablan una u otra idioma aparte del ingles. Es necesario, claro, que los médicos en formación se aprendan como comunicarse con un paciente con la ayuda de un interprete. Sin embargo, tenemos también aclararse para estos doctores menores, que ese no es suficiente. Tienen también entender que cada paciente, de una manera o otra, habla “otro idioma”: se usa de palabras diferentes para describir sus problemas de salud; o simplemente no se disfruta de la amplitud de oportunidades que están disponibles para la gente con las ventajas económicas y sociales, y por eso tienen que expresarse de manera diferente, con creencias de salud diferentes del medico. Es decir: cada interacción entre el medico y el paciente se depende en la “traducción” entre dos idiomas, del paciente y del medico. Mi libro nuevo, “Como Comunicar Con Su Medico,” se ocupa de estos complicados y urgentes asuntos.

The languages patients speak (or: 5 days till Talking To Your Doctor!)

Cross-posted, of course, to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

I am privileged to work as a preceptor (teacher) in our residents’ clinic, where junior doctors learn how to provide care tailored to individual patients, many of whom have multiple significant medical problems. One thing that all of our residents should learn is the care of a patient who speaks a language other than English. For such a patient, if you don’t speak their language, you are supposed to provide an interpreter. That’s a way to provide minimal care, but not necessarily to provide good care. Interpreters might be only intermittently available, or for some languages, not at all; interpreters might not be well trained for the medical encounter; and practitioners might labor under the illusion that an interpreter guarantees good communication.

from sil-lead.org

But a broader realization needs to be conveyed as well: every patient speaks a different sort of language. The patient from a different group or culture might express themselves using health beliefs, or health vocabulary, that differs from the doctor’s. A patient who is not fluent in the language of the health care system, or of privileged America, might be tongue-tied before the doctor.

The resident, or indeed the attending, might make the same mistake with these speakers of “other languages” as they do with speakers of other languages as ordinarily understood: thinking that it’s okay to get by, make do with the minimum because that’s better than nothing. In these cases, though, the doctor needs to be their own interpreter. That is hard – to speak in English but make the “translation” to the terms appropriate for a different sort of person. But, from a communication perspective, medicine is not a communicative profession without it.

July 11, 2013

On the radio

Catch a radio discussion about Talking To Your Doctor today on the Dr. Melanie Show, 1pm Eastern, 10am Pacific. http://www.voiceamerica.com/show/1929/the-dr-melanie-show

July 10, 2013

How and why do people want to be involved in making decisions about their healthcare (or: 6 days till Tallking To Your Doctor!)?

Cross-posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor.

From engagingthepatient.com

Yesterday I spent the day at a panel sponsored by the Institute of Medicine meant to encourage the broad adoption of shared decision making: that is, a culture where doctors and patients help each other work towards a decision that’s right for the person seeking care.

Of course, my first question to myself (which I raise only occasionally to others) is this: what are the assumptions here, and how is this going to help people feel better and live longer?

The assumptions are that people – most people? the average person? the person living the most engaged and healthiest life? – want to be involved in making health care decisions. Advocates of shared decision making like to point out that this is self-evidently true.

But, as I point out in my book, it’s just not. Not because people are passive and would like doctors to walk all over them, but for any number of other reasons: they assume that doctors are in general skilled and have the patient’s best interests at heart (sometimes true, sometimes – unfortunately – not); they are intimidated and made uncomfortable by the determinedly alien nature of our healthcare system; they are too stressed, poor, uneducated, or sick to keep their mind on anything so complicated as a healthcare decision. One solution to this just-not-so (or the “yeah-but” of the real world that gets in the way of many ideologies) is to explicitly encourage patients to take that step in sharing decision-making with their doctors, to become the passionate self-advocates that many assume we all should be.

But when that doesn’t work, we should realize it’s not patients’ fault, or doctors: we need to remake our system. There are plenty of routes to do so. We can encourage doctors to involve patients in decisions by giving them money to do so; we can put more information in the hands of patients and explain it in a way they can understand; we can make it easier for poor patients, or those from disadvantaged groups, to access the care they need. Or – again, as I point out in my book – we can invest in the emotional foundation of care, a working patient-provider relationship that makes shared decision making more sustainable.

Does shared decision making lead to better health, less unequal care, and lower costs? It has that potential, at least for the first of those three. Whether shared decision making is the right star to chase, the direction to go in through the desert that will lead us to the triple aim of better care, lower costs, and greater satisfaction: that, I don’t know. My personal preference is for communication and relationships to be our north star. I can believe in SDM, though, too!

July 8, 2013

And now a word from tomorrow: will single-payer health care take gay marriage’s path to success?

If I may, a blogpost about something other than the book. Last week I went to a happy hour at a Baltimore watering hole* organized by the National Physicians Alliance. The NPA is an organization that I have felt warmly towards ever since they started the ball rolling on the Choosing Wisely movement. It is a group that wears its ideology and advocacy proudly on its white-coate sleeve and hanging from its stethoscope. (I talk more about the Choosing Wisely campaign in the book, which means this post is actually related. Whew!)

The people I met there were wonderful and of that ideology: primary-care centric, against the blandishments of Big Pharma, for evidence and for the patient at the same time. I don’t remember their names, but many of them were in preventive residency programs (most at Hopkins) and a number were specialists in family medicine.

It was with a family medicine doctor that I had the conversation that sticks with me most, more even than the beers I had. I told him I thought a single-payer health care system would never be a reality, and he pointed out that it could, on a state-by-state basis. While all such state-level single-payer proposals have failed (except in Vermont), it wasn’t too long ago that gay marriage was illegal in all states – and that too has made its way to legal acceptance through piecemeal, state by state progress.

Which is not to say that these issues are entirely comparable, of course. The permissibility of gay marriage is to my mind a moral cause, and not a hard call at all, while incrementalists have made powerful arguments that single-payer health care is not the only way to go. The long-term question, I suppose, is what comes next after the Affordable Care Act (i.e. Obamacare). Will access, quality, and (hopefully) cost continue to be improved under our employee-based model? Or will we make that leap that I more and more think is necessary, to care for all, indepdendent of employment?

The get-together with the NPA folk was inspiring. And, since most of them were a fair bit younger than I am, it bodes well for at least a corner of the future of healthcare.

*The Brewer’s Art, where I was excited to see an artisanal beer called Migdal Bavel [the Tower of Babel, in Hebrew]. How often do you see a Hebrew-named beer in the US? So I asked for it from the bartender. Who couldn’t understand what I was saying until I pointed it out on the list. I guess my beer-Hebrew pronunciation is off.

July 6, 2013

How can we make our way to minimally disruptive medicine?

This was a guest post at the Minimally Disruptive Medicine blog by the kind invitation of Victor Montori, MD.

How can we get more clinicians to help the patient receive minimally disruptive medicine? The answer might lie in the improvement of patient-clinician communication. For many conditions, the doctor is encouraged to look into the book – or, more likely, UpToDate – and read out the recommendations of the latest guideline.

But there are two limitations to guidelines. The first, of course, is that all guidelines, whether from the United States Preventive Services Task Force or the International Association of Quackery, are only as good as the methodology and evidence that go into them. The second is that even the best guideline is not a magic recipe for appropriate care for the individual person in question.

If you are discussing screening for prostate cancer via the PSA test, whether you are a patient or provider, you will surely realize that the guidelines of the urologists and internists are now in rare agreement: universal screening is not recommended. What is now recommended is shared decision making, a series of tasks that patients and clinicians do together to communicate about the options and to deliberate to identify the one that fits best with the patient preference and context.

Whether it’s prostate cancer, diabetes, or depression, how can we bridge the gap from guidelines to individually sensitive care? I think there are two steps. The first, as I outline in my book, is to build a relationship between PCP and patient that can handle the intellectual and emotional stresses of decision making with unclear information. This requires mindfulness; emotional readiness; and specificity and clarity of options.

The second step is to contextualize clinical recommendations in a way that only good communication makes possible. Such contextualization is now being addressed by some fascinating new research. We have already known, through the work of communication researchers (chief among them Debra Roter), how to characterize a true dialogue between patient and clinician.

Unfortunately, the evidence is mixed as to the extent to which such dialogue leads to improved outcomes. In their recent work, Saul Weiner and colleagues at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and at Duke University, try to determine how often physicians take the next step after good communication: using an appreciation for the patient’s individual concerns and customizing their recommendation on that basis. It’s not enough to empathize, in other words, about someone’s job loss, poverty, broken family, or inability to navigate our health system: the doctor’s care must respond to those individualities. They find that physicians who manage that customization offer care which is more appropriate to an individual’s given situation (here is a video that demonstrates “red flags” about contextual issues designed to prompt clinician response, which rarely took place).

We know that maximally invasive care is often a shortcut taken by physicians (and patients) overwhelmed by the complexities of possible options, and daunted by the challenge of modifying medicine to a person’s unique needs. Contextualizing care through good communication can give us permission to be minimally invasive when appropriate, hopefully for the benefit of person and system alike.

July 5, 2013

11 days until Talking To Your Doctor!: Turn Clock Time into Visit Time

July 3, 2013

Why do people go see their doctors? (or: 13 days till Talking To Your Doctor!)

Cross-posted to the blog at Talking To Your Doctor. Hey, did you know you can preorder the book there too?

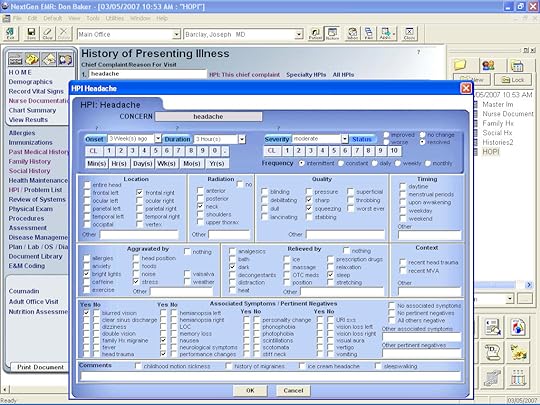

At Johns Hopkins, we now have a brand new electronic medical record (from the EPIC quasi-monopoly). I am liking it more than I thought I would. But one of the downsides of computer record-keeping is that free form narrative is trapped in forms and checkboxes – which come to think of it is no innovation of the computer age, merely something facilitated by it. Thus the patient’s story about why they came to the doctor is shaved down to one phrase or sentence which fits into the “Chief Complaint” box in EPIC. Of course, even that sort of limited reason can be of interest. For example, a recent study from the Mayo Clinic, too recent to include in my book, counted up the non-acute (i.e., chronic, or long-standing) reasons behind the visits of about 150,000 thousand patients. The most common problems were joint issues, skin complaints, “disorders of lipid metabolism,” and upper respiratory infections. Fascinating: how many of the patients with “lipid disorders” came with numbers out of the so-called “range of normal” which they thought needed treatment only because a drug exists to do so? How many complaints could be dealt with over the phone, or by email? How many lipid panels are done unnecessarily?

On the other hand, often the reason-for-visit expressed in a phrase or two often doesn’t get down to the nub of what brings one of us in to see our doctor. Often we are sidewinded by pain, knocked out of breath by a death in the family, beset by fatigue and futility, or with too many problems to count. Sometimes I can’t limit someone’s complaints to just two or three because they have a dozen or more.

This is just to say that counting the reason for a visit is important, and useful. But sometimes we can also refrain to count and just let the story be told without any interference. That could be a visit more narrative than EPIC.

July 1, 2013

What if the doctor’s not the kind you like? (or: 15 days till Talking To Your Doctor!)

It’s now about two weeks till the book comes out. As an appetizer, I’ll be writing brief posts almost every day till then about topics relevant to each chapter. Today, it’s chapter 1, where I talk about the most frequent procedure – the medical interview. As usual, this is crossposted.

The conversation between the doctor and the patient is the most common opportunity for the doctor to try and heal. As I point out in the book, there are many ways in which this conversation is often suboptimal, overlooked, and given short shrift in medical education: both in the training of medical students and in the continuing education of medical professionals.

On the way to what we hope will be systematic reform in both professional practice and medical education, which will privilege personal interaction over the quick fix of reflex procedure or lab test, it is – unfortunately – mostly up to the person adrift in our health system to find the doctor it is actually possible to talk to.

Which kind of doctor should that be, though? Ideally, you find a combination of skill, knowledge, personality, and sympathy, someone you can stick with for a while. Like as not, that person does not exist.

But if we stick it out with the imperfect person who inhabits the exam room, perhaps we can train them to be a better doctor (or nurse, or PA). Yes, part of our role is to improve matters even if we are the patient, even in the midst of our pain and illness.

The doctor has to measure up but we have to help them do it.

June 27, 2013

Radio appearance Monday, August 5th, 1pm: Midday with Dan Rodricks on WYPR

Monday, August 5th, 1pm [rescheduled from July]

Live at http://www.wypr.org/listen-live

Listen anytime later at

http://www.wypr.org/stationprogram/midday