Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 28

December 30, 2012

Blogging from an exhibition

I recently took in the newly renovated Contemporary Wing at the Baltimore Museum of Art, and was very taken by some of what I saw – so I decided to share it with you. What do you think?

by some of what I saw – so I decided to share it with you. What do you think?

December 26, 2012

from Fields, by Dovid Hofshteyn (1912)

There on night’s blue snows

among tree branches bare

my guard, my angel paces

from the first, the mute pains there.

Under the high hot sky

neath faraways sunlit and wide

my wanton youth is gliding

in a frame of golden rye.

Clear skies. Expanse of snow:

My first, my purest memoriams to you!

Original here. My translation from the Yiddish.

December 16, 2012

Unsigned notes

We’re supposed to sign all our doctor’s notes in the old system so they can be carried over to the brave new one. But even when all our notes are squared away, and even when the new system fixes the flaws of the old (“and adds some extra, just for you”), there will be the same disconnect between chart and patient.

The chart, especially electronic, is a linear sequence of notes. But the patient lives continuously and her problems get worse or better even when we are not in the room with her.

The patient’s life is pockmarked with tragedies, illuminated with joy. But our chart entries are all moments pinned awkwardly to the screen with dissecting pins.

The patient is a person. We don’t take them for all in all, but split them up into medical components: and then we wonder, when we read our own charts, why it’s so hard to get a sense of the woman we have seen for years. And the patient wonders, when she sees those notes herself, why it doesn’t sound like her at all.

There are attempts, like narrative medicine, to record the manifold experiences and emotions of the person who sits in front of us. But they are not what happens in the vast majority of doctors’ offices, where we measure out someone’s life and health in fifteen-minute increments and electronic boxes checked off just so.

December 9, 2012

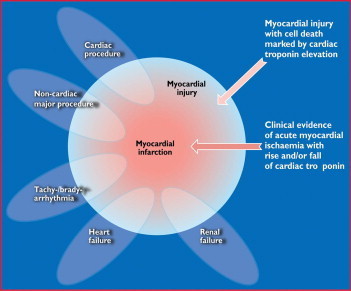

When hearts attack: changing the definition of myocardial infarction

How does a doctor diagnose your collection of symptoms as a heart attack (it shouldn’t happen to you)? The answer used to be – by a combination of biomarkers (the results of tests that measure the level of molecules, such as troponin, which are a result of damage to the heart muscle), changes in the electrocardiogram (the heart’s electrical map), and the clinical characteristics: the story someone tells about their chest pain, or their shortness of breath, and what secrets they give up on physical examination. This combination was susceptible to clinical judgment. Someone could present with typical signs in one, two, or three categories and still be classified as having a heart attack.

Comes the American College of Cardiology in October and publishes a new set of criteria which focuses on the definition of infarction as any tissue damage in the heart due to ischemia (lack of blood flow). Not all causes of infarction are the same, of course; acute damage is different from chronic ischemia, which in turn is different from damage to the heart muscle owing to other causes.

But a basic threshold, I can’t help thinking, has been crossed: the heart attack, the sudden death of heart tissue, has been nuanced and ever so subtly cast aside in favor of a basic physiological-biochemical understanding of cardiac physiology.

I am pretty sure this is all to the good. If causes of cardiac muscle damage can be distinguished, then we should we able to figure out which tests and treatments are appropriate for these different causes. Not every instance of cardiac damage is a heart attack.

But, as always when new knowledge is hammered out, the old definitions stay behind. There is a simplicity to the “heart attack.” We need to convey the subtlety of these cardiological definitions while retaining the lifesaving urgency of the old notions.

December 2, 2012

Neither-nor

Is medicine an art or a science? As an academic discipline, that people write books and do research about, it’s probably a little bit of both. But the practice of healing which involves a doctor (or other health care provider) and a patient talking together is neither of the above.

Science is law-bound.* But there are no laws of healing. A patient could very well reject a treatment the doctor finds necessary and feel better than she might have felt by following his advice.

Art creates beauty.* But healing can fail to make anything from tragedy. Tragedy carries all before it and healing doesn’t necessarily make anyone feel better.

Healing is a necessary activity, part of being human: an end, not a means. It is not art, nor science, but a kind of living.

*Philosophers will squawk at these simplifications.

November 25, 2012

Brooding peace

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–89). Poems. 1918.

22. Peace

WHEN will you ever, Peace, wild wooddove, shy wings shut,

Your round me roaming end, and under be my boughs?

When, when, Peace, will you, Peace? I’ll not play hypocrite

To own my heart: I yield you do come sometimes; but

That piecemeal peace is poor peace. What pure peace allows

Alarms of wars, the daunting wars, the death of it?

O surely, reaving Peace, my Lord should leave in lieu

Some good! And so he does leave Patience exquisite,

That plumes to Peace thereafter. And when Peace here does house

He comes with work to do, he does not come to coo,

He comes to brood and sit.

* * *

Between the first and the second stanzas, Hopkins’ Lord takes away (reaves) the bird of Peace. The alternative would be to think that the bird itself is reaving something away, which seems implausible. The dove, which sits and coos, is replaced by a different sort of winged creature who broods and sits.

We are familiar with another brooding in a more famous poem of GMH’s, God’s Grandeur, in which the Holy Ghost broods over the world with “warm breast and with ah! bright wings.” One of the fruits of the Holy Ghost, as far as this non-Christian can figure out, is supposed to be peace. The connection I feel is to the Jewish Shechinah.

In any case, the language of “brooding” attached to this presence perhaps is to be traced to a popular 18th-century theological work, John Gill‘s Exposition of the Old Testament, in which it is said that the spirit of God in Genesis “brooded” over the face of the deep.

The work of peace, as frustrating as it is, is part of the labor of creation itself – perhaps the “work” that Peace comes to do.

November 18, 2012

The leaning tower of blood pressure management

“What’s my blood pressure, Doc?”

“143/94.”

“That means I have high blood pressure, right? We should start a medication, shouldn’t we?”

Here we have a layer cake of definite maybes. On the bottom layer: the error inherent in measuring blood pressure. 143/94 is just an estimate . If by some superpower we were able to check the same blood pressure on the same person at the same time of day, everything the same, but do it 100,000 times, we might get something a few points lower (138/86, say) or a few points higher. Some of these might be under the magic 140/90 cutoff. Blood pressure itself fluctuates according to time of day, and often – this is the icing on the cake – is not measured in the doctor’s office according to the best evidence. Some have suggested payment incentives to make sure doctors’ offices measure blood pressure correctly.

The next layer is the connection between blood pressure treatment and outcomes that matter to people, accepting for the sake of argument that the person in the dialogue above has, in fact, “mild hypertension” (less than 160 over 100), with no previous heart disease. In a recent meta-analysis from the Cochrane Collaboration, the authors concluded the following:

Antihypertensive drugs used in the treatment of adults (primary prevention) with mild hypertension (systolic BP 140-159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90-99 mmHg) have not been shown to reduce mortality or morbidity in [randomized controlled trials]. Treatment caused 9% of patients to discontinue treatment due to adverse effects. More RCTs are needed in this prevalent population to know whether the benefits of treatment exceed the harms.

The final layer is whether, despite the inconclusive studies, medications for blood pressure in this person, as opposed to diet and exercise, would have a net positive as opposed to negative effect.

All that, balanced on the knife-blade of a single visit, with you waiting for your doctor’s answer.

Another slice?

November 11, 2012

“People like you might live to be 50.” “I’m 58.” “I’m not predicting.”

The blogosphere is alive with the sound of Silver – Nate Silver, that is, the head of what should be called the Five Thirty Eight Modeling Agency. Silver constructs statistical models to calculate the probability of electoral outcomes. Though he hasn’t shared his model yet, the results fit his model very well.

Is that the point? Statistical models can be constructed to serve various ends, among which are predictive modeling (“Five Thirty Eight says Obama will win”) and descriptive modeling (“in elections like these, the incumbent wins 35% of the time”). While Silver protested that he wasn’t trying to predict, only to model [at a 538 post I can't find right now...can anyone oblige?], the two often overlap. Many disciplines care about prediction and de-emphasize explanation. (A nice article about the overlap between prediction and explanation is here.)

This difference gets to the heart of how impressive Silver’s feats of statistical strength really were. If he was just predicting, any pocket calculator could do to average the polls and estimate that, in fact, Obama was a few points up. But this sheds no light on how Obama won or on what future candidates are likely to accomplish.

The same difference is also relevant in medicine, and how doctors often explain things to patients. A patient asks me if she should take an aspirin to prevent heart disease. I trot out the often used Framingham model. Like many models, it’s a little bit country and a little bit rock and roll: it assigns probabilities to certain events, spitting out a 10-year probability that a person will develop heart disease. On the other hand, it also explains heart disease as largely dependent on a number of underlying factors.

Unfortunately, these models aren’t very satisfying to us or our patients. They don’t predict very well, and their explanations, though sensible, don’t help much in telling patients what might happen to them. At the end of the day, we all have to decide about our health based on incomplete information. If the model says we are at 50% risk of developing heart disease in the next 10 years, we have to interpret this proportion not as an oracular judgment that will chase us like something out of a Greek tragedy, but the best guess of a predictive model that was based on the history of populations. We as individuals are always different.

To put it another way: Nate Silver had a relatively easy time of it when you compare his task to the doctor’s. He had oceans of data to swim in to predict (or explain) an outcome that has come about 45 times. But, for our patients, the most important outcomes happen approximately once, and missing them is deadly.

November 4, 2012

Very well then, we contradict ourselves

Sometimes I trip myself up when talking because I get caught up in the complications. My bias is to see things as irreducibly complex. There were great scholars of the Talmud who found themselves unable to judge questions of rabbinic law because they could see too many sides. Recognizing that I am not in that league, neither in medical nor in Jewish scholarship, I do feel the same way on many occasions. “Should I take medication for high blood pressure?” “It depends.” “On…?” “On your cardiac risk, your tolerance for adverse effects, your potential to lower your blood pressure with diet and exercise.”

Now I realize, way too late, why all those jokes about “six months to live” are even funnier (or, perhaps, even less funny) than people realize. Of course the point of those jokes is that the doctor is way too sure of himself (it’s always a he in the old jokes). But even deeper, the doctor is wronger than he knows. No one can tell how long anyone else is going to live.

In a recent daily page of Talmud, the rabbis talk about how the books of Ecclesiastes and Proverbs were nearly kicked out of the canon because they were self-contradictory. Somehow, they managed to stay in: but that’s never said explicitly, since the reader knows that. Rather, what comes directly after the attempted aspersions on these books is a series of exegeses to make all the contradictory verses work out.

The message for me as a doctor: we are purveyors of narrative in a shifting landscape of multiple truths. To tell a story that works for our patient is being helpful, not deceptive. A story to take our patient through a disease and out the other side is worthy of inclusion in our canon of healing.

October 29, 2012

Going back

This past week I started teaching medical students for the first time as an attending physician. It’s a new start, but of course it’s also a return: the last time I taught medical students was as a senior resident.

Treating patients in the hospital is something I’ve done even when I haven’t been teaching, of course, but teaching increases one’s powers of observation if only briefly. What I notice now is that, as doctors, we spend most of our time not in rooms but in corridors in the hospital: hurrying back and forth, holding whispered conversations or rounds at full volume. “Prepare yourself in the anteroom,” says Pirkei Avot, a basic ethical-moral work in the Jewish tradition, “to enter the palace.”

On the other hand, my daily work is in the outpatient setting, the clinic. Patients wait not in their sickrooms but in their chairs of delay, while we work things through in our chambers.

In the hospital we’re always hurrying about while the patients wait; our activity is often an illusion and there’s much we can’t speed up. In the clinic, we are all on the same clock.

Medicine comes in many different mixtures of waiting and action, passivity and frenzied procedure, and I want some way to tell the students that neither hospital nor clinic is all there is.