Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 30

August 20, 2012

Overuse from flu to you

Antibiotic overuse is a big problem: it contributes to antibiotic resistance, changes the distribution of beneficial bacteria within our bodies, and, more generally, is an example of a wider problem, treatment that doesn’t work which many people continue to expect anyway and thus ends up prescribed on a wide scale.

Some common circumstances in which antibiotics are given when they shouldn’t be include upper respiratory infections. A fascinating piece of research in the latest issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine addresses a question relevant to those infections and antibiotic overuse: Does the context of a patient’s illness – that is, the other illnesses that the doctor might have seen around the same time – affect the likelihood of prescribing antibiotics for febrile illness? The answer is a qualified yes: that is, as the number of cases of febrile illness that a doctor had seen during the previous week increased, their likelihood of prescribing antibiotics for the case seen decreased. In other words: if the doctor was exposed to more cases of what were likely flu, or flu-like, they were less likely to give antibiotics.

As interesting as the article itself was the accompanying editorial, which talked about the multiple factors contributing to antibiotic overuse. Sometimes patients want them even when the doctor thinks they don’t work; sometimes the doctor thinks they would work when they wouldn’t; and sometimes the doctor isn’t sure what the true diagnosis is, and prescribes the antibiotic just in case the illness is bacterial.

The last paragraph of the editorial hits the nail on the head:

How exactly [does] knowledge about the [flu] pandemic enter into interactions between patients and clinicians? This is a relevant question because antibiotic prescriptions for repiratory illnesses are usually the result of a verbal negotiation between a patient (or parent) and clinician, during which different perceptions of the illness and appropriate course of treatment may be at play. … On-the-ground observations not only produce …. nuanced explanations of clinical priorities and practices, they can also disentangle the complex interplay of tacit knowledge, social norms, economic pressures, and broader cultural trends — all of which shape patients’ preceptions, clinical resoning, and prescribing decisions.

Even more relevant: antibiotic overuse is just one kind of overuse. As we become more attuned to the general problem of overuse of multiple diagnostic tests and therapeutic modalities, we should try to understand the culture of overuse underlying all of it.

August 13, 2012

Foreseeing problems

Another problem with implementing healthcare standardization on a large scale is that there’s no possible way of judging empirically whether it will all work. (Standardization is the question here. Other issues are easier. For example, I think it’s uncontroversial at this point that expanding healthcare access will save lives.) Neither is there an experimental design which could test the question. We basically have to take it on faith that checklists will scale up to entire healthcare systems.

Is there a way to foresee problems when large systematic change like this is undertaken – in any field, not just medicine? I am asking you, dear readers, because it’s frankly something I haven’t looked into much. Did anyone say, wait a minute, we shouldn’t construct a huge network of interstate highways? Or: let’s think a minute before we build and test an atomic bomb?

There are instances where people did stand athwart history and yell Stop. Iraq comes to mind. But political change, war and peace, seems different, more reactive, than systematic change which we try to initiate on an a priori basis.

Of course, I don’t think healthcare standardization is per se dangerous. I just think, per my previous post, that much of what’s worthwhile in healthcare is not currently quantified. Not unquantifiable as I said before, but currently understudied. Do we know enough about what will be left behind if we move forward under our current, imperfect assumptions about quality?

August 11, 2012

Day and night

Day and night -

We wait frozen in angry day

for night with its moon,

for moon’s tenderness.

We wait terrified in angry night

for day with its sun,

for sun’s mercy.

Day and night -

They think we’re big,

they make free use of us.

We’re small, quite small -

Fear pulls us to the ground,

as if we’re his, as if he owns us.

So small, what should we

do with ourselves?

Our pain, what should we do

with our pain?

Love?

Secrets?

Day and night -

They think we’re big,

they make free use of us.

–Leib Kvitko (Oct. 15, 1890-August 12, 1952)

–Leib Kvitko (Oct. 15, 1890-August 12, 1952)

(my translation; original here)

August 10, 2012

“One of the kosher arts”: Women writers set the tone for Charedi culture

“Women are getting the short end of the stick” in the literary world, said the novelist Jennifer Weiner last year. Weiner’s observation was informed by the work of VIDA, a non-profit organization which counted the women writers and editors represented on the pages of top-tier magazines, showing they are significantly outnumbered by their male counterparts. Our culture (as its website had it) underappreciates women’s literary creativity.

But the place of women in literary culture depends on what culture you belong to. There is a world whose bestselling authors and mass-circulation dailies and weeklies set the tone on multiple continents for dinner table discussions, conversations in the supermarket, chats at aerobics. Or perhaps at shul and in the mikvah. The vast majority of these authors are women, and you’ve probably never heard of them, unless you’re strictly Orthodox.

Frum women’s lit has come of age, and with it a unique set of contradictions and contributions. How can women writers, bound by communal strictures, find creative freedom? How does anyone learn to write without reality shows to snark about? And what does their writing say about their society and women’s place in it?

Read more in Tablet.

August 9, 2012

Atul Gawande likes his cheescake: or, where metaphors fail patients

Atul Gawande is a technophile and a believer in the checklist, and he yokes these ideologies to an attractive metaphor in his newest essay for the New Yorker. The article is worth reading in its entirety, but it can be easily paraphrased. The Cheescake Factory, like other successful restaurant chains, has “brought chain production to complicated sit-down meals.” They’ve done it by far-reaching standardization of the best possible processes – but not all the way down, since some freedom is left for the front-line practitioners, for example, the line cooks, to get the job done according to their personal practices. Flexibility is built into the restaurant’s practices, which change regularly according to new data. And customers are satisfied.

Health care in the United States, on the other hand, does none of this currently. Practices are incredibly diverse, often for no good reason. Particularly touching – as in so many of Gawande’s articles – was a story that he elicited from a Cheesecake Factory employee, Dave Luz, a Cheesecake Factory regional manager in the Boston area. Luz’s mother, aged 78, had a fall and was subjected to the depressingly normal dysfunctions, malfunctions, miscommunications, and screwups of an American hospital. And, when it was time for her to go home, no one coordinated anything. It was up to Luz to do everything, even get her dressed.

An aide was sent. She was short with him and rough in changing his mother’s clothes. “She was manhandling her,” Luz said. “I felt like, ‘Stop. I’m not one to complain. I respect what you do enormously. But if there were a video camera in here, you’d be on the evening news.’ I sent her out. I had to do everything myself. I’m stuffing my mom’s boob in her bra. It was unbelievable.”

A terrible story. Gawande concludes eventually with a not unexpected conclusion. Standardization should change American medicine. Best practices do not make it down to the medical equivalent of the line cook. Doctors bristle at being told to do things better. “Already, there have been startling changes,” Gawande reports with excitement. “Big Medicine is on the way.”

He tips his hat to the obvious objections. Are we ready to make medicine into Walmart? What about accountability and transparency? “Some will see danger in this. Many will see hope. And that’s probably the way it should be.”

But one problem doesn’t make its way into the article in more than dribs and drabs. Does it work? Does massive standardization do the trick? Of course, we know that checklists work wonders in the critical care setting (from which Gawande presents most of his anecdotal evidence).

But in nearly every other area of medicine, people are still hotly debating whether standardization, or as Gawande puts it, quality control, makes people less sick or helps them live longer. Does giving antibiotics within a specified timeframe actually keep people from dying from pneumonia, or increase the unneeded use of those medications? On a larger scale, do the incentives provided to accountable care organizations actually improve care?

There’s an even deeper problem. What do we do about the majority of medical concerns for which there is no standardization? What happens when clinical judgment, often based on little more than anecdote, meets patient preference? Perfecting the mashed potato tower and slicing the avocado to a quarter of an inch is perhaps quite like fine-tuning the ventilator settings or turning down the oxygen. Critical care involves many quantifiable judgments. But what about all the non-quantifiable judgments?

And what about all the parts of medicine which are not strictly quantifiable? That aide who manhandled Luz’s mother: what standardization would have kept that person from acting like a jerk? Employees are only as good as the organization hiring them, but human beings act only as humanely as their capacity for compassion allows. The technophile’s faith will always let him believe in the perfect cheesecake in the next concession over. But the astute skeptic, the careful consumer of metaphor will realize that sometimes a patient is a patient, not a dish off the menu.

August 6, 2012

Daffy doctors: the rewards and superficial accomplishments of daily study

Thousands of Jews around the world recently celebrated the end of this round of the Daf Yomi, a seven-year cycle of daily Talmud study. Obviously there is no equivalent regimen of daily study in medicine.

Or isn’t there? Medical education, even continuing education of professionals, goes through many fashions – just like Judaism does (the Daf Yomi is less than a hundred years old). When I was a medical student, it was said of some our mentors, always in tones of awe, that they read a page of Harrison’s every day. Harrison’s is a stupendoginormous chunk of book, weighing in at over 1,000 pages and purporting to encompass within its unembarrassed girth every bit of internal medicine.

I don’t know if anyone does the Daily Harrison’s any more, but I know that daily study, or at least daily acquaintance with new bits of knowledge, is still an activity with quite a number of adherents. I happen to be one of them. Like many other doctors, I subscribe to a number of email lists which present digests of new research articles. Many journals offer updates of the latest developments of medicine. So, in fact, part of my daily ritual in the study of medicine is opening up my inbox and learning my daily dose.

The critiques that have been made of the Daf Yomi can also be made of the scientific literature. The latest is always made out to be the greatest. The new page, the new journal-article digest, rises to the uppermost level of our minds and stays there only until a newer bit of news displaces it.

Learning this way, day to day, we only glide along the surface. There are uncountable riches beneath each page of Talmud – links among pages; commentaries on each passage; application of theory to Jewish practice past and contemporary. Similarly, each journal article is a thumbnail sketch of a vast landscape of medicine: the research literature for any significant topic stretches back years and multiplies logarithmically.

And it’s even more incomplete than that: because the refreshers of the medical literature ignore two huge facts. (1) Not all the literature is scientifically sound, even the links that make it to the email digests. (2) Not all of medicine is evidence-based: to take a few examples, our relationship with patients, our ethical and societal responsibilities, and our self-image as doctors are affected by things quite outside the realm of ACP Journal Club (which I like a lot).

Thus, much as the Daf Yomi is looked at askance by many, the daily email digests, the blizzard of articles, and the heady but unrepresentative 30,000-foot view of medicine are not ideal. We need to recognize complexity and factor it into our practice and self-image as providers.

How do we do that? Should we make an effort to express the complexity of medicine in an explicit way to our patients and colleagues? As some Talmud learners – perhaps just to be difficult – sniff at the daily dose of learning and seek out depth, should we doctors, even those of us who aren’t academics, make an effort to do regular systematic reviews of the literature to inform our own practice? Maybe we should do so in partnership with our patients, as unrealistic as that might sound? Your suggestions please.

July 30, 2012

Our definitions of quality

What is your preferred quality domain, all things being equal?

Answer

Votes

Percent

Effectiveness

8

47%

Patient-centeredness

4

24%

Equity

2

12%

Safety

1

6%

Timeliness

1

6%

Efficiency

1

6%

It wasn’t a big poll, but I find the answers interesting. I asked you what the most important quality domain was. There’s nothing statistically significant here, because only 17 of you responded. (If this was just 1 person responding 17 times, let me warn you that the punishment for screwing around is severe and swift. This is a serious blog.)

What catches my eye are the several choices that lost out and ended up at the bottom: safety, timeliness, and efficiency. It could be that people didn’t really understand what these meant. (Timeliness – that medical care be delivered at the right time, i.e. neither too early nor too late; efficiency – that resources not be wasted, or underutilized, in delivering the care.)

Safety, though, is surely something that everyone understands. Why didn’t it get more votes? There’s no clear answer from this unscientific effort, but here are some speculative possibilities:

It’s something everyone assumes already exists, until they are themselves affected by subpar safety. Who judges an airline or a car by its safety record? Maybe we don’t talk about those things because we assumed that someone, somewhere, is ensuring the safety of our airline travel or automobile manufacture. Certain people, by pointing out governmental and private negligence, have forced us to pay attention to things we might not want to notice. The same is true of healthcare, but maybe that just hasn’t registered yet.

Or perhaps, subconsciously at least, the category “effectiveness” already folds in safety. If we are delivered quality care, we already assume that it will be done without errors – certainly without serious error. If our gall bladder were removed without a trace but then we got a blood clot in our leg, we might not consider that an effective cholecystectomy!

However, apart from our individual preferences, the real reason I put up this poll was to illuminate a larger problem. There is precious little research on what patients think is meant by high-quality healthcare. If we make use of new public reporting mechanisms (or reporting done by private concerns, like Consumer Reports) to tell us which doctors or hospitals are better, we should make sure that we understand and agree with the criteria.

July 27, 2012

Writing for another culture: poetry, censorship, sex, and Chasidim

There’s a Web journal in Yiddish with the name Shabbos-Blettel – that’s right, “The Shabbos Paper.” I was happy when the editors agreed to publish a poem I sent them. The submission was a complete Hail Miriam: I wondered if the Chasidim would take the poetry of an outsider.

Originally, I wrote this:

Universal and Everywhere

1.

Nothing is universal but

blood and gorge

sex and gall

lust of the phallus

graveyard reservations for us

And the smile of

disappointed feelings

which softly dissolve

like depression pills

Everywhere

banality of dreams.

Only destruction is concrete.

2.

Everywhere the air

is something everyone needs.

Except for sulfur-reducing bacteria

in underwater caves.

Ask them if suffocation

can be translated

to other creatures.

It’s better in Yiddish, I think. The editors had a simple request: could I leave out the words “sex” and “phallus” (which in Yiddish is eyver, meaning “penis, male member”)? Sure, I said, knowing that if I didn’t bend a little, my poem would never see the light of day in a Chasidic publication. I replaced the word “sex” with a Germanic synonym, geshlekht, which means – sex, but has a euphemistic flavor (“congress,” maybe, is a good English equivalent?). I replaced “eyver” with “over” – “past.” A cop-out. But the rhymes stayed the same, and the general world-weary air, not all that original, didn’t change much either.

Comes a valued commenter who pointed out that in the same issue, the editors published an essay extolling the virtues of open Internet access. Like many a Web-based Chasidic publication, Shabbos-Blettel is not “official,” and performs a valuable service in speaking truth from behind the Shtreimel Curtain.

My favorite part of the whole discussion between the commenter and the editor, appearing on Shabbos-Blettel’s web page, is the commenter’s commentary on my poem and word choice (my translation):

With all respect to the editors, I don’t understand why those couple of words are so harmful. They are certainly not pornographic or obscene. One word means the same thing that we call in [Rabbinic] Hebrew “minut,” etc., and the second word – and it’s even a euphemism – refers to the part of the anatomy that only males have…would the editors also change the famous statement of the Rabbis that “There is a small organ in man which satisfies him when in hunger and makes him hunger when he’s satisfied” [Sukkah 52b; here's an article in Hebrew on the topic]?!

And there’s a difference between “sex” and “sexy” [a word which the editors noted they did not include in their Internet article]. The first refers to a verb that is characteristic of all creatures (“other creatures” of the end of the poem), in order to create, without any moral tendencies towards good or evil. On the other hand, the other choice of word demonstrates a situation and feeling that are only connected with erotic desire. In keeping with this, the intention of the poet is to express that this is mainly an internal biological force (“depression pills,” “sulphur-digesting bacteria”) and untamed (“blood and gorge,” underwater caves”) which drives man through his nihilistic life of dreams from cradle to grave…

And when you say that the author himself agreed to the word change: look, if you read his blog you’ll see that he writes that although he changed them by the editors’ request, nevertheless “of course,” he says, “I prefer the original,” and he even asks himself if he let himself be censored.

Such readers!

July 23, 2012

The quality domains – what’s your druthers?

As was said in the report Crossing the Quality Chasm [blah blah blah]….

Every report and article on the topic “health care quality” starts this way, because the report was groundbreaking, laying out the domains that we should aspire to perfect: safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. These domains apply at multiple levels throughout the healthcare system. But as Don Berwick pointed out, our true lodestone should be the patient’s experience.

In that case, why don’t we ask how people (sorry, “patients”) feel about these domains, and what are most important to them? Of course, it’s impossible to achieve all the domains perfectly at once. Everyone could be made perfectly safe if nothing were attempted. Care could be timely if no one ever asked patients’ opinions or double checked that errors weren’t being made. And so on.

How would you make the tradeoff, if you could? Once I get your answers, we can discuss how they compare to past and present literature, and what to do about the balancing act.

July 19, 2012

Horrible but not unexpected: miscommunicated lab data at NYU

Read this heart-rending article at the New York Times about NYU’s mistake that let a septic boy out of their ER. Then read this exchange of comments on the article.

tr (Maryland)

As a physician assistant who practices in a major university emergency department, I am confused about one thing. When a patient has seriously high bands or neutrophils, the lab calls back down to the ED to let someone know. Even if the provider who ordered the test has gone off shift, the lab is given to a working provider to follow up with the patient immediately. I have personally called many patients back to the ED for a worrisome lab value, even when I did not see that patient myself. Does NYU not have a similar system? Do they now after this horrific incident?

July 11, 2012 at 4:59 p.m.

Jim Dwyer (NYT columnist)

Of the hundreds of comments here, this is probably the most salient. Why was a patient with those alarming blood values not contacted by someone at NYU? What procedures does the NYU lab use when it has these kinds of results? If a patient’s blood shows evidence of a heart attack, the lab will call the doctor directly. Why not with evidence of significant bacterial infection?

Moreover, NYU has declined to discuss how it deals with these kinds of results after a patient has left the hospital. Many people have defended the decision to discharge a patient with fever, rapid pulse and breathing, noting that these are common among children.

To lay people, it is very hard to understand why these sophisticated tests would be ordered but then not read or acted on.

I have more to say to lay people: lab tests go unreported all the time. The person who orders it doesn’t see it in their queue due to the vagaries of their EMR; a test is ordered by one physician who expects that a second will follow up on it; a lab result, for whatever reason, is classified as abnormal but not urgent or emergent merely because it does not fall within the prespecified ranges of the EMR.

The reason for all of this: our system is fragmented. We lack universal standards for communication of lab results among providers. The case is terrible but the factors underlying it have been publicized time and again.

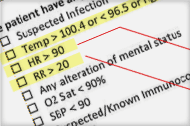

(For those interested in the lab results in this case, they are here.)