Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 31

July 16, 2012

On and off the label

The Vegas-cavorting executives of GSK recently made news for their off-label shenanigans, promoting medications for uses which had not been approved yet by the Food and Drug Administration. Bad enough.

Is it worse or better, though, to realize that the everyday practice of medicine involves an order of magnitude more questions, and more specific questions, than can possibly be addressed by the FDA?

I want to discuss with a patient the treatment of her reflux. Sure there are a bunch of approved medications available. We are taught in medical school that the proton pump inhibitors are more effective than the H2 (histamine receptor) blockers. But which of the PPIs are more effective? Which strike the best balance between cost, side effects, and symptom relief? And how do any of them compare to non-pharmacologic treatments?

There are precious few studies to answer any of these questions. Sure, let’s blame Big Pharma. They have blood on their money. But is it any wonder that doctors are susceptible to such inappropriate influence, when the appropriate variety is so hard to come by – not due to any venality, but due to the imperfections of our research system? Studies of one drug against placebo are valued; comparative effectiveness studies that pit drugs against each other are vanishingly rare. And forget about considering cost!

So sure, let’s blame greedy pharmaceutical companies for what they’ve done, but let’s acknowledge the difficult spots patients and doctors are in when they try to find the best evidence to answer clinical questions. If we figure it all out, we can celebrate in Vegas.

July 11, 2012

Reviewing Johns Hopkins’ new hospital building

There’s a review of Johns Hopkins’ new hospital building over at Baltimore Brew, but what’s really worth reading are the comments. The review itself reads like a press release from my employer, but the reactions by readers encapsulate why I feel so conflicted about the place: yes, it’s large; yes, it’s glassy; yes, the facilities are much appreciated by my colleagues. But where is the design that could have opened up the forbidding Hopkins Hospital campus? Does a hospital that looks like an airport lead to better care?

Notably absent from the review – and the comments, as far as that goes – are opinions of patients. What do they think of the place? Do they prefer it to the old hospital? And, for that matter, what do employees think? Many janitors (who are my patients) have to work harder, cleaning more square footage in the same number of hours. On the other hand, I have met people who take real pride in its scale.

July 9, 2012

Present pain for future benefit: the case of circumcision

Ritual circumcision and legal objections to it are in the news. There are two separate but related questions:

1. Whether it’s in the state’s interest to forbid it;

2. How parents are supposed to balance the risks and benefits.

Let’s take the second one first. No one denies that circumcision involves pain and suffering to the child. The long-term psychological damage does not seem to be demonstrated anywhere and seems implausible on its face, given the number of people who have been circumcised and lead happy, psychologically whole lives.

The medical benefits are beyond the scope of this post. However, one kind of benefit that is not generally reckoned, at least in secular analyses, is the benefit to the child from the ceremonial or religious aspects of the ritual. I’ve seen it said that children cannot be considered members of any group of people, since that distinction is reserved for adults. This is silly, of course. We assign children to groups all the time (“Jewish,” “African-American,” ”creative type”) recognizing that these categorizations will only be fully appropriate when the child is of age. That doesn’t mean a child can’t partially participate in the life of a group or enter into the group even upon infancy. Otherwise we would never go to the trouble of – say- giving the child a name, because only adults are completely realized individual personalities. Ritual circumcision is done to confer belonging in a tangible way.

The first and second question share one consideration. Is the pain done to the child by circumcision exceptional enough to put it beyond the pale? It’s hard to say. You could imagine a situation in which the state adopts a default position of disallowing circumcisions, while allowing certain exemptions. But circumcision is by no means the only case in which we cause a child short-term pain for longer term benefit. We draw their blood and give them vaccines. Some people let them cry to teach them to sleep alone. When they’re older, they get braces.

We spend a lot of time making children uncomfortable for their benefit. The fact that circumcision causes pain does not necessarily make it morally problematic.

July 4, 2012

Contaminated truths: Wellbutrin, depression, GSK, and evidence

Like any perpetually anxious physician, I had one thought when I read the jaw-droppingly obscene details about GlaxoSmithKline’s briberies and deceit. Well, maybe two thoughts. The first thought was that I don’t play nearly as much golf as these other doctors do.

The second thought was, “Oh my God, I hope I didn’t prescribe any of these medications unnecessarily!”

And I didn’t. Not really. Let me explain: one of the medications mentioned in the indictment is Wellbutrin (generic bupropion), a medication that is useful by itself for depression and smoking cessation. The evidence for these is untainted by Big Pharma, though it’s susceptible to the same problems and controversies afflicting all pharmacological treatment for depression.

But another claim, which I have heard for the past few years, is that Wellbutrin is useful to “augment” pharmacological treatment for depression with SSRIs. To be honest, the claim was one of many that I have heard from colleagues that I did not verify with a good look at the evidence. (How much that we have heard from colleagues, superiors, and teachers are things we haven’t verified ourselves? That’s why we should be open about our biases and ignorance, and ask patients for equal measure of skepticism and trust.)

When I read the GSK doings, I decided to check and see if what I had thought true about Wellbutrin as an “augmentive” therapy actually was true. And I found out – it is, kinda. There was a randomized controlled trial in the New England Journal of Medicine of patients who had “failed” (that is, not achieved remission of their depression) with SSRIs. They compared bupropion as augmentation (that is, together with an SSRI) to buspirone as augmentation. The results were promising. As the researchers say with commendable restraint, “Augmentation of citalopram with either sustained-release bupropion or buspirone appears to be useful in actual clinical settings. “

Taking a closer look, though, leads to some misgivings. There was no placebo group (i.e., patients given SSRI and a sham drug), and no group with the SSRI alone. Further, while the endpoints were specified in advance, and GSK had no active role, per the paper, in study design, authorship, or funding, the disclosure section of the article reads like an encyclopedia of pharmaceutical companies. All the authors were getting money from them all.

Do I think Wellbutrin is a useful augmentive therapy for depression? I’m not as sure as I was, after actually reading the paper. But the uncomplicated truth of its usefulness has filtered down to us, and spread throughout doctors everywhere, partially due to GSK’s perfidy. Without their overpushing Wellbutrin, I might have more confidence in the possibility of genuine clinical usefulness.

How many clinical truths are contaminated by pharm money?

July 2, 2012

Helping on various levels

The people in Baltimore’s poorest ZIP codes die twenty years before those in the richest. I went to a meeting on Friday to try and help the health of the poorest, at least in the ZIP codes nearest to Johns Hopkins Hospital. Federal funding is behind this, as well as considerable clinical and research expertise.

It was a great meeting with important goals and inspiring ideas. At the same time, I felt like we were all blinding ourselves to a problem. We were talking about engaging patients in their care – vital to be sure, and there are a lot of patients who don’t see their doctors, do real damage to themselves, and don’t participate in what others try and do for them. On the other hand, there is a mountain of mistrust between Baltimore and Hopkins. I felt like we were all trying to look over it, and there it was in the middle of the polished table.

How do we get over that mountain? Are good intentions and practical deeds enough? Is working with the community enough? Is there a way to apologize and make amends without shooting ourselves in the foot?

Pain, change, and Judaism

Two movements approach change in Judaism in different ways. Orthodoxy constructs a myth according to which change does not occur, at least consciously, in the halachic process. It is imposed from without, sure, by social forces and non-Jewish perfidy, but never by poskim themselves for the purpose of change itself.

Conservative Judaism claims that they have the steering wheel of halachic change in their hands and turn it only when moral considerations become urgent and primary. The Bandaid must be ripped off at some point when the gap between moral reality and halachic text becomes too great to bear. This is painful, as can be seen from this teshuvah, where – even in egalitarian synagogues – the number of women wearing tallis and tefillin are few and far between. A halachic change was made for moral reasons, and it was painful but necessary.

Orthodoxy deals pain, too, but in a different way – to classes of people excluded from the halachic process. People change faster than Orthodox halachah. Gays and lesbians and women are two obvious groups that are considered only very slowly.

Pain is part of life, and I don’t think either of these groups has a monopoly on it, or – conversely – a magic formula to avoid it. You pays your synagogue dues and you takes your choice.

June 28, 2012

Scanning tunneling theological microscopes: forbidden!

Rabbi Adam Frank recently wrote an essay in the Jerusalem Post about what’s wrong with today’s Conservative Judaism. It got me thinking.

I admire the good intentions behind Rabbi Frank’s cri de coeur but wonder how many of his deeply held convictions are defensible. I was particularly taken, or taken aback, by the following “ikkar” in his Ani Ma’amin:

I believe that faith in God is not supposed to be put under a microscope for dissection.

“Supposed” according to whom? The Rambam? The Ramban? The tannaim? The amoraim? For they all did. Perhaps you mean that they were allowed, but we are not? Why not? Can some of us? Who decides? (Artscroll, perhaps? Rav Amar?)

Perhaps only those whose faith is unquestioned (unquestioning?) are qualified. For, indeed, our frumer brethren the Orthodox must never have any dark nights of the soul. Never has an Orthodox day school ever been confronted with terrible doubts by its students or faculty. All is peace and light there.

And, if we can agree who makes this determination (without, God forbid, a hint of the “snobbery” that might attach to, let’s say, intellectual honesty), what happens if someone has questions about God or belief? I take it we hang a “No Dissection” sign across the Jewish soul and leave it at that. You’re in or you’re out. You believe or you don’t.

Thank goodness – that will make everything simpler. For we all know that when previous generations, greater than ours, set down the principles of faith (we might call them ikkarim), that no one had any problem with them. All, indeed, was Torah-true. Agreement reigned. Spinoza and Mendelssohn are merely figments of God’s imagination meant to test our faith, like dinosaur bones. Not to mention Maimonides himself.

Now that that’s cleared up, we can get to another of Rabbi Frank’s principles.

I believe Conservative Judaism should encourage our boys and men to wear kippot outside of school, synagogue and the home.

Again, why? Does this midat chasidut demand elevation to the top of our spiritual to-do list? The omission of women is telling – where are they? Perhaps on the cutting room floor? Behind the mechitzah of Rabbi Art Scroll?

Are we imitating Orthodoxy because we have thought these things through, or because we are looking over our right shoulder?

Do we really think that the current Orthodox complacency and (in many cases) self-righteousness is really reflective of an eternal truth, or merely the rightward swing of a historical pendulum? Are we sure that such calls to fundamentalism are really not just appeals to the fashion of the moment?

It would be a shame to abandon our ideals on someone else’s altar.

June 25, 2012

Trust, skepticism, and expertise

A reporter emailed me last week to ask my opinion about a publication from the United States Preventive Services Task Force that is embargoed now, but won’t be by the time this post sees the light of day. It has something to do with obesity. (See? You’re excited already!) I emailed back something bland – I found the recommendations eminently reasonable but was unsure if they could be applicable in the everyday clinical environment.

But of course I was going to be in general agreement – the manuscript came with the imprimatur of the USPSTF. Far be it from me to second-guess a manuscript that’s authored by folks who have immersed themselves in the field, actually read and thought about the 15 or 20 references, and responded to comments by the lay public ranging from thoughtful to nutso.

Why did the reporter want my opinion? Because I’m a poly-diploma’d doctor at a fancy medical school who has his name on scientific papers and is interested in evaluating evidence in a careful way. Not because I’m more expert on obesity than your average academic internist.

So the question rears its head: how can a non-expert evaluate the work of an expert? A healthy dose of skepticism is needed. Or even more – we need experts who point out that most experts are wrong.

But we need the other side of the coin too. We need to be able to trust, because we can’t check everything ourselves. This isn’t just a question of epistemology (how can we know something we can’t see with our own eyes?) but a question of emotional reliance. Sure we can’t trust everyone. People bought and paid for by Big Pharma, for example – why should we trust them?

But if structures are in place to ensure some trustworthiness, we can believe. There is a balance to be struck between radical skepticism on the one end and drooling credulity on the other. Otherwise we could never make any decision at all.

Learned Repetition

I have taught the lizard

the wizardry of rest.

Now ring the charms on sun

and earth’s bracelet. Some

theories are proven false

before their lifetime. All

is either shadow or shadowmaker.

Crowds have sourced together

shading of night’s ochre.

June 20, 2012

Scent of the Dream

When I was a child I had a strange dream: I was a shipbuilder in the time of the Crusaders. I could actually smell the sea smell, the strong odor of the algae and salt, the scent of the tree I was holding. The ship towered above me into the sky, steel-colored. I was not a boy in the dream, but a man, but my eyes were those of the boy I was then and they were captured by the transformations of the sky’s waves and the ripples that traced the quick screaming seagulls among the bare masts stripped of their sails. When I woke up I could still feel the touch of the wet wood on the palms of my hands and when I brought them to my nose they emitted the scent of the dream.

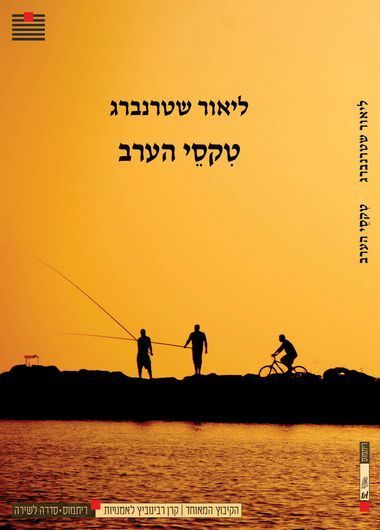

–from “From the River’s Two Banks: Fragmented Conversation”, from Lyor Shternberg’s Evening Rituals, translation from Hebrew by ZShB