Zackary Sholem Berger's Blog, page 35

March 27, 2012

All the pretty hospitals

Johns Hopkins has gotten itself some new hospital buildings, and I am conflicted. It's a beautiful building, including a new children's hospital and sparkling, still plastic-wrapped facilities for many, many things. But I'm not sure how often I'll make my way there.

That's because internal medicine has no space there (I mean internal medicine as a primary field; cardiology and gastroenterology certainly do). This is not surprising – we are not a money-making subfield. The modern hospital, after all, is built on sexy specialties, not the longitudinal spadework of the primary care provider. When I admit my patients to the hospital, they will be in the "old" buildings, and when I see my patients in the clinic, I will keep seeing them where I do now – in what is admittedly not an "old" building at all, since it was built in the long-ago aughts.

I am also conflicted about the new building's presence within our East Baltimore community, with which our relationship has not been … uncomplicated. An architect friend of mine, native to and knowledgeable about Baltimore, remarked that my institution presents a closed face to the city with its buildings. There is no streetscape, nothing beyond the blank glass. The main medical campus gets lively only when people get outside, whether it's to sit in the sun on the grass in front of the monumental Dome or buy something at the farmer's market. Thinking back to the other medical campus I trained at, NYU/Bellevue, I remember the energy that poured out from the street into the hospital lobby, and how animating it was.

The new hospital building is shut off too. Yes, it is outfitted with restaurants and cafes aplenty, but I don't know which of our neighbors will eat there or feel comfortable walking in. Maybe that's an unreasonable thing to expect from a hospital, but I hoped we could do better.

March 21, 2012

Forced Learning

When I was little

everything was going fine

I guess, at least

how I remember it.

Days like today

I ask myself

why the fuck I've grown up.

-Mercedes Castro (my transl.)

March 19, 2012

What doesn't kill you makes you suffer. And suffering?

What good does suffering do? I got in a Twittersation about that the other day, which was initiated by this quote:

"When injustice proliferates in the world it's not that God is absent; it's that God is inviting us to step up" @YUNews' Pres. Richard Joel

— Sarah Mulhern (@On1Foot_) February 22, 2012

But what about the person suffering, I responded. Do they want such an invitation?

To which there came a response:

@zacksholem @YUNews I think it's not the people suffering being told to step up, but other people, hopefully motivates them to do something.

— Sarah Mulhern (@On1Foot_) February 22, 2012

We all suffer in greater or lesser measure, because we all know illness and death – if not now, then soon. But my suffering is not yours. I cannot tell you what lesson you are supposed to learn from your suffering because I can never inhabit it fully. I can try and comfort you, telling you what I have learned from my own experiences, but instructing you what you should learn from yours is presumptuous in the extreme.

When a community suffers, however, something different happens. Experiences are transmuted into group reflection, and the private obscurities of one's own suffering (was it something I did?) are subsumed in broader expression. Even if tradition's moral claims (to the extent that the tradition can speak with a single voice) can often not stand by themselves, the individual might learn something from the group's suffering.

This "something learned" is not a truth or moral message (we don't need suffering for that: I can see that there is imperfection, evil, illness, and death in the world without having to suffer it myself) but the wisdom of others, the knowledge that my experiences partake of a broader human experience. Shared pain is not a lesser pain but different, expressed in a group vocabulary – another genre to be added to the library of emotional strategies.

March 14, 2012

The unlonesome dove flies again!

The vivaciously illustrated journal Paper Darts favored me with two great opportunities: first, a blogpost to wax thoughtful about translation, which starts like this:

For years I have been waiting for a happy throng to corner me in the street demanding my translation secrets. That hasn't happened yet, so I'll share them here uncoerced.

If you want to hear those secrets, go read.

The other opportunity: a corner for the continuation of Avrom Sutzkever's Ode to the Dove in my English translation, with Part IV (here are parts I, II, and III).

Dancer of mine, who are you? Were you given birth by a fiddle?

Under your dance my gardenish body's dug up with a shovel.

She's sick, the little one, lunatic in silvery nightshirt. Not rarely

Swimming away in cold plashing worlds while she's waving.

This is alongside a translation of one of Sutzkever's Diary Poems from 1974.

Far is getting closer. After voyages, adventures,

freestyle on a sheet of paper underneath hawk's shadow,

leave a twin—like day and night—of rhyming lines together

and let them be divided among all your young inheritors.

Enjoy!

March 12, 2012

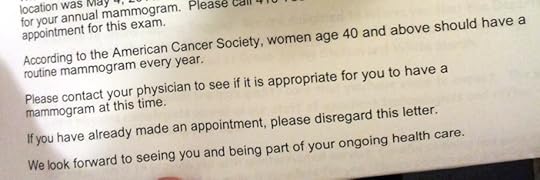

The "annual" mammogram: an enlightening letter

Peruse this letter which a woman of my acquaintance (okay, my wife) recently received. Note the importuning "annual mammogram"

and the official-sounding "According to the American Cancer Society…" (let's not mention the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which recommends every two years, and only for women over 50), juxtaposed with the wishy-washy "Please contact your physician to see if it is appropriate." Which is it? Does the recipient need an annual, or does she need to talk to her physician? Perhaps it would be better to do one or the other: either recommend in the letter straight out, or let her talk the matter over with her doctor?

and the official-sounding "According to the American Cancer Society…" (let's not mention the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which recommends every two years, and only for women over 50), juxtaposed with the wishy-washy "Please contact your physician to see if it is appropriate." Which is it? Does the recipient need an annual, or does she need to talk to her physician? Perhaps it would be better to do one or the other: either recommend in the letter straight out, or let her talk the matter over with her doctor?

Here we have (a) fragmentation of care and advice (different opinions from across the spectrum); (b) confusing, multiple recommendations (ACS vs. USPSTF et al.); and the assumption that "annual" is a default, no matter how artificial and un-evidence-based such an interval is.

March 7, 2012

Purim doggerel 2012

Happy Purim from the Berger Sollods!

אַ פֿרײלעכן פּורים פֿון די בערגער־סאָלאָדס!

חג פורים שמח ממשפחת ברגר-סולוד!

We started off losers but eventually won.

Haman lost his hat

And his ten sons swung –

He's remembered as a pastry.

Can justified war be tasty?

נדמה לפרסים שחג הפורים – טרגדיה.

המן נתלה בעץ (פורחת שקדיה(.

יהודים אוכלים אזוני שר חשוב

ובניהם נשחטים פעם ושוב.

כל נצחון יהודי גורם מפלה עמלקית:

כזה רלטיוויזם בולשיט בשקית.

פֿײדאָאוט. המן הענגט.

אחשוורוש שלאָפֿט. יעדער ייִד פֿאַרברענגט.

מרדכי מוז האָרעװען צו פֿאַרזאָרגן פּרס.

ערגעץ װאַרט װשתּי אין שײנקײט און כּעס.

March 6, 2012

Encouraging autonomy: the movie

Here's the video of my talk at the Berman Institute. The slides are located here.

March 5, 2012

February 28, 2012

Excursus

The idea should be juste

and the mot – mere jus, sauce

to goose the palette.

Thought needs colloquy, let

no one sell you silence, but

neither peddle palaver as gold dust.

Flitting comes natural to the moth,

pointless excurses – are the mote's.

February 27, 2012

From Louisville to Baltimore via Vilna and Tel Aviv

I started studying Yiddish during high school in Louisville, Ky., at the suggestion of my grumpy, thick-spectacled English teacher, Ms. Donsky. Her pedagogical influence was the palpable though unspoken assumption that I was smart but lazy. The first book I tried to read in the language was an overheated novel by Sholem Asch based on the life of Jesus. Later, in college, while others were having sex, starting million-dollar companies, or freezing atoms in the lab, I kept studying Yiddish literature on my own and began writing poetry.

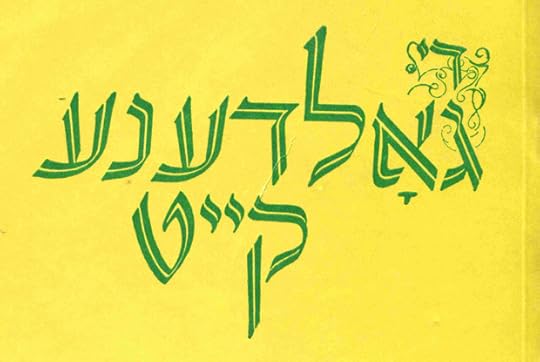

In 1995, I got a ride from my college campus in Pasadena, Calif., to the UCLA library. I don't remember what I first came there for, but I do remember the book I eventually picked up off the shelves with its respectable heft and canary yellow color—a literary journal in Yiddish that almost looked current. The words on the cover, I eventually figured out, were "Di Goldene Keyt," or "The Golden Chain." I eagerly flipped the pages, but enthusiasm could not redeem my limited fluency, and I put the journal back on the shelf.

I am writing this in a house where the dining room table is flanked by an incomplete, tattered, but multicolored set of that same journal, which has become my Yiddish kotel. Its tale, I found out, is anchored by a few names: Avrom Sutzkever. Mordkhe Schaechter. Baltimore, Md.

Read more in Tablet.