Karen Brooks's Blog, page 3

July 28, 2014

Book Review: The Tournament by Matthew Reilly

When I first started reading Matthew Reilly’s, The Tournament, I wasn’t sure I was going to like it, despite the fact it ticked so many interesting fiction boxes. First, it was historica l fiction, which I adore. Second, it was set during the reign of Henry VIII – another positive. Third, it featured a young Elizabeth and her famous tutor, Roger Ascham, so was set on the margins of a period I’ve been researching in depth for over a year now. Lastly, a great deal of the action takes place in Constantinople – modern day Istanbul, a city I loved when I was lucky enough to visit it two years ago. All this was in the novel’s favour. What initially worked against it for me was the extraordinarily modern language of the characters (Henry VIII’s and other characters’ use of the “f” word and other familiar contemporary expletives for example), the fact that though it’s documented that Elizabeth, during her life and reign never went more than 100 miles from London, here she travels to Turkey. I also struggled with the way she was portrayed and her relationship with her father, never mind other characters in the story, which is very much at odds with the character historians and documented records portray. The historical leniency Reilly deployed, or rather, literary license he employed, in terms of clothing and places as well as modes of transport and inter-relationships, all really grated. I am not a purist by any means, but some of the scenes and characters - their dialogue, ideas that just didn’t exist at the time or attitudes that were expressed that were so remote from the era almost had me putting the book down… except I didn’t. Not only did I really like the very original idea of this fictitious chess tournament run by a proud sultan with an axe or scimitar to grind with his foreign royal peers, and putting young Bess in its midst, but Reilly is such a great storyteller, even when I was grinding my teeth and reminding myself that this was a novel first and foremost and forget the history (which is, arguably, a work of fiction anyhow), I was turning the pages and wanting to know what happened. What a craftsman, I kept thinking, what a damn fine lexical craftsman. I forgot my peeves and peevishness and simply enjoyed.

l fiction, which I adore. Second, it was set during the reign of Henry VIII – another positive. Third, it featured a young Elizabeth and her famous tutor, Roger Ascham, so was set on the margins of a period I’ve been researching in depth for over a year now. Lastly, a great deal of the action takes place in Constantinople – modern day Istanbul, a city I loved when I was lucky enough to visit it two years ago. All this was in the novel’s favour. What initially worked against it for me was the extraordinarily modern language of the characters (Henry VIII’s and other characters’ use of the “f” word and other familiar contemporary expletives for example), the fact that though it’s documented that Elizabeth, during her life and reign never went more than 100 miles from London, here she travels to Turkey. I also struggled with the way she was portrayed and her relationship with her father, never mind other characters in the story, which is very much at odds with the character historians and documented records portray. The historical leniency Reilly deployed, or rather, literary license he employed, in terms of clothing and places as well as modes of transport and inter-relationships, all really grated. I am not a purist by any means, but some of the scenes and characters - their dialogue, ideas that just didn’t exist at the time or attitudes that were expressed that were so remote from the era almost had me putting the book down… except I didn’t. Not only did I really like the very original idea of this fictitious chess tournament run by a proud sultan with an axe or scimitar to grind with his foreign royal peers, and putting young Bess in its midst, but Reilly is such a great storyteller, even when I was grinding my teeth and reminding myself that this was a novel first and foremost and forget the history (which is, arguably, a work of fiction anyhow), I was turning the pages and wanting to know what happened. What a craftsman, I kept thinking, what a damn fine lexical craftsman. I forgot my peeves and peevishness and simply enjoyed.

Reilly’s fabulation – that 13-year-old Elizabeth Tudor and her sex-crazed companion (Elise?) accompany Roger Ascham and an English chess champion to Constantinople to compete in a “world” tournament, along with two prudish chaperones – is a coming of age story for the future monarch (and in his Author’s Note, Reilly explains that a great deal of what unfolds is meant to provide psychological context to make sense of decisions Elizabeth makes when she becomes queen – eg, remaining a virgin), as well as a murder mystery.

Travelling to Constantinople poses its own dangers for the English group as they pass through villages, mountains and travel along unfamiliar roads, encountering friendship, hostility and a serious attempt to curtail their journey, but once in the city, the tension between rival religious and ethnic groups makes their trip to Constantinople seem like a walk in the bazaar. When bodies start appearing within the Topkapi Palace, Ascham is asked by the sultan to investigate and so, young Bess is exposed to a slice or slices (excuse the pun, which will become evident once you read the book) of life and a range of people that, with her privileged station, she might never have met.

Smart, assured, and usually one step ahead of the culprit, Ascham not only exposes a corrupt and decadent city and ruler, but finds himself in a race against time to find the killer before he or she claims more victims, including the one person he really cares about.

Fast-paced, able to balance action with more measured scenes and make chess fascinating even for non-players, Reilly has crafted an inventive and fun take on Tudor history. Far from putting it down, I was forever picking it up and ended up really enjoying this rollicking tale, even if it didn’t always satisfy my non-purist historical fiction desires. I give it 3.5 stars. But sheesh, I give Reilly 4.5 for his fictive chutzpah. Wish I had it!

July 22, 2014

Book Review: An Air of Treason by P.F. Chisolm

At first, I didn’t think I was going to enjoy this book and I blamed that feeling on the fact I’d picked up the sixth book in a series. However, after a few chapters, I fell into the story – pa rtly helped because many of the characters are based on actual historical figures, so I already had a sense of who they were and the real-life roles they had, but also because the tale itself is so engaging.

rtly helped because many of the characters are based on actual historical figures, so I already had a sense of who they were and the real-life roles they had, but also because the tale itself is so engaging.

Chisolm does a marvellous job of bringing to life the latter years of Elizabeth the First’s reign and the rise of her favourite, the Earl of Essex, and the various politicking that went on. Her lead character is Sir Robert Carey, a courtier and cousin of the queen who, in this instalment is in Oxford where the queen is on progress. Determined to wrest from her Majesty’s tight fingers wages he’s owed for being Deputy Warden of the West march with Scotland, Carey converges on Oxford as well. Instead of getting his fee, Carey is given a task – to find out what really happened to the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley’s first wife, Amy Robsart, thirty years earlier.

The death of Amy has always been considered mysterious and cast aspersions not only on the queen but her favourite, Leicester, and is long read (and hotly debated) as one of the reasons Queen Elizabeth didn’t marry him. Effectively a cold case, Carey begins his investigation, but all too quickly discovers there are those who don’t want the truth to come out. Soon, Carey is in as much danger as it seems young Amy was as well…

Parallel to this story is that of Carey’s trusted man, Sergeant Dodd, who coming to join his master, is waylaid in violent circumstances and held captive. It’s not only the mystery of Amy’s death Carey has to solve, but of Dodd’s disappearance too. Carey must find his man before it’s too late – for Dodd, Carey and the queen.

This ended up being a rollicking good read. Historically accurate with lovely fictive embellishes, it should please lovers of history and those after a page-turning murder-mystery. I liked this so much, I went and bought the first few Carey adventures and cannot wait to read them

Book Review: The Constant Princess by Philippa Gregory

I thoroughly enjoyed this revisioning of the early years of Catalina of Spain who would later be known as Catherine of Aragon, the long-suffering first wife of King Henry VIII. An often silent and very religious presence in many fictive accounts, a woman who stood by Henry for over twenty-seven years before her marriage to him was ended in tumultuous circumstances, resulting in not just the rendering of her only living child to Henry, Mary, a bastard, but the over-turning of the Catholic faith in England, Catherine as a person remains an unknown quantity. She also tends to hover in the margins when it comes to Henry’s reign and his other wives and the fate that befell them, especially Anne Boleyn, the women who took Catherine’s throne and husband and whose daughter went on to become the “Virgin Queen”, Elizabeth 1st.

often silent and very religious presence in many fictive accounts, a woman who stood by Henry for over twenty-seven years before her marriage to him was ended in tumultuous circumstances, resulting in not just the rendering of her only living child to Henry, Mary, a bastard, but the over-turning of the Catholic faith in England, Catherine as a person remains an unknown quantity. She also tends to hover in the margins when it comes to Henry’s reign and his other wives and the fate that befell them, especially Anne Boleyn, the women who took Catherine’s throne and husband and whose daughter went on to become the “Virgin Queen”, Elizabeth 1st.

Well, Gregory sets about to change that, presenting readers with a delightful account of Catherine’s unconventional childhood, as the much-loved younger daughter of Isabelle and Philip of Spain. Possessed of bellicose parents whose ambitions were to conquer and claim lands and people, Catalina’s girlhood was spent in military encampments, always on the move until, finally, her parents settled. Though they tried to destroy the Moors and suborn them to their faith, they end up adopting many of the habits of those they try to oppress. Catalina carries an appreciation for the skills, hygiene, knowledge and artistry of the Moors and Islam her entire life.

Revelling in her privilege as a princess – the Infanta – Catalina is also raised to understand she is destined to be the Princess of Wales and eventually Queen of England and it is to Arthur, eldest son of Henry Tudor and Elizabeth of England that she is betrothed. But this is no love match for, like many young noble women, Catalina is but a pawn in a long political game.

For those of you who don’t know the history of Catherine and Arthur and Henry – please read no further. For those of you who do, the book remains true to events, but offers readers of the period something more.

Arthur tragically dies after only a brief few months of marriage, and Catherine eventually becomes the wife of his younger brother, Henry. What Gregory does, is present the relationship between Catherine and Arthur in an interesting light – very different to other accounts both historical and fictive (though, as I inferred above, in many ways this period of Catherine’s life (let alone the figure of Arthur) is barely addressed by other writers except as a footnote).

After Arthur dies, Catherine loses her position at court and, in many ways, her identity as well and in a ruthless way determines to have both restored. From this point on in the novel, it could have been subtitled: “I Wanna Marry Harry”, so single of purpose was the young Infanta.

The story of Catherine’s patience, of the way she deals with hostile forces at court (mainly Henry’s grandmother and later, father) and how she eventually triumphs is wonderfully done.

Segueing from third person to first person point of view, we get that omniscient narration of events as well as personal and sometimes heart-breaking accounts. There were points at which the first-person parts grew repetitive and a bit tedious, but more often they offered insights into the emotional and psychological energy and passion of this remarkable woman.

Henry is also presented in a different light – as the selfish, bombastic and indulged king historians have long known he was. Playing to his strengths and indulging his weaknesses (of which there are so many), pandering to her husband to get her own way, Catherine is presented as a strategist par excellence but one with a heart and a conflicted soul.

Capable, shrewd, loving and forgiving, one of the most affecting things about the novel is those of us familiar with her story know how it will end. Gregory does well to finish the book as she does and leave readers with a sense of satisfaction rather than desperation for the woman at its centre. You cannot help but love Catherine and loathe the forces that dealt her such a cruel blow and the people that ensured where and when it would land.

A fabulous read for lovers of history and a great story about a woman of substance.

July 7, 2014

Book Review: Snow White Must Die

Knowing how much I enjoy crime novels, a friend (thank you, Cornelia!) recommended to me that I try Nelle Neuhaus and suggested the disturbingly titled Snow White Must Die as an introduction to her work. Opening with an intriguing prologue, it’s when the novel proper starts that I was really hooked. Snow Must Die centres on Tobias Sartorius, who after serving eleven years in prison for the murder of two lovely young girls, returns to his home and the place where the crimes took place. While there are those who believe in Tobias’ protests of innocence and point to the fact he was charged on the basis of circumstantial evidence alone, and have remained loyal, there are many more who are not only out for revenge and bitter and angry, but are harbouring secrets that Tobias’ presence among them and the memories he threatens to disturb.

Finding his home and the town a shadow of its former self, Tobias is rattled. When attacks upon first his family and then those who would aid him occur, Tobias and the police called to investigate, understand that dark forces and people with deadly motives are operating.

Early in the story, Pia Kirchhoff and her boss, DS Oliver Von Bodenstein are brought in to investigate the brutal assault of a 51-year-old woman. When they understand she is linked to Tobias, they find they are asking more questions than they are receiving answers and what made sense to police and detectives over ten years ago, no longer holds true. Keen to reopen Tobias’ case, there is at first no reason, but it isn’t long before one is found…

The town in which the novel is set, Altenhain in Germany is as much a character as the barflies that take up space in the main diner. Once prosperous, it teeters on ruin and decay, functioning as a metaphor for what it’s both facilitated and hidden for over a decade.

Filled with interesting characters with credible back stories and complex and rich personal lives, Snow White Must Die doesn’t only focus on crime and criminals but on the impact of violence upon individuals and families and the influence being in the police force has on relationships as well.

Like Tobias, his father and the young Goth, Aemlia, and her friend, Theis, the police personnel, Pia and Oliver, are flawed, passionate and loyal, and the tensions in their professional and personal relationships simmer on the page.

Fast-paced, ofttimes violent, the novel is unrelenting in exposing the parochial attitudes that can afflict certain groups with pecuniary and other interests to protect and no moral centre. This is where Tobias and the friends he makes as well as Pia and Oliver come into their strengths. Each in their own way provides an ethical touchstone for events, even when their actions do not always accord with the collective moral compass – but then their own notions of right and wrong do and consequences ensue.

Towards the end, the pace staggers to a crawl and while much of what occurs in the last few pages is essential to the narrative, and great to read, there is a sense in which it goes on a tad long. Not that I minded because I really enjoyed the book. Though I did wonder just how much more poor Tobias could take!

As it is, cannot wait to read the next one of Neuhuas’ books I’ve bought: Big Bad Wolf.

July 6, 2014

Book Review: The Miniaturist by Jesse Burton

This was a hauntingly lovely, deeply sad book that remained with me long after I finished it.

Set in the Golden Age of The Netherlands, in Amsterdam in 1868, The Miniaturist tells the story of young Nelle (Petronella) Oortman who arrives on the doorstep of her new husband’s house and, as she crosses the threshold of this tidy, well-ordered home, steps into another world. Her husband, the wealthy, charming Johannes Brandt, lives in a place far removed from Nelle’s sheltered and rather Godly life in the country with her mother and younger siblings. In Amsterdam, the heart of trade and merchant-living in Europe, it’s guilders before God, and sweet Nelle finds the surface splendour and prim facades disguise deeper and curious as well as highly hypocritical undercurrents.

Swept into a life in which she feels she has no place, she is forced to deal with Johannes demanding sister, Marin, whose aloofness is countered only by her maid, Cornelia, who appears to Nelle to not understand the boundaries between employer and servant. A situation that’s made more puzzling by the presence of the coffee-skinned Otto, whose kindness and humanity is, when he leaves the house, disregarded by locals as his exoticness takes over, earning cruel barbs and awful assumptions. Nelle is overwhelmed by all this and prays that love will smooth her path, especially when her husband appears to neglect her.

Then, one day, Johannes buys her a beautiful dolls’-house. It’s a huge cabinet - a replica of their place – that he invites her to furnish. Reluctant at first, Nelle acquiesces and hires the services of a superb miniaturist. But when the pieces she commissions are not only exceptionally fulfilled, but rendered in exquisite and intimate detail, she wonders what is going on. They are so life-like, prophetic, full of significance… Alarmed, she eventually reads the pieces and the messages that accompany them as signs of a life she should either aspire to or as a warning of what’s to come…

Part mystery, part lyrical portrayal of families and relationships and the complex webs we weave and in which we entrap ourselves and others, The Miniaturist is also an examination of social structures and the lengths people will go to in order to protect their place, their role, conceal their secrets, maintain what to some might be lies but to others are the veneers we must never allow to crack. Burton’s understanding and portrayal of the repressed but seething society of Amsterdam of this time is stunning. Her use of the doll’s house as an analogy for what goes on behind other closed doors, of how we can be fashioned in another’s image, moulded to an ideal, is very clever. I remember seeing these dolls’ houses at the Rikjs Museum when I lived in The Netherlands and thought them amazing. Their use here is unique and eerie. Unlike the life-like dolls made for Nelle and which she places inside her doll’s house, the characters in Burton’s real Dutch houses that abut each other, line the canals and share the repressive joys of community, come to life in ways that are surprising, distressing, utterly gripping and heart-wrenching.

I found this book hard to put down and am not surprised by the accolades it has received. Terrific.

Book Review: The Silkworm by Robert Galbraith

After reading Cuckoo’s Calling, I couldn’t wait for the next installment in the life and foibles of the wonderfully named ex Special Branch Operative, PI Cormoran Strike and his eager and quite adorable side-kick, Robin Ellacourt.

eager and quite adorable side-kick, Robin Ellacourt.

Well, The Silkworm didn’t disappoint. It opens with Cormoran dealing with the influx of clients (wealthy) he’s attracted as a consequence of the fame his last case brought him – tracking down infidelities, finding proof of betrayal, things that he does because they keep the till ticking over but are not very fulfilling. When he’s asked by a worn down and quite ordinary woman who arouses his sympathy and protective streak to track down her missing author husband, Owen Quine, and with a fairly obscure promise of payment, Cormoran (much to his surprise) agrees.

Flung into the literary world where egos reign and revenge is lexically bitter-sweet (the adage, don’t piss of a writer, you may well appear in his or her next book rings so true here), Strike cannot find the narcissistic and selfish Quine, though he does discover that the man has written a book set to turn the publishing world upside down. Taking the notion of the “poison pen” literally, Quine has written a terrible expose of all those who ever wronged him in his long and with one exception, not very successful career.

Learning the limits of this unattractive (in terms of personality) and flamboyant writer, both through his unpublished manuscript and anecdotes from those who knew him, Cormoran also discovers many people with a motive to kill him. When a horrendously brutalised body is discovered, what was once a sick literary fantasy fast becomes a shocking reality and Cormoran understands he’s dealing with a psychopath who will do anything to protect their identity…

Wonderfully paced, filled with fabulously drawn characters who are flawed, angst-ridden, funny, acerbic and also naive, The Silkworm is a terrific sequel to Cuckoo’s Calling. While Quine’s book is filled with metaphor and allusion based around Pilgrim’s Progress, there’s a sense in which Strike undergoes his own progress – him and Robin who is keener than ever to establish her credentials as not just Strike’s PA, but a professional partner. Encountering the bizarre people who populate the literary landscape, fiendish personalities and some very gory and weird scenarios, Strike has to deal with egos, intellect and lexical word games, dissembling and lies (or are they simply versions of the truth?) in order to uncover the killer.

As in the first novel, Strike’s personal life and his awareness of own weaknesses feature and this makes him such an attractive character. His self-reflections, his understanding that he occasionally uses people and the way this pricks his conscience, are beautifully drawn. You feel Strike’s physical and emotional pain, but also his stoicness in the face of forces beyond his control. Thus, you engage with him even when you don’t necessarily approve of his decisions – how can you not when the most critical judge of Strike’s choices is himself?

Robin really comes into her own in this novel as her personal life throws up questions and challenges and she’s forced to make some clear cut choices. You can feel the relationship between her and Strike grow – but it’s also organic, respectful and extremely gratifying, even when the lines of communication fail.

Found this book very hard to put down – clever, eminently readable, and for a genre that’s well trod, highly original as well.

Book Review: Dancing on Knives by Kate Forsyth

Whatever I was expecting when I picked up this novel, Dancing on Knives, it was not what Kate Forsyth delivered. Having said that, the story of Sara Sanchez, a young woma n tormented by loss, longing, and a hugely dysfunctional family dominated by her egotistical, passionate and bullying artist father, Augusto Sanchez, is a study in how the mind and body can become a far worse prison than four walls ever can. This is a novel about betrayal, choices, trust, anger, grief and healing, one that lingers long after completion.

n tormented by loss, longing, and a hugely dysfunctional family dominated by her egotistical, passionate and bullying artist father, Augusto Sanchez, is a study in how the mind and body can become a far worse prison than four walls ever can. This is a novel about betrayal, choices, trust, anger, grief and healing, one that lingers long after completion.

Suffering from panic attacks and an anxiety disorder (that’s never named but heart-wrenchingly described), Sara tries to keep herself and what remains of her family together – her difficult father, surly older brother, the twins, and her resentful step-sister. Unable to leave the property that defines her life past and present, when her father disappears one stormy night, Sara is forced to confront not only her crippling fears, but the family history and secrets that have formed her, the present that defines her and the future that awaits her if she chooses.

The tale of Sara and the Sanchez family slowly unfolds, often told through vignettes of Sara’s childhood and recollections of the Sanchez family before she was born and the Spanish traditions her grandmother and father tried to keep alive, before being interrupted by events in the present as the search for her father and the wreckage his presence has left are revealed. Food, stories and rituals play a big role in this narrative, becoming anchoring points and it’s through these that Sara often escapes her bleak reality – these and the Tarot cards she sometimes reads as way of containing and preparing for what might happen next.

The mystery of Augusto and his fate, while it sets the action, mostly plays second fiddle to the mystery of Sara’s state of mind and her gradual, painful healing.

This is not a happy tale, but it is haunting and like all Forsyth’s works, beautifully written. For those anticipating another Bitter Greens, this book isn’t it and the metaphor of the little mermaid is used powerfully but in ways that “speak” (excuse the pun) to the underlying meanings of silence – it’s constraints, power and its punishing consequences. After finishing this, I was sad for days, angry at the forces within and without that can shape who we become and how our choices can be framed and limited by those others make, and though it left me frustrated and strangely dissatisfied, the beauty and truth of this tale is undeniable.

The Blue Mile by Kim Kelly

The Blue Mile is quite simply an extraordinary book. I absolutely loved it and, once I’d grown accustomed to its very original style, the quirkiness and authenticity of the language, as well as the way the tale is told, found it impossible to put down.

Set in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Depression-era Sydney, the book is narrated from two points of view: that of Eoghan O’Keenan, an Irish-Australian man eking out an existence in the slums of Chippendale, Sydney, and Olivia Greene, a lovely young designer who dreams of opening a couture’s salon in Paris. The Blue Mile is at once a simply beautiful love story, a homage to a largely forgotten time in Sydney, a story about the way politics impacts upon real lives, and a treatise on class and religious differences.

Set in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Depression-era Sydney, the book is narrated from two points of view: that of Eoghan O’Keenan, an Irish-Australian man eking out an existence in the slums of Chippendale, Sydney, and Olivia Greene, a lovely young designer who dreams of opening a couture’s salon in Paris. The Blue Mile is at once a simply beautiful love story, a homage to a largely forgotten time in Sydney, a story about the way politics impacts upon real lives, and a treatise on class and religious differences.

Seguing from Eoghan (Yo-Yo’s) voice and Olivia’s, we see the close of the 1920s through their very different eyes. Yo-Yo offers a masculine voice of desperation, ideals and firm work and religious ethics all of which have him fleeing the house in which he grew up, a house which offers him nothing but a bleak and violent future. A man of high principles and gallantry despite (or perhaps because of) his working class origins and abusive upbringing, Yo-Yo takes his seven year old sister, the adorable, Agnes (Aggie) with him, determined to give her what he never had: love, stability and a future.

Running counter to Eoghan’s dark tale is Olivia’s feminine and whimsical dreams, ones fostered by her hard-working mother who instills in Olivia an unusual spirit of independence and a belief in the power of dreams if only you work towards them. Olivia is the child of a dissolute British aristocrat who, after divorce, ships his ex-wife and daughter off to the antipodes without another thought. Only mildly bitter, Ollie is a kind and talented soul who though she longs for change, also fears its consequences. Determined to achieve her dreams and on her own, she eschews her mother’s offers of help and, later of relocation, and forges ahead, earning a reputation some covet and others envy.

But it’s when fate brings Eoghan and Ollie together and steers them onto a rocky and unpredictable path that both of them have to make difficult choices, choices that run counter to what their upbringings, dreams, class, parents and God have taught them to expect. Their stories intertwine and collide with heart-breaking, uplifting and calamitous consequences – for Ollie, Eoghan, Aggie and those who love and care about them.

I don’t want to say too much more lest I spoil this unforgettable tale except that the way the era is evoked is utterly magical. The phatic language, the everyday patois of the working, middle and upper classes gives the novel such authenticity and veracity as does the sense of time and place. The way Kelly understands and uses history, not in a boring didactic way but to make the story sing is marvellous. She makes the shape of a hat, a brooch, or the collar of a shirt signify an era and those who not only lived but worked through it in ways that are at once clever and lyrical. As the characters walk the streets of Sydney, so too the city comes alive for the reader in all its ugly glory and promise. The Harbour Bridge which, as the book opens, is incomplete is as much a character as the city, but it’s also a metaphor for the events in the book: for the span of time, for hopes, imaginings, and livelihoods built, shattered and salvaged. It’s a sign of union and unions, of a city on the cusp of transformation, of a new era about to be ushered in. It’s also signifies the journey the two central characters make – from opposite sides in every way to some kind of possible or impossible meeting.

This juncture, like that of the bridge, is not without battles – emotional, financial, religious and other. And it’s through these that the heart of the book (and the folk that live in its pages) come alive and beats at a frantic pace making it impossible to put down lest you miss one single moment.

A gem of a book that will captivate lovers of history, romance, politics and so many others things besides. It surprised me in the most wonderful of ways – it literally took my breath away and I cannot wait to read more of Kelly’s work. Cannot recommend this novel highly enough. It is stunning.

June 10, 2014

Book Review: The Many Lives and Secret Sorrows of Josephine by Sandra Gullard

Recommended to me by a girlfriend with impeccable reading taste, I was still, for some reason, somewhat reluctant to read this book. I knew very little (or cared – I am ashamed t o admit) about Josephine or Napoleon (apart from “not tonight, Josephine” – I don’t even know what the context for that is!) and felt there were too many other figures from history that I wanted to learn about and experience through fiction or non-fiction to invest in a three book series. Well… excuse me while I go and eat my words.

o admit) about Josephine or Napoleon (apart from “not tonight, Josephine” – I don’t even know what the context for that is!) and felt there were too many other figures from history that I wanted to learn about and experience through fiction or non-fiction to invest in a three book series. Well… excuse me while I go and eat my words.

From the moment I picked up this book, I was hooked. Written in the first person (it’s presented as though it’s Josephine’s diary), it commences when Josephine is 14-years-old and then called Rose, the daughter of slightly impoverished landed gentry on the island of Martinique. Of Creole heritage, Rose has dreams and these are fuelled when a fortune teller informs her she will be a queen one day.

When her younger sister dies, Rose becomes a substitute bride and undergoes the long sea voyage to France to take up her position as a minor noblewoman as the wife of Alexandre de Beauharnais. But life as Alexandre’s wife is not what Rose expected and as she bears children and is given entrée into Parisian society, she also has a front seat to her husband’s infidelities and indifference and the French Revolution – the latter which unfolds swiftly as the Terror descends. The Ancien Regime is collapsing, allegiances shift daily, and Rose has to find a means to protect her children, her greater family and friends, and above all herself.

Beautifully written and impeccably researched, I couldn’t put this book down. Gullard spent ten years researching this trilogy (of which this is the first book) and it shows, but not in a didactic way. Martinique and the customs and culture of the indigenous and their French colonisers, and their differences to their France-based counterparts is wonderfully realised. As we see, smell and are inculcated into the island culture, so too, through Josephine’s naïve and fresh eyes, we see France and Paris. We enjoy the beauty, the sophistication, the fashion and habits, but also deplore the filth, poverty and later, blood and cruelty. Some events take place “off-stage” and those that don’t are given the personal touch through being viewed and oft-times experienced by Josephine or a close friend. The fear and concern, the drop in fortunes, the confusion as titles change, even days of the week and festivities are renamed and those once lauded as heroes of the revolution are killed as traitors is palpable.

Through all this, Josephine, as a woman, mother, “citoyen”, shines. Her care for others, her love for her children and theirs for her; the lengths she will go to in order that justice is served, are heart-wrenching and brave. As a reader, you are filled with wonder for this woman. It’s only towards the end of book that the ambitious Napoleon enters the story and I loved that he remains a peripheral character, even as he woos her, for this is Josephine’s tale and it is her voice we hear.

The footnotes that accompanied my kindle version were terrific and enhanced my reading pleasure. At first I thought they might encumber the story, but they don’t. They are like discovering a chocolate under the pillow as you open the reference, read and appreciate the way a fact has been woven into the narrative – seamlessly, always.

Gullard is a masterful storyteller who brings Josephine and the events in which she finds herself to life – better still, she engages the reader’s heart and head and in doing so creates an unforgettable interpretation of a remarkable woman and time.

For lovers of great fiction, historical novels interwoven with fact, love-stories and those that recapture women’s experiences and give them voice, I cannot recommend this highly enough.

June 9, 2014

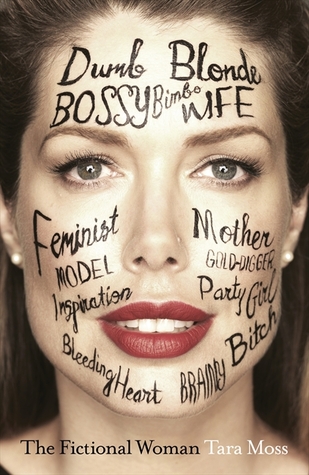

Book Review: The Fictional Woman by Tara Moss

One of the most thoughtful and erudite books on the female experience I have read in a long time. Rather than being exclusive or looking to apportion blame, Moss tackles the sometimes divisive subject of feminism and females through inclusivity and such a depth of understanding of culture, society and the various forces that shape us all.

Part memoir, part treatise on the way women are labelled and stereotyped and then read accordingly (and men as well), Moss patiently and cleverly deconstructs a range of assumptions, using a mixture of theory, excellent research, personal experience and anecdotes.

Commencing with herself as subject, she then goes on to explain her objectification – as model, a body, a survivor and even as a writer. Having entered the fashion industry at an early age, her desire to be a professional writer was delayed but when she finally did have her first novel published, she found that the “tag” of model and the negative (and at times crushing) social and cultural assumptions of this profession haunted her aspirations. Not one to let this deter her, Moss unpacks her slow acceptance by the literary scene with humour and stoicism, and uses it as a case study through which to examine the ways in which women are constructed in mainstream culture and why this happens and, more importantly, why it’s essential to critically examine these reductive representations and understand the limitations they impose on subjectivity and female agency.

Lucid, entertaining and always engaging, Moss briefly considers the female experience through history, thus providing a context before discussing topics such as “gender wars”, male and female beauty, the notion of the invisible and visible woman (the latter through marketing and advertising) as well as how the social and cultural roles of mother and father, among many others, impact, define and either elevate or reduce us.

Moss gently but very persuasively argues that while we have a tendency in society to target individual women (and sometimes men) for harsh criticism and worse, we’re actually failing to identify and thus change the greater forces that work to uphold and restrict women’s agency. Complicit in patriarchal culture we might be, but that doesn’t mean we cannot step outside its constraints or work to change it. Her message is strong and beautifully and succinctly delivered. Her chapter on “The Feminist” had me cheering.

Moss also tackles why we need to deconstruct and critically think about the images that bombard us, the labels that we so readily bestow. She discusses the value we assign to women’s appearances and how these are also connected to morality, redundancy, conformity and a great many other emotional and psychological hurdles and burdens. Citing statistics and a great many studies, she demonstrates the lack of female representation (and diversity) in everything from parliament, politics generally, Hollywood, workplaces, education, role-models, to the dearth of meaningful representation of women of all ages, shapes, sizes and talents, in culture generally. Women are still rendered as object (often domesticated) and the power of our bodies lies mostly in their ability to arouse desire or open wallets – in other words, female bodies are most often used to sell – even the idea of competition to each other. But what Moss also investigates are the ideas our bodies both sell and perpetuate in the limited representations available and what the labels thus assigned do to our standing and understanding or ourselves and others – at the individual, family, relationship, social and political level.

The tropes of maiden, mother and crone as well as “Madonna” and “Whore” enjoy a great deal of scrutiny throughout the book, and the power they have had historically, socially and culturally to shape an understanding of women – through popular culture and beyond – is explored.

A powerful book but without being preachy, I could not put this down. If I was still lecturing at university, I would place it on my courses. As it is, I can only recommend that people of all ages, both sexes, read it. It’s an enriching, thought-provoking experience that I for one am so glad I had and will do so again.