Michelle Ule's Blog, page 89

October 25, 2013

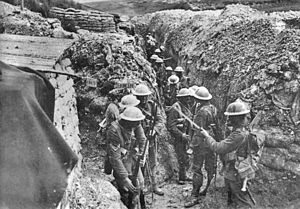

The Trenches

We headed to the western front to see the land and explore the trenches.

We’d visited museum examples of World War I trenches in the Auckland (New Zealand) War Memorial Museum; at the Musée de l’Armé in Paris; at the Imperial War Museum in London and I’d stood in one in downtown Indianapolis’ World War Memorial just last month.

It’s the miserable trench warfare people think of when you mention World War I.

The Allies and the Axis powers built 500 miles of zigzagging trenches all the way from the English Channel to the foothills of Switzerland. It represented stalemate as they stared at each other, often through periscopes, across a no-man’s land of barbed wire and land mines.

Absolutely miserable

Basically dug eight or so feet into the ground, trenches provided a cover of-sorts in a war that didn’t have much in the way of airpower. Planes in 1914-1918 were primarily used as reconnaissance–to know where things were–rather than as weapons. Airplanes may have had machine guns by the end of the war, but bombing capabilities were limited.

Instead, the men dug into the ground. When it began to rain, they put down “duck board” to walk on. Latrines had to be dug into the walls of their trenches. Rats and other vermin, particularly lice, thrived in the conditions.

Many soldiers came down with “trench foot,” a disease resulting from spending so much time in wet socks and boots.

The smell was atrocious and, really, they were simply living in open holes to the sky.

The smell was atrocious and, really, they were simply living in open holes to the sky.

“Going over the top,” meant clambering out of the deep furrows carrying weapons and heavy packs into the nightmare of barbed wire and machine gunfire.

Horrific.

100 years of rain and silt has filled in most of the trenches save for those specifically set aside for tourists. We did not tour any intact trenches, instead, we wandered among the rumpled earth of the Somme, seeing the remaining lines of where men once burrowed into the ground in the hopes of staying alive another day.

At the South African memorial site, our guide could showed us trench remains.

As the rain pattered down, we hurried through the trees to curious indentations in the ground, more like the humps left behind by giant moles–which I suppose they were. The rainwater puddled in the water, just as it had 100 years ago.

As the rain pattered down, we hurried through the trees to curious indentations in the ground, more like the humps left behind by giant moles–which I suppose they were. The rainwater puddled in the water, just as it had 100 years ago.

I wore tennis shoes that day, which quickly became soaked, but unlike the men who battled trench foot all those years ago, I knew I’d be in dry shoes and warm clothes by the end of the day.

My husband wore his brand new trench coat–a specific type of rain coat made of water-resistant gabardine designed and created by the Burberry Company and so loved by the officers who wore it, it became a fashion statement after the war.

He was dry all day.

Further down the road, our guide took us off into the woods to show us an area he had found while exploring. “These were German trenches,” he explained, sketching with his hand where each side had lined up. “They’re surrounded with barbed wire now because it’s considered an archaeological site. Teams will come in and excavate. We can just look.”

If you squint you can see the rows of indentations that marked the trench lines. Notice how the trees grow up from different levels of soil. The trees are all less than 99 years old, of course.

If you squint you can see the rows of indentations that marked the trench lines. Notice how the trees grow up from different levels of soil. The trees are all less than 99 years old, of course.

If you’d like to see and learn more about just what happened in the Somme trenches, see this video on Youtube.

The trenches were lengthy and connected to the back lines. Sometimes there would be as many as 12 different trenches to overrun once soldiers survived the dash across no man’s land.

Absolutely nightmarish.

The Germans perfected trench building and by 1918 had shored up the earthen sides with cement and dug up to 40 feet underground. They had hospitals, dry beds, and even a train system to move artillery to their front lines.

The British had dirt dug outs and never-ending rain.

Really, as I read G. J. Meyer’s A World Undone and other books about World War I, I’m amazed the Germans did not win the war. The quality of their trenches and pillboxes surely should have given them the edge in battle.

Aerial view Loos-Hulluch trench system July 1917

Meyer thinks the Americans entry in the war in 1918 made the difference.Our guide was not so sure.

Regardless, it was sobering to contemplate.

What do you know about World War I trenches?

Tweetables

WWI trenches are still there Click to Tweet

The misery of WWI trenches, even today Click to Tweet

What were WWI trenches like? Click to Tweet

The post The Trenches appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

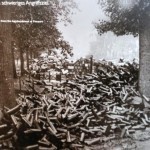

October 22, 2013

Wandering the Somme

We went wandering the Somme battlefields last week, looking for a sense of what life was like there 99 years ago.

When you say World War I, people immediately think of the trenches and the dreadful killing machines.

They weren’t there, but their memory echoed through the beautiful landscape and as our guide recounted miserable story after dreadful event, our spirits sank like the doughboys all those years ago into the mud of Somme despair.

The last victims of the Great War died only five years ago. They stumbled upon a canister in the ground, pulled it up and it broke apart releasing mustard gas.

Mustard gas goes right through the skin.

Four people died.

Farmers in the Somme area, and probably elsewhere, are still finding shells left over from the Great War. The artillery munitions probably aren’t going to blow up, but the gas shells must be treated carefully.

When a farmer encounters one in his field, he puts out a white flag much like those we use in the US for irrigation line markers. He dones a pair of special gloves and carefully moves the shell to the side of the field.

A contemporary photo of used shells

If you look closely at the base of the crucifix, you’ll see four or so tubes that look similar to giant zucchini.

They’re live World War I shells.

When the people traveling with us got out to take their picture, one Australian reached to touch a shell. Our guide shrieked, “It’s still dangerous.”

We all shuddered.

Once a month the French army travels through the area and picks up shells, still potentially dangerous, from World War I.

Wandering the Somme valley, we encountered plowed fields and those finishing their harvest. Periodically, the fields were separated by groves of Poplar trees.

“No man’s land,” the French guide grunted. “So many shells are in the ground, it cannot safely be plowed. So they grow Poplar trees which can be harvested and made into paper without fear of unexploded ordinance.”

“What happened to the people who lived in these villages?” I asked.

“They fled when the Germans came and returned at the end of the war.”

I couldn’t fathom it. “Why would they come back here? You couldn’t exactly send your children out to play with all the unexploded bombs.”

Our guide, whose family lived through the two wars in central France, lectured me about how people love their land and want to return. They did what they needed to survive.

I can’t imagine living in a place so lead infested you can’t drink the water from the tap nor eat the fish from the river, much less fear touching an old piece of metal, lest it kill you with mustard gas.

The plows turned up five bodies in a field last year.

“Bones are lighter than the soil,” our guide explained, “and they are pushed to the surface as the land settles.”

They identified them as Canadians by the scraps of uniform clinging to the bones, “and because the officer had a pistol. Only officers could carry guns–that’s how we knew he was an officer. They carried them to use against soldiers who did not want to fight.”

Many of the battles took place during the rainy season. The mud in that part of France is dense and liquid, almost like quicksand.

Wandering the Somme was so dangerous, soldiers carried lariats of rope on patrol for when they slipped into the mud. Stories were told of the recoil from a large gun sinking it so far into the mud, they had to dig out the heavy artillery before they could resume firing.

Many soldiers simply took a wrong step and drowned in the liquid dirt.

Makes you wonder if it was preferable to being shot by your commanding officer?

My husband explained that when the Commonwealth countries agreed to send soldiers to the British Army, they would not allow their soldiers under British command unless a promise was made officer’s pistols would not be turned against their men.

The British were desperate and agreed, which one hopes brought a measure of sanity to a war that defies understanding.

Wandering the Somme, looking at munitions made 100 years ago, and contemplating the danger of mud, made for a sobering afternoon. And yet, it was the least we could to honor all those young lives destroyed so long ago.

Would you be tempted to pick up a shell in a war zone?

Tweetables

95 years after WWI, mustard gas is still a danger Click to Tweet

Gas and mud: Somme dangers live on Click to Tweet

Wandering the Somme with WWI in mind Click to Tweet

For more photos from my trip, visit my Pinterest board Wandering the Somme

The post Wandering the Somme appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

October 18, 2013

A Trip to the Western Front

This is a photograph of a young German soldier engaged in the Battle of the Somme, 1916. He wears a helmet, so the photo is from late in 1916. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Western Front was the site of the worst fighting of the First World War. It refers to Germany’s western front, even though it’s located in southern Belgium and northeastern France.

A fertile farmland that rolls to the English Channel, the western front remains scarred by the activities of 100 years ago.

My husband and I were there on Monday.

I’m writing a novel set during World War I and the final third of the book takes place in France. My heroine and her journalist father take a trip to the Somme River area, and I wanted to see what it looks like.

The western front is deceptive in appearance.

Our French guide began the tour at Lochnagar Crater Memorial, the site of an explosion that, at the time, was the largest and loudest one ever heard. Reportedly felt as far away as London (250 miles), it marked the beginning of the June 1916 battle.

The crater is enormous.

It sits on a rise that overlooks the pastoral countryside. In October, the fields were newly plowed or still green with the end of summer crops. Clumps of trees and stone farm houses dot the landscape. On that rainy day, it felt sleepy and tranquil. Our guide waved his arm: “1.2 million people died in this area over a two year period.”

1.2 million casualties is a number difficult to contemplate.

It made me think of the battle of Helm’s Deep scene in the movie The Two Towers, when (though computer animated for the screen) soldiers filled the scenery for as far as you could see.

It must have been like that on the Somme.

Except the soldiers were dug into trenches zig-zagging across the landscape with a “no man’s land” covered in barbed wire.

Like the Cliffs of Dover, some sixty miles away, the coastal farming areas of France and Belgium sit on top of chalk limestone. The guide pointed out plowed fields littered with white flakes.

Like the Cliffs of Dover, some sixty miles away, the coastal farming areas of France and Belgium sit on top of chalk limestone. The guide pointed out plowed fields littered with white flakes.

“Everywhere you see white chalk in the ground, you know that was a battlefield. So many bullets flew, they stirred up the chalk which all these years later, still comes to the surface.”

The newly-improved machine guns manned by the Germans swept the no man’s land with a wind of bullets so thick, bodies were obliterated and groves of trees splintered. The bullets contained lead and so much was fired and left in the ground, the water in the town of Pozières is contaminated. Residents cannot drink tap water. Fish in the Sommes River cannot be eaten.

“They estimate it will be 800 years until the lead has fully leached away and the land will be as it was before the war.”

The soil, of course, is very fertile because of all the iron leftover from the spilt blood–100 years ago.

Our French guide hates Germans.

”How would you feel if they invaded your land? We did not invade their land, yet they came here and murdered our grandfathers and raped our grandmothers. I will never have a German in my car.”

He added his was not an opinion shared by all in the European Union.

Indeed, universities on the continent do not call the “Great War,” World War I.

“In Germany professors call it the ‘European Civil War.’ In France we consider is a very long war with a long cease fire.”

World War II was caused by unresolved issues from the first war, a generation before.

“Somme” comes from the Celtic word meaning “tranquility.” The river now runs through the quiet countryside still farmed, beets and corn, and studded with 950 cemeteries. As you drive through villages rebuilt by the Germans using reparations money following the war, it’s hard to imagine anything happened here.

But over the rises and in the distance, monuments stand and everywhere signs recall the events of 1916.

It’s sobering, as it should be.

What do you know about World War I?

Have you ever heard of “The Somme?”

Tweetables

98 years later, you still can’t drink Somme River water Click to Tweet

What’s the Somme battlefield like today? Click to Tweet

How could 1.2 million people kill each other in two years? Click to Tweet

The post A Trip to the Western Front appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

October 15, 2013

The Nudist Colony Field Trip

Sequoia sempervirens in Redwood National Park (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

What sort of third grade teacher would take her students on a field trip to a nudist colony?

None that I know.

It was my idea.

In a box belonging to my now-college student daughter, I recently found thank you notes written by classmates after an infamous field trip we took into the wilds of Mendocino County.

It was the reference to keys that triggered my memory.

My daughter’s wonderful third-grade teacher, Mrs. Monroe, wanted her students exposed to the great outdoors. She established a classroom garden, assigined projects drawing pictures of seedlings and flowers and taught them to appreciate earth worms.

Mrs. Monroe even took the class on a field trip to her small farm where we ate “Pink Lady” apples fresh from trees and walked along a creek. She believed kids benefited from time spent in the natural world.

Her class awakened a love of math and science in my daughter–who majors in biology.

On this particular field trip we were headed in search of the world’s tallest tree, which had just been identified as standing among a series of other sequoias in Montgomery Woods State Park. We drove fifteen miles west of Ukiah to the end of the road. There we met park ranger Karl, whom I knew from boy scouts.

He led us on a hike through the lonely forest. He pointed out swordleaf ferns, widowmaker limbs, poison oak and other important items to know about in a forest. We forded a creek and hiked along a narrow trail. The hush of a redwood forest is dense and moist, soft somehow, and the children’s eyes grew wide.

We examined a banana slug–which made the girls shriek and the boys grin. Mostly we hiked in silence savoring the fresh air–it breathes in easier in the forest–and the green against mahogony colors.

Karl waved in the direction of trees so high it was hard to put your head back far enough to see the top. “One of those is the world’s tallest living thing, 369 feet high. You just can’t tell which one because they’re growing on a hillside.”

You can see a photo of it: here.

Karl was in a hurry that day, so after we tramped back to the parking lot, he jumped into his ranger truck and drove off. We collected our picnic lunches.

Except I’d been a mother long enough to know kids got bored easily, so I went back to the car and grabbed a couple books. I thought knock-knock jokes would entertain the children while they ate.

They liked the jokes.

But when it was time to go, we discovered I had locked my keys in the car.

15 miles from town. No cell phone service. Five miles from the closest establishment with a telephone.

There wasn’t enough room to take me and the three girls I’d driven in my car back to town, safely.

We decided to cram us all into one car and drive to the closest phone–we’d be able to see where the phone lines ended–and I’d call someone to retrieve us.

Five miles down the road, we came to a cluster of buildings. The phone lines ended at a walled compound that had a sign advertising bathing, rooms, and dining. The girls and I got out, the cars drove off, and I approached the gate.

It was an adults-only nudist colony.

The girls were eight.

I was old enough to know I couldn’t take them into an adults-only nudist colony, no matter how far from civilization we were,even in Mendocino County.

I escorted the girls to a nearby bench. “I need to go inside by myself to make a phone call. Why don’t you read these knock-knock jokes out loud and see if you can figure them out?”

“Why can’t we go with you?” my daughter asked.

“Children aren’t allowed. I’ll be right back.” I rang the bell and was admitted.

It was lunch time.

They dress for lunch.

The director frowned. “What do you mean you’ve been dumped off with three little girls in the forest?”

“I’d be happy to pay for the phone call. I just need to call one of the dads to pick us up.”

He pushed the phone toward me, crossed his arms and glared.

I dialed quickly.

“My keys got locked in the car and your daughter and mine are being held captive in a nudist colony. Could you pick us up?”

Once the dad stopped laughing, he said he’d come immediately. I thanked the owner and scurred out the eight-foot gate.

“Why couldn’t we go in there?” asked my daughter, the budding biologist.

“Adults walk around inside those walls without any clothes on.”

“Ewwwwwwww.”

Karl apologized for leaving so quickly when I told him the story–after he finished laughing. “But you did get to see the world’s tallest tree.”

He was right.

It was a day of biology in the raw.

What unexpected thing have you seen or learned on a field trip?

Tweetables

A nudist colony field trip. Click to Tweet

The world’s tallest tree and a nudist colony. Click to Tweet

Adventures on field trips: nudes or trees? Click to Tweet

The post The Nudist Colony Field Trip appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

October 11, 2013

Cultural Sensitivity in Fiction

How much cultural sensitivity do you need to have while writing a novel?

My friend Kathleen read “The Gold Rush Christmas” and wrote me a note of appreciation, but went on to make an interesting observation:

“I was leery of the totem pole, when I heard you had one in the story. However, I appreciated how it was used and the fact that it was something actually done added to that. You were so skillful on the dignity given to the natives, too.”

I appreciated her comment because I worked hard to make sure my story line was respectful and honest. Native Americans have had a difficult time assimilating to western culture and those of southeastern Alaska were no exception.

I first ran into the question of how to represent Native Americans in a culturally sensitive way in my first novella, “The Dogtrot Christmas.” My characters were living in 1836 Texas, how would they have referred to the locals who were often trying to steal, if not kill them?

Texas during the 19th century had a lot of problems with Native Americans. The Comanche Indians were basically hunted down by the Texas Raiders and killed indiscriminately for years. (See Empire of the Summer Moon for more details). “Native American” would not have been a term used by either the Tejanos or the Anglos of that time period.

Since my characters were speaking in dialect anyway, I just had them use “injuns” or “red man.” It seemed the least controversial while being historically accurate.

Political Correctness Needed?

Jane Kirkpatrick, one of my co-writers in A Log Cabin Christmas Collection, recently discussed the topic: On the Use of Political Correctness in Historical Fiction.

Jane had two important points to make. In regards to Native Americans, she observed that “squaw” was a derogatory term that would not have been used at the time and so she saw no reason to use it herself. She also noted the state of Oregon recently renamed many locations that used squaw–such as, say, Squaw Lake.

She then quoted writer Joyce Carole Oates as to why it’s important to respect others through the use of words:

A writer should do three things in a story: create empathy for a character and the flawed world in which they live, be a witness for people who otherwise might not have a voice, and memorialize. Given those things, I think that when writers use the more politically correct, present day terms, we are memorializing something with integrity and we’re giving voice to an otherwise silent witness.

Totem Poles

In my case, I didn’t give political correctness much thought when I wrote about a totem pole in my story. I wanted to be accurate and respectful, and so I went in search of a culturally accurate totem pole to represent Christmas. I found one carved by Rev. David Fison, based on his years of living with Native Americans in southeastern Alaska.

When I contacted Rev. Fison, he was pleased to have me use his totem pole but asked that I not invent anything–he wanted me to only use the information he provided. He’d spent years making sure his version made respectful sense to both the Natives Americans, but also to Jesus.

I didn’t have a lot of excess words to use in my novella, but since it was his totem pole and he had done the research, I honored his request. That’s what Kathleen was responding to in her note to me.

Rev. Fison, it turns out, also carved a totem pole for Easter. You can read an expanded discussion of his carving in an article here.

Totem poles were used by Native Americans as religious symbols, but also as a tool to remember their important stories. Rev. Fison provided an excellent representation of how a totem pole could be adapted to Christianity.

I liked the totem pole so much, I bought a small version for myself.

Writers walk a fine line between historical accuracy and political correctness. It’s important to be accurate, but also respectful. I’d never given the term “squaw” a second thought until I read Jane’s article. I’ll be more careful from here on in.

Of course, reading primary source documents can also help a writer understand how minorities were viewed in their time and society. I wouldn’t go so far as to include some of Mark Twain’s terminology used in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, I’d try to find a different way to refer to slaves. Perhaps the way diarists during the Civil War did it? The slaves were always referred to as “servants.”

I like that better.

What have you run into while trying to write about culturally sensitive topics? How have you reacted to upsetting terms when you’ve read them in books like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn? Do you think writers should feel free to write anyway they like no matter how someone might be offended?

Doesn’t offensiveness sell more?

Tweetables

How to write with culturally sensitivity. Click to Tweet

Insulting or historically accurate? Who cares? Click to Tweet

The post Cultural Sensitivity in Fiction appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

October 8, 2013

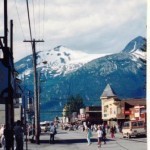

Traveler’s Tales: Sailing to Alaska!

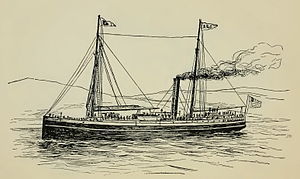

Alaska Steamer ‘Excelsior’ (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

I didn’t have any problem writing the section of “The Gold Rush Christmas” about sailing to Alaska. I put my heroes, Samantha, Peter and Miles, on a steamer and sent them off.

It was easy. I’d been sailing to Alaska myself, and like them, I slept on the top deck, ate miserable food, struggled with sea sickness, and rubbed elbows with my fellow Klondikers-seekers.

Like Samantha, I sailed to Alaska with a bunch of men. My husband, my father-in-law, my three sons and, just for the fun of it, our godson Devin. The boys were all under 11 years old and rambunctious.

The men were a little better.

In our case, we drove our van into the hold of an Alaskan State ferry and then hauled our camping gear up to the solarium on top of the ship. We were allowed to go down three times a day to retrieve items or pick up things we needed during prescribed 15 minutes when the doors were unlocked. We visited a couple times a day, mostly retrieving food and books.

Like the Harris twins and Miles, we staked out an area on that top deck. We laid our sleeping bags, a cooler, a bag of entertainment and  a duffle bag full of assorted clothing around the edges of our area. When we realized people were erecting pup tents, we claimed our two-man backpacking tent and set it up on the stern. The view each morning of our four day trip was fantastic.

a duffle bag full of assorted clothing around the edges of our area. When we realized people were erecting pup tents, we claimed our two-man backpacking tent and set it up on the stern. The view each morning of our four day trip was fantastic.

The children ran wild, gazed over the side, played video games (they got two quarters apiece each day). They heard lectures, played cards and even listened to stories. I fed them out of our cooler and once a day we ate in the dining room.

I spent long hours gazing at one spectacular view after another.

We sailed to Alaska with a cast of characters.

One morning my then-four-year old son whispered, “look, Mom. That man has a little fire in his hand.”

The little boy had never seen anyone smoke a cigarette! Watching a man puff smoke out of his nose and mouth amazed him!

The summer sky does not start to get dark in Alaska until close to midnight. (I could read in the tent without a light at 11 o’clock at ”night”). One evening, we pushed the tents aside, a fiddler joined us and we danced square dances. Many of our compatriots were seeking gold in Alaskan jobs–lots of college kids were headed to work in fish canning factories.

Like the travelers in “The Gold Rush Christmas,” we journeyed from Kitsap County, but we were on a vacation, hunting views and a different part of the world. Ours was only a three week trip (though we spent most of that driving . . . ) in between mosquito seasons.

We arrived in Skagway, Alaska at two o’clock on an August morning. When I’d asked the booking agent what we were supposed to do upon disembarking in the middle of the night, he laughed. “Start your vacation!”

The waterfront looked different 94 years after the events depicted in “The Gold Rush Christmas,” but the town still had a frontier feel to it.

We spent the night in a former brothel, but didn’t tell the boys who used to live there.

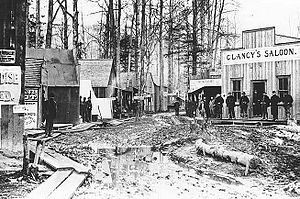

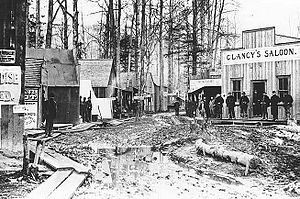

English: Muddy street scene, Skagway, Alaska, October 1897. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

So is White Pass, which we drove over in about half an hour. The views from the top were, of course, spectacular.

We ate a much better meal than that served by Samantha and Mollie in their tent restaurant, but it was easy to see traces of the fighting town Skagway once was. Soapy Smith’s saloon is a site to see, a statue of Mollie Walsh stands in a park and we saw the second half of the Klondike Gold Rush museum in this small town. The first half is in downtown Seattle (which we had seen the week before we left. I also had the boys watch White Fang).

There’s something special about visiting a location where you set a story, which is one of the reasons I wanted to write about Skagway and Alaska for A Pioneer Christmas Collection. The drama of the gold rush, the horror of the passes, the can-do spirit of the Klondikers, the excitement of sailing to Alaska, only to face the hardship of the terrain.

It made for a great story, a terrific vacation and a grand adventure for my men–to whom I dedicated my novella.

And it also made me laugh at how much of my trip was mirrored in Samantha, Peter and Miles’ sailing to Alaska, too!

Have you been to Alaska? How did you get there? What did you like the most?

The post Traveler’s Tales: Sailing to Alaska! appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

October 4, 2013

Floppy disks and Obsolete Technology

Do you have any floppy disks lying around your house?

Whether they’re actually floppy or not, are you depending on those floppy disks to save all your information forever?

Do those floppies house photos? Letters? Your tax records?

Do you keep them in a fire-proof safe? (Have you got one big enough?)

Worse. Are your old manuscripts safely tucked away on those floppies?

I thought mine were safe, and I was smug about saving, until we bought our most recent computer.

I could handle the fact it didn’t have a floppy disk drive since our old computer did and we could always use that computer to access information, right?

Wrong.

I wrote a 300 page, 938+ end noted family history called Pioneer Stock in 2000. I safely copied all the chapters individually onto their own floppy disk. (I’m calling it floppy, but you know it’s square, colorful and made of hard plastic). One day I wanted to send a copy of my work to a genealogy pal.

None of our computers could read the floppy.

The problem wasn’t simply that I’d written the manuscript in Word Perfect (Oh, how I loved Word Perfect!), but I wrote it on a computer that we bought in 1996. Somehow, the ability of my most up-to-date, every bell and whistle, computer, could not transcend that old operating system.

Unless I wanted to retype the entire manuscript (Good heavens! All those end notes!), I no longer had access to it.

This is no joke folks. I’m married to a nuclear engineer who has owned personal computers since 1983. He’s taken them apart, put them back together, and maintained them with his exemplary skills. He couldn’t believe it either.

It turns out that when Windows XP 2000 was released, old floppy disks could be used on the computers, but Windows XP used those floppy disk drives in a new format.

We didn’t worry about this because my same brilliant husband always made sure all our information was loaded on the new computer, every time.

Except once.

And unfortunately that gap in paying attention happened at the same time Windows changed the format on floppy disks.

Who would have thought the floppy disk we burned on our Windows 98 computer, would not be readable on any post-Windows XP operating system?

(If I sound like I know what I’m talking about, rest assured, I’m typing off notes from that aforementioned husband).

Six months ago, I became concerned about my inability to access Pioneer Stock, not to mention my grandmother’s biography The Rose of Mayfield and my grandfather’s biography written to celebrate his 100th birthday in 1990. My husband tried to open the manuscripts of our fast, impressive brand new computer. Not readable.

We bought a specific floppy disk reader that was “guaranteed,” to be able to read all floppy disks–except, when we got it we

[image error]

Imation USB 3.5″ floppy disk drive (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

discovered the fine print: none older that Windows XP operating system.

It seems we had stumbled into a growing problem. The obsolescence of data storage. A recent article in Smithsonian Magazine highlights and discusses the implications–particularly in regards to photograph storage–here.

My husband was particularly taken by the plea, “if you have an old operating system, please don’t throw it away. At the very least, advertise it on eBay for someone to buy.”

Apparently machines can no longer be made that can read those old floppy disks. When I frowned, my husband asked me how I would view a Beta tape. Did I know anyone who had a Beta machine?

(Actually, I do, but you get the point).

He called around to see if he could find someone with a machine. The one local guy told him, “People think I have some sort of super computer with a high powered piece of software that can read anything. None exists. All I have is barn filled with old machines. When people bring me a disk, I just try it in all my machines until I find one that can read it. If I don’t have one, I return it and say, ‘good luck.’”

My Facebook friends will remember we hunted for weeks for a Windows 98 machine. No one had one until we remembered an IT guy we knew at a Los Angeles high school. He asked around and one of his teachers had a Windows 98 operating system computer hidden in a closet. We made a donation to the school and got the machine we hoped could read our floppy disks.

We were excited, except we needed to download a driver to be able to read what we had. My husband prowled the Internet and finally found a website in Australia with the downloadable driver that enabled him to transfer data from the floppy disk to a memory stick (it was an old memory stick at that).

I cannot tell you how relieved we were when Pioneer Stock booted up onto our brand new, extraordinary computer.

We’ve saved it in a number of different formats, now.

Technology can be lost. It hardly seems possible but it resides in the knowledge of the people who manipulate it. When the last Saturn rocket was placed in a museum, the United States lost its ability to build Saturn rockets. Astronauts may have made it to the moon using computers with less calculating abilities than you have in your cell phone, but they got there.

We don’t know how to build a rocket to return to the moon now.

So, make sure you’re backing up your manuscripts and your photos onto something that will last. CDs are not projected to last more than 15 years. The cloud? Hopefully it will stay up there. Perhaps the real question is, which data storage method will be the next to die?

Floppy disks?

You’re already obsolete.

Tweetables

Back up your information anyway possible! Click to Tweet

Who would guess back up floppy drives are unreadable? Click to Tweet

How do you protect your data? Click to Tweet

The post Floppy disks and Obsolete Technology appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

October 1, 2013

The Drama of Primary Source Materials

Primary Source Materials are first hand accounts of events, like this:

Primary Source Materials are first hand accounts of events, like this:“I was too young to remember her. I do not have the faintest recollection of her. I was told my Aunt Hannah made a white dress for me with lace beading and ran a black ribbon through this beading for the burial services.

“The day of the services Aunt Hannah was holding me in her arms and when they closed my mother’s casket I waved my hand and said, “bye-bye, Mama.”

The day I copiedthose words, I stopped and put my head down on the keyboard. I wept for both Carrie who died following her second childbirth and also for my grandmother who lived 91 more years missing her beautiful, kind and loving mother.

Primary source materials is not a glamorous term and sounds staid and boring, but it can make scenes come alive and inspire curiosity:

“Spill it! We’re aching to know where and how you spent the night? Why the Winchester? And for whom the book on etiquette?” (Rev. R. M Dickey; Gold Fever)

Newspapers and diaries are excellent sources of information–primary, the first places things were reported.

Historians insist history cannot be understood without them–the eyewitness accounts of people on the ground.

Often, their poignancy speaks much louder than anything an author can imagine. As he prepared to fix his bayonet for the battle of Cold Harbor during the Civil War, one soldier scribbled the date on the last page of his diary followed by the fateful words:

“I died today.”

Adapting Primary Source Material

English: Muddy street scene, Skagway, Alaska, October 1897. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

I like to use primary source materials while writing historical fiction because it makes the story feel more real. I start with basic information about the location and history, and then scour the

Internet and libraries to find actual information written by people during the time frame.

For my novella The Gold Rush Christmas, my best source was Rev. R. W Dickey who spent the 1897 winter in Skagway, Alaska and wrote about building the Union Church. He mentioned townspeople, described what he encountered, and quoted unusual events in his book Gold Fever: A Narrative of The Great Klondike Gold Rush, 1897-1899.

He was the primary source of the amazing tale of the Skagway “sporting women,” “soiled doves” and “unfortunates,” as polite society called prostitutes.

When church member Mollie Walsh asked him to visit one of these women, the as-yet-to-be-ordained Rev. Dickey hesitated. But he went, reminded the dying woman about Jesus and “how he came to search for us and bring us home to our loving heavenly Father.”

“The funeral service two days later was held in the church, which scandalized some people. The girls of her own class were in attendance–practically all of them–their painted faces and showy ornaments marking them out from the few women of the other class. Some of the latter sat aloof and looked their disapproval.”

You can picture them, can’t you?

“It was a strange scene–probably fifty girls on their knees as we carried the coffin down the aisle.”

Rev. Dickey needed to visit the hospital and didn’t go to the cemetery, “but I paused long enough to watch the men reverently carrying the body of their erring sister toward her last early resting place, confident that Jesus to Whom she had looked had brought the wandering lamb home.”

I didn’t have enough extra words in my tightly-written 20,000 novella to include all of Rev. Dickey’s details or lovely turns of phrase. I had to condense the story line and so many of his actions were transferred to Miles, a not-ordained seminarian whose sense of propriety ran into a number of “how can you not?” questions in “The Gold Rush Christmas.”

Rev. Dickey ran into Captain O’Brien of the steam ship Hercules, who was curious about local news. He told the story of the sporting woman’s death and the sobbing unfortunates in his church, mentioning his own sermon. The captain listened with interest and then had a question:

“Do you think any of them do it, leave off, I mean . . . Get word to them that on my return trip . . . I’ll take all who want to go to Vancouver or Seattle. It won’t cost them a cent.”

When the reverend pointed out they’d have no money and would have to return to their trade, a packer standing nearby butted in:

“I’ll give the Captain a check for whatever he thinks he may need. Would a thousand do?”

The town conman, Soapy Smith, wasn’t likely to let his primary source of income go without a fight. The good men of Union Church, however, led by Rev. Dickey prevailed on the fearful sheriff to help the women. As the sun set that night, a group of church people escorted 40 prostitutes to the Hercules and waved them south.

An amazing story.

I’ve read a lot about the Alaskan Gold Rush. I’ve been to Skagway, Alaska and seen the Mollie Walsh statue in the park. I’ve read countless tales of missionaries, but had never heard of this one before.

I had to go to the primary source material to find out.

Where do you read for information when you want to know history? Do you like to read memoirs and personal histories, or do you prefer the history books?

Tweetables

How 40 prostitutes escaped 1897 Skayway Alaska. Click to Tweet

Using Primary Source materials for a better story Click to Tweet

Stranger that fiction: 1897 Skagway prostitutes escape Click to Tweet

The post The Drama of Primary Source Materials appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

September 27, 2013

Hail to the Unsung Heroes

Who are the unsung heroes in your life?

Who are the unsung heroes in your life?I’m not talking about the obvious unsung heroes like your mom or your saintly aunt. I mean the ones you may never have met who have done a service for you–whether they’ll ever meet you or not–out of enthusiasm for the topic or situation

I’ve been thinking about unsung heroes this week because I’ve connected with one. Chris lives in McMinnville, Tennessee and I met him through last week’s research serendipity.

He’s a fan of the real life heroine of my Civil War novel (the one that has been set aside four times so I could write a book for publication. It’s up next . . . but I’ve said that before!), and after learning about my visit, he took the trouble to send me information.

Gold mine information.

Information I’ve sought and wondered about for the eighteen months my confederate (Kim Bailey) and I have been researching together.

In addition to sending me the newspaper clippings I need, he also recently took over the position of Warren County Genealogical Association Bulletin Editor. If you’re a genealogist in that part of the country, he’s an unsung hero to you.

Indeed, in the years before Ancestry.com made everything you need to seek your genealogy as easy as filling in your credit card  number, people like Chris were the backbone and the heroes of all us old time genealogists. I met another one last time I was in Tennessee, Thomas Partlow, an archivist for Wilson County who personally transcribed countless volumes of county records. His transcriptions were bound into books and you can see them on the shelves behind him at the archives–or in the mother lode of them all, The LDS Genealogical Library in Salt Lake City.

number, people like Chris were the backbone and the heroes of all us old time genealogists. I met another one last time I was in Tennessee, Thomas Partlow, an archivist for Wilson County who personally transcribed countless volumes of county records. His transcriptions were bound into books and you can see them on the shelves behind him at the archives–or in the mother lode of them all, The LDS Genealogical Library in Salt Lake City.

I finished up the majority of my genealogical research in 2000 at that library. My husband took our two youngest children on tours around Salt Lake City for two days while I spent first 10 hours, and then 8 hours in the library combing the books for every last jot and tittle I could find about my ancestors. I methodically worked my way down the county shelves, one book at a time, examining every index for a long list of names.

When my husband finally dragged me out, nearly babbling, on the second day, I felt sure I had looked at everything possible.

Thanks to the hard work of people I’ll never meet and whose names I don’t even know.

I was wrong, of course, and over the years since I published Pioneer Stock, numerous folks have come out of the woodwork to ask further questions or provide additional information. I welcome them all.

They’re everywhere volunteering for no money to help others–amateur, of course, comes from the French word that means “lover of,” and refers to people who do something because they love it, not because they’re paid. They play musical instruments with me at church. They maintain countless genealogical forums on-line, they run the Boy Scouts and are behind all sorts of charity organizations.

They’re everywhere volunteering for no money to help others–amateur, of course, comes from the French word that means “lover of,” and refers to people who do something because they love it, not because they’re paid. They play musical instruments with me at church. They maintain countless genealogical forums on-line, they run the Boy Scouts and are behind all sorts of charity organizations.

I try to remember to thank them when I see them.

Or, in Mr. Parlow’s case, I saluted him and took his picture! And then I said “thank you.”

Here are some more unsung heroes whose lives affect us all, starting with the immortal Henrietta Lacks.

One other unsung hero in my own life–the “real” AJ who kept together a disparate group of World Magazine blog commentators by providing them their own website to keep their community going. Thanks, Aj!

Who are the unsung heroes in your life? Click to Tweet

How can you recognize them?

How can you be an unsung hero for someone else? Click to Tweet

The post Hail to the Unsung Heroes appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.

September 24, 2013

Are You a Book Hoarder?

I think I might be a book hoarder.

I’ve actually given away 250 books since our moving process began in June, but I’ve still got boxes to go through.

My husband won’t let me buy any more bookshelves and, really, I can’t blame him.

But is it book hoarding?

Here’s a definition from the Anxiety and Depression Organization of America:

Hoarding is the compulsive purchasing, acquiring, searching, and saving of items that have little or no value. The behavior usually has deleterious effects—emotional, physical, social, financial, and even legal—for a hoarder and family members.

This isn’t me. I can stop. I have stopped. No one in my family has complained except when it was time to pack or unpack them.

So I did that.

I grew up in a family that valued books–kept at the library. The first book I remember owning was a Golden Press cardboard book called Nature Stamps that came with stickers I placed in the book to illustrate the stories.

How do I know?

Come now. How could I throw away the first book I ever owned?

(Notice it has a brown paper bag cover? I’m going to let the adorable grandchildren read it to death–something not allowed their parents–and then throw it away. See? I’m making progress.

(And that Heidi? That’s one of the few books my mother owned–the pages are so brown and crumbling, I’m afraid to open it!)

This was our fourteenth move. For years I explained I couldn’t get rid of books because I didn’t know if I’d be able to find them again. I use the library a great deal and at each place we’ve lived, I’ve fallen in love with some book in the local collection. In the days before Amazon, I couldn’t be guaranteed I’d see those books at the next library, so I bought the ones I might want to read again.

Many are comfort novels I read when I can’t sleep. They soothe with their familiarity. Besides, I know how they end if I DO happen to fall asleep!

I held onto the Christian books because there was no telling what church I’d end up in and whether the church library would have what I needed as a reference. Sifting through them now, I see how outdated many are and how my mind either may have changed or simply learned the lessons that were so extraordinary once. Jesus in Genesis by Michael Esses, is an example. I know the Christology now, it’s time to pass that one on to a new believer.

Some I’m not so sure of. My copy of The Shack is annotated because I led a dissection of the book. Where should it go? The church library or the public library? Who would benefit more from reading my notes?

I’m trying to be ruthless. Books I haven’t read or thought about in years need to go. Books I have multiple copies of–the Bible, obviously–need to be passed along. Volumes I’ll need for research are perched beside me in the office. Atlases we regularly consult, all the travel guides, books written by friends, they remain on the shelves.

And of course all my children’s books are here waiting for the adorable grandchildren to find them in what we call “the giggle room.”

They’re worn, torn, scratched and the pages are smooth from use. I don’t know how many copies of Richard Scarry‘s Cars and Trucks and Things that Go I ultimately will purchase. But they’re here now and they’ll stay.

You’ve got to draw a line somewhere–book hoarder or not!

How do you decide what books stay and what books should be passed on? Click to Tweet

Do you think book hoarder is a term of honor or shame?  Click to Tweet

Click to Tweet

Are you a book hoarder? Click to Tweet

The post Are You a Book Hoarder? appeared first on Michelle Ule, Author.