Michelle Ule's Blog, page 111

November 4, 2011

Owning or owned by Rembrandt?

My husband and I once had an opportunity to buy a Rembrandt.

My husband and I once had an opportunity to buy a Rembrandt.

You know, as in the painter.

While visiting a small San Francisco art gallery in 1979, we poked around in the back where they kept their less important works. Two etchings by Rembrandt van Rijn of Holland were for sale, $1000 each.

We had $1000 in the bank. That's about all we had, but we had enough money.

My brain sparked with the concept. I could own a Rembrandt.

Oh, it wasn't a large etching and not particularly attractive, but it was a REMBRANDT.

With excitement singing in my blood I asked my husband if we could buy it. New at being a husband, he paused and then said, "if it's important to you, sure."

A Rembrandt!

Imagine the possibilities.

But all our savings?

"Let's take a walk and come back."

As we climbed the hills of the beautiful city beside a bay, I considered the practical implications. My husband was in the Navy. We'd already moved four times. Every time we moved in the future, I'd have to think about owning a Rembrandt. I couldn't trust the movers, which meant I'd have to carry the etching myself. It wasn't large, but did I want to be driving around the United States with a Rembrandt in my car? And would we need more home owner's insurance if we possessed a genuine art work?

I let my mind run even more wild. A Rembrandt. Owned by me.

But would I really own it, or would it own me by its requirements on my time, mental energy, insurance and actual pocketbook?

I could have owned a genuine Rembrandt.

But I never did.

That was an important moment in my spiritual maturation–having an opportunity to possess a fantastic dream but choosing not to take it.

The Bible talks a lot about possessions and our attitude toward them. We're warned against covetousness and not using possessions for selfish reasons. I personally have come to see possessions as tools for God to use. Had I purchased that Rembrandt, it might have put me in touch with artists. I might have used it to spark conversations with people in my house. But in the long run, I saw that it would demand more of me than I wanted to give.

Haven't I been happier for 32 years owning reproductions of Rembrandt paintings, rather than an actual stamp-sized etching I'd have to worry about?

Absolutely.

Though isn't it fun to dream?

Have you ever set aside something you thought you wanted when you weighed what it would cost beyond just the money? How did it go?

November 1, 2011

Circulating Valuables

[image error]Eighteen years ago, my husband decided to read all the works of Sir Walter Scott. We lived in Hawai'i at the time, and I methodically requested Scott novels every time I went to the library. Because the Hawaiian library system covers all the islands, some of the books had to be shipped to O'ahu over water.

One volume came to us from the big island and we handled it gingerly when it arrived. It looked old with colorful plates and gilded pages and had only been checked out a couple times according to the white label glued inside the front cover. The copyright date was 1895. It can't have been a first edition, but it was an early one. We marveled the library allowed it to circulate, surely the book was valuable?

I returned it to Aiea Public Library's front desk with awe. "Look at this book!"

The clerk shrugged as he reached for it. "So?"

"You're not a librarian, are you? I need to talk to a librarian."

He beckoned to an older woman in the back room. I showed her the copyright date.

She reverently reached for the book and ran her palm down the leather binding. "Oh, my goodness! You checked this out?"

She understood its value. I doubt the book saw the light of day again . . .

It reminded me of a time at UCLA when my roommate retrieved a book by Eleanor Roosevelt from the University Research Library (now the Charles Young[image error] Library). She opened the pages with reverence, and then gasped. "Eleanor Roosevelt autographed this book! Why did they let me take it out of the library?"

I sat beside her on the bed and touched the black signature. "Amazing."

"I just plucked it off the shelf." Her eyes gleamed with promise. "I could steal this book. What was the library thinking in letting it circulate?"

"What would you do with it?"

"I don't know."

I'm happy to report she returned the volume when she was done with her paper and went on to become a district attorney. I have no idea, however, if the book is still on the shelf.

A quick browse through the Internet just now revealed the books range in value. An 1895 version of Lady of the Lake in good condition currently goes for $39.95 on Abe's Books, an Internet-based book store specializing in first and early editions.

On the other hand, a signed limited edition of Eleanor Roosevelt's It's Up to the Women is advertised at $7500.

[image error]I purchased my most expensive book, The Oxford English Dictionary, through the Book of the Month club. It retailed at $75 back in 1975, but I joined the club and got it for about $20. It comes with it's own magnifying glass in a drawer on top of the case because the print is so small.

I see Amazon.com is selling a used version for $114. Hmm, I could make a profit after 36 years . . .

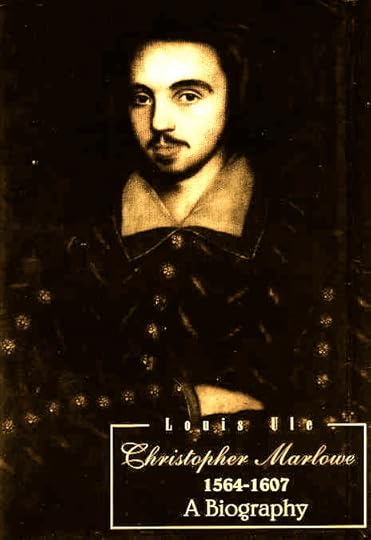

Probably the most valuable book I own, however, doesn't circulate because it truly was a limited edition. Written by my father-in-law, Louis Ule, after 25 years of research (or, most of my husband's childhood), it's a biography of Christopher Marlowe–demonstrating in thick lugubrious sentences how Marlowe wrote the works attributed to William Shakespeare.

I've thought to rewrite it over the years, to make it more palatable to modern readers because the story is compelling and rich. Louis did some amazing research. He even wrote computer programs analyzing Shakespeare and Marlowe's writing to demonstrate frequency of word usage. (Those programs were written for main frame computers using punch cards; how much simpler it all would be today.)

We can't reproduce the book; the vanity publishing company reneged on their deal and we never got the 1500 copies promised. It's cherished because of what it represents: Louis' lifetime passion, my husband's childhood, and a magnificent story. He even autographed it for me.

Valuable , and cherished, indeed.

What's your most valuable book and why?

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 28, 2011

Traveler's Tales: Savoring Coas Bookstore

I could barely get my suitcase zipped up for all the books given to me at the American Fiction Writers' Conference in September. I wasn't too worried, even though I had two stops to make before returning home to the west coast. The best gift was Ann Voskamp's One Thousand Gifts, which I read on the plane. My personal favorite, of course, was my own A Log Cabin Christmas Collection, which I signed and gave to a dear friend in El Paso.

I could barely get my suitcase zipped up for all the books given to me at the American Fiction Writers' Conference in September. I wasn't too worried, even though I had two stops to make before returning home to the west coast. The best gift was Ann Voskamp's One Thousand Gifts, which I read on the plane. My personal favorite, of course, was my own A Log Cabin Christmas Collection, which I signed and gave to a dear friend in El Paso.

With those two out of my luggage and the zipper sighing in relief, I figured I was home free. My stargazing son in Las Cruces wasn't going to give me a book.

No. But he did take me to visit a bookstore. "You'll really want to see this one, Mom."[image error]

"I don't have any room in my luggage, Stargazer."

"Trust me, this is well worth a visit."

Coas Books, Inc. was a short walk from his downtown cottage on a beautiful warm late summer eve. We only had forty-five minutes in the store, but I was in rhapsody walking through the doors. It's a used bookstore, you see, and they've got a lot of great old books.

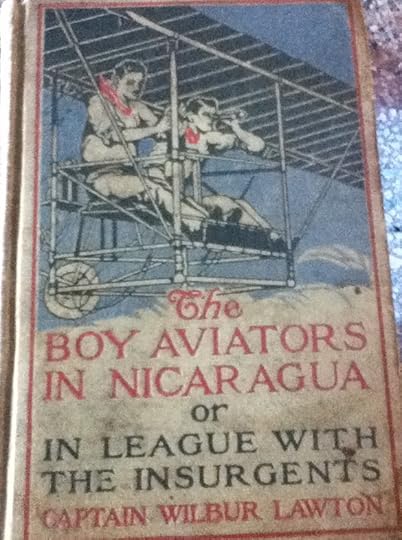

I'm talking ancient books; not simply the types of books I read in my childhood. These are volumes my grandmother might have read. Look at the date on this book: 1910. My grandmother was five years old, though probably not reading The Boy Aviators in Nicaragua in Mayfield, Utah.

I'm talking ancient books; not simply the types of books I read in my childhood. These are volumes my grandmother might have read. Look at the date on this book: 1910. My grandmother was five years old, though probably not reading The Boy Aviators in Nicaragua in Mayfield, Utah.

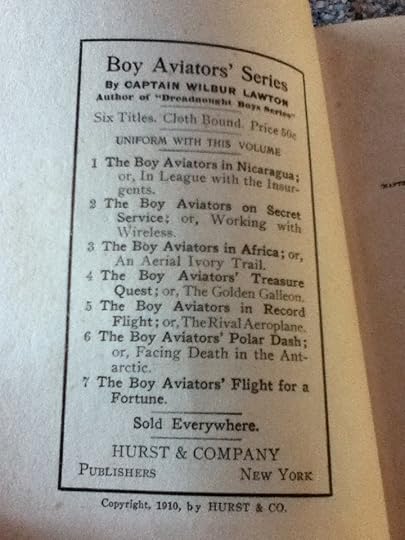

Who would have guessed there was an entire series, "sold everywhere," about boy aviators in Africa, the Secret Service and facing death in Antarctica? Clothbound and 50 cents, the pages are still highly readable if brown and spotted with age.

I'm not sure what I smell when I stick my nose between the pages–because of course I bought it–antique paper? Pulp wood? Adventure?

Adventure?

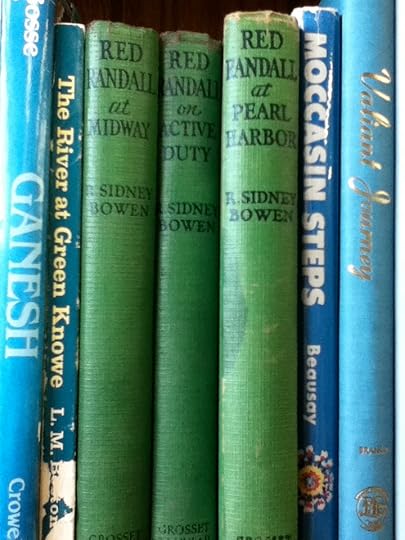

Who knew so many "pulp book" series were written and published during the 20th century? The store featured an entire line of boy-readable tales from World War II. Red Randall at Pearl Harbor, anyone? How about Red Randall at Midway? Or as a midshipman? Or in Burma?

I opened the books to the front page and showed my son the statement about paper rationing during the war. Yet while some of these books looked fragile, they certainly could hold their own for a good read. Clothbound over pasteboard, I guess, makes for a sturdy 100-year-old covering. I could scarcely keep my delight in check as I danced in front of an entire wall of old kid books, none younger than 1950. What a find!

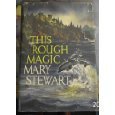

Indeed, the entire bookstore was a spin through my reading history. I recognized hundreds of volumes on the shelves as I wandered up and down the aisles. Here's an edition of Mary Stewart's This Rough Magic I first read in 1973, there was one of the million mass-produced copies of Airport, auxiliary text books I used in high school; there were long-forgotten friends on every shelf.

Indeed, the entire bookstore was a spin through my reading history. I recognized hundreds of volumes on the shelves as I wandered up and down the aisles. Here's an edition of Mary Stewart's This Rough Magic I first read in 1973, there was one of the million mass-produced copies of Airport, auxiliary text books I used in high school; there were long-forgotten friends on every shelf.

There's nothing new under the sun, as Solomon reminds us, and of the making of books there is no end. That sprawling, cranny-filled store in the center of town holds a treasure trove of satisfaction as it proves the wise king's words.

I didn't want to leave, so it's probably just as well Stargazer brought me to the store in the final hour of the work day. I could have lost myself in the past, in story, in the joy of smelling the books, in touching their well-loved bindings and in remembering all the hours I'd spent in their company. Such a gift to be able to read. Such a pleasure to be told a great story. Such fun to share with my son.

Thanks, Coas Books!

But that brings me to a question. Until now, the oldest book I owned was a 1917 Pollyanna Grows Up. What's the oldest book you personally own? How did you get it?[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 25, 2011

The Frustration of Hearing a Great Story.

[image error]I attended a military wedding many years ago in which I misbehaved.

Oh, I looked proper enough with my terrific hat and pumps, but inside I seethed.

I really should apologize yet again to my Navy wife pal, Anne, who was sitting beside me because I whispered to her throughout the service.

I couldn't help it. The situation was so over the top ridiculous, I couldn't keep quiet. It really was a gossipy mess of a marriage.

But that's not what irritated me. I was frustrated because I'd never be able to write a story in which such behavior took place because everyone would assume I was writing about the couple.

It was just another fine story gone to waste.

I can't speak for every writer, but I've always got a story running through my brain. I'm considering angles, thinking of subplots and wondering how I could translate some event into a bigger story–maybe even one with a moral or a reflection on the goodness of God.

God may have been good that day at the wedding–hey, they got married!–but I wondered how I could shade the tale to tell a story that wouldn't reflect badly on the couple or on me.

I give up. I'll confess my own sin and forget all the details of theirs.

But it's a problem I run into all the time. I trained as a journalist, I love to hear stories–and the more irony-filled the better. I love to share the outlandish behavior of people I meet; the absurd situations I constantly find myself in, and the pointed stories that make us all pause and say, "huh."

I know how to keep a secret; I've been trained in confidentiality. But if it's not clear I'm in a confidential situation, the reporter instincts kick in and I'm taking mental notes and framing the story.

Which is why I get frustrated when a really great story comes my way and I know I can't share it with someone else. Or, I know I can't recast it into a novel.

A great story can be used to illustrate a point. It can amplify an emotion. It can teach a lesson. We're hard-wired to pay attention to stories. Jesus, after all, used parables to great effect in His ministry.

Several of my friends have terrifically romantic stories–but they're off limits for my writing.

Though maybe the one about the submarine and the shipyard worker . . . she never reads my writing anyway . . .

If you're a writer, how do you manage? And if you're a listener, how do you know if a story is true or not? :-)

October 20, 2011

Travelers Tales: Ghosts on the Streets

I returned to my home town earlier this week, stopping by to get a feel for the place where I spent my first 18 years. I'm working on a novel that takes place there 20 years ago, and I wanted to revisit some of the sites in my story, to see if I've forgotten anything.

I returned to my home town earlier this week, stopping by to get a feel for the place where I spent my first 18 years. I'm working on a novel that takes place there 20 years ago, and I wanted to revisit some of the sites in my story, to see if I've forgotten anything.

I had.

My heroine lives in my late mother's late best friend's house–a place I housesat during my college years so I know the layout. But I had forgotten the cute little family-run store around the corner. I thought the apartments were farther away. I had no idea there was a deep ravine two blocks to the east. And was Paseo del Mar always such a steep drop off at the end of the road?

Fortunately on the day I visited, fog sat on the neighborhood and I remembered how sound carries so differently through the soft gray marine layer. The surprise of joggers disappearing into the misty blanket and dog walkers appearing from the same, added twists to the plot curing in my brain. A good trip.

But one in which I was shanghaied continually by memories fanning in and out like cards in a bridge hand. One minute I was six-years-old, my nose pressed against the car window as we jounced down steep Ninth Street. A turn of the corner and I felt bicycle pedals pumped by my fifteen-year-old legs. When I passed the high school, I paused at the corner–wasn't there always a red VW bug parked in front of that house?

Maybe in 1973.

Here's the spot where Fred had his fatal heart attack; where we left the car to hike down to Cabrillo Beach to avoid parking fees. My children played at the Point Fermin Park playground and I was 29 again; my parents living in the condo at the top of the hill.

Except they're all gone now–tucked into cement crypts at Green Hills.

And through it all I was my current age, but not of one mind. I examined the clutter of Gaffey Street as a woman who has traveled the world and wondered why this street was so messy. I knew the short cut to Weymouth Corners without thought but wondered what had happened to the buildings that once loomed so large. And how could Polly Ann Bakery still be in business, but not Peterson's Market across the street?

I didn't travel with just my memories. I quizzed a reporter friend, describing a red witch hat house on the bend in the road where I used to babysit. The owners had talked of rum running to the house on the cliff during Prohibition and late at night watching the fog roll in and the muffled sound of crashing waves, I had waited with nerves alive.

Donna didn't know the house, though she smiled politely. When I drove past, I saw it had been replaced by a mega-mansion, history and funkiness squashed by granite. Like several of my memories.

My fourth-grade friend's mother invited me to tea in a sun drenched kitchen–I hadn't seen her since the 1984 Olympics. We laughed about the years and the people we knew; told each other stories and I felt so loved.

But I had forgotten the reason I craved visiting her, beyond the fun of seeing someone I always liked. The same size, age and heritage as my mother, she asked the same loving questions and delighted in my answers. I felt like I had visited with my mom again–and I left with tears in my eyes. I haven't seen my mother in sixteen years, since the day she dropped dead while playing golf.

Where to go for lunch? Who's the pastor of our church? How could anyone have chintzed up our old home in such a silly fashion? Look how terrific Averill Park has been kept up.

Where to go for lunch? Who's the pastor of our church? How could anyone have chintzed up our old home in such a silly fashion? Look how terrific Averill Park has been kept up.

It was a relief to end at another well-loved housesitting spot where the trees and plants still overgrew the yard and laughter ruled the air. Dogs barked up a storm and houseplants threatened the windows. Photos stuck out of crannies, fresh vegetables on the counter.

And my mother's other dear friend as alive and full of blarney as ever. Her sister, too.

Ghost were on the street, yes, but so were happy memories. My home town is more varied and special than I remembered.

And I can't wait to go home again.

How about you?

October 18, 2011

Traveler's Tales: I-5

[image error]I'm on the road today, driving the length of California on another silly excursion that involves two different sets of family members. I drove down I-5 and am returning on US-101. If you see me, wave.

It's really a classic California cultural experience, driving I-5. Heading north from Los Angeles, once you leave the suburban valley, you wind up alongside the California acqueduct into a mountainous area where the stars gleam bright at night. Coming down, along the "Grapevine"–so named because it twists and turns like a grapevine–you hit the flat San Joaquin Valley, the breadbasket of the United States.

The Grapevine has been there forever, it's the main pass to southern California, and very steep. Cars are probably overheating on that stretch of the road today. My grandfather's car broke down at the base of the Grapevine in 1941 and the family camped for three days waiting for repair parts. My dad used to augment that story with, "we were practically Okies."

I've had many memorable trips down the center of the state through Interstate 5–which in the early years was one long desolate four-lane road that zoomed through farmland, past cows and skirted the acqueduct nearly to Sacramento. I first drove it 39 years ago with my father giving directions: "Don't fall asleep."

In those early years rest stops hadn't been built yet and towns were few, if any, on the actual road. One friend told of a drive with her husband and children during this time when bathroom were hard to come by. The miles clicked by and nothing appeared even on the horizon. She finally instructed her husband to just pull over.

As he stopped the car, she rummaged over the back seat and found a MacDonald's bag. She tossed out the left over fries, hamburger wrappers and everything else before exiting the car with the bag in hand. Leaving one of the doors open as a sort of shield, she squatted down next to the pavement and put the bag OVER HER HEAD.

"What are you doing?" her husband asked.

"I don't want anyone to recognize me!"

I laugh every time I drive that stretch of the road.

We know the rest areas between San Francisco and Los Angeles like the back of our hands. On a good day it's a four hour stretch from where 880 bends in from San Francisco, and Santa Monica where family members live. On a bad day–like Thanksgiving Eve-the same drive has taken us eight hours of bumper-to-bumper madness.

Returning north late one Saturday after Thanksgiving, we left the last spot to turn off and headed into the black night, a long line of red lights ahead of us. Ten minutes up the road we came to a halt and sat. For an hour. Fortunately, we were listening to George MacDonald's classic The Phoenix and the Carpet, on tape and it kept us entertained. When we finally reached the problem, we saw beautiful horses running beside the freeway; their 12-horse trailer on its side.

That was a bad night. The delay, however, worked out fine for us–the book on tape concluded when we pulled into our garage at home.

You're never quite sure what to expect. My sister-in-law roared up the road one Christmas Eve, making it in less that five hours from Los Angeles. She talked about the wild excitement of going 90 mph and being passed by a CHP car. Everyone wanted to get home that night and tickets were not being written!

But it also can be dangerous. The Tule fog often settles without warning and visibility goes to zero, way too fast. We know to check the road conditions before we start south at night. Or rather, we seldom drive I-5 at night in the late fall and early winter. Too many people have died on I-5 and CA 99, because of the fog.

start south at night. Or rather, we seldom drive I-5 at night in the late fall and early winter. Too many people have died on I-5 and CA 99, because of the fog.

It's curious to drive the road even in the daytime during the winter. Coming down the Grapevine, you can see the fog layer sitting on the road and we always grow very quiet until we're through.

The best way to travel I-5 is with chatty friends–Lucia and I began a conversation as we drove out of my brother's driveway in Santa Monica and didn't stop talking until nine hours later when we arrived at her house north of Ukiah. Who knows where the time went–two Sicilians telling tales with the miles speeding by? We almost forgot we had children in the back!

It's worth one trip, driving the length of I-5. Stop for breakfast at Harris Ranch, or lunch at In-N-Out burger. Watch for the stars at night–or the fog in the winter. Puzzle over Crow's Landing–what is it? And in the spring, savor the blooming almond trees.

And if you see anyone squatting along the side of the road with a bag over her head, well, it won't be me but let's ignore her anyway.

October 14, 2011

On Living with a Novelist: Plotting–or at least Dealing with the Laundry

(Actually, I prefer to call it scheming. That sounds a little less diabolical.)

(Actually, I prefer to call it scheming. That sounds a little less diabolical.)

What exactly is plotting?

About.com defines plot this way: "Plot concerns the organization of the main events of a work of fiction. Plot . . . is concerned with how events are related, . . . and how they enact change in the major characters."

What does that mean, specifically, in living with a Christian novelist?

As a Christian I'm interested in how the events of my life work together, you know, as in Romans 8:28: "Everything works together for good for those who love the Lord and are called according to his purpose."

That means as events tumble in and out of my everyday life, I believe there is a bigger purpose behind them than just doing the laundry, cooking dinner, and maybe writing here and there. The pieces fit together in a way I may not recognize, but which I believe are moving to an interesting climax that will change my character. You know, like in a character arc?

Wikipedia helps us with that definition: "A character arc is the status of the character as it unfolds throughout the story . . . Characters begin the story with a certain viewpoint and, through events in the story, that viewpoint changes."

Because I see my whole life within the context of God changing and molding my character from rough hewn baby to perfect old lady, I expect to see character improvement. The longer I spend reading and studying the Bible, the more I expect to act at least a little like Jesus.

Which is why my life is all about plot, even when I'm only doing something as mundane as the laundry.

With four children, I've spent a lot of time planning how to get the laundry done. I bucked the chore for years and actually wondered when my turn would be done–would I have to do laundry for the rest of my life?

I'm not sure what I expected–my mother to move in and whisk it all away?

But one day as the Maytag's maw beckoned, I came face to face with my attitude about serving my family.

The plot thickened, or at least the pile of dirty clothes got bigger, as I wrestled with my character. Eventually I came to see that laundry, like the tide, is a continual non-negotiable, daily event. I became disciplined about doing it. The clothes got cleaner, my heart improved and this subplot of my life moved to resolution.

Moments of humor along the way lightened the load–for example, the ecstatic day we purchased our first washing machine confirmed I had reached adulthood. Embracing laundry provided a coming of age plot point.

We even had a deathbed scene recently when the Neptune's motherboard failed for the fourth time.

My character arc in regards to laundry is winding down–the high point came when the children began to do their own laundry. I almost miss the constant hunt for stray socks and the trauma of clean uniforms not being ready. I don't even have to worry about plotting when to do the wash–we've got plenty of hot water now.

Ridiculous?

Maybe. But a novelist is always trying to iron out the details to make their plot convincing and interesting.

[image error]

October 10, 2011

On Living with a Novelist: the Fear Factor

We've been married a long time and my husband and I have found equilibrium in our foibles, but he still gets impatient when I voice fear–particularly about things that aren't likely to happen.

We've been married a long time and my husband and I have found equilibrium in our foibles, but he still gets impatient when I voice fear–particularly about things that aren't likely to happen.

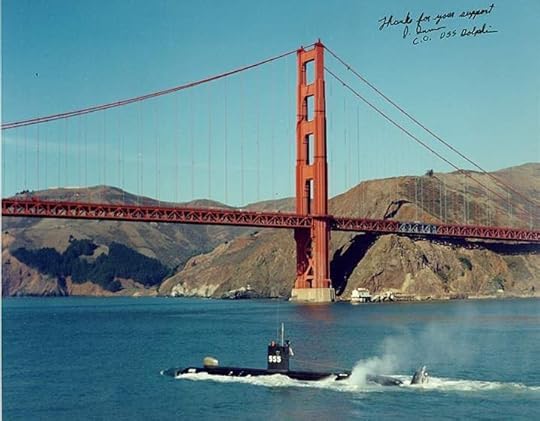

Some of that is our character–he's a former steely-eyed killer of the deep, a professional military officer, a risk-taking businessman who trusts in the Lord.

I try to trust that God knows what He is doing with my life and where He is taking me.

I haven't suffered many dramatic horrors, but you never know . . .

Of course I was a cub scout leader for seven years and with three Eagle Scouts in the family, spent 17 years being prepared. I understand how frustrating it would be to live with someone always fretting about "what-if" scenarios and trying to calculate how to escape situations that may never occur.

What's my problem?

The answer came to me one day as we drove in San Francisco. The problem isn't me, per se, but my profession. I'm a novelist. I'm supposed to dream up "what if" studies, ask questions and try to twist a story to ratchet up the emotional component. I've got a program constantly running in my brain, wondering how to complicate my story line. Whatever story line it is.

My husband didn't buy the argument. "That's ridiculous."

Really?

What does he think about when he drives across the Golden Gate Bridge?

What an engineering marvel it is? What it felt like to ride a submarine underneath? How much paint they need to keep the color up? Wouldn't it be nice to be sailing on the bay today?

Or perhaps he remembers the story he heard once of the commanding officer swept off a submarine and never seen again?

No. He never thinks of that sea story unless I bring it up.

Meanwhile, my brain flits through all sort of scenarios once I'm past the marvel of, "people come from all over the world to view this bridge and I just see as a short cut to the airport."

What if there's an earthquake? What if one of these oncoming cars suddenly swerves into our fast lane? What would happen if one of the wire coils snapped? What would it feel like to fall through the air to the water below? Would the car float? How did that little girl slip under the railing and fall to her death? Has anyone ever been blown off the bridge? Do bikes ever run into each other on those blind spots around the base?

What would happen if the Fastrak responder didn't work when we went through the toll booth? Would a police car come after us?

Sometimes the fog is down to the deck plates when we cross. What if we just drove off the end of the bridge without knowing it? What does it look like from above? Can you see the road or just hear it through the damp? How did our friend propose in the middle of the bridge? How would you get the ring back if it slipped out of your hand into traffic just as you proposed? And what if it was foggy?

You see?

Have any of those things ever happened–other than the poor Navy commander lost at sea? (My husband's comment is always, "imagine the paperwork," while I'm picturing instead the terror of the frigid water and unbeatable undertow).

Well, what do you think about when you cross the Golden Gate Bridge?

He still thinks I'm worrying needlessly, but I'm much less fearful now that I understand where the questions come from. I "worry" with a more detached point of view. If it's just an exercise in novel writing, I don't have to be afraid.

Besides, I remind myself the same God who numbers the hairs on my head knows when my days are going to end, whether in the fog over the Golden Gate or in my bed at home 30 years from now.

It's not a "what if," it's a "when it's time."

And there's nothing to be afraid of, resting in God's hands, at all.

On this, my husband and I agree.

October 7, 2011

Four Generations of Spitting

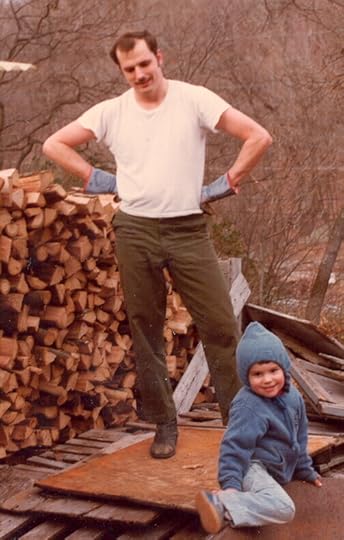

I've been with my adorable grandchildren this week and yesterday watched my four-year-old grandson build a "house" out of cardboard, chairs, a wheelbarrow, plastic child's car, two pieces of plastic and a lot of imagination.

He described what he was doing the whole time, explaining the need to keep raccoons out of his basement, "because they only come out at night, Grammy."

It felt very familiar, nodding and trying to match his earnest descriptions with respect.

He moved his hands in elaborate patterns as the good 1/8 Sicilian he is and I suddenly felt transported back to another yard, another place, another intense little boy explaining how something worked.

Indeed, not just the adorable grandson's father, but his grandfather–who spun stories of engineering marvels the first time I met him at 16–and even to his great-grandfather who always thought deeply and creatively about any problem that came his way.

Was the adorable grandson just another chip off the old block? All four Ule men would like that description because it sounds mechanical–using a tool to do something constructive.

something constructive.

Or was he really a "spitting image?"

The grandfather in this line up likes to talk about "spitting image" as a contraction from "spirit and image." In this way, a person so described demonstrated both a similar spiritual state, or character, to the person he's being described as looking like.

I like this concept because my grandson reminds me so much of his own father–an enthusiastic little boy who wanted to be right, do well, and explain everything in a manner understandable to even someone as innocent of engineering schemes as, well, me.

(After knowing four generations, I can testify, it's a family trait).

Over on the Phrase Finder website, they have a different idea for the term, wondering if it might really be 'splitting image', i.e. deriving from the two matching parts of a split plank of wood. . . . The theory has its adherents and dates back to at least 1939, when Dorothy Hartley included it in her book Made in England: "Evenness and symmetry are got by pairing the two split halves of the same tree, or branch. (Hence the country saying: he's the 'splitting image' – an exact likeness.)"

I don't really think so.

For most people, the words "spitting image," probably derive from the notion two people couldn't be more alike than if one had spit the other out of his mouth–thus people who look very much alike, if not act the same.

These four Ule men in my life are different in many ways, but that engineering mind– got to figure out and work the problem, which may be the result of being first born males in all their families– appears in all of them.

These four Ule men in my life are different in many ways, but that engineering mind– got to figure out and work the problem, which may be the result of being first born males in all their families– appears in all of them.

Their eyes twinkle, too, and they all can take a joke.

But give them an engineering problem, and they're on it.

It made me think of Genesis where God conferred with the other two in the Trinity and said, "Let us make man in our image." In God's image, He created us–to be like him.

The more time I spend with the Lord, the more I try to behave like Him. The more time I spend with God, the more I should reflect His spirit and image, too.

It's a family trait.

Or at least I hope so.

Just as I have had the joy of knowing four generations of Ule engineering men, so, too, I've had the exquisite joy of seeing God's light and character reflected in my husband, son and grandson.

And they don't even have to spit.

October 5, 2011

Which is the Good Point of View?

I was at a writer's conference last week and so I've been thinking about point of view.

I was at a writer's conference last week and so I've been thinking about point of view.

Among writers, point of view is one of the primary things to consider when writing a novel—determining whose eyes and thoughts to use in telling the story.

But point of view is important in real life as well, particularly when looking at two important passages in Scripture. A verse I think about often is Job 2:10 "Shall we accept good from God and not trouble?" (NIV)

That's a pretty-in-your-face verse, but if we take it apart and look at it from a different point of view, it seems friendlier.

Let's start with that word good, particularly in the infamous context of Romans 8:28, "we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose."

Works for the good of those who love him–who is determining what is good in this verse? God himself.

You know, the creator of the universe, the God before all time, who loves you with an everlasting love and underneath are the everlasting arms. That God. He decides what is good for YOU.

Now, I might think winning a million dollars in the lottery would be a good thing for me. But would it, really?

Would that be God's idea of good for ME? Or is that MY idea of what is good?

But what if winning a million dollars meant my family began squabbling over the money? What if my family was destroyed because of all that money?

What then would be good? Winning the money or not winning the money?

I'd go with not winning, how about you?

(For the record, if someone gave me a million dollars I would pay off the student loans of all the young people I know and contribute the rest toward the mortgage at our church.)

Of course, we should move on to trouble, but again, by whose standard? Mine or God's. And if God uses trouble in my life to move me back to him, could you almost argue that trouble, too, can be good?

These verses bring us back to one central truth: do I trust God with my life or do I think I know better?

If God, who is outside of time and looks down from heaven at the whole of my life in one glance, determines something is good for me, even if it doesn't feel good to me, who really has the better point of view to decide on what is good for me?

It pains me to admit it some times, but I'll vote with God.

I call this "turning the prism," to look at things from a slightly different angle. Sometimes if I just alter the way I look at something–try to see it from God's point of view, or even from that of a family member–the definition of good can change.

And usually, sad to say, for the better.

Thanks be to God.