Michelle Ule's Blog, page 114

August 8, 2011

Nicaragua: What does Prayerful Grace Look Like?

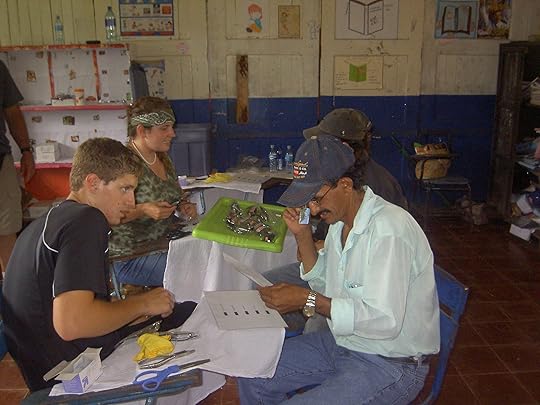

Baking heat, no moving air. We had to put up dark curtains over the "windows" in this cinder block school with a metal roof so Jon can read the auto-refractor. School children out of class hang on to what windows are uncovered, chattering at what they see.

Baking heat, no moving air. We had to put up dark curtains over the "windows" in this cinder block school with a metal roof so Jon can read the auto-refractor. School children out of class hang on to what windows are uncovered, chattering at what they see.

A line outside drifts beyond our sight. A dozen people sit in beat up desks, the women with their ankles neatly crossed. The linea de espera–waiting line–to see John Jones and get the vision diagnosis is six people deep. Two people chat with the registrars in rapid Spanish. Four people stand near the door and are handed papers with a small cut-out box; we have to figure out which is their dominant eye. And Hooper shines a flashlight onto a sign to test distance for a young woman giggling behind her fingers.

I can feel the sweat slipping down my back and wicking out of my blue aerobics shirt. An ageless man, his face a mahogany brown with furrowed lines from working in the sun, stands beside me unblinking. He pushes his ballcap off his forehead and stares straight ahead. Jon has just indicated the top of the machine, "Mira aqui," look here. He pushes a button and we listen to a beep as the laser scans the man's eyes.

While I wait for the long beep which signifies we have a good reading, I look at the man wearing clean, worn clothing and high rubber boots and I can feel my eyes soften the way they do when I look at my adorable grandchildren. I don't even know what this man's name is, though I can glance at the card and see: Juan Carlos. All I can think of is how dignified he looks in front of this technologically advanced machine, and what an honor it is to be here to serve him.

Lunch was long ago, over three hundred people already have been seen today. We're weary on the fourth day of serving, but this is what prayerful grace looks and feels like.

Many people prayed for months about this trip; folks back home in Santa Rosa continue to pray for us. The Holy Spirit moves where he wills, and bestows blessings and grace upon grace.

My daughter Carolyn spent three weeks this summer working at Mt. Gilead Christian camp and shared a talk she heard with us the tired evening of day two. One day at devotions, the Mt. Gilead camp director Steve Todd reminded the counselors: "You may have done something hundreds of times, interacted with hundreds of kids this summer. But for each kid, this is their first time encountering this experience at camp. Remember this: it's their first time."

I thought of that as the people inched forward, some anxious about standing before this beeping machine as Jon bobbed and weaved trying to get the best reading. Would it hurt? What was happening?

When I had a moment, I tried to explain in my limited Spanish. "The machine reads the shape of your eye and tells us if you need glasses and what kind. It doesn't hurt."

Sometimes the machine got crochety, or the batteries died. Sometimes Jon couldn't get a good reading. "Abra sus ojas mas," we would say, imitating what it looks to like to open your eyes wide.

They smiled and relaxed when he told them, "Okay."

I scribbled down the number and sent them to the next line. Occasionally I'd laugh: "Su ojas son joven," telling hard working men in their fifties that their eyes were still young. They always grinned back.

Prayerful grace. My feet ached, my legs were tired, my eyes started to hurt and it was just so sagging hot and muggy.

And yet.

Their first time.

I could actually feel God's grace extended: "My children. Ones I love. Be my hands and feet. Serve them."

It was an honor and a privilege.

August 7, 2011

Nicaragua: Living in a Treehouse

We stayed at a lovely spot called Sabalos Lodge on the Rio San Juan. With a half dozen thatch roofed huts strung along the river, it felt just like living in a tree house. Simple, humble and rustic, but utterly fun as well.

We stayed at a lovely spot called Sabalos Lodge on the Rio San Juan. With a half dozen thatch roofed huts strung along the river, it felt just like living in a tree house. Simple, humble and rustic, but utterly fun as well.

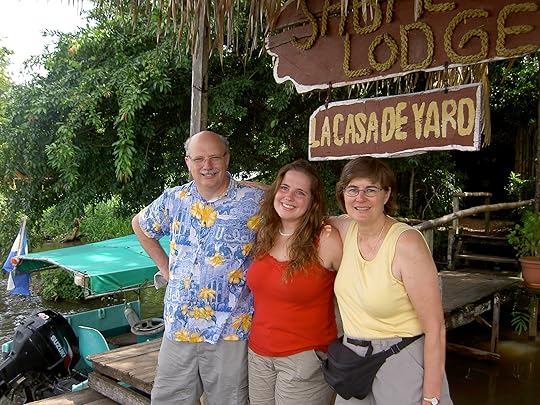

I had no idea what I was in for when the boat glided up to the dock. A carved sign announced the lodge with a note underneath that we were at Yaro's casa–and the rangy man with white hair met us with a firm handshake. I felt like I had entered a story when I walked up two steps to a bamboo reception area open to the outside world on nearly all sides. Imagine my excitement when a wooden bridge over a lagoon where the boys were chasing caimen alligators, led me to a path through the brush alongside huts on stilts lining the waterway.

And the birds calling in the trees? No wonder the huts were named for characters out of Tarzan!

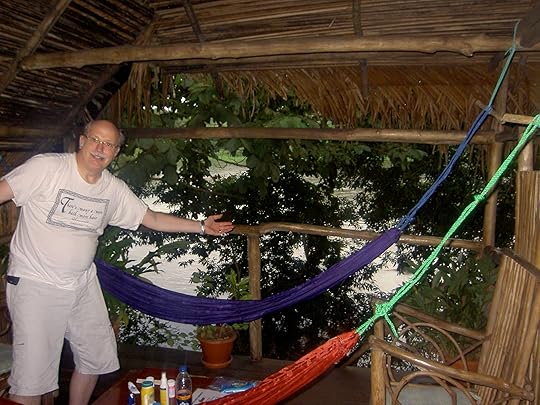

We stayed in Chita, a two-room "bungalow" made of bamboo and open to the river flowing nearby. The common area held several simple chairs, a table and two hanging hammocks.

The bedroom boasted a double bed and a single futon, both swathed in mosquito netting. The walls on two sides reached to our shoulders and gaped so we had an easy view at the pathway to the north and the open sky and river to the south. No windows, no screens, and a towering A-framed roof overhead. The sound of rushing water never ended and the birds chittered and squawked in the trees–when they weren't upstaged by the hoot of howler monkeys.

This tree house even came with a bathroom, replete with cold shower and a flush toilet. Who could complain about that? One afternoon a yellow frog with dark green eyes poked his head through the thatch and watched me shiver. Even now I'm not sure if it was the water or the reptilian eye that caused me to hurry out. It was fun to look past the shower head and watch a monkey swing past.

This tree house even came with a bathroom, replete with cold shower and a flush toilet. Who could complain about that? One afternoon a yellow frog with dark green eyes poked his head through the thatch and watched me shiver. Even now I'm not sure if it was the water or the reptilian eye that caused me to hurry out. It was fun to look past the shower head and watch a monkey swing past.

Our furniture was simple but comfortable. We had a table for our night stand, a platform for our luggage, a bare light bulb overhead. It was sufficient and easy to live with. We didn't have to lock our door–which was good since it only had a latch. We didn't worry about the neighbors because the thick foliage gave us privacy.

The tall roof overhead kept out the monsoon rains that poured down in the evenings. Down near the boat dock, a shelter housed six hammocks where we could gather at dusk and watch the birds fly to roost on an island in the middle of the river. One of the few electrical outlets where you can charge your I-pod or camera battery was in the shelter. Or in the dining area, equally open to the elements.

There's something to be said for the casual, simple living of a tree house. With lizards skittering in and out, the prospects of bugs an ever-present excitement and monkeys sitting in the trees nearby, you feel like you're in the jungle.

But the beds are soft, the water cool and the sounds of nature close at hand. The food is good, too, and all of it off the property.

I wouldn't want to live in a treehouse all the time, but for five days on the Rio San Juan, it worked very well for us.

I wouldn't want to live in a treehouse all the time, but for five days on the Rio San Juan, it worked very well for us.

August 5, 2011

Nicaragua: Giving Birth along the River

Picture yourself as the typical teenage girl in the Rio San Juan area of Nicaragua. You finish school, probably around fourteen, and live in a small village– perhaps one like Las Colinas (the hills) or the prosaically named Kilometer 20. You meet a nice guy, probably don't get married, and find yourself pregnant like the majority of your friends. You're a long way from an obstetrician, or any physician for that matter. The closest clinic may be in the small town of Sabalos, or the spot more frequently visited by tourists, El Castillo. Five doctors are on call in this area in the southeastern corner of the country, just north of Costa Rica.

Picture yourself as the typical teenage girl in the Rio San Juan area of Nicaragua. You finish school, probably around fourteen, and live in a small village– perhaps one like Las Colinas (the hills) or the prosaically named Kilometer 20. You meet a nice guy, probably don't get married, and find yourself pregnant like the majority of your friends. You're a long way from an obstetrician, or any physician for that matter. The closest clinic may be in the small town of Sabalos, or the spot more frequently visited by tourists, El Castillo. Five doctors are on call in this area in the southeastern corner of the country, just north of Costa Rica.

According to statistics from UNICEF , infant mortality rates in Nicaragua are high: 23 in 1000 pregnancies. The maternal mortality rate is equally disconcerting: 170 per 100,000 deliveries. The closest ultrasound machine is up river at Boca San Carlos, the county seat on the shores of Lake Nicaragua. It's a two-hour emergency drive from Sabalos over a bumpy road; a rapido boat can get you there in about an hour, but do you really want to risk delivering in a narrow ship?

machine is up river at Boca San Carlos, the county seat on the shores of Lake Nicaragua. It's a two-hour emergency drive from Sabalos over a bumpy road; a rapido boat can get you there in about an hour, but do you really want to risk delivering in a narrow ship?

In El Castillo, where Flavio Rodriguez, a general physician, runs a small medical clinic, the delivery table and the ER room are the same spot. He doesn't perform caesarians; too dangerous. And nearly everyone gives birth without any meds.

If you're like most women, you'll gain about 10 kilograms (about 22 pounds) during your pregnancy. And if you're enlightened enough or the above statistics unnerve your family, you leave home about 36 weeks into your pregnancy to enter a small maternity home in Sabalos, so you'll be close to Flavio and his colleagues when the time comes to deliver.

If you're like most women, you'll gain about 10 kilograms (about 22 pounds) during your pregnancy. And if you're enlightened enough or the above statistics unnerve your family, you leave home about 36 weeks into your pregnancy to enter a small maternity home in Sabalos, so you'll be close to Flavio and his colleagues when the time comes to deliver.

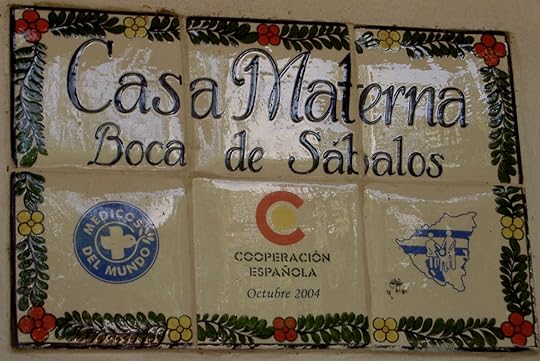

Casa de Materna was established in 2004. The clinic where normal deliveries take place is just up the road. When I visited last week, some eight women were in residence, they can house up to 17. Two women rocked in cane-backed chairs and passed the time on a warm tropical morning. Several times a week a Peace Corps volunteer visits, and they always have the director to talk with. They were pleased to meet me and showed me around their humble quarters, just off the main street of Sabalos.

The two communal sleeping rooms share a common bathroom which has two of four toilets currently functioning, along with several cold showers.

The two communal sleeping rooms share a common bathroom which has two of four toilets currently functioning, along with several cold showers.

The women share their household duties, simple because they have so little.

Cooking in that hot climate is done outside, with the rest of the kitchen a simple counter with sink and stove.  A refrigerator is available for the food women bring with them–mostly fruits and vegetables–or that provided by the home. Everyone in this part of the world eats a lot of plantains and pinco de gallo: rice and beans–which together make a complete protein. They don't bring much with them, so laundry is not onerous. Everything is hand washed and hung on the line to dry.

A refrigerator is available for the food women bring with them–mostly fruits and vegetables–or that provided by the home. Everyone in this part of the world eats a lot of plantains and pinco de gallo: rice and beans–which together make a complete protein. They don't bring much with them, so laundry is not onerous. Everything is hand washed and hung on the line to dry.

26% of women in Nicaragua deliver without any medical attention. The time they spend in Casa Materna is an opportunity to receive health information they can use: while we were there, we brought all the women sunglasses and our Peace Corps translator explained their need. She also teaches about HIV prevention, they do a 15-minute simple HIV test developed by a local nurse, and discuss how to deal with domestic violence–that it doesn't have to happen.

After a normal delivery, a woman stays in the Sabalos clinic for 24 hours. She's then released, usually to walk home with her newborn.

10-20% of local deliveries end up as Caesarean sections and cannot be performed in Sabalos or El Castillo. Flavio used to have a portable ultasound machine that provided information about potential dangerous deliveries–which meant women could be transported to the closest hospital in San Carlos well in advance (another Casa de Materna is in San Carlos and Matagalpa). The machine finally died and he asked if I knew or could help them find a used machine for this area–a population of over 20,000 people.

Plans are in the works and money is being sought to add a small surgical facility to the clinic in Sabalos. Caesarians could be performed there, along with cataract operations and appendix removals. The San Juan Rio Relief committee has been working in conjunction with the Nicaraguan Department of Health and Rotary International is interested in helping as well.

If you would like to help, or know someone who could–particularly in obtaining a used ultrasound machine– contact me or the San Juan Rio Relief committee: sanjuanriorelief@cox.net

It's about having healthy babies, right?

August 4, 2011

Nicaragua: El Nuevo Testamento

Christian missionary work has always been based on sharing the good news that Jesus Christ died in order that men and women might be free from the guilt of their sins and able to live with God forever. The original Christians who witnessed Christ's life, death and resurrection eventually sallied forth from Jerusalem to tell the world what they had seen: the God they had known in the flesh who rose from the dead.

Christian missionary work has always been based on sharing the good news that Jesus Christ died in order that men and women might be free from the guilt of their sins and able to live with God forever. The original Christians who witnessed Christ's life, death and resurrection eventually sallied forth from Jerusalem to tell the world what they had seen: the God they had known in the flesh who rose from the dead.

While the Old Testament contains the writings of prophets who describe the Creator of the Universe in all his awe-inspiring glory, the New Testament relates Jesus' life and how his death and resurrection changed our ability to know the God of the Old Testament. It's a powerful book of God reaching through time, space and eternity to show his love for us, while we were yet sinners.

The Bible is the best selling book of all time, of course, and the impetus for so much of western civilization from paintings to music to books themselves. The Bible was the first book Gutenberg printed using moveable type in 1450. The original schools in north America taught reading for the express purpose of enabling people to read the Bible. Even today, Wycliffe Bible translators learn obscure languages so as to translate the Bible into every language on earth.

We flew to Nicaragua with 230 pounds of Bibles in our luggage. We carried two bags each with our clothing stuffed around the thin paperback books. We also brought toys to distribute to the local children and some Bible story booklets for them. We could only carry 500 Bibles and they needed to be parceled out carefully, 125 per day. They were always gone by lunchtime; only a handful of people didn't want one.

With trembling hands, staring through new lenses, people opened the book to examine the Word of God. They almost always smiled when handed a book and many carried them away with reverence.

The optometrist told me, "many of the older people take great comfort and are so happy to have a Bible. This is a good gift."

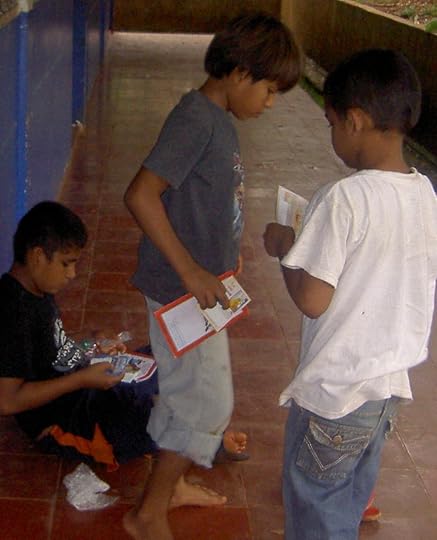

Television has recently come to Rio San Juan, or at least a more clear picture through political means I'll discuss later. The tropical climate can make owning a book challenging. I'll talk about that later, too. We didn't see many books in the classrooms; perhaps owning a book is unusual. But they took this book, and we were happy to hand them out. It was so much fun to walk through El Castillo and see a little girl reading her booklet after visiting us.

Even the boys paused in playing with their bouncy balls to look through the booklet. As we walked back to the boat in Sabalos, we saw children all over the streets with Bible booklets, some reading, some just sifting through to look at the pictures.

Even the boys paused in playing with their bouncy balls to look through the booklet. As we walked back to the boat in Sabalos, we saw children all over the streets with Bible booklets, some reading, some just sifting through to look at the pictures.

"I'll never forget how an older woman's entire face lit up when I handed her a Bible," one of my colleagues said.

"The children were excited with the booklets," another added. "My prayer is that God's word would be effective and they would learn how to pray and apply it to their lives."

Running an eyeglasses clinic for over 1100 people served several purposes. By being Jesus' hands and feet, we provided them with the tools they need for their day-to-day lives. But we also provided an even more important opportunity.

In Luke 4:18, Jesus explained why God sent him to earth: "He has anointed Me to preach the gospel to the poor; He has sent Me to heal the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind and to set at liberty those who are oppressed."

Anyone who has eyes to see and read, can find that freedom in the pages of El Nuevo Testamento.

August 3, 2011

Nicaragua: Me? A Memsahib?

Knowing me, some friends were surprised to hear I was headed to the jungles of Nicaragua. Who could blame them? While it's true I'm a seven-year veteran of the Cub Scouts, the mother of three Eagle Scouts and I once spent 9.5 straight weeks camping (hey, it was Europe), I'm not known for my fondness for hot weather, insects or cold showers.

Knowing me, some friends were surprised to hear I was headed to the jungles of Nicaragua. Who could blame them? While it's true I'm a seven-year veteran of the Cub Scouts, the mother of three Eagle Scouts and I once spent 9.5 straight weeks camping (hey, it was Europe), I'm not known for my fondness for hot weather, insects or cold showers.

If that wasn't bad enough, I AM known for my inability to work machines and tools, and my arthritic thumbs often cause problems. I'm not a nurse, engineer, strong young man, cute young woman, physical therapist or experienced eye care volunteer. I've already detailed my foibles with foreign languages here. What good was I?

And, worse, what if I fell apart completely and turned into a total memsahib?

Sahib means "friend" in Arabic and commonly has been used as a courteous term in India for "Mister," usually directed at Europeans. Under the British Raj, the word used for female Europeans was adapted to memsahib, a corruption of the English word "ma'am" when added to the word sahib. Rightly or wrongly, to my mind it speaks of an indolent woman lounging in a cool dress sipping tea and clapping her hands as she orders her servants around.

I can't bear to be thought of as a useless decoration. But I seemed to lack some of the necessary abilities for this trip. Why sign up?

My daughter asked me. I had to go.

So I, in turn, invited my husband–an engineer.

I took great solace from the Scriptures that remind us that the body of Christ needs its many members, skills, talents, abilities and, well, failures. Or, perhaps it's more correct to remember God has called us to be faithful, not successful.

My husband the skilled engineer and I, along with Stephanie who trained on the auto-refractor, were the only novice missionaries on this trip. The first thing my husband did upon arrival at the clinic, was pull out his steel wool and cork grease (contributed by my clarinet) and set to work preparing the pliers and eyeglass fitting tools for this year's work. By the time the first person arrived at the fitting desks needing glasses, the tools were working perfectly and he began to twist and turn the frames to fit the person needing them. He also fixed the battery-operated fans.

(Our team included another engineer and, better yet, the son of an engineer. They were able to make repairs on glasses in addition to fitting them properly).

I observed for awhile and felt very uncertain about my technical abilities–those awkward thumbs and that history of breakage. Six people happily settled into the happy room–the place where people put on spectacles, often for the first time, and could actually see. The look of wonder, the slowly spreading smile of joy, the mouth dropping marvel of lines on a hand or birds on a tree. It's a great job to share in that happiness.

"Just put yourself into the missionary mindset," encouraged Rachel Kent, my colleague who has made this trip twice.

Missionary mindset? I usually write a check . . .

I hung around feeling useless until I saw the Peace Corps translators were running back and forth as they tried to determine dominant eye. I could help there. I stood about 20 feet away and waved at the nervous patient holding up a piece of a paper with a hole cut out.

I put a big smile on my face and called out the answers as they peered through the box at me. "Izquierda!" (Left) for someone who looked at me with their left eye. "Derecha," for a right-eye dominant individual. I waved again, they laughed and the young women doing all the translating didn't have to run up and down the room.

On day two, I wrote down the auto-refractor readings and joshed with the folks awaiting their turn. My Spanglish was sufficient to order them around, saying things like "abra sus ojos mas," (open your eyes more) and direct them over to John "vaya ala esta linea espera," to hear the results.

On day three, my daughter and her teenage cohorts thought I should try my fumbling hands at fitting. I worked on six pair of glasses, confidently twisting the pliers and making the frames square. Chatting about technical details in Spanish, however, defeated me and I ran off to the eye dominant chart shortly thereafter. It was hard to manipulate the tools and clean the lenses when my thumbs didn't want to work.

Besides, two people returned with their glasses and my husband had to fit them properly. Two-third success isn't that bad is it?

Handling the distance tests, eye dominance chart and running the lines. Waving at the kids, chatting with the old ladies and smiling, smiling, smiling and laughing. Did it help?

I hope so. My team told me it did. The real translators could talk. 1079 people moved through effortlessly.

And I didn't have to clap my hands once.

"Estoy una senora, nada mas."

August 2, 2011

Nicaragua: Eyes in need, cataracts indeed

The Rio San Juan area of Nicaragua is such a poor area that health care opportunities are far flung or often unavailable. One of the reasons our church, along with the Rotary club of Santa Rosa and other partners with San Juan Rio Relief, have returned for five years to run eye glass clinics is there is no optometric help in the area. In the past, folks from our church, St. Mark Lutheran, have hiked or ridden four-wheel drive vehicles into the jungle and farmlands of southeastern Nicaragua. The young people, in particular, have returned with stories of broken bridges, ankle-deep red mud and sketchy vehicles. We got it easy on our trip–we stepped into a boat and sailed to either El Castillo or Sabalos, short river journeys from where we stayed.

The Rio San Juan area of Nicaragua is such a poor area that health care opportunities are far flung or often unavailable. One of the reasons our church, along with the Rotary club of Santa Rosa and other partners with San Juan Rio Relief, have returned for five years to run eye glass clinics is there is no optometric help in the area. In the past, folks from our church, St. Mark Lutheran, have hiked or ridden four-wheel drive vehicles into the jungle and farmlands of southeastern Nicaragua. The young people, in particular, have returned with stories of broken bridges, ankle-deep red mud and sketchy vehicles. We got it easy on our trip–we stepped into a boat and sailed to either El Castillo or Sabalos, short river journeys from where we stayed.

In El Castillo, we set up our clinic in the community center, a large room often used as a church that included moveable pews. The larger room with double front doors and jalouise windows running along the north and south sides, was where we registered our patients, tested for their dominant eye, used charts to get a distance assessment and eventually fitted those in need with glasses.

In a smaller, dark room in the back, we used a portable auto-refractor to measure their vision. We marked the numbers down on a card and the patients visited John Jones, the trip leader.

An experienced Rotarian who has participated in eyeglass clinics around the world, John would shine a light into their eyes to assess for two things: cataracts and the formation of pterigiums. Using Rafael or a Peace Corps worker as translator, John then explained what he had seen to the often nervous patient. He'd mark the card and send them into the main room where someone would fit the patient with glasses.

Sometimes the numbers from the auto-refractor, or John's observation, indicated a far greater problem than the need for spectacles. Fortunately, we had an optometrist with us from Managua, Dolores Jarquin.

Dolores studied for eleven years in Cuba and is an attorney as well as an optometrist in a Managuan clinic. She spoke gently, clearly and with tenderness to the patients who came to her. She also set aside several Bibles each day and when she had a patient, usually an elderly one, who needed some comfort she would give them a Nueva Testamento. At least once in the last five years, eye surgery has been done in this area. Dolores was screening for potential candidates, particularly for cataract surgery.

Dolores studied for eleven years in Cuba and is an attorney as well as an optometrist in a Managuan clinic. She spoke gently, clearly and with tenderness to the patients who came to her. She also set aside several Bibles each day and when she had a patient, usually an elderly one, who needed some comfort she would give them a Nueva Testamento. At least once in the last five years, eye surgery has been done in this area. Dolores was screening for potential candidates, particularly for cataract surgery.

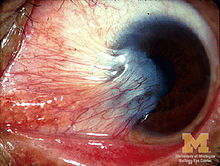

I didn't realize cataracts are usually caused by over-exposure to the sun–which is why they primarily are found in the elderly. Older people, particularly ones who work outside, have had their eyes exposed to the sun more than younger folks sitting in classrooms or offices. The closer they live to the equator, the more exposure people have to the sun. In poorer parts of the world, the chances they've worn sunglasses to block some of the glare–or have even known to do so–are minimal. Cataracts and their distant cousins pterigiums, were the most common chronic physical eye problems we saw in Nicaragua.

Pterigiums (also spelled pterygiums) are like cataracts in that their growth over the cornea blocks the ability of the eye to work properly. They take a while to develop and their growth can be slowed if precautions are taken one they're detected. We handed out a lot of sunglasses, particularly to young people whose vision was otherwise fine, as preventative measures. They can develop in either eye, individually or at the same time, and can be painful. Many of the people we met, including me, were surprised to learn how important it is to shade your eyes properly. (In North America, surfers are more likely to develop pterigiums than the average person).

they're detected. We handed out a lot of sunglasses, particularly to young people whose vision was otherwise fine, as preventative measures. They can develop in either eye, individually or at the same time, and can be painful. Many of the people we met, including me, were surprised to learn how important it is to shade your eyes properly. (In North America, surfers are more likely to develop pterigiums than the average person).

Our San Juan Rio Relief liason/translator Rafael explained in an animated way that the farmers need to wear large floppy hats like his–not ball caps whose brim shaded their face but did not block sunlight coming from the side–which plays a role in the development of pterigiums (click on the link and read about it in Wikipedia). The rest of us put on our sun glasses and tugged our hats into place when we stepped foot outside.

Our San Juan Rio Relief liason/translator Rafael explained in an animated way that the farmers need to wear large floppy hats like his–not ball caps whose brim shaded their face but did not block sunlight coming from the side–which plays a role in the development of pterigiums (click on the link and read about it in Wikipedia). The rest of us put on our sun glasses and tugged our hats into place when we stepped foot outside.

Meanwhile, plans are afoot to add a small surgical clinic to the humble medical clinic in Sabalos, thus enabling more routine surgeries like cataract operations or emergency appendectomies to be done on-site, rather than having to take a bumpy two-hour ride up the road to San Carlos. It all takes money, of course.

For more information on what I was doing in Nicaragua, read my initial post on the subject here.

August 1, 2011

Nicaragua: We came, we shared, we opened their eyes

Twelve members of our church, St. Mark Lutheran, have just returned from a trip to Nicarauga. We handed out 500 Bibles, nearly 2000 pair of glasses and saw 1079 folks. A total blessing and a terrific trip for all of us.

Twelve members of our church, St. Mark Lutheran, have just returned from a trip to Nicarauga. We handed out 500 Bibles, nearly 2000 pair of glasses and saw 1079 folks. A total blessing and a terrific trip for all of us.

We flew to Managua on TACA airlines and thence to San Carlos at the mouth (the boca) of the Rio San Juan in a twelve-seater plane. An hour-long boat ride took us to Sabalos Lodge, a cluster of huts looking like the Swiss Family Robinson Treehouse at Disneyland. We stayed there five nights.

The centerpiece for the trip was four days of eyeglass clinics–two days in El Castillo and two days in Sabalos proper. The humid weather was 35 degrees warmer than it is today in northern California, and monsoon-heavy rains fell daily. I wore an OFF insect repellant machine and took malaria pills. Fried plantains appeared at every meal. We slept under mosquito netting and took cold water showers in a hut without windows or screens.

I had a fabulous time.

The best part was the people we served. Dignified, stoic, neatly-groomed and patient, they held up a card at arm's length so I could determine their dominant eye. Some had a distance screening exam. If they were over 35 years-old, their eyes were "read" by an autorefractor.  John determined their need for glasses and we found and fitted a pair that matched the need in their dominant eye.

John determined their need for glasses and we found and fitted a pair that matched the need in their dominant eye.

Some people got both reading and distance glasses; everyone under 35 got sunglasses as did most of the folks who only needed reading glasses to see. To see the total joy on their faces, was a gift everyone –including you–should have.

It was an honor to serve; combining satisfaction and grace and bestowing good news to so many people in the poorest corner of the poorest country in central, and possibly all, America.

My husband, daughter and I were one of three family groups on this trip. Two teenage boys and their parents joined us, along with a couple and a woman without her family. Our San Juan Rio Relief Nicaraguan liason, Rafael, and a Managuan optometrist, Delores, traveled to San Carlos with us. Five Peace Corps members joined us as translators and livened up our group with good cheer and local knowledge.

We could not have accomplished half of what we did without those seven "locals," nor would we have wanted to try.

This was the fifth time our church sent a group to the Rio San Juan area. We worked out of a community hall in El Castillo and took over several classrooms in an elementary school in Sabalos. In addition to the free glasses, we handed out 125 Bibles a day, along with Snoopy dogs (reflecting the hometown we shared with the creator, Charles Schultz), Bible story books and bouncy balls for the children.

I'll be writing for the next several weeks about the experience. Join me and share our joy!

July 29, 2011

Mosquitoes and Spiders and Snakes, Oh My!

I can't believe it, but I don't think I've ever been on a missionary trip before.

I can't believe it, but I don't think I've ever been on a missionary trip before.

My husband reminds me we helped at an orphanage in Juarez, Mexico once but I'm not sure that counts since we stayed at my friend's house with a shower and just had to cross the border every day.

This time we're headed up the San Juan River in Nicaragua, a different animal all together from Juarez.

We fly to Managua, shift to a small 12-seater plane and fly over Lake Nicaragua. We land in San Carlos at the mouth of the river and catch a two-hour boat ride. We're headed to Sabalos Lodge.

Once in Sabalos, we'll conduct eyeglass clinics for the local populace on four different days. Members of our church, St. Mark Lutheran in Santa Rosa, have run these clinics for the last five years. Our daughter went on this trip last year and helped hand out 1200 pair of glasses and 500 Spanish Bibles. We're hoping to at least duplicate that number on this trip.

It's an important task. People travel for days to come to the clinic. For many, it's their only opportunity to get a pair of glasses.

A Managuan optometrist travels with us for difficult cases, but for the most part our volunteers use a portable auto-refractor to get a close diagnosis and then hand out glasses. Before my daughter went last year, I had no idea cataracts were caused by exposure to the sun. A large percentage of people living near the equator, pretty much anyone over 50, have some form cataracts. By the end of her first trip, my daughter could pick out cataracts from across the room.

That's why everyone who visits us, whether they need reading glasses or not, will get a pair of sunglasses. We've got pink ones for the teenage girls and sturdy plastic frames for everyone else.

In addition to meeting their physical needs, we'll also be handing out Spanish language New Testaments. It's amazing how quickly the Bibles are picked up–one to a family. My daughter said some people wanted the Bibles more than the glasses and when they got both! Excitement!

This trip is a stretch for me. I don't like small planes, detest bugs, am afraid of snakes, worry about diseases and having to communicate in Spanish has been for me, literally, a nightmare on many occasions. But I take great consolation in the Scriptures that remind me that God's strength is made perfect in my weakness. He'll have plenty of opportunities on this trip!

Any of you been on a mission trip? What did you learn and do you have any advice? I'm going to need it!

July 25, 2011

Life with a Blind Dog: Watch out!

I didn't realize for a long time that my dog was blind and I had become a seeing-eye human. Sure, she fell off the walkway a couple times and stumbled over the curb, but for the most part Suzie trotted beside me as easily as she always had. The fact we were on a broad path around Spring Lake, probably is why I was fooled for so long.

I didn't realize for a long time that my dog was blind and I had become a seeing-eye human. Sure, she fell off the walkway a couple times and stumbled over the curb, but for the most part Suzie trotted beside me as easily as she always had. The fact we were on a broad path around Spring Lake, probably is why I was fooled for so long.

As soon as we learned the truth, however, walking her became a little more problematic. We followed the same paths around Spring Lake, which she managed fine as long as bikes didn't come too close. I usually walked with friends and she could keep track of her surroundings by the proximity of my voice. On her right, four and a half feet higher. We're connected by a leash and years of practice walking together.

Unfortunately, she walked so smoothly, I often forgot I was a seeing-eye human and more than once walked her into a rock formation guarding a bridge. She startled, fell back and I felt awful.

Gordon Setters are smart dogs and she knows lots of words. But if you were a blind dog and your owner shouted, "Stop!" would you continue to hurl yourself down a path? If your owner told you, "wait," would you doggedly follow after her, even if it meant you ran into bushes, bird baths and stumps of wood?

The only command that seems to work these days is, "Sit." But stay? Not a chance.

You also have to make noise, for while she cannot see she can hear. This became obvious the day our toddling granddaughter paused and the dog walked right into her. She hadn't made enough noise for Suzie to realize she was there.

walked right into her. She hadn't made enough noise for Suzie to realize she was there.

Of course Suzie still follows the toddler around–she smells interesting after a meal.

Yesterday, she led the way around Spring Lake with me on the end of an extended leash. She trotted like the prow of a ship, not pausing as we covered the three miles around the lake. A small terrier cowered as we went past. "Is she friendly?" the owner asked.

"Blind," I said. "And I don't trust her with a dog she cannot see."

On the other hand, when her old walking partner Murphy, an Australian Shepherd, arrived on Monday, she ran up to him and spun around chasing her tail in glee. Did she care that she nearly ran into the two-foot high flower bed?

Books about blind dogs tell you to differentiate different parts of the house so the dog can figure out where she is. We've got throw rugs in front of the doors and her food dish sits on a plastic place mat on the hearth. She's only lived in the house nine years, but still seems to have trouble.

I've taken to clapping my hands or snapping my fingers to keep her following me. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't; too often it seems she has a mind of her own . . . and "watch out!" doesn't seem to slow her down.

You have to trust a seeing-eye dog or seeing-eye human and that makes me wonder how often God, who sees my life in all it's timeliness past and future, tries to get my attention with finger snaps or tugs of a leash. How often do I launch out on my own, blithely unprepared for the rocks God is trying to help me swerve around? Just because I can't seem to see something, doesn't mean it isn't really there.

So it is with Suzie. She can only launch out confidently if she knows two things: that I'm still attached to her at the end of the leash and that I know where we're going.

The same with the Lord; thanks be to God.

July 21, 2011

Life with a Blind Dog–How Come She's Always Hungry?

It seemed to come on quickly. From the time I first questioned whether she might be having a seeing problem to her diagnosis–two days.

But in hindsight, it crept up and fooled us for a good three months before the dog opthamologist (who would have guessed we have two in Sonoma County?) pronounced her stone-cold blind.

How could I not have suspected? Why didn't I realize I was a seeing-eye person? I'd only been walking the dog routinely for nine years. How could she maneuver around things so efficiently if she couldn't see?

I'll never know. But as soon as she was diagnosed it was all downhill and suddenly she couldn't even find her food dish without spilling the water and stumbling over her feet.

Though that did explain in part why she had gotten so fat–she couldn't run confidently so she didn't. The vet and I had discussed and tested her for her weight gain (15 pounds on a 39 pound dog over four months?) but somehow neither one of us realized she couldn't see until she walked into the wall instead of stepping through the sliding glass door. We think the blindness was caused by Cushing's Syndrome.

"As long as you don't mind owning a fat blind dog, she doesn't care," my niece, another veterinarian, explained. "A dog's principal sense is smell and then hearing. Seeing is the third most important sense, so just love her and take care of her and she should be perfectly happy."

Gordon Setters are notorious actors and they know how to exploit their owner's emotions, so while I'm sympathetic to her plight, I can't become a push-over either. Even while she insists she is starving to death and mopes around her food dish, I must remain firm. One cup of food in the morning, one in the evening. That's it. Even if she is blind.

Cushings affects her appetite; it seems to be affecting her more than the blindness. She's become a ravenous scarfer.

She wants more. She thinks she deserves more. She doesn't understand why we won't feed her more often. After all, she's handicapped isn't she? Don't I feel sorry for her? She keeps close track of the clock (how?) and knows when it's dinner time.

And if I don't get with the program, she sneaks down the hall and eats the cat food. Or finds her way to the cat litter and eats worse.

This all from a dog who rarely got around to finishing her food in one day the first nine years we owned her; who didn't care if other dogs came to visit and ate her kibble.

Suddenly, we can't leave anything on the counter–weren't those chocolate chip cookies for her? One day she climbed on the kitchen table and ate my tuna sandwich while my back was turned. What's that all about?

And I'm not going to tell you what happened when we spread chicken manure on the flower beds . . .

Her sense of smell drives her. That's where her pleasures lie these days. But the more she eats, the more she gains, the more ungainly she becomes. The stairs have become difficult and I have to lift her into the car when we go for a ride.

The object lesson for me is clear–a handicap in one area does not excuse poor behavior in another. Just because something bad happens to me, for example, doesn't mean I can lose my temper when I'm crossed by someone else. Or, just because I've had a hard day, doesn't mean I can eat all the chocolate chip cookies.

I'm watching Suzie closely. Not just to take care of her needs, but to find out what else I need to know about living with my wants.