Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 20

March 16, 2021

On Shadow Craft, a book about the aesthetics of black-and-white Hindi cinema

(Did this review – for Biblio: A Review of Books – of a cinema book I enjoyed quite a bit)

--------------

For anyone who loves black-and-white cinema – and also likes the idea of a creative work being encountered in its original form rather than disfigured to meet contemporary tastes – the computer-colourisation of old films is cause for teeth-gnashing. Almost equally bad is the current trend, on Instagram and elsewhere, of colourising old photos, such as publicity shots or candid stills of 1940s and 1950s movie stars – and doing this garishly, with little respect for the integrity of the original.

The idea that black-and-white cinema had its own visual grammar, that it wasn’t just a case of creativity being constrained by technology, remains surprisingly hard to grasp for many of today’s film students (this reviewer once had a teaching experience involving a student who said black-and-white images in old films literally made his eyes hurt). At purely a conceptual level, then, Gayathri Prabhu and Nikhil Govind’s visual study of some key Hindi films made between 1948 and 1963 is a very welcome project. Happily, Shadow Craft turns out to be more than just a worthy idea: this is an invigorating cinema book that is serious and detailed without being dense or inaccessible. Assuming, of course, that the reader has an appetite for intense subtextual analysis.

The idea that black-and-white cinema had its own visual grammar, that it wasn’t just a case of creativity being constrained by technology, remains surprisingly hard to grasp for many of today’s film students (this reviewer once had a teaching experience involving a student who said black-and-white images in old films literally made his eyes hurt). At purely a conceptual level, then, Gayathri Prabhu and Nikhil Govind’s visual study of some key Hindi films made between 1948 and 1963 is a very welcome project. Happily, Shadow Craft turns out to be more than just a worthy idea: this is an invigorating cinema book that is serious and detailed without being dense or inaccessible. Assuming, of course, that the reader has an appetite for intense subtextual analysis.

As the authors put it in their Introduction, the period they cover involves films that were watched by "the last generation that would not ‘see’ black and white as an absence of colour but as an assertive elaborate palette of textures, of intricate filigrees of dappled light, of deep tones of shadows, a complex vehicle to capture human interiorities and frailties at their nuanced best". Having made this strong claim for black and white filmmaking, they set out to justify it by closely examining specific sequences. After starting with Kamal Amrohi’s Mahal (1949) – billed as Hindi cinema’s first major ghost story – they turn to the three filmmakers who are generally regarded the most important Hindi-film auteurs of the 1950s: Raj Kapoor, Bimal Roy and Guru Dutt.

Major works such as Dutt’s Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool, Roy’s Bandini and Sujata, and Abrar Alvi’s Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam are discussed, but so are lower-profile films such as the 1955 Seema (a Nutan-starrer that prefigured her acclaimed roles with Bimal Roy and offered a pointer to how a more skilled director might use her distinct screen presence). Even when it comes to the big names, some of the choices made are pleasingly atypical. For instance, it would be easy to discuss the many striking scenes in a well-known film like Awaara (1951), such as the elaborate dream sequence used to represent the protagonist’s desires and fears. Instead, the authors go back a few years to look at Raj Kapoor’s first directorial venture, the less polished, less-seen Aag (1948), for hints of thematic and formal signatures to come.

Along the way, there are insights about framing, camera placement and movement, the use of foreground and background in set design – and as the book’s title (as well as its powerful cover image from Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam) suggests, much discussion of the interplay of light and shadow. This is particularly relevant in the context of black-and-white Indian cinema because, for a long time after colour became the norm, Hindi films were content to forego visual nuance; most directors lit every corner of the frame to make a film as bright and colour-drenched as possible.

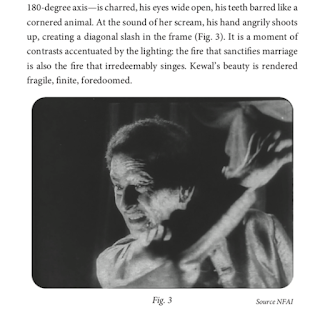

Of course, no serious discussion of a film’s aesthetics can be about the use of light and shadow in isolation; when watching a well-constructed film, one finds form and content working in conjunction, many elements coming together in barely perceptible ways to create the entirety of a scene. Accordingly, the insights provided by this book are many and varied. Discussing the opening sequence of Mahal, for example, the authors describe the shot where a gardener pulls at a chain to lift a chandelier to the ceiling and the camera simultaneously tracks in to show the face of the protagonist (played by Ashok Kumar) for the first time. The moment represents a familiar trope of Hindi cinema, the stylised reveal of a star-actor; but in this case, given what has come before in the sequence, it also marks “an obscuration between the corporeal and the shadowy, the living and the dead”. Similarly, the Aag chapter dwells on the many meanings of the film’s title (“the fire that sanctifies marriage is also the fire that irredeemably singes”), Raj Kapoor’s use of a theatre’s proscenium as “a mystery space full of unsuspected and obscure aural depths”, the tension between stage and cinema that may be found in this first film, and the foreshadowing of elements in later works like Mera Naam Joker and Satyam Shivam Sundaram. The Nutan-Bimal Roy chapter analyses pivotal visual moments such as the rain scene in Sujata where the protagonist contemplates suicide, and the scene in Bandini where she is driven to murder; but also discusses in more general terms how Nutan “performs with her entire body” and expresses rage, and how Roy “restores the actor’s centrality by keeping the props to a minimum, both in terms of the horizontality of the frame as well as its depth”.

Similarly, the Aag chapter dwells on the many meanings of the film’s title (“the fire that sanctifies marriage is also the fire that irredeemably singes”), Raj Kapoor’s use of a theatre’s proscenium as “a mystery space full of unsuspected and obscure aural depths”, the tension between stage and cinema that may be found in this first film, and the foreshadowing of elements in later works like Mera Naam Joker and Satyam Shivam Sundaram. The Nutan-Bimal Roy chapter analyses pivotal visual moments such as the rain scene in Sujata where the protagonist contemplates suicide, and the scene in Bandini where she is driven to murder; but also discusses in more general terms how Nutan “performs with her entire body” and expresses rage, and how Roy “restores the actor’s centrality by keeping the props to a minimum, both in terms of the horizontality of the frame as well as its depth”.

Finally, the segment of the book that can be seen as centred on Guru Dutt (Abrar Alvi, the director of Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, acknowledged that Dutt had helmed the film’s song sequences) examines cinematographer VK Murthy’s use of very low light readings for Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool (“this technical choice explains several frames in both the films that feel like they have barely enough light for the human eye to see and for the silver nitrates on the frame to register”), the notable use of dissolves in Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, and the subtlety with which a song sequence – where Bhoothnath (Dutt) hears Choti Bahu (Meena Kumari) singing from a distance – “turns aurality into a visual semiotic”. The analyses are complemented by still images from the sequences in question – and the story of how the authors acquired these images from the original prints sourced through the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) is related by Prabhu in a poignant “Outro”. However, Prabhu and Govind are also upfront about the “deception involved in reducing movement to stillness” – that is, the limitations of a printed book in conveying the special impact of watching a live film unfold before your eyes.

The analyses are complemented by still images from the sequences in question – and the story of how the authors acquired these images from the original prints sourced through the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) is related by Prabhu in a poignant “Outro”. However, Prabhu and Govind are also upfront about the “deception involved in reducing movement to stillness” – that is, the limitations of a printed book in conveying the special impact of watching a live film unfold before your eyes.

Which is a reminder, for potential readers, that any meaningful engagement with this book must entail experiencing the films too. This can mean extra effort, but the results should be rewarding for any cinephile. This reviewer found himself a little lost reading the first few paragraphs of the Mahal analysis, for instance, but things changed completely after an online viewing of the opening sequence. So it is for the rest of the films, and the journey should be enlightening even for those who think they know a particular classic inside out.

When one talks about watching old films with any seriousness or attention to detail, the question inevitably arises: how to watch these films, in what condition, what prints? In the aforementioned Outro, Prabhu mulls the importance of preserving original prints, seeing frames the way they were meant to be seen (“watching the 35 mm film, I found that the eye travelled on the image differently and one revelled in the elegance of the 4:3 dimension, rather than the more prevalent widescreen ratio of 2.35:1”), and frets about a fungus-affected reel of Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, which may or may not be salvaged. This reminder of the fragility of old films underlies the whole book, and is echoed in the poignant story about VK Murthy, master of shadows, saying after Guru Dutt’s death, “I did not cry for him. I cried for myself.”

March 13, 2021

50 years of Anand: a tribute

(Wrote a short tribute to Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Anand on its 50th anniversary, for the Sunday Times of India. My appreciation for the film has deepened over the years -- I didn’t gush about it when I wrote the book -- and I think it’s easier to see now why so many people think of it as Hrishi-da's definitive work.

(Wrote a short tribute to Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Anand on its 50th anniversary, for the Sunday Times of India. My appreciation for the film has deepened over the years -- I didn’t gush about it when I wrote the book -- and I think it’s easier to see now why so many people think of it as Hrishi-da's definitive work.Here’s the piece, in case the text in the image isn't clear)

Everyone who loves Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anand agrees that it is one of the warmest, most life-affirming of Hindi films. As it turns fifty, the dominant memory is of the terminally ill hero, played by Rajesh Khanna, spreading cheer and inspiration, determined to live a badi zindagi (big life) even if he isn’t fated for a lambi (long) one.

But here’s a reminder – for those who have only a highlights-reel memory of Anand – of the deep darkness that underlies this story. Early in the film, Dr Bhaskar (Amitabh Bachchan) is trying to heal slum-dwellers but feeling increasingly hopeless about an unending cycle of poverty and misery. Shortly after he has pronounced a patient beyond help, an old woman comes up with mithaai for him; her grandchild has just been born. The celebratory sweet still in his mouth, Bhaskar thinks to himself: “Ek mara nahin, aur doosra paida ho gaya marne ke liye!” (“One hasn’t died yet, and another has been born to suffer the same fate.”)

The words, spoken in Bachchan’s intense, caustic tone, are startling, almost a punch to the gut. But they become even more so when one considers this: Hrishikesh Mukherjee – avuncular high priest of the Middle Cinema, maker of so many gentle films whose very titles make viewers smile – this same “Hrishi-da” closely identified with Bhaskar’s pessimism. In an interview once, he cuttingly said, “I have always believed that the power of evil is far stronger than the power of good. A tiny drop of poison can ruin a bucket of milk.” Discussing the genesis of Anand, which he first wrote as a novella before getting it converted into a screenplay, he often spoke about how it was based on his friendship with Raj Kapoor, who was the ray of sunshine in his life (or perhaps the antidote to poison), much the same way Anand would brighten Bhaskar’s horizon.

The film’s initially downbeat, Bhaskar-dominated tone changes quickly when Anand shows up, bursting through a door as chirpy, star-heralding music plays. (The Raj Kapoor homage is inescapable, especially if you have watched “Kisi ki Muskurahaton Pe” from Hrishi-da’s Anari.) What follows are a series of heart-warming vignettes, punctuated by lovely songs – and only a few sad moments that aren’t allowed to linger. Anand’s own attitude, as buoyant as the balloons he releases into the sky at the start of “Zindagi Kaisi hai Paheli”, is what the film constantly emphasizes.

Two years earlier, Mukherjee had made a darker film, Satyakam, which he always cited as his personal favourite – even holding its box-office failure as evidence of its refusal to provide easy sops to a mass audience. Watching these two films – which have a few structural similarities – back to back can be revealing. If Anand is like nourishing broth on a winter’s night, Satyakam – about an uncompromising man who is repeatedly disappointed by an imperfect world – can feel a bit like biting into a lemon. (Imagine what Anand would be like if Dr Bhaskar had been its protagonist and Anand never came through that door.)

Satyapriya, the hero of Satyakam, and Dr Bhaskar are both Serious Men, weighed down by unflinching idealism which turns to cynicism and despair. They are also unimaginative and rigid, prone to seeing the world in black and white. And they have little patience for fantasy or make-believe – qualities that were vital to the Hrishikesh Mukherjee universe, which is so often about the healing power of masquerade or naatak.

Hrishi-da may have defensively viewed Satyakam as a more serious, hence better, film than his box-office hits, but “popular” doesn’t have to mean unserious. And it is significant that the best-loved and most enduring Hrishikesh Mukherjee films today – with Anand first among them – are the ones that have the widest ranging view of human nature and a sense of fun. Like Ram Prasad in Gol Maal and Professor Parimal Tripathi in Chupke Chupke, Anand Sehgal understands the importance of those qualities. He knows that for zindagi to be “badi”, one should experience it in all its dimensions: be flippant, crack goofy jokes with the nurse who is trying to get you to rest, do silly things like accost strangers and address them familiarly (until you find that one person who is willing to play along); recognise that we are all “rangmanch ke kathputli” (puppets on life’s stage), and that each man in his time must play many parts.

My appreciation for Anand has grown with time: watching it on a big screen once with a hall full of enthusiastic fans, I found myself more invested in the central character, and in Khanna’s charismatic star presence which must have had such a huge impact in 1971. But increasingly, I also feel that in Dr Bhaskar’s journey over the course of the story one sees Hrishi-da locating his own inner Anand and engaging in a form of self-healing – by making a film that manages to be breezy and meaningful, playful and profound at the same time.

March 9, 2021

On Basu Bhattacharya's Anubhav: Middle Cinema, meet avant-garde

[the latest in my First Post column about establishing sequences; this is about the first film in Bhattacharya's 'marriage trilogy']

--------------------

It begins like a party scene that could have come out of any number of Hindi films of the 1960s or early 70s. A hostess in an elegant saree. Liveried servants bearing plates of snacks and cold drinks. A dining room packed with guests, many of whom are clearly played by “extras” (a couple of them glance self-consciously in the direction of the camera). There is even AK Hangal doddering around as the family retainer, one of the staple sights of a certain sort of cosy Hindi film of this period.

Keep watching, though, and you’ll realise that this early scene in Basu Bhattacharya’s Anubhav (1971) employs a language very different from most other narrative Hindi films of the time. A sense of disarray is created by the use of overlapping dialogues – rare in our cinema, though the American director Robert Altman was doing notable things with this technique around the same time – and naturalistic sound. A handheld camera follows a little child as he drifts about the crowded room looking confused and lost, negotiating a melange of sights and conversations. Much like the viewer.

We might have been prepared for this by the film’s opening two minutes, just preceding this scene, where there is a deliberate mismatch between visual and soundtrack. First, over shots of the Bombay seascape, we hear a phone conversation between two people in which a “marriage anniversary party” is mentioned. Then we see extreme closeups of a woman’s eyes, lips, ears, forehead, fingers, as she applies makeup and jewellery. This is Meeta Sen (Tanuja) getting ready for the party she is hosting with her husband Amar (Sanjeev Kumar), but no easy cues are provided to the viewer at this point (the aural accompaniment to this scene is another phone conversation between two people whom we won’t even meet).

We might have been prepared for this by the film’s opening two minutes, just preceding this scene, where there is a deliberate mismatch between visual and soundtrack. First, over shots of the Bombay seascape, we hear a phone conversation between two people in which a “marriage anniversary party” is mentioned. Then we see extreme closeups of a woman’s eyes, lips, ears, forehead, fingers, as she applies makeup and jewellery. This is Meeta Sen (Tanuja) getting ready for the party she is hosting with her husband Amar (Sanjeev Kumar), but no easy cues are provided to the viewer at this point (the aural accompaniment to this scene is another phone conversation between two people whom we won’t even meet).

In fact, the first indication Anubhav provides of settling down and focusing on one of its protagonists is in the post-party scene where Meeta sits contemplatively on her bed, next to the now-sleeping child. But even here, the stylistic decisions are precise and significant: the sound of a clock ticking in the background, which will become one of the film’s running motifs (this is, among other things, a story about time and how we use it), the way the camera freezes on Tanuja’s face as the opening credits begin, with “Anubhav” written in Devanagari multiple times across the screen. Even the placement of the names of the three main actors is telling.

It all looks a tad “arty”, but it perfectly establishes the film’s mood and aesthetics.

Anubhav was the first film in what became known as Bhattacharya’s marriage trilogy (it was followed by Avishkaar and Griha Pravesh). What is it “about”? A six-year-old marriage that has stagnated because Amar, a prominent newspaper editor, is too busy with work… and, well, because married couples often take each other for granted in a way that they don’t do with their other relationships. Meeta tries to rectify this state of affairs (starting with downsizing their domestic staff so that the place becomes less like a hotel and more like a home) – but things get complicated when her former boyfriend Shashi (Dinesh Thakur) shows up and becomes one of Amar’s prized employees.

That sounds like a solid plot, but it isn’t enough to discuss this film only in terms of story or what it has to say about marriage, companionship and loneliness – or by focusing on the dialogue and performances. All those things are important, of course (without Tanuja’s excellent performance in the central role, the film would be diminished), and one can’t underestimate the frankness of Bhattacharya’s depictions of intimacy between two people who have lived together for years (even when there is a fracture in their relationship). Scenes like the one where Meeta gets out of bed after extricating herself from the sleeping Amar’s hold and reaching behind her pillow for the blouse that was unloosened the night before, or the one in Avishkaarwhere Mansi (Sharmila Tagore) and another Amar (Rajesh Khanna) fool around in the bathroom together, may be the closest that 1970s mainstream (or semi-mainstream) Hindi cinema came to the quotidian, lived-in feel of the sex scene between a married couple in Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973).

That sounds like a solid plot, but it isn’t enough to discuss this film only in terms of story or what it has to say about marriage, companionship and loneliness – or by focusing on the dialogue and performances. All those things are important, of course (without Tanuja’s excellent performance in the central role, the film would be diminished), and one can’t underestimate the frankness of Bhattacharya’s depictions of intimacy between two people who have lived together for years (even when there is a fracture in their relationship). Scenes like the one where Meeta gets out of bed after extricating herself from the sleeping Amar’s hold and reaching behind her pillow for the blouse that was unloosened the night before, or the one in Avishkaarwhere Mansi (Sharmila Tagore) and another Amar (Rajesh Khanna) fool around in the bathroom together, may be the closest that 1970s mainstream (or semi-mainstream) Hindi cinema came to the quotidian, lived-in feel of the sex scene between a married couple in Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973).

However, what Anubhav does with its visuals and sound design are just as central to its effect, making it one of the most distinctive Hindi-film experiences of its time. There is also a playfulness that might not be apparent to a first-time viewer, since this is on the face of it such a “serious” film. In one scene between Amar and Shashi, they talk about Bertolt Brecht, and shortly afterwards Sanjeev Kumar gets a little moment – when Amar has an epiphany about his wife – where he delivers his lines using the detached Brechtian method, repeating phrases over and over in a descriptive rather than an emotionally expressive way.

*****

During a recent online session about Hrishikesh Mukherjee and the Middle Cinema, I was asked a question about why the “middle-class” directors of the 70s seemed so uninterested in doing avant-garde things. I was reminded of what the filmmaker Kumar Shahani once said about interviewing Mukherjee:

“Hrishi-da was always very knowledgeable about technique and theory, so I asked why he didn’t do more experimental things despite the fact that he knew so much about cinema. And he got a little defensive and said ‘Kumar, please be kind to me! You know we can’t do that beyond a point in our milieu’. ”

There is a different debate to be had about how intelligent stylistic choices can subtly be made even in a straightforward narrative-driven film – and how “visually interesting” doesn’t have to be synonymous with “showy”. But for now, let’s ask a more specific question: what might the Middle Cinema of the 1970s have looked like if its directors had channelled the spirit of the many global cinematic New Waves of the time, the work of directors like Godard or Menzel or Fellini, instead of opting for a version of the tele-serial aesthetic? What if these films had been full of rapid cuts, unexpected zoom-ins and zoom-outs, lengthy held shots, or the use of surrealism to convey a character’s inner conflicts?

An answer to this question may be found in selected sequences from some popular films of the time, such as the nightmare of dislocation that opens Basu Chatterjee’s Rajnigandha (1974) – Vidya Sinha in a lovely blue saree (what could be more representative of Indian middle-class cinema!) waking to find herself alone on what seems like a ghost train, and then stranded at a desolate railway station. Or the proto-MTV-like whip zooms and extreme close-ups used in the “Rail Gaadi” scene in Mukherjee’s Aashirwad. Or in a few scattered films that were clearly keen to push the boundaries of cinematic form: Chatterjee’s 1969 debut Sara Akash, Awtar Krishna Kaul’s one-off 27 Down (1974). But Anubhav is perhaps the most fully realised work of this kind.

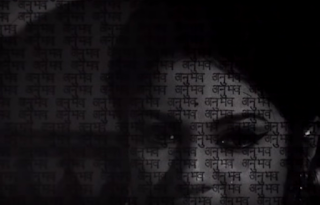

It is unconscionably late in this piece to mention this, but much of the film’s visual impact comes from the decision to shoot it in black and white – at a time when colour was very much the norm, even for low-budget films. Nando Bhattacharya’s camerawork superbly justifies this decision, making many scenes look moody and noir-ish. Much attention has been directed at the delicate picturization of the song “Meri Jaan Mujhe Jaan na Kaho” (one of Geeta Dutt’s last major works as a singer), but there is also “Mera Dil jo Mera Hota”, a wonderfully constructed sequence that was essentially put together in the editing.

In this scene, as Meeta bathes, vignettes from her newfound happiness with Amar flash through her mind, and both sets of images – the here and now, in the bathtub, and the day-dream that encompasses many other places and times – blend. Dissolves, superimpositions and shadowy juxtapositions are carefully employed: at one point, the shower in the bathroom seems to be raining down water on an image of Amar and Meeta as they appear in her mind’s eye. This device also allows Bhattacharya to suggest risqué moments – kissing, lovemaking – without actually showing them directly.

In this scene, as Meeta bathes, vignettes from her newfound happiness with Amar flash through her mind, and both sets of images – the here and now, in the bathtub, and the day-dream that encompasses many other places and times – blend. Dissolves, superimpositions and shadowy juxtapositions are carefully employed: at one point, the shower in the bathroom seems to be raining down water on an image of Amar and Meeta as they appear in her mind’s eye. This device also allows Bhattacharya to suggest risqué moments – kissing, lovemaking – without actually showing them directly.

It’s a fine example of the coming together of what is “actually” happening and the heightened reality of the inner world. The scene allows a viewer to be directly plugged into Meera’s experience – or anubhav – and creates a sense, vital to the film’s purpose, of how tenuous and shadowy our relationships can be. With hindsight, it also adds to the impact of that early scene with the many little “anubhavs” printed across the screen as she sits by herself, reflecting.

[Earlier First Post columns are here]

<font size="4"><span style="font-family: verdana;">@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</span></font>

March 4, 2021

Film-club discussion: Macbeth via Welles, Kurosawa, Polanski, Bhardwaj

My online film-club discussions were on hold the past few weeks, since I was busy with the Hrishikesh Mukherjee course, but I’m planning to re-ignite them with a (very informal and free-flowing) conversation about different adaptations of Macbeth. It is fun to compare the many treatments of some of the play's most famous scenes: the witches' prophecies, the "dagger of the mind", the appearance of Banquo's ghost, Lady Macbeth's hand-washing, and of course the finale with the forest coming to Macbeth's castle (or, as in Vishal Bhardwaj's Maqbool, the "dariya" coming to Maqbool's home).

My online film-club discussions were on hold the past few weeks, since I was busy with the Hrishikesh Mukherjee course, but I’m planning to re-ignite them with a (very informal and free-flowing) conversation about different adaptations of Macbeth. It is fun to compare the many treatments of some of the play's most famous scenes: the witches' prophecies, the "dagger of the mind", the appearance of Banquo's ghost, Lady Macbeth's hand-washing, and of course the finale with the forest coming to Macbeth's castle (or, as in Vishal Bhardwaj's Maqbool, the "dariya" coming to Maqbool's home).Anyone who’s interested in the discussion, or even in just watching the films, please email me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) and I’ll send across prints of Orson Welles’s Macbeth (1948), Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957) and Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971). (I am particularly glad to finally have a good print of the Welles version. Thanks to my friend Michael Enright for that.)

<font size="4"><span style="font-family: arial;">@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</span></font>

February 28, 2021

A book about Bombay's 'cine-ecology' in the early years of the sound film

(Did this very short review – for India Today – of the new academic book Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City. Much more to be said about this diligently researched book than can be covered in a 450-word piece; I’ll try to share a few short excerpts soon.)

(Did this very short review – for India Today – of the new academic book Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City. Much more to be said about this diligently researched book than can be covered in a 450-word piece; I’ll try to share a few short excerpts soon.)In one of the more engaging chapters of this book about Bombay’s “cine-ecology”, Debashree Mukherjee examines the larger significance of the hunger strike by the actress Shanta Apte against Prabhat Studios, Poona in 1939. Part of what Apte was protesting was the de-humanisation of the cine-worker, treated as no different from inanimate machinery. “Exhaustion / Thakaan” is the chapter title, and in a recent online promotional event Mukherjee mentioned two key words that help denote how film work is different from other kinds of work: exhaustion and waiting. Waiting to be called, waiting for lighting, waiting outside a vanity room.

The Apte story is just one of many sub-narratives that make up this wide-ranging academic work, which studies Bombay cinema as a site of production – focusing on the industry as it developed between the “transitional” period spanning the late 1920s to the early 1940s. Bombay Hustle is divided into two parts: the first is a macro view of the industry – the organisational efforts, the financing, the technical practices – while the second is a more intimate view, focused on the bodies and energies that flow through the world of film production. How did Bombay become such a pre-eminent film centre? When did work practices and aesthetics start to crystallise into the things we recognise (and even take for granted) in the industry of today? These are among the book’s foundational questions.

In addressing them, it discusses the vital early link between the industry and speculative trade in the cotton futures market (via the stories of colourful figures such as Ranjit Movietone founder Chandulal Shah, who put gambling profits into his films); the role of the mill-workers who were among the earliest, most enthusiastic viewers; the idea of the “public woman” as a marker of Bombay’s modernity, and the phenomenon of the once-very-popular “abhinetri films” which argued that women had the right to work with dignity and safety as actresses (and often accommodated a modern and traditional vision at once).

It’s obvious that in choosing this subject and period, Mukherjee didn’t take the easy route. Whenever there are references to specific films and personalities (along with some evocative and intriguing promotional images), one is sadly reminded that the vast majority of films made during this period are lost. So is enormous amounts of archival material. Given this, the magnitude of the research involved here is admirable.

The writing itself is not always easy to get through, especially for the non-academic reader. For me, personally, some of the content felt repetitive and abstract, and the more stirring sections were the ones about the experiences of specific people – including when the author places herself in the text, discussing her experiences as an assistant director in the early 2000s and reflecting on how the term “Struggle jaari hai” has applied equally to cine-workers living a century apart. Or how, when she was returning home late one a night, “a street corner awash in yellow tungsten light felt like a film set”, and cinema and the city seemed to merge into one.

February 7, 2021

The eye of the artist: on Roger Corman’s A Bucket of Blood and The Little Shop of Horrors

(the second entry in my “establishing sequences” column for First Post – this one about a low-budget 1950s genre film that offers a chilling, and funny, view of creative people as entitled predators)

--------------------

“I will talk to you of Art.”

Those are solemn opening words for any film, and they are intoned by a solemn, bearded man who is looking straight at the camera from behind the opening credits. The camera draws back, as if startled into retreat, and the man – soon to be revealed as a Beat poet reciting at a club – continues his portentous verse to the accompaniment of a trumpet solo.

“For there is nothing else to talk about.

For there IS nothing else.

Life is an obscure hobo, bumming a ride on the omnibus of art.”

On that last line – which can sound goofy or profound, depending on the mood you’re in – the film’s protagonist enters the frame. Walter Paisley, an obscure hobo if there was one, is serving food and drinks at nearby tables, watching the poet, fascinated by the recital. As the credits (and the poem) end, Walter is at the table of the girl he fancies, looking at a  drawing she has made. “What kind of people do you like, Carla?” he will ask her later. “Thinking people, I guess,” she drawls. “Artistic people.”

drawing she has made. “What kind of people do you like, Carla?” he will ask her later. “Thinking people, I guess,” she drawls. “Artistic people.”

Roger Corman’s 1959 film A Bucket of Blood will turn out to be a wry comment on the idea that artists – “thinkers” – are superior to other, “ordinary” people. But to describe this film primarily in such terms might be pretentious. Because this is, first and foremost, an entertaining and fast-paced B-movie, a horror-comedy made by Corman and his writer Charles B Griffith on a tiny budget in just five days.

Only then is it also an unusual and intriguing look at the parasitic relationship between a creative person, his subjects, and his audience.

Artistic recognition will come to Walter in macabre circumstances, after he accidentally kills a cat and then covers it with clay to make a “sculpture”. But once the spiral of fame begins, he finds that he is addicted to it. “What am I going to do next?” this confused young man asks himself at one point, “I’ve got to do something before they forget. I know what it’s like to be ignored.”  It’s the fear of every insecure artist: that the last thing you did – however well-received it might have been – will be forgotten very soon and you need to find a way to stay relevant. Speaking those words, Walter could be a writer or filmmaker hoping to reach out to a younger audience, fearful that they might think his work dated (or that they might even be unaware of it); or a painter keeping a worried eye on new movements that might make his accomplishments seem quaint. His art demands sacrifice, Walter realises – not only from him but from others too.

It’s the fear of every insecure artist: that the last thing you did – however well-received it might have been – will be forgotten very soon and you need to find a way to stay relevant. Speaking those words, Walter could be a writer or filmmaker hoping to reach out to a younger audience, fearful that they might think his work dated (or that they might even be unaware of it); or a painter keeping a worried eye on new movements that might make his accomplishments seem quaint. His art demands sacrifice, Walter realises – not only from him but from others too.

****

But back to that opening sequence, which establishes the film’s mood – its strange mix of the languid and the urgent – and foreshadows what will happen in the story. The Beat poet, Maxwell, drones on about artists as exalted beings.

“Let them become clay in his hands, that he might mould them,” Maxwell says, “Stretch their skins upon an easel to give him a canvas. Crush their bones into a paste.”

For all that is comes through the eye of the artist. The rest are blind fish swimming in the cave of aloneness. Swim on, you maudlin, muddling, maddened fools, and dream that one bright, sunny night the artist will bait a hook and let you bite upon it. Bite hard, and die. In his stomach you are very close to immortality.

Incidentally, having watched the film with subtitles enabled, I felt it was useful to be able to “read” the poem at the bottom of the screen as one heard it. It’s likely that many people who watched A Bucket of Blood during its initial run missed the import of this scene. Apart from the fact that you don’t expect such intense verbal imagery from a B-movie of this sort, in those days the part of a film that played while the credits were still running was easily dismissed as not being vital to the narrative. (In 1950s America, there was also the bizarre tradition of people sauntering in to watch a film at any point, with little respect for show timings.) So this could be a case where subtitles – used even where the viewer has no trouble understanding the dialogue – can add a dimension to a scene, encouraging us to pay attention.

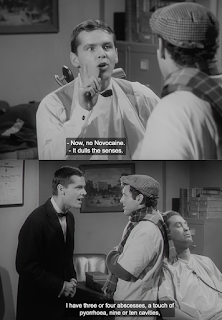

A year later, in 1960, Corman and Griffith made a better known horror-comedy, The Little Shop of Horrors, a delightfully weird story about a florist-shop employee tending to a bloodthirsty plant. It’s a film full of manic humour, including goofy non-sequiturs, neologisms (“It’s monstrositive!”) and malapropisms (“it’s a finger of speech!”); the oddball characters include a customer who likes to eat flowers, and two detectives who have impossibly terse exchanges; and there is a short appearance by the 23-year-old Jack Nicholson (the Satanic grin of the future already plastered on his face) as a masochist who visits a dentist hoping for pain.

A year later, in 1960, Corman and Griffith made a better known horror-comedy, The Little Shop of Horrors, a delightfully weird story about a florist-shop employee tending to a bloodthirsty plant. It’s a film full of manic humour, including goofy non-sequiturs, neologisms (“It’s monstrositive!”) and malapropisms (“it’s a finger of speech!”); the oddball characters include a customer who likes to eat flowers, and two detectives who have impossibly terse exchanges; and there is a short appearance by the 23-year-old Jack Nicholson (the Satanic grin of the future already plastered on his face) as a masochist who visits a dentist hoping for pain.

The structural similarities between A Bucket of Blood and The Little Shop of Horrors are obvious: each deals with an awkward young man who, initially through circumstance rather than intent, becomes a celebrity in his social circle, and then finds that building on this popularity requires crossing an ethical line (to put it mildly).

While The Little Shop of Horrors is probably a funnier film on the whole, the grim – even unpleasant – humour of A Bucket of Blood is surprisingly effective too, as Walter goes from genuine regret (about the provenance of his first couple of sculptures) to becoming seduced by praise; the need for creative validation quickly overcomes other considerations. (“Let it all crumble to feed the creator,” intones Maxwell during that opening poem; one is reminded of Audrey the insatiable plant in The Little Shop of Horrors.)

Just as notable is A Bucket of Blood’s depiction of various aspects of the Beat culture of the time: the endearing idealism, the casual chatter about organic food and wheat germ oil, the “groovy” exclamations like “Too much” and “Man, we have to make this scene”. And the pretentiousness of a certain type of intellectual manque. It’s easy to see why the sage-like Maxwell is a revered figure in club circles, but as the story progresses his impressiveness wears off to reveal something more banal (much like the clay wears off Walter’s creations at inopportune times).  For instance, in a late scene, Maxwell, noting the public interest in Walter’s sculptures, says: “You could get 25000 on these pieces alone.”

For instance, in a late scene, Maxwell, noting the public interest in Walter’s sculptures, says: “You could get 25000 on these pieces alone.”

“I thought you put money down,” Walter replies.

“I do!” Maxwell says, looking more animated than we have ever seen him before, “But 25000?!” Here he is, the high-minded poseur scoffing at materialism only as long as the reward isn’t too tempting.

1959 and 1960 were years when major filmmakers around the world were doing some of their best work, and this was also a key period for the horror genre. A Bucket of Blood came a year before Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, in which a disturbed young photographer’s quest for a “perfect” image of fear leads him toward murder as a sort of art form. Peeping Tom was denounced as an “evil” or “immoral” film by many contemporary critics, but even those reactions indicated that people took the film (and its director) seriously enough to be offended, or scared about its impact. Roger Corman’s films were rarely given that much importance; they were treated as second-rate fare that didn’t need to be seriously reviewed, and which wouldn’t reach respectable viewers anyway. But that’s an injustice to a film like A Bucket of Blood. It isn’t as polished or as well-crafted as Peeping Tom – or some of the other seminal horror films of the time, like Hitchcock’s Psycho – and it suffers from its budgetary limitations. (For instance, the final shot – I won’t reveal what it is – could have been much more effective, and poetic, with better makeup or more time.) But it has its own special strengths, and sly things to say about both a particular subculture and about artists in general. In the end, it lives up to that promise made in its opening declaration.

[Earlier First Post columns - on literature and cinema - are here]

January 12, 2021

Well begun: two princes and a mischievous God in Maya Bazar

I have started a new column for First Post, which centres on opening scenes (or establishing sequences). The first entry is about a film that I properly discovered while preparing for the online Mahabharata course that Karthika Nair and I taught a few months ago: the 1957 Maya Bazar, a magnificent musical-comedy-fantasy that is as good as anything Indian cinema gave us in that very important decade. I still revisit its songs often on YouTube, especially “Aha Naa Pelliyanta”, which has Savitri’s superb performance as Ghatotkacha disguised as a princess, and "Vivaha Bhojanambu” (which borrows its tune from the music-hall classic "The Laughing Policeman".

Here is the piece.

--------------------------

The opening credits begin, and you can tell that a period epic is about to unfold. But first there is a brief, mood-setting interlude: a confrontation between an earthbound archer and a burly, mace-wielding fellow in the sky. They launch their weapons; the arrow and the mace race towards each other and collide in mid-air, as these things tend to do in our mythological films.

And then the main title appears.

Maya Bazar. A few months ago, while teaching an online course about the Mahabharata, I re-watched KV Reddy’s magnificent 1957 film (made in both Tamil and Telugu), and was again enthralled – by the humour, the visual grandness, the music, the performances, the ceaseless sense of wonder. But I was also struck by that opening moment, which is a taster of an important later scene.

A few months ago, while teaching an online course about the Mahabharata, I re-watched KV Reddy’s magnificent 1957 film (made in both Tamil and Telugu), and was again enthralled – by the humour, the visual grandness, the music, the performances, the ceaseless sense of wonder. But I was also struck by that opening moment, which is a taster of an important later scene.

A viewer who doesn’t know about the plot of Maya Bazar might – on the basis of visual cues accumulated from other mythological films and TV shows, or the iconography of Amar Chitra Katha comics – conjecture what is going on here thus: the archer is the hero; the heavily moustached mace man (who slightly resembles the Ravana of the 1980s television Ramayana) is the antagonist; perhaps even a wicked asura.

But as it happens, these combatants are both the progeny of the heroic Pandavas, both destined to play key roles much later in the great epic. Abhimanyu, the son of Arjuna and Subhadra, has strayed into the enchanted realm of Ghatotkacha, the son of Bheema and Hidimbi. They don’t yet recognise each other, but when they do a joyous brotherly reconciliation will take place – and their mothers, one a Yadava princess, the other a rakshasi who rules over a forest, will greet each other as sisters. Like cousins going to a film together during the summer holidays, Abhimanyu and Ghatotkacha will even settle down to watch a stage performance of a famous Puranic story (the one about the asura who acquires the boon that he can destroy anyone by placing his hand on their head).

Shortly after this, Ghatotkacha will use his powers to help Abhimanyu reunite with his love Sasirekha – and this becomes the pretext for a delightful comedy involving action and impersonation and a lavish wedding feast.

All that comes later, though. The first narrative scene of Maya Bazar (after those opening credits) is set in Dwaraka, the abode of Lord Krishna, who is the other magician or “maya-vi” figure in this film. The early scenes will stress both the magic in the air (a box-shaped device, which can be opened to communicate with people who are far away, is like a bejewelled prototype for an online video-call) and Krishna’s divinity – most notably in a beautiful sequence that points to how he has been mythologised in his own lifetime. But these scenes are also about family politics, romance, and the casual chatter that takes place in everyday life, even when the people involved are legendary figures like Krishna or Balarama.

If you grew up watching Tamil or Telugu films anytime from the 1950s onward – or even had some knowledge of these cinemas – you would know Maya Bazar, and its towering reputation, in the same way that Hindi-film viewers know of Sholay or Mughal-e-Azam. Apart from its exceptional qualities as a musical-comedy-fantasy, it brings together some of the most notable names in south Indian cinema – starting with NT Rama Rao in the first (and possibly the most endearing) of his many performances as Krishna, and SV Ranga Rao as Ghatotkacha, who goes from being fearsome to childlike in the blink of an eye. The young Savitri is superb as the heroine Sasirekha (known as Vatsala in the Tamil version), particularly in the scenes where Ghatotkacha, disguised as the princess, shifts from daintiness to demoniac swagger and back again. And across the two versions of the film, the role of Abhimanyu is played by two major stars: Akkineni Nageswara Rao in Telugu and Gemini Ganesan in Tamil.

If you grew up watching Tamil or Telugu films anytime from the 1950s onward – or even had some knowledge of these cinemas – you would know Maya Bazar, and its towering reputation, in the same way that Hindi-film viewers know of Sholay or Mughal-e-Azam. Apart from its exceptional qualities as a musical-comedy-fantasy, it brings together some of the most notable names in south Indian cinema – starting with NT Rama Rao in the first (and possibly the most endearing) of his many performances as Krishna, and SV Ranga Rao as Ghatotkacha, who goes from being fearsome to childlike in the blink of an eye. The young Savitri is superb as the heroine Sasirekha (known as Vatsala in the Tamil version), particularly in the scenes where Ghatotkacha, disguised as the princess, shifts from daintiness to demoniac swagger and back again. And across the two versions of the film, the role of Abhimanyu is played by two major stars: Akkineni Nageswara Rao in Telugu and Gemini Ganesan in Tamil.

On the other hand, if you did not grow up with those languages and cinemas, you might go decades as a movie buff without knowing much about Maya Bazar. I was in my late thirties when I got to watch a good print with subtitles, and halfway through I knew I was in the presence of cinematic brilliance. For me it now ranks alongside any of Indian cinema’s finest achievements of that decade, from Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy to the best work of Guru Dutt, Raj Kapoor and Bimal Roy.

To some degree, this has to do with my Mahabharata-love; to be able to appreciate Maya Bazar in all its dimensions, one has to appreciate its fresh, whimsical slant on characters who are already familiar from the great epic. It is based on the folk-tale Sasirekha Parinayam, which had been filmed as far back as the 1930s, and the ways in which the story departs from the canonical Mahabharata are very telling.  For instance, it might seem strange to say that this is a comforting, heart-warming film, considering that in the mainstream Mahabharata both Ghatotkacha and Abhimanyu end up dying in tragic circumstances – it might even be said that both of them are sacrificed as a gambit by Krishna. (Ghatotkacha’s death is the one that is explicitly presented as a ploy – Krishna wants Karna to use his lethal weapon against the dispensable rakshasa rather than against Arjuna – but Abhimanyu’s killing also serves the function of harnessing Arjuna’s fury and raising the stakes and intensity of the war.) Watching the interaction of the central characters in Maya Bazar – especially the camaraderie between Krishna and Ghatotkacha – it is hard to imagine these same people in that distant, calculated scenario on the Kurukshetra battlefield.

For instance, it might seem strange to say that this is a comforting, heart-warming film, considering that in the mainstream Mahabharata both Ghatotkacha and Abhimanyu end up dying in tragic circumstances – it might even be said that both of them are sacrificed as a gambit by Krishna. (Ghatotkacha’s death is the one that is explicitly presented as a ploy – Krishna wants Karna to use his lethal weapon against the dispensable rakshasa rather than against Arjuna – but Abhimanyu’s killing also serves the function of harnessing Arjuna’s fury and raising the stakes and intensity of the war.) Watching the interaction of the central characters in Maya Bazar – especially the camaraderie between Krishna and Ghatotkacha – it is hard to imagine these same people in that distant, calculated scenario on the Kurukshetra battlefield.

But the thing is, Maya Bazar exists in its own bubble or vacuum. It is unconcerned with what is to come in an uncertain future, it is rooted in a fantasy present where all the good guys will emerge unscathed after having had some fun with the bad guys. Viewed in isolation, it plays a bit like a moralistic but comical and (mostly) non-violent version of the Mahabharata. The Pandavas never even appear in this three-hour film; Draupadi only appears in one fleeting moment early on, which provides a signpost for the depth of the Kauravas’ evil.

As Vamsee Juluri put it in his book Bollywood Nation: India Through its Cinema, “Some of the most popular [Telugu] mythological films of this time focus not on a pedagogic panorama of well-known episodes, but instead on minor, seemingly unimportant tales […] they are less about the whims and fancies of the Gods, and more about what happens when they are enmeshed in the web of human relationships.”

In critical renderings of the Mahabharata – the ones that are concerned with the big picture – Ghatotkacha and Abhimanyu occupy very different positions when it comes to the question of legitimacy. Despite Ghatotkacha being the oldest child of a Pandava, and the many references to their affection for him, it is clear that he is not an official heir; he exists on the margins of their kingdom. (“I live in another world, and I must go back with my mother,” he tells his father Bheema in a poignant scene in Peter Brook’s film version of the epic, “But if one day you need me, I’ll hear your call.”) Yet the effect of folk-takes like Sasirekha Parinayam – and other similar variations on the main Mahabharata story – is to reclaim this “rakshasa” prince as a member of the inner circle.

One of the themes of Maya Bazar is that appearances can be deceptive and that identity can be fluid (a princess celebrating her upcoming wedding through a song might make un-ladylike expressions and “manspreading” gestures) – and we are prepared for this theme by that opening scene, which briefly places Abhimanyu and Ghatotkacha in opposition, then unites them. Here they are, one the legitimate Pandava heir, the other an outsider who (in conventional Mahabharata tellings) is treated as a distant ally summoned to make a sacrifice; and yet here is a moment where they are enjoined together in genuine kinship, all boundaries falling away. It is one of the loveliest conceits of this film about a marketplace of illusions where anything can happen.

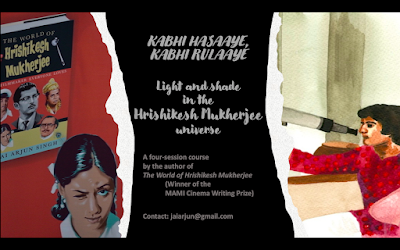

January 6, 2021

"I'm naatak-ing!" A course about Hrishikesh Mukherjee's cinema

Here are the details of the online course I will be teaching about Hrishikesh Mukherjee's cinema, starting January 24. Anyone who would like to sign up, please mail me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) -- and please spread the word to others who might be interested.

Here are the details of the online course I will be teaching about Hrishikesh Mukherjee's cinema, starting January 24. Anyone who would like to sign up, please mail me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) -- and please spread the word to others who might be interested.Starting in the late 1950s – when he went from being an editor and assistant director to making his own films – Hrishikesh Mukherjee became the best-known practitioner of the Middle Cinema, a term for gentle, grounded Hindi films that occupied a niche between the larger-than-life mainstream movie and the self-consciously realistic or minimalist “art film”. Working in this middle space for four decades, Hrishi-da, as he was popularly known, helmed dozens of films including such all-time favourites as Anand, Gol Maal, Guddi, Chupke Chupke, Anari, Bawarchi, Abhimaan, and Anupama. His best work struck a fine balance between fun and solemnity, using soufflé-like narratives to express thoughtful ideas about people, how they relate to each other and the world around them, and about the vital link between fantasy and life.

This four-session course will look at some of Hrishi-da’s most beloved films as well as some of his neglected gems. Talking points will include his use of music, recurrent themes such as role-playing and masquerade, the inspirations behind some of his best-known work, and how he managed to practice a form of personal, intimate cinema even as he consistently worked with the industry’s biggest stars. We will look at and discuss specific clips during these sessions, and also talk about some of the criticisms that have been leveled at him by those who were dissatisfied with either the form or content of his films.

It will be useful for participants to have a degree of familiarity with a few of Hrishi-da’s films, but it isn’t imperative. In any case, while keeping the focus on his work, we will also be talking more generally about different filmmaking styles and approaches, of which the Middle Cinema is one.

While the main course will be spread over four sessions, in the fifth week there will be a bonus session for extended, informal discussion as well as some music.

Dates and timings

Five Sundays: January 24, January 31, February 7, February 14, February 21

7.30 pm to 9 pm IST

A few of those who have mailed me expressing interest are in time zones that make the above hours impractical. Accordingly, I am offering an additional option for each of the four main classes, on the same dates:

10 am to 11.30 am IST

If you mail me confirming your interest in this module, please also mention your preferred time. If a reasonable number of participants apply for the morning slot, I will conduct each of these sessions across both timings.

(Recordings of each session will be sent to all the participants.)

Fees for the course

For participants in India and Asia:

Rs 4000

For participants outside Asia:

$125

(For any other information, please mail: jaiarjun@gmail.com)

December 25, 2020

Film discussion: Olivia de Havilland, The Heiress, The Snake Pit

"I can be very cruel. I have been taught by masters.”For the next online film-club discussion, a little tribute to Olivia de Havilland (who died earlier this year aged 104) — and also a continuation of the “Henry James on film” theme. The film is The Heiress (1949), for which de Havilland received her second best actress Oscar. Based on James’s novel Washington Square and set in the 1850s, this is the story of a shy young woman caught between her cold-hearted father and a charming suitor who might be a gold-digger. To me, this is an exemplar of the conversation-driven film that appears mannered and restrained and generally old-world-ish, but has a strong electric charge running beneath the surface. (As its director William Wyler said, “The emotion and conflict between two people in a drawing room can be more exciting than a gun battle.”) With a wonderful supporting cast including Ralph Richardson, the young Montgomery Clift (one of the first major “Method” actors in American film), and Miriam Hopkins (a magnificently impish performer who had lit the screen up in many 1930s films) as the protagonist’s aunt.

"I can be very cruel. I have been taught by masters.”For the next online film-club discussion, a little tribute to Olivia de Havilland (who died earlier this year aged 104) — and also a continuation of the “Henry James on film” theme. The film is The Heiress (1949), for which de Havilland received her second best actress Oscar. Based on James’s novel Washington Square and set in the 1850s, this is the story of a shy young woman caught between her cold-hearted father and a charming suitor who might be a gold-digger. To me, this is an exemplar of the conversation-driven film that appears mannered and restrained and generally old-world-ish, but has a strong electric charge running beneath the surface. (As its director William Wyler said, “The emotion and conflict between two people in a drawing room can be more exciting than a gun battle.”) With a wonderful supporting cast including Ralph Richardson, the young Montgomery Clift (one of the first major “Method” actors in American film), and Miriam Hopkins (a magnificently impish performer who had lit the screen up in many 1930s films) as the protagonist’s aunt.  I also have a very good print of the 1948 film The Snake Pit, which was one of de Havilland's most acclaimed performances -- she plays a woman who has been committed to a lunatic asylum (as such places were politely called in the old days), with large gaps in her memory and sense of what has been going on in her life. Anyone interested in these films and/or the discussion, mail me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) and I’ll share the prints.

I also have a very good print of the 1948 film The Snake Pit, which was one of de Havilland's most acclaimed performances -- she plays a woman who has been committed to a lunatic asylum (as such places were politely called in the old days), with large gaps in her memory and sense of what has been going on in her life. Anyone interested in these films and/or the discussion, mail me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) and I’ll share the prints. December 21, 2020

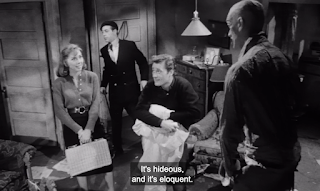

Key scenes from a movie nerd's life: Jonathan Brewster comes home in Arsenic and Old Lace

The first image here – the two shadowy figures entering a darkened room – is from a scene, and a film, that is very special to me; I watched it many times as a 13/14-year-old, having somehow procured a VHS cassette, and whenever this sequence began I felt the thrill that comes with knowing that a dark (but basically cosy and reassuring) comedy is about to move into slightly edgier terrain. That new twists and revelations lie ahead. This is the moment when two outstanding character actors make their first appearance in the 1944 Arsenic and Old Lace: Raymond Massey as Jonathan Brewster, an escaped convict returning to his family house (and displeased that inept plastic surgery has made his face resemble the Frankenstein Monster’s); and Peter Lorre as the scared little Doctor Einstein, the one who bungled the surgery.

The first image here – the two shadowy figures entering a darkened room – is from a scene, and a film, that is very special to me; I watched it many times as a 13/14-year-old, having somehow procured a VHS cassette, and whenever this sequence began I felt the thrill that comes with knowing that a dark (but basically cosy and reassuring) comedy is about to move into slightly edgier terrain. That new twists and revelations lie ahead. This is the moment when two outstanding character actors make their first appearance in the 1944 Arsenic and Old Lace: Raymond Massey as Jonathan Brewster, an escaped convict returning to his family house (and displeased that inept plastic surgery has made his face resemble the Frankenstein Monster’s); and Peter Lorre as the scared little Doctor Einstein, the one who bungled the surgery.

What these two practitioners of crime don’t realise is that some very strange (and unlawful, to say the least) things have been happening in the house where they are seeking sanctuary from the law. Their two sweet old aunts have been (this is not a spoiler) poisoning elderly gentlemen – with the best of intentions, of course. Meanwhile one of the other nephews thinks he is Teddy Roosevelt and has happily helped the old dears to bury the bodies in the cellar, believing them to be Yellow Fever victims. And yet another nephew Mortimer (played by Cary Grant) has only just discovered these subterranean secrets – on the very day that he is supposed to be heading off for his honeymoon.

What these two practitioners of crime don’t realise is that some very strange (and unlawful, to say the least) things have been happening in the house where they are seeking sanctuary from the law. Their two sweet old aunts have been (this is not a spoiler) poisoning elderly gentlemen – with the best of intentions, of course. Meanwhile one of the other nephews thinks he is Teddy Roosevelt and has happily helped the old dears to bury the bodies in the cellar, believing them to be Yellow Fever victims. And yet another nephew Mortimer (played by Cary Grant) has only just discovered these subterranean secrets – on the very day that he is supposed to be heading off for his honeymoon.  This is a stagy film in some ways – being a very faithful adaptation of a popular play – but a lot of fun if you get into the mood. It also has one of Cary Grant's most deliriously over-the-top comic performances – one that I love, though it will definitely not be to all tastes. Watching this film now, I wonder if Grant was on some of the LSD that he later supposedly introduced Tim Leary to. I have a print with me now, so if anyone wants to watch it, mail me at jaiarjun@gmail.com. (I don’t think I will be having a film-club conversation around it, but maybe as part of something on black comedies soon.)

This is a stagy film in some ways – being a very faithful adaptation of a popular play – but a lot of fun if you get into the mood. It also has one of Cary Grant's most deliriously over-the-top comic performances – one that I love, though it will definitely not be to all tastes. Watching this film now, I wonder if Grant was on some of the LSD that he later supposedly introduced Tim Leary to. I have a print with me now, so if anyone wants to watch it, mail me at jaiarjun@gmail.com. (I don’t think I will be having a film-club conversation around it, but maybe as part of something on black comedies soon.)

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers