Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 77

June 20, 2013

On the appeal of pre-historic special effects

(Continuing thoughts from the Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde transformation scenes mentioned in the last post)

The discussion about whether movies are “better” or “worse” today vis-a-vis an earlier time is a pointless and irresolvable one, subject to shifting benchmarks, individual tastes and hard-line biases that run both ways, from the Golden Ageist syndrome (the past was always a better place than the present / old songs were so melodious, today it’s all noise) to contemporary chauvinism (old movies are awkward and creaky / black-and-white is boring). But one area where something resembling consensus is possible is when assessing technological improvements. Though I haven’t seen the new Superman film yet, I have no trouble accepting that it is probably much more visually fluid – and a grander aesthetic experience – than the 1978 Superman; and this despite the fact that I have irrationally defensive feelings about the latter, having grown up with it.

However, agreeing that technology is objectively superior today – and that more things are now possible in movie-making, things that would have been regarded as magic a hundred years ago – is not the same as saying that modern CGI is always more effective than techniques used in the distant past. As I have written before about films like Fritz Lang’s Siegfried or the original King Kong, the use of a papier-mâché dragon or stop-motion animation can give a fantasy or horror film a primal, viscerally stirring quality, because it feels otherworldly and removed from our regular experience – whereas modern computer effects by their very nature make everything crystal-clear and even commonplace, so that the image of a giant monkey fighting a giant dinosaur, or a Balrog battling Gandalf on a narrow bridge, becomes as credible as a weekend outing to the local mall (assuming of course that you think of malls and their zombie patrons as real-world things).

However, agreeing that technology is objectively superior today – and that more things are now possible in movie-making, things that would have been regarded as magic a hundred years ago – is not the same as saying that modern CGI is always more effective than techniques used in the distant past. As I have written before about films like Fritz Lang’s Siegfried or the original King Kong, the use of a papier-mâché dragon or stop-motion animation can give a fantasy or horror film a primal, viscerally stirring quality, because it feels otherworldly and removed from our regular experience – whereas modern computer effects by their very nature make everything crystal-clear and even commonplace, so that the image of a giant monkey fighting a giant dinosaur, or a Balrog battling Gandalf on a narrow bridge, becomes as credible as a weekend outing to the local mall (assuming of course that you think of malls and their zombie patrons as real-world things).

Personally I feel a thrill every time I see “special effects” in a very old film because one gets a firsthand sense of human minds working with a young medium, trying to supersede the limitedness of available resources. Almost since its inception, cinema has adapted literary works that contain supernatural elements – see this 1903 version of Alice in Wonderland – and some of the early filmmakers seem like masochists setting themselves impossible tasks rather than simply using the motion-picture camera to record everyday things (which would have been a worthy enough pursuit, given how new the technology was). Today, with an adequate scale of production, it is possible to create a convincing visual representation of just about any story, no matter how outlandish the setting. But 110 years ago, just figuring out how to show the disembodied head of the Cheshire Cat in such a way that it looked like a halfway-alive thing (as opposed to a cardboard cut-out pasted on the set) would have required intense brainstorming.

pursuit, given how new the technology was). Today, with an adequate scale of production, it is possible to create a convincing visual representation of just about any story, no matter how outlandish the setting. But 110 years ago, just figuring out how to show the disembodied head of the Cheshire Cat in such a way that it looked like a halfway-alive thing (as opposed to a cardboard cut-out pasted on the set) would have required intense brainstorming.

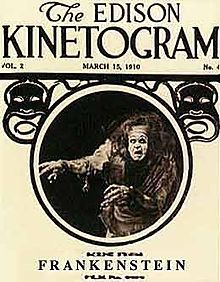

In 1910, Thomas Edison’s studio made a 12-minute-long version of Frankenstein, which is extant today and can be found on YouTube. The film is as jerky and theatrical to modern eyes as you might expect, but there is genuine inventiveness in a couple of scenes, including one with a large mirror in which the Monster eventually disappears (raising the question of whether he was a figment of his creator’s imagination or perhaps an alter ego). For the difficult scene in which Frankenstein’s unworldly creation comes alive, the filmmakers put a life-size wax replica of a skeleton in a big vat and set fire to it so that it slowly dissolved and crumpled (meanwhile someone out of sight moved its arms around a bit). They then played the film backwards, so that one gets the impression of something hideous being forged out of fire until it sits upright, a ghastly mockery of the human form.

Much of the pleasure of watching this scene comes not from its visual appeal (though if you’re in the right mood, it does have a creepy appeal) but from imagining the problem-solving process: the discussions that these pioneers of film must have engaged in decades before the advent of computer technology (or anything else that we would think of as “special effects” today), the other things they might have tried and failed miserably at, the possibility that they needed to build multiple wax figures and experiment with the intensity of the fire because the first few attempts didn’t work. How random and slapdash it seems to us today, yet how vital it was to the writing of movie grammar, and to the creative growth of a medium that was often dismissed at the time as having no artistic future because it was simply a bland reproduction of reality.

Much of the pleasure of watching this scene comes not from its visual appeal (though if you’re in the right mood, it does have a creepy appeal) but from imagining the problem-solving process: the discussions that these pioneers of film must have engaged in decades before the advent of computer technology (or anything else that we would think of as “special effects” today), the other things they might have tried and failed miserably at, the possibility that they needed to build multiple wax figures and experiment with the intensity of the fire because the first few attempts didn’t work. How random and slapdash it seems to us today, yet how vital it was to the writing of movie grammar, and to the creative growth of a medium that was often dismissed at the time as having no artistic future because it was simply a bland reproduction of reality.

[Did a version of this for my Business Standard film column]

The discussion about whether movies are “better” or “worse” today vis-a-vis an earlier time is a pointless and irresolvable one, subject to shifting benchmarks, individual tastes and hard-line biases that run both ways, from the Golden Ageist syndrome (the past was always a better place than the present / old songs were so melodious, today it’s all noise) to contemporary chauvinism (old movies are awkward and creaky / black-and-white is boring). But one area where something resembling consensus is possible is when assessing technological improvements. Though I haven’t seen the new Superman film yet, I have no trouble accepting that it is probably much more visually fluid – and a grander aesthetic experience – than the 1978 Superman; and this despite the fact that I have irrationally defensive feelings about the latter, having grown up with it.

However, agreeing that technology is objectively superior today – and that more things are now possible in movie-making, things that would have been regarded as magic a hundred years ago – is not the same as saying that modern CGI is always more effective than techniques used in the distant past. As I have written before about films like Fritz Lang’s Siegfried or the original King Kong, the use of a papier-mâché dragon or stop-motion animation can give a fantasy or horror film a primal, viscerally stirring quality, because it feels otherworldly and removed from our regular experience – whereas modern computer effects by their very nature make everything crystal-clear and even commonplace, so that the image of a giant monkey fighting a giant dinosaur, or a Balrog battling Gandalf on a narrow bridge, becomes as credible as a weekend outing to the local mall (assuming of course that you think of malls and their zombie patrons as real-world things).

However, agreeing that technology is objectively superior today – and that more things are now possible in movie-making, things that would have been regarded as magic a hundred years ago – is not the same as saying that modern CGI is always more effective than techniques used in the distant past. As I have written before about films like Fritz Lang’s Siegfried or the original King Kong, the use of a papier-mâché dragon or stop-motion animation can give a fantasy or horror film a primal, viscerally stirring quality, because it feels otherworldly and removed from our regular experience – whereas modern computer effects by their very nature make everything crystal-clear and even commonplace, so that the image of a giant monkey fighting a giant dinosaur, or a Balrog battling Gandalf on a narrow bridge, becomes as credible as a weekend outing to the local mall (assuming of course that you think of malls and their zombie patrons as real-world things).Personally I feel a thrill every time I see “special effects” in a very old film because one gets a firsthand sense of human minds working with a young medium, trying to supersede the limitedness of available resources. Almost since its inception, cinema has adapted literary works that contain supernatural elements – see this 1903 version of Alice in Wonderland – and some of the early filmmakers seem like masochists setting themselves impossible tasks rather than simply using the motion-picture camera to record everyday things (which would have been a worthy enough

pursuit, given how new the technology was). Today, with an adequate scale of production, it is possible to create a convincing visual representation of just about any story, no matter how outlandish the setting. But 110 years ago, just figuring out how to show the disembodied head of the Cheshire Cat in such a way that it looked like a halfway-alive thing (as opposed to a cardboard cut-out pasted on the set) would have required intense brainstorming.

pursuit, given how new the technology was). Today, with an adequate scale of production, it is possible to create a convincing visual representation of just about any story, no matter how outlandish the setting. But 110 years ago, just figuring out how to show the disembodied head of the Cheshire Cat in such a way that it looked like a halfway-alive thing (as opposed to a cardboard cut-out pasted on the set) would have required intense brainstorming.In 1910, Thomas Edison’s studio made a 12-minute-long version of Frankenstein, which is extant today and can be found on YouTube. The film is as jerky and theatrical to modern eyes as you might expect, but there is genuine inventiveness in a couple of scenes, including one with a large mirror in which the Monster eventually disappears (raising the question of whether he was a figment of his creator’s imagination or perhaps an alter ego). For the difficult scene in which Frankenstein’s unworldly creation comes alive, the filmmakers put a life-size wax replica of a skeleton in a big vat and set fire to it so that it slowly dissolved and crumpled (meanwhile someone out of sight moved its arms around a bit). They then played the film backwards, so that one gets the impression of something hideous being forged out of fire until it sits upright, a ghastly mockery of the human form.

Much of the pleasure of watching this scene comes not from its visual appeal (though if you’re in the right mood, it does have a creepy appeal) but from imagining the problem-solving process: the discussions that these pioneers of film must have engaged in decades before the advent of computer technology (or anything else that we would think of as “special effects” today), the other things they might have tried and failed miserably at, the possibility that they needed to build multiple wax figures and experiment with the intensity of the fire because the first few attempts didn’t work. How random and slapdash it seems to us today, yet how vital it was to the writing of movie grammar, and to the creative growth of a medium that was often dismissed at the time as having no artistic future because it was simply a bland reproduction of reality.

Much of the pleasure of watching this scene comes not from its visual appeal (though if you’re in the right mood, it does have a creepy appeal) but from imagining the problem-solving process: the discussions that these pioneers of film must have engaged in decades before the advent of computer technology (or anything else that we would think of as “special effects” today), the other things they might have tried and failed miserably at, the possibility that they needed to build multiple wax figures and experiment with the intensity of the fire because the first few attempts didn’t work. How random and slapdash it seems to us today, yet how vital it was to the writing of movie grammar, and to the creative growth of a medium that was often dismissed at the time as having no artistic future because it was simply a bland reproduction of reality.[Did a version of this for my Business Standard film column]

Published on June 20, 2013 20:32

June 18, 2013

Elbow on knee, heart in film - Rouben Mamoulian on the natural and the true

In my short list of “books to keep on a desert island”, one place is permanently reserved for the anthology

Conversations with the Great Movie-Makers of Hollywood’s Golden Age

. As a reader this book is always a work in progress for me, a living, shifting thing: I might set it aside for months on end, then dip into it again for just a few minutes and emerge with a new treasure. Even the familiar passages are worth revisiting over time because the filmmakers’ insights – and the diversity and occasional contradictions in their views – become more meaningful as you watch more of their films. (If that desert island didn’t have a DVD player and an electricity connection, this book would lose much of its appeal.)

There are dozens of quotes I’d like to share from Conversations, but for now here is something by Rouben Mamoulian, who made one of my favourite movies, the 1931 version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde . This is Mamoulian, speaking at a seminar, on stylization, realism and what literary critics sometimes refer to as “poetic truth” (as opposed to literal truth).

As you'd expect then, Mamoulian’s version of the Jekyll-Hyde story is a brilliantly stylized work, and one of the most impressive-looking movies of its time. The first two or three years of the sound era were a generally poor time for visual inventiveness, because movie-makers already had so much on their hands dealing with problems caused by primitive recording technology. (Remember this scene in Singin’ in the Rain?) But Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a testament to what Mamoulian says elsewhere in the seminar: “My interest in the camera was always in the marvellous things you can do with it – with the angles, the dollying, the dissolves, the props, and the framing”. The film was also remarkably imaginative when it came to special effects, as in the famous transformation scenes where Fredric March’s Jekyll slowly, painfully becomes the simian-like Hyde.

Below are two videos of these scenes. The first one has a couple of cleverly disguised cuts as the camera moves from Jekyll’s face to his hands and back again, but the first 25 seconds provide an unbroken view of his face appearing to darken and change.

This must have been astonishing for audiences of the time, and the secret of the transformation was revealed only years later: different layers of coloured makeup had been applied on March’s face, and matching light filters were used at the beginning so that the makeup wasn’t visible on black-and-white film; as the scene progressed, the filters were changed and the makeup came into view, “magically” casting shadows on the actor’s face. It's a great example of problem-solving in an era when the computer effects of today were barely imaginable.

This second video has another transformation scene (beginning around the 55-second mark with the camera adopting Jekyll’s POV as he looks into a mirror). Here again, you can see March’s face changing colour, but the rest of the scene is equally notable for its use of the disorienting, rotating camera and a proto-psychedelic soundtrack that anticipates what Pink Floyd and others would be doing in underground clubs 35 years later.

But I’ll give the last word to Mamoulian again – here he is on the use of sound for this scene:

There are dozens of quotes I’d like to share from Conversations, but for now here is something by Rouben Mamoulian, who made one of my favourite movies, the 1931 version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde . This is Mamoulian, speaking at a seminar, on stylization, realism and what literary critics sometimes refer to as “poetic truth” (as opposed to literal truth).

I’ve always believed in stylization and poetry. Even on the stage, things are stylized – every movement, every grouping. If you preserve the psychological truth of the emotions and thoughts of the actors, and combine that with physical expression that is utterly stylized and that couldn’t happen in real life, the impact upon the audience is one of greater reality. Perhaps that’s why they call it surrealism [...] Done correctly, stylization carries greater reality in its impact on the audience than everyday kitchen-sink naturalism can ever achieve.

[...] Stylization is really an extension of feeling and thought, a sharper way of showing that thought. Let me all ask you a question. You probably know “The Thinker”, the great statue of Auguste Rodin. Will you show me how he sits? Let’s see.Without exception all of you are wrong. It never fails. His man is sitting, believe it or not, with one elbow on the opposite knee. It’s not natural or comfortable, but aesthetically and artistically it has a focus. It has design and rhythm and power. So, what is unnatural becomes true, and you can apply this idea to any kind of a scene. You can put everything upside down or reverse it, provided what it does is sharpen. In your desire to express love or hate or doubt, whatever it is, you ask yourself “How can I express this more acutely?” Then you’ll wind up with a gesture that is not natural, but perfect as an expression of that thought.

As you'd expect then, Mamoulian’s version of the Jekyll-Hyde story is a brilliantly stylized work, and one of the most impressive-looking movies of its time. The first two or three years of the sound era were a generally poor time for visual inventiveness, because movie-makers already had so much on their hands dealing with problems caused by primitive recording technology. (Remember this scene in Singin’ in the Rain?) But Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a testament to what Mamoulian says elsewhere in the seminar: “My interest in the camera was always in the marvellous things you can do with it – with the angles, the dollying, the dissolves, the props, and the framing”. The film was also remarkably imaginative when it came to special effects, as in the famous transformation scenes where Fredric March’s Jekyll slowly, painfully becomes the simian-like Hyde.

Below are two videos of these scenes. The first one has a couple of cleverly disguised cuts as the camera moves from Jekyll’s face to his hands and back again, but the first 25 seconds provide an unbroken view of his face appearing to darken and change.

This must have been astonishing for audiences of the time, and the secret of the transformation was revealed only years later: different layers of coloured makeup had been applied on March’s face, and matching light filters were used at the beginning so that the makeup wasn’t visible on black-and-white film; as the scene progressed, the filters were changed and the makeup came into view, “magically” casting shadows on the actor’s face. It's a great example of problem-solving in an era when the computer effects of today were barely imaginable.

This second video has another transformation scene (beginning around the 55-second mark with the camera adopting Jekyll’s POV as he looks into a mirror). Here again, you can see March’s face changing colour, but the rest of the scene is equally notable for its use of the disorienting, rotating camera and a proto-psychedelic soundtrack that anticipates what Pink Floyd and others would be doing in underground clubs 35 years later.

But I’ll give the last word to Mamoulian again – here he is on the use of sound for this scene:

I asked, “What kind of sound can we put with this? The whole thing is fantastic. You put a realistic sound and it will get you nowhere at all.” So again, you proceed from imagination and theory and if it makes sense, do it. I said, “We’re not going to have a single sound in this transformation that you can hear in life.” They said, “What are you going to use?” I said, “We’ll light the candle and photograph the light – high frequencies, low frequencies, direct from light into sound. Then we’ll hit a gong, cut off the impact, run it backward, things like that.” So I had this terrific kind of stew, a mélange of sounds that do not exist in nature or in life. It was eerie but it lacked a beat, and that’s where I had to introduce rhythm. We tried all sorts of drums, but they all sounded like drums. When you run all out of ideas, something always pops into your head. I said, “I’ve got it.” I ran up and down the stairway for two minutes until my heart was really pounding, took the microphone down and said, “Record me.” And that’s the rhythm of the big transformation. So when I say my heart was in Jekyll and Hyde, it’s literally true.

Published on June 18, 2013 01:22

June 12, 2013

On Habib Tanvir, Shyam Benegal, and a truthful thief

Given that Shyam Benegal is one of our most respected directors, I’m a little surprised by the under-the-radar status of his second feature film, the 1975 Charandas Chor . This version of Habib Tanvir’s famous play about an honest thief was done in collaboration with Tanvir – before the play itself had acquired its final shape – and I think it is one of Benegal's most enjoyable movies and one of Hindi cinema’s sharpest satires. But it is often overlooked, perhaps because it was made for the Children's Film Society and therefore seen as being geared to a non-adult audience. I have read Benegal profiles that refer to Ankur, Nishant and Manthan – cornerstones of the Indian New Wave – as his first three films, with no mention of Charandas Chor. (See the second sentence of this Wikipedia entry, for starters, and the “Feature Films” subhead.) Even Dibakar Banerjee – a voracious movie-watcher and a big Benegal fan – had not seen the film when I spoke with him last year, though he was certainly familiar with Tanvir’s play. (Banerjee noted that the play contained a precedent for the Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! theme of a thief’s career becoming a comment on the society around him.)

The neglect notwithstanding, Charandas Chor is a notable film on many levels. It represents a rare meeting between cinema and folk theatre (with vital contributions by musicians and actors of the Chhatisgarhi Nacha troupes who worked with Tanvir) and is a document of one of our most significant modern plays in a nascent, transitional form – but it is also recognisably a film, cinematically imaginative and dynamic. It was one of Govind Nihalani’s most impressive early outings as a cinematographer, as well as the feature debut of the young Smita Patil, as a beautiful princess who is besotted by the bumpkin Charandas.

Despite the seriousness of its themes, its form is that of a playful entertainment from the very first image, a medium shot of a doleful-looking donkey, its tail apparently wagging in tune to the folk-song on the soundtrack. While this animal plays a functional part in the narrative (it belongs to a dhobi who will become Charandas Chor’s sidekick), the ass motif is integral in a wider sense: many of the side-characters, including a “chatur vakeel” (clever lawyer), are depicted in illustrations as donkeys that Charandas will get the better of (or expose as hypocrites). The film's episodic structure is quickly established too, with Charandas (Lalu Ram) encountering the dhobi Buddhu (Madan Lal), who wishes to become his chela. The scene employs the language of an enlightened guru addressing his disciples: asked to impart his gyaan of thievery, Charandas replies, "यह कला है, बेटा - बड़ी साधना से मिलती है।" (“This is an art, son – it requires practice and rigour.”)

Despite the seriousness of its themes, its form is that of a playful entertainment from the very first image, a medium shot of a doleful-looking donkey, its tail apparently wagging in tune to the folk-song on the soundtrack. While this animal plays a functional part in the narrative (it belongs to a dhobi who will become Charandas Chor’s sidekick), the ass motif is integral in a wider sense: many of the side-characters, including a “chatur vakeel” (clever lawyer), are depicted in illustrations as donkeys that Charandas will get the better of (or expose as hypocrites). The film's episodic structure is quickly established too, with Charandas (Lalu Ram) encountering the dhobi Buddhu (Madan Lal), who wishes to become his chela. The scene employs the language of an enlightened guru addressing his disciples: asked to impart his gyaan of thievery, Charandas replies, "यह कला है, बेटा - बड़ी साधना से मिलती है।" (“This is an art, son – it requires practice and rigour.”) But this being a parable about the duplicities of social structures – including the ones rooted in class and religion – we also meet a “real” guru who, as Charandas observes, has an even more efficient money-making gig going. “आपका धंदा बैठे बैठे, और आमदनी ज़्यादा" (“You sit and do nothing, but earn more than me”) he tells the sadhu with genuine reverence in his eyes. This lampooning of authority figures extends across hierarchies: for instance, a view of temple idols shorn of their ornaments (making them look bald, comical and most un-Godly) is echoed by a shot of three unclothed policemen drying their uniforms by the riverbank. Through most of these episodes, the chor maintains his essential dignity and his moral compass while the “law-abiding” world is revealed as hollow, rotting or plain naked.

But this being a parable about the duplicities of social structures – including the ones rooted in class and religion – we also meet a “real” guru who, as Charandas observes, has an even more efficient money-making gig going. “आपका धंदा बैठे बैठे, और आमदनी ज़्यादा" (“You sit and do nothing, but earn more than me”) he tells the sadhu with genuine reverence in his eyes. This lampooning of authority figures extends across hierarchies: for instance, a view of temple idols shorn of their ornaments (making them look bald, comical and most un-Godly) is echoed by a shot of three unclothed policemen drying their uniforms by the riverbank. Through most of these episodes, the chor maintains his essential dignity and his moral compass while the “law-abiding” world is revealed as hollow, rotting or plain naked.There is so much to enjoy here, for children and adults alike. There is Nihalani’s black-and-white photography (inferior Orwo film had to be used due to import constraints of the time, but the occasional graininess goes well with the subject matter and the bucolic setting) and his imaginative use of zooms, particularly effective in chase

sequences that evoke the silent cinema's Keystone Kops. Also the Nacha music, which continually comments on the action, and wonderful lead performances by village actors from Tanvir’s Naya Theatre, including the emaciated Madan Lal – one of Tanvir’s favourite actors – who played Charandas on stage but plays Buddhu in the film.

sequences that evoke the silent cinema's Keystone Kops. Also the Nacha music, which continually comments on the action, and wonderful lead performances by village actors from Tanvir’s Naya Theatre, including the emaciated Madan Lal – one of Tanvir’s favourite actors – who played Charandas on stage but plays Buddhu in the film.Inter-titles are used like chapter heads, and Tanvir himself reads them out in his nasal voice, fumbling over big words the way a child might. ("बुद्धू का चोरी के दाव... दावपेंच सीखना।") In a funny little cameo, he also appears as an absent-minded judge who might have dropped in from Alice in Wonderland, holding large scissors and a walking stick instead of a

gavel***. And there is the casual drollness of such exchanges as the one where Charandas, miffed by the princess’s show of largesse, proudly tells her “मैं चोरी करता हूँ, दान नहीं लेता" (“I steal, I don’t accept alms”) while the sadhu standing behind her pipes up "दान लेना तो मेरा काम है, बेटी" ("Taking alms is what I do").

gavel***. And there is the casual drollness of such exchanges as the one where Charandas, miffed by the princess’s show of largesse, proudly tells her “मैं चोरी करता हूँ, दान नहीं लेता" (“I steal, I don’t accept alms”) while the sadhu standing behind her pipes up "दान लेना तो मेरा काम है, बेटी" ("Taking alms is what I do").*****

A few months ago I briefly spoke with Benegal about Charandas Chor, particularly the divergence between his version and the one that Tanvir finalised for the stage. One important difference was the ending: in both film and play Charandas is put to death, but in the film a humorous epilogue shows him plying his roguery in the afterlife, where he steals Yamraj’s buffalo and presumably sets off on a fresh round of adventures. (This narrative circularity is of course common to many myths or fables; one might also recall the last scene of Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, with the rake coolly strolling into the far distance as a TV news reporter blathers on.) But Tanvir’s later modifications to the play made it bleaker and more hard-hitting, with a conclusion that allowed his hero to maintain his integrity – to die for the truth he holds so dear, while the world around him continues on its merry path. “He turned it into a sophisticated tragedy,” Benegal told me, “whereas my film was a moral story done as a comedy for children.” The playwright also opted for a sparer, more minimalist idiom, removing the part of Buddhu along with other extraneous elements, including that zany courtroom scene.

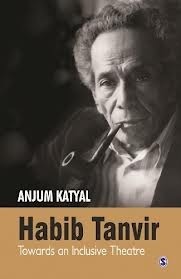

But film and play have one important thing in common: Tanvir and Benegal were both influenced by Brechtian alienation, wherein the audience is asked to be intellectually aware of the issues raised in a story, rather than becoming emotionally immersed in it or “forgetting” the constructed nature of what they are watching. In her book

Habib Tanvir: Towards an Inclusive Theatre

, Anjum Katyal observes that Tanvir made atypical use of Indian folk music: while our folk theatre tends to use songs in a didactic way (explicitly telling the audience what is good or bad), Charandas Chor follows the Brechtian technique of having two songs express contradictory ideas (e.g. one might say “Charandas is not really a thief, he is a good man, there are bigger thieves in society” while another goes “he is a dangerous thief, protect yourself from him”) and letting the viewer weigh each stance and consciously work out his own attitudes.

But film and play have one important thing in common: Tanvir and Benegal were both influenced by Brechtian alienation, wherein the audience is asked to be intellectually aware of the issues raised in a story, rather than becoming emotionally immersed in it or “forgetting” the constructed nature of what they are watching. In her book

Habib Tanvir: Towards an Inclusive Theatre

, Anjum Katyal observes that Tanvir made atypical use of Indian folk music: while our folk theatre tends to use songs in a didactic way (explicitly telling the audience what is good or bad), Charandas Chor follows the Brechtian technique of having two songs express contradictory ideas (e.g. one might say “Charandas is not really a thief, he is a good man, there are bigger thieves in society” while another goes “he is a dangerous thief, protect yourself from him”) and letting the viewer weigh each stance and consciously work out his own attitudes.Many of Benegal’s later films, notably Arohan (which begins with Om Puri directly addressing the camera, speaking about the subject of the film and introducing the other actors) and Samar , would use similar distancing techniques. One sees it also in Nihalani’s directorial ventures such as Party or Aghaat, where self-conscious, expository dialogue takes the place of naturalistic conversation. The film of Charandas Chor doesn’t do this to the same degree (it was, after all, made for children and needed something resembling a conventional narrative flow) but it does draw attention to the storytelling process through its titles, illustrations and voiceovers. At one point the images on the screen even shake and rupture – as if there were an error in the projection – and Tanvir’s sharp voice asks “Kahin film poori toh nahin ho gayi?” In its own way, this entertaining “children’s movie” is very much a companion piece to the meta-films in the new art cinema of the 70s and 80s.

P.S. For anyone interested in Tanvir, the English version of his unfinished memoirs (translated by the multi-talented writer, historian and dastangoi Mahmood Farooqui) has just been published. I haven’t yet read it, though I intend to (it only covers Tanvir’s life up to the 1950s, I think). Anjum Katyal’s study of his life and career, mentioned above, is strongly recommended too.

P.P.S. A few months ago I discovered that Charandas Chor was on YouTube in a good print, and despite my reservations about watching movies on a computer screen I grabbed this available option. Unfortunately the YouTube video was removed a few weeks ago. But perhaps this indicates that a fresh print of the film will soon be made available on DVD. One can hope.

*** The stammering judge in Charandas Chor is probably an extension of the role Tanvir played in the 1948 IPTA comedy play Jadu ki Kursi, which also had Balraj Sahni in an acclaimed lead performance.

Published on June 12, 2013 21:51

June 7, 2013

The pros and cons of being a movie-star with very little ego

After watching the trailer for

Yamla Pagla Deewana 2

– the Deol family film, which releases this week – I headed YouTube-wards to watch the song sequence from which the film gets its name: “Main Jat Yamla Pagla Deewana” from the 1975 film Pratigya. As a friend, a fellow Dharmendra fan, noted during a recent conversation, this is one of the most exuberant Hindi-movie scenes ever. “All the director had to do was put a liquor bottle in paaji’s hand, give him a large open space to goof around in, along with a jeep and a few other props, and tell him to invent whatever dance moves - or things that resembled dance moves - he felt comfortable doing. And the result was magic.”

Perhaps it can also be seen as an outtake from Dharmendra’s superb, boisterous performance as Veeru in Sholay, made a few months earlier. But watching the song, I was also reminded that for most of his lengthy career, Dharmendra had a remarkably unselfconscious screen presence. In much of his best work (and some of his worst work, but we’ll come to that), you get the sense of a man surprisingly bereft of ego; there is little trace of the self-absorption that has always been a prime quality of our leading men.

Perhaps it can also be seen as an outtake from Dharmendra’s superb, boisterous performance as Veeru in Sholay, made a few months earlier. But watching the song, I was also reminded that for most of his lengthy career, Dharmendra had a remarkably unselfconscious screen presence. In much of his best work (and some of his worst work, but we’ll come to that), you get the sense of a man surprisingly bereft of ego; there is little trace of the self-absorption that has always been a prime quality of our leading men.

For decades, Hindi-movie heroes of all stripes have carefully nurtured their screen images. The personas might vary from Dev Anand’s upbeat urbaneness to Dilip Kumar’s studied bouts with tragedy, but most of them (even the ones we think of as “understated”) come with tics suggesting that the star-actor knows exactly what effect he is having on the audience, and is determined to milk it. Hence Raj Kapoor’s martyred smiles as his awara or Joker deals with life’s injustices, or Rajesh Khanna’s romantic head-bobbing, or the young Manoj Kumar’s painfully evident knowledge that his handsomeness was too much for any Eastman Color processor to bear, hence his face had to be in side-profile or covered by his hand.

Dharmendra had mannerisms too, of course, but one rarely feels that he had pre-conceptions about what he should be doing on screen – from the beginning of his career, he seemed willing to do almost anything he was asked, to subjugate himself to the film. And this willingness to be putty in someone else's hands is a double-edged sword for a movie star. Working under such men as Bimal Roy, Chetan Anand and Hrishikesh Mukherjee in the 1960s, it could mean small but powerful character parts in movies of integrity. In slight but inoffensive thrillers like Saazish, it might entail "fighting and climbing rope ladders in his chaddies" (as Memsaab Story puts it in this post). But in the context of the direction his career took in the bad, bad 1980s (the “kuttay-kameenay” years), it became lack of discernment in role choices, complete disregard for personal dignity and sleep-walking his way through assembly-line multi-starrers with endless variations on the izzat and badlaa themes.

In the mid-1980s, I remember Rishi Kapoor getting praise for his self-effacement in playing secondary roles in woman-centric films like Prem Rog and Tawaif. Dharmendra was in a similar mould two decades earlier, a solid foot-soldier to strong heroines such as Nutan, Meena Kumari and Sharmila Tagore in such films as Bandini, Majhli Didi, Anupama (or even a tiny but important cameo in the Waheeda Rehman-starrer Khamoshi). During this time, he was among our most likable romantic leads and even, depending on the film, something of a sex symbol. He then developed into a marvelous physical comedian and a convincing action hero (both qualities converging in the train-attack sequence in Sholay), but what worked so well in some of the early films soon made way for unthinking repetition. Well into his sixties, he continued doing C-grade action films made specifically for audiences outside the urban centres. (Just the other day, I saw him in this thing called Sultaan on TV, looking old and haggard but mechanically participating in badly choreographed fight scenes.)

It is a pity that such films may have marred the legacy of this underappreciated performer, but it is never too late for redemption. With the Yamla Pagla Deewana films containing many allusions to dialogues and scenes from his old movies, there are signs that Dharmendra may belatedly have developed a sense of self-importance, a meta-sense of his own filmic past. The man who so bashfully played "himself" in Guddi – as a star who is, aw-shucks, just a regular guy – may now, at age 78, be facing up to his legacy. And regardless of the quality of the YPD ego-projects, it is a legacy that deserves to be rediscovered.

[An earlier post on Dharmendra here]

Perhaps it can also be seen as an outtake from Dharmendra’s superb, boisterous performance as Veeru in Sholay, made a few months earlier. But watching the song, I was also reminded that for most of his lengthy career, Dharmendra had a remarkably unselfconscious screen presence. In much of his best work (and some of his worst work, but we’ll come to that), you get the sense of a man surprisingly bereft of ego; there is little trace of the self-absorption that has always been a prime quality of our leading men.

Perhaps it can also be seen as an outtake from Dharmendra’s superb, boisterous performance as Veeru in Sholay, made a few months earlier. But watching the song, I was also reminded that for most of his lengthy career, Dharmendra had a remarkably unselfconscious screen presence. In much of his best work (and some of his worst work, but we’ll come to that), you get the sense of a man surprisingly bereft of ego; there is little trace of the self-absorption that has always been a prime quality of our leading men.For decades, Hindi-movie heroes of all stripes have carefully nurtured their screen images. The personas might vary from Dev Anand’s upbeat urbaneness to Dilip Kumar’s studied bouts with tragedy, but most of them (even the ones we think of as “understated”) come with tics suggesting that the star-actor knows exactly what effect he is having on the audience, and is determined to milk it. Hence Raj Kapoor’s martyred smiles as his awara or Joker deals with life’s injustices, or Rajesh Khanna’s romantic head-bobbing, or the young Manoj Kumar’s painfully evident knowledge that his handsomeness was too much for any Eastman Color processor to bear, hence his face had to be in side-profile or covered by his hand.

Dharmendra had mannerisms too, of course, but one rarely feels that he had pre-conceptions about what he should be doing on screen – from the beginning of his career, he seemed willing to do almost anything he was asked, to subjugate himself to the film. And this willingness to be putty in someone else's hands is a double-edged sword for a movie star. Working under such men as Bimal Roy, Chetan Anand and Hrishikesh Mukherjee in the 1960s, it could mean small but powerful character parts in movies of integrity. In slight but inoffensive thrillers like Saazish, it might entail "fighting and climbing rope ladders in his chaddies" (as Memsaab Story puts it in this post). But in the context of the direction his career took in the bad, bad 1980s (the “kuttay-kameenay” years), it became lack of discernment in role choices, complete disregard for personal dignity and sleep-walking his way through assembly-line multi-starrers with endless variations on the izzat and badlaa themes.

In the mid-1980s, I remember Rishi Kapoor getting praise for his self-effacement in playing secondary roles in woman-centric films like Prem Rog and Tawaif. Dharmendra was in a similar mould two decades earlier, a solid foot-soldier to strong heroines such as Nutan, Meena Kumari and Sharmila Tagore in such films as Bandini, Majhli Didi, Anupama (or even a tiny but important cameo in the Waheeda Rehman-starrer Khamoshi). During this time, he was among our most likable romantic leads and even, depending on the film, something of a sex symbol. He then developed into a marvelous physical comedian and a convincing action hero (both qualities converging in the train-attack sequence in Sholay), but what worked so well in some of the early films soon made way for unthinking repetition. Well into his sixties, he continued doing C-grade action films made specifically for audiences outside the urban centres. (Just the other day, I saw him in this thing called Sultaan on TV, looking old and haggard but mechanically participating in badly choreographed fight scenes.)

It is a pity that such films may have marred the legacy of this underappreciated performer, but it is never too late for redemption. With the Yamla Pagla Deewana films containing many allusions to dialogues and scenes from his old movies, there are signs that Dharmendra may belatedly have developed a sense of self-importance, a meta-sense of his own filmic past. The man who so bashfully played "himself" in Guddi – as a star who is, aw-shucks, just a regular guy – may now, at age 78, be facing up to his legacy. And regardless of the quality of the YPD ego-projects, it is a legacy that deserves to be rediscovered.

[An earlier post on Dharmendra here]

Published on June 07, 2013 00:43

June 1, 2013

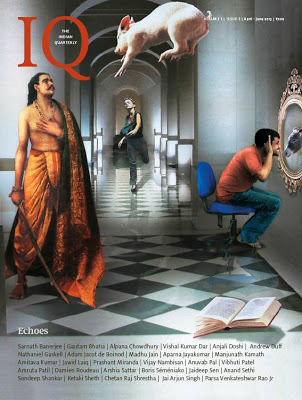

Trains in Indian cinema - an essay

The new issue of the magazine The Indian Quarterly is in bookstores now. I have an essay in it about the use of trains - as harbingers of love, tragedy, development and action - in Indian cinema. Had fun writing it, and reviving my own memories of "Gaadi Bula Rahi Hai", Half Ticket, The Burning Train, the chook-chook song from Aashirwad, the train as a hypnotic black serpent in the Apu Trilogy, and many other films. Do look out for the magazine. (There isn’t an updated website for it yet, but you can see some of the pieces from the first issue at this link. The Facebook page is here, and subscription information is available at theindianquarterlyATgmail.com.)

P.S. Somewhat related – here is a piece I did about the 1973 film 27 Down, about a man who measures his lives in train journeys. And here is an old post about The Burning Train (also known as The Turning Brain for the effect it has been known to have on audiences’ minds).

Published on June 01, 2013 05:53

May 29, 2013

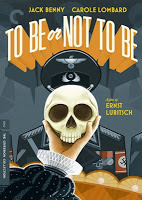

Heil harebrain: how comedy can make villains look ridiculous

I have written before about the Criterion Collection DVDs and their use of imaginative artwork to pay homage to great movies. Last week I learnt that the Satyajit Ray classics Charulata and Mahanagar will soon be out on Criterion, but equally pleasing was a glimpse of the cover design for Ernst Lubitsch’s brilliant 1942 comedy To Be or Not to Be . The picture on the DVD package juxtaposes a famous image from Hamlet - the glum prince, primed for a soliloquy, holding Yorick’s skull in his hand - with a figure dressed in a smart Nazi uniform, so that the skull covers the Nazi's head. This image of fascism defeated, or made buffoonish, by theatre nicely catches the mood of a film about a Polish acting troupe outsmarting Hitler’s men. It also reminds me of what the critic David Thomson said: “If one side is making To Be or Not to Be in the middle of a war and the other is not – you know which side to root for.”

No intention of spoiling Lubitsch’s film for anyone who hasn’t seen it, but just as an appetiser, its opening sequence involves the apparent appearance of Hitler – alone – at a market corner in 1939 Warsaw. As he hesitantly surveys the shops and residents gape at him, a breathless voiceover – resembling nothing so much as a baseball-match commentary – goes:

No intention of spoiling Lubitsch’s film for anyone who hasn’t seen it, but just as an appetiser, its opening sequence involves the apparent appearance of Hitler – alone – at a market corner in 1939 Warsaw. As he hesitantly surveys the shops and residents gape at him, a breathless voiceover – resembling nothing so much as a baseball-match commentary – goes:

“He seems strangely unconcerned by all the excitement he's causing. Is he by any chance interested in Mr Maslowski’s delicatessen? That’s impossible! He’s a vegetarian. And yet, he doesn’t always stick to his diet. Sometimes he swallows whole countries. Does he want to eat up Poland too?”

More digs at the leader follow in the next few minutes: an actor (the man who was pretending to be Hitler in that opening scene) responds to salutes with a “Heil Myself”, and a little boy speculates that if a brandy took the name Napoleon, perhaps Hitler “will end up as a piece of cheese”.

Of course, To Be or Not to Be was scarcely the only Hollywood film of its time to lampoon the Fuehrer. One of my favourite “Hitler cameos” occurs in Preston Sturges’s 1944 comedy The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek , about a small-town girl who gives birth to sextuplets, a national record. As news spreads across America and the world, we see the dictator's furious reaction and a headline from a German newspaper reads “Hitler Demands Recount!” Tangential though the scene is to the film, it links Hitler with terminology associated with voting and democracy, presented here as a symbol of America’s moral superiority over Nazi Germany.

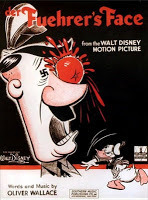

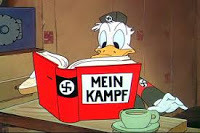

Around the same time, the good folks in animation were making more direct propaganda films such as the pleasingly titled

Herr Meets Hare

(in which Bugs Bunny accidentally tunnels to Germany while trying to find Las Vegas, and speaks incomprehensible faux-German in a shrill, Hitler-like voice),

Donald Duck in Nutzi Land

(the peevish Donald finds himself working in a Nazi factory, which makes him even more ill-tempered than usual) and

The Blitz Wolf

, which begins with the assertion “The Wolf in this photoplay is NOT fictitious. Any similarity between this Wolf and that (*!!#%) Hitler is purely intentional.”

Around the same time, the good folks in animation were making more direct propaganda films such as the pleasingly titled

Herr Meets Hare

(in which Bugs Bunny accidentally tunnels to Germany while trying to find Las Vegas, and speaks incomprehensible faux-German in a shrill, Hitler-like voice),

Donald Duck in Nutzi Land

(the peevish Donald finds himself working in a Nazi factory, which makes him even more ill-tempered than usual) and

The Blitz Wolf

, which begins with the assertion “The Wolf in this photoplay is NOT fictitious. Any similarity between this Wolf and that (*!!#%) Hitler is purely intentional.”Not all these films draw positive responses today. People are often affronted by Nazism being treated lightly in a Hollywood movie (or cartoon!), especially one that was made at a time when the very real horrors of the concentration camps were underway far across the Atlantic. One argument goes that it amounts to trivialising the Holocaust, and some things, we are told, should simply not be joked about. Well, I disagree in a broader sense with that idea – I don’t think any subject, however ugly or distasteful, should lie outside the purview of humour – but in this case the nature of the comedy serves an obviously desirable function: it strips a pompous, self-important figure of his dignity.

Recently there was a comparable scene in Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained

, where a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan, the white-supremacist group, turns into farce when the members find that they can’t see properly through the little slits in their white hoods; and these are the very costumes that they think make them look so awe-inspiring! The scene drags on too long, but one can’t fault its intention: undermining evil by making it banal, then ridiculous, so that by the end the group is more klutz than klux. (Incidentally, the real history of the KKK has an equivalent for this. In the 1940s, the author William Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the group and passed on its code-words for use in a children’s radio programme about Superman; as little children – including the children of mortified Klan members – began using the “secret words” in their games, the group’s air of mystery was diluted.)

Recently there was a comparable scene in Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained

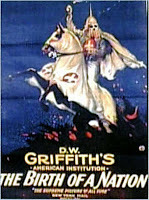

, where a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan, the white-supremacist group, turns into farce when the members find that they can’t see properly through the little slits in their white hoods; and these are the very costumes that they think make them look so awe-inspiring! The scene drags on too long, but one can’t fault its intention: undermining evil by making it banal, then ridiculous, so that by the end the group is more klutz than klux. (Incidentally, the real history of the KKK has an equivalent for this. In the 1940s, the author William Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the group and passed on its code-words for use in a children’s radio programme about Superman; as little children – including the children of mortified Klan members – began using the “secret words” in their games, the group’s air of mystery was diluted.)It is useful to have good satirical depictions of this sort in cinema, because there have already been films – powerful and influential and superbly made films – that have depicted evil in grand terms. Two that readily come to mind are Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will – a

document of Nazi rallies that begins with a stirring scene where Hitler is framed as a deity surveying his land from his plane before descending to make his speeches – and D W Griffith’s silent epic

The Birth of a Nation

, which portrayed the KKK almost as knights in shining white armour. The movies served different functions: Riefenstahl’s was explicit propaganda, made for the National Socialist Party, while Griffith – a Southerner who grew up with assumptions that we would consider very illiberal today – was possibly making an honest effort to capture the realities of a particular time. But their ability to sway audiences, to make violence and intolerance seem appealing, can’t be denied; think of Birth of a Nation audiences in 1915 watching new techniques such as fast-paced cross-cutting, which made the climactic action more rousing.

document of Nazi rallies that begins with a stirring scene where Hitler is framed as a deity surveying his land from his plane before descending to make his speeches – and D W Griffith’s silent epic

The Birth of a Nation

, which portrayed the KKK almost as knights in shining white armour. The movies served different functions: Riefenstahl’s was explicit propaganda, made for the National Socialist Party, while Griffith – a Southerner who grew up with assumptions that we would consider very illiberal today – was possibly making an honest effort to capture the realities of a particular time. But their ability to sway audiences, to make violence and intolerance seem appealing, can’t be denied; think of Birth of a Nation audiences in 1915 watching new techniques such as fast-paced cross-cutting, which made the climactic action more rousing. What films like To Be or Not to Be do is to provide a counterpoint by puncturing that balloon, and I’m thankful for them every time I see how fashionable it is for a certain demographic of Indian youngster (this includes a lot of management students, incidentally) to posture and claim fondness for Hitler’s Mein Kampf – a book that has long been a bestseller in India – or to express admiration for his “leadership qualities”.

What films like To Be or Not to Be do is to provide a counterpoint by puncturing that balloon, and I’m thankful for them every time I see how fashionable it is for a certain demographic of Indian youngster (this includes a lot of management students, incidentally) to posture and claim fondness for Hitler’s Mein Kampf – a book that has long been a bestseller in India – or to express admiration for his “leadership qualities”.That said, good comedy can have morally ambiguous consequences too, as can be seen in the viral popularity of the “Downfall spoofs” on the internet. Using a scene from the 2004 film Downfall – a serious treatment of Hitler’s final days – where the dictator becomes unhinged as he realises defeat is at hand, these videos rewrite the English subtitles to make it seem like Hitler is ranting about sundry inconveniences and oddities of the modern world: thus, “Hitler finds out that Twitter is down again” and “Hitler discovers that Oasis have split up”. Many of the results

are hysterically funny, but you might wonder about the implications: what does it say about us when a mass-murderer becomes a fellow pilgrim in expressing rage at relatively minor things? Empathy can be a tricky thing: these videos make Hitler one of us, and remind me of another exchange in To Be or Not to Be, when the director of the play expresses doubt about the effectiveness of the actor playing the dictator: “It’s not convincing. To me he’s just a man with a little moustache.” The actor replies: “But so is Hitler.”

are hysterically funny, but you might wonder about the implications: what does it say about us when a mass-murderer becomes a fellow pilgrim in expressing rage at relatively minor things? Empathy can be a tricky thing: these videos make Hitler one of us, and remind me of another exchange in To Be or Not to Be, when the director of the play expresses doubt about the effectiveness of the actor playing the dictator: “It’s not convincing. To me he’s just a man with a little moustache.” The actor replies: “But so is Hitler.”[Did a version of this for my DNA column]

Published on May 29, 2013 09:40

May 24, 2013

A playful book and a sober film - thoughts on The Reluctant Fundamentalist

A few years ago, during this long conversation about his novel

The Reluctant Fundamentalist

, the Pakistani writer Mohsin Hamid told me that the idea of art as artifice – “as a frame that is playful and stylised” – was important to him. The book is about a Pakistani man named Changez who goes to the US to study in Princeton, gets a job with a valuation firm, feels empowered by the American ideals of opportunity and equality – but finds himself becoming more defensive about his cultural identity in a divided, post-9/11 world. Importantly, this story is told in an abstract way: it takes the form of a long monologue addressed by Changez – now back in Pakistan – to an unnamed and voiceless American tourist, who becomes a stand-in for the reader. Changez’s tone is exaggeratedly courtly (“Excuse me, sir, but may I be of assistance? Ah, I see I have alarmed you. Do not be frightened by my beard: I am a lover of America”) with a possible undercurrent of threat, so that the reader can’t quite tell what his intentions are, and what the eventual result of this meeting might be.

Actually, the meeting need not even be taken at face value; it could simply be a storytelling device akin to the use of a sutradhaar or a katha-vaachak. “The effect I was reaching for,” Hamid told me, “is that you’re in a theatre and there’s one actor on the stage taking you through the play.” Watching a film in a large darkened room packed with strangers is an unnatural experience by its very construct, he pointed out. “Similarly, in a book, which is a packaged good, why can you not have an intermediary who allows you as a reader to move from your own world into the world of the narrative, while discussing that movement?”

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan.

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan.

Does it work? Yes and no. The film, which is an earnest attempt to bridge the gap between civilisations in our troubled times (from the beginning, Nair seems to have been very conscious about dealing with a Big Theme and about her role as a healer and facilitator), has some beautiful things in it. I liked the use of music, which incorporates Sufi motifs with western ones (the end-credits composition by Peter Gabriel is very effective) and laterally comments on the action: a line from the great poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, translated as “I don’t want this Kingdom, Lord / All I want is a grain of respect” plays over a scene where Changez decides to relinquish his US job and return home. And Riz Ahmed brings a lot of dignity to a difficult role; a lesser performance could have completely sunk the film.

However, transferring an allegorical novel to a visual medium – and thereby literalising it – can be a tricky business. Theoretically it should be possible to watch the film on its own terms, as an independent creation, but this is not always easy, given the more obvious symbolism in Hamid’s story - for example, the main female character is named "Erica", a clear stand-in for America, which Changez is unable to truly possess or take stock of. Such devices are tied to the abstractness of the novel and can seem heavy-handed in a film that adopts an otherwise realist structure. (This is not, after all, a Bunuel or Godard movie.)

Still, whatever you think of the book and the film, this is on many levels an interesting test case in the adaptation process and in an understanding of the differences between literature and cinema. A new book, The Reluctant Fundamentalist: From Book to Film , contains short accounts of the film’s making through the eyes of Nair and crew members including screenwriter Ami Boghani, production designer Michael Carlin and editor Shimit Amin. But some of the most entertaining footnotes come from Mohsin Hamid himself, as he reflects on novel-writing and filmmaking. “For me a day’s work is like entering a quiet, sheltered, unhurried cocoon,” he notes, “For a director it’s like talking on three different cellphones while riding a unicycle on the wing of an airplane in heavy turbulence.”

[Did a version of this for Business Standard. An earlier post on adaptation here, including notes from a short chat with Hamid two years ago, while the film was being made]

Actually, the meeting need not even be taken at face value; it could simply be a storytelling device akin to the use of a sutradhaar or a katha-vaachak. “The effect I was reaching for,” Hamid told me, “is that you’re in a theatre and there’s one actor on the stage taking you through the play.” Watching a film in a large darkened room packed with strangers is an unnatural experience by its very construct, he pointed out. “Similarly, in a book, which is a packaged good, why can you not have an intermediary who allows you as a reader to move from your own world into the world of the narrative, while discussing that movement?”

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan.

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan. Does it work? Yes and no. The film, which is an earnest attempt to bridge the gap between civilisations in our troubled times (from the beginning, Nair seems to have been very conscious about dealing with a Big Theme and about her role as a healer and facilitator), has some beautiful things in it. I liked the use of music, which incorporates Sufi motifs with western ones (the end-credits composition by Peter Gabriel is very effective) and laterally comments on the action: a line from the great poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, translated as “I don’t want this Kingdom, Lord / All I want is a grain of respect” plays over a scene where Changez decides to relinquish his US job and return home. And Riz Ahmed brings a lot of dignity to a difficult role; a lesser performance could have completely sunk the film.

However, transferring an allegorical novel to a visual medium – and thereby literalising it – can be a tricky business. Theoretically it should be possible to watch the film on its own terms, as an independent creation, but this is not always easy, given the more obvious symbolism in Hamid’s story - for example, the main female character is named "Erica", a clear stand-in for America, which Changez is unable to truly possess or take stock of. Such devices are tied to the abstractness of the novel and can seem heavy-handed in a film that adopts an otherwise realist structure. (This is not, after all, a Bunuel or Godard movie.)

Still, whatever you think of the book and the film, this is on many levels an interesting test case in the adaptation process and in an understanding of the differences between literature and cinema. A new book, The Reluctant Fundamentalist: From Book to Film , contains short accounts of the film’s making through the eyes of Nair and crew members including screenwriter Ami Boghani, production designer Michael Carlin and editor Shimit Amin. But some of the most entertaining footnotes come from Mohsin Hamid himself, as he reflects on novel-writing and filmmaking. “For me a day’s work is like entering a quiet, sheltered, unhurried cocoon,” he notes, “For a director it’s like talking on three different cellphones while riding a unicycle on the wing of an airplane in heavy turbulence.”

[Did a version of this for Business Standard. An earlier post on adaptation here, including notes from a short chat with Hamid two years ago, while the film was being made]

Published on May 24, 2013 04:32

Playful book, sober film - thoughts on The Reluctant Fundamentalist

A few years ago, during this long conversation about his novel

The Reluctant Fundamentalist

, the Pakistani writer Mohsin Hamid told me that the idea of art as artifice – “as a frame that is playful and stylised” – was important to him. The book is about a Pakistani man named Changez who goes to the US to study in Princeton, gets a job with a valuation firm, feels empowered by the American ideals of opportunity and equality – but finds himself becoming more defensive about his cultural identity in a divided, post-9/11 world. Importantly, this story is told in an abstract way: it takes the form of a long monologue addressed by Changez – now back in Pakistan – to an unnamed and voiceless American tourist, who becomes a stand-in for the reader. Changez’s tone is exaggeratedly courtly (“Excuse me, sir, but may I be of assistance? Ah, I see I have alarmed you. Do not be frightened by my beard: I am a lover of America”) with a possible undercurrent of threat, so that the reader can’t quite tell what his intentions are, and what the eventual result of this meeting might be.

Actually, the meeting need not even be taken at face value; it could simply be a storytelling device akin to the use of a sutradhaar or a katha-vaachak. “The effect I was reaching for,” Hamid told me, “is that you’re in a theatre and there’s one actor on the stage taking you through the play.” Watching a film in a large darkened room packed with strangers is an unnatural experience by its very construct, he pointed out. “Similarly, in a book, which is a packaged good, why can you not have an intermediary who allows you as a reader to move from your own world into the world of the narrative, while discussing that movement?”

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan.

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan.

Does it work? Yes and no. The film, which is an earnest attempt to bridge the gap between civilisations in our troubled times (Nair seems to have been very conscious from the beginning about dealing with a Big Theme and about her role as a healer and facilitator), has some beautiful things in it. I liked the use of music, which incorporates Sufi motifs with western ones (the end-credits composition by Peter Gabriel is very effective) and laterally comments on the action: a line from the great poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, translated as “I don’t want this Kingdom, Lord / All I want is a grain of respect” plays over a scene where Changez decides to relinquish his US job and return home. And Riz Ahmed brings a lot of dignity to a difficult role; a lesser performance could have completely sunk the film.

However, transferring an allegorical novel to a visual medium – and thereby literalising it – can be a tricky business. Theoretically it should be possible to watch the film on its own terms, as an independent creation, but this is not always easy, given the more obvious symbolism in Hamid’s story - for example, the main female character is named "Erica", a clear stand-in for America, which Changez is unable to truly possess or take stock of. Such devices are tied to the abstractness of the novel and can seem heavy-handed in a film that adopts an otherwise realist structure. (This is not, after all, a Bunuel or Godard movie.)

Still, whatever you think of the book and the film, this is on many levels an interesting test case in the adaptation process and in an understanding of the differences between literature and cinema. A new book, The Reluctant Fundamentalist: From Book to Film , contains short accounts of the film’s making through the eyes of Nair and crew members including screenwriter Ami Boghani, production designer Michael Carlin and editor Shimit Amin. But some of the most entertaining footnotes come from Mohsin Hamid himself, as he reflects on novel-writing and filmmaking. “For me a day’s work is like entering a quiet, sheltered, unhurried cocoon,” he notes, “For a director it’s like talking on three different cellphones while riding a unicycle on the wing of an airplane in heavy turbulence.”

[Did a version of this for Business Standard. An earlier post on adaptation here, including notes from a short chat with Hamid two years ago, while the film was being made]

Actually, the meeting need not even be taken at face value; it could simply be a storytelling device akin to the use of a sutradhaar or a katha-vaachak. “The effect I was reaching for,” Hamid told me, “is that you’re in a theatre and there’s one actor on the stage taking you through the play.” Watching a film in a large darkened room packed with strangers is an unnatural experience by its very construct, he pointed out. “Similarly, in a book, which is a packaged good, why can you not have an intermediary who allows you as a reader to move from your own world into the world of the narrative, while discussing that movement?”

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan.

It is ironical that Hamid used a cinematic analogy to discuss the “unreality” of his narrative structure, for Mira Nair’s new movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist has made the story less circular, and more like a conventional narrative. For Hamid, the very nature of his dramatic monologue implied a bias: the reader only hears the Pakistani side, the American never speaks. But Nair clearly wanted a more balanced approach, and her key change is to provide a context to the meeting between Changez and the American, doing away with the latter’s formlessness and giving him a distinct identity, voice and purpose. This inevitably also meant expanding the bits of the story set in Pakistan. Does it work? Yes and no. The film, which is an earnest attempt to bridge the gap between civilisations in our troubled times (Nair seems to have been very conscious from the beginning about dealing with a Big Theme and about her role as a healer and facilitator), has some beautiful things in it. I liked the use of music, which incorporates Sufi motifs with western ones (the end-credits composition by Peter Gabriel is very effective) and laterally comments on the action: a line from the great poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, translated as “I don’t want this Kingdom, Lord / All I want is a grain of respect” plays over a scene where Changez decides to relinquish his US job and return home. And Riz Ahmed brings a lot of dignity to a difficult role; a lesser performance could have completely sunk the film.

However, transferring an allegorical novel to a visual medium – and thereby literalising it – can be a tricky business. Theoretically it should be possible to watch the film on its own terms, as an independent creation, but this is not always easy, given the more obvious symbolism in Hamid’s story - for example, the main female character is named "Erica", a clear stand-in for America, which Changez is unable to truly possess or take stock of. Such devices are tied to the abstractness of the novel and can seem heavy-handed in a film that adopts an otherwise realist structure. (This is not, after all, a Bunuel or Godard movie.)

Still, whatever you think of the book and the film, this is on many levels an interesting test case in the adaptation process and in an understanding of the differences between literature and cinema. A new book, The Reluctant Fundamentalist: From Book to Film , contains short accounts of the film’s making through the eyes of Nair and crew members including screenwriter Ami Boghani, production designer Michael Carlin and editor Shimit Amin. But some of the most entertaining footnotes come from Mohsin Hamid himself, as he reflects on novel-writing and filmmaking. “For me a day’s work is like entering a quiet, sheltered, unhurried cocoon,” he notes, “For a director it’s like talking on three different cellphones while riding a unicycle on the wing of an airplane in heavy turbulence.”

[Did a version of this for Business Standard. An earlier post on adaptation here, including notes from a short chat with Hamid two years ago, while the film was being made]

Published on May 24, 2013 04:32

May 22, 2013

Helter Skelter's New Writing anthology

The online magazine Helter Skelter is inviting submissions for volume 3 of its New Writing anthology. I'm one of the judges; the theme this time is "Strange Love", and the submission guidelines and other details are here. Do pass the word around to anyone who might be interested.

Published on May 22, 2013 23:03

Column links

Might not be updating the blog very regularly in the coming weeks, but here's something I've been meaning to do for a while: put up links, where available, to archives of my columns/features on other publications' websites. To an extent this is redundant, because expanded versions of most of those pieces are already on the blog. But I like the idea of having a few quick-access external links, now that some newspapers and magazines have competent websites (and since I don't have a properly organised archive on this one). So here goes:

The old Yahoo India film column. (Note: one link on the first page is a mistake. I know nothing about "underreported Sensex P/E ratios".)

My Sunday Guardian books column (along with a few stand-alone reviews). Again, there are multiple pages.

Columns and reviews on the Business Standard website (which, believe it or not, looks marginally better than it did for the best part of the last decade). There seem to be dozens of pages here, and they include detritus from a light column I once did called "Neterati" (about the vagaries of online discourse) as well as sketchy opinion pieces that I now utterly disown. And, mortifyingly, some of the hurriedly-thrown-together listings I put together for a weekend books page back in the day.

Features/profiles for Caravan magazine.

Will add more as I find them, and also make them a permanent part of the blog layout at some point.

The old Yahoo India film column. (Note: one link on the first page is a mistake. I know nothing about "underreported Sensex P/E ratios".)