Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 71

January 11, 2014

Maa ka apmaan – on Nirupa Roy’s varicose veins and bandaged torso

Spent some time at the National Film Archive library in Pune this week, and wish I had stayed longer – especially because, in my last hour there, I came across old 1950s issues of the magazine Film India, edited by the famously snarky Baburao Patel.

Couldn’t go through as many issues as I would have liked, but there was time enough to note that Mr Patel really did seem to enjoy mocking poor Nirupa Roy in the mid-50s (she was a couple of decades away from her iconic “mother” roles, but was well known for playing homely bhabhis in family dramas, or pious characters in mythological films). When I fondly called her a land mammal in this essay, I feared it might be considered disrespectful, but Baburao Patel was in on the act decades earlier: I saw at least eight photos of Ms Roy with sarcastic captions. Here are just two (both from the same issue of the magazine):

(Click pics to enlarge)

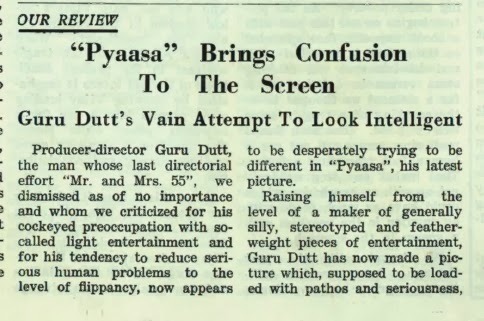

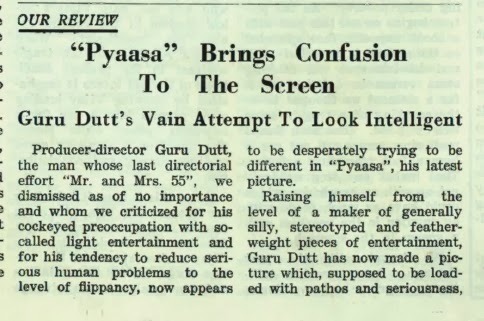

And as a bonus, the opening page (with headline and intro) of Film India’s review of the just-released Pyaasa:

P.S. an earlier post that serendipitously begins with references to both Nirupa Roy and Pyaasa is here.

Couldn’t go through as many issues as I would have liked, but there was time enough to note that Mr Patel really did seem to enjoy mocking poor Nirupa Roy in the mid-50s (she was a couple of decades away from her iconic “mother” roles, but was well known for playing homely bhabhis in family dramas, or pious characters in mythological films). When I fondly called her a land mammal in this essay, I feared it might be considered disrespectful, but Baburao Patel was in on the act decades earlier: I saw at least eight photos of Ms Roy with sarcastic captions. Here are just two (both from the same issue of the magazine):

(Click pics to enlarge)

And as a bonus, the opening page (with headline and intro) of Film India’s review of the just-released Pyaasa:

P.S. an earlier post that serendipitously begins with references to both Nirupa Roy and Pyaasa is here.

Published on January 11, 2014 01:25

December 30, 2013

Stuart Little and the Pandavas in the house of lac

Imagine my delight when I checked the Tata Sky synopses for this week’s episodes of the Mahabharat and saw the following summary for Wednesday (episode 77):

Now I feel like I have a moral responsibility to write similar 3-sentence synopses for future episodes: the first sentence should be a non-sequitur, or at least have no obvious connection with the main narrative, while the remaining two sentences should solemnly continue the plot at snail’s pace. For example –

Episode 78: Bhima and the rat jive to the beat of “I'm Alive”. The Pandavas wonder why the walls smell of oil and fat. Vidura tells his men to dig a tunnel.

Episode 79: Vyasa is very angry with the Star Plus writers. Sahadeva says there is no smoke without fire. The Pandavas uncover the plot to burn down the palace with them in it.

Episode 80: Arjuna goes for target practice, but someone with sharp teeth has nibbled through the bow-string. Vidura informs Bheeshma about his plan. Bheeshma sighs deeply.

Episode 80: Arjuna goes for target practice, but someone with sharp teeth has nibbled through the bow-string. Vidura informs Bheeshma about his plan. Bheeshma sighs deeply.

Episode 81: The rat considers moving somewhere safer, like the Bigg Boss house. The tunnel is half-finished. The workers take a lunch break and discuss the wickedness of the Kauravas.

Episode 82: Devdutt Pattanaik tells the rat dharma is subtle. Shakuni sends Purochana another secret message. Yudhisthira adjusts his crown and wonders if he should light a candle.

Teaser for the week after: Will the mouse douse the burning house? Find out in episode 83! Or episode 95!

(And so on. Feel free to weigh in. The epic is limitless and malleable, we must keep adding to it.)

[An earlier post: Karna and Kryptonite]

Now I feel like I have a moral responsibility to write similar 3-sentence synopses for future episodes: the first sentence should be a non-sequitur, or at least have no obvious connection with the main narrative, while the remaining two sentences should solemnly continue the plot at snail’s pace. For example –

Episode 78: Bhima and the rat jive to the beat of “I'm Alive”. The Pandavas wonder why the walls smell of oil and fat. Vidura tells his men to dig a tunnel.

Episode 79: Vyasa is very angry with the Star Plus writers. Sahadeva says there is no smoke without fire. The Pandavas uncover the plot to burn down the palace with them in it.

Episode 80: Arjuna goes for target practice, but someone with sharp teeth has nibbled through the bow-string. Vidura informs Bheeshma about his plan. Bheeshma sighs deeply.

Episode 80: Arjuna goes for target practice, but someone with sharp teeth has nibbled through the bow-string. Vidura informs Bheeshma about his plan. Bheeshma sighs deeply. Episode 81: The rat considers moving somewhere safer, like the Bigg Boss house. The tunnel is half-finished. The workers take a lunch break and discuss the wickedness of the Kauravas.

Episode 82: Devdutt Pattanaik tells the rat dharma is subtle. Shakuni sends Purochana another secret message. Yudhisthira adjusts his crown and wonders if he should light a candle.

Teaser for the week after: Will the mouse douse the burning house? Find out in episode 83! Or episode 95!

(And so on. Feel free to weigh in. The epic is limitless and malleable, we must keep adding to it.)

[An earlier post: Karna and Kryptonite]

Published on December 30, 2013 07:53

December 28, 2013

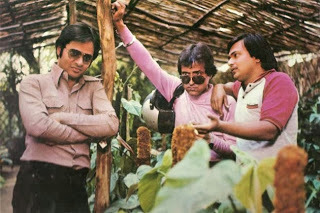

A memory of Farooque Shaikh

Less than a week before I heard the saddening – and most unexpected – news of Farooque Shaikh’s passing, an SMS written in a familiar style lit up my phone screen. “Adaab,” it said. “Wish u a Merry Christmas, a Joyous New Year and a v happy life ahead. Best luck, always.” A few minutes later, the same message arrived again. This could have been a network glitch, but having seen Mr Shaikh (or Farooque saab, as it seems more apt to call him) a few weeks earlier, wrestling with and frowning at his handset – something I can often relate to – I could picture him having re-sent it accidentally.

Either way, I had become used to the courtliness of his SMSes (even when written in shorthand) in the previous two months, ever since I first contacted him in connection with a writing project. In mid-October I had texted him – in the supplicating tone of a journalist seeking a few minutes of an Important Person’s time – asking if we could speak for a short while; on the phone would be fine. He replied with an “Adaab sir”, adding that he happened to be coming to Delhi at the end of the week, and it “wd be a plzre” to meet then “at a mutually cnvnnt time”.

Either way, I had become used to the courtliness of his SMSes (even when written in shorthand) in the previous two months, ever since I first contacted him in connection with a writing project. In mid-October I had texted him – in the supplicating tone of a journalist seeking a few minutes of an Important Person’s time – asking if we could speak for a short while; on the phone would be fine. He replied with an “Adaab sir”, adding that he happened to be coming to Delhi at the end of the week, and it “wd be a plzre” to meet then “at a mutually cnvnnt time”.

We met, and it was a pleasure – for me, at least – even though the conversation was short and unexceptional. He was everything you’d expect from his screen persona, warm and unfailingly polite in his direct addresses, though he did get a little agitated when he spoke more generally about falling standards in popular culture. I had a couple of specific talking points to cover, but we were quickly done with those, and for the next half-hour he talked mainly about how commerce had completely taken over the film world, and expressed annoyance about the hegemony of the Rs 200-300-crore cinema. “Vaahiyaat filmein agar 300 crore ka business kar rahe hain, toh aur log aa jaayenge, and they will go down the same route.”

Much of what he said – if you simply transcribed it – would read as relentless complaining, and I didn’t agree with all of it. Some of it mixed deep idealism, a yearning for a fabled past where things were always so much better than today, and (in the context of his thoughts on “good” and “bad” cinema) a narrow view of the relationship between subject and form. There were capricious asides: while making the (reasonable) point about Hollywood’s technical excellence masking deficiencies in content and not allowing any other type of film to get breathing space, he suddenly brought up films “jiss mein spaceship yun zor zor se awaaz karti hai, phir girne lagti hai – whereas it is a basic fact of zero gravity that a spaceship will not fall like that even if it breaks up.” And he clearly wasn’t a fan of Jaws and the summer-blockbuster culture it spawned: “Ya toh ek machli aisi hai jo logon ko khaamakhaa marne lagti hai. This kind of stupidity has to stop.”

Much of what he said – if you simply transcribed it – would read as relentless complaining, and I didn’t agree with all of it. Some of it mixed deep idealism, a yearning for a fabled past where things were always so much better than today, and (in the context of his thoughts on “good” and “bad” cinema) a narrow view of the relationship between subject and form. There were capricious asides: while making the (reasonable) point about Hollywood’s technical excellence masking deficiencies in content and not allowing any other type of film to get breathing space, he suddenly brought up films “jiss mein spaceship yun zor zor se awaaz karti hai, phir girne lagti hai – whereas it is a basic fact of zero gravity that a spaceship will not fall like that even if it breaks up.” And he clearly wasn’t a fan of Jaws and the summer-blockbuster culture it spawned: “Ya toh ek machli aisi hai jo logon ko khaamakhaa marne lagti hai. This kind of stupidity has to stop.”

But the discontent came from his strong views on the relationship between a society and its popular culture, and his keenness to fix responsibility. “Cinema is a willing or unwilling appendage to society, so we may as well have some quality in it. Otherwise it’s like saying ‘Naashta toh mujhe karna hi hai, sada hua bhi chalega.’ But why not have a good meal, even if it is a small one? You risk your health if you eat chaat all the time. And then we complain ‘hamaaray society mein auraton ke saath yeh hota hai.’ You can’t pretend that cinema doesn’t have an effect on our minds – it’s a big thing.”

It wasn’t all about venting though. The meeting reminded me of conversations I had had with other, very likable men of integrity of his generation, Kundan Shah and the late Ravi Baswani – a tone that combined irritation and frustration with the ability to step back after a while and crack a quiet joke about one’s own irritability. And a genuine, boyish curiosity about what the younger person sitting in front of them felt about these things. (I have memories of Kundan, Ravi and Farooque saab – separately, of course – pausing for breath after a rant, then chuckling and asking a version of the question “Do you agree with any of this? Or could it be that I feel this way only because main budhaa ho gaya hoon?” And the question was asked sincerely, not rhetorically.)

It wasn’t all about venting though. The meeting reminded me of conversations I had had with other, very likable men of integrity of his generation, Kundan Shah and the late Ravi Baswani – a tone that combined irritation and frustration with the ability to step back after a while and crack a quiet joke about one’s own irritability. And a genuine, boyish curiosity about what the younger person sitting in front of them felt about these things. (I have memories of Kundan, Ravi and Farooque saab – separately, of course – pausing for breath after a rant, then chuckling and asking a version of the question “Do you agree with any of this? Or could it be that I feel this way only because main budhaa ho gaya hoon?” And the question was asked sincerely, not rhetorically.)

Farooque saab spoke with pragmatism (“it is unreal, and perhaps even unfair, to expect that a filmmaker is going to do good to society at a loss to himself”) but perhaps had an unrealistic view of the power wielded by the “thinking” audience (“...and so the discerning viewer has to make his presence felt. With the internet you can get back to the filmmaker immediately if he has made a bad or bawdy film, and tell him off. He will take that seriously. He depends on the ticket that the viewer buys.”) He moved between optimism and cynicism (“But as is the norm all over the world, the major audience is males aged between 15 and 25 years. They are the ones who decide whether a film will run or not”) and used humorous analogies: “Aaj kal ke movie reviews mein star ratings aise bikhte hain jaise langar mein khaana bikh raha ho.” And “You know the Sea Link in Mumbai? It cuts down travel time dramatically while you are on it – but when you exit it you’re in trouble again. That’s how the industry today is. Film toh complete ho jaati hai but then the intelligent, sincere filmmaker is in a surrounding that he cannot control: agar 3,500 screen kisi big-budget film ne le liye hain, then you get the one or two remaining shows, and the show time is such that your own wife won’t go for it.”

Near the end of our chat, he – consciously or otherwise – used an analogy closely linked to the plot of one of his most beloved movies. “There are two people in the race – the sprinter and the evening walker,” he said, marking the difference between money-obsessed filmmakers and the ones with a social conscience. “The promenade walker will not get ahead because he isn’t in it for the race, he’s out for a stroll – the sprinter is the one who wants to get ahead, and he will always win.”

Near the end of our chat, he – consciously or otherwise – used an analogy closely linked to the plot of one of his most beloved movies. “There are two people in the race – the sprinter and the evening walker,” he said, marking the difference between money-obsessed filmmakers and the ones with a social conscience. “The promenade walker will not get ahead because he isn’t in it for the race, he’s out for a stroll – the sprinter is the one who wants to get ahead, and he will always win.”

In Sai Paranjpye’s Katha , based on the hare-and-tortoise fable, he was cast against type as the wily hare (or the sprinter). I alluded to the film and he merely nodded and gave a quick smile, not pursuing the point – he wasn’t much interested in talking about his own movies, or at least his contribution to them. When he brought up Listen…Amaya – as another low-budget film that was released in only a couple of halls – this is what he said: “Recently ek film thi, Listen... Amaya, jiss mein Deepti ji aur Swara Bhaskar thay...” No mention of himself.

Which may be a reminder that he wasn’t “in it for the race” himself. I have no doubt that he took a project seriously once he had committed to it, but he came across as being blasé about his own career, unconcerned with such things as staying in the public memory. Still, he had done some fine work in the past couple of years – in Shanghai, Listen…Amaya, even in his short part in Yeh Jawani hai Diwani – and there may have been more to come.

Still, he had done some fine work in the past couple of years – in Shanghai, Listen…Amaya, even in his short part in Yeh Jawani hai Diwani – and there may have been more to come.

I don’t usually get too affected by the deaths of public figures, even those whose work or achievements I admired. But this was a little different, because of the immediacy of having met him so recently, and because he was too young. Notwithstanding his own indifference to fame or plaudits, with the right mix of subject, writer and director he might easily have had a notable second innings as a screen actor. For now, we have the past work: old favourites like Chashme Buddoor and Katha, of course, but also films like Gaman (now available in a restored NFDC print) and Saath Saath, which deserve to be revisited and rediscovered. And I have the rueful knowledge that despite having had opportunities, I never got around to seeing a performance of Tumhari Amrita .

[Related posts: a tribute to Ravi Baswani, Shaikh’s co-star in Chashme Buddoor; a review of Sai Paranjpye’s Katha; a piece about Listen Amaya, and about watching Shaikh and Deepti Naval on screen together after all these years. And on two excellent films in which Shaikh had small parts, 40 years apart: Garm Hava and Shanghai]

Either way, I had become used to the courtliness of his SMSes (even when written in shorthand) in the previous two months, ever since I first contacted him in connection with a writing project. In mid-October I had texted him – in the supplicating tone of a journalist seeking a few minutes of an Important Person’s time – asking if we could speak for a short while; on the phone would be fine. He replied with an “Adaab sir”, adding that he happened to be coming to Delhi at the end of the week, and it “wd be a plzre” to meet then “at a mutually cnvnnt time”.

Either way, I had become used to the courtliness of his SMSes (even when written in shorthand) in the previous two months, ever since I first contacted him in connection with a writing project. In mid-October I had texted him – in the supplicating tone of a journalist seeking a few minutes of an Important Person’s time – asking if we could speak for a short while; on the phone would be fine. He replied with an “Adaab sir”, adding that he happened to be coming to Delhi at the end of the week, and it “wd be a plzre” to meet then “at a mutually cnvnnt time”.We met, and it was a pleasure – for me, at least – even though the conversation was short and unexceptional. He was everything you’d expect from his screen persona, warm and unfailingly polite in his direct addresses, though he did get a little agitated when he spoke more generally about falling standards in popular culture. I had a couple of specific talking points to cover, but we were quickly done with those, and for the next half-hour he talked mainly about how commerce had completely taken over the film world, and expressed annoyance about the hegemony of the Rs 200-300-crore cinema. “Vaahiyaat filmein agar 300 crore ka business kar rahe hain, toh aur log aa jaayenge, and they will go down the same route.”

Much of what he said – if you simply transcribed it – would read as relentless complaining, and I didn’t agree with all of it. Some of it mixed deep idealism, a yearning for a fabled past where things were always so much better than today, and (in the context of his thoughts on “good” and “bad” cinema) a narrow view of the relationship between subject and form. There were capricious asides: while making the (reasonable) point about Hollywood’s technical excellence masking deficiencies in content and not allowing any other type of film to get breathing space, he suddenly brought up films “jiss mein spaceship yun zor zor se awaaz karti hai, phir girne lagti hai – whereas it is a basic fact of zero gravity that a spaceship will not fall like that even if it breaks up.” And he clearly wasn’t a fan of Jaws and the summer-blockbuster culture it spawned: “Ya toh ek machli aisi hai jo logon ko khaamakhaa marne lagti hai. This kind of stupidity has to stop.”

Much of what he said – if you simply transcribed it – would read as relentless complaining, and I didn’t agree with all of it. Some of it mixed deep idealism, a yearning for a fabled past where things were always so much better than today, and (in the context of his thoughts on “good” and “bad” cinema) a narrow view of the relationship between subject and form. There were capricious asides: while making the (reasonable) point about Hollywood’s technical excellence masking deficiencies in content and not allowing any other type of film to get breathing space, he suddenly brought up films “jiss mein spaceship yun zor zor se awaaz karti hai, phir girne lagti hai – whereas it is a basic fact of zero gravity that a spaceship will not fall like that even if it breaks up.” And he clearly wasn’t a fan of Jaws and the summer-blockbuster culture it spawned: “Ya toh ek machli aisi hai jo logon ko khaamakhaa marne lagti hai. This kind of stupidity has to stop.”But the discontent came from his strong views on the relationship between a society and its popular culture, and his keenness to fix responsibility. “Cinema is a willing or unwilling appendage to society, so we may as well have some quality in it. Otherwise it’s like saying ‘Naashta toh mujhe karna hi hai, sada hua bhi chalega.’ But why not have a good meal, even if it is a small one? You risk your health if you eat chaat all the time. And then we complain ‘hamaaray society mein auraton ke saath yeh hota hai.’ You can’t pretend that cinema doesn’t have an effect on our minds – it’s a big thing.”

It wasn’t all about venting though. The meeting reminded me of conversations I had had with other, very likable men of integrity of his generation, Kundan Shah and the late Ravi Baswani – a tone that combined irritation and frustration with the ability to step back after a while and crack a quiet joke about one’s own irritability. And a genuine, boyish curiosity about what the younger person sitting in front of them felt about these things. (I have memories of Kundan, Ravi and Farooque saab – separately, of course – pausing for breath after a rant, then chuckling and asking a version of the question “Do you agree with any of this? Or could it be that I feel this way only because main budhaa ho gaya hoon?” And the question was asked sincerely, not rhetorically.)

It wasn’t all about venting though. The meeting reminded me of conversations I had had with other, very likable men of integrity of his generation, Kundan Shah and the late Ravi Baswani – a tone that combined irritation and frustration with the ability to step back after a while and crack a quiet joke about one’s own irritability. And a genuine, boyish curiosity about what the younger person sitting in front of them felt about these things. (I have memories of Kundan, Ravi and Farooque saab – separately, of course – pausing for breath after a rant, then chuckling and asking a version of the question “Do you agree with any of this? Or could it be that I feel this way only because main budhaa ho gaya hoon?” And the question was asked sincerely, not rhetorically.)Farooque saab spoke with pragmatism (“it is unreal, and perhaps even unfair, to expect that a filmmaker is going to do good to society at a loss to himself”) but perhaps had an unrealistic view of the power wielded by the “thinking” audience (“...and so the discerning viewer has to make his presence felt. With the internet you can get back to the filmmaker immediately if he has made a bad or bawdy film, and tell him off. He will take that seriously. He depends on the ticket that the viewer buys.”) He moved between optimism and cynicism (“But as is the norm all over the world, the major audience is males aged between 15 and 25 years. They are the ones who decide whether a film will run or not”) and used humorous analogies: “Aaj kal ke movie reviews mein star ratings aise bikhte hain jaise langar mein khaana bikh raha ho.” And “You know the Sea Link in Mumbai? It cuts down travel time dramatically while you are on it – but when you exit it you’re in trouble again. That’s how the industry today is. Film toh complete ho jaati hai but then the intelligent, sincere filmmaker is in a surrounding that he cannot control: agar 3,500 screen kisi big-budget film ne le liye hain, then you get the one or two remaining shows, and the show time is such that your own wife won’t go for it.”

Near the end of our chat, he – consciously or otherwise – used an analogy closely linked to the plot of one of his most beloved movies. “There are two people in the race – the sprinter and the evening walker,” he said, marking the difference between money-obsessed filmmakers and the ones with a social conscience. “The promenade walker will not get ahead because he isn’t in it for the race, he’s out for a stroll – the sprinter is the one who wants to get ahead, and he will always win.”

Near the end of our chat, he – consciously or otherwise – used an analogy closely linked to the plot of one of his most beloved movies. “There are two people in the race – the sprinter and the evening walker,” he said, marking the difference between money-obsessed filmmakers and the ones with a social conscience. “The promenade walker will not get ahead because he isn’t in it for the race, he’s out for a stroll – the sprinter is the one who wants to get ahead, and he will always win.”In Sai Paranjpye’s Katha , based on the hare-and-tortoise fable, he was cast against type as the wily hare (or the sprinter). I alluded to the film and he merely nodded and gave a quick smile, not pursuing the point – he wasn’t much interested in talking about his own movies, or at least his contribution to them. When he brought up Listen…Amaya – as another low-budget film that was released in only a couple of halls – this is what he said: “Recently ek film thi, Listen... Amaya, jiss mein Deepti ji aur Swara Bhaskar thay...” No mention of himself.

Which may be a reminder that he wasn’t “in it for the race” himself. I have no doubt that he took a project seriously once he had committed to it, but he came across as being blasé about his own career, unconcerned with such things as staying in the public memory.

Still, he had done some fine work in the past couple of years – in Shanghai, Listen…Amaya, even in his short part in Yeh Jawani hai Diwani – and there may have been more to come.

Still, he had done some fine work in the past couple of years – in Shanghai, Listen…Amaya, even in his short part in Yeh Jawani hai Diwani – and there may have been more to come. I don’t usually get too affected by the deaths of public figures, even those whose work or achievements I admired. But this was a little different, because of the immediacy of having met him so recently, and because he was too young. Notwithstanding his own indifference to fame or plaudits, with the right mix of subject, writer and director he might easily have had a notable second innings as a screen actor. For now, we have the past work: old favourites like Chashme Buddoor and Katha, of course, but also films like Gaman (now available in a restored NFDC print) and Saath Saath, which deserve to be revisited and rediscovered. And I have the rueful knowledge that despite having had opportunities, I never got around to seeing a performance of Tumhari Amrita .

[Related posts: a tribute to Ravi Baswani, Shaikh’s co-star in Chashme Buddoor; a review of Sai Paranjpye’s Katha; a piece about Listen Amaya, and about watching Shaikh and Deepti Naval on screen together after all these years. And on two excellent films in which Shaikh had small parts, 40 years apart: Garm Hava and Shanghai]

Published on December 28, 2013 23:40

December 21, 2013

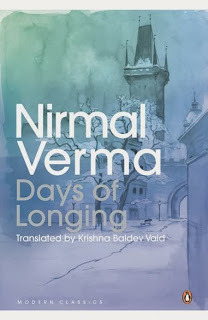

Love and longing in Prague - on Nirmal Verma's वे दिन

[Did this piece for the Sunday Guardian]

-------------

“Happiness always takes us by surprise, or perhaps it is not happiness. It is one’s unhappiness diminished in size.”

Is this a happy book or a sad book? The question sounds trite and reductive, but it leapt to mind as I turned the last page of Nirmal Verma’s Days of Longing, an English translation - by Krishna Baldev Vaid - of the 1964 novel वे दिन, now out in a new edition by Penguin’s Modern Classics. Depending on one’s perspective (and possibly depending on what stage of life one is in), this could be an essentially sad story disguised as something brighter, or the converse, a breezy, slice-of-life tale pretending to be a tragic love story. Either way, this is among the most moving novels I have read in a while – and in one sense at least, among the most unusual.

Is this a happy book or a sad book? The question sounds trite and reductive, but it leapt to mind as I turned the last page of Nirmal Verma’s Days of Longing, an English translation - by Krishna Baldev Vaid - of the 1964 novel वे दिन, now out in a new edition by Penguin’s Modern Classics. Depending on one’s perspective (and possibly depending on what stage of life one is in), this could be an essentially sad story disguised as something brighter, or the converse, a breezy, slice-of-life tale pretending to be a tragic love story. Either way, this is among the most moving novels I have read in a while – and in one sense at least, among the most unusual.Here is a book by an Indian writer, about an Indian student who has lived in cold Prague for over two years, and is spending the Christmas holidays (a time of year when overseas students typically go home) in the city, with the few friends who are still around: among them a Burmese student named Than Thun (TT), a restless German named Franz, who is studying cinematography but getting nowhere, and Franz’s girlfriend Maria, who is unable to get the visa that will allow her to leave the country with him. Much of their time is spent visiting pubs or lolling about in their gloomy hostel, drinking vodka or beer or sherry almost throughout the day, not so much to get drunk as to stay warm (as in so many Eastern European novels, the weather seems a constant factor in the characters’ lives, informing their actions and attitudes). They often go without hot water and don’t seem to sleep for more than a couple of hours, but subsist – more or less cheerfully – in each other’s company; they joke about living in “the city of empty pockets and full bladders” (because there are very few public urinals).

And through all this, the Indianness of the unnamed narrator-protagonist scarcely seems a factor at all***. For a reader used to the many soul-searching narratives about displacement or exile in Indian English fiction, this can be startling. We learn nothing about this young man’s family, his background, even which part of India he comes from. (For the longest time, I didn’t picture him as Indian at all; instead, drawing on a prior reference point for a story set in Czechoslovakia, I saw him as a version of the wide-eyed, sallow-complexioned Milos in the film

Closely Watched Trains

.) There is a mention of a letter from home, which he isn’t eager to open (“I remembered that I had not yet read my sister’s letter, but then I remembered that there was no light. I felt happy at the thought that I wouldn’t have to read it that night”), but it isn’t the case that something dramatic led him to “escape” to a foreign land – it is more as if he has settled into a cocoon beyond ideas of country or culture or nostalgia, a cocoon woven around new friendships. “We had left home at a stage when our childhood connections had been cut off and we hadn’t yet forged adult links with people and places,” he tells us, speaking of himself and TT, “Our homes seemed unreal from afar, like someone else’s homes, alien memories. They seemed meaningless, even ridiculous.”

And through all this, the Indianness of the unnamed narrator-protagonist scarcely seems a factor at all***. For a reader used to the many soul-searching narratives about displacement or exile in Indian English fiction, this can be startling. We learn nothing about this young man’s family, his background, even which part of India he comes from. (For the longest time, I didn’t picture him as Indian at all; instead, drawing on a prior reference point for a story set in Czechoslovakia, I saw him as a version of the wide-eyed, sallow-complexioned Milos in the film

Closely Watched Trains

.) There is a mention of a letter from home, which he isn’t eager to open (“I remembered that I had not yet read my sister’s letter, but then I remembered that there was no light. I felt happy at the thought that I wouldn’t have to read it that night”), but it isn’t the case that something dramatic led him to “escape” to a foreign land – it is more as if he has settled into a cocoon beyond ideas of country or culture or nostalgia, a cocoon woven around new friendships. “We had left home at a stage when our childhood connections had been cut off and we hadn’t yet forged adult links with people and places,” he tells us, speaking of himself and TT, “Our homes seemed unreal from afar, like someone else’s homes, alien memories. They seemed meaningless, even ridiculous.”Into this languid, drifting life comes the seed of a “plot” when the narrator (I’ll call him Indy for convenience, as his friends sometimes do) gets a temporary job as an interpreter for an Austrian woman named Raina and her little son. Indy and Raina grow close, and over the three days they spend together he experiences a range of emotions, swelling, then subsiding and swelling again: from hesitance and doubt to intense longing and awareness of hours spent apart, to quiet jealousy and possessiveness, built on the knowledge that her previous visit to Prague had been in the company of her now-estranged husband Jacques, and that she may be attempting to relive it by going to the same spots again.

“It bothered me,” he says, “I wanted her to look at everything for the first time. But she seemed to be keen about revisiting places she had already seen.” And then the simple yet powerful pathos of this line: “After knowing some people, one can’t help feeling one’s met them a bit too late.”

“It wasn’t age that separated us. It was her past, completely concealed from my knowledge. There are houses that you can’t really enter even through their wide open doors. They are alien, unpossessable.”

These could be the thoughts of anyone who has wondered about a lover’s romantic history, but here they also have to do with Raina’s experiences in the Second World War. It occurred to me that with a shift in narrative focus, this novel would strongly resemble William Styron’s

Sophie’s Choice

(which came 15 years later), about a young man besotted by an older woman but also permanently cut off from her by the terrible things she went through in the past, and unable to compete with the ineradicable, sado-masochistic relationship she has with the man who shared that past with her.

These could be the thoughts of anyone who has wondered about a lover’s romantic history, but here they also have to do with Raina’s experiences in the Second World War. It occurred to me that with a shift in narrative focus, this novel would strongly resemble William Styron’s

Sophie’s Choice

(which came 15 years later), about a young man besotted by an older woman but also permanently cut off from her by the terrible things she went through in the past, and unable to compete with the ineradicable, sado-masochistic relationship she has with the man who shared that past with her.Days of Longing is not as obviously driven by political events as Styron's novel – it is sparer, more abstract, more concerned with a young man’s interior life than with larger histories. Yet the shadows of those histories do loom in the background: in the brief allusions to WWII (Raina makes the strange but believable admission that her relationship with her husband, secure when they were living in turbulent, war-fractured times, began to dissolve when peace arrived), but also in the little reminders – through the parallel story of Franz and Maria, or a reference to a sad, accordion-playing hostel inmate who can’t go home to Belgrade to be with his family – of troubled relations between the European countries in the present day of the narrative. Throughout, there is a sense of how the personal is affected by the political.

And hanging over Indy and Raina is the knowledge of how short-lived their relationship is. In a sense, all their time together is preparation for being separated (not unlike the lovers in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise ) and the very temporariness makes it more intense, making him more aware of the need to hold on to things and remember them; to be seduced by the idea of love rather than the tangible presence of it. (“Remember the day we went to the skating rink?” she asks. It is an oddly put question on the face of it, since it refers to something that happened only 48 hours earlier. Yet it makes sense – they are trying to fit a lifetime of longing into this short period.)

In fact, a possible key to this book’s mysteries is a description of love as a temporary respite: “It was like an invisible fire that we could feel, that had been trying to pierce through our mutual darkness […] Three days or three years don’t make a difference unless we can catch hold of a burning moment in the darkness, knowing full well that it won’t last and after it is extinguished we will slide back into our own chilling solitude.” That burning moment set against darkness finds an echo elsewhere in the book. At one point Raina relates something she had once been told, about there being two kinds of happiness, big and small. Small happiness includes the warmth provided by fire or sherry, or the company of friends. “And the big happiness is to be able to breathe, just to be able to breathe in open air.” The words, tellingly, came from a Jewish man who was laughing and handing out cigarettes at the time, but was later killed by the Germans.

This elegant, hard-to-classify novel doesn’t quite provide a sense of closure or even development, which is why it is difficult to think of it as a coming-of-age story – it seems Indy’s life will continue along a circuit, much like the city’s trams gliding along their familiar routes (and perhaps I can call to mind here the ending of a favourite novel, also set in an Eastern European city, Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled). But perhaps his time with Raina has helped him come to terms with the crucial idea of “small” happiness, and the possibility that this romance, so all-encompassing while it unfolded, could in the larger view of things be just another addition to that list. Most of all, perhaps the lesson he is learning is that there may not be anything so grand or lasting as a big happiness.

-------------

*** Of course, the question arises: if one were reading this book in the original Hindi, would it be possible to "forget" or disregard Indy's Indianness? I imagine not, having read an excerpt from वे दिन on Pustak.org.

P.S.Krishna Baldev Vaid, a renowned writer himself, was a contemporary and sometime friend of Nirmal Verma; for a sense of Vaid’s often-ambivalent feelings about Verma and his work, read this tribute.

P.P.S. The Modern Classics imprint also has a new edition of The Red Tin Roof , a translation of Verma's लाल टीन की छत

Published on December 21, 2013 07:16

December 19, 2013

Notes from the Star Plus Mahabharata: Kryptonite Karna

I have been following the new Star Plus Mahabharata fairly closely, a process made easier by the fact that each episode is uploaded on YouTube a day after the telecast (though the more flamboyant action scenes are better seen on H-D TV). The show has its problems – as any five-day-a-week Mahabharata would – but it definitely isn’t bad, or unintentionally funny, in the way that Ekta Kapoor’s shoddy Kahaani Hamaaray Mahabharat Ki was***. Hope to do an extended post about it at some point (have written something in an essay for a magazine, which I will put up here soon), but for now a quick note about certain inventive things they have done to Karna. His impenetrable kavacha (armour) isn't permanently attached to his

body, as in the original epic. Instead it appears only in specific moments of crisis – when an arrow is headed for his chest, for instance. In this episode, you can see this happen twice: first, with the teenage Karna, around the four-minute mark; then with the first appearance of the adult Karna at the end of the episode, when a flaming thing comes at him out of the artificial sun he has created with his astra. (Yes!)

body, as in the original epic. Instead it appears only in specific moments of crisis – when an arrow is headed for his chest, for instance. In this episode, you can see this happen twice: first, with the teenage Karna, around the four-minute mark; then with the first appearance of the adult Karna at the end of the episode, when a flaming thing comes at him out of the artificial sun he has created with his astra. (Yes!)

These scenes put me in mind of modern comic-book superheroes with their secret powers – Clark Kent turning into Superman in the phone booth – and tight costumes worn over muscular abdomens. But there are parallels anyway: the Superman back-story has baby Kal-El being encased in a protective bubble by his father, much like Karna gets his kavacha from his divine daddy Surya. Watch this scene from the 1978 Superman and tell me you don’t recognise other rudiments of the story: the child being sent away by tearful parents (Marlon Brando as Kunti, who would’ve thunk?); the foster-parents being unable to come to grips with the apparently superhuman gifts of the infant they have raised in their humble home. And the armour will also turn out to be Karna’s Kryptonite when he has to give it away later in the tale. Another reminder that modern mythologies are so often derivative of ancient ones.

anyway: the Superman back-story has baby Kal-El being encased in a protective bubble by his father, much like Karna gets his kavacha from his divine daddy Surya. Watch this scene from the 1978 Superman and tell me you don’t recognise other rudiments of the story: the child being sent away by tearful parents (Marlon Brando as Kunti, who would’ve thunk?); the foster-parents being unable to come to grips with the apparently superhuman gifts of the infant they have raised in their humble home. And the armour will also turn out to be Karna’s Kryptonite when he has to give it away later in the tale. Another reminder that modern mythologies are so often derivative of ancient ones.

P.S. that episode I linked to also features Puneet Issar as Parashurama, allowing doddering folks of my vintage to feel deeply nostalgic about his performance as Duryodhana 25 years ago.

*** Some posts about Kahaani Hamaaray Mahabharat Ki: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Also, an old post that ponders the important question: why did Karna need to borrow vinegar from hairy and characterless women?

body, as in the original epic. Instead it appears only in specific moments of crisis – when an arrow is headed for his chest, for instance. In this episode, you can see this happen twice: first, with the teenage Karna, around the four-minute mark; then with the first appearance of the adult Karna at the end of the episode, when a flaming thing comes at him out of the artificial sun he has created with his astra. (Yes!)

body, as in the original epic. Instead it appears only in specific moments of crisis – when an arrow is headed for his chest, for instance. In this episode, you can see this happen twice: first, with the teenage Karna, around the four-minute mark; then with the first appearance of the adult Karna at the end of the episode, when a flaming thing comes at him out of the artificial sun he has created with his astra. (Yes!) These scenes put me in mind of modern comic-book superheroes with their secret powers – Clark Kent turning into Superman in the phone booth – and tight costumes worn over muscular abdomens. But there are parallels

anyway: the Superman back-story has baby Kal-El being encased in a protective bubble by his father, much like Karna gets his kavacha from his divine daddy Surya. Watch this scene from the 1978 Superman and tell me you don’t recognise other rudiments of the story: the child being sent away by tearful parents (Marlon Brando as Kunti, who would’ve thunk?); the foster-parents being unable to come to grips with the apparently superhuman gifts of the infant they have raised in their humble home. And the armour will also turn out to be Karna’s Kryptonite when he has to give it away later in the tale. Another reminder that modern mythologies are so often derivative of ancient ones.

anyway: the Superman back-story has baby Kal-El being encased in a protective bubble by his father, much like Karna gets his kavacha from his divine daddy Surya. Watch this scene from the 1978 Superman and tell me you don’t recognise other rudiments of the story: the child being sent away by tearful parents (Marlon Brando as Kunti, who would’ve thunk?); the foster-parents being unable to come to grips with the apparently superhuman gifts of the infant they have raised in their humble home. And the armour will also turn out to be Karna’s Kryptonite when he has to give it away later in the tale. Another reminder that modern mythologies are so often derivative of ancient ones.P.S. that episode I linked to also features Puneet Issar as Parashurama, allowing doddering folks of my vintage to feel deeply nostalgic about his performance as Duryodhana 25 years ago.

*** Some posts about Kahaani Hamaaray Mahabharat Ki: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Also, an old post that ponders the important question: why did Karna need to borrow vinegar from hairy and characterless women?

Published on December 19, 2013 09:48

December 14, 2013

A book about Sahir Ludhianvi

An early shout-out for

Sahir Ludhianvi: The People’s Poet

, written by Akshay Manwani and available for pre-order now. I have been following Akshay’s progress, on and off over the past few years, on what has been a labour of love for him, and am glad the book is finally ready: it should contribute to filling a gap in Indian writing in English, that of the serious biography of a modern cultural figure.

On December 18, I will be moderating a conversation with Akshay about the book at the India International Centre in Delhi: also on the panel is Gauhar Raza, the scientist and Urdu poet. The invite is below – do try to come, and spread the word to Sahir Ludhianvi fans. (Also, here are some links to Akshay’s long-form work on the Caravan website: profiles of Piyush Mishra and Irshad Kamil, as well as a piece about the 25th anniversary of the B R Chopra Mahabharata.)

On December 18, I will be moderating a conversation with Akshay about the book at the India International Centre in Delhi: also on the panel is Gauhar Raza, the scientist and Urdu poet. The invite is below – do try to come, and spread the word to Sahir Ludhianvi fans. (Also, here are some links to Akshay’s long-form work on the Caravan website: profiles of Piyush Mishra and Irshad Kamil, as well as a piece about the 25th anniversary of the B R Chopra Mahabharata.)

Published on December 14, 2013 21:25

December 10, 2013

On Jaspreet Singh's Helium, fiction as lecture, and the 1984 riots

[Did a shorter version of this for GQ India]

Being all of seven when the anti-Sikh riots following Indira Gandhi’s assassination took place, I don’t have vivid memories of the time, apart from knowing that my grandfather had to remove the “Singh” nameplate from outside our south Delhi residence. That must have been distressing enough for a proud man who had retired as a Brigadier in the Seventies, but it doesn’t compare to the horrors visited on other, less privileged – or less lucky – members of the community during those lawless days.

The writer Jaspreet Singh must have had a more immediate relationship with the tragedy: it is evident on nearly every angry, mournful page of his new novel

Helium

, written in the voice of a Hindu man returning to India after 25 years in the US. That quarter-century is a form of self-banishment: as a 19-year-old student in 1984, Raj witnessed the killing of his Sikh professor and later realised that his own father – a senior police officer – was complicit in the riots. But an even more complex guilt, rooted in Raj’s relationship with his professor’s attractive wife, may be at play. Now, decades later, he has returned to make sense of the past and possibly slay some of his demons. This is promising material for a novel, but Heliumtries to be too many things at once, which could be a pitfall inherent in its genre.

The writer Jaspreet Singh must have had a more immediate relationship with the tragedy: it is evident on nearly every angry, mournful page of his new novel

Helium

, written in the voice of a Hindu man returning to India after 25 years in the US. That quarter-century is a form of self-banishment: as a 19-year-old student in 1984, Raj witnessed the killing of his Sikh professor and later realised that his own father – a senior police officer – was complicit in the riots. But an even more complex guilt, rooted in Raj’s relationship with his professor’s attractive wife, may be at play. Now, decades later, he has returned to make sense of the past and possibly slay some of his demons. This is promising material for a novel, but Heliumtries to be too many things at once, which could be a pitfall inherent in its genre.

When fiction takes on real-world tragedies – especially manmade tragedies that are still fresh in the collective memory – it often happens that the grotesqueness of actual events becomes overwhelming; reality threatens to dwarf the novelist’s imaginative skills. This may be why so much writing of this sort moves beyond realist storytelling and employs surrealism, magic realism or jet-black humour: consider Mohammed Hanif’s A Case Of Exploding Mangoes , a dark satire about the twilight days of the Pakistani dictator Zia ul Haq, or Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat , about another real-life tyrant, the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo, or Raj Kamal Jha’s ambitious but overwritten Fireproof , which approaches the 2002 Gujarat riots tangentially, using the metaphor of a father saddled with a deformed baby on the day after the Godhra killings. By being deliberately over the top, such books often provide a buffer for the reader, shielding us from the full-on assaults of hard reality. But it goes without saying that such flourishes are inherently risky things – very few writers can pull them off with consistent success.

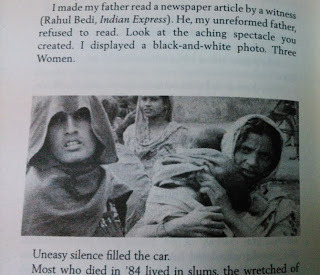

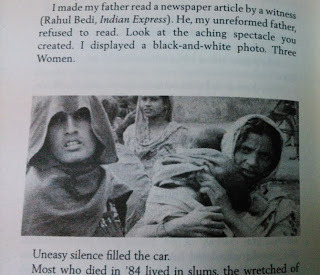

Heliummakes some intriguing stylistic choices too. Singh – who has studied chemical engineering – is deeply influenced by

The Periodic Table

, Primo Levi’s memoir about working as a chemist in fascist Germany: that book is an acknowledged guiding light for him, as he contrasts the shape and movements of chemical elements with the colliding paths and destinies of human beings. But the spirit of another major writer also inhabits these pages. Like W G Sebald, Singh is interested in the variability and unreliability of memory, and collective forgetfulness when it comes to human tragedies; like Sebald, he uses the method of interspersing text with black-and-white images, which testify to the inadequacy of mere writing when it comes to remembering. (Unlike Sebald, he links rheology – the study of the flow of matter – with the viscosity of memories, a natural enough association given Raj's profession and educational background.)

Heliummakes some intriguing stylistic choices too. Singh – who has studied chemical engineering – is deeply influenced by

The Periodic Table

, Primo Levi’s memoir about working as a chemist in fascist Germany: that book is an acknowledged guiding light for him, as he contrasts the shape and movements of chemical elements with the colliding paths and destinies of human beings. But the spirit of another major writer also inhabits these pages. Like W G Sebald, Singh is interested in the variability and unreliability of memory, and collective forgetfulness when it comes to human tragedies; like Sebald, he uses the method of interspersing text with black-and-white images, which testify to the inadequacy of mere writing when it comes to remembering. (Unlike Sebald, he links rheology – the study of the flow of matter – with the viscosity of memories, a natural enough association given Raj's profession and educational background.)

Reading Helium, I was also reminded of Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People, a fictionalised account of the aftermath of the Bhopal gas tragedy. Sinha’s novel, which begins with the words “I used to be human once”, is narrated by a misshapen youngster called Jaanvar because he walks on all fours. One can note that Raj in Helium is another stunted narrator – stunted not physically, but emotionally – and the best passages here are the ones where we sense the fragility of his hold over past and present, his fear that paranoia and guilt may have unbalanced his perceptions. The writing often has a breathless, quivering vulnerability, as if Raj is using a rush of words to mask his own uncertainties; the narrative is swamped in excessive detail, often provided in parentheses (such as a note about Raj’s sleeping habits and the colour of the kurta-pyjamas he has just been given to wear), which can become annoying if you take it at face value, but works if you consider the fevered mental state of this man.

But stimulating as this book is on some levels, I was discomfited by its use of a fictional framework for purposes that seem better left to reportage.

What good literary fiction in this genre can do is to show us, in abstract terms, how tragedies may occur through a confluence of character, circumstance and history. The emphasis is on uncovering poetic truths about people and situations, as distinct from investigative journalism, which is built on hard facts and explicitly sets out to name real names and ensure that justice is carried out. Helium blurs this distinction. It begins as a moving portrait of a man crippled by guilt (personal guilt as well as guilt by association – on behalf of his father, the hardliners in his community and ultimately even his country) but soon becomes a much more specific harangue against the Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi family. Using real people in a fictional narrative is not in itself a problem – Hanif’s novel, for instance, has brilliant comic passages such as the one where Zia ul Haq goes out into the streets in disguise at night – but Helium does this in a ham-fisted way that takes the reader right out of the story.

What good literary fiction in this genre can do is to show us, in abstract terms, how tragedies may occur through a confluence of character, circumstance and history. The emphasis is on uncovering poetic truths about people and situations, as distinct from investigative journalism, which is built on hard facts and explicitly sets out to name real names and ensure that justice is carried out. Helium blurs this distinction. It begins as a moving portrait of a man crippled by guilt (personal guilt as well as guilt by association – on behalf of his father, the hardliners in his community and ultimately even his country) but soon becomes a much more specific harangue against the Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi family. Using real people in a fictional narrative is not in itself a problem – Hanif’s novel, for instance, has brilliant comic passages such as the one where Zia ul Haq goes out into the streets in disguise at night – but Helium does this in a ham-fisted way that takes the reader right out of the story.

For instance, one important passage where Raj meets a Mr Gopal, an estranged friend of his father, who launches into a monologue about the political cover-up behind the riots, doesn’t read as something that flows organically from the narrative: instead the book grinds to a halt as Gopal Uncle lists the tyrannies of the Indira Gandhi government and the specifics of the riots, spits out phrases like “that failed aeronautical engineer Rajiv Gandhi (Mr Clean)...” and supplies pedantic commentary on the state of the nation in general (“We Indians call ourselves spiritual but we never give away a single rupee. We produce Tatas and Mittals and Ambanis and polyester princes and mining millionaires – while 500 million lead lives more impoverished than the most wretched in Africa”).

The point is not whether this is true (much of it is), or whether fictional characters should be allowed to express their own strident views (of course they should), but that Helium becomes less effective as a novel – as an exploration of Raj's interior life and his attempts at catharsis – at precisely the points where it makes these clumsy, long-winded detours into verisimilitude. It turns to documentation, narrating stories about real people such as the ministers Lalit Maken and H K L Bhagat (The same Congress leader, H K L Bhagat, who, according to witnesses, had ordered his men to kill thousands of Sikhs and rape the women, was now there in the camp distributing blankets and food […] I am unable to forget the face of that monster H K L Bhagat. Member of Parliament. Cabinet Minister. Ex-Mayor of Delhi), and introduces characters who aren’t so much properly realised people as obvious mouthpieces for the author. Watching this novel lose focus and direction is a lesson for writers attempting similar ventures, and a demonstration that well-intentioned lectures don’t usually leave much space for good storytelling.

P.S.I was unsurprised to read a laudatory international review that says:

Being all of seven when the anti-Sikh riots following Indira Gandhi’s assassination took place, I don’t have vivid memories of the time, apart from knowing that my grandfather had to remove the “Singh” nameplate from outside our south Delhi residence. That must have been distressing enough for a proud man who had retired as a Brigadier in the Seventies, but it doesn’t compare to the horrors visited on other, less privileged – or less lucky – members of the community during those lawless days.

The writer Jaspreet Singh must have had a more immediate relationship with the tragedy: it is evident on nearly every angry, mournful page of his new novel

Helium

, written in the voice of a Hindu man returning to India after 25 years in the US. That quarter-century is a form of self-banishment: as a 19-year-old student in 1984, Raj witnessed the killing of his Sikh professor and later realised that his own father – a senior police officer – was complicit in the riots. But an even more complex guilt, rooted in Raj’s relationship with his professor’s attractive wife, may be at play. Now, decades later, he has returned to make sense of the past and possibly slay some of his demons. This is promising material for a novel, but Heliumtries to be too many things at once, which could be a pitfall inherent in its genre.

The writer Jaspreet Singh must have had a more immediate relationship with the tragedy: it is evident on nearly every angry, mournful page of his new novel

Helium

, written in the voice of a Hindu man returning to India after 25 years in the US. That quarter-century is a form of self-banishment: as a 19-year-old student in 1984, Raj witnessed the killing of his Sikh professor and later realised that his own father – a senior police officer – was complicit in the riots. But an even more complex guilt, rooted in Raj’s relationship with his professor’s attractive wife, may be at play. Now, decades later, he has returned to make sense of the past and possibly slay some of his demons. This is promising material for a novel, but Heliumtries to be too many things at once, which could be a pitfall inherent in its genre.When fiction takes on real-world tragedies – especially manmade tragedies that are still fresh in the collective memory – it often happens that the grotesqueness of actual events becomes overwhelming; reality threatens to dwarf the novelist’s imaginative skills. This may be why so much writing of this sort moves beyond realist storytelling and employs surrealism, magic realism or jet-black humour: consider Mohammed Hanif’s A Case Of Exploding Mangoes , a dark satire about the twilight days of the Pakistani dictator Zia ul Haq, or Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat , about another real-life tyrant, the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo, or Raj Kamal Jha’s ambitious but overwritten Fireproof , which approaches the 2002 Gujarat riots tangentially, using the metaphor of a father saddled with a deformed baby on the day after the Godhra killings. By being deliberately over the top, such books often provide a buffer for the reader, shielding us from the full-on assaults of hard reality. But it goes without saying that such flourishes are inherently risky things – very few writers can pull them off with consistent success.

Heliummakes some intriguing stylistic choices too. Singh – who has studied chemical engineering – is deeply influenced by

The Periodic Table

, Primo Levi’s memoir about working as a chemist in fascist Germany: that book is an acknowledged guiding light for him, as he contrasts the shape and movements of chemical elements with the colliding paths and destinies of human beings. But the spirit of another major writer also inhabits these pages. Like W G Sebald, Singh is interested in the variability and unreliability of memory, and collective forgetfulness when it comes to human tragedies; like Sebald, he uses the method of interspersing text with black-and-white images, which testify to the inadequacy of mere writing when it comes to remembering. (Unlike Sebald, he links rheology – the study of the flow of matter – with the viscosity of memories, a natural enough association given Raj's profession and educational background.)

Heliummakes some intriguing stylistic choices too. Singh – who has studied chemical engineering – is deeply influenced by

The Periodic Table

, Primo Levi’s memoir about working as a chemist in fascist Germany: that book is an acknowledged guiding light for him, as he contrasts the shape and movements of chemical elements with the colliding paths and destinies of human beings. But the spirit of another major writer also inhabits these pages. Like W G Sebald, Singh is interested in the variability and unreliability of memory, and collective forgetfulness when it comes to human tragedies; like Sebald, he uses the method of interspersing text with black-and-white images, which testify to the inadequacy of mere writing when it comes to remembering. (Unlike Sebald, he links rheology – the study of the flow of matter – with the viscosity of memories, a natural enough association given Raj's profession and educational background.)Reading Helium, I was also reminded of Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People, a fictionalised account of the aftermath of the Bhopal gas tragedy. Sinha’s novel, which begins with the words “I used to be human once”, is narrated by a misshapen youngster called Jaanvar because he walks on all fours. One can note that Raj in Helium is another stunted narrator – stunted not physically, but emotionally – and the best passages here are the ones where we sense the fragility of his hold over past and present, his fear that paranoia and guilt may have unbalanced his perceptions. The writing often has a breathless, quivering vulnerability, as if Raj is using a rush of words to mask his own uncertainties; the narrative is swamped in excessive detail, often provided in parentheses (such as a note about Raj’s sleeping habits and the colour of the kurta-pyjamas he has just been given to wear), which can become annoying if you take it at face value, but works if you consider the fevered mental state of this man.

But stimulating as this book is on some levels, I was discomfited by its use of a fictional framework for purposes that seem better left to reportage.

What good literary fiction in this genre can do is to show us, in abstract terms, how tragedies may occur through a confluence of character, circumstance and history. The emphasis is on uncovering poetic truths about people and situations, as distinct from investigative journalism, which is built on hard facts and explicitly sets out to name real names and ensure that justice is carried out. Helium blurs this distinction. It begins as a moving portrait of a man crippled by guilt (personal guilt as well as guilt by association – on behalf of his father, the hardliners in his community and ultimately even his country) but soon becomes a much more specific harangue against the Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi family. Using real people in a fictional narrative is not in itself a problem – Hanif’s novel, for instance, has brilliant comic passages such as the one where Zia ul Haq goes out into the streets in disguise at night – but Helium does this in a ham-fisted way that takes the reader right out of the story.

What good literary fiction in this genre can do is to show us, in abstract terms, how tragedies may occur through a confluence of character, circumstance and history. The emphasis is on uncovering poetic truths about people and situations, as distinct from investigative journalism, which is built on hard facts and explicitly sets out to name real names and ensure that justice is carried out. Helium blurs this distinction. It begins as a moving portrait of a man crippled by guilt (personal guilt as well as guilt by association – on behalf of his father, the hardliners in his community and ultimately even his country) but soon becomes a much more specific harangue against the Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi family. Using real people in a fictional narrative is not in itself a problem – Hanif’s novel, for instance, has brilliant comic passages such as the one where Zia ul Haq goes out into the streets in disguise at night – but Helium does this in a ham-fisted way that takes the reader right out of the story.For instance, one important passage where Raj meets a Mr Gopal, an estranged friend of his father, who launches into a monologue about the political cover-up behind the riots, doesn’t read as something that flows organically from the narrative: instead the book grinds to a halt as Gopal Uncle lists the tyrannies of the Indira Gandhi government and the specifics of the riots, spits out phrases like “that failed aeronautical engineer Rajiv Gandhi (Mr Clean)...” and supplies pedantic commentary on the state of the nation in general (“We Indians call ourselves spiritual but we never give away a single rupee. We produce Tatas and Mittals and Ambanis and polyester princes and mining millionaires – while 500 million lead lives more impoverished than the most wretched in Africa”).

The point is not whether this is true (much of it is), or whether fictional characters should be allowed to express their own strident views (of course they should), but that Helium becomes less effective as a novel – as an exploration of Raj's interior life and his attempts at catharsis – at precisely the points where it makes these clumsy, long-winded detours into verisimilitude. It turns to documentation, narrating stories about real people such as the ministers Lalit Maken and H K L Bhagat (The same Congress leader, H K L Bhagat, who, according to witnesses, had ordered his men to kill thousands of Sikhs and rape the women, was now there in the camp distributing blankets and food […] I am unable to forget the face of that monster H K L Bhagat. Member of Parliament. Cabinet Minister. Ex-Mayor of Delhi), and introduces characters who aren’t so much properly realised people as obvious mouthpieces for the author. Watching this novel lose focus and direction is a lesson for writers attempting similar ventures, and a demonstration that well-intentioned lectures don’t usually leave much space for good storytelling.

P.S.I was unsurprised to read a laudatory international review that says:

The novel argues that such acts of violence were not spontaneous, not simply bloody revenge for the killing of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards; the novel states that the killers were actively encouraged and orchestrated by well-known government officials and condoned by the police and authorities who, over a course of days, allowed mobs to maim and kill (blood for blood, the murderers cried).This makes it sound like Helium is uncovering things that have not before been brought into public discourse, which is far from the case; but even so, are these adequate grounds for endorsement? The suggestion that this novel's worth lies in its “controversial” or "revealing" take on an important real-life tragedy amounts to elevating intention over execution, while neglecting the unevenness of its tone, the meandering floridity of its prose (“I sketch birds,” I lied. “What kind?” “The ones that live inside me. I need to draw every day. My daily exorcisms.” “You appear to be an intense man”) and, of course, the heavy-handedness of its pamphleteering.

Published on December 10, 2013 18:08

December 5, 2013

Lingua fracas in Nayakan and Inglourious Basterds: movie characters confounded by language

One of last year's most popular feel-good films was Gauri Shinde’s

English Vinglish

, with Sridevi as a diffident, middle-aged woman visiting America and barely knowing how to get by, given her limited knowledge of English. On arriving in New York, she is beset – both on the streets and in her sister’s house – by words spoken in incomprehensible accents, and generally disoriented by the pace of life around her. At one point the film’s music track expresses her state of mind through a melange of sounds coming at her from all directions; meanwhile the title song gently combines English with Hindi in ways that are familiar to most middle-class Indians. (“Badlaa nazaraa yun yun yun / Saara ka saara new new new.”)

One of last year's most popular feel-good films was Gauri Shinde’s

English Vinglish

, with Sridevi as a diffident, middle-aged woman visiting America and barely knowing how to get by, given her limited knowledge of English. On arriving in New York, she is beset – both on the streets and in her sister’s house – by words spoken in incomprehensible accents, and generally disoriented by the pace of life around her. At one point the film’s music track expresses her state of mind through a melange of sounds coming at her from all directions; meanwhile the title song gently combines English with Hindi in ways that are familiar to most middle-class Indians. (“Badlaa nazaraa yun yun yun / Saara ka saara new new new.”)I thought about the hegemony of language again recently while watching scenes in two very different films, scenes that showed how fluency or lack of fluency in a language can affect our perceptions of people: the powerful can seem like underdogs, good guys may appear ridiculous, bad guys almost admirable. The first was Mani Rathnam’s 1987 classic Nayakan , fuelled by Kamal Haasan’s stunning performance as Velu Nayakan, who becomes an underworld don and a godfather to the South Indian community in Bombay. I had an strange moment watching Nayakan: having become immersed in the story, and taken its “Tamil-ness” for granted (this was a clearly South Indian film, I had to read subtitles to understand it), I temporarily forgot that the setting was Bombay, and that people outside Velu’s immediate, enclosed environment speak in Hindi or Marathi.

This came home in a scene where Velu – already a well-respected don – has to interact with dons from other parts of the city. Suddenly traces of uncertainty, wariness, even vulnerability, appear on his face as he tries to size up these potential rivals or enemies, whose speech he can’t easily follow. As viewers, we have been thinking of Velu as a larger-than-life figure, firmly in control of his fiefdom, but now we see him in more human terms. There is also something moving about the suggestion that Velu, despite spending almost his entire life in Bombay, never properly learns the city’s majority languages – this gives his situation a nuance that differentiates it from the story of the young Vito Corleone in Little Italy in The Godfather Part II (a film that Nayakan has clear links with), slowly picking up English as he makes his way in the world, so that the transition from the Italian-speaking Vito (played by Robert de Niro) to the English-mumbling patriarch (Marlon Brando) seems wholly natural. Nayakan, on the other hand, gets much of its edge from Velu’s immutable foreignness. No wonder Mani Rathnam expressed dissatisfaction (in one of his interviews with Baradwaj Rangan) with the Hindi remake of the film, Feroz Khan’s Dayavan: the remake was about a Mumbaikar in Mumbai, where he is culturally and linguistically at home, which meant an important subtext about alienation was absent.

This came home in a scene where Velu – already a well-respected don – has to interact with dons from other parts of the city. Suddenly traces of uncertainty, wariness, even vulnerability, appear on his face as he tries to size up these potential rivals or enemies, whose speech he can’t easily follow. As viewers, we have been thinking of Velu as a larger-than-life figure, firmly in control of his fiefdom, but now we see him in more human terms. There is also something moving about the suggestion that Velu, despite spending almost his entire life in Bombay, never properly learns the city’s majority languages – this gives his situation a nuance that differentiates it from the story of the young Vito Corleone in Little Italy in The Godfather Part II (a film that Nayakan has clear links with), slowly picking up English as he makes his way in the world, so that the transition from the Italian-speaking Vito (played by Robert de Niro) to the English-mumbling patriarch (Marlon Brando) seems wholly natural. Nayakan, on the other hand, gets much of its edge from Velu’s immutable foreignness. No wonder Mani Rathnam expressed dissatisfaction (in one of his interviews with Baradwaj Rangan) with the Hindi remake of the film, Feroz Khan’s Dayavan: the remake was about a Mumbaikar in Mumbai, where he is culturally and linguistically at home, which meant an important subtext about alienation was absent.

****

The other scene is a comic one, but provides food for thought too. It is from Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds , a wish-fulfilling alternate history in which Nazi hunters save the day during World War II. The villain here is Hans Landa, played by Christoph Waltz: he is terrifyingly smooth, sharp... and a polyglot, which gives him an edge over the good guys, the “Basterds” led by Aldo (Brad Pitt), all of whom are barely fluent in one language, English (more accurately American, spoken in a distinct Southern drawl). One of the film’s funniest scenes has Aldo and team disguised as Italians at a party, while Landa – well aware that they are imposters – toys with them like a cat slowly prying open a box of inauthentic but tasty pasta. (Earlier, when we heard Brad Pitt say “I can speak some Aye-talian” - in response to his German informer contemptuously asking if they know any language other than English - we could tell these boys would soon be treading on thin ice. And so it comes to pass.)

It’s an excellent comic premise, one that combines tension with laughs, and also invites the viewer to consider his own responses to the characters. Here are Aldo and company trying to save the world by infiltrating the dens of the Nazi top brass, and yet they barely understand a word of German. We are supposed to be rooting for them, but they look and behave like hicks – the Three Stooges handed a World War and unsure what to do with it – confirming every stereotype of the insular, ignorant American; in comparison the nasty Landa seems like a higher, more cultured species. We cringe when Aldo says “Bonjourno”, enunciating the word much too deliberately. Then we chuckle when Landa (who seems able to toss off any language as if he were born speaking it) turns out to be a fluent Italian speaker too, and when he deferentially asks the “Italians” if hispronunciation is right. (“Si si, correcto,” Aldo replies, before grunting “Arrividerci” - or "A river derchy" - in a ludicrously fake accent.)

It’s an excellent comic premise, one that combines tension with laughs, and also invites the viewer to consider his own responses to the characters. Here are Aldo and company trying to save the world by infiltrating the dens of the Nazi top brass, and yet they barely understand a word of German. We are supposed to be rooting for them, but they look and behave like hicks – the Three Stooges handed a World War and unsure what to do with it – confirming every stereotype of the insular, ignorant American; in comparison the nasty Landa seems like a higher, more cultured species. We cringe when Aldo says “Bonjourno”, enunciating the word much too deliberately. Then we chuckle when Landa (who seems able to toss off any language as if he were born speaking it) turns out to be a fluent Italian speaker too, and when he deferentially asks the “Italians” if hispronunciation is right. (“Si si, correcto,” Aldo replies, before grunting “Arrividerci” - or "A river derchy" - in a ludicrously fake accent.)Almost in spite of their tomfoolery here, the good guys do eventually get the job done. But when Aldo gets the better of Landa in the film’s last scene, he does it not by winning a verbal duel but by using a knife to carve an incriminating swastika on his adversary’s forehead. The caveman comes out on top because he knows how to use crude tools – and speech be damned.

[Did a version of this for Business Standard. An earlier post here on Tarantino's Django Unchained, in which Christoph Waltz plays another character who uses language so fluidly that everyone around him looks like they've just stumbled in from the Paleolithic]

Published on December 05, 2013 18:00

December 4, 2013

All aboard the Matinee Express (Gaadi bula rahi hai)

[A vignette-ish piece I did for The Indian Quarterly, about train scenes in Indian cinema. Many more films and sequences could have been mentioned, of course - feel free to add to the list]

---------------------

One of the earliest "movies" to be screened – perhaps the most famous of its time – was a 50-second record of a train pulling into a station: the Lumière Brothers’ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station , made in 1895. There is something oddly apt about this early union of locomotive and celluloid, for trains represent movement, and movement was also the unique selling point of those mystical things called motion pictures, which began to haunt people’s dreams towards the end of the 19th century.

No wonder there is a widely told story about viewers leaping out of their seats in terror as the Lumières’ train seemed to head towards them. The story may be exaggerated, but it sounds like it should be true: as a famous linein an American Western (a movie genre that would make significant use of the railroad) put it, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” So let us propose that that train was the first ever movie monster (dare one say “bogie-man”?) – predating filmic depictions of literary characters like Dracula or Frankenstein or Mr Hyde, not to mention the thousands of monsters that were first dreamt up for cinema.