Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 70

February 11, 2014

United we shoot - quotes from a few good men in movies

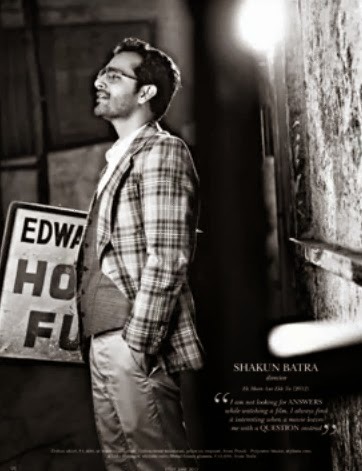

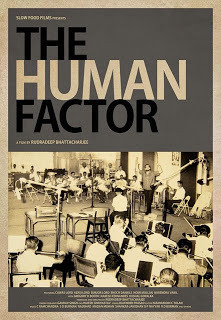

[This is a piece I did for Elle magazine last year. It was done to a clearly specified brief: here’s a list of eight men who are doing interesting, behind-the-scenes work in Hindi cinema, and whom we have gathered for a photo shoot; speak to them and weave their quotes into an essay. As such, it wasn’t much of a challenge writing-wise – apart from the fact that there were a disproportionate number of cinematographers in the list, which made it tricky to divided up the quotes – but the conversations were nice. I have other bytes that I hope to use in a column sometime]

“There is usually a sound in my head when I am writing a scene,” says director

“There is usually a sound in my head when I am writing a scene,” says director

It also suggests a couple of things about contemporary movie-making: that a director with a strong vision can bring his stamp to every aspect of the process (“My films must have me in them,” Nambiar says, “they have to be expressions of my personal tastes and interests”), and that there is a greater willingness to experiment, to do things that would once have been considered very radical. Music producer and composer Mikey McCleary , who reworked “Khoya Khoya Chand”, points out that filmmakers are no longer hung up on having a single composer doing the music for their movies, and that they often choose pre-existing tunes from the independent scene, rather than commissioning scores from a familiar set of insiders. “This brings in more variety and opens up fresh possibilities for a film.”

More generally too, today’s Hindi cinema has shown a willingness to step outside traditional comfort zones. Thanks to a combination of the Internet, the DVD culture and greater dissemination of information, a generation of young writers and directors have been absorbing the best of other cinemas and bringing their own sensibilities to them. There are offbeat stories, newer settings, more realism in language, and greater emphasis on background detailing and production design – things that are vital for capturing a sense of place and time. The industry’s newfound confidence about being part of a larger filmic universe is also reflected in the growing participation of non-Indians – such as McCleary or the cinematographers

“Earlier, our films were largely about escapism, such as showing Switzerland to an audience who would never go there,” lensman Kartik Vijay points out, “but today directors are making films about things they have firsthand experience of.” Naturally, to realise their visions, these directors need high standards of craftsmanship in every field. Speaking with some of our leading technicians, one is reminded that the best films represent a smooth synthesis of different elements, aimed at maintaining the reality of the world depicted in the movie. Vijay – who has worked with such major directors as Vishal Bhardwaj and Dibakar Banerjee – relates how he used bright colours to capture the vibrancy of the West Delhi Punjabi culture in Banerjee’s Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, and how subtle alterations in lighting can signal a narrative shift from a warm, happy mood to something more hard-edged. For Bhardwaj’s

Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola

, he tried to reflect the character Mandola’s darker shades by gradually letting the colours go out as the story progresses. While shooting Banerjee’s Shanghai, the Greek-born Andritzakis converted his first-time impressions (as a foreigner) of Mumbai busy street-life into images that matched the grim mood of the story, and also worked closely with the art designers to get the right look. McCleary, who did the soundtrack for the same film, embellished the sound of Mumbai street-drums with dark, ambient music to achieve an effect that would be familiar and sinister at the same time.

For Bhardwaj’s

Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola

, he tried to reflect the character Mandola’s darker shades by gradually letting the colours go out as the story progresses. While shooting Banerjee’s Shanghai, the Greek-born Andritzakis converted his first-time impressions (as a foreigner) of Mumbai busy street-life into images that matched the grim mood of the story, and also worked closely with the art designers to get the right look. McCleary, who did the soundtrack for the same film, embellished the sound of Mumbai street-drums with dark, ambient music to achieve an effect that would be familiar and sinister at the same time.

“The entire team needs to work in tandem from the very beginning – you can’t have a situation where two departments don’t know what the other is doing,” says costume designer

Those of us on the outside make simple distinctions between “commercial” and “art” cinema, or grumble that financial considerations always undermine artistic integrity, but things aren’t so cut-and-dried – big production houses are more open to fresh, edgy films. Director

But as Andritzakis points out, even mainstream films are becoming better crafted, and there is less self-consciousness now about categories. Cinematographer

Ayananka Bose

, who has worked on a number of very high-profile, big-budget movies, says every film presents its own special challenge: for instance, Jhoom Barabar Jhoom required a flamboyant, colourful, big-musical feel, but Kites had to be suffused with the heat of the desert and the Las Vegas setting. “I don’t think much about the ‘big-budget’ or ‘glamorous’ tags,” he says, “What matters is quality of execution. The camera is the same, the lens is the same – you are in control of your craft.”

But as Andritzakis points out, even mainstream films are becoming better crafted, and there is less self-consciousness now about categories. Cinematographer

Ayananka Bose

, who has worked on a number of very high-profile, big-budget movies, says every film presents its own special challenge: for instance, Jhoom Barabar Jhoom required a flamboyant, colourful, big-musical feel, but Kites had to be suffused with the heat of the desert and the Las Vegas setting. “I don’t think much about the ‘big-budget’ or ‘glamorous’ tags,” he says, “What matters is quality of execution. The camera is the same, the lens is the same – you are in control of your craft.”

Speaking of which, changes in technology have been levelling the playing field and making filmmaking much more democratic than it once was. “Technology has put a movie camera in the hands of anyone who has a smart-phone,” says Vijay, and this means young talents have an early outlet for their imagination. Simultaneously, social media has made filmmakers more accessible: Nambiar speaks of musicians sending him their tunes online, which he can listen to instantly. Naturally this can cause clutter, but the best work does tend to stand out; as Bose points out, ultimately, the mind behind the equipment is what matters. “You can always identify someone who is a pseudo-intellectual imitator of Godard or Truffaut vs someone who has originality.”

Communication can flow in the opposite direction too. There have been cases of directors and writers getting their films financed by reaching out to like-minded people on Facebook or Twitter: one such film, Onir’s I Am, even went on to win a National Award. Meanwhile, viewers too are more aware and sophisticated than before, which means they are open to new forms and idioms. “Audiences are exposed to more, and willing to accept more,” Rawal says, “Animation for grown-ups is a field that I am very excited about – I think Indian cinema is going to go places in it.”

What all this adds up to is a scenario where people with a passion for cinema are pulling each other up, showing a collaborative generosity that represents the opposite of the crabs-in- a-well mentality. It comes out of a genuine sense that everyone can be part of the change. No wonder the enthusiastic statements made by these young talents don’t seem glib or facile. When Batra says “It is the beginning of a golden age in Hindi cinema”, or Andritzakis says “I’m very lucky to have arrived at a time when things are starting to explode”, it sounds like an accurate response to working in an increasingly vibrant industry. “Every time I am at a film festival,” says Carlos Catalan, “I realise that there is a talented wave of Indian directors telling different stories in different ways. World audiences are hungry to watch those films.” With these good men working away behind the scenes, that appetite should increase.

What all this adds up to is a scenario where people with a passion for cinema are pulling each other up, showing a collaborative generosity that represents the opposite of the crabs-in- a-well mentality. It comes out of a genuine sense that everyone can be part of the change. No wonder the enthusiastic statements made by these young talents don’t seem glib or facile. When Batra says “It is the beginning of a golden age in Hindi cinema”, or Andritzakis says “I’m very lucky to have arrived at a time when things are starting to explode”, it sounds like an accurate response to working in an increasingly vibrant industry. “Every time I am at a film festival,” says Carlos Catalan, “I realise that there is a talented wave of Indian directors telling different stories in different ways. World audiences are hungry to watch those films.” With these good men working away behind the scenes, that appetite should increase.

[A related piece: short profiles of 10 trailblazers of the new Indian cinema, across categories]

“There is usually a sound in my head when I am writing a scene,” says director

“There is usually a sound in my head when I am writing a scene,” says director It also suggests a couple of things about contemporary movie-making: that a director with a strong vision can bring his stamp to every aspect of the process (“My films must have me in them,” Nambiar says, “they have to be expressions of my personal tastes and interests”), and that there is a greater willingness to experiment, to do things that would once have been considered very radical. Music producer and composer Mikey McCleary , who reworked “Khoya Khoya Chand”, points out that filmmakers are no longer hung up on having a single composer doing the music for their movies, and that they often choose pre-existing tunes from the independent scene, rather than commissioning scores from a familiar set of insiders. “This brings in more variety and opens up fresh possibilities for a film.”

More generally too, today’s Hindi cinema has shown a willingness to step outside traditional comfort zones. Thanks to a combination of the Internet, the DVD culture and greater dissemination of information, a generation of young writers and directors have been absorbing the best of other cinemas and bringing their own sensibilities to them. There are offbeat stories, newer settings, more realism in language, and greater emphasis on background detailing and production design – things that are vital for capturing a sense of place and time. The industry’s newfound confidence about being part of a larger filmic universe is also reflected in the growing participation of non-Indians – such as McCleary or the cinematographers

“Earlier, our films were largely about escapism, such as showing Switzerland to an audience who would never go there,” lensman Kartik Vijay points out, “but today directors are making films about things they have firsthand experience of.” Naturally, to realise their visions, these directors need high standards of craftsmanship in every field. Speaking with some of our leading technicians, one is reminded that the best films represent a smooth synthesis of different elements, aimed at maintaining the reality of the world depicted in the movie. Vijay – who has worked with such major directors as Vishal Bhardwaj and Dibakar Banerjee – relates how he used bright colours to capture the vibrancy of the West Delhi Punjabi culture in Banerjee’s Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, and how subtle alterations in lighting can signal a narrative shift from a warm, happy mood to something more hard-edged.

For Bhardwaj’s

Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola

, he tried to reflect the character Mandola’s darker shades by gradually letting the colours go out as the story progresses. While shooting Banerjee’s Shanghai, the Greek-born Andritzakis converted his first-time impressions (as a foreigner) of Mumbai busy street-life into images that matched the grim mood of the story, and also worked closely with the art designers to get the right look. McCleary, who did the soundtrack for the same film, embellished the sound of Mumbai street-drums with dark, ambient music to achieve an effect that would be familiar and sinister at the same time.

For Bhardwaj’s

Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola

, he tried to reflect the character Mandola’s darker shades by gradually letting the colours go out as the story progresses. While shooting Banerjee’s Shanghai, the Greek-born Andritzakis converted his first-time impressions (as a foreigner) of Mumbai busy street-life into images that matched the grim mood of the story, and also worked closely with the art designers to get the right look. McCleary, who did the soundtrack for the same film, embellished the sound of Mumbai street-drums with dark, ambient music to achieve an effect that would be familiar and sinister at the same time.“The entire team needs to work in tandem from the very beginning – you can’t have a situation where two departments don’t know what the other is doing,” says costume designer

Those of us on the outside make simple distinctions between “commercial” and “art” cinema, or grumble that financial considerations always undermine artistic integrity, but things aren’t so cut-and-dried – big production houses are more open to fresh, edgy films. Director

But as Andritzakis points out, even mainstream films are becoming better crafted, and there is less self-consciousness now about categories. Cinematographer

Ayananka Bose

, who has worked on a number of very high-profile, big-budget movies, says every film presents its own special challenge: for instance, Jhoom Barabar Jhoom required a flamboyant, colourful, big-musical feel, but Kites had to be suffused with the heat of the desert and the Las Vegas setting. “I don’t think much about the ‘big-budget’ or ‘glamorous’ tags,” he says, “What matters is quality of execution. The camera is the same, the lens is the same – you are in control of your craft.”

But as Andritzakis points out, even mainstream films are becoming better crafted, and there is less self-consciousness now about categories. Cinematographer

Ayananka Bose

, who has worked on a number of very high-profile, big-budget movies, says every film presents its own special challenge: for instance, Jhoom Barabar Jhoom required a flamboyant, colourful, big-musical feel, but Kites had to be suffused with the heat of the desert and the Las Vegas setting. “I don’t think much about the ‘big-budget’ or ‘glamorous’ tags,” he says, “What matters is quality of execution. The camera is the same, the lens is the same – you are in control of your craft.”Speaking of which, changes in technology have been levelling the playing field and making filmmaking much more democratic than it once was. “Technology has put a movie camera in the hands of anyone who has a smart-phone,” says Vijay, and this means young talents have an early outlet for their imagination. Simultaneously, social media has made filmmakers more accessible: Nambiar speaks of musicians sending him their tunes online, which he can listen to instantly. Naturally this can cause clutter, but the best work does tend to stand out; as Bose points out, ultimately, the mind behind the equipment is what matters. “You can always identify someone who is a pseudo-intellectual imitator of Godard or Truffaut vs someone who has originality.”

Communication can flow in the opposite direction too. There have been cases of directors and writers getting their films financed by reaching out to like-minded people on Facebook or Twitter: one such film, Onir’s I Am, even went on to win a National Award. Meanwhile, viewers too are more aware and sophisticated than before, which means they are open to new forms and idioms. “Audiences are exposed to more, and willing to accept more,” Rawal says, “Animation for grown-ups is a field that I am very excited about – I think Indian cinema is going to go places in it.”

What all this adds up to is a scenario where people with a passion for cinema are pulling each other up, showing a collaborative generosity that represents the opposite of the crabs-in- a-well mentality. It comes out of a genuine sense that everyone can be part of the change. No wonder the enthusiastic statements made by these young talents don’t seem glib or facile. When Batra says “It is the beginning of a golden age in Hindi cinema”, or Andritzakis says “I’m very lucky to have arrived at a time when things are starting to explode”, it sounds like an accurate response to working in an increasingly vibrant industry. “Every time I am at a film festival,” says Carlos Catalan, “I realise that there is a talented wave of Indian directors telling different stories in different ways. World audiences are hungry to watch those films.” With these good men working away behind the scenes, that appetite should increase.

What all this adds up to is a scenario where people with a passion for cinema are pulling each other up, showing a collaborative generosity that represents the opposite of the crabs-in- a-well mentality. It comes out of a genuine sense that everyone can be part of the change. No wonder the enthusiastic statements made by these young talents don’t seem glib or facile. When Batra says “It is the beginning of a golden age in Hindi cinema”, or Andritzakis says “I’m very lucky to have arrived at a time when things are starting to explode”, it sounds like an accurate response to working in an increasingly vibrant industry. “Every time I am at a film festival,” says Carlos Catalan, “I realise that there is a talented wave of Indian directors telling different stories in different ways. World audiences are hungry to watch those films.” With these good men working away behind the scenes, that appetite should increase.[A related piece: short profiles of 10 trailblazers of the new Indian cinema, across categories]

Published on February 11, 2014 01:42

February 7, 2014

Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! – the town boy, the city and a pyramid of gags

When I interviewed writer-director Kundan Shah for the Jaane bhi do Yaaro book a few years ago, he mentioned learning one of the principles of movie comedy while watching silent films at the FTII – how to “build a gag on a gag on a gag on a gag on a gag on a gag until you have a pyramid of gags”. Watching the 1923 Harold Lloyd-starrer

Safety Last!

(on a newly acquired Criterion disc-set), I thought again of those words. The film, with its multiple gag-pyramids – which add up to form one giant pyramid – is testament to how much thought, effort and practice can go into little moments that achieve nothing more “consequential” than making people laugh, or gape, or do both things at the same time.

I came to Safety Last! much later than I should have, but like so many others who haven’t seen the film I knew it by its most famous image: the scene where Lloyd (playing his stock character, the bespectacled everyman known here as The Boy as well as Harold) hangs for dear life from the face of a building clock. That scene is a cornerstone of the film’s biggest “pyramid” – circumstances having forced the hapless Harold to climb a 12-storey building for a publicity stunt – but there is so much more to Safety Last!. Watching it was a reminder that good silent-film comedy – with its sight gags, set-ups, incredible feats of timing, balletic physical movements, and minimal reliance on inter-titles – was one of the purest expressions of “pure cinema”. And that Keaton and Chaplin weren’t the only masters of those underrated arts.

I came to Safety Last! much later than I should have, but like so many others who haven’t seen the film I knew it by its most famous image: the scene where Lloyd (playing his stock character, the bespectacled everyman known here as The Boy as well as Harold) hangs for dear life from the face of a building clock. That scene is a cornerstone of the film’s biggest “pyramid” – circumstances having forced the hapless Harold to climb a 12-storey building for a publicity stunt – but there is so much more to Safety Last!. Watching it was a reminder that good silent-film comedy – with its sight gags, set-ups, incredible feats of timing, balletic physical movements, and minimal reliance on inter-titles – was one of the purest expressions of “pure cinema”. And that Keaton and Chaplin weren’t the only masters of those underrated arts.

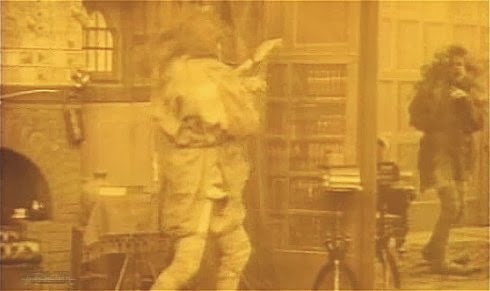

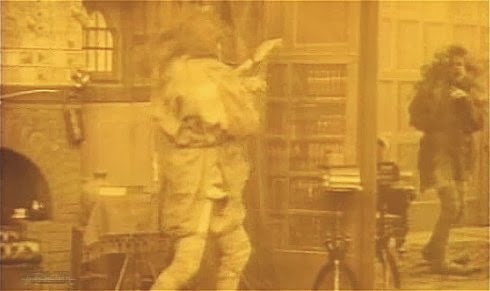

In the best cases, even the inter-titles (which performed a functional role in most silent movies) would be used to clever effect. Consider the grim one that opens this film, and the shot that immediately follows it:

The camera then draws back to show two weeping women – the Boy’s mother and girlfriend – on the other side of the bars. A policeman and a priest enter the frame too, and the meaning of the scene appears clear from these elements – but of course it’s a set-up, the first of many fine sight gags: it turns out that they are all at the railway station, the “hangman’s noose” is really a loop used to attach mail for passing trains to pick up, and the Boy is only going to the big city for a job.

Once this has been revealed, it would be understandable if the film slowed down for a bit to establish the situation and the characters. Yet, after only a brief interlude – where Harold and his girlfriend Mildred (played by Lloyd’s real-life wife Mildred Davis) express their hopes for the future – the gags continue with a seamlessly executed scene where Harold, rushing to catch the train, picks up a pram with a baby in it instead of his suitcase. In itself, this is nothing special – a staple comedy-of-errors scene – but it is the necessary build-up to the final visual gag of this sequence. The baby’s mother catches up with him just as he is about to climb aboard, the mix-up is sorted out, but the distracted Harold doesn’t realise that the train has started moving away. Without looking, he stretches his arm out behind him …and ends up on a passing horse-cart instead. Discovering his mistake, he runs after the train and leaps on, by now a receding figure, but with enough presence of mind left to wave a second cheery goodbye. Fade out.

A description like this is no substitute for watching the two-minute scene play out, of course. It is a marvelous line of comic sketches, building on – and running into – one another: an opening shot that catches us off balance before allowing us a little chuckle of relief, then the mix-up culminating in the agile physical comedy. And in between all this, an important “serious” moment – a close-up of the lovers before they part – that suggests what is at stake for the main character: what the Big City, with its tall buildings, office politics, expensive food, menacing clocks, and rich shoppers bullying overworked salespeople, will mean for him.

then the mix-up culminating in the agile physical comedy. And in between all this, an important “serious” moment – a close-up of the lovers before they part – that suggests what is at stake for the main character: what the Big City, with its tall buildings, office politics, expensive food, menacing clocks, and rich shoppers bullying overworked salespeople, will mean for him.

The film has many more such sequences, leading up to that super finale where Harold climbs the building unaided, in pursuit of a 1000 valuable dollars. This is one of the great ascents in any movie, right up there with King Kong – also a visitor from the boondocks trying to make sense of the city – climbing the Empire State Building 10 years after Safety Last! was made. (Or this opening scene from another great silent film, King Vidor’s The Crowd, where a camera “climbs” a skyscraper.) The gags in this last act literally build as Harold climbs from one floor to the next, facing a new challenge each time. It is heart-in-your-mouth thrilling, but – without detracting from the “fun” – it is also emotionally resonant for anyone who has come to sympathise with the Boy (easy to do; Lloyd is a natural and likable actor). Here is a scene that literalises the idea of the small-town boy as social climber. As critic Leonard Maltin and archivist Richard Correll point out in the Criterion commentary track, not only do the obstacles pile up in the final sequence, they get tougher and more outlandish. (A vagrant badminton net? A mouse running up his pants leg? A photo shoot somewhere on the 10th floor, involving a man with a gun?)

Which means this could be an image of the upwardly mobile professional climbing the ranks in a cutthroat world, with the stakes constantly increasing: the danger of falling and losing everything becomes more pronounced the higher he goes. This lovely, light comedy – while consistently being a lovely, light comedy – is up there with any of the more serious-minded examinations of what can be lost and gained in the move from a “simpler” way of life to a more competitive one; a worthy companion piece to other silent classics of the time like Greed or Sunrise or The Crowd, which offered the big city as a place where you might lose your footing (or your soul).

I watched Safety Last! alone, on DVD, with a prior idea of what the film was about, and I was still deeply stirred by it (the orchestral soundtrack by Carl Davis from 1989 goes very well with the film too) – so I can't imagine what it must have felt like to unprepared audiences in a theatre in the pre-CGI era, people who had never been exposed to such stuntwork in a movie. Even today’s viewers might find their mouths open when a dazed Harold swaggers about on the very edge of the roof after being struck by a weather-vane. No wonder the last shot– with the Boy back on firm ground and in the safety of the Girl’s arms – brings such a sense of release. It is a little like King Kong with a different ending, one where the ape and the blonde are reunited for ever on the rooftop. But is this a happy ending exactly? Even a thousand dollars may not go a very long way, and if the city is going to keep throwing up such challenges perhaps the young man may have been better off with his head in that noose after all.

I watched Safety Last! alone, on DVD, with a prior idea of what the film was about, and I was still deeply stirred by it (the orchestral soundtrack by Carl Davis from 1989 goes very well with the film too) – so I can't imagine what it must have felt like to unprepared audiences in a theatre in the pre-CGI era, people who had never been exposed to such stuntwork in a movie. Even today’s viewers might find their mouths open when a dazed Harold swaggers about on the very edge of the roof after being struck by a weather-vane. No wonder the last shot– with the Boy back on firm ground and in the safety of the Girl’s arms – brings such a sense of release. It is a little like King Kong with a different ending, one where the ape and the blonde are reunited for ever on the rooftop. But is this a happy ending exactly? Even a thousand dollars may not go a very long way, and if the city is going to keep throwing up such challenges perhaps the young man may have been better off with his head in that noose after all.

P.S. two shots from films about a struggler in the city. A tram sequence in Safety Last! with hordes of men clinging to the outside of the vehicle and to each other, like bees to a hive:

And Kishore Kumar on a bus in Naukri 30 years later:

I came to Safety Last! much later than I should have, but like so many others who haven’t seen the film I knew it by its most famous image: the scene where Lloyd (playing his stock character, the bespectacled everyman known here as The Boy as well as Harold) hangs for dear life from the face of a building clock. That scene is a cornerstone of the film’s biggest “pyramid” – circumstances having forced the hapless Harold to climb a 12-storey building for a publicity stunt – but there is so much more to Safety Last!. Watching it was a reminder that good silent-film comedy – with its sight gags, set-ups, incredible feats of timing, balletic physical movements, and minimal reliance on inter-titles – was one of the purest expressions of “pure cinema”. And that Keaton and Chaplin weren’t the only masters of those underrated arts.

I came to Safety Last! much later than I should have, but like so many others who haven’t seen the film I knew it by its most famous image: the scene where Lloyd (playing his stock character, the bespectacled everyman known here as The Boy as well as Harold) hangs for dear life from the face of a building clock. That scene is a cornerstone of the film’s biggest “pyramid” – circumstances having forced the hapless Harold to climb a 12-storey building for a publicity stunt – but there is so much more to Safety Last!. Watching it was a reminder that good silent-film comedy – with its sight gags, set-ups, incredible feats of timing, balletic physical movements, and minimal reliance on inter-titles – was one of the purest expressions of “pure cinema”. And that Keaton and Chaplin weren’t the only masters of those underrated arts.In the best cases, even the inter-titles (which performed a functional role in most silent movies) would be used to clever effect. Consider the grim one that opens this film, and the shot that immediately follows it:

The camera then draws back to show two weeping women – the Boy’s mother and girlfriend – on the other side of the bars. A policeman and a priest enter the frame too, and the meaning of the scene appears clear from these elements – but of course it’s a set-up, the first of many fine sight gags: it turns out that they are all at the railway station, the “hangman’s noose” is really a loop used to attach mail for passing trains to pick up, and the Boy is only going to the big city for a job.

Once this has been revealed, it would be understandable if the film slowed down for a bit to establish the situation and the characters. Yet, after only a brief interlude – where Harold and his girlfriend Mildred (played by Lloyd’s real-life wife Mildred Davis) express their hopes for the future – the gags continue with a seamlessly executed scene where Harold, rushing to catch the train, picks up a pram with a baby in it instead of his suitcase. In itself, this is nothing special – a staple comedy-of-errors scene – but it is the necessary build-up to the final visual gag of this sequence. The baby’s mother catches up with him just as he is about to climb aboard, the mix-up is sorted out, but the distracted Harold doesn’t realise that the train has started moving away. Without looking, he stretches his arm out behind him …and ends up on a passing horse-cart instead. Discovering his mistake, he runs after the train and leaps on, by now a receding figure, but with enough presence of mind left to wave a second cheery goodbye. Fade out.

A description like this is no substitute for watching the two-minute scene play out, of course. It is a marvelous line of comic sketches, building on – and running into – one another: an opening shot that catches us off balance before allowing us a little chuckle of relief,

then the mix-up culminating in the agile physical comedy. And in between all this, an important “serious” moment – a close-up of the lovers before they part – that suggests what is at stake for the main character: what the Big City, with its tall buildings, office politics, expensive food, menacing clocks, and rich shoppers bullying overworked salespeople, will mean for him.

then the mix-up culminating in the agile physical comedy. And in between all this, an important “serious” moment – a close-up of the lovers before they part – that suggests what is at stake for the main character: what the Big City, with its tall buildings, office politics, expensive food, menacing clocks, and rich shoppers bullying overworked salespeople, will mean for him.The film has many more such sequences, leading up to that super finale where Harold climbs the building unaided, in pursuit of a 1000 valuable dollars. This is one of the great ascents in any movie, right up there with King Kong – also a visitor from the boondocks trying to make sense of the city – climbing the Empire State Building 10 years after Safety Last! was made. (Or this opening scene from another great silent film, King Vidor’s The Crowd, where a camera “climbs” a skyscraper.) The gags in this last act literally build as Harold climbs from one floor to the next, facing a new challenge each time. It is heart-in-your-mouth thrilling, but – without detracting from the “fun” – it is also emotionally resonant for anyone who has come to sympathise with the Boy (easy to do; Lloyd is a natural and likable actor). Here is a scene that literalises the idea of the small-town boy as social climber. As critic Leonard Maltin and archivist Richard Correll point out in the Criterion commentary track, not only do the obstacles pile up in the final sequence, they get tougher and more outlandish. (A vagrant badminton net? A mouse running up his pants leg? A photo shoot somewhere on the 10th floor, involving a man with a gun?)

Which means this could be an image of the upwardly mobile professional climbing the ranks in a cutthroat world, with the stakes constantly increasing: the danger of falling and losing everything becomes more pronounced the higher he goes. This lovely, light comedy – while consistently being a lovely, light comedy – is up there with any of the more serious-minded examinations of what can be lost and gained in the move from a “simpler” way of life to a more competitive one; a worthy companion piece to other silent classics of the time like Greed or Sunrise or The Crowd, which offered the big city as a place where you might lose your footing (or your soul).

I watched Safety Last! alone, on DVD, with a prior idea of what the film was about, and I was still deeply stirred by it (the orchestral soundtrack by Carl Davis from 1989 goes very well with the film too) – so I can't imagine what it must have felt like to unprepared audiences in a theatre in the pre-CGI era, people who had never been exposed to such stuntwork in a movie. Even today’s viewers might find their mouths open when a dazed Harold swaggers about on the very edge of the roof after being struck by a weather-vane. No wonder the last shot– with the Boy back on firm ground and in the safety of the Girl’s arms – brings such a sense of release. It is a little like King Kong with a different ending, one where the ape and the blonde are reunited for ever on the rooftop. But is this a happy ending exactly? Even a thousand dollars may not go a very long way, and if the city is going to keep throwing up such challenges perhaps the young man may have been better off with his head in that noose after all.

I watched Safety Last! alone, on DVD, with a prior idea of what the film was about, and I was still deeply stirred by it (the orchestral soundtrack by Carl Davis from 1989 goes very well with the film too) – so I can't imagine what it must have felt like to unprepared audiences in a theatre in the pre-CGI era, people who had never been exposed to such stuntwork in a movie. Even today’s viewers might find their mouths open when a dazed Harold swaggers about on the very edge of the roof after being struck by a weather-vane. No wonder the last shot– with the Boy back on firm ground and in the safety of the Girl’s arms – brings such a sense of release. It is a little like King Kong with a different ending, one where the ape and the blonde are reunited for ever on the rooftop. But is this a happy ending exactly? Even a thousand dollars may not go a very long way, and if the city is going to keep throwing up such challenges perhaps the young man may have been better off with his head in that noose after all.P.S. two shots from films about a struggler in the city. A tram sequence in Safety Last! with hordes of men clinging to the outside of the vehicle and to each other, like bees to a hive:

And Kishore Kumar on a bus in Naukri 30 years later:

Published on February 07, 2014 21:30

February 4, 2014

Kitty litterateurs: on Suniti Namjoshi's Suki and other cat books

[Did this for the magazine Democratic World]

There was an email forward doing the rounds recently, a comparison of hypothetical one-page diary entries written by two house pets – a dog and a cat. The dog’s entry was short, semi-literate and full of sunshine and cheer, with such exclamations as “Oh boy! A car ride! My favourite!” and “Oh boy! Tummy rubs on the couch!” while the cat’s was written in full, elegant sentences and was sardonic and world-weary: the very heading read “Day 183 of my captivity”.

Anyone who knows the two species well should agree that this is a good summary of their broad personality types. And anyone who knows professional writers – at least the ones who brood for hours over the construction of a paragraph or sentence – will agree that temperamentally they tend to be cat-like: mostly reserved, unsocial and irritable, but willing to purr for a short time if a satisfying turn of phrase has been achieved, or a deadline more or less met. There are also practical reasons why writers are more often “cat people” than “dog people”. Dogs are dependent on human attention, needing to be regularly spoken to and taken down for walks, but cats are more self-sufficient, and hence suitable companions for people who spend much of their time in fierce concentration.

In this light, it is interesting to consider the difference in tone between books about dogs and books about cats. The former – especially the ones about life with a pet – tend to be sentimental and emotionally demonstrative, whereas cat books have a certain coolness built into them. And this can be the case even when they belong to the Motivational or Self-Help category. Take David Michie’s very engaging

The Dalai Lama’s Cat

, told in the voice of a kitten who is rescued by the Dalai Lama at a traffic signal near Delhi and brought to Mcleodganj, where she soon settles into the temple complex and becomes known as His Holiness’s Cat (HHC).

In this light, it is interesting to consider the difference in tone between books about dogs and books about cats. The former – especially the ones about life with a pet – tend to be sentimental and emotionally demonstrative, whereas cat books have a certain coolness built into them. And this can be the case even when they belong to the Motivational or Self-Help category. Take David Michie’s very engaging

The Dalai Lama’s Cat

, told in the voice of a kitten who is rescued by the Dalai Lama at a traffic signal near Delhi and brought to Mcleodganj, where she soon settles into the temple complex and becomes known as His Holiness’s Cat (HHC).

HHC – alternately known as Snow Lion and, to her dismay, “Mousie-Tung” – spends much of her time in the company of the Buddhist leader, soaking in his presence (“had he recognised in me a kindred spirit – a sentient being on the same spiritual wavelength as he?”) and listening in as he discusses the conundrums of existence. Each chapter follows a broad format where a human character discovers the need to rethink his attitude to things, and the cat then applies some of these teachings to her own situation, with varying degrees of success. Thus, an insight about how self-absorption can make one sick and unhappy (a valuable lesson for writers, as it happens!) is linked to our narrator coughing up fur balls after spending an inordinate amount of time grooming herself. She realises that a period of self-pity combined with fear of exploring a new setting cost her precious time that she might have spent getting to know a new friend; and she is even inspired to deal with her gluttony, a by-product of being pampered silly.

As an old cynic wary of quick-fix advice and pat life lessons, I am not really a fan of this genre. But The Dalai Lama’s Cat worked for me because even in times of emotional epiphany, the cat nature retains a certain distance. At one point HHC overcomes her feelings of distaste for a new arrival, a dog named Kyi Kyi, when she learns about his sad back-story. “We reached an understanding of sorts,” she says, but then she quickly adds: “I did not, however, climb into his basket and let him lick my face. I’m not that kind of cat. And this is not that kind of book.”

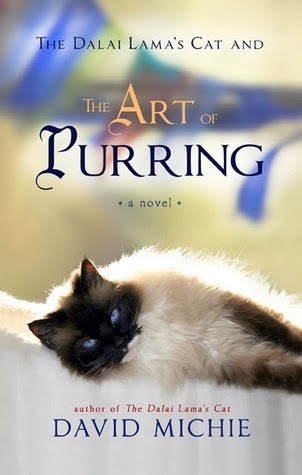

Such emotional reticence can make brief, unexpected flashes of sentimentality very effective. Suniti Namjoshi’s recently published

Suki

, a tribute to her deceased cat, takes the form of conversations between human and feline. They talk about such things as morality, social injustice and hypocrisy, and the tone is mostly droll, faux-philosophical and chatty (or catty). But there are deeply affecting moments too. At one point in the middle of a casual conversation, the ghost-cat remarks that towards the end of her life it had been painful for her to open the cat-flap to go outside, and the author responds with a spontaneous cry of “Oh, Suki!” And another exchange, where the cat mentions that she would have liked to meet the author’s family (who were not animal lovers), should cut deep for anyone who has ever had a special, intense relationship with an animal and been unable to share it with their human world.

Such emotional reticence can make brief, unexpected flashes of sentimentality very effective. Suniti Namjoshi’s recently published

Suki

, a tribute to her deceased cat, takes the form of conversations between human and feline. They talk about such things as morality, social injustice and hypocrisy, and the tone is mostly droll, faux-philosophical and chatty (or catty). But there are deeply affecting moments too. At one point in the middle of a casual conversation, the ghost-cat remarks that towards the end of her life it had been painful for her to open the cat-flap to go outside, and the author responds with a spontaneous cry of “Oh, Suki!” And another exchange, where the cat mentions that she would have liked to meet the author’s family (who were not animal lovers), should cut deep for anyone who has ever had a special, intense relationship with an animal and been unable to share it with their human world.

At the same time, one knows that these conversations are fictional, that Namjoshi is imagining things about the cat’s inner life and rendering them into human language. And so, the book becomes as much about the author herself – it is a form of therapy, a way of examining her deepest feelings, including love, grief and regret. This is also a reminder that there are many types of cat books. Cats can be used to examine a particular milieu as in Pallavi Aiyar’s novel Chinese Whiskers , in which the adventures of two Beijing cats give us a window into aspects of Chinese society including insularity, city-dwellers’ prejudices against migrant workers and the materialism of the young. Or they can serve purely representative or symbolic purposes: Art Spiegelman’s brilliant graphic novel Maus depicts the Holocaust by drawing Jews as mice and their Nazi oppressors as cats, but there is no pretence that the book is about animals.

Even overtly cat-centric books like The Dalai Lama’s Cat don’t always try to provide a detailed picture of the feline world and its tactile sensations, which is why Nilanjana S Roy’s delightful The Wildings , and its sequel

This should resonate with anyone who has long-suspected that there is something otherworldly about cats; that they aren’t letting on everything they know; or that they are, like the cat in that diary entry, plotting something diabolical. “When my cats aren't happy, I’m not happy,” the poet Shelley said once, “because I know they’re just sitting there thinking up ways to get even.” Or to telepathically work themselves into the next book or poem.

[A post about Suniti Namjoshi's The Fabulous Feminist is here]

There was an email forward doing the rounds recently, a comparison of hypothetical one-page diary entries written by two house pets – a dog and a cat. The dog’s entry was short, semi-literate and full of sunshine and cheer, with such exclamations as “Oh boy! A car ride! My favourite!” and “Oh boy! Tummy rubs on the couch!” while the cat’s was written in full, elegant sentences and was sardonic and world-weary: the very heading read “Day 183 of my captivity”.

Anyone who knows the two species well should agree that this is a good summary of their broad personality types. And anyone who knows professional writers – at least the ones who brood for hours over the construction of a paragraph or sentence – will agree that temperamentally they tend to be cat-like: mostly reserved, unsocial and irritable, but willing to purr for a short time if a satisfying turn of phrase has been achieved, or a deadline more or less met. There are also practical reasons why writers are more often “cat people” than “dog people”. Dogs are dependent on human attention, needing to be regularly spoken to and taken down for walks, but cats are more self-sufficient, and hence suitable companions for people who spend much of their time in fierce concentration.

In this light, it is interesting to consider the difference in tone between books about dogs and books about cats. The former – especially the ones about life with a pet – tend to be sentimental and emotionally demonstrative, whereas cat books have a certain coolness built into them. And this can be the case even when they belong to the Motivational or Self-Help category. Take David Michie’s very engaging

The Dalai Lama’s Cat

, told in the voice of a kitten who is rescued by the Dalai Lama at a traffic signal near Delhi and brought to Mcleodganj, where she soon settles into the temple complex and becomes known as His Holiness’s Cat (HHC).

In this light, it is interesting to consider the difference in tone between books about dogs and books about cats. The former – especially the ones about life with a pet – tend to be sentimental and emotionally demonstrative, whereas cat books have a certain coolness built into them. And this can be the case even when they belong to the Motivational or Self-Help category. Take David Michie’s very engaging

The Dalai Lama’s Cat

, told in the voice of a kitten who is rescued by the Dalai Lama at a traffic signal near Delhi and brought to Mcleodganj, where she soon settles into the temple complex and becomes known as His Holiness’s Cat (HHC).HHC – alternately known as Snow Lion and, to her dismay, “Mousie-Tung” – spends much of her time in the company of the Buddhist leader, soaking in his presence (“had he recognised in me a kindred spirit – a sentient being on the same spiritual wavelength as he?”) and listening in as he discusses the conundrums of existence. Each chapter follows a broad format where a human character discovers the need to rethink his attitude to things, and the cat then applies some of these teachings to her own situation, with varying degrees of success. Thus, an insight about how self-absorption can make one sick and unhappy (a valuable lesson for writers, as it happens!) is linked to our narrator coughing up fur balls after spending an inordinate amount of time grooming herself. She realises that a period of self-pity combined with fear of exploring a new setting cost her precious time that she might have spent getting to know a new friend; and she is even inspired to deal with her gluttony, a by-product of being pampered silly.

As an old cynic wary of quick-fix advice and pat life lessons, I am not really a fan of this genre. But The Dalai Lama’s Cat worked for me because even in times of emotional epiphany, the cat nature retains a certain distance. At one point HHC overcomes her feelings of distaste for a new arrival, a dog named Kyi Kyi, when she learns about his sad back-story. “We reached an understanding of sorts,” she says, but then she quickly adds: “I did not, however, climb into his basket and let him lick my face. I’m not that kind of cat. And this is not that kind of book.”

Such emotional reticence can make brief, unexpected flashes of sentimentality very effective. Suniti Namjoshi’s recently published

Suki

, a tribute to her deceased cat, takes the form of conversations between human and feline. They talk about such things as morality, social injustice and hypocrisy, and the tone is mostly droll, faux-philosophical and chatty (or catty). But there are deeply affecting moments too. At one point in the middle of a casual conversation, the ghost-cat remarks that towards the end of her life it had been painful for her to open the cat-flap to go outside, and the author responds with a spontaneous cry of “Oh, Suki!” And another exchange, where the cat mentions that she would have liked to meet the author’s family (who were not animal lovers), should cut deep for anyone who has ever had a special, intense relationship with an animal and been unable to share it with their human world.

Such emotional reticence can make brief, unexpected flashes of sentimentality very effective. Suniti Namjoshi’s recently published

Suki

, a tribute to her deceased cat, takes the form of conversations between human and feline. They talk about such things as morality, social injustice and hypocrisy, and the tone is mostly droll, faux-philosophical and chatty (or catty). But there are deeply affecting moments too. At one point in the middle of a casual conversation, the ghost-cat remarks that towards the end of her life it had been painful for her to open the cat-flap to go outside, and the author responds with a spontaneous cry of “Oh, Suki!” And another exchange, where the cat mentions that she would have liked to meet the author’s family (who were not animal lovers), should cut deep for anyone who has ever had a special, intense relationship with an animal and been unable to share it with their human world.At the same time, one knows that these conversations are fictional, that Namjoshi is imagining things about the cat’s inner life and rendering them into human language. And so, the book becomes as much about the author herself – it is a form of therapy, a way of examining her deepest feelings, including love, grief and regret. This is also a reminder that there are many types of cat books. Cats can be used to examine a particular milieu as in Pallavi Aiyar’s novel Chinese Whiskers , in which the adventures of two Beijing cats give us a window into aspects of Chinese society including insularity, city-dwellers’ prejudices against migrant workers and the materialism of the young. Or they can serve purely representative or symbolic purposes: Art Spiegelman’s brilliant graphic novel Maus depicts the Holocaust by drawing Jews as mice and their Nazi oppressors as cats, but there is no pretence that the book is about animals.

Even overtly cat-centric books like The Dalai Lama’s Cat don’t always try to provide a detailed picture of the feline world and its tactile sensations, which is why Nilanjana S Roy’s delightful The Wildings , and its sequel

This should resonate with anyone who has long-suspected that there is something otherworldly about cats; that they aren’t letting on everything they know; or that they are, like the cat in that diary entry, plotting something diabolical. “When my cats aren't happy, I’m not happy,” the poet Shelley said once, “because I know they’re just sitting there thinking up ways to get even.” Or to telepathically work themselves into the next book or poem.

[A post about Suniti Namjoshi's The Fabulous Feminist is here]

Published on February 04, 2014 19:22

February 3, 2014

All hail The Honey Hunter

When he woke, the sky was green: not blue, but green and brown, a sky of leaves and branches with a moving, shifting land below.Advance word for a book I can’t wait to get my hands on. The Honey Hunter is written by my multi-talented friend Karthika Nair (poet, scriptwriter, dance producer, and fellow Mahabharata-obsessive - we have long, subtextual email conversations about the epic), with breathtaking illustrations by Joëlle Jolivet. The story is about a little boy who loves honey and ventures into

He saw colours flashing, changing, disappearing ... mudskippers and fishing cats and hermit crabs, not one staying still long enough for him to be sure he had seen them.

And beneath it all, beneath the chatter of cormorants, egrets and woodpeckers; alongside the rustle of the terrapin and the pythons, and the heavy tread of the water buffalo, he heard the music of the bees: the hum of gazillions of bees hard at work.

the Sunderbans to get it, reviving an ancient tussle between a demon king in tiger guise and a benevolent Goddess, both of whom ultimately have the forest’s best interests at heart. Lovely, gentle narrative, full of mystery and awe, but also a cautionary tale with a clear-sighted (and non-pedantic) ecological sense. And this plot synopsis doesn’t begin to do it justice.

the Sunderbans to get it, reviving an ancient tussle between a demon king in tiger guise and a benevolent Goddess, both of whom ultimately have the forest’s best interests at heart. Lovely, gentle narrative, full of mystery and awe, but also a cautionary tale with a clear-sighted (and non-pedantic) ecological sense. And this plot synopsis doesn’t begin to do it justice.In any case, I “read” this book in an unusual, fragmented way: I first saw the drawings page by page on a computer in the Zubaan office, but couldn't read the story then because it was the French version, Le Tigre de Miel; subsequently I read the English version in a text-only file. So I haven’t yet experienced the text and images in conjunction, but that will happen soon.

More about the book here, including a short trailer (for the French translation) that provides a glimpse of some of Jolivet’s artwork. The launch is in various cities this month, including at the Kala Ghoda festival in Mumbai and the World Book Fair in Delhi. (Schedule of events here.)

Published on February 03, 2014 04:13

February 1, 2014

Rafa the low-born (tennis at Kurukshetra)

Had to share this. I wrote a piece for the magazine Indian Quarterly recently, about a new crop of epic retellings being done in popular genres such as young romance and the underworld thriller. The piece – which centred on two new books about Karna, one of my childhood literary heroes – ended with a jokey line about how, if I ever did a Mahabharata-retelling myself, I would merge my personal obsessions and present the Kurukshetra war as a series of Grand Slam tennis matches: 128 warriors, falling by the wayside one by one (over 18 days, or over a fortnight), all of it leading up to a grand finale - the decisive Arjuna-Karna battle, cast as a meeting between Roger Federer and my favourite sportsperson Rafael Nadal.

It was a throwaway reference, not central to the piece in any way, so imagine my surprise when I saw a PDF of the story and found that the illustration done for it brought together Karna and Rafa (dressed in Wimbledon whites, including the sleeveless kavacha he wore until a few years ago) in one surreal, bow-and-bandana juxtaposition. I didn't have anything to do with planning the image, so this was most fortuitous, and I must thank the illustrator Salil Sojwal. Here’s the picture:

Illustration: SALIL SOJWAL

Illustration: SALIL SOJWAL

Of course, one is now tempted to make Nadal: Federer = Karna: Arjuna analogies, based on nothing more concrete than the facile perceptions we form of sportspeople. Thus, Roger as the privileged prince and favoured son, all grace and artistry, seemingly born to conquer the world, his destiny pre-written in stone; and Rafa as the dark cloud on his horizon, the upstart shaking up the fraternity with his unconventional style of play and his apparently uncouth mien (which conceals a sweet but defensive nature). Roger pirouetting his way across tennis courts with a sense of entitlement, while Rafa plays catch-up, struggling with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune: chronic injuries, a style of play that doesn’t meet the aesthetic demands of people who want their tennis to be like ballet, and an inability to make himself properly understood – which in one famous case after the 2006 French Open led to public booing because he had been mistranslated. (“Chale jao, suta-putra,” yells the Hastinapura crowd.)

I could go on, but I won’t. Instead here are two photos of cho-chweet bonding between rivals. The first is from the great years of the Roger-Rafa bromance (more on that in this post); the second is from a recent episode of the Star Plus Mahabharat where Karna helps Arjuna (disguised here as a brahmin) lift a chariot wheel out of the mud (!!). Can't see the resemblance? Either there is no poetry in your soul, or you have better things to do with your time.

" "VAMOS!!!"

"VAMOS!!!"

It was a throwaway reference, not central to the piece in any way, so imagine my surprise when I saw a PDF of the story and found that the illustration done for it brought together Karna and Rafa (dressed in Wimbledon whites, including the sleeveless kavacha he wore until a few years ago) in one surreal, bow-and-bandana juxtaposition. I didn't have anything to do with planning the image, so this was most fortuitous, and I must thank the illustrator Salil Sojwal. Here’s the picture:

Illustration: SALIL SOJWAL

Illustration: SALIL SOJWALOf course, one is now tempted to make Nadal: Federer = Karna: Arjuna analogies, based on nothing more concrete than the facile perceptions we form of sportspeople. Thus, Roger as the privileged prince and favoured son, all grace and artistry, seemingly born to conquer the world, his destiny pre-written in stone; and Rafa as the dark cloud on his horizon, the upstart shaking up the fraternity with his unconventional style of play and his apparently uncouth mien (which conceals a sweet but defensive nature). Roger pirouetting his way across tennis courts with a sense of entitlement, while Rafa plays catch-up, struggling with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune: chronic injuries, a style of play that doesn’t meet the aesthetic demands of people who want their tennis to be like ballet, and an inability to make himself properly understood – which in one famous case after the 2006 French Open led to public booing because he had been mistranslated. (“Chale jao, suta-putra,” yells the Hastinapura crowd.)

I could go on, but I won’t. Instead here are two photos of cho-chweet bonding between rivals. The first is from the great years of the Roger-Rafa bromance (more on that in this post); the second is from a recent episode of the Star Plus Mahabharat where Karna helps Arjuna (disguised here as a brahmin) lift a chariot wheel out of the mud (!!). Can't see the resemblance? Either there is no poetry in your soul, or you have better things to do with your time.

"

"VAMOS!!!"

"VAMOS!!!"

Published on February 01, 2014 01:12

January 23, 2014

Sleaze and the unmanly man - notes on Miss Lovely

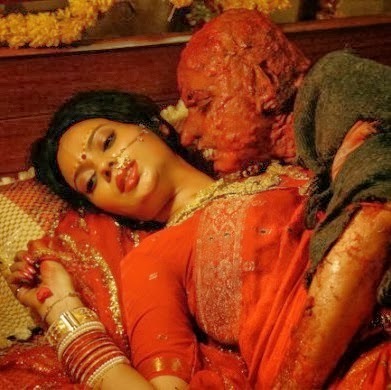

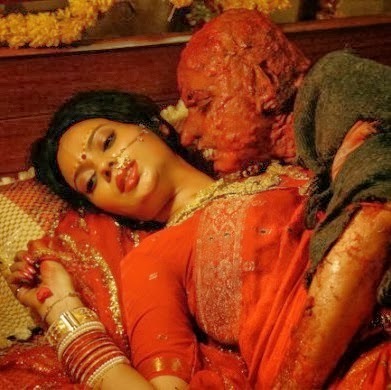

At one point in Ashim Ahluwalia’s

Miss Lovely

, a soft-core sex scene is being shot for a horror-titillation movie – the sort of C-grade movie that the Duggal brothers Vicky (Anil George) and Sonu (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) specialise in. A bosomy starlet, writhing on a bed in bridal wear, is being given directions – “Tera mard na-mard hai” (“Your husband is impotent”) – and we get a vague sense of what the scene is about: the woman on the bed has her eyes closed or turned away (in the manner expected of a good Indian bride), and so she doesn’t realise that she is being necked not by her husband but by a scaly-headed monster.

The film being shot is a cheesy, low-budget thing that might make the work of the Ramsays seem refined in comparison, and the monster looks more comical than scary. But the contrast between a na-mard (which can be shorthand for a passive, hence “effeminate” man) and a rapacious, hyper-masculine bully is also at the heart of Miss Lovely’s own plot. Of the movie-making Duggals, the younger brother Sonu – our point of entry into the film, because we are privy to his inner thoughts and personal stirrings – is effete and dreamy-eyed, and seems to want to break away from this world. Vicky, on the other hand, is a ruffian who mockingly says “Bada mard bannta hai” when his brother tries to strike out for himself. He is the real fiend here, more of a threat than the badly made up monster in that sex scene could ever be, and he is presented in menacing terms: in one scene in a darkened disco, there is a striking shot of him looking down from a height, a red light next to him blinking away as if to signal Danger.

The film being shot is a cheesy, low-budget thing that might make the work of the Ramsays seem refined in comparison, and the monster looks more comical than scary. But the contrast between a na-mard (which can be shorthand for a passive, hence “effeminate” man) and a rapacious, hyper-masculine bully is also at the heart of Miss Lovely’s own plot. Of the movie-making Duggals, the younger brother Sonu – our point of entry into the film, because we are privy to his inner thoughts and personal stirrings – is effete and dreamy-eyed, and seems to want to break away from this world. Vicky, on the other hand, is a ruffian who mockingly says “Bada mard bannta hai” when his brother tries to strike out for himself. He is the real fiend here, more of a threat than the badly made up monster in that sex scene could ever be, and he is presented in menacing terms: in one scene in a darkened disco, there is a striking shot of him looking down from a height, a red light next to him blinking away as if to signal Danger.

The brothers will fall out over a seemingly innocent girl named Pinky (Niharika Singh), who wants a break in films and who Sonu becomes besotted with. But that makes Miss Lovely sound more narrative-driven than it is. The idea here isn’t so much to tell “a story” (the plot, such as it is, could be scribbled on the palm of your hand, much like Pinky quickly writing her phone number down on Sonu’s hand during a stolen moment) but to create the mood of a particular world – the world of small-time moviemakers in the late 1980s, conducting shady deals, negotiating the chaos of a profession where things have to be done fast, in hurriedly improvised locations, with the knowledge that a police raid may always be around the corner.

Being abstract and often anti-narrative, this is a slow-moving film (I’ll confess my attention wandered at times) but it tries to do something very interesting: to admit us into this milieu, and the states of mind you might find in it, without over-explaining anything – letting the visuals, the art direction and the sound design do most of the work instead. Much of it is shot in the style of a handheld-camera documentary. There are relatively few outdoor scenes, the main impression is of oppressive interiors, rooms that are small and dimly lit and overcrowded, characters who are almost brushing up against the camera; there is a sense of drifting through shadowy places and hearing faraway voices as if through a tunnel. (I read that director Ahluwalia counts Seijun Suzuki among his influences. I don’t know Suzuki’s films apart from Branded to Kill, but parts of Miss Lovely reminded me of the work of another non-mainstream Japanese director of the 1960s, Nobuo Nagakawa, especially

Jigoku

, which offered a stylised vision of hell and its lost souls, looking for small salvations.) In fact, a viewer can get so steeped in this setting that it may come as a minor shock to hear – in one scene – the polished, anodyne voice of an English-speaking newsreader talking about exploitation movies and forced prostitution. These incidents seems like they belong to another world, the newsreader says in what sounds like a dispassionately patronising tone, and of course, from her perspective, they do.

Being abstract and often anti-narrative, this is a slow-moving film (I’ll confess my attention wandered at times) but it tries to do something very interesting: to admit us into this milieu, and the states of mind you might find in it, without over-explaining anything – letting the visuals, the art direction and the sound design do most of the work instead. Much of it is shot in the style of a handheld-camera documentary. There are relatively few outdoor scenes, the main impression is of oppressive interiors, rooms that are small and dimly lit and overcrowded, characters who are almost brushing up against the camera; there is a sense of drifting through shadowy places and hearing faraway voices as if through a tunnel. (I read that director Ahluwalia counts Seijun Suzuki among his influences. I don’t know Suzuki’s films apart from Branded to Kill, but parts of Miss Lovely reminded me of the work of another non-mainstream Japanese director of the 1960s, Nobuo Nagakawa, especially

Jigoku

, which offered a stylised vision of hell and its lost souls, looking for small salvations.) In fact, a viewer can get so steeped in this setting that it may come as a minor shock to hear – in one scene – the polished, anodyne voice of an English-speaking newsreader talking about exploitation movies and forced prostitution. These incidents seems like they belong to another world, the newsreader says in what sounds like a dispassionately patronising tone, and of course, from her perspective, they do.

But this is also an “other world” film in the sense of the past being a foreign country - it is a reminder that the late 80s and the early 90s were a time of transition, in India’s metropolises at least, and in the entertainment industry: the last years of the video-cassette culture, the shift to an era of multiple TV channels(!) and the greater possibilities they brought for home entertainment. We see Ambassadors and Fiats (and a few Maruti 800s) on the roads, black-and-white TV screens with pictures barely visible through static. Nataraj pencil ads play over transistors and little boys fight each other with makeshift maces, no doubt in imitation of the TV Mahabharata which would have been playing at the time. Even the film’s opening titles play like a homage to 1980s B-movies (or some 80s “A-movies” for that matter) – garish background colours, names like Biddu and Nazia Hassan improbably sharing space with Ilaiyaraaja.

But this is also an “other world” film in the sense of the past being a foreign country - it is a reminder that the late 80s and the early 90s were a time of transition, in India’s metropolises at least, and in the entertainment industry: the last years of the video-cassette culture, the shift to an era of multiple TV channels(!) and the greater possibilities they brought for home entertainment. We see Ambassadors and Fiats (and a few Maruti 800s) on the roads, black-and-white TV screens with pictures barely visible through static. Nataraj pencil ads play over transistors and little boys fight each other with makeshift maces, no doubt in imitation of the TV Mahabharata which would have been playing at the time. Even the film’s opening titles play like a homage to 1980s B-movies (or some 80s “A-movies” for that matter) – garish background colours, names like Biddu and Nazia Hassan improbably sharing space with Ilaiyaraaja.

At the same time there is nothing dated about the contrast between the supposedly glamorous world of show-business (even in a C-movie universe) and behind-the-scene realities. A newspaper clipping places a photo of a starlet smiling out at the camera next to a picture of her muddy corpse found in a swamp. A mother tells a producer that her daughter will do anything and gets the approving response, “Bahut acchhe sanskaar deeye hain”. Throughout, one is aware of the divide between people who are motivated and single-minded enough to make a life for themselves in this world, and those who are unable to.

clipping places a photo of a starlet smiling out at the camera next to a picture of her muddy corpse found in a swamp. A mother tells a producer that her daughter will do anything and gets the approving response, “Bahut acchhe sanskaar deeye hain”. Throughout, one is aware of the divide between people who are motivated and single-minded enough to make a life for themselves in this world, and those who are unable to.

Which brings us back to Sonu, for Miss Lovely also begs the question: what might happen when a man with a strong introspective impulse, given to philosophising and dreaming, finds himself born to the manor of a coarse, cut-throat world like this one? His voiceovers (which overlap sometimes with the dialogue in a scene) include lines like “Aadmi ka level hona chahiye – level nahin toh aadmi kya”. He is too idealistic and too meditative to join his brother in playing the “bada game”. And for me one problem was that I didn’t really feel like I had got to know him, or understand how he came to be working in this business for so long without having his heart in it. One shot in that disco scene has Sonu, left in the lurch, holding two glasses and looking confused as the smoke of the dance floor envelops him. This film has many intriguing qualities, but its protagonist – the person we want to relate to or at least empathise with – remains as distant and hazy as that shot suggests.

The film being shot is a cheesy, low-budget thing that might make the work of the Ramsays seem refined in comparison, and the monster looks more comical than scary. But the contrast between a na-mard (which can be shorthand for a passive, hence “effeminate” man) and a rapacious, hyper-masculine bully is also at the heart of Miss Lovely’s own plot. Of the movie-making Duggals, the younger brother Sonu – our point of entry into the film, because we are privy to his inner thoughts and personal stirrings – is effete and dreamy-eyed, and seems to want to break away from this world. Vicky, on the other hand, is a ruffian who mockingly says “Bada mard bannta hai” when his brother tries to strike out for himself. He is the real fiend here, more of a threat than the badly made up monster in that sex scene could ever be, and he is presented in menacing terms: in one scene in a darkened disco, there is a striking shot of him looking down from a height, a red light next to him blinking away as if to signal Danger.

The film being shot is a cheesy, low-budget thing that might make the work of the Ramsays seem refined in comparison, and the monster looks more comical than scary. But the contrast between a na-mard (which can be shorthand for a passive, hence “effeminate” man) and a rapacious, hyper-masculine bully is also at the heart of Miss Lovely’s own plot. Of the movie-making Duggals, the younger brother Sonu – our point of entry into the film, because we are privy to his inner thoughts and personal stirrings – is effete and dreamy-eyed, and seems to want to break away from this world. Vicky, on the other hand, is a ruffian who mockingly says “Bada mard bannta hai” when his brother tries to strike out for himself. He is the real fiend here, more of a threat than the badly made up monster in that sex scene could ever be, and he is presented in menacing terms: in one scene in a darkened disco, there is a striking shot of him looking down from a height, a red light next to him blinking away as if to signal Danger.The brothers will fall out over a seemingly innocent girl named Pinky (Niharika Singh), who wants a break in films and who Sonu becomes besotted with. But that makes Miss Lovely sound more narrative-driven than it is. The idea here isn’t so much to tell “a story” (the plot, such as it is, could be scribbled on the palm of your hand, much like Pinky quickly writing her phone number down on Sonu’s hand during a stolen moment) but to create the mood of a particular world – the world of small-time moviemakers in the late 1980s, conducting shady deals, negotiating the chaos of a profession where things have to be done fast, in hurriedly improvised locations, with the knowledge that a police raid may always be around the corner.

Being abstract and often anti-narrative, this is a slow-moving film (I’ll confess my attention wandered at times) but it tries to do something very interesting: to admit us into this milieu, and the states of mind you might find in it, without over-explaining anything – letting the visuals, the art direction and the sound design do most of the work instead. Much of it is shot in the style of a handheld-camera documentary. There are relatively few outdoor scenes, the main impression is of oppressive interiors, rooms that are small and dimly lit and overcrowded, characters who are almost brushing up against the camera; there is a sense of drifting through shadowy places and hearing faraway voices as if through a tunnel. (I read that director Ahluwalia counts Seijun Suzuki among his influences. I don’t know Suzuki’s films apart from Branded to Kill, but parts of Miss Lovely reminded me of the work of another non-mainstream Japanese director of the 1960s, Nobuo Nagakawa, especially

Jigoku

, which offered a stylised vision of hell and its lost souls, looking for small salvations.) In fact, a viewer can get so steeped in this setting that it may come as a minor shock to hear – in one scene – the polished, anodyne voice of an English-speaking newsreader talking about exploitation movies and forced prostitution. These incidents seems like they belong to another world, the newsreader says in what sounds like a dispassionately patronising tone, and of course, from her perspective, they do.

Being abstract and often anti-narrative, this is a slow-moving film (I’ll confess my attention wandered at times) but it tries to do something very interesting: to admit us into this milieu, and the states of mind you might find in it, without over-explaining anything – letting the visuals, the art direction and the sound design do most of the work instead. Much of it is shot in the style of a handheld-camera documentary. There are relatively few outdoor scenes, the main impression is of oppressive interiors, rooms that are small and dimly lit and overcrowded, characters who are almost brushing up against the camera; there is a sense of drifting through shadowy places and hearing faraway voices as if through a tunnel. (I read that director Ahluwalia counts Seijun Suzuki among his influences. I don’t know Suzuki’s films apart from Branded to Kill, but parts of Miss Lovely reminded me of the work of another non-mainstream Japanese director of the 1960s, Nobuo Nagakawa, especially

Jigoku

, which offered a stylised vision of hell and its lost souls, looking for small salvations.) In fact, a viewer can get so steeped in this setting that it may come as a minor shock to hear – in one scene – the polished, anodyne voice of an English-speaking newsreader talking about exploitation movies and forced prostitution. These incidents seems like they belong to another world, the newsreader says in what sounds like a dispassionately patronising tone, and of course, from her perspective, they do. But this is also an “other world” film in the sense of the past being a foreign country - it is a reminder that the late 80s and the early 90s were a time of transition, in India’s metropolises at least, and in the entertainment industry: the last years of the video-cassette culture, the shift to an era of multiple TV channels(!) and the greater possibilities they brought for home entertainment. We see Ambassadors and Fiats (and a few Maruti 800s) on the roads, black-and-white TV screens with pictures barely visible through static. Nataraj pencil ads play over transistors and little boys fight each other with makeshift maces, no doubt in imitation of the TV Mahabharata which would have been playing at the time. Even the film’s opening titles play like a homage to 1980s B-movies (or some 80s “A-movies” for that matter) – garish background colours, names like Biddu and Nazia Hassan improbably sharing space with Ilaiyaraaja.

But this is also an “other world” film in the sense of the past being a foreign country - it is a reminder that the late 80s and the early 90s were a time of transition, in India’s metropolises at least, and in the entertainment industry: the last years of the video-cassette culture, the shift to an era of multiple TV channels(!) and the greater possibilities they brought for home entertainment. We see Ambassadors and Fiats (and a few Maruti 800s) on the roads, black-and-white TV screens with pictures barely visible through static. Nataraj pencil ads play over transistors and little boys fight each other with makeshift maces, no doubt in imitation of the TV Mahabharata which would have been playing at the time. Even the film’s opening titles play like a homage to 1980s B-movies (or some 80s “A-movies” for that matter) – garish background colours, names like Biddu and Nazia Hassan improbably sharing space with Ilaiyaraaja. At the same time there is nothing dated about the contrast between the supposedly glamorous world of show-business (even in a C-movie universe) and behind-the-scene realities. A newspaper

clipping places a photo of a starlet smiling out at the camera next to a picture of her muddy corpse found in a swamp. A mother tells a producer that her daughter will do anything and gets the approving response, “Bahut acchhe sanskaar deeye hain”. Throughout, one is aware of the divide between people who are motivated and single-minded enough to make a life for themselves in this world, and those who are unable to.