Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 73

October 15, 2013

Heroism on an intimate scale – about Hansal Mehta’s Shahid

“Mr Shahid, you have to let it go,” a judge tells Shahid Azmi (Rajkumar Yadav) in the new biopic about the lawyer and human rights activist who was murdered in 2010. Other people say much the same thing over the course of this film, but “letting go” doesn't come easily to Shahid. He might – in an attempt to break the ice with a new client – crack a lame joke about lawyers’ ethical codes, but he is dead serious about his work and goes about it with quiet, unshowy determination.

As Shahid shows us, though, it wasn’t always that way – this is a story about personal growth, about finding your place in the world. When we first see Azmi in Hansal Mehta’s film, his face is a blur, then his features come slowly into focus. The shot anticipates a narrative arc where a confused young man will grow in stature and confidence, his personality becoming more sharply defined as time passes. If you watch the early scenes in Shahid without knowing much about the real Shahid Azmi’s life, you might be unsure what he’s about, what his motivations and impulses are, what he is going to do next (and he is probably just as uncertain himself at this point, vacillating between the company of a militant and an intellectual activist during a prison stint). But by the end, he has become an unlikely hero.

As Shahid shows us, though, it wasn’t always that way – this is a story about personal growth, about finding your place in the world. When we first see Azmi in Hansal Mehta’s film, his face is a blur, then his features come slowly into focus. The shot anticipates a narrative arc where a confused young man will grow in stature and confidence, his personality becoming more sharply defined as time passes. If you watch the early scenes in Shahid without knowing much about the real Shahid Azmi’s life, you might be unsure what he’s about, what his motivations and impulses are, what he is going to do next (and he is probably just as uncertain himself at this point, vacillating between the company of a militant and an intellectual activist during a prison stint). But by the end, he has become an unlikely hero.

Actually, “hero”, with its many filmi connotations, might seem an inappropriate word given the type of film this is. Shahid is subdued and un-dramatic, which is strange since one of its very first scenes (set during the 1992-93 Bombay riots) has the young Shahid recoiling in shock as a burning man lurches towards him. This is followed by vignettes from Shahid’s early life: his brief time in a militant training camp in Kashmir, his efforts to educate himself and transcend the disadvantages of a poor background, his seven years in jail after a stage-managed arrest under TADA. When he is released, he sets about working for voiceless innocents who might find themselves in similar situations: lower-class Muslims who are being railroaded because they are soft targets.

This is not material that lends itself to understated treatment, especially in our communally fervid times. Yet Shahid somehow manages not to be an overtly political film, full of large, bird’s-eye-view narratives about discrimination and injustice. Apart from a couple of short monologues – delivered without flourish – it isn’t much concerned with the sweeping historical view of things. Instead, like its protagonist, it stays in the here and now: it makes its points by operating at ground level, showing the daily functioning of the judiciary, the lack of transparency in the workings of bodies that all of us depend on - in the process suggesting how systemic flaws and prejudice can spread across levels (starting with foul-mouthed, inadequately sensitised policemen), how well-intentioned people can become cogs, and how underprivileged people can find the cards stacked against them.

This ground-level view is reflected in the film’s form, which is more that of the handheld-camera docu-drama than of a dramatic feature. The shots of Azmi in court, bickering with prosecution lawyers and judges, have the spare, naturalistic feel of Cinéma vérité. What we see here is not the grand courtroom of mainstream Hindi film and drama – the stylised, allegorical place where injustice and justice are meted out in turn, where lies and truth are in timeless conflict – but a much more mundane setting, and the lawyers are not suave show-offs but hassled, sweat-soaked people, speaking legalese almost mechanically, worn out from going through the same routine day after day. Of course, important things ARE happening here, life-changing decisions are being made, but the image of the court as a theatre – or a purgatory for souls whose fate lies in Justice’s scales – is thoroughly de-glamorized. Even the dubious witnesses (such as the man who claims to have seen something important during a holiday in Nepal, and recites key-words like “momos”, but can’t remember other basic details about his trip) aren’t smug or slimy character types invested in ruining innocent lives; they are nervous people who may have reasons for doing what they are doing. (Perhaps they believe the people they are fingering are definitely guilty, and the law simply needs their help to get a conviction.)

This ground-level view is reflected in the film’s form, which is more that of the handheld-camera docu-drama than of a dramatic feature. The shots of Azmi in court, bickering with prosecution lawyers and judges, have the spare, naturalistic feel of Cinéma vérité. What we see here is not the grand courtroom of mainstream Hindi film and drama – the stylised, allegorical place where injustice and justice are meted out in turn, where lies and truth are in timeless conflict – but a much more mundane setting, and the lawyers are not suave show-offs but hassled, sweat-soaked people, speaking legalese almost mechanically, worn out from going through the same routine day after day. Of course, important things ARE happening here, life-changing decisions are being made, but the image of the court as a theatre – or a purgatory for souls whose fate lies in Justice’s scales – is thoroughly de-glamorized. Even the dubious witnesses (such as the man who claims to have seen something important during a holiday in Nepal, and recites key-words like “momos”, but can’t remember other basic details about his trip) aren’t smug or slimy character types invested in ruining innocent lives; they are nervous people who may have reasons for doing what they are doing. (Perhaps they believe the people they are fingering are definitely guilty, and the law simply needs their help to get a conviction.)

And amidst this bedlam, here is Shahid Azmi doing whatever he can do, fighting the good fight not as a superhero crusader but as an ordinary, flesh-and-blood man who can’t always look his wife in the eye when she asks him, what about your responsibilities to your family? This is heroism on an intimate, prosaic meter. Even when a prosecution lawyer makes an insinuation about Azmi having served time in jail and been in Kashmir with militants, Shahid’s reaction is a poignant mix of outrage and defensiveness (“I was never a terrorist OR a radical,” he says). There are no hyper-dramatic speeches, no grandstanding, and this is why Rajkumar Yadav (who is consistently excellent in unglamorous parts, and even more unlikely than Nawazuddin Siddiqui to develop actorly tics or become associated with a particular character type) is perfect for this sort of film. It is a cliché to say of a good performance that you forget about the actor and only register the character (and it isn’t a cliché I think much of, because I usually manage to appreciate great acting while being perfectly aware that it IS acting), but Yadav comes very close to that ideal here.

And amidst this bedlam, here is Shahid Azmi doing whatever he can do, fighting the good fight not as a superhero crusader but as an ordinary, flesh-and-blood man who can’t always look his wife in the eye when she asks him, what about your responsibilities to your family? This is heroism on an intimate, prosaic meter. Even when a prosecution lawyer makes an insinuation about Azmi having served time in jail and been in Kashmir with militants, Shahid’s reaction is a poignant mix of outrage and defensiveness (“I was never a terrorist OR a radical,” he says). There are no hyper-dramatic speeches, no grandstanding, and this is why Rajkumar Yadav (who is consistently excellent in unglamorous parts, and even more unlikely than Nawazuddin Siddiqui to develop actorly tics or become associated with a particular character type) is perfect for this sort of film. It is a cliché to say of a good performance that you forget about the actor and only register the character (and it isn’t a cliché I think much of, because I usually manage to appreciate great acting while being perfectly aware that it IS acting), but Yadav comes very close to that ideal here.

The other performances – such as by Vipin Sharma as a prosecuting lawyer and Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub as Shahid's brother Arif – are very good too, bringing integrity to scenes that might otherwise have become trite. And while the emphasis on verisimilitude (right down to shooting some scenes in the real Shahid Azmi’s office) works well, there are also some effective dramatic touches, such as a scene where Shahid and his wife Mariam (Prabhleen Sandhu) argue near the kitchen, she brushes her hand in frustration against some of the utensils, and the resultant clattering of a steel lid continues for a good 10 or 15 seconds on the soundtrack, a tinny accompaniment to their continuing conversation.

I liked the economy of the storytelling too: everything isn’t spelled out, the viewer is allowed to fill in the gaps, make leaps and connections. In the early scenes particularly, we get snapshots from Shahid’s life – appropriate perhaps for a story about a man whose life was cut short much too soon, who never got a chance to realise his full potential or do everything he wanted to do. There are small parts here – cameos, really – for Kay Kay Menon and Tigmanshu Dhulia as people Shahid meets on the course of his journey from naif to potential jihadi to believing that you can only change the system by being part of it. Watching the film, I kept getting the impression that a longer (more flabby, more didactic) cut exists; that (for example) Menon and Dhulia may have had larger roles, and that the director and editor showed discernment in paring the film down to its current length. In one scene, Shahid proposes to Mariam – who is his client at the time, and a divorcee – and she seems outraged and walks out on him; but then there is an immediate cut to them exiting a courthouse together after their low-key wedding. Apart from leaving out details that aren’t relevant to the film’s immediate purpose, this sudden cut is a reminder of Shahid’s persistence, and it also lets us conjecture what may have happened: perhaps Mariam – because of the conservative assumptions of the milieu she grew up in –was so taken aback by Shahid’s proposal that she simply didn’t know how to respond, and took some time to come around.

I liked the economy of the storytelling too: everything isn’t spelled out, the viewer is allowed to fill in the gaps, make leaps and connections. In the early scenes particularly, we get snapshots from Shahid’s life – appropriate perhaps for a story about a man whose life was cut short much too soon, who never got a chance to realise his full potential or do everything he wanted to do. There are small parts here – cameos, really – for Kay Kay Menon and Tigmanshu Dhulia as people Shahid meets on the course of his journey from naif to potential jihadi to believing that you can only change the system by being part of it. Watching the film, I kept getting the impression that a longer (more flabby, more didactic) cut exists; that (for example) Menon and Dhulia may have had larger roles, and that the director and editor showed discernment in paring the film down to its current length. In one scene, Shahid proposes to Mariam – who is his client at the time, and a divorcee – and she seems outraged and walks out on him; but then there is an immediate cut to them exiting a courthouse together after their low-key wedding. Apart from leaving out details that aren’t relevant to the film’s immediate purpose, this sudden cut is a reminder of Shahid’s persistence, and it also lets us conjecture what may have happened: perhaps Mariam – because of the conservative assumptions of the milieu she grew up in –was so taken aback by Shahid’s proposal that she simply didn’t know how to respond, and took some time to come around.

In any case, the world of the lower-class Indian Muslim – under-educated, vulnerable to fear and paranoia, exploited by politicians as well as religious heads – is very much in the background of this film, even though the script doesn’t emphasise it. We never forget the social milieu Shahid hails from, and there are glimpses of cultural conflicts and inner turmoil, as in the scene where he takes his wife to meet his family for the first time and she is appalled that he is asking her to do something she has never done, to wear a burkha (“just this once, never again” he pleads, but in the desperation he shows, one can see where the “just this once” might lead in the future). Scenes like this make Shahid’s personal growth and self-actualisation even more creditable, because we are reminded of the many things he had to overcome, the many small battles he had to win. This isn’t a man to whom heroism comes naturally, he has to grow into it. And by the end, this intense, low-key film has us believing in him.

In any case, the world of the lower-class Indian Muslim – under-educated, vulnerable to fear and paranoia, exploited by politicians as well as religious heads – is very much in the background of this film, even though the script doesn’t emphasise it. We never forget the social milieu Shahid hails from, and there are glimpses of cultural conflicts and inner turmoil, as in the scene where he takes his wife to meet his family for the first time and she is appalled that he is asking her to do something she has never done, to wear a burkha (“just this once, never again” he pleads, but in the desperation he shows, one can see where the “just this once” might lead in the future). Scenes like this make Shahid’s personal growth and self-actualisation even more creditable, because we are reminded of the many things he had to overcome, the many small battles he had to win. This isn’t a man to whom heroism comes naturally, he has to grow into it. And by the end, this intense, low-key film has us believing in him.

As Shahid shows us, though, it wasn’t always that way – this is a story about personal growth, about finding your place in the world. When we first see Azmi in Hansal Mehta’s film, his face is a blur, then his features come slowly into focus. The shot anticipates a narrative arc where a confused young man will grow in stature and confidence, his personality becoming more sharply defined as time passes. If you watch the early scenes in Shahid without knowing much about the real Shahid Azmi’s life, you might be unsure what he’s about, what his motivations and impulses are, what he is going to do next (and he is probably just as uncertain himself at this point, vacillating between the company of a militant and an intellectual activist during a prison stint). But by the end, he has become an unlikely hero.

As Shahid shows us, though, it wasn’t always that way – this is a story about personal growth, about finding your place in the world. When we first see Azmi in Hansal Mehta’s film, his face is a blur, then his features come slowly into focus. The shot anticipates a narrative arc where a confused young man will grow in stature and confidence, his personality becoming more sharply defined as time passes. If you watch the early scenes in Shahid without knowing much about the real Shahid Azmi’s life, you might be unsure what he’s about, what his motivations and impulses are, what he is going to do next (and he is probably just as uncertain himself at this point, vacillating between the company of a militant and an intellectual activist during a prison stint). But by the end, he has become an unlikely hero. Actually, “hero”, with its many filmi connotations, might seem an inappropriate word given the type of film this is. Shahid is subdued and un-dramatic, which is strange since one of its very first scenes (set during the 1992-93 Bombay riots) has the young Shahid recoiling in shock as a burning man lurches towards him. This is followed by vignettes from Shahid’s early life: his brief time in a militant training camp in Kashmir, his efforts to educate himself and transcend the disadvantages of a poor background, his seven years in jail after a stage-managed arrest under TADA. When he is released, he sets about working for voiceless innocents who might find themselves in similar situations: lower-class Muslims who are being railroaded because they are soft targets.

This is not material that lends itself to understated treatment, especially in our communally fervid times. Yet Shahid somehow manages not to be an overtly political film, full of large, bird’s-eye-view narratives about discrimination and injustice. Apart from a couple of short monologues – delivered without flourish – it isn’t much concerned with the sweeping historical view of things. Instead, like its protagonist, it stays in the here and now: it makes its points by operating at ground level, showing the daily functioning of the judiciary, the lack of transparency in the workings of bodies that all of us depend on - in the process suggesting how systemic flaws and prejudice can spread across levels (starting with foul-mouthed, inadequately sensitised policemen), how well-intentioned people can become cogs, and how underprivileged people can find the cards stacked against them.

This ground-level view is reflected in the film’s form, which is more that of the handheld-camera docu-drama than of a dramatic feature. The shots of Azmi in court, bickering with prosecution lawyers and judges, have the spare, naturalistic feel of Cinéma vérité. What we see here is not the grand courtroom of mainstream Hindi film and drama – the stylised, allegorical place where injustice and justice are meted out in turn, where lies and truth are in timeless conflict – but a much more mundane setting, and the lawyers are not suave show-offs but hassled, sweat-soaked people, speaking legalese almost mechanically, worn out from going through the same routine day after day. Of course, important things ARE happening here, life-changing decisions are being made, but the image of the court as a theatre – or a purgatory for souls whose fate lies in Justice’s scales – is thoroughly de-glamorized. Even the dubious witnesses (such as the man who claims to have seen something important during a holiday in Nepal, and recites key-words like “momos”, but can’t remember other basic details about his trip) aren’t smug or slimy character types invested in ruining innocent lives; they are nervous people who may have reasons for doing what they are doing. (Perhaps they believe the people they are fingering are definitely guilty, and the law simply needs their help to get a conviction.)

This ground-level view is reflected in the film’s form, which is more that of the handheld-camera docu-drama than of a dramatic feature. The shots of Azmi in court, bickering with prosecution lawyers and judges, have the spare, naturalistic feel of Cinéma vérité. What we see here is not the grand courtroom of mainstream Hindi film and drama – the stylised, allegorical place where injustice and justice are meted out in turn, where lies and truth are in timeless conflict – but a much more mundane setting, and the lawyers are not suave show-offs but hassled, sweat-soaked people, speaking legalese almost mechanically, worn out from going through the same routine day after day. Of course, important things ARE happening here, life-changing decisions are being made, but the image of the court as a theatre – or a purgatory for souls whose fate lies in Justice’s scales – is thoroughly de-glamorized. Even the dubious witnesses (such as the man who claims to have seen something important during a holiday in Nepal, and recites key-words like “momos”, but can’t remember other basic details about his trip) aren’t smug or slimy character types invested in ruining innocent lives; they are nervous people who may have reasons for doing what they are doing. (Perhaps they believe the people they are fingering are definitely guilty, and the law simply needs their help to get a conviction.) And amidst this bedlam, here is Shahid Azmi doing whatever he can do, fighting the good fight not as a superhero crusader but as an ordinary, flesh-and-blood man who can’t always look his wife in the eye when she asks him, what about your responsibilities to your family? This is heroism on an intimate, prosaic meter. Even when a prosecution lawyer makes an insinuation about Azmi having served time in jail and been in Kashmir with militants, Shahid’s reaction is a poignant mix of outrage and defensiveness (“I was never a terrorist OR a radical,” he says). There are no hyper-dramatic speeches, no grandstanding, and this is why Rajkumar Yadav (who is consistently excellent in unglamorous parts, and even more unlikely than Nawazuddin Siddiqui to develop actorly tics or become associated with a particular character type) is perfect for this sort of film. It is a cliché to say of a good performance that you forget about the actor and only register the character (and it isn’t a cliché I think much of, because I usually manage to appreciate great acting while being perfectly aware that it IS acting), but Yadav comes very close to that ideal here.

And amidst this bedlam, here is Shahid Azmi doing whatever he can do, fighting the good fight not as a superhero crusader but as an ordinary, flesh-and-blood man who can’t always look his wife in the eye when she asks him, what about your responsibilities to your family? This is heroism on an intimate, prosaic meter. Even when a prosecution lawyer makes an insinuation about Azmi having served time in jail and been in Kashmir with militants, Shahid’s reaction is a poignant mix of outrage and defensiveness (“I was never a terrorist OR a radical,” he says). There are no hyper-dramatic speeches, no grandstanding, and this is why Rajkumar Yadav (who is consistently excellent in unglamorous parts, and even more unlikely than Nawazuddin Siddiqui to develop actorly tics or become associated with a particular character type) is perfect for this sort of film. It is a cliché to say of a good performance that you forget about the actor and only register the character (and it isn’t a cliché I think much of, because I usually manage to appreciate great acting while being perfectly aware that it IS acting), but Yadav comes very close to that ideal here. The other performances – such as by Vipin Sharma as a prosecuting lawyer and Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub as Shahid's brother Arif – are very good too, bringing integrity to scenes that might otherwise have become trite. And while the emphasis on verisimilitude (right down to shooting some scenes in the real Shahid Azmi’s office) works well, there are also some effective dramatic touches, such as a scene where Shahid and his wife Mariam (Prabhleen Sandhu) argue near the kitchen, she brushes her hand in frustration against some of the utensils, and the resultant clattering of a steel lid continues for a good 10 or 15 seconds on the soundtrack, a tinny accompaniment to their continuing conversation.

I liked the economy of the storytelling too: everything isn’t spelled out, the viewer is allowed to fill in the gaps, make leaps and connections. In the early scenes particularly, we get snapshots from Shahid’s life – appropriate perhaps for a story about a man whose life was cut short much too soon, who never got a chance to realise his full potential or do everything he wanted to do. There are small parts here – cameos, really – for Kay Kay Menon and Tigmanshu Dhulia as people Shahid meets on the course of his journey from naif to potential jihadi to believing that you can only change the system by being part of it. Watching the film, I kept getting the impression that a longer (more flabby, more didactic) cut exists; that (for example) Menon and Dhulia may have had larger roles, and that the director and editor showed discernment in paring the film down to its current length. In one scene, Shahid proposes to Mariam – who is his client at the time, and a divorcee – and she seems outraged and walks out on him; but then there is an immediate cut to them exiting a courthouse together after their low-key wedding. Apart from leaving out details that aren’t relevant to the film’s immediate purpose, this sudden cut is a reminder of Shahid’s persistence, and it also lets us conjecture what may have happened: perhaps Mariam – because of the conservative assumptions of the milieu she grew up in –was so taken aback by Shahid’s proposal that she simply didn’t know how to respond, and took some time to come around.

I liked the economy of the storytelling too: everything isn’t spelled out, the viewer is allowed to fill in the gaps, make leaps and connections. In the early scenes particularly, we get snapshots from Shahid’s life – appropriate perhaps for a story about a man whose life was cut short much too soon, who never got a chance to realise his full potential or do everything he wanted to do. There are small parts here – cameos, really – for Kay Kay Menon and Tigmanshu Dhulia as people Shahid meets on the course of his journey from naif to potential jihadi to believing that you can only change the system by being part of it. Watching the film, I kept getting the impression that a longer (more flabby, more didactic) cut exists; that (for example) Menon and Dhulia may have had larger roles, and that the director and editor showed discernment in paring the film down to its current length. In one scene, Shahid proposes to Mariam – who is his client at the time, and a divorcee – and she seems outraged and walks out on him; but then there is an immediate cut to them exiting a courthouse together after their low-key wedding. Apart from leaving out details that aren’t relevant to the film’s immediate purpose, this sudden cut is a reminder of Shahid’s persistence, and it also lets us conjecture what may have happened: perhaps Mariam – because of the conservative assumptions of the milieu she grew up in –was so taken aback by Shahid’s proposal that she simply didn’t know how to respond, and took some time to come around. In any case, the world of the lower-class Indian Muslim – under-educated, vulnerable to fear and paranoia, exploited by politicians as well as religious heads – is very much in the background of this film, even though the script doesn’t emphasise it. We never forget the social milieu Shahid hails from, and there are glimpses of cultural conflicts and inner turmoil, as in the scene where he takes his wife to meet his family for the first time and she is appalled that he is asking her to do something she has never done, to wear a burkha (“just this once, never again” he pleads, but in the desperation he shows, one can see where the “just this once” might lead in the future). Scenes like this make Shahid’s personal growth and self-actualisation even more creditable, because we are reminded of the many things he had to overcome, the many small battles he had to win. This isn’t a man to whom heroism comes naturally, he has to grow into it. And by the end, this intense, low-key film has us believing in him.

In any case, the world of the lower-class Indian Muslim – under-educated, vulnerable to fear and paranoia, exploited by politicians as well as religious heads – is very much in the background of this film, even though the script doesn’t emphasise it. We never forget the social milieu Shahid hails from, and there are glimpses of cultural conflicts and inner turmoil, as in the scene where he takes his wife to meet his family for the first time and she is appalled that he is asking her to do something she has never done, to wear a burkha (“just this once, never again” he pleads, but in the desperation he shows, one can see where the “just this once” might lead in the future). Scenes like this make Shahid’s personal growth and self-actualisation even more creditable, because we are reminded of the many things he had to overcome, the many small battles he had to win. This isn’t a man to whom heroism comes naturally, he has to grow into it. And by the end, this intense, low-key film has us believing in him.

Published on October 15, 2013 06:18

October 9, 2013

Smoke screens and jasmine blues

[Did a version of this for Business Standard]

I have mixed feelings about the anti-smoking ads that precede the main feature in movie halls. Mainly, they annoy me because they add to the already-considerable list of distractions before a movie begins: the line of trailers, Vinay Pathak swanning about in a bright red coat as he extols a bank’s interest rates. If you're punctual to a fault, and impatient to boot, these things can be exasperating. On the other hand, my sadistic side delights in the sound of pampered brats, insulated from the world beyond their velvety multiplex seats, groaning when the grislier ads play - the thought of people being faced with such images just before the glossy movie they have come to watch (and just as they are dipping into their gold-plated caramel-popcorn buckets) is a pleasing one.

I am clearer though about the idiocy of signs scrolling across the bottom of the screen while a film is playing. And as you probably know, the decision to turn every movie experience into a public-service advertisement hasn’t pleased Woody Allen either. His long association with absurdist comedy notwithstanding, the veteran director doesn’t see the funny side of “Cigarette smoking is injurious to health” signs besmirching his creations. Which means Indian viewers won’t see his new film Blue Jasmine on the big screen.

I am clearer though about the idiocy of signs scrolling across the bottom of the screen while a film is playing. And as you probably know, the decision to turn every movie experience into a public-service advertisement hasn’t pleased Woody Allen either. His long association with absurdist comedy notwithstanding, the veteran director doesn’t see the funny side of “Cigarette smoking is injurious to health” signs besmirching his creations. Which means Indian viewers won’t see his new film Blue Jasmine on the big screen.

Allen’s stand – and the equally firm one by the censor board to not make an exception for him – has revived old arguments about societal welfare versus the self-centred impulses of the ivory-tower artist. (The conversation has already headed off into predictable tangents too: on message-boards, people are pointing out that Allen – given the many controversies around his personal life – is not exactly an exemplar of public morality; so why should anyone listen to his whining about such things?) Central to such discussions is the stated purpose and obligation of art. As Orson Welles (or was it Alfred Hitchcock, or Shah Rukh Khan, or Lassie?) said once, “If I want to send a message, I’ll go to the post office.” That line sounds facetious, but the implication isn’t that films shouldn’t convey anything positive or affirming – it is that a “message” or “idea” can be delicately embedded within a narrative rather than ladled out for quick consumption; the viewer might be required to do some thinking of his own.

Of course, pedantry can sometimes serve a purpose too, especially in a society where a large number of people are under-educated and things occasionally need to be spelled out. But these anti-smoking tickers are context-free and indiscriminate, showing up with every glimpse of a cigarette (or bidi, or cigar). It doesn’t matter, for instance, that the sort of viewer who spends Rs 400 on Blue Jasmine is likely to be someone who already knows about the dangers of smoking (and possibly doesn’t care).

At times the ads are not just distracting or superfluous, but farcical. On two recent occasions I involuntarily snorted out loud when anti-cigarette warnings appeared on the screen. One was during Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained

, a film in which slaves undergo various forms of mistreatment (a few stolen moments with a pipe might be the closest some of these people come to achieving peace or grace) and pretty much every character is in danger of having his head blown off at any given point; arguably, rifles are a more pressing threat in this universe than cigarettes. Then there was the recent re-release of Mira Nair’s

Salaam Bombay

, a story about lives lived on the edge of the abyss, or on the edge of the railway tracks, with the junkie Chillum (Raghuvir Yadav) constantly on the verge of throwing himself in front of an approaching train. He is an addict (and he is leading the film’s protagonist down a similar path) but the real drug here, the thing that is most “injurious” to the characters’ health, is poverty and circumstance.

At times the ads are not just distracting or superfluous, but farcical. On two recent occasions I involuntarily snorted out loud when anti-cigarette warnings appeared on the screen. One was during Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained

, a film in which slaves undergo various forms of mistreatment (a few stolen moments with a pipe might be the closest some of these people come to achieving peace or grace) and pretty much every character is in danger of having his head blown off at any given point; arguably, rifles are a more pressing threat in this universe than cigarettes. Then there was the recent re-release of Mira Nair’s

Salaam Bombay

, a story about lives lived on the edge of the abyss, or on the edge of the railway tracks, with the junkie Chillum (Raghuvir Yadav) constantly on the verge of throwing himself in front of an approaching train. He is an addict (and he is leading the film’s protagonist down a similar path) but the real drug here, the thing that is most “injurious” to the characters’ health, is poverty and circumstance.

Given this, there was something morbidly funny about watching Salaam Bombay in the company of a privileged audience, with anti-tobacco riders playing almost throughout. But then good intentions and common sense don’t always go together. If a Marx Brothers film were ever shown in our halls, there would be a permanent warning at the bottom of the screen, given the cigar attached to Groucho’s lower lip. A Jaane bhi do Yaaro re-release would have a similar ticker with the scene where Ahuja sticks a cigarette between the (stone-cold-dead) DeMello’s lips. Perhaps Woody Allen – whose recent films have doubled as tourism guides to the major cities of the world – could make a Mumbai-based movie about all this, and call it Shadows and Smog.

Given this, there was something morbidly funny about watching Salaam Bombay in the company of a privileged audience, with anti-tobacco riders playing almost throughout. But then good intentions and common sense don’t always go together. If a Marx Brothers film were ever shown in our halls, there would be a permanent warning at the bottom of the screen, given the cigar attached to Groucho’s lower lip. A Jaane bhi do Yaaro re-release would have a similar ticker with the scene where Ahuja sticks a cigarette between the (stone-cold-dead) DeMello’s lips. Perhaps Woody Allen – whose recent films have doubled as tourism guides to the major cities of the world – could make a Mumbai-based movie about all this, and call it Shadows and Smog.

P.S. Anyway, as long as we insist on sticking messages on our big screens, why stop at tobacco? I propose the addition of the text “Feeding strangers may be injurious to emotional health” on prints of The Lunchbox.

I have mixed feelings about the anti-smoking ads that precede the main feature in movie halls. Mainly, they annoy me because they add to the already-considerable list of distractions before a movie begins: the line of trailers, Vinay Pathak swanning about in a bright red coat as he extols a bank’s interest rates. If you're punctual to a fault, and impatient to boot, these things can be exasperating. On the other hand, my sadistic side delights in the sound of pampered brats, insulated from the world beyond their velvety multiplex seats, groaning when the grislier ads play - the thought of people being faced with such images just before the glossy movie they have come to watch (and just as they are dipping into their gold-plated caramel-popcorn buckets) is a pleasing one.

I am clearer though about the idiocy of signs scrolling across the bottom of the screen while a film is playing. And as you probably know, the decision to turn every movie experience into a public-service advertisement hasn’t pleased Woody Allen either. His long association with absurdist comedy notwithstanding, the veteran director doesn’t see the funny side of “Cigarette smoking is injurious to health” signs besmirching his creations. Which means Indian viewers won’t see his new film Blue Jasmine on the big screen.

I am clearer though about the idiocy of signs scrolling across the bottom of the screen while a film is playing. And as you probably know, the decision to turn every movie experience into a public-service advertisement hasn’t pleased Woody Allen either. His long association with absurdist comedy notwithstanding, the veteran director doesn’t see the funny side of “Cigarette smoking is injurious to health” signs besmirching his creations. Which means Indian viewers won’t see his new film Blue Jasmine on the big screen.Allen’s stand – and the equally firm one by the censor board to not make an exception for him – has revived old arguments about societal welfare versus the self-centred impulses of the ivory-tower artist. (The conversation has already headed off into predictable tangents too: on message-boards, people are pointing out that Allen – given the many controversies around his personal life – is not exactly an exemplar of public morality; so why should anyone listen to his whining about such things?) Central to such discussions is the stated purpose and obligation of art. As Orson Welles (or was it Alfred Hitchcock, or Shah Rukh Khan, or Lassie?) said once, “If I want to send a message, I’ll go to the post office.” That line sounds facetious, but the implication isn’t that films shouldn’t convey anything positive or affirming – it is that a “message” or “idea” can be delicately embedded within a narrative rather than ladled out for quick consumption; the viewer might be required to do some thinking of his own.

Of course, pedantry can sometimes serve a purpose too, especially in a society where a large number of people are under-educated and things occasionally need to be spelled out. But these anti-smoking tickers are context-free and indiscriminate, showing up with every glimpse of a cigarette (or bidi, or cigar). It doesn’t matter, for instance, that the sort of viewer who spends Rs 400 on Blue Jasmine is likely to be someone who already knows about the dangers of smoking (and possibly doesn’t care).

At times the ads are not just distracting or superfluous, but farcical. On two recent occasions I involuntarily snorted out loud when anti-cigarette warnings appeared on the screen. One was during Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained

, a film in which slaves undergo various forms of mistreatment (a few stolen moments with a pipe might be the closest some of these people come to achieving peace or grace) and pretty much every character is in danger of having his head blown off at any given point; arguably, rifles are a more pressing threat in this universe than cigarettes. Then there was the recent re-release of Mira Nair’s

Salaam Bombay

, a story about lives lived on the edge of the abyss, or on the edge of the railway tracks, with the junkie Chillum (Raghuvir Yadav) constantly on the verge of throwing himself in front of an approaching train. He is an addict (and he is leading the film’s protagonist down a similar path) but the real drug here, the thing that is most “injurious” to the characters’ health, is poverty and circumstance.

At times the ads are not just distracting or superfluous, but farcical. On two recent occasions I involuntarily snorted out loud when anti-cigarette warnings appeared on the screen. One was during Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained

, a film in which slaves undergo various forms of mistreatment (a few stolen moments with a pipe might be the closest some of these people come to achieving peace or grace) and pretty much every character is in danger of having his head blown off at any given point; arguably, rifles are a more pressing threat in this universe than cigarettes. Then there was the recent re-release of Mira Nair’s

Salaam Bombay

, a story about lives lived on the edge of the abyss, or on the edge of the railway tracks, with the junkie Chillum (Raghuvir Yadav) constantly on the verge of throwing himself in front of an approaching train. He is an addict (and he is leading the film’s protagonist down a similar path) but the real drug here, the thing that is most “injurious” to the characters’ health, is poverty and circumstance. Given this, there was something morbidly funny about watching Salaam Bombay in the company of a privileged audience, with anti-tobacco riders playing almost throughout. But then good intentions and common sense don’t always go together. If a Marx Brothers film were ever shown in our halls, there would be a permanent warning at the bottom of the screen, given the cigar attached to Groucho’s lower lip. A Jaane bhi do Yaaro re-release would have a similar ticker with the scene where Ahuja sticks a cigarette between the (stone-cold-dead) DeMello’s lips. Perhaps Woody Allen – whose recent films have doubled as tourism guides to the major cities of the world – could make a Mumbai-based movie about all this, and call it Shadows and Smog.

Given this, there was something morbidly funny about watching Salaam Bombay in the company of a privileged audience, with anti-tobacco riders playing almost throughout. But then good intentions and common sense don’t always go together. If a Marx Brothers film were ever shown in our halls, there would be a permanent warning at the bottom of the screen, given the cigar attached to Groucho’s lower lip. A Jaane bhi do Yaaro re-release would have a similar ticker with the scene where Ahuja sticks a cigarette between the (stone-cold-dead) DeMello’s lips. Perhaps Woody Allen – whose recent films have doubled as tourism guides to the major cities of the world – could make a Mumbai-based movie about all this, and call it Shadows and Smog.P.S. Anyway, as long as we insist on sticking messages on our big screens, why stop at tobacco? I propose the addition of the text “Feeding strangers may be injurious to emotional health” on prints of The Lunchbox.

Published on October 09, 2013 20:44

October 3, 2013

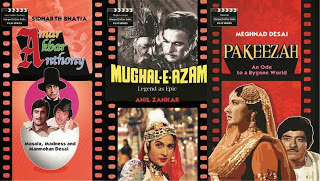

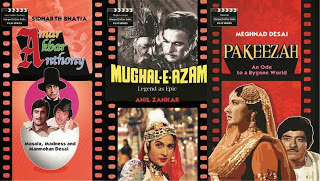

The film-book series contd: Mughal-e-Azam, Pakeezah, Amar Akbar Anthony

A shout-out for enthusiasts of film literature: the Harper Collins series of books about iconic Hindi films (which began in 2010 with these three titles, including my book on

Jaane bhi do Yaaro

) is in its second innings. Now in stores: Sidharth Bhatia’s

Amar Akbar Anthony: Masala, Madness and Manmohan Desai

, Anil Zankar’s

Mughal-e-Azam: Legend as Epic

, and Meghnad Desai’s

Pakeezah: An Ode to a Bygone Era

. The authors are all knowledgeable movie buffs, so there should be many good things within these pages. I’ll try to do a review once I have read the books.

Published on October 03, 2013 05:34

September 21, 2013

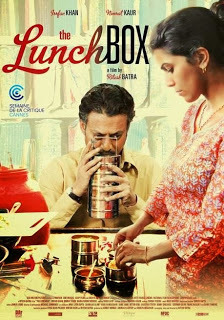

Visual storytelling in The Lunchbox

When making simple distinctions between types of cinema, we often think of “character-driven” stories (vis-à-vis “action-driven” stories) as being filled with conversation or monologues. Just last week, I wrote about a relationship film –

Shuddh Desi Romance

– that was all about talking and analysing; explaining things to others, to yourself, to the viewer. But one of the surprises – and eventually, for me, one of the great pleasures – of Ritesh Batra’s

The Lunchbox

was that some of its most effective moments relied on visual storytelling (or as the cliché has it, “pure cinema”), requiring special engagement on the viewer’s part over and above what is being said by the characters. In some scenes I felt almost like I was watching the sort of quietly elegant human comedy that Tati or Keaton did so well.

A marker of that visual engagement is an object, introduced at the start of the film: a tiffin lunch nestled in a green-and-white cover, which makes its way – via Mumbai’s famous dabba-wallahs – from a home to an office. As the dabba-wallahs take countless lunch-boxes through rush-hour traffic, our attention remains fixed on the distinct green-and-white bag, the sunlight dappling on it through the train’s windows. Then, less than 10 minutes into the film, come two wordless scenes that tell us the “plot” is underway. A middle-aged man named Fernandes (Irrfan Khan) unzips the green-white cover and starts to open the tiffin, but we see that something is off. What began as an almost unconscious action – something he mechanically does at exactly this time each day – becomes more deliberate; we can tell that the container he is opening is not the sort of container he is accustomed to handling. (This is a man whose life has been built around routine – he has been in the same job, in an insurance firm’s claims department, for 35 years – but now, confronted with newness, his eyes click into focus.) In the next scene, the container has been returned to the doorstep of a woman named Ila (Nimrat Kaur), and her movements as she picks up the bag are just as mechanical as Fernandes’s were, but then she hesitates, weighs the tiffin in her hand, realises that it is empty – clearly not an everyday occurrence. A look of cautious pleasure crosses her face.

A marker of that visual engagement is an object, introduced at the start of the film: a tiffin lunch nestled in a green-and-white cover, which makes its way – via Mumbai’s famous dabba-wallahs – from a home to an office. As the dabba-wallahs take countless lunch-boxes through rush-hour traffic, our attention remains fixed on the distinct green-and-white bag, the sunlight dappling on it through the train’s windows. Then, less than 10 minutes into the film, come two wordless scenes that tell us the “plot” is underway. A middle-aged man named Fernandes (Irrfan Khan) unzips the green-white cover and starts to open the tiffin, but we see that something is off. What began as an almost unconscious action – something he mechanically does at exactly this time each day – becomes more deliberate; we can tell that the container he is opening is not the sort of container he is accustomed to handling. (This is a man whose life has been built around routine – he has been in the same job, in an insurance firm’s claims department, for 35 years – but now, confronted with newness, his eyes click into focus.) In the next scene, the container has been returned to the doorstep of a woman named Ila (Nimrat Kaur), and her movements as she picks up the bag are just as mechanical as Fernandes’s were, but then she hesitates, weighs the tiffin in her hand, realises that it is empty – clearly not an everyday occurrence. A look of cautious pleasure crosses her face.

Not a word has been spoken in these two scenes, even the gestures aren’t especially pronounced, yet the attentive viewer can easily figure out what has happened. There has been a mistake in the delivery of a lunch box; Mr Fernandes has eaten the food meant for Ila’s husband; Ila, who is used to leftovers being sent back and noncommittal grunts of acknowledgement later in the evening, is happy that her cooking has been appreciated. These sequences are so fluid, so well constructed and performed, that we have no trouble accepting the basic premise (even given the widely circulated statistics about the efficiency of the dabba-wallahs) or what follows: Ila discovers the mix-up but sends Fernandes lunch again, along with a letter (“Thank you bannta hai na,” she tells her confidante, an old neighbour) – and then, in the email age, these two people who know nothing about each other begin an unlikely correspondence by dabba.

Not a word has been spoken in these two scenes, even the gestures aren’t especially pronounced, yet the attentive viewer can easily figure out what has happened. There has been a mistake in the delivery of a lunch box; Mr Fernandes has eaten the food meant for Ila’s husband; Ila, who is used to leftovers being sent back and noncommittal grunts of acknowledgement later in the evening, is happy that her cooking has been appreciated. These sequences are so fluid, so well constructed and performed, that we have no trouble accepting the basic premise (even given the widely circulated statistics about the efficiency of the dabba-wallahs) or what follows: Ila discovers the mix-up but sends Fernandes lunch again, along with a letter (“Thank you bannta hai na,” she tells her confidante, an old neighbour) – and then, in the email age, these two people who know nothing about each other begin an unlikely correspondence by dabba.

Understatement in cinema can be a tricky thing. Get it wrong and you’re in danger of not just making the film flat and uninvolving, but also appearing just as self-conscious and forced as the “over-doer”. (As Orson Welles once put it, “Ham actors are not all of them strutters and fretters, theatrical vocalizers – a lot of them are understaters, flashing winsome little smiles over the teacups, or scratching their T-shirts.”) The Lunchbox gets understatement and restraint exactly right, both in the outstanding lead performances by Khan and Kaur as the lonely-hearts and in Batra’s delicate screenplay, which makes expert use of the “show, don’t tell” principle. The viewer is constantly invited to participate in this story, to work things out as layers are slowly peeled away. When Fernandes goes to the little restaurant that sends him his lunch – to tell them he is retiring next month, he won’t need the dabbas any more – we can make out a blurred mass of familiar green-and-white container-bags in the window (they are visible but not obtrusive) and it helps us understand how the mix-up might have happened. Later, hearing about a woman who jumped off a building with her daughter, he fears it might be Ila, and we feel his tension in the subsequent scene where he is seated at his office desk around lunch hour and the dabba-wallah does the rounds in the background, apparently bypassing Fernandes’s desk and moving away (while Fernandes cranes his neck anxiously) before returning and setting down the comforting green-white package. Purposeful silences and long pauses in films can be gimmicky (and sometimes, a film that is celebrated for “requiring the viewer to be patient” is really a film that requires a viewer to be bored), but here the writing and the acting reveals character, facilitates full engagement and lets the viewer use the silences to figure out what is happening, what someone is thinking, what may be coming next.

outstanding lead performances by Khan and Kaur as the lonely-hearts and in Batra’s delicate screenplay, which makes expert use of the “show, don’t tell” principle. The viewer is constantly invited to participate in this story, to work things out as layers are slowly peeled away. When Fernandes goes to the little restaurant that sends him his lunch – to tell them he is retiring next month, he won’t need the dabbas any more – we can make out a blurred mass of familiar green-and-white container-bags in the window (they are visible but not obtrusive) and it helps us understand how the mix-up might have happened. Later, hearing about a woman who jumped off a building with her daughter, he fears it might be Ila, and we feel his tension in the subsequent scene where he is seated at his office desk around lunch hour and the dabba-wallah does the rounds in the background, apparently bypassing Fernandes’s desk and moving away (while Fernandes cranes his neck anxiously) before returning and setting down the comforting green-white package. Purposeful silences and long pauses in films can be gimmicky (and sometimes, a film that is celebrated for “requiring the viewer to be patient” is really a film that requires a viewer to be bored), but here the writing and the acting reveals character, facilitates full engagement and lets the viewer use the silences to figure out what is happening, what someone is thinking, what may be coming next.

There are so many other subtle touches, from a glimpse of a bathroom mirror that has rarely needed to be wiped clean, to the gamut of expressions on Ila’s face when she doesn’t see a letter in the tiffin but then finds it under a roti, or a scene where a phone is answered off-screen and we need to hear only a couple of words, spoken in a hurried, matter-of-fact tone, to gather that the speaker’s father has died and that she barely has time to sob a little to herself while preparing to leave for the crematorium. I also liked the way in which Fernandes’s first name is revealed to us more than halfway through the film, and how the construction of that sequence ties in with another theme – nostalgia for a distant past, felt by people who have aged without realising it. (This IS made explicit in the screenplay at one point, when Fernandes talks about why he suddenly felt the need to watch episodes of his deceased wife’s favourite old TV show, Yeh jo Hai Zindagi. But when Ila asks to play the songs of a romantic film from 20 years ago, one might guess that it is not just an expression of her current feelings but also a brief return to a childhood when her life was simpler and happier.)

This is a story about people connected in tenuous ways: by a dabba-wallah’s mistake, by shouted conversation across the walls of an old building, by a basket lowered outside the window of a flat to the one below. (Though one of the key characters, Ila’s old “aunty”, is never seen – she is just a disembodied voice – we feel we know her well.) There

This is a story about people connected in tenuous ways: by a dabba-wallah’s mistake, by shouted conversation across the walls of an old building, by a basket lowered outside the window of a flat to the one below. (Though one of the key characters, Ila’s old “aunty”, is never seen – she is just a disembodied voice – we feel we know her well.) There

are visual links between the two protagonists too: one person’s

voiceover seems to comment on the other’s actions, and there are echoing

gestures, including mundane ones like waving flies away from food;

reminders that many of the quotidian details of Ila's and Fernandes's

lives are similar. They feel similarly isolated and “rocked back and

forth by life” (as Fernandes puts it in a letter, while the visuals

shows him sitting in a juddering local train), and they unrealistically

dream of moving together to a land where gross national happiness is the stock in trade. But there is of course the possibility that they will remain ultimately cut off, like ships passing in the night, or like the two trains in the film's opening shot, moving towards each other slowly on parallel tracks, so near and yet so distant. And given these various possibilities, as well as the delicacy of the film’s structure, I thought the open-endedness of its conclusion was just right. As so much else is.

A marker of that visual engagement is an object, introduced at the start of the film: a tiffin lunch nestled in a green-and-white cover, which makes its way – via Mumbai’s famous dabba-wallahs – from a home to an office. As the dabba-wallahs take countless lunch-boxes through rush-hour traffic, our attention remains fixed on the distinct green-and-white bag, the sunlight dappling on it through the train’s windows. Then, less than 10 minutes into the film, come two wordless scenes that tell us the “plot” is underway. A middle-aged man named Fernandes (Irrfan Khan) unzips the green-white cover and starts to open the tiffin, but we see that something is off. What began as an almost unconscious action – something he mechanically does at exactly this time each day – becomes more deliberate; we can tell that the container he is opening is not the sort of container he is accustomed to handling. (This is a man whose life has been built around routine – he has been in the same job, in an insurance firm’s claims department, for 35 years – but now, confronted with newness, his eyes click into focus.) In the next scene, the container has been returned to the doorstep of a woman named Ila (Nimrat Kaur), and her movements as she picks up the bag are just as mechanical as Fernandes’s were, but then she hesitates, weighs the tiffin in her hand, realises that it is empty – clearly not an everyday occurrence. A look of cautious pleasure crosses her face.

A marker of that visual engagement is an object, introduced at the start of the film: a tiffin lunch nestled in a green-and-white cover, which makes its way – via Mumbai’s famous dabba-wallahs – from a home to an office. As the dabba-wallahs take countless lunch-boxes through rush-hour traffic, our attention remains fixed on the distinct green-and-white bag, the sunlight dappling on it through the train’s windows. Then, less than 10 minutes into the film, come two wordless scenes that tell us the “plot” is underway. A middle-aged man named Fernandes (Irrfan Khan) unzips the green-white cover and starts to open the tiffin, but we see that something is off. What began as an almost unconscious action – something he mechanically does at exactly this time each day – becomes more deliberate; we can tell that the container he is opening is not the sort of container he is accustomed to handling. (This is a man whose life has been built around routine – he has been in the same job, in an insurance firm’s claims department, for 35 years – but now, confronted with newness, his eyes click into focus.) In the next scene, the container has been returned to the doorstep of a woman named Ila (Nimrat Kaur), and her movements as she picks up the bag are just as mechanical as Fernandes’s were, but then she hesitates, weighs the tiffin in her hand, realises that it is empty – clearly not an everyday occurrence. A look of cautious pleasure crosses her face. Not a word has been spoken in these two scenes, even the gestures aren’t especially pronounced, yet the attentive viewer can easily figure out what has happened. There has been a mistake in the delivery of a lunch box; Mr Fernandes has eaten the food meant for Ila’s husband; Ila, who is used to leftovers being sent back and noncommittal grunts of acknowledgement later in the evening, is happy that her cooking has been appreciated. These sequences are so fluid, so well constructed and performed, that we have no trouble accepting the basic premise (even given the widely circulated statistics about the efficiency of the dabba-wallahs) or what follows: Ila discovers the mix-up but sends Fernandes lunch again, along with a letter (“Thank you bannta hai na,” she tells her confidante, an old neighbour) – and then, in the email age, these two people who know nothing about each other begin an unlikely correspondence by dabba.

Not a word has been spoken in these two scenes, even the gestures aren’t especially pronounced, yet the attentive viewer can easily figure out what has happened. There has been a mistake in the delivery of a lunch box; Mr Fernandes has eaten the food meant for Ila’s husband; Ila, who is used to leftovers being sent back and noncommittal grunts of acknowledgement later in the evening, is happy that her cooking has been appreciated. These sequences are so fluid, so well constructed and performed, that we have no trouble accepting the basic premise (even given the widely circulated statistics about the efficiency of the dabba-wallahs) or what follows: Ila discovers the mix-up but sends Fernandes lunch again, along with a letter (“Thank you bannta hai na,” she tells her confidante, an old neighbour) – and then, in the email age, these two people who know nothing about each other begin an unlikely correspondence by dabba.Understatement in cinema can be a tricky thing. Get it wrong and you’re in danger of not just making the film flat and uninvolving, but also appearing just as self-conscious and forced as the “over-doer”. (As Orson Welles once put it, “Ham actors are not all of them strutters and fretters, theatrical vocalizers – a lot of them are understaters, flashing winsome little smiles over the teacups, or scratching their T-shirts.”) The Lunchbox gets understatement and restraint exactly right, both in the

outstanding lead performances by Khan and Kaur as the lonely-hearts and in Batra’s delicate screenplay, which makes expert use of the “show, don’t tell” principle. The viewer is constantly invited to participate in this story, to work things out as layers are slowly peeled away. When Fernandes goes to the little restaurant that sends him his lunch – to tell them he is retiring next month, he won’t need the dabbas any more – we can make out a blurred mass of familiar green-and-white container-bags in the window (they are visible but not obtrusive) and it helps us understand how the mix-up might have happened. Later, hearing about a woman who jumped off a building with her daughter, he fears it might be Ila, and we feel his tension in the subsequent scene where he is seated at his office desk around lunch hour and the dabba-wallah does the rounds in the background, apparently bypassing Fernandes’s desk and moving away (while Fernandes cranes his neck anxiously) before returning and setting down the comforting green-white package. Purposeful silences and long pauses in films can be gimmicky (and sometimes, a film that is celebrated for “requiring the viewer to be patient” is really a film that requires a viewer to be bored), but here the writing and the acting reveals character, facilitates full engagement and lets the viewer use the silences to figure out what is happening, what someone is thinking, what may be coming next.

outstanding lead performances by Khan and Kaur as the lonely-hearts and in Batra’s delicate screenplay, which makes expert use of the “show, don’t tell” principle. The viewer is constantly invited to participate in this story, to work things out as layers are slowly peeled away. When Fernandes goes to the little restaurant that sends him his lunch – to tell them he is retiring next month, he won’t need the dabbas any more – we can make out a blurred mass of familiar green-and-white container-bags in the window (they are visible but not obtrusive) and it helps us understand how the mix-up might have happened. Later, hearing about a woman who jumped off a building with her daughter, he fears it might be Ila, and we feel his tension in the subsequent scene where he is seated at his office desk around lunch hour and the dabba-wallah does the rounds in the background, apparently bypassing Fernandes’s desk and moving away (while Fernandes cranes his neck anxiously) before returning and setting down the comforting green-white package. Purposeful silences and long pauses in films can be gimmicky (and sometimes, a film that is celebrated for “requiring the viewer to be patient” is really a film that requires a viewer to be bored), but here the writing and the acting reveals character, facilitates full engagement and lets the viewer use the silences to figure out what is happening, what someone is thinking, what may be coming next. There are so many other subtle touches, from a glimpse of a bathroom mirror that has rarely needed to be wiped clean, to the gamut of expressions on Ila’s face when she doesn’t see a letter in the tiffin but then finds it under a roti, or a scene where a phone is answered off-screen and we need to hear only a couple of words, spoken in a hurried, matter-of-fact tone, to gather that the speaker’s father has died and that she barely has time to sob a little to herself while preparing to leave for the crematorium. I also liked the way in which Fernandes’s first name is revealed to us more than halfway through the film, and how the construction of that sequence ties in with another theme – nostalgia for a distant past, felt by people who have aged without realising it. (This IS made explicit in the screenplay at one point, when Fernandes talks about why he suddenly felt the need to watch episodes of his deceased wife’s favourite old TV show, Yeh jo Hai Zindagi. But when Ila asks to play the songs of a romantic film from 20 years ago, one might guess that it is not just an expression of her current feelings but also a brief return to a childhood when her life was simpler and happier.)

This is a story about people connected in tenuous ways: by a dabba-wallah’s mistake, by shouted conversation across the walls of an old building, by a basket lowered outside the window of a flat to the one below. (Though one of the key characters, Ila’s old “aunty”, is never seen – she is just a disembodied voice – we feel we know her well.) There

This is a story about people connected in tenuous ways: by a dabba-wallah’s mistake, by shouted conversation across the walls of an old building, by a basket lowered outside the window of a flat to the one below. (Though one of the key characters, Ila’s old “aunty”, is never seen – she is just a disembodied voice – we feel we know her well.) There are visual links between the two protagonists too: one person’s

voiceover seems to comment on the other’s actions, and there are echoing

gestures, including mundane ones like waving flies away from food;

reminders that many of the quotidian details of Ila's and Fernandes's

lives are similar. They feel similarly isolated and “rocked back and

forth by life” (as Fernandes puts it in a letter, while the visuals

shows him sitting in a juddering local train), and they unrealistically

dream of moving together to a land where gross national happiness is the stock in trade. But there is of course the possibility that they will remain ultimately cut off, like ships passing in the night, or like the two trains in the film's opening shot, moving towards each other slowly on parallel tracks, so near and yet so distant. And given these various possibilities, as well as the delicacy of the film’s structure, I thought the open-endedness of its conclusion was just right. As so much else is.

Published on September 21, 2013 00:58

September 15, 2013

The bekaar in the big city: on Bimal Roy’s Naukri

Parts of Bimal Roy’s 1954 film

Naukri

reminded me of two great scenes from films made in the silent era’s last days: the opening sequence of King Vidor’s The Crowd, with people and vehicles thronging the streets of New York and the rapt camera gliding up the side of a skyscraper, then moving in to reveal countless worker ants at their desks (see video below); and the equally kinetic shot in F W Murnau’s Sunrise where two town-dwellers, the Man and the Wife, get their first view of the approaching city through the windows of their tram. The couple, sullen, distrustful and occupying separate spaces in the vehicle (understandable enough given that one of them has recently plotted to murder the other!), must now huddle together as they dodge traffic and find walking space on the footpaths: this new place is so overwhelming that it unites them.

As Naukri’s title credits end, the camera cranes up to gawk at a tall building, presumably with offices and employment opportunities in it – an apt image for a film about the big city as a place of opportunity and terror. In fact, the protagonist Ratan (Kishore Kumar) will make two long journeys over the course of the story: first from his village to Calcutta, and later to the much more distant Bombay, where he will have to contend with people speaking to him in unfamiliar tongues (Marathi, Parsi). His horizons broaden, but he also becomes more isolated (though the film has a deus ex machina in reserve for him).

As Naukri’s title credits end, the camera cranes up to gawk at a tall building, presumably with offices and employment opportunities in it – an apt image for a film about the big city as a place of opportunity and terror. In fact, the protagonist Ratan (Kishore Kumar) will make two long journeys over the course of the story: first from his village to Calcutta, and later to the much more distant Bombay, where he will have to contend with people speaking to him in unfamiliar tongues (Marathi, Parsi). His horizons broaden, but he also becomes more isolated (though the film has a deus ex machina in reserve for him).

Naukri contains many things we now think of as clichés of a cinematic past (whether they were clichés in 1954 is another question): the beloved sister suffering from TB, the widowed mother, the sanguine young man convinced that he will soon get a good job (he is BA Pass with distinction, after all) and overturn his family’s fortunes, the arrival of a letter bearing exam results, the arduous journey that begins with tearful farewells and a bullock-cart ride to the railway station. But these were understandable concerns of the “social” cinema of the post-Independence decade, when so many films were about young people from modest backgrounds entering a new world and taking the tide at its flood, or becoming corrupted or cynical.

Naukri contains many things we now think of as clichés of a cinematic past (whether they were clichés in 1954 is another question): the beloved sister suffering from TB, the widowed mother, the sanguine young man convinced that he will soon get a good job (he is BA Pass with distinction, after all) and overturn his family’s fortunes, the arrival of a letter bearing exam results, the arduous journey that begins with tearful farewells and a bullock-cart ride to the railway station. But these were understandable concerns of the “social” cinema of the post-Independence decade, when so many films were about young people from modest backgrounds entering a new world and taking the tide at its flood, or becoming corrupted or cynical.

Ratan’s fantasy (expressed in the film’s first song “Chhota sa Ghar Hoga”) of having a small house under the clouds, with his sister sitting on a silver chair and his mother on a golden throne, turns out to be nearly as unworkable as little Sujata’s dream – in one of Roy’s best films – of visiting a magical kingdom. Arriving in Calcutta, he is disappointed because the job he thought was his has gone to someone else. Things are far from dire at this point – more chances will presumably come along soon, and meanwhile he is boarding in a small hotel with a genial group of other young men – and yet, for all his optimism, we are warned: past the twilight hour, the “Bekaari block” he is living in resembles a perdition where men who have been unemployed for months play cards, bicker, gossip, vent frustrations late into the night. One of them, clearly a terrible singer, does his riyaaz, and though the scene can be viewed in comic terms it has a dark side – the man is like a ghoul shrieking into the void.

magical kingdom. Arriving in Calcutta, he is disappointed because the job he thought was his has gone to someone else. Things are far from dire at this point – more chances will presumably come along soon, and meanwhile he is boarding in a small hotel with a genial group of other young men – and yet, for all his optimism, we are warned: past the twilight hour, the “Bekaari block” he is living in resembles a perdition where men who have been unemployed for months play cards, bicker, gossip, vent frustrations late into the night. One of them, clearly a terrible singer, does his riyaaz, and though the scene can be viewed in comic terms it has a dark side – the man is like a ghoul shrieking into the void.

I was intrigued by the way Naukri moved between documentary-like neo-realism and the more dramatic tropes of mainstream storytelling: this is very much a scripted, incident-driven story (with some nice use of songs - I especially like this one, with the young Iftekhar singing "Main collector na banu aur na banunga officer...apna babu hi bana lo mukhe, bekaar hoon main"), but there is also plenty of location shooting, including shots of Kishore Kumar clinging to crowded buses and negotiating the madness of south Bombay during rush hour – scenes that have a slice-of-life quality to them. For all these points of interest though, this is a patchy film. It's easy to engage with at a basic level: that is more or less assured by Kumar’s likeable presence in nearly every scene, and the fluid storytelling abilities of Roy and his talented crew (Nabendu Ghosh, Salil Choudhury, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Asit Sen among them). But I was often unsure what mood it was reaching for.

For all these points of interest though, this is a patchy film. It's easy to engage with at a basic level: that is more or less assured by Kumar’s likeable presence in nearly every scene, and the fluid storytelling abilities of Roy and his talented crew (Nabendu Ghosh, Salil Choudhury, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Asit Sen among them). But I was often unsure what mood it was reaching for.

Ratan is determinedly cheery to begin with (his philosophy of life is that he must keep smiling and hoping, because if he looks at his predicament too closely he might sink into permanent despair) – so much so that when a genuine tragedy occurs relatively early in the film, it is glossed over, to jarring effect. He recovers too quickly, gets back to his jovial ways and begins a romance with a girl (Sheila Ramani) in the “saamne waali khidki”. (A parallel is established between the young man’s search for “naukri” and “ladki”– it is clear that he needs a job if he is ever to become a householder, or even a responsible boyfriend.) But then, in film’s the final section, since a dramatic climax has to somehow be reached, misfortune atop misfortune piles up to the point where there seems no option other than a suicide attempt at the railway tracks.

This creates structural unevenness, and a related problem is that it requires the story to keep manufacturing hurdles for Ratan, which is sometimes done in ham-handed ways. At one point he writes a letter to his girlfriend, telling her he has to go to Bombay for a job, and foolishly attaches his appointment letter with it, without making a copy or even bothering to memorise or note down the company name and address. Of course, the letter falls into the hands of the girl’s irate father, who feeds it to the kitchen stove after giving it barely a glance. The intention here is to make us feel concerned about Ratan’s fate, but instead one feels like smacking him and saying “You idiot, what were you thinking?” (Given his pride about having passed with distinction, I was reminded of the Peter Medawar quote about the spread of secondary and tertiary education creating a population of people “who have been educated far beyond their capacity to undertake analytical thought”.) The situation also leads to an incongruous bit of slapstick comedy where Ratan has to work out what the long and convoluted name of the company is.

This creates structural unevenness, and a related problem is that it requires the story to keep manufacturing hurdles for Ratan, which is sometimes done in ham-handed ways. At one point he writes a letter to his girlfriend, telling her he has to go to Bombay for a job, and foolishly attaches his appointment letter with it, without making a copy or even bothering to memorise or note down the company name and address. Of course, the letter falls into the hands of the girl’s irate father, who feeds it to the kitchen stove after giving it barely a glance. The intention here is to make us feel concerned about Ratan’s fate, but instead one feels like smacking him and saying “You idiot, what were you thinking?” (Given his pride about having passed with distinction, I was reminded of the Peter Medawar quote about the spread of secondary and tertiary education creating a population of people “who have been educated far beyond their capacity to undertake analytical thought”.) The situation also leads to an incongruous bit of slapstick comedy where Ratan has to work out what the long and convoluted name of the company is.

The stories that Bimal Roy used for his more reformist cinema lent themselves to a certain degree of didacticism anyway, but here a facile tone in some of the early scenes makes way for an excessively solemn one towards the end, and that mix didn’t really work for me. Other Roy films in a similar socially conscious vein – Sujata and Parakh, notably – do a better job of establishing a pitch and sticking with it. Naukri is still an engaging movie, but by the time we arrive at the solemn voiceover at the end, beseeching the viewer (apparently) to provide jobs to deserving young men, one can’t help feeling that Ratan’s misfortunes stem more from his own incompetence than from societal unfairness. I have read approving comments about Kishore Kumar playing a "serious role for once" in this film, compared to the "buffoons" he played elsewhere – but I think some of those intentionally comic characters would have handled certain situations more efficiently than poor Ratan does.

[Here's an earlier post about another film that combines documentary-like footage with dramatic storytelling, Jules Dassin's The Naked City]

As Naukri’s title credits end, the camera cranes up to gawk at a tall building, presumably with offices and employment opportunities in it – an apt image for a film about the big city as a place of opportunity and terror. In fact, the protagonist Ratan (Kishore Kumar) will make two long journeys over the course of the story: first from his village to Calcutta, and later to the much more distant Bombay, where he will have to contend with people speaking to him in unfamiliar tongues (Marathi, Parsi). His horizons broaden, but he also becomes more isolated (though the film has a deus ex machina in reserve for him).