Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 78

May 16, 2013

Phantoms in tunnels, and the quiet creepiness of the first Hannibal Lecter film

Being increasingly stressed out by road travel, I have had much reason to be grateful for the Delhi Metro in the last few years. But one of the more oddball benefits of the underground line involves a personal fetish, which I will hesitantly reveal here: I like watching the glow of an approaching train.

Not the train itself, mind, but the intangible things that herald its approach. This is roughly how it goes. Standing on the platform, staring into the darkness of the tunnel, you first have the vaguest sensation of light molecules shifting in the far distance, so that you’re unsure you can trust your eyes (and often, it does turn out to be an optical illusion). Then, very slowly, the sides of the tunnel light up, the specific effect depending on the degree of curvature of the route leading into the platform; in some stations you can see the train head-on from a long way off, and that’s no fun. Eventually this phantom light resolves itself into something concrete, the shadow of the train glides along the wall before the big worm itself appears, no longer scary now that it has a clear physical shape. But for those few seconds before it comes into view, there is a tantalising little Plato’s Cave effect where you can give your imagination full rein: what is there? What is coming? (Yes, I know, the more literal-minded of you might say: “It’s a TRAIN, you moron!” But indulge me.)

Here’s why I’m going on about this: I sometimes experience real-world situations as echoes of spooky moments from thrillers or horror films (at times this can be the only way to get through the drudgery that is real life), and the glow in the tunnel evokes the effect of a scene from Michael Mann’s 1986 film

Manhunter

. It’s been a long time since I watched this stylish thriller, but I thought of it when I heard about the new TV series

Hannibal

, about that most famous of fictional gentleman cannibals, Hannibal Lecter. Lecter is best known to movie-goers for his appearance in The Silence of the Lambs (and its cash-in-on-the-publicity sequels, where Anthony Hopkins reprised the role that got him an Oscar), but his first movie appearance was a 10-minute part in Manhunter, an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s superb thriller Red Dragon. Another British actor, Brian Cox, played the role, and the film – like the TV series – touched on Lecter’s complex relationship with detective Will Graham, who apprehended him.

Here’s why I’m going on about this: I sometimes experience real-world situations as echoes of spooky moments from thrillers or horror films (at times this can be the only way to get through the drudgery that is real life), and the glow in the tunnel evokes the effect of a scene from Michael Mann’s 1986 film

Manhunter

. It’s been a long time since I watched this stylish thriller, but I thought of it when I heard about the new TV series

Hannibal

, about that most famous of fictional gentleman cannibals, Hannibal Lecter. Lecter is best known to movie-goers for his appearance in The Silence of the Lambs (and its cash-in-on-the-publicity sequels, where Anthony Hopkins reprised the role that got him an Oscar), but his first movie appearance was a 10-minute part in Manhunter, an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s superb thriller Red Dragon. Another British actor, Brian Cox, played the role, and the film – like the TV series – touched on Lecter’s complex relationship with detective Will Graham, who apprehended him.

Anyway, the Manhunter scene that I relive in Metro stations begins with a security guard in an underground parking lot, reading the newspaper. Hearing a sound in the far distance, he peers around at the slanting, covered path that cars take to reach the parking base: nothing there, so he gets back to the paper. But the noise – a deep roaring, along with the sound of something rolling along – persists and grows. The camera cuts to the curved path and we see an orange glow lighting up the wall. The guard turns back again, this time a look of terror crosses his face as he leaps up from his chair and runs away; cut back, and at last we get the morbid payoff: a burning figure in a wheelchair heading straight at the camera, at us. (If you’ve been watching the film in sequence, you will know that the character in the wheelchair is a pesky tabloid reporter who had the poor luck to fall into the hands of a serial killer called the Red Dragon.)

It’s worth mentioning that the scene is brightly lit, and it may even be daylight outside the parking lot – the sense of unfathomable evil created here, as elsewhere in Manhunter, has nothing to do with dark shadows or what we think of as the regular trappings of horror cinema. This is a classic example of a film that achieves very menacing effects by keeping explicit detail to a minimum. In Harris’s book, we are told in a single terse sentence that the killer bites off the captive reporter’s lips. The visualisation of this moment in the film is even more restrained – no blood or gore, just an accumulation of little things: the Dragon with his back to the camera casually putting on a new set of teeth, telling the reporter they must seal their deal with a kiss, slowly bending his face towards him; cut to the exterior of the house, with birds calling across the night sky, perhaps implying the lipless screaming that is going on within.

It’s worth mentioning that the scene is brightly lit, and it may even be daylight outside the parking lot – the sense of unfathomable evil created here, as elsewhere in Manhunter, has nothing to do with dark shadows or what we think of as the regular trappings of horror cinema. This is a classic example of a film that achieves very menacing effects by keeping explicit detail to a minimum. In Harris’s book, we are told in a single terse sentence that the killer bites off the captive reporter’s lips. The visualisation of this moment in the film is even more restrained – no blood or gore, just an accumulation of little things: the Dragon with his back to the camera casually putting on a new set of teeth, telling the reporter they must seal their deal with a kiss, slowly bending his face towards him; cut to the exterior of the house, with birds calling across the night sky, perhaps implying the lipless screaming that is going on within.

In fact, some of the scariest scenes in the film are almost unnaturally bright, and the refusal to overuse genre conventions is reflected in the art design in the Hannibal Lecter scenes, which contrast strongly with the ones in The Silence of the Lambs. The later film showed Lecter incarcerated in a gloomy, dungeon-like prison cell that looked like it might have rats scuffling about and a private uncovered sewer running down the corridor outside, while Manhunter has him in a neat, blindingly white room where you could almost smell the anti-septic (I kept feeling that the doctor had a generous dose of Brylcreem in his hair!).

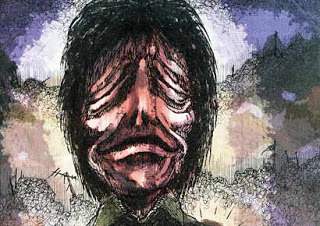

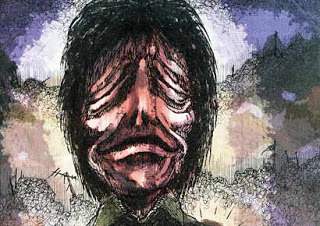

But the sterile tidiness of the setting only enhances the creepiness of these scenes: Lecter’s most distinct qualities – his old-world courtliness, his ability to look deep into the hearts and minds of others, and to manipulate their emotions – are very much on view. Visiting him in his cell, Will Graham is confronted with the terrifying knowledge that he has a deeply psychological connection with the man sitting before him, and that he might easily become a monster by wrestling with monsters. When Graham dashes out of the building after their meeting – even though the only demon pursuing him is the one inside his own mind – you can almost hear his heart pounding. And your own too. If the TV series comes close to replicating the insidiously scary quality of this film, it should be worth watching.

But the sterile tidiness of the setting only enhances the creepiness of these scenes: Lecter’s most distinct qualities – his old-world courtliness, his ability to look deep into the hearts and minds of others, and to manipulate their emotions – are very much on view. Visiting him in his cell, Will Graham is confronted with the terrifying knowledge that he has a deeply psychological connection with the man sitting before him, and that he might easily become a monster by wrestling with monsters. When Graham dashes out of the building after their meeting – even though the only demon pursuing him is the one inside his own mind – you can almost hear his heart pounding. And your own too. If the TV series comes close to replicating the insidiously scary quality of this film, it should be worth watching.

[Did a version of this for my DNA column. More thoughts on horror movies infecting the real world in my essay "Monsters I Have Known". And earlier posts on Thomas Harris and Hannibal Lecter here, here and here.]

Not the train itself, mind, but the intangible things that herald its approach. This is roughly how it goes. Standing on the platform, staring into the darkness of the tunnel, you first have the vaguest sensation of light molecules shifting in the far distance, so that you’re unsure you can trust your eyes (and often, it does turn out to be an optical illusion). Then, very slowly, the sides of the tunnel light up, the specific effect depending on the degree of curvature of the route leading into the platform; in some stations you can see the train head-on from a long way off, and that’s no fun. Eventually this phantom light resolves itself into something concrete, the shadow of the train glides along the wall before the big worm itself appears, no longer scary now that it has a clear physical shape. But for those few seconds before it comes into view, there is a tantalising little Plato’s Cave effect where you can give your imagination full rein: what is there? What is coming? (Yes, I know, the more literal-minded of you might say: “It’s a TRAIN, you moron!” But indulge me.)

Here’s why I’m going on about this: I sometimes experience real-world situations as echoes of spooky moments from thrillers or horror films (at times this can be the only way to get through the drudgery that is real life), and the glow in the tunnel evokes the effect of a scene from Michael Mann’s 1986 film

Manhunter

. It’s been a long time since I watched this stylish thriller, but I thought of it when I heard about the new TV series

Hannibal

, about that most famous of fictional gentleman cannibals, Hannibal Lecter. Lecter is best known to movie-goers for his appearance in The Silence of the Lambs (and its cash-in-on-the-publicity sequels, where Anthony Hopkins reprised the role that got him an Oscar), but his first movie appearance was a 10-minute part in Manhunter, an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s superb thriller Red Dragon. Another British actor, Brian Cox, played the role, and the film – like the TV series – touched on Lecter’s complex relationship with detective Will Graham, who apprehended him.

Here’s why I’m going on about this: I sometimes experience real-world situations as echoes of spooky moments from thrillers or horror films (at times this can be the only way to get through the drudgery that is real life), and the glow in the tunnel evokes the effect of a scene from Michael Mann’s 1986 film

Manhunter

. It’s been a long time since I watched this stylish thriller, but I thought of it when I heard about the new TV series

Hannibal

, about that most famous of fictional gentleman cannibals, Hannibal Lecter. Lecter is best known to movie-goers for his appearance in The Silence of the Lambs (and its cash-in-on-the-publicity sequels, where Anthony Hopkins reprised the role that got him an Oscar), but his first movie appearance was a 10-minute part in Manhunter, an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s superb thriller Red Dragon. Another British actor, Brian Cox, played the role, and the film – like the TV series – touched on Lecter’s complex relationship with detective Will Graham, who apprehended him.Anyway, the Manhunter scene that I relive in Metro stations begins with a security guard in an underground parking lot, reading the newspaper. Hearing a sound in the far distance, he peers around at the slanting, covered path that cars take to reach the parking base: nothing there, so he gets back to the paper. But the noise – a deep roaring, along with the sound of something rolling along – persists and grows. The camera cuts to the curved path and we see an orange glow lighting up the wall. The guard turns back again, this time a look of terror crosses his face as he leaps up from his chair and runs away; cut back, and at last we get the morbid payoff: a burning figure in a wheelchair heading straight at the camera, at us. (If you’ve been watching the film in sequence, you will know that the character in the wheelchair is a pesky tabloid reporter who had the poor luck to fall into the hands of a serial killer called the Red Dragon.)

It’s worth mentioning that the scene is brightly lit, and it may even be daylight outside the parking lot – the sense of unfathomable evil created here, as elsewhere in Manhunter, has nothing to do with dark shadows or what we think of as the regular trappings of horror cinema. This is a classic example of a film that achieves very menacing effects by keeping explicit detail to a minimum. In Harris’s book, we are told in a single terse sentence that the killer bites off the captive reporter’s lips. The visualisation of this moment in the film is even more restrained – no blood or gore, just an accumulation of little things: the Dragon with his back to the camera casually putting on a new set of teeth, telling the reporter they must seal their deal with a kiss, slowly bending his face towards him; cut to the exterior of the house, with birds calling across the night sky, perhaps implying the lipless screaming that is going on within.

It’s worth mentioning that the scene is brightly lit, and it may even be daylight outside the parking lot – the sense of unfathomable evil created here, as elsewhere in Manhunter, has nothing to do with dark shadows or what we think of as the regular trappings of horror cinema. This is a classic example of a film that achieves very menacing effects by keeping explicit detail to a minimum. In Harris’s book, we are told in a single terse sentence that the killer bites off the captive reporter’s lips. The visualisation of this moment in the film is even more restrained – no blood or gore, just an accumulation of little things: the Dragon with his back to the camera casually putting on a new set of teeth, telling the reporter they must seal their deal with a kiss, slowly bending his face towards him; cut to the exterior of the house, with birds calling across the night sky, perhaps implying the lipless screaming that is going on within.In fact, some of the scariest scenes in the film are almost unnaturally bright, and the refusal to overuse genre conventions is reflected in the art design in the Hannibal Lecter scenes, which contrast strongly with the ones in The Silence of the Lambs. The later film showed Lecter incarcerated in a gloomy, dungeon-like prison cell that looked like it might have rats scuffling about and a private uncovered sewer running down the corridor outside, while Manhunter has him in a neat, blindingly white room where you could almost smell the anti-septic (I kept feeling that the doctor had a generous dose of Brylcreem in his hair!).

But the sterile tidiness of the setting only enhances the creepiness of these scenes: Lecter’s most distinct qualities – his old-world courtliness, his ability to look deep into the hearts and minds of others, and to manipulate their emotions – are very much on view. Visiting him in his cell, Will Graham is confronted with the terrifying knowledge that he has a deeply psychological connection with the man sitting before him, and that he might easily become a monster by wrestling with monsters. When Graham dashes out of the building after their meeting – even though the only demon pursuing him is the one inside his own mind – you can almost hear his heart pounding. And your own too. If the TV series comes close to replicating the insidiously scary quality of this film, it should be worth watching.

But the sterile tidiness of the setting only enhances the creepiness of these scenes: Lecter’s most distinct qualities – his old-world courtliness, his ability to look deep into the hearts and minds of others, and to manipulate their emotions – are very much on view. Visiting him in his cell, Will Graham is confronted with the terrifying knowledge that he has a deeply psychological connection with the man sitting before him, and that he might easily become a monster by wrestling with monsters. When Graham dashes out of the building after their meeting – even though the only demon pursuing him is the one inside his own mind – you can almost hear his heart pounding. And your own too. If the TV series comes close to replicating the insidiously scary quality of this film, it should be worth watching.[Did a version of this for my DNA column. More thoughts on horror movies infecting the real world in my essay "Monsters I Have Known". And earlier posts on Thomas Harris and Hannibal Lecter here, here and here.]

Published on May 16, 2013 06:25

May 8, 2013

Fathers and storytellers (notes on Bombay Talkies)

Last month I wrote about a film –

Lessons in Forgetting

– that centres on a protective father and his free-spirited daughter, the latter’s personality colliding with stereotypical ideas about the “good Indian girl”. Coincidentally, a few days ago, while watching the anthology film

Bombay Talkies

, it struck me that all four short movies in it touch on the relationship between fathers and their children, as well as on changing perceptions of masculinity and “male roles”. And a buried theme is a man’s ability – or inability – to tell stories and to deal with different types of narratives.

In fact, the very first scene in Bombay Talkies – in the short film directed by Karan Johar – has a young man angrily confronting his intolerant father who can’t accept, or perhaps even comprehend, that his son is gay. (The film’s title “Ajeeb Dastaan Hai Yeh” comes from one of the great Hindi-film songs, a rendition of which is beautifully used here, but it can also at a stretch be translated as “This is a queer tale”.) Later, in Zoya Akhtar’s short film, another middle-class father – more sensitive on the face of it, but also a man who has clear ideas about what a son should grow up to be – slaps his little boy when he sees him dressed in a girl’s clothes.

There is some ambiguity in this child’s obsession with “Sheila”, the Katrina Kaif character in the Tees Maar Khan item number: does it entail a straight crush on Kaif, expressed through joyful imitation (I’m thinking now of my own childhood dalliances with Parveen Babi or Sridevi songs), or does it reflect gender identification, a biological imperative to “be” a girl? Whatever the case, Akhtar’s film ends with an idyllic scene where the boy gets to perform “Sheila ki Jawani” in front of a small, initially bemused but eventually appreciative audience. Beyond this, his future is uncertain; it’s hard to see him pursuing his dancing ambitions in the long run without a serious conflict with his dad.

There is some ambiguity in this child’s obsession with “Sheila”, the Katrina Kaif character in the Tees Maar Khan item number: does it entail a straight crush on Kaif, expressed through joyful imitation (I’m thinking now of my own childhood dalliances with Parveen Babi or Sridevi songs), or does it reflect gender identification, a biological imperative to “be” a girl? Whatever the case, Akhtar’s film ends with an idyllic scene where the boy gets to perform “Sheila ki Jawani” in front of a small, initially bemused but eventually appreciative audience. Beyond this, his future is uncertain; it’s hard to see him pursuing his dancing ambitions in the long run without a serious conflict with his dad.

Watching that scene, I couldn’t help think that exactly a hundred years ago Dadasaheb Phalke was making films where male actors performed in drag (because respectable women weren’t supposed to act in these shady motion-picture things) - and this led to reflections on gender roles and the creative impulse. In a world that encourages easy classifications, artists, performers or creative people are supposed to be particularly sensitive, and “sensitivity” in turn – broadly defined – is a trait associated more with women than with men. But think of gender characteristics and behaviour as existing along a continuing line (rather than clearly demarcated), and there may be something to the idea that when a man performs on stage, or briefly turns storyteller for his child or for a group of people in his train compartment (which are things that happen in Bombay Talkies), he is tapping into his existing “feminine” side. Or that he is temporarily made more introspective, placed at a remove from the aggression that society often demands of men. (Those men in Phalke’s films – some of them might have felt embarrassed in women’s clothes, but the more dedicated actors among them may have felt briefly liberated from gender expectations. In addition to having a grand time preening about the set, or just reveling in the experience of being “someone else”.)

often demands of men. (Those men in Phalke’s films – some of them might have felt embarrassed in women’s clothes, but the more dedicated actors among them may have felt briefly liberated from gender expectations. In addition to having a grand time preening about the set, or just reveling in the experience of being “someone else”.)

Bombay Talkies has a number of characters who are performers or mimics or tellers of tales, or people who (channeling Eliot) prepare a face each morning before going out to deal with the world. In Johar’s film, Gayatri (Rani Mukherjee) and her husband are living a lie of sorts; one can easily see the little boy in Akhtar’s film growing up to do the same thing; in Dibakar Banerjee’s film, Purandar (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) dreams of getting rich through emu-farming (though the bird is clearly taking more than it gives) while his mundane real-world existence requires that he heads out to find a building-watchman job where (as he himself puts it) you aren’t required to do much more than stand at attention for hours on end.

Purandar has other dimensions: he is a loving father who unselfconsciously does household work alongside his wife and is apparently comfortable in female presence, hanging about with the women of his chawl as they exchange a salty joke or two. Perhaps these traits are inseparable from his qualities as an actor who brings all his integrity to a bit-part role, and as a storyteller who puts on a silent performance for his little girl at the end. (Banerjee – who is of course a storyteller himself – has said that his own experience with fatherhood informed his treatment of this narrative.)

Finally, in Anurag Kashyap’s film about a son who travels to Bombay to try and meet his father’s favourite film star, I think one can suggest that movie-love has turned both the protagonist Vijay and his father into raconteurs – people who have a feel for the spoken word, for parody, dramatic flow and the right pauses. They are amateur performers, and I’d think this would make them more attentive people and strengthen the bond between them. If violence and intolerance are failures of the imagination, perhaps the problem with the fathers in Johar’s and Akhtar’s films is that never having developed a taste for fantasy and role-playing, they lack the empathy that comes with it.

*****

Sidenote: In reviews and in casual discussions with friends, I have heard Kashyap’s film being described as disappointingly simple – and indeed, on the face of it, there is something pedestrian about the story of a young man trying to get a darshan of Amitabh Bachchan (who eventually “blesses” us viewers with a cameo appearance and underlines His divinity by doing unto a murabba what Lord Rama did unto the berry offered him by Shabari). It might seem even more trite if you recall all the behind-the-scenes talk about Kashyap’s real-life reconciliation with Bachchan, and how gratified he seemed by it. But given this director’s sly sense of humour and the awareness in his earlier work of the subtle ways in which worship and irreverence mingle (see his superb short film Pramod Bhai 23, for example), I think the story invites more than a face-value reading.

Vineet Kumar is very good as Vijay, but also consider the casting in light of the small part Kumar played in Kashyap’s

Gangs of Wasseypur

. There he was Sardar Singh’s eldest son Danish, the heir apparent, with the dialogue at one point likening him to the Vijay played by Bachchan in

Trishul

– the clear hero of that film, whose smouldering presence made younger brother Shashi Kapoor seem effete in comparison. (Indeed there is an oft-circulated joke that Shashi Kapoor was one of Bachchan’s most convincing heroines. In Trishul, when the two men have a fight scene where they get to land an equal number of punches on each other – the obligatory ego-salve for male stars of the time – you don’t for a minute buy into it.)

Vineet Kumar is very good as Vijay, but also consider the casting in light of the small part Kumar played in Kashyap’s

Gangs of Wasseypur

. There he was Sardar Singh’s eldest son Danish, the heir apparent, with the dialogue at one point likening him to the Vijay played by Bachchan in

Trishul

– the clear hero of that film, whose smouldering presence made younger brother Shashi Kapoor seem effete in comparison. (Indeed there is an oft-circulated joke that Shashi Kapoor was one of Bachchan’s most convincing heroines. In Trishul, when the two men have a fight scene where they get to land an equal number of punches on each other – the obligatory ego-salve for male stars of the time – you don’t for a minute buy into it.)

But Gangs of Wasseypur’s depiction of life as the banana peel on which the fondest cinematic fantasies may slip included a sequence of events where the limp-wristed younger brother Faisal becomes - to his own surprise - the film's protagonist. “Jab aankh khuli to dekha ki hum Shashi Kapoor hai. Bachchan toh koi aur hai,” Faisal says in an earlier moment of drug-addled self-pity, but this “second lead” ends up as the kingpin after his elder brother is casually bumped off. Watch GoW, then see Vijay’s father in Bombay Talkies mimic Dilip Kumar while telling his story about his own encounter with that thespian decades earlier, and consider the eventual fate of the murabba that Bachchan so self-importantly bites into; I think Kashyap’s film is more than a straight-faced, rose-tinted view of supplicants trying to collect stardust in a glass jar.

In fact, the very first scene in Bombay Talkies – in the short film directed by Karan Johar – has a young man angrily confronting his intolerant father who can’t accept, or perhaps even comprehend, that his son is gay. (The film’s title “Ajeeb Dastaan Hai Yeh” comes from one of the great Hindi-film songs, a rendition of which is beautifully used here, but it can also at a stretch be translated as “This is a queer tale”.) Later, in Zoya Akhtar’s short film, another middle-class father – more sensitive on the face of it, but also a man who has clear ideas about what a son should grow up to be – slaps his little boy when he sees him dressed in a girl’s clothes.

There is some ambiguity in this child’s obsession with “Sheila”, the Katrina Kaif character in the Tees Maar Khan item number: does it entail a straight crush on Kaif, expressed through joyful imitation (I’m thinking now of my own childhood dalliances with Parveen Babi or Sridevi songs), or does it reflect gender identification, a biological imperative to “be” a girl? Whatever the case, Akhtar’s film ends with an idyllic scene where the boy gets to perform “Sheila ki Jawani” in front of a small, initially bemused but eventually appreciative audience. Beyond this, his future is uncertain; it’s hard to see him pursuing his dancing ambitions in the long run without a serious conflict with his dad.

There is some ambiguity in this child’s obsession with “Sheila”, the Katrina Kaif character in the Tees Maar Khan item number: does it entail a straight crush on Kaif, expressed through joyful imitation (I’m thinking now of my own childhood dalliances with Parveen Babi or Sridevi songs), or does it reflect gender identification, a biological imperative to “be” a girl? Whatever the case, Akhtar’s film ends with an idyllic scene where the boy gets to perform “Sheila ki Jawani” in front of a small, initially bemused but eventually appreciative audience. Beyond this, his future is uncertain; it’s hard to see him pursuing his dancing ambitions in the long run without a serious conflict with his dad.Watching that scene, I couldn’t help think that exactly a hundred years ago Dadasaheb Phalke was making films where male actors performed in drag (because respectable women weren’t supposed to act in these shady motion-picture things) - and this led to reflections on gender roles and the creative impulse. In a world that encourages easy classifications, artists, performers or creative people are supposed to be particularly sensitive, and “sensitivity” in turn – broadly defined – is a trait associated more with women than with men. But think of gender characteristics and behaviour as existing along a continuing line (rather than clearly demarcated), and there may be something to the idea that when a man performs on stage, or briefly turns storyteller for his child or for a group of people in his train compartment (which are things that happen in Bombay Talkies), he is tapping into his existing “feminine” side. Or that he is temporarily made more introspective, placed at a remove from the aggression that society

often demands of men. (Those men in Phalke’s films – some of them might have felt embarrassed in women’s clothes, but the more dedicated actors among them may have felt briefly liberated from gender expectations. In addition to having a grand time preening about the set, or just reveling in the experience of being “someone else”.)

often demands of men. (Those men in Phalke’s films – some of them might have felt embarrassed in women’s clothes, but the more dedicated actors among them may have felt briefly liberated from gender expectations. In addition to having a grand time preening about the set, or just reveling in the experience of being “someone else”.)Bombay Talkies has a number of characters who are performers or mimics or tellers of tales, or people who (channeling Eliot) prepare a face each morning before going out to deal with the world. In Johar’s film, Gayatri (Rani Mukherjee) and her husband are living a lie of sorts; one can easily see the little boy in Akhtar’s film growing up to do the same thing; in Dibakar Banerjee’s film, Purandar (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) dreams of getting rich through emu-farming (though the bird is clearly taking more than it gives) while his mundane real-world existence requires that he heads out to find a building-watchman job where (as he himself puts it) you aren’t required to do much more than stand at attention for hours on end.

Purandar has other dimensions: he is a loving father who unselfconsciously does household work alongside his wife and is apparently comfortable in female presence, hanging about with the women of his chawl as they exchange a salty joke or two. Perhaps these traits are inseparable from his qualities as an actor who brings all his integrity to a bit-part role, and as a storyteller who puts on a silent performance for his little girl at the end. (Banerjee – who is of course a storyteller himself – has said that his own experience with fatherhood informed his treatment of this narrative.)

Finally, in Anurag Kashyap’s film about a son who travels to Bombay to try and meet his father’s favourite film star, I think one can suggest that movie-love has turned both the protagonist Vijay and his father into raconteurs – people who have a feel for the spoken word, for parody, dramatic flow and the right pauses. They are amateur performers, and I’d think this would make them more attentive people and strengthen the bond between them. If violence and intolerance are failures of the imagination, perhaps the problem with the fathers in Johar’s and Akhtar’s films is that never having developed a taste for fantasy and role-playing, they lack the empathy that comes with it.

*****

Sidenote: In reviews and in casual discussions with friends, I have heard Kashyap’s film being described as disappointingly simple – and indeed, on the face of it, there is something pedestrian about the story of a young man trying to get a darshan of Amitabh Bachchan (who eventually “blesses” us viewers with a cameo appearance and underlines His divinity by doing unto a murabba what Lord Rama did unto the berry offered him by Shabari). It might seem even more trite if you recall all the behind-the-scenes talk about Kashyap’s real-life reconciliation with Bachchan, and how gratified he seemed by it. But given this director’s sly sense of humour and the awareness in his earlier work of the subtle ways in which worship and irreverence mingle (see his superb short film Pramod Bhai 23, for example), I think the story invites more than a face-value reading.

Vineet Kumar is very good as Vijay, but also consider the casting in light of the small part Kumar played in Kashyap’s

Gangs of Wasseypur

. There he was Sardar Singh’s eldest son Danish, the heir apparent, with the dialogue at one point likening him to the Vijay played by Bachchan in

Trishul

– the clear hero of that film, whose smouldering presence made younger brother Shashi Kapoor seem effete in comparison. (Indeed there is an oft-circulated joke that Shashi Kapoor was one of Bachchan’s most convincing heroines. In Trishul, when the two men have a fight scene where they get to land an equal number of punches on each other – the obligatory ego-salve for male stars of the time – you don’t for a minute buy into it.)

Vineet Kumar is very good as Vijay, but also consider the casting in light of the small part Kumar played in Kashyap’s

Gangs of Wasseypur

. There he was Sardar Singh’s eldest son Danish, the heir apparent, with the dialogue at one point likening him to the Vijay played by Bachchan in

Trishul

– the clear hero of that film, whose smouldering presence made younger brother Shashi Kapoor seem effete in comparison. (Indeed there is an oft-circulated joke that Shashi Kapoor was one of Bachchan’s most convincing heroines. In Trishul, when the two men have a fight scene where they get to land an equal number of punches on each other – the obligatory ego-salve for male stars of the time – you don’t for a minute buy into it.)But Gangs of Wasseypur’s depiction of life as the banana peel on which the fondest cinematic fantasies may slip included a sequence of events where the limp-wristed younger brother Faisal becomes - to his own surprise - the film's protagonist. “Jab aankh khuli to dekha ki hum Shashi Kapoor hai. Bachchan toh koi aur hai,” Faisal says in an earlier moment of drug-addled self-pity, but this “second lead” ends up as the kingpin after his elder brother is casually bumped off. Watch GoW, then see Vijay’s father in Bombay Talkies mimic Dilip Kumar while telling his story about his own encounter with that thespian decades earlier, and consider the eventual fate of the murabba that Bachchan so self-importantly bites into; I think Kashyap’s film is more than a straight-faced, rose-tinted view of supplicants trying to collect stardust in a glass jar.

Published on May 08, 2013 05:44

May 7, 2013

Legends of Halahala - silent pictures from another world

[Did this piece for the magazine Democratic World]

What people are willing to consider literary, or even literate, is highly variable. Often, one hears the casual remark “This mass-market/popular novel is not literature” – a statement that, apart from being inaccurate at a purely definition-based level, also suggests an elitism that runs against the long, complex history of art and popular culture. However, even the most broad-based definitions of literature are sure to contain the word “writing”. It is taken for granted that words, made up of those tiny shapes we call alphabets – so intimidating when we can’t decipher them, and so empowering when we can – are involved. And this may be why, when asked about my favourite Indian novels of the past year, I hesitate for a second before mentioning Legends of Halahala .

But only for a second. This is a work of graphic fiction by the hugely talented artist Appupen (the pen name of George Mathen), his second after the extraordinary

Moonward

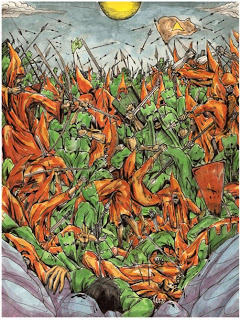

. Like that book, Legends of Halahala is set on a planet that resembles our own in many basic ways. It employs different drawing styles to tell five stories set in separate periods, each presenting a perspective on love, obsession and its effects. There is conventional, youthful (some might say foolish and impetuous) romance, but there is also the cutesy idea of two oddball, parasite-like creatures – from the remote “Oberian” era – being each other’s forever-companions. There is a man pining for the super-heroine he encountered as a child, and another man – a swarthy, motorbike-riding daredevil – who is the rescuer of, and then the abductor of, a supermodel’s absconding left breast (!). And in the bleakest of these tales, titled “16917P’s Masterpiece”, there is the love of artistic creation as a form of self-affirmation.

But only for a second. This is a work of graphic fiction by the hugely talented artist Appupen (the pen name of George Mathen), his second after the extraordinary

Moonward

. Like that book, Legends of Halahala is set on a planet that resembles our own in many basic ways. It employs different drawing styles to tell five stories set in separate periods, each presenting a perspective on love, obsession and its effects. There is conventional, youthful (some might say foolish and impetuous) romance, but there is also the cutesy idea of two oddball, parasite-like creatures – from the remote “Oberian” era – being each other’s forever-companions. There is a man pining for the super-heroine he encountered as a child, and another man – a swarthy, motorbike-riding daredevil – who is the rescuer of, and then the abductor of, a supermodel’s absconding left breast (!). And in the bleakest of these tales, titled “16917P’s Masterpiece”, there is the love of artistic creation as a form of self-affirmation.

Most intriguingly, the book is almost completely wordless. This is not a minor achievement. Last year, the Chennai-based publishing house Blaft produced an anthology of visual storytelling titled The Obliterary Journal . The name came from the book’s tongue-in-cheek mission to “obliterate” conventional literature – and yet, most of the stories in that collection, though beautifully drawn, did use text; words and images worked in unison. And this has been true of the majority of international graphic novels too, even the ones that do spectacular things with pictorial form. Alan Moore’s Watchmen – about an alternative America where costumed “superheroes” are becoming irrelevant in the face of the world’s biggest problems – is one of the most intricate works of storytelling I have ever seen, in its use of visuals that echo each other, and an intense narrative within a narrative. But it is also a book that you read – the first time, at least – in the normal way, since the story is propelled by dialogues and by stream-of-consciousness musings from a journal maintained by one of the main characters.

Reading a narrative made up entirely of drawings involves a different cerebral process, but within a few pages of Legends of Halahala I was hooked; so adept and fluid is Appupen’s artwork that these stories don’t need words. The few bursts of conversation there are take the form of exclamations and are depicted in a droll, almost cheesily visual way: when a king’s servant has to announce that the royal dinner is ready, the speech bubble issuing from his mouth contains a picture of a plate and cutlery; when the king and queen realise their daughter is missing and shout out her name, we only see her image in the speech balloon (we never learn what she is called); and after a dragon-like creature is sternly instructed to stop setting things ablaze with his fire-breath, we see a “no smoking” sign emanating from his head as he crawls sheepishly away. In a cheeky touch, most of the written words that adorn the book’s back-cover are fake blurbs such as “Book of the year!” by a publication called The Halahala Observer.

Reading a narrative made up entirely of drawings involves a different cerebral process, but within a few pages of Legends of Halahala I was hooked; so adept and fluid is Appupen’s artwork that these stories don’t need words. The few bursts of conversation there are take the form of exclamations and are depicted in a droll, almost cheesily visual way: when a king’s servant has to announce that the royal dinner is ready, the speech bubble issuing from his mouth contains a picture of a plate and cutlery; when the king and queen realise their daughter is missing and shout out her name, we only see her image in the speech balloon (we never learn what she is called); and after a dragon-like creature is sternly instructed to stop setting things ablaze with his fire-breath, we see a “no smoking” sign emanating from his head as he crawls sheepishly away. In a cheeky touch, most of the written words that adorn the book’s back-cover are fake blurbs such as “Book of the year!” by a publication called The Halahala Observer.

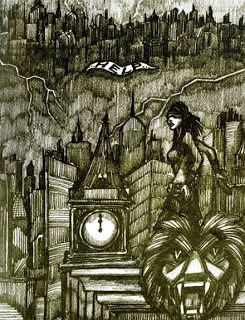

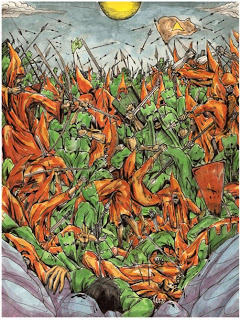

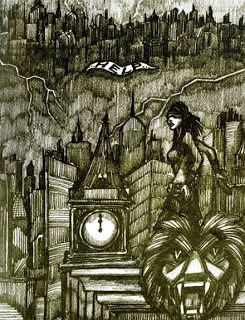

But it is the true silences that are most impressive. The first story – about star-crossed lovers whose fathers rule rival kingdoms – is the most straightforward one, linear and very easy on the eye. It is also bright and vividly coloured, which is central to its purpose: the kingdoms are represented by green and orange respectively, and this distinguishing colour scheme runs through the story, right up to a cheeky last panel where the two lovers are finally united and the picture of a heart on a flag brings the two colours together. Contrast this look with that of the next story, drawn in deliberately gloomy black and white, where a child and his parents – walking the streets of what looks like a Hollywood noir film from the 1940s – are rescued from a monster by Ghost Girl. (When we seen the grown up version of the boy years later – a depressed-looking man still haunted by the memory of his saviour – the panels acquire a neon yellow tinge.)

Just as interesting as the differences, though, are the similarities – the visual motifs that subtly connect the tales. For instance, the opening illustrations for three of the stories involve a chasm that has to be bridged: in “Stupid’s Arrow”, it is the valley that divides the kingdoms, a tenuous rope bridge stretched across it; in “The Saga of Ghost Girl”, the skyscrapers of a metropolis are drawn in a slanted way so that the gap between them becomes another sort of valley, and we see the small figure of the super-heroine swinging from one building to another. And there are many other touches that you might properly register only on a second or third read. (Isn’t the image on the opening page of the first story – the silhouette of the valley and the rocky hills – akin to the bottom half of an India map, complete with a little Sri Lanka tapering away at the bottom? And if so, could the kingdoms stand for the politics associated with the western and eastern extremes of the country? Or is this over-analysis? Decide for yourself.)

Three of the stories in Legends of Halahala end with clear heart symbols, but if you squint at the final pages of the other two you might see distorted heart shapes in them too: in the rings of cigarette smoke floating across a city’s dark skyline. Or in the broken pieces of a plaque on which a man banished from a machine-run land has inscribed “16917P was here” as he uses his art to battle oblivion - by building a monument to assert his presence in a world where he is an outcast. On the evidence of his two books so far, Appupen’s own tryst with literary fame is well underway, and happily graphic novels are not as marginalised as they once were.

Three of the stories in Legends of Halahala end with clear heart symbols, but if you squint at the final pages of the other two you might see distorted heart shapes in them too: in the rings of cigarette smoke floating across a city’s dark skyline. Or in the broken pieces of a plaque on which a man banished from a machine-run land has inscribed “16917P was here” as he uses his art to battle oblivion - by building a monument to assert his presence in a world where he is an outcast. On the evidence of his two books so far, Appupen’s own tryst with literary fame is well underway, and happily graphic novels are not as marginalised as they once were.

[A few earlier posts on graphic novels and visual storytelling: the many faces of the Indian comics industry; Jis desh mein manga bikhti hai; the Pao Collective's anthology; Ambedkar in Gond art; the maali who weeded out myth; Kashmir Pending and The Barn Owl; on reviewing a graphic novel]

What people are willing to consider literary, or even literate, is highly variable. Often, one hears the casual remark “This mass-market/popular novel is not literature” – a statement that, apart from being inaccurate at a purely definition-based level, also suggests an elitism that runs against the long, complex history of art and popular culture. However, even the most broad-based definitions of literature are sure to contain the word “writing”. It is taken for granted that words, made up of those tiny shapes we call alphabets – so intimidating when we can’t decipher them, and so empowering when we can – are involved. And this may be why, when asked about my favourite Indian novels of the past year, I hesitate for a second before mentioning Legends of Halahala .

But only for a second. This is a work of graphic fiction by the hugely talented artist Appupen (the pen name of George Mathen), his second after the extraordinary

Moonward

. Like that book, Legends of Halahala is set on a planet that resembles our own in many basic ways. It employs different drawing styles to tell five stories set in separate periods, each presenting a perspective on love, obsession and its effects. There is conventional, youthful (some might say foolish and impetuous) romance, but there is also the cutesy idea of two oddball, parasite-like creatures – from the remote “Oberian” era – being each other’s forever-companions. There is a man pining for the super-heroine he encountered as a child, and another man – a swarthy, motorbike-riding daredevil – who is the rescuer of, and then the abductor of, a supermodel’s absconding left breast (!). And in the bleakest of these tales, titled “16917P’s Masterpiece”, there is the love of artistic creation as a form of self-affirmation.

But only for a second. This is a work of graphic fiction by the hugely talented artist Appupen (the pen name of George Mathen), his second after the extraordinary

Moonward

. Like that book, Legends of Halahala is set on a planet that resembles our own in many basic ways. It employs different drawing styles to tell five stories set in separate periods, each presenting a perspective on love, obsession and its effects. There is conventional, youthful (some might say foolish and impetuous) romance, but there is also the cutesy idea of two oddball, parasite-like creatures – from the remote “Oberian” era – being each other’s forever-companions. There is a man pining for the super-heroine he encountered as a child, and another man – a swarthy, motorbike-riding daredevil – who is the rescuer of, and then the abductor of, a supermodel’s absconding left breast (!). And in the bleakest of these tales, titled “16917P’s Masterpiece”, there is the love of artistic creation as a form of self-affirmation.Most intriguingly, the book is almost completely wordless. This is not a minor achievement. Last year, the Chennai-based publishing house Blaft produced an anthology of visual storytelling titled The Obliterary Journal . The name came from the book’s tongue-in-cheek mission to “obliterate” conventional literature – and yet, most of the stories in that collection, though beautifully drawn, did use text; words and images worked in unison. And this has been true of the majority of international graphic novels too, even the ones that do spectacular things with pictorial form. Alan Moore’s Watchmen – about an alternative America where costumed “superheroes” are becoming irrelevant in the face of the world’s biggest problems – is one of the most intricate works of storytelling I have ever seen, in its use of visuals that echo each other, and an intense narrative within a narrative. But it is also a book that you read – the first time, at least – in the normal way, since the story is propelled by dialogues and by stream-of-consciousness musings from a journal maintained by one of the main characters.

Reading a narrative made up entirely of drawings involves a different cerebral process, but within a few pages of Legends of Halahala I was hooked; so adept and fluid is Appupen’s artwork that these stories don’t need words. The few bursts of conversation there are take the form of exclamations and are depicted in a droll, almost cheesily visual way: when a king’s servant has to announce that the royal dinner is ready, the speech bubble issuing from his mouth contains a picture of a plate and cutlery; when the king and queen realise their daughter is missing and shout out her name, we only see her image in the speech balloon (we never learn what she is called); and after a dragon-like creature is sternly instructed to stop setting things ablaze with his fire-breath, we see a “no smoking” sign emanating from his head as he crawls sheepishly away. In a cheeky touch, most of the written words that adorn the book’s back-cover are fake blurbs such as “Book of the year!” by a publication called The Halahala Observer.

Reading a narrative made up entirely of drawings involves a different cerebral process, but within a few pages of Legends of Halahala I was hooked; so adept and fluid is Appupen’s artwork that these stories don’t need words. The few bursts of conversation there are take the form of exclamations and are depicted in a droll, almost cheesily visual way: when a king’s servant has to announce that the royal dinner is ready, the speech bubble issuing from his mouth contains a picture of a plate and cutlery; when the king and queen realise their daughter is missing and shout out her name, we only see her image in the speech balloon (we never learn what she is called); and after a dragon-like creature is sternly instructed to stop setting things ablaze with his fire-breath, we see a “no smoking” sign emanating from his head as he crawls sheepishly away. In a cheeky touch, most of the written words that adorn the book’s back-cover are fake blurbs such as “Book of the year!” by a publication called The Halahala Observer.But it is the true silences that are most impressive. The first story – about star-crossed lovers whose fathers rule rival kingdoms – is the most straightforward one, linear and very easy on the eye. It is also bright and vividly coloured, which is central to its purpose: the kingdoms are represented by green and orange respectively, and this distinguishing colour scheme runs through the story, right up to a cheeky last panel where the two lovers are finally united and the picture of a heart on a flag brings the two colours together. Contrast this look with that of the next story, drawn in deliberately gloomy black and white, where a child and his parents – walking the streets of what looks like a Hollywood noir film from the 1940s – are rescued from a monster by Ghost Girl. (When we seen the grown up version of the boy years later – a depressed-looking man still haunted by the memory of his saviour – the panels acquire a neon yellow tinge.)

Just as interesting as the differences, though, are the similarities – the visual motifs that subtly connect the tales. For instance, the opening illustrations for three of the stories involve a chasm that has to be bridged: in “Stupid’s Arrow”, it is the valley that divides the kingdoms, a tenuous rope bridge stretched across it; in “The Saga of Ghost Girl”, the skyscrapers of a metropolis are drawn in a slanted way so that the gap between them becomes another sort of valley, and we see the small figure of the super-heroine swinging from one building to another. And there are many other touches that you might properly register only on a second or third read. (Isn’t the image on the opening page of the first story – the silhouette of the valley and the rocky hills – akin to the bottom half of an India map, complete with a little Sri Lanka tapering away at the bottom? And if so, could the kingdoms stand for the politics associated with the western and eastern extremes of the country? Or is this over-analysis? Decide for yourself.)

Three of the stories in Legends of Halahala end with clear heart symbols, but if you squint at the final pages of the other two you might see distorted heart shapes in them too: in the rings of cigarette smoke floating across a city’s dark skyline. Or in the broken pieces of a plaque on which a man banished from a machine-run land has inscribed “16917P was here” as he uses his art to battle oblivion - by building a monument to assert his presence in a world where he is an outcast. On the evidence of his two books so far, Appupen’s own tryst with literary fame is well underway, and happily graphic novels are not as marginalised as they once were.

Three of the stories in Legends of Halahala end with clear heart symbols, but if you squint at the final pages of the other two you might see distorted heart shapes in them too: in the rings of cigarette smoke floating across a city’s dark skyline. Or in the broken pieces of a plaque on which a man banished from a machine-run land has inscribed “16917P was here” as he uses his art to battle oblivion - by building a monument to assert his presence in a world where he is an outcast. On the evidence of his two books so far, Appupen’s own tryst with literary fame is well underway, and happily graphic novels are not as marginalised as they once were.[A few earlier posts on graphic novels and visual storytelling: the many faces of the Indian comics industry; Jis desh mein manga bikhti hai; the Pao Collective's anthology; Ambedkar in Gond art; the maali who weeded out myth; Kashmir Pending and The Barn Owl; on reviewing a graphic novel]

Published on May 07, 2013 04:46

May 4, 2013

Author, auteur, rationalist, fabulist: an essay on Satyajit Ray

[Did this profile of Satyajit Ray for the African magazine Cityscapes. Since the piece was meant for a largely non-Indian readership – including people who would know of Ray only in passing – there is necessarily some formality and simplification, including the setting down of biographical detail that is widely known in India. But I tried to avoid making it a dry, encyclopaedia-like piece and to discuss something I personally find intriguing, the divide between Ray’s “serious” work and his excursions into fantasy. As always, no attempt at being “comprehensive” here: it would be possible to write a hundred such essays about Ray without saying everything interesting there is to say about him.]

------------------

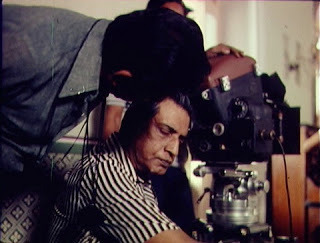

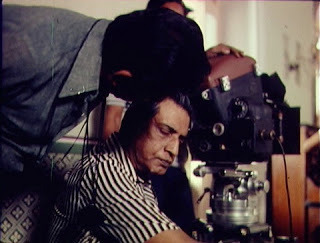

The tall man – very tall by Indian standards – is moving about a cluttered room, monitoring elements of set design while his film crew get their equipment in place. Depending on whom he talks to, he alternates between English and his mother tongue Bengali, speaking both languages with casual fluency. He asks an actor to try a rehearsal without his false moustache, jokes and banters for a few seconds, but then shifts quickly back into the meter of the sombre professional, the father figure keeping a close watch on things. He sits on the floor at an uncomfortable, slanted angle and looks through the viewfinder of the bulky camera, placing a cloth over his head to shut out peripheral light; so pronounced is the difference in height between him and his assistants, it's akin to seeing Santa surrounded by his elves, examining the underside of his sleigh.

Satyajit Ray is multi-tasking in ways you would expect most directors to do during a shoot, but there is something poetically apt about this busy yet homely scene, which opens a 1985 documentary - made by Shyam Benegal - about his life and career. Ray was an auteur in the most precise sense of that versatile word. Apart from directing, he wrote most of the screenplays of his movies – some adapted from existing literary works, others from his own stories. He also composed music, drew detailed, artistic storyboards for sequences, designed costumes and promotional posters, and frequently wielded the camera. Above all, he brought his gently intelligent sensibility and a deep-rooted interest in people to nearly everything he did. He was, to take recourse to a cliché with much truth in it, a culmination of what has become known as the Bengali intellectual Renaissance.

Satyajit Ray is multi-tasking in ways you would expect most directors to do during a shoot, but there is something poetically apt about this busy yet homely scene, which opens a 1985 documentary - made by Shyam Benegal - about his life and career. Ray was an auteur in the most precise sense of that versatile word. Apart from directing, he wrote most of the screenplays of his movies – some adapted from existing literary works, others from his own stories. He also composed music, drew detailed, artistic storyboards for sequences, designed costumes and promotional posters, and frequently wielded the camera. Above all, he brought his gently intelligent sensibility and a deep-rooted interest in people to nearly everything he did. He was, to take recourse to a cliché with much truth in it, a culmination of what has become known as the Bengali intellectual Renaissance.

The Indian state of West Bengal, from which Ray hailed, has long been associated with capacious scholarship and a well-rounded cultural education, with the towering figure in its modern history – certainly the one most well-known outside India – being the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, a multitalented writer, artist and song composer. As a young man in the early 1940s, Ray studied art at Shantiniketan, the pastoral university established by Tagore, but this was just one episode in his cultural flowering. He was born – in 1921 – into a family well-steeped in the intellectual life: his grandfather Upendrakishore (a contemporary and friend of Tagore) was a leading writer, printer, composer and a pioneer of modern block-making; Ray’s father Sukumar Ray was a renowned illustrator and practitioner of nonsense verse whose work has delighted generations of young Bengalis (and now, increasingly through translation, young Indians across the country).

From this fecund soil emerged a sensibility so broad that it defies categorisation. If cinema had not struck the young Satyajit’s fancy (he was an enthusiast of Hollywood movies, interested initially in the stars and later in the directors) he might have made an honourable career in many other disciplines. He worked as a visualiser in an advertising agency and as a cover designer for books before embarking on his film career; even today, people who are familiar only with one aspect of his creative life are surprised to discover his many other talents. And for this reason, a useful way of looking at Ray is through the prism of the narrow perceptions that have sometimes been used to define or pigeonhole him. These usually come from those who are only familiar with his work in fragments: viewers from outside India, as well as non-Bengali Indians who may have seen only a few of his films.

Simplistic labels have been imposed on him ever since his debut feature Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) came to international attention and won a prize at the 1956 Cannes festival. Based on a celebrated 19th century novel by BibhutibhushanBandopadhyaya, this subtle, deeply moving film is about a family of impoverished villagers, including a little boy named Apu, who would become the protagonist of the celebrated Apu Trilogy – travelling to Calcutta as an adolescent in Ray’s next film Aparajito (The Unvanquished) and finally coming of age in Apur Sansar (The World of Apu). Though Pather Panchali is rightly regarded a milestone in the history of Indian cinema, it was also the subject of misunderstandings among those who were not yet accustomed to dealing with directors and movies from this country. In a perceptive 1962 essay about a later Ray film

Devi

(The Goddess), the American critic Pauline Kael noted that some early Western reviewers had mistakenly believed Ray was a “primitive” artist and that Apu’s progress over the three films in some way represented the director’s own journey from rural to city life. Indeed, the critic Dwight Macdonald wrote of Apur Sansar that while Ray handled village life well enough, he was “not up to” telling the story of a young writer in a city, which is “a more complex theme” – the implication being that rural stories were somehow truer both to Ray’s own life experience and to the Indian condition in general.

Simplistic labels have been imposed on him ever since his debut feature Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) came to international attention and won a prize at the 1956 Cannes festival. Based on a celebrated 19th century novel by BibhutibhushanBandopadhyaya, this subtle, deeply moving film is about a family of impoverished villagers, including a little boy named Apu, who would become the protagonist of the celebrated Apu Trilogy – travelling to Calcutta as an adolescent in Ray’s next film Aparajito (The Unvanquished) and finally coming of age in Apur Sansar (The World of Apu). Though Pather Panchali is rightly regarded a milestone in the history of Indian cinema, it was also the subject of misunderstandings among those who were not yet accustomed to dealing with directors and movies from this country. In a perceptive 1962 essay about a later Ray film

Devi

(The Goddess), the American critic Pauline Kael noted that some early Western reviewers had mistakenly believed Ray was a “primitive” artist and that Apu’s progress over the three films in some way represented the director’s own journey from rural to city life. Indeed, the critic Dwight Macdonald wrote of Apur Sansar that while Ray handled village life well enough, he was “not up to” telling the story of a young writer in a city, which is “a more complex theme” – the implication being that rural stories were somehow truer both to Ray’s own life experience and to the Indian condition in general.

If so, this is a laughable idea. Ray was very much the product of a cosmopolitan setting and way of life: he lived in a big city, travelled abroad extensively before becoming a filmmaker, and spoke English with a clipped accent that contained traces of the British colonial influence. In choosing to film Bandopadhyaya’s novel with its village setting, he had stepped out of his personal comfort zone: the worlds he chronicled in later, urban films, such as Mahanagar (The Big City) and the Calcutta Trilogy of the 1970s were much more intimately familiar to him than the world of Apu’s penurious family was. These “city films” are diverse in their themes and subject matter, but the best of them are particularly insightful depictions of restive middle-class youngsters in a soft-socialist society increasingly besotted by the go-getting, capitalist way of life – a milieu that was conservative in some ways but forward-looking in other ways – and of how an individual might gradually get corrupted by a system.

If so, this is a laughable idea. Ray was very much the product of a cosmopolitan setting and way of life: he lived in a big city, travelled abroad extensively before becoming a filmmaker, and spoke English with a clipped accent that contained traces of the British colonial influence. In choosing to film Bandopadhyaya’s novel with its village setting, he had stepped out of his personal comfort zone: the worlds he chronicled in later, urban films, such as Mahanagar (The Big City) and the Calcutta Trilogy of the 1970s were much more intimately familiar to him than the world of Apu’s penurious family was. These “city films” are diverse in their themes and subject matter, but the best of them are particularly insightful depictions of restive middle-class youngsters in a soft-socialist society increasingly besotted by the go-getting, capitalist way of life – a milieu that was conservative in some ways but forward-looking in other ways – and of how an individual might gradually get corrupted by a system.

However, there is a related point to be made here. If one is seeking a “quintessential Indian filmmaker” – meaning a director whose work represents the movie-going experience for a majority of Indians – Satyajit Ray was not that man. His films had a cool, formal polish, an organic consistency, which was far removed from the episodic structures and dramatic flourishes of commercial Indian cinema. He was influenced not by local moviemakers but by foreign directors ranging from Jean Renoir to Billy Wilder. And he had a sensibility rooted in classical Western and Bengali literature, which sometimes manifested itself in hidebound snobbery towards films that indulged “style” at the expense of “substance”, or theatrical melodrama over “realism”. In 1947, Ray and some of his friends co-founded Calcutta's first film society. “We were critical of most Indian cinema of the time,” he says in the documentary mentioned at the beginning of this piece, “We found most of our stuff shoddy, theatrical, commercial in a bad way.”

This may also be the time for a personal aside: the cinema of Ray was not the cinema of my childhood. Growing up in north India, I mainly watched the escapist entertainers of the Bombay film industry, latterly known as “Bollywood” – movies that mixed disparate tones and genres and contained narrative-disrupting song-and-dance sequences. It was only in my teens, in the early 1990s – around the time a feeble Ray, lying on his deathbed, was giving his halting acceptance speech for a Lifetime Achievement Oscar – that I entered his world. I had become interested in what we called “world cinema” – beginning with classic Hollywood, then the French, Italian and Japanese movie movements – and I saw Ray’s films as part of a tradition defined by exclusion: everything that was not mainstream Hindi cinema. I grew to love his work, but even today I feel a little lost when faced with specific Bengali references in his films; a little cut off by virtue of not understanding the language or having been born in that cultural tradition. (It doesn’t help that the subtitles on most Indian DVDs are execrable.) I also feel ambivalent about his condescension towards commercial Hindi cinema.

But given the cultural disconnect between my world and his, it is remarkable how accessible Ray’s films were in most ways that mattered. This may be because, as the critic-academic Robin Wood put it, “Ray's films usually deal with human fundamentals that undercut all cultural distinctions.” His best work hinges on instantly recognisable aspects of the human condition: from the loneliness of a bored housewife, dangerously drawn to her younger brother-in-law, in Charulata (one of Ray’s most accomplished films, based on a famous Tagore story) to four restless men making a languid, not properly thought out attempt to escape city life in Aranyer Dinratri (Days and Nights in the Forest). In his capacity to engage with the inner lives of many different types of people and to find the right expression for them, he is one of the most universally appealing of directors.

****

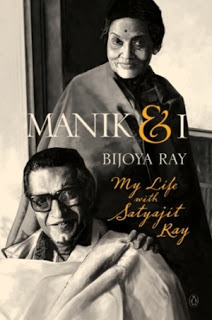

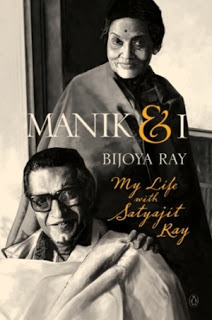

In the memoirs of Ray’s wife Bijoya – recently published in English translation as Manik & I – there is a glimpse of the director as a privileged and mollycoddled man. One anecdote has Ray being startled that Bijoya knew how to replace a fused light-bulb herself, without having to call an electrician. In the no-nonsense style of the spouse who can deconstruct the myth around a great man, she writes: “He never once touched the air conditioner in our room. If he entered the room for a rest and couldn’t see me anywhere, he’d shout out, ‘Where are you? Please switch the AC on for me.’ Such was my husband.”

In the memoirs of Ray’s wife Bijoya – recently published in English translation as Manik & I – there is a glimpse of the director as a privileged and mollycoddled man. One anecdote has Ray being startled that Bijoya knew how to replace a fused light-bulb herself, without having to call an electrician. In the no-nonsense style of the spouse who can deconstruct the myth around a great man, she writes: “He never once touched the air conditioner in our room. If he entered the room for a rest and couldn’t see me anywhere, he’d shout out, ‘Where are you? Please switch the AC on for me.’ Such was my husband.”

Amusing and revealing though these stories are, they should also guard us against making facile connections between an artist’s work and his life; they take nothing away from Ray’s interest in people who were much less privileged, who did not share his background or personal concerns. In fact, “humanist” is a word that has often been used to describe Ray’s film work – so often that it has become a closed term, sufficient in itself. Roughly speaking, it can be taken to mean that he cared deeply about people and their circumstances, and that he chose empathy over judgement (his best films lack villain figures who can serve as easy explanations for why bad things happen). But I would argue that to properly understand this quality, one must recognise how complex and apparently contradictory he could be as an artist.

Consider, for instance, that the man who could be narrow-minded about genre films (in a book review, he airily dismissed Francois Truffaut’s efforts to present Alfred Hitchcock as a serious artist) was the same man who admitted in an essay that if he could take only one film to a desert island, it would be a Marx Brothers movie. The filmmaker known for his literariness and economy of expression also displayed a light, absurdist sense of humour and wrote many delightful stories in such commercially popular genres as science-fiction, detective fiction and horror.

Many of the perceptions of Ray swim around a basic idea: Satyajit Ray was a “serious” filmmaker. Now this statement is not in doubt if the word is used in its broad sense, to describe any rigorous artist who has achieved at a high level. But in a developing country like India, where cinema is often seen as having an overt social responsibility, very sharp lines tend to get drawn between “escapist” and “meaningful” films, and the word “serious” is sometimes used as an approving synonym for pedantry, humourlessness, absence of personal style or lack of interest in things that are not self-evidently a part of the “real” world. However, none of these qualities apply to Ray. There was nothing pedantic about his major work. His narratives are so fluid, it is possible to get so absorbed in his people’s lives, that one is scarcely conscious of watching an “art” film. And the identifiably weaker moments in his oeuvre are the laboured or self-conscious ones. For most of its running time, his 1971 film Seemabaddha (Company Limited) is an absorbing narrative about an upwardly mobile executive slowly being drawn into compromise and amorality. But the very last shot – where a key character literally vanishes into thin air, thereby identifying her as a symbol for the protagonist’s conscience – is one of the notable missteps in Ray’s career, a classic example of a filmmaker spoon-feeding an idea to his audience at the last moment, rather than letting the accumulation of events in the film speak for themselves (as they have been doing).

Many of the perceptions of Ray swim around a basic idea: Satyajit Ray was a “serious” filmmaker. Now this statement is not in doubt if the word is used in its broad sense, to describe any rigorous artist who has achieved at a high level. But in a developing country like India, where cinema is often seen as having an overt social responsibility, very sharp lines tend to get drawn between “escapist” and “meaningful” films, and the word “serious” is sometimes used as an approving synonym for pedantry, humourlessness, absence of personal style or lack of interest in things that are not self-evidently a part of the “real” world. However, none of these qualities apply to Ray. There was nothing pedantic about his major work. His narratives are so fluid, it is possible to get so absorbed in his people’s lives, that one is scarcely conscious of watching an “art” film. And the identifiably weaker moments in his oeuvre are the laboured or self-conscious ones. For most of its running time, his 1971 film Seemabaddha (Company Limited) is an absorbing narrative about an upwardly mobile executive slowly being drawn into compromise and amorality. But the very last shot – where a key character literally vanishes into thin air, thereby identifying her as a symbol for the protagonist’s conscience – is one of the notable missteps in Ray’s career, a classic example of a filmmaker spoon-feeding an idea to his audience at the last moment, rather than letting the accumulation of events in the film speak for themselves (as they have been doing).

An offshoot of the “serious” tag is the idea that Ray was concerned only with content, not with form. But watch the films themselves and this notion quickly dissolves. Even Pather Panchali, his sparsest film on the surface – made when he was a young director with an inexperienced crew, learning on the job – is anything but a bland documentary account of life in an Indian village. It is full of beautifully realised, carefully composed sequences (many of which derive directly from Ray’s delicate storyboard drawings) and thoughtful use of sound and music.

There is clearer evidence of Ray the stylist in such films as his 1958 classic Jalsaghar (The Music Room), about a once-rich landlord now become a relic of a forgotten world. It is obvious right from the opening shot that Ray intended this to be a film of visual flourishes. (In an essay in his book Our Films, Their Films, he admitted that having won an award at Cannes shortly before making Jalsaghar, he had become a little self-conscious and allowed himself the indulgence of a crane for overhead shots.) There are carefully composed shots which draw attention to themselves – a chandelier reflected in a drinking glass, an unsettling zoom in to a spider scuttling across a portrait, a view of a stormy sky seen through the windows of the music room – as well as sequences that stress the contrast between the zamindar’s past glory and the delusions that now crowd his mind. One constantly gets the impression of a director trying to use the camera in inventive ways, as one does in other movies such as the 1966 Nayak (The Actor), with its stylistic nods to scenes from Federico Fellini’s Eight and a Half, Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and other international films, and the 1970 Pratidwandi (The Adversary), which makes effective, ghostly use of negative film at key moments.

There is clearer evidence of Ray the stylist in such films as his 1958 classic Jalsaghar (The Music Room), about a once-rich landlord now become a relic of a forgotten world. It is obvious right from the opening shot that Ray intended this to be a film of visual flourishes. (In an essay in his book Our Films, Their Films, he admitted that having won an award at Cannes shortly before making Jalsaghar, he had become a little self-conscious and allowed himself the indulgence of a crane for overhead shots.) There are carefully composed shots which draw attention to themselves – a chandelier reflected in a drinking glass, an unsettling zoom in to a spider scuttling across a portrait, a view of a stormy sky seen through the windows of the music room – as well as sequences that stress the contrast between the zamindar’s past glory and the delusions that now crowd his mind. One constantly gets the impression of a director trying to use the camera in inventive ways, as one does in other movies such as the 1966 Nayak (The Actor), with its stylistic nods to scenes from Federico Fellini’s Eight and a Half, Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and other international films, and the 1970 Pratidwandi (The Adversary), which makes effective, ghostly use of negative film at key moments.

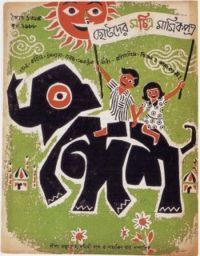

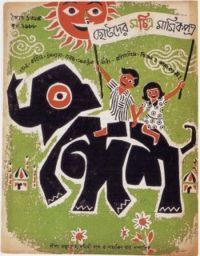

But for the most pronounced sense of Ray’s creative flair and versatility, one should consider a film that has long been among his most beloved and well-known works in Bengal, and at the same time among his most neglected, least-seen films outside India: the 1968 adventure classic Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha). Based on a story by Ray’s grandfather Upendrakishore about two lovable adventurer-musicians who foil a wicked magician’s plans in the fictitious land of Shundi, this film (along with its 1980 sequel Hirak Rajar Deshe) is an important pointer to Ray’s strong fabulist streak, and a conundrum for those who would construct pat narratives about him being the solemn antidote to Bollywood escapism – as a man who only told stark, grounded stories about the “real India”.

But for the most pronounced sense of Ray’s creative flair and versatility, one should consider a film that has long been among his most beloved and well-known works in Bengal, and at the same time among his most neglected, least-seen films outside India: the 1968 adventure classic Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha). Based on a story by Ray’s grandfather Upendrakishore about two lovable adventurer-musicians who foil a wicked magician’s plans in the fictitious land of Shundi, this film (along with its 1980 sequel Hirak Rajar Deshe) is an important pointer to Ray’s strong fabulist streak, and a conundrum for those who would construct pat narratives about him being the solemn antidote to Bollywood escapism – as a man who only told stark, grounded stories about the “real India”.