Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 72

November 28, 2013

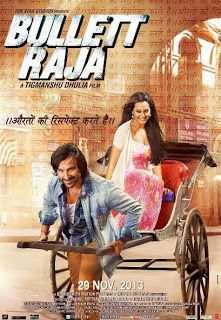

The goonda as political commando - on Tigmanshu Dhulia's Bullett Raja

[Did a shorter version of this review for Business Standard]

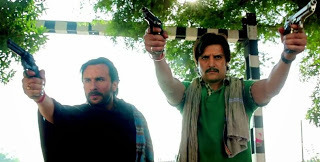

“Halka paani ya bhadkeela?” is the question with which the friendship between Raja Mishra (Saif Ali Khan) and Rudra (Jimmy Shergill) begins. The setting is a wedding party and Rudra is asking Raja if he is fine with the soft drink he has just been offered or if he wants something flashier, more potent. Raja opts for the latter, and he certainly gets it over the course of this noisy film. After a few hours of bonding over liquor, banter and an item girl, the two men expertly fight off an attack on the wedding house, and so their fate is sealed: they are subsequently drawn into the politics and mafia wars of the UP heartland. It is as if the simple act of drinking “bhadkeela paani” has engendered events that turn a regular, job-seeking boy into a superhero, a goonda or a “political commando” (depending on your perspective). Even as Raja and Rudra retain their goofiness and basic likability, the stakes will keep rising for them.

The opening credits of Tigmanshu Dhulia’s

Bullett Raja

are all about colour and flash and dhishum and dhishkiyaon, and that’s mostly what the film turns out to be too. Much has already been said about Dhulia, a director of grounded hinterland stories with well-written characters, making a no-holds-barred commercial film, a “potboiler”. Normally I’m wary of such classifications, but after watching Bullett Raja I had to concede the point. This is a clear homage to the mainstream Hindi film of the 1970s and 80s. There is a Sholay reference early on (“Hamesha do kyon hote hain?” – “Why are there always two?” – grumbles a head villain whose men have been vanquished by Raja and Rudra), and the very presence of Gulshan Grover, Chunky Pandey and Raj Babbar (all of whom are reasonably well used, with Pandey hamming it up from behind red-tinted glasses) is a reminder of less sophisticated masala movies from times past. Bullett Raja reaches for the tone of those films without trying to be a cheeky, post-modern commentary on them; there is even a scene – filmed straight, without irony – involving the death of a loved one and the hero swearing vengeance through the flames of a funeral pyre.

The opening credits of Tigmanshu Dhulia’s

Bullett Raja

are all about colour and flash and dhishum and dhishkiyaon, and that’s mostly what the film turns out to be too. Much has already been said about Dhulia, a director of grounded hinterland stories with well-written characters, making a no-holds-barred commercial film, a “potboiler”. Normally I’m wary of such classifications, but after watching Bullett Raja I had to concede the point. This is a clear homage to the mainstream Hindi film of the 1970s and 80s. There is a Sholay reference early on (“Hamesha do kyon hote hain?” – “Why are there always two?” – grumbles a head villain whose men have been vanquished by Raja and Rudra), and the very presence of Gulshan Grover, Chunky Pandey and Raj Babbar (all of whom are reasonably well used, with Pandey hamming it up from behind red-tinted glasses) is a reminder of less sophisticated masala movies from times past. Bullett Raja reaches for the tone of those films without trying to be a cheeky, post-modern commentary on them; there is even a scene – filmed straight, without irony – involving the death of a loved one and the hero swearing vengeance through the flames of a funeral pyre.

Is it a good potboiler though? I’m not so sure. Though entertaining enough in patches, this is also an uneven, unfocused film, with too much going on at the same time. Characters flit in and out of sight, there are promising but not fully realised roles for Ravi Kishan and Vidyut Jamwal (as men who are, in different ways, Raja’s nemeses), and Sonakshi Sinha’s Mitali – the love interest – is no more than a random presence (though perhaps this too is a nod to the functional part heroines played in 1980s action movies). Some scene transitions are jarring, there are discontinuities and gaps in character development, the action sequences are confusing and go by before one can register what is happening. (Martial-arts star Jamwaldoes have a couple of good fight scenes, though one of them – a prolonged one involving a stealth attack on a gang of dacoits – plays more as a personal setpiece for him, having little to do with the main narrative.)

Is it a good potboiler though? I’m not so sure. Though entertaining enough in patches, this is also an uneven, unfocused film, with too much going on at the same time. Characters flit in and out of sight, there are promising but not fully realised roles for Ravi Kishan and Vidyut Jamwal (as men who are, in different ways, Raja’s nemeses), and Sonakshi Sinha’s Mitali – the love interest – is no more than a random presence (though perhaps this too is a nod to the functional part heroines played in 1980s action movies). Some scene transitions are jarring, there are discontinuities and gaps in character development, the action sequences are confusing and go by before one can register what is happening. (Martial-arts star Jamwaldoes have a couple of good fight scenes, though one of them – a prolonged one involving a stealth attack on a gang of dacoits – plays more as a personal setpiece for him, having little to do with the main narrative.)

Equally random are the film’s superficial excursions into political correctness, as in a scene involving a bellboy of Marathi origin and a little lesson about national unity. But then, Bullett Raja does unexpectedly become something of an India primer in its second half, first moving to Bombay for a bump-and-grind song in a posh pub, a view of skyscrapers and a glimpse of a film shoot involving Emraan Hashmi; then to Calcutta where Saif and Sonakshi romance against picturesque backdrops including Howrah Bridge and try to convince her sweet Bangla family of the seriousness of their relationship. In between, there is a trip to the Chambal Valley where we meet dakus (or baaghis) who dream of seeing Bipasha Basu dance while also dreaming of education and a better way of life for their children.

The world shown here then is one where modernity and older, more primal ways of life feed off each other. Feudal lines of power are very much in place, people in high positions spend time in jail purely for convenience and continue fixing deals – using Skype – while in their prison clothes; they speak in the salty dialects of their home town but nonchalantly break into English when you least expect it; meetings involving smartly dressed businessmen and politicians with their laptops take place in what seems the middle of a jungle. In this setting, it is always wise to touch the feet of hitmen, though you might – despite obligatory nods to piety and tradition – casually swat away a prasad-offering pandit who is interrupting an important conversation. And people, regardless of their origins, can be many things. Raja’s father, proud of their Brahmin ancestry, doesn’t want him to work in a hotel, washing other people’s jhootha dishes – but later we are reminded that “Brahmin rootha toh Ravana”. There are elderly men who are set in their hopelessly corrupt lifestyles (“Iss umar mein toh kaam badal nahin sakte” muses a businessman), and there are younger people who have more options available to them.

The world shown here then is one where modernity and older, more primal ways of life feed off each other. Feudal lines of power are very much in place, people in high positions spend time in jail purely for convenience and continue fixing deals – using Skype – while in their prison clothes; they speak in the salty dialects of their home town but nonchalantly break into English when you least expect it; meetings involving smartly dressed businessmen and politicians with their laptops take place in what seems the middle of a jungle. In this setting, it is always wise to touch the feet of hitmen, though you might – despite obligatory nods to piety and tradition – casually swat away a prasad-offering pandit who is interrupting an important conversation. And people, regardless of their origins, can be many things. Raja’s father, proud of their Brahmin ancestry, doesn’t want him to work in a hotel, washing other people’s jhootha dishes – but later we are reminded that “Brahmin rootha toh Ravana”. There are elderly men who are set in their hopelessly corrupt lifestyles (“Iss umar mein toh kaam badal nahin sakte” muses a businessman), and there are younger people who have more options available to them.

All this might have added up to subtle commentary on the many faces, divides and possibilities of a society, but that isn’t the kind of film Bullett Raja is trying to be. There is an inevitable reference in the Chambal scene to Dhulia’s Paan Singh Tomar, which was a much more restrained film about a man crossing over to the other side of the law and being unable to cross back. In a way, Bullett Rajais Paan Singh Lite or Paan Singh Happy. Escape and escapism are real possibilities here; they have to be, because a more commercial movie-making tradition requires the hero to be a survivor, so that an apparently tragic climax can later be revealed as something else altogether. Raja tells us at the very beginning that he has spent his life doing “aafat se aashiqui”. Expect him to do more of the same if there is a sequel, and to continue being as bullet-resistant as ever.

[A post about Dhulia's Paan Singh Tomar is here]

“Halka paani ya bhadkeela?” is the question with which the friendship between Raja Mishra (Saif Ali Khan) and Rudra (Jimmy Shergill) begins. The setting is a wedding party and Rudra is asking Raja if he is fine with the soft drink he has just been offered or if he wants something flashier, more potent. Raja opts for the latter, and he certainly gets it over the course of this noisy film. After a few hours of bonding over liquor, banter and an item girl, the two men expertly fight off an attack on the wedding house, and so their fate is sealed: they are subsequently drawn into the politics and mafia wars of the UP heartland. It is as if the simple act of drinking “bhadkeela paani” has engendered events that turn a regular, job-seeking boy into a superhero, a goonda or a “political commando” (depending on your perspective). Even as Raja and Rudra retain their goofiness and basic likability, the stakes will keep rising for them.

The opening credits of Tigmanshu Dhulia’s

Bullett Raja

are all about colour and flash and dhishum and dhishkiyaon, and that’s mostly what the film turns out to be too. Much has already been said about Dhulia, a director of grounded hinterland stories with well-written characters, making a no-holds-barred commercial film, a “potboiler”. Normally I’m wary of such classifications, but after watching Bullett Raja I had to concede the point. This is a clear homage to the mainstream Hindi film of the 1970s and 80s. There is a Sholay reference early on (“Hamesha do kyon hote hain?” – “Why are there always two?” – grumbles a head villain whose men have been vanquished by Raja and Rudra), and the very presence of Gulshan Grover, Chunky Pandey and Raj Babbar (all of whom are reasonably well used, with Pandey hamming it up from behind red-tinted glasses) is a reminder of less sophisticated masala movies from times past. Bullett Raja reaches for the tone of those films without trying to be a cheeky, post-modern commentary on them; there is even a scene – filmed straight, without irony – involving the death of a loved one and the hero swearing vengeance through the flames of a funeral pyre.

The opening credits of Tigmanshu Dhulia’s

Bullett Raja

are all about colour and flash and dhishum and dhishkiyaon, and that’s mostly what the film turns out to be too. Much has already been said about Dhulia, a director of grounded hinterland stories with well-written characters, making a no-holds-barred commercial film, a “potboiler”. Normally I’m wary of such classifications, but after watching Bullett Raja I had to concede the point. This is a clear homage to the mainstream Hindi film of the 1970s and 80s. There is a Sholay reference early on (“Hamesha do kyon hote hain?” – “Why are there always two?” – grumbles a head villain whose men have been vanquished by Raja and Rudra), and the very presence of Gulshan Grover, Chunky Pandey and Raj Babbar (all of whom are reasonably well used, with Pandey hamming it up from behind red-tinted glasses) is a reminder of less sophisticated masala movies from times past. Bullett Raja reaches for the tone of those films without trying to be a cheeky, post-modern commentary on them; there is even a scene – filmed straight, without irony – involving the death of a loved one and the hero swearing vengeance through the flames of a funeral pyre. Is it a good potboiler though? I’m not so sure. Though entertaining enough in patches, this is also an uneven, unfocused film, with too much going on at the same time. Characters flit in and out of sight, there are promising but not fully realised roles for Ravi Kishan and Vidyut Jamwal (as men who are, in different ways, Raja’s nemeses), and Sonakshi Sinha’s Mitali – the love interest – is no more than a random presence (though perhaps this too is a nod to the functional part heroines played in 1980s action movies). Some scene transitions are jarring, there are discontinuities and gaps in character development, the action sequences are confusing and go by before one can register what is happening. (Martial-arts star Jamwaldoes have a couple of good fight scenes, though one of them – a prolonged one involving a stealth attack on a gang of dacoits – plays more as a personal setpiece for him, having little to do with the main narrative.)

Is it a good potboiler though? I’m not so sure. Though entertaining enough in patches, this is also an uneven, unfocused film, with too much going on at the same time. Characters flit in and out of sight, there are promising but not fully realised roles for Ravi Kishan and Vidyut Jamwal (as men who are, in different ways, Raja’s nemeses), and Sonakshi Sinha’s Mitali – the love interest – is no more than a random presence (though perhaps this too is a nod to the functional part heroines played in 1980s action movies). Some scene transitions are jarring, there are discontinuities and gaps in character development, the action sequences are confusing and go by before one can register what is happening. (Martial-arts star Jamwaldoes have a couple of good fight scenes, though one of them – a prolonged one involving a stealth attack on a gang of dacoits – plays more as a personal setpiece for him, having little to do with the main narrative.) Equally random are the film’s superficial excursions into political correctness, as in a scene involving a bellboy of Marathi origin and a little lesson about national unity. But then, Bullett Raja does unexpectedly become something of an India primer in its second half, first moving to Bombay for a bump-and-grind song in a posh pub, a view of skyscrapers and a glimpse of a film shoot involving Emraan Hashmi; then to Calcutta where Saif and Sonakshi romance against picturesque backdrops including Howrah Bridge and try to convince her sweet Bangla family of the seriousness of their relationship. In between, there is a trip to the Chambal Valley where we meet dakus (or baaghis) who dream of seeing Bipasha Basu dance while also dreaming of education and a better way of life for their children.

The world shown here then is one where modernity and older, more primal ways of life feed off each other. Feudal lines of power are very much in place, people in high positions spend time in jail purely for convenience and continue fixing deals – using Skype – while in their prison clothes; they speak in the salty dialects of their home town but nonchalantly break into English when you least expect it; meetings involving smartly dressed businessmen and politicians with their laptops take place in what seems the middle of a jungle. In this setting, it is always wise to touch the feet of hitmen, though you might – despite obligatory nods to piety and tradition – casually swat away a prasad-offering pandit who is interrupting an important conversation. And people, regardless of their origins, can be many things. Raja’s father, proud of their Brahmin ancestry, doesn’t want him to work in a hotel, washing other people’s jhootha dishes – but later we are reminded that “Brahmin rootha toh Ravana”. There are elderly men who are set in their hopelessly corrupt lifestyles (“Iss umar mein toh kaam badal nahin sakte” muses a businessman), and there are younger people who have more options available to them.

The world shown here then is one where modernity and older, more primal ways of life feed off each other. Feudal lines of power are very much in place, people in high positions spend time in jail purely for convenience and continue fixing deals – using Skype – while in their prison clothes; they speak in the salty dialects of their home town but nonchalantly break into English when you least expect it; meetings involving smartly dressed businessmen and politicians with their laptops take place in what seems the middle of a jungle. In this setting, it is always wise to touch the feet of hitmen, though you might – despite obligatory nods to piety and tradition – casually swat away a prasad-offering pandit who is interrupting an important conversation. And people, regardless of their origins, can be many things. Raja’s father, proud of their Brahmin ancestry, doesn’t want him to work in a hotel, washing other people’s jhootha dishes – but later we are reminded that “Brahmin rootha toh Ravana”. There are elderly men who are set in their hopelessly corrupt lifestyles (“Iss umar mein toh kaam badal nahin sakte” muses a businessman), and there are younger people who have more options available to them.All this might have added up to subtle commentary on the many faces, divides and possibilities of a society, but that isn’t the kind of film Bullett Raja is trying to be. There is an inevitable reference in the Chambal scene to Dhulia’s Paan Singh Tomar, which was a much more restrained film about a man crossing over to the other side of the law and being unable to cross back. In a way, Bullett Rajais Paan Singh Lite or Paan Singh Happy. Escape and escapism are real possibilities here; they have to be, because a more commercial movie-making tradition requires the hero to be a survivor, so that an apparently tragic climax can later be revealed as something else altogether. Raja tells us at the very beginning that he has spent his life doing “aafat se aashiqui”. Expect him to do more of the same if there is a sequel, and to continue being as bullet-resistant as ever.

[A post about Dhulia's Paan Singh Tomar is here]

Published on November 28, 2013 23:45

November 25, 2013

Haathi ras - on an elephant trail

[From my Business Standard column, and a sort of extension of this post about animals in films]

“Just think – in India, you would be worshipped,” says William Gull, the royal doctor, to Joseph Merrick, a patient so severely deformed that he is mockingly known as the Elephant Man. The scene, depicting a fictional meeting between two real-life people in London in the late 1880s, is from one of my favourite books, the graphic novel From Hell . Gull is consoling the unhappy social outcast Merrick with a reference to Ganesha the elephant-headed God, but there is also a dark subtext, in the linking of a benevolent, twinkling, pleasingly rotund deity – the remover of obstacles – with a “mission” that leads to a long trail of blood in the streets of the East End. When Gull seeks the Elephant Man’s blessings later in the story, he is embarking on a very macabre act, one that most Ganesha-worshippers would decidedly not approve of!

Which may be a reminder that elephants can mean very different things to different people. (So can Gods, of course, and elephant-Gods.) A famous manifestation of an elephant as a blank slate is in the parable about a group of blind men, each with a very different idea of what the animal must look like. There is also Jose Saramago’s novel The Elephant’s Journey , in which an Indian elephant makes a long, dangerous journey from Portugal to Austria in the 16th century, becoming a symbol of what is possible, and inviting a range of perspectives from various observers.

A few days ago I attended a talk by the writer and academic Rachel Dwyer, about elephants in Indian cinema. Using stills and clips, Dwyer touched not just on relatively objective elephant depictions in such films as the 1937

Elephant Boy

(originally shot as a documentary, later re-edited into a narrative-driven feature) but also on such filmi archetypes as the “moral elephant” (the one pursing bad guy Pran through the jungles in the 1955 film

Munimji

) and the “secular elephant” – as in the ending of

Haathi Mere Saathi

, where the dead body of the elephant Ramu is taken on a sort of multi-religion pilgrimage, past a mandir, a masjid and a church.

A few days ago I attended a talk by the writer and academic Rachel Dwyer, about elephants in Indian cinema. Using stills and clips, Dwyer touched not just on relatively objective elephant depictions in such films as the 1937

Elephant Boy

(originally shot as a documentary, later re-edited into a narrative-driven feature) but also on such filmi archetypes as the “moral elephant” (the one pursing bad guy Pran through the jungles in the 1955 film

Munimji

) and the “secular elephant” – as in the ending of

Haathi Mere Saathi

, where the dead body of the elephant Ramu is taken on a sort of multi-religion pilgrimage, past a mandir, a masjid and a church. Many of us tend to patronise films like Haathi Mere Saathi these days. We laugh, or cringe, at some of the cheesier animal depictions from old Hindi cinema, such as the revenge-seeking dog Moti in Teri Meherbaniyan(sample of such mockery in this old piece), the resourceful, infant-rescuing hawk in Dharam Veer (But as Dwyer pointed out, there is also something immediate and moving about scenes like the one where a number of animals, including tigers, emerge from their cages to mourn Ramu’s death and there is a remarkable series of close-ups of animal and human faces. In this light, perhaps the most interesting part of the post-talk discussion was the idea that the use of animals in Indian art was rooted in a closeness to the pastoral way of life, where (as one attendee put it) “touching the skin of an animal” was a natural, desirable sensory experience, and where observing animals became a way for humans to understand or articulate their own feelings and relationships.

The only real way for humans to emotionally relate to an animal is by anthropomorphising, and we see this in our traditional storytelling forms that stress the interconnectedness of life, such as the Jataka Tales, about the Buddha’s animal forms, or the myths about Vishnu’s avatars, which blur the lines between God, human and animal. There may have been a natural transition from these forms of oral and written storytelling to the heightened emotions of Sanskrit and Parsi theatre, and thence to the distinct forms of expression in commercial cinema.

The only real way for humans to emotionally relate to an animal is by anthropomorphising, and we see this in our traditional storytelling forms that stress the interconnectedness of life, such as the Jataka Tales, about the Buddha’s animal forms, or the myths about Vishnu’s avatars, which blur the lines between God, human and animal. There may have been a natural transition from these forms of oral and written storytelling to the heightened emotions of Sanskrit and Parsi theatre, and thence to the distinct forms of expression in commercial cinema. And in this context, it is notable how a film like Haathi Mere Saathi – which, on the face of it, is just lightweight entertainment for children – stresses the importance of animals in the ideal of a “Pyaar ki Duniya” (the name given to the private zoo established by the Rajesh Khanna character) and even shows a distrust of sterile modernity, as represented by the big, flashy car that breaks down and has to be pushed by elephants in the film’s title song. As Dwyer pointed out, Ramu displays many of the emotions from the Indian tradition of navrasa, including shringaar (aesthetic appeal), karuna (compassion) and haasya (laughter). Elephants can be even bigger and more capacious than they first appear.

[Also see: this post about the birth of Ganesha and the bathroom battle; this one about elephant-headed transcribers in Ekta Kapoor's Mahabharata, and this one about Temple Grandin's book Animals in Translation. And some elephant photos from a Sri Lanka trip]

Published on November 25, 2013 22:29

November 20, 2013

Milky ways - the many faces of the Hindi-movie maa

[Here's the full text of the essay I did for Zubaan's anthology about motherhood. The book has plenty more in it, of course, including excellent pieces by Anita Roy, Manju Kapur, Shashi Deshpande and others. Look out for it - gift, spread the word etc.

Note: the "Motherly vignettes" section was meant to be a stand-alone thing, published either as a box or in different font, to mark it from the rest of the text, and perhaps to mirror the detours and interludes so often present in mainstream Hindi cinema. Didn't work out that way, but I've included it here]

-------------------------

Around the age of 14 I took what was meant to be a temporary break from Hindi cinema, and ended up staying away for over a decade. Years of relishing masala movies may have resulted in a form of dyspepsia – there had been too many overwrought emotions, too much dhishoom dhishoom, too much of the strictly regimented quantities of Drama and Action and Tragedy and Romance and Comedy that existed in almost every mainstream Hindi film of the time. Besides, I had developed a love for Old Hollywood, which would become a gateway to world cinema, and satellite TV had started making it possible to indulge such interests.

One of my catalysts for escape was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho , a film that is – among many other things – about a strange young man’s special relationship with his equally strange mother. I won’t bother with spoiler alerts for such a well-known pop-cultural artefact, so briefly: Norman Bates poisons his mom, preserves her body, walks around in her clothes and has conversations with himself in her voice. In his off-time, he murders young women as they shower.

None of this was a secret to me when I first saw the film, since a certain Psycho lore existed in my family. Years in advance, I had heard jokes about “mummification” from my own mummy – apparently, in the early 60s, her school-going brother had returned from a movie-hall and informed their startled mother that he wished to keep her body in a sitting position in the living room after she passed on.

Hitchcock’s film had a big effect on the way I watched and thought about movies, but I must admit that my own relationship with my mother was squarer than Norman’s. We quarrelled occasionally, but always in our own voices, and taxidermy did not obtrude upon our lives. Looking back, though, I think we could be described as unconventional in the context of the society we lived in. I was a single child, she was recently divorced, we had been through a lot together and were very close. But we were both – then, as now – private people, and so the relationship always respected personal space. We didn’t spend much time on small talk, we tended to stay in our own rooms for large parts of the day (and this is how it remains, as I type these words in my shabby freelancer’s “office” in her flat). Yet I always shared the really important stuff with her, and I never thought this was unusual until I heard stories about all the things my friends – even the ones from the seemingly cool, cosmopolitan families – routinely hid from their parents: about girlfriends, or bunking college, or their first cigarette.

Some of this may help explain why I was feeling detached from the emotional excesses of Hindi cinema in my early teens. In his book on Deewaar, the historian Vinay Lal notes, “No more important or poignant relationship exists in Indian society than that between mother and son, and the Hindi film best exemplifies the significance of this nexus.” That may be so, but I can say with my hand on my heart (or “mother-swear”, if you prefer) that even at age 14, I found little to relate to in Hindi-film depictions of mothers.

Some of this may help explain why I was feeling detached from the emotional excesses of Hindi cinema in my early teens. In his book on Deewaar, the historian Vinay Lal notes, “No more important or poignant relationship exists in Indian society than that between mother and son, and the Hindi film best exemplifies the significance of this nexus.” That may be so, but I can say with my hand on my heart (or “mother-swear”, if you prefer) that even at age 14, I found little to relate to in Hindi-film depictions of mothers.

Can you blame me though? Here, off the top of my head (and with only some basic research to confirm that I hadn’t dreamt up these wondrous things), are some of my movie memories from around the time I left the mandir of Hindi cinema:

* In the remarkably bad JamaiRaja , Hema Malini is a wealthy tyrant who makes life difficult for her son-in-law. Some of this is played for comedy, but the film clearly disapproves of the idea of a woman as the head of the house. Cosmic balance is restored only when the saas gets her comeuppance and asks the damaad’s forgiveness. Of course, he graciously clasps her joint hands and asks her not to embarrass him; that’s the hero’s privilege.

* In Sanjog , when she loses the little boy she had thought of as a son, Jaya Prada glides about in a white sari, holding a piece of wood wrapped in cloth and singing a song with the refrain “Zoo zoo zoo zoo zoo”. This song still plays incessantly in one of the darker rooms of my memory palace; I shudder whenever I recall the tune.

* In Aulad , the ubiquitous Jaya Prada is Yashoda who battles another woman (named, what else, Devaki) for custody of the bawling Baby Guddu, while obligatory Y-chromosome Jeetendra stands around looking smug and noble at the same time.

* In her short-lived comeback in Aandhiyan , a middle-aged Mumtaz dances with her screen son in a cringe-inducingly affected display of parental hipness. “Mother and son made a lovely love feeling with their dance and song (sic),” goes a comment on the YouTube video of the song “Duniya Mein Tere Siva”. Also: “I like the perfect matching mother and son love chemistry behind the song, it is a eternal blood equation (sic).” The quality of these comments is indistinguishable from the quality of the film they extol.

* And in

Doodh kaKarz

, a woman breastfeeding her child is so moved by the sight of a hungry cobra nearby that she squeezes a few drops of milk out and puts it in a bowl for him. The snake looks disgusted but sips some of the milk anyway. Naturally, this incident becomes the metaphorical umbilical cord that

* And in

Doodh kaKarz

, a woman breastfeeding her child is so moved by the sight of a hungry cobra nearby that she squeezes a few drops of milk out and puts it in a bowl for him. The snake looks disgusted but sips some of the milk anyway. Naturally, this incident becomes the metaphorical umbilical cord that

attaches him to this new maa for life.

attaches him to this new maa for life.

As one dire memory begets another, the title of that last film reminds me that two words were in common currency in 1980s Hindi cinema: “doodh” and “khoon”. Milk and blood. Since these twin fluids were central to every hyper-dramatic narrative about family honour and revenge, our movie halls (or video rooms, since few sensible people I knew spent money on theatre tickets at the time) resounded with some mix of the following proclamations:

“Maa ka doodh piya hai toh baahar nikal!” (“If you have drunk your mother’s milk, come out!”)

“Yeh tumhara apna khoon hai.” (“He is your own blood.”)

“Main tera khoon pee jaaoonga.” (“I will drink your blood.”)

Both liquids were treated as equally nourishing; both were, in different ways, symbols of the hero’s vitality. I have no recollection of the two words being used together in a sentence, but it would not amaze me to come across a scene from a 1980s relic where the hero says: “Kuttay! Maine apni maa ka doodh piya hai. Ab tera khoon piyoonga.” (“Dog! I have drunk my mother’s milk, now I will drink your blood.”) It would suggest a rite of passage consistent with our expectations of the über-macho lead: as a child you drink mother’s milk, but you’re all grown up now and bad man’s blood is more intoxicating than fake Johnnie Walker.

Both liquids were treated as equally nourishing; both were, in different ways, symbols of the hero’s vitality. I have no recollection of the two words being used together in a sentence, but it would not amaze me to come across a scene from a 1980s relic where the hero says: “Kuttay! Maine apni maa ka doodh piya hai. Ab tera khoon piyoonga.” (“Dog! I have drunk my mother’s milk, now I will drink your blood.”) It would suggest a rite of passage consistent with our expectations of the über-macho lead: as a child you drink mother’s milk, but you’re all grown up now and bad man’s blood is more intoxicating than fake Johnnie Walker.

Narcissists, angry young men and deadly guitars

All this is a complicated way of saying that I do not, broadly speaking, hold the 1980s in high esteem. But that decade is a soft target. Casting the net much wider, here’s a proposal: mainstream Hindi cinema has never had a sustained tradition of interesting mothers.

This is, of course, a generalisation; there have been exceptions in major films. Looming over every larger-than-life mother portrayal is Mother India, which invented (or at least highlighted) many of the things we think of as clichés today: the mother as metaphor for nation/land/nourishing source; the mother as righteous avenging angel, ready to shred her own heart and shoot her wayward son if it is for the Greater Good. Despite the self-conscious weightiness of this film’s narrative, it is - mostly - possible to see its central character Radha as an individual first and only then as a symbol.

But a basic problem is that for much of her history, the Hindi-film mother has been a cipher – someone with no real personality of her own, existing mainly as the prism through which we view the male lead. Much like the sisters whose function was to be raped and to commit suicide in a certain type of movie, the mother was a pretext for the playing out of the hero’s emotions and actions.

Anyone well acquainted with Hindi cinema knows that one of its dominant personalities has been the narcissistic leading man. (Note: the films themselves don’t intend him to be seen thus.) This quality is usually linked to the persona of the star-actor playing the role, and so it can take many forms: the jolly hero/tragic hero/romantic hero/anti-hero who ambles, trudges or swaggers through the world knowing full well that he is its centre of attention. (Presumably he never grew out of the maa ka laadla mould.) So here is Raj Kapoor’s little tramp smiling bravely through his hardships, and here is the studied tragic grandiosity of Dilip Kumar, and here is Dev Anand’s splendid conceit (visible in all the films he made from the mid-1960s on) that every woman from age 15 upwards wants only to fall into his arms. In later decades, this narcissism would be manifest in the leading man as the vigilante superhero.

A maa can easily become a foil for such personalities – our film history is dotted with sympathetic but ineffectual mothers. Though often played by accomplished character actors such as Achala Sachdev and Leela Mishra, these women were rarely central to the movies in question. If you have only a dim memory of Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa, for example, you might forget that the self-pitying poet (one of the most doggedly masochistic heroes in our cinema) has a mother too – she is a marginalised figure, watching with some perplexity as he wanders the streets waiting for life to deal him its next blow. And her death adds to the garland of sorrows that he so willingly carries around his neck.

A maa can easily become a foil for such personalities – our film history is dotted with sympathetic but ineffectual mothers. Though often played by accomplished character actors such as Achala Sachdev and Leela Mishra, these women were rarely central to the movies in question. If you have only a dim memory of Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa, for example, you might forget that the self-pitying poet (one of the most doggedly masochistic heroes in our cinema) has a mother too – she is a marginalised figure, watching with some perplexity as he wanders the streets waiting for life to deal him its next blow. And her death adds to the garland of sorrows that he so willingly carries around his neck.

While Dutt made a career out of not smiling, the protagonist of Raj Kapoor’s bloated Mera Naam Joker earned his livelihood by making people laugh. Essentially, however, Raju the clown is as much of a sympathy-seeker as the poet in the gutter is. Mera Naam Joker includes a magnificently maudlin scene where the joker continues with his act (“The show must go on!” growls circus-master Dharmendra) just a few minutes after learning that his mother has died. As he smiles heroically through his pain, his friends watching backstage wipe their tears – cues for the film’s viewer to do the same.

While Dutt made a career out of not smiling, the protagonist of Raj Kapoor’s bloated Mera Naam Joker earned his livelihood by making people laugh. Essentially, however, Raju the clown is as much of a sympathy-seeker as the poet in the gutter is. Mera Naam Joker includes a magnificently maudlin scene where the joker continues with his act (“The show must go on!” growls circus-master Dharmendra) just a few minutes after learning that his mother has died. As he smiles heroically through his pain, his friends watching backstage wipe their tears – cues for the film’s viewer to do the same.

Speaking of Raj Kapoor, I often wonder what impression Russian movie-watchers must have of Indian men and their mother fetishes. If Kapoor was the most popular Hindi-film star in the former Soviet Union, an improbable second was Mithun Chakraborty, the stature of whose 1982 film Disco Dancer in that part of the world is among the profoundest cinematic mysteries. (Possibly apocryphal stories are still told about how Indian visitors to the USSR in the Iron Curtain days could clear borders by warbling “Jimmy Jimmy” whereupon stern guards would drop their rifles and wave them through.)

Among Disco Dancer’s many pleasures is the most thrilling mother-related dialogue in a Hindi film. Even today, I would walk many a harsh mile to hear the following words echoing through a movie hall: “Issko guitar phobia ho gaya hai. Guitar ne isske maa ko maara.” (“He has developed guitar phobia. A guitar killed his mother.”)

This demands some elucidation. Jimmy (Mithun) has become so popular that his disco-dancing rivals scheme to electrocute him with a 5000-volt current. But his widowed maa, having just finished her daily puja for his continued health and success, learns about this fiendish saazish. She reaches the venue in time to grab the tampered guitar before Jimmy does, which results in the most electrifying death scene of a Hindi-movie mother you’ll ever see.

The subtext to this surreal moment is that the hero is emasculated by the removal of his mother. As one inadvertently Oedipal plot synopsis I have read puts it, “After his mother's death Jimmy finds himself unable to perform. Will he be able to recover from the tragedy and start performing again?” (Note the contrast with Mera Naam Joker’s Raju, who does indeed “perform” just a few seconds after his loss – but no one doubts that he is now a hollow shell of a person.)

As these scenes and countless others indicate, Hindi cinema loves dead moms. In the same year as Disco Dancer, there was an overhyped “acting battle” between Dilip Kumar and Amitabh Bachchan in Shakti. It played out through the film, but never as intensely as in the scene where the mutinous son tries to reach out to his policeman dad in the room where the dead body of Sheetal (wife and mother to the two men) lies. In the context of the narrative, the mother’s corpse becomes the final frontier for a clash of ideologies and life experiences.

****

I’m surprised at how long it has taken me to arrive at Bachchan, given that all my early movie-watching centred on him – and also given that no other major Hindi-film personality has been as strongly associated with filial relationships. But perhaps I’ve been trying to repress a memory. One of the last things I saw before forsaking Bollywood in 1991 was this scene from the fantasy film Ajooba. Bachchan (makeup doing little to conceal that he was playing half his age) brings an old woman to the seaside where a dolphin is splashing about, beaming and making the sounds that dolphins will. With sonly fondness in his eyes and a scant regard for taxonomical accuracy, AB says: “Yeh machli meri maa hai.” (“This fish is my mother.”)

This could be a version of post-modern irony, for Bachchan had come a long way from the star-making films in which he played son to the long-suffering Nirupa Roy. Unlike the “mother” in Ajooba, Roy was a land mammal, but she seemed always to have a personal lake of tears to splash about in at short notice.

This could be a version of post-modern irony, for Bachchan had come a long way from the star-making films in which he played son to the long-suffering Nirupa Roy. Unlike the “mother” in Ajooba, Roy was a land mammal, but she seemed always to have a personal lake of tears to splash about in at short notice.

Was that too irreverent? (Am I failing the test of the good Indian boy whose eyes must lower at the very mention of “maa”?) Well, respect should ideally be earned. The mothers played by Roy are good examples of the ciphers I mentioned earlier, and though she often got substantial screen time, I don’t think it was put to much good use.

Consider an early scene in Prakash Mehra’s Muqaddar ka Sikander. When the orphan Sikander recovers Roy’s stolen purse for her, she expresses a wish to be his new mother: “Beta, ab se main tumhari maa hoon.” “Sach, maa? Tum bahut achi ho, maa,” (“Really, mother? You are very nice, mother”) he replies. Having rushed through these lines, they then exit the frame together in the jerky fast-forward style of the silent era’s Keystone Kops. There is a reason for the haste: the audience wants to see the adult Sikander (Bachchan), so the preamble must be dispensed with. But the result is the trivialising of an important relationship – we are simply told that they are now mother and son, and that’s that. It’s a good example of character development scrubbing the shoes of the star system.

Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony is another movie very dear to my heart (and a genuine classic of popular storytelling), but it would be a stretch to claim that Roy’s Bharati (you know, the woman who simultaneously receives blood from her three grown-up sons) is a fleshed-out person. Medically speaking, she scarcely appears human at all: in the first minutes of the film we learn that Bharati is suffering from life-threatening tuberculosis; a while later, she carelessly loses her eyesight and the TB is never again mentioned; years pass and here she is, distributing flowers, haphazardly stumbling in and out of the lives of the three heroes; eventually her sight is restored by a Sai Baba statue.

But it is well-nigh impossible to write about Bachchan and his mothers without reference to Yash Chopra’ sDeewaar (and to an extent, the same director’s Trishul). Deewaar is to Hindi cinema what the James Cagney-starrer White Heat (“Made it, Ma! Top of the world!”) was to Hollywood: the most quoted and parodied of all mother-son movies. In no small part this is because the film was a fulcrum for one of our most iconic movie personalities, the angry young man Vijay.

Speaking for myself, childhood memory and countless spoofs on music channels had turned Deewaarinto a montage of famous images and dialogues: Bachchan brooding outside the temple; a dramatic pealing of bells and a prolonged death scene; Shashi Kapoor bleating “Bhai” and, with nostrils flaring self-righteously, the famous line “Mere Paas Maa Hai.” But when I saw it as an adult, I was surprised by how powerful the film still was, and how its most effective scenes were the quieter ones. One scene that sticks with me is when the mother – Sumitra Devi – is unwell and the fugitive Vijay can’t see her because police have been posted around the hospital. He waits in a van while his girlfriend goes to check on the level of security. She returns, tells him things aren’t looking good; and Vijay (who is wearing dark glasses – a chilling touch in this night-time scene) says in a deadpan voice, his face a blank slate, “Aur main apne maa tak nahin pahunch sakta hoon.” (“And I can’t even reach my mother.”) There is no overt attempt at pathos or irony (how many other Indian actors of the time would have played the scene this way?), just the stoicism of a man who knows that the walls are closing in.

In another scene Vijay hesitantly calls his mother on the phone, arranges to meet her at the temple, then tries to say something more but can’t get the words out and puts the receiver down instead. The film’s power draws as much from these discerning beats of silence as from its flaming Salim-Javed dialogue. However, little of that power comes directly from the mother’s character. Sumitra Devi is defined by her two sons, and to my eyes at least, there is something perfunctory and insipid even about the moral strength she shows.

There is a tendency, when we assess Hindi cinema, to make sweeping statements about similar types of movies. Frequently, I hear that Deewaar and Trishul are the same film because both are built around the theme of a son trying to erase his mother’s sufferings by rising in the world – even literally, by signing deed papers for new skyscrapers, the constructions she once worked on as a labourer (Vijay, like James Cagney, is trying to make it to “the top”). But there are key differences in the central character’s motivations in the two movies, and I would argue that Deewaar is the superior film overall because it is more tightly constructed.

There is a tendency, when we assess Hindi cinema, to make sweeping statements about similar types of movies. Frequently, I hear that Deewaar and Trishul are the same film because both are built around the theme of a son trying to erase his mother’s sufferings by rising in the world – even literally, by signing deed papers for new skyscrapers, the constructions she once worked on as a labourer (Vijay, like James Cagney, is trying to make it to “the top”). But there are key differences in the central character’s motivations in the two movies, and I would argue that Deewaar is the superior film overall because it is more tightly constructed.

However, Trishulscores in one important regard: it is one of the few Bachchan films where the mother has a personality. Cynically speaking, this could be because she dies early in the film and isn’t required to hold the stage for three hours, but I think it has a lot to do with the performance of Waheeda Rehman – an actress who made a career of illuminating mediocre movies with her presence.

“Tu mere saath rahega munne,” sings this mother, who has been abandoned by her lover – the song will echo through the movie and fuel her son’s actions. “Main tujhe rehem ke saaye mein na palne doongi” (“I will not raise you under the shade of sympathy”), she tells her little boy as she lets him toil alongside her, “Zindagani ki kadi dhoop mein jalne doongi / Taake tap tap ke tu faulad bane / maa ki audlad bane.” She wants him to burn in the sun so he becomes as hard as steel. He has to earn his credentials if he wants the right to be called her son.

With a lesser performer in the role, this could have been hackneyed stuff (in any case the basic premise is at least as old as Raj Kapoor’s Awaara), but Rehman makes it dignified and compelling, giving it a psychological dimension that is lacking in all those Nirupa Roy roles. It’s a reminder that an excellent performer can, to some extent at least, redeem an unremarkable part. (I would make a similar case for Durga Khote in Mughal-e Azam, which – on paper at least – was a film about two imperial male egos in opposition.)

Motherly vignettes (and an absence)

In discussing these films, I’ve probably revealed my ambivalence towards popular Hindi cinema. One problem for someone who tries to engage with these films is that even the best of them tend to be disjointed; a critic is often required to approach a movie as a collection of parts rather than as a unified whole. Perhaps it would be fair then to admit that there have been certain “mother moments” that worked for me on their own terms, independently of the overall quality of the films.

One of them occurred in – of all things – a Manoj Kumar film. Kumar was famous for his motherland-obsession, demonstrated in a series of “patriotic” films that often exploited their heroines. (See Hema Malini writhing in the rain in Kranti, or Saira Banu in Purab aur Paschim, subject to the controlling male gaze that insists a woman must be covered up – after the hero and the audience has had a good eyeful, of course.) But one of his rare non-patriotism-themed films contains a weirdly compelling representation of the mother-as-an-absent-presence. The film is the 1972 Shor, about a boy so traumatised by his mother’s death that he loses his speech, and the song is the plaintive Laxmikant-Pyarelal composition “Ek Pyaar ka Nagma Hai”.

In too many Hindi movies of that time, ethereal music is played out to banal images, but this sequence makes at least a theoretical nod to creativity. The visuals take the shape of a shared dream-memory involving the father, the little boy and the mother when she was alive; the setting is a beach and the composite elements include a violin, a drifting, symbolism-laden bunch of balloons, and Nanda. Mirror imagery is used: almost every time we see the mother or the boy, we also see their blurred reflections occupying half the screen; occasionally, the lens focus is tinkered with to make both images merge into each other or disappear altogether. Even though the setting is ostensibly a happy and “realist” one, Nanda is thus rendered a distant, ghostly figure.

In too many Hindi movies of that time, ethereal music is played out to banal images, but this sequence makes at least a theoretical nod to creativity. The visuals take the shape of a shared dream-memory involving the father, the little boy and the mother when she was alive; the setting is a beach and the composite elements include a violin, a drifting, symbolism-laden bunch of balloons, and Nanda. Mirror imagery is used: almost every time we see the mother or the boy, we also see their blurred reflections occupying half the screen; occasionally, the lens focus is tinkered with to make both images merge into each other or disappear altogether. Even though the setting is ostensibly a happy and “realist” one, Nanda is thus rendered a distant, ghostly figure.

I’m not saying this is done with anything resembling sophistication – it is at best an ambitious concept, shoddily executed; you can sense the director and cinematographer constrained by the available technology. But the basic idea does come through: what we are seeing is a merging of past and present, and the dislocation felt by a motherless child.

[While on absent mothers, a quick aside on Sholay. Ramesh Sippy’s iconic film was heavily inspired by the look of the American and Italian Westerns, but it also deviated from the Hindi-film idiom in one significant way: in the absence of a mother-child relationship. The only real mother figure in the story, Basanti’s sceptical maasi, becomes a target of mirth in one of the film’s drollest scenes. Most notably, the two leads Veeru and Jai (played by Dharmendra and Bachchan) are orphans who have only ever had each other. We tend to take Sholay for granted today, but it’s surprising, when you think about it, that the leading men of a Hindi movie of the time should so summarily lack any maternal figure, real or adopted.]

In Vijay Anand’s thriller Jewel Thief, a clever deception is perpetrated on the viewer. Early on, Vinay (Dev Anand) is told that Shalu (Vyjayantimala) is pining because she has been abandoned by her fiancé. This provides a set-up for the song “Rula ke Gaya Sapna Mera”, where Vinay hears Shalu singing late at night; we see her dressed in white, weeping quietly; the lyrics mourn her loss; our expectations from seeing Dev Anand and Vyjayantimala together in this romantic setting lead us to assume that what is being lamented is a broken love affair. But later, we learn that though Shalu’s tears were genuine, she was really crying for a little boy who has been kidnapped (this is, strictly speaking, her much younger brother, but the relationship is closer to that of a mother and son, and the song was an expression if it). It’s a rare example of a Hindi-movie song sequence being used to mislead, and changing its meaning when you revisit it.

In Vijay Anand’s thriller Jewel Thief, a clever deception is perpetrated on the viewer. Early on, Vinay (Dev Anand) is told that Shalu (Vyjayantimala) is pining because she has been abandoned by her fiancé. This provides a set-up for the song “Rula ke Gaya Sapna Mera”, where Vinay hears Shalu singing late at night; we see her dressed in white, weeping quietly; the lyrics mourn her loss; our expectations from seeing Dev Anand and Vyjayantimala together in this romantic setting lead us to assume that what is being lamented is a broken love affair. But later, we learn that though Shalu’s tears were genuine, she was really crying for a little boy who has been kidnapped (this is, strictly speaking, her much younger brother, but the relationship is closer to that of a mother and son, and the song was an expression if it). It’s a rare example of a Hindi-movie song sequence being used to mislead, and changing its meaning when you revisit it.

There is also a lovely little scene in a non-mainstream Hindi film, Sudhir Mishra’s Dharavi . Cab-driver Rajkaran, his wife and little son are struggling to make ends meet as one mishap follows another. Rajkaran’s old mother has come to visit them in the city and one night, after a series of events that leaves the family bone-tired and mentally exhausted, there is a brief shot of two pairs of sons and mothers, with the former curled up with their heads in the latter’s laps – the grown-up Rajkaran is in the same near-foetal pose as his little boy. It’s the sort of image that captures a relationship more eloquently than pages of over-expository script.

Breaking the weepie mould: new directions

One of the funniest mothers in a Hindi film was someone who appeared only in a photograph – the madcap 1962 comedy Half Ticket has a scene where the protagonist Vijay (no relation to the Angry Young Man) speaks to a picture of his tuberculosis-afflicted mother. TB-afflicted mothers are usually no laughing matter in Hindi cinema, but this is a Kishore Kumar film, and thus it is that a close-up of the mother’s photo reveals ... Kishore Kumar in drag. This could be a little nod to Alec Guinness and Peter Sellers playing women in Ealing Studio comedies of the 50s, or it could be a case of pre-figuring (since the story will hinge on Kumar posing as a child). Either way, it is a rare instance in old cinema of a mother being treated with light-hearted irreverence.

But as mentioned earlier, the more characteristic mother treatment has been one of deification – which, ironically, results in diminishment. When the maternal figure is put on a pedestal, you don’t see her as someone with flaws, whimsies, or heaven forbid, an interior life. (One of Indian cinema’s starkest treatments of this theme was in Satyajit Ray’s 1960 film

Devi

, with the 14-year-old Sharmila Tagore as a bride whose world turns upside down when her childlike father-in-law proclaims her a reincarnation of the Mother Goddess.) And so, if there has been a shift in mother portrayals in recent times, it has hinged on a willingness to humanise.

a pedestal, you don’t see her as someone with flaws, whimsies, or heaven forbid, an interior life. (One of Indian cinema’s starkest treatments of this theme was in Satyajit Ray’s 1960 film

Devi

, with the 14-year-old Sharmila Tagore as a bride whose world turns upside down when her childlike father-in-law proclaims her a reincarnation of the Mother Goddess.) And so, if there has been a shift in mother portrayals in recent times, it has hinged on a willingness to humanise.

Around the late 1980s, a certain sort of “liberal” movie mum had come into being. I remember nodding in appreciation at the scene in Maine Pyaar Kiya where Prem (Salman Khan) discusses prospective girlfriends with his mom (played by the always-likeable Reema Lagoo). Still, when it came to the crunch, you wouldn’t expect these seemingly broad-minded women to do anything that would seriously shake the patriarchal tradition. In her younger days Farida Jalal was among the feistiest of the actresses who somehow never became A-grade stars, but by the time she played Kajol’s mother in Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jaayenge, she had settled into the role of the woman who can feel for young love – and be a friend and confidant to her daughter – while also knowing, through personal experience, that women in her social setup “don’t even have the right to make promises”. The two young lovers in this film can be united only when the heart of the stern father melts.

discusses prospective girlfriends with his mom (played by the always-likeable Reema Lagoo). Still, when it came to the crunch, you wouldn’t expect these seemingly broad-minded women to do anything that would seriously shake the patriarchal tradition. In her younger days Farida Jalal was among the feistiest of the actresses who somehow never became A-grade stars, but by the time she played Kajol’s mother in Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jaayenge, she had settled into the role of the woman who can feel for young love – and be a friend and confidant to her daughter – while also knowing, through personal experience, that women in her social setup “don’t even have the right to make promises”. The two young lovers in this film can be united only when the heart of the stern father melts.

Such representations – mothers as upholders of “traditional values”, even when those values are detrimental to the interests of women – are not going away any time soon, and why would they, if cinema is to be a part-mirror to society? An amusing motif in the 2011 film No One Killed Jessica was a middle-aged mother as a figure hiding behind the curtain (literally “in pardah”), listening to the men’s conversations and speaking up only to petulantly demand the return of her son (who is on the lam, having cold-bloodedly murdered a young woman). It seems caricatured at first, but when you remember the details of the real-life Jessica Lal-Manu Sharma case that the film is based on, there is nothing surprising about it .

But it is also true that in the multiplex era of the last decade, mother representations – especially in films with urban settings – have been more varied than they were in the past. (Would it be going too far to say “truer to life”? I do feel that the best contemporary Hindi films are shaped by directors and screenwriters who know their milieus and characters very well, and have a greater willingness to tackle individual complexity than many of their predecessors did.)

Thus, Jaane Tu...Ya Jaane Na featured a terrific performance by Ratna Pathak Shah as Savitri Rathore, a wisecracking mom whose banter with her dead husband’s wall-portrait marks a 180-degree twist on every maudlin wall-portrait scene from movies of an earlier time. (Remember the weepy monologues that went “Munna ab BA Pass ho gaya hai. Aaj agar aap hamaare saath hote, aap itne khush hote”?) One gets the sense that unlike her mythological namesake, this Savitri is relieved that she no longer has to put up with her husband’s three-dimensional presence! Then there is the Kirron Kher character in Dostana, much more orthodox to begin with: a jokily over-the-top song sequence, “Maa da laadla bigad gaya”, portrays her dismay about the possibility that her son is homosexual, and she is even shown performing witchery to “cure” him. But she does eventually come around, gifting bangles to her “daughter-in-law” and wondering if traditional Indian rituals might accommodate something as alien as gay marriage. These scenes are played for laughs (and in any case, the son isn’t really gay), but they do briefly touch on very real cultural conflicts and on the ways in which parents from conservative backgrounds often have to change to keep up with the times.

presence! Then there is the Kirron Kher character in Dostana, much more orthodox to begin with: a jokily over-the-top song sequence, “Maa da laadla bigad gaya”, portrays her dismay about the possibility that her son is homosexual, and she is even shown performing witchery to “cure” him. But she does eventually come around, gifting bangles to her “daughter-in-law” and wondering if traditional Indian rituals might accommodate something as alien as gay marriage. These scenes are played for laughs (and in any case, the son isn’t really gay), but they do briefly touch on very real cultural conflicts and on the ways in which parents from conservative backgrounds often have to change to keep up with the times.

With the aid of nuanced scripts, thoughtful casting and good performances, other small bridges have been crossed in recent years. Taare Zameen Par – the story of a dyslexic child – contains an uncontrived depiction of the emotional bond between mother and child (as well as the beautiful song “Maa”). At age 64, Bachchan acquired one of his most entertaining screen moms, the then 94-year-old Zohra Segal, in R Balki’s Cheeni Kum. A few years after that, the somewhat gimmicky decision to cast him as a Progeria-afflicted child in Paa meant he could play son to Vidya Balan, who was less than half his age. There is quiet dignity in this portrayal of a single working mother, though the film did kowtow to tradition (and to the ideal of the romantic couple) by ensuring that she is reunited with her former lover at the end.

One of the last Hindi films I saw before writing this piece – another Balan-starrer, the thriller Kahaani – has as its protagonist a heavily pregnant woman alone in the city, searching for her missing husband. This makes for an interesting psychological study because the quality of the film’s suspense (and the effect of the twist in its tail) depends on our accumulating feelings – sympathy, admiration – for this mother-to-be, laced with the mild suspicion that we mustn’t take everything about her at face value. I wasn’t surprised to discover that some people felt a little betrayed (read: emotionally manipulated) by the ending, which reveals that Vidya Bagchi wasn’t pregnant after all – the revelation flies in the face of everything Hindi cinema has taught us about the sanctity of motherhood.

****

Given Vinay Lal’s observation about the centrality of the mother-son relationship in Indian society, it is perhaps inevitable that our films have a much more slender tradition of mother-daughter relationships. Going by all the gossip over the decades about dominating moms accompanying their starlet daughters to movie sets, the real-life stories may have been spicier than anything depicted on screen. And in fact, one of the scariest scenes from any Hindi film of the last decade involves just such a portrayal.

It occurs in Zoya Akhtar’s excellent

Luck by Chance

, a self-reflective commentary on the nature of stardom in Hindi cinema. The young rose Nikki Walia (Isha Sharvani) is doing one of those cutesy photo shoot-cum-interviews that entail completing sentences like “My favourite colour is ____.” At one point her mother Neena (Dimple Kapadia in an outstanding late-career performance), a former movie star herself, barges into the room and peremptorily begins giving instructions. We see Nikki’s expression (we have already noted how cowered she is by her mother’s presence) and feel a little sorry for her. “Neena-ji, can we have a photo of both of you?” the reporter asks. Neena-ji looks flattered but says no, she isn’t in a state fit to be photographed – why don’t you shoot Nikki against that wall, she says, pointing somewhere off-screen, and then sashaying off.

It occurs in Zoya Akhtar’s excellent

Luck by Chance

, a self-reflective commentary on the nature of stardom in Hindi cinema. The young rose Nikki Walia (Isha Sharvani) is doing one of those cutesy photo shoot-cum-interviews that entail completing sentences like “My favourite colour is ____.” At one point her mother Neena (Dimple Kapadia in an outstanding late-career performance), a former movie star herself, barges into the room and peremptorily begins giving instructions. We see Nikki’s expression (we have already noted how cowered she is by her mother’s presence) and feel a little sorry for her. “Neena-ji, can we have a photo of both of you?” the reporter asks. Neena-ji looks flattered but says no, she isn’t in a state fit to be photographed – why don’t you shoot Nikki against that wall, she says, pointing somewhere off-screen, and then sashaying off.

A few seconds later the shoot continues. “Your favourite person _____?” Nikki is asked. We get a full shot of the wall behind her – it is covered end to end with a colossal photo of Neena from her early days. “My mother,” Nikki replies mechanically.

The younger Kapadia in that photo is breathtakingly beautiful, but as a depiction of a child swallowed up by a parent’s personality, this brief shot is just as terrifying to my eyes as the closing scene of Psycho, with Norman Bates staring out at the camera, speaking to us in his mother’s voice – for all practical purposes, back in the womb. Luck by Chance contains other scenes suggesting that the predatorial Neena is bent on putting her daughter through everything she herself had experienced in the big bad industry. Do these scenes get additional power from the viewer’s non-diagetic knowledge that in real life, Dimple Kapadia herself entered the film industry at a disturbingly early age? You decide. Still, with the history of mainstream Hindi cinema being what it is, we should be grateful for this newfound variety, for stronger character development, and for at least some maternal representations that aren’t drenched in sentimentalism.

We’ve always had the noble, self-sacrificing and marginalised mothers and we’ll continue to have them – in cinema, as in life. So here’s to a few more of the other sorts: more Neena-jis, more sardonic Savitris, a few moms like the hard-drinking salon-owner in Vicky Donor , not-really-mothers like Vidya Bagchi – and even, if it ever comes to that, a desi Mrs Bates staring unblinkingly from her chair, asking her son to please go to the kitchen and make her some chai instead of ogling at chaalu young women through the peephole.

Note: the "Motherly vignettes" section was meant to be a stand-alone thing, published either as a box or in different font, to mark it from the rest of the text, and perhaps to mirror the detours and interludes so often present in mainstream Hindi cinema. Didn't work out that way, but I've included it here]

-------------------------

Around the age of 14 I took what was meant to be a temporary break from Hindi cinema, and ended up staying away for over a decade. Years of relishing masala movies may have resulted in a form of dyspepsia – there had been too many overwrought emotions, too much dhishoom dhishoom, too much of the strictly regimented quantities of Drama and Action and Tragedy and Romance and Comedy that existed in almost every mainstream Hindi film of the time. Besides, I had developed a love for Old Hollywood, which would become a gateway to world cinema, and satellite TV had started making it possible to indulge such interests.

One of my catalysts for escape was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho , a film that is – among many other things – about a strange young man’s special relationship with his equally strange mother. I won’t bother with spoiler alerts for such a well-known pop-cultural artefact, so briefly: Norman Bates poisons his mom, preserves her body, walks around in her clothes and has conversations with himself in her voice. In his off-time, he murders young women as they shower.

None of this was a secret to me when I first saw the film, since a certain Psycho lore existed in my family. Years in advance, I had heard jokes about “mummification” from my own mummy – apparently, in the early 60s, her school-going brother had returned from a movie-hall and informed their startled mother that he wished to keep her body in a sitting position in the living room after she passed on.

Hitchcock’s film had a big effect on the way I watched and thought about movies, but I must admit that my own relationship with my mother was squarer than Norman’s. We quarrelled occasionally, but always in our own voices, and taxidermy did not obtrude upon our lives. Looking back, though, I think we could be described as unconventional in the context of the society we lived in. I was a single child, she was recently divorced, we had been through a lot together and were very close. But we were both – then, as now – private people, and so the relationship always respected personal space. We didn’t spend much time on small talk, we tended to stay in our own rooms for large parts of the day (and this is how it remains, as I type these words in my shabby freelancer’s “office” in her flat). Yet I always shared the really important stuff with her, and I never thought this was unusual until I heard stories about all the things my friends – even the ones from the seemingly cool, cosmopolitan families – routinely hid from their parents: about girlfriends, or bunking college, or their first cigarette.

Some of this may help explain why I was feeling detached from the emotional excesses of Hindi cinema in my early teens. In his book on Deewaar, the historian Vinay Lal notes, “No more important or poignant relationship exists in Indian society than that between mother and son, and the Hindi film best exemplifies the significance of this nexus.” That may be so, but I can say with my hand on my heart (or “mother-swear”, if you prefer) that even at age 14, I found little to relate to in Hindi-film depictions of mothers.

Some of this may help explain why I was feeling detached from the emotional excesses of Hindi cinema in my early teens. In his book on Deewaar, the historian Vinay Lal notes, “No more important or poignant relationship exists in Indian society than that between mother and son, and the Hindi film best exemplifies the significance of this nexus.” That may be so, but I can say with my hand on my heart (or “mother-swear”, if you prefer) that even at age 14, I found little to relate to in Hindi-film depictions of mothers.Can you blame me though? Here, off the top of my head (and with only some basic research to confirm that I hadn’t dreamt up these wondrous things), are some of my movie memories from around the time I left the mandir of Hindi cinema:

* In the remarkably bad JamaiRaja , Hema Malini is a wealthy tyrant who makes life difficult for her son-in-law. Some of this is played for comedy, but the film clearly disapproves of the idea of a woman as the head of the house. Cosmic balance is restored only when the saas gets her comeuppance and asks the damaad’s forgiveness. Of course, he graciously clasps her joint hands and asks her not to embarrass him; that’s the hero’s privilege.

* In Sanjog , when she loses the little boy she had thought of as a son, Jaya Prada glides about in a white sari, holding a piece of wood wrapped in cloth and singing a song with the refrain “Zoo zoo zoo zoo zoo”. This song still plays incessantly in one of the darker rooms of my memory palace; I shudder whenever I recall the tune.

* In Aulad , the ubiquitous Jaya Prada is Yashoda who battles another woman (named, what else, Devaki) for custody of the bawling Baby Guddu, while obligatory Y-chromosome Jeetendra stands around looking smug and noble at the same time.

* In her short-lived comeback in Aandhiyan , a middle-aged Mumtaz dances with her screen son in a cringe-inducingly affected display of parental hipness. “Mother and son made a lovely love feeling with their dance and song (sic),” goes a comment on the YouTube video of the song “Duniya Mein Tere Siva”. Also: “I like the perfect matching mother and son love chemistry behind the song, it is a eternal blood equation (sic).” The quality of these comments is indistinguishable from the quality of the film they extol.

* And in

Doodh kaKarz

, a woman breastfeeding her child is so moved by the sight of a hungry cobra nearby that she squeezes a few drops of milk out and puts it in a bowl for him. The snake looks disgusted but sips some of the milk anyway. Naturally, this incident becomes the metaphorical umbilical cord that

* And in

Doodh kaKarz

, a woman breastfeeding her child is so moved by the sight of a hungry cobra nearby that she squeezes a few drops of milk out and puts it in a bowl for him. The snake looks disgusted but sips some of the milk anyway. Naturally, this incident becomes the metaphorical umbilical cord that

attaches him to this new maa for life.

attaches him to this new maa for life.As one dire memory begets another, the title of that last film reminds me that two words were in common currency in 1980s Hindi cinema: “doodh” and “khoon”. Milk and blood. Since these twin fluids were central to every hyper-dramatic narrative about family honour and revenge, our movie halls (or video rooms, since few sensible people I knew spent money on theatre tickets at the time) resounded with some mix of the following proclamations:

“Maa ka doodh piya hai toh baahar nikal!” (“If you have drunk your mother’s milk, come out!”)

“Yeh tumhara apna khoon hai.” (“He is your own blood.”)

“Main tera khoon pee jaaoonga.” (“I will drink your blood.”)

Both liquids were treated as equally nourishing; both were, in different ways, symbols of the hero’s vitality. I have no recollection of the two words being used together in a sentence, but it would not amaze me to come across a scene from a 1980s relic where the hero says: “Kuttay! Maine apni maa ka doodh piya hai. Ab tera khoon piyoonga.” (“Dog! I have drunk my mother’s milk, now I will drink your blood.”) It would suggest a rite of passage consistent with our expectations of the über-macho lead: as a child you drink mother’s milk, but you’re all grown up now and bad man’s blood is more intoxicating than fake Johnnie Walker.

Both liquids were treated as equally nourishing; both were, in different ways, symbols of the hero’s vitality. I have no recollection of the two words being used together in a sentence, but it would not amaze me to come across a scene from a 1980s relic where the hero says: “Kuttay! Maine apni maa ka doodh piya hai. Ab tera khoon piyoonga.” (“Dog! I have drunk my mother’s milk, now I will drink your blood.”) It would suggest a rite of passage consistent with our expectations of the über-macho lead: as a child you drink mother’s milk, but you’re all grown up now and bad man’s blood is more intoxicating than fake Johnnie Walker. Narcissists, angry young men and deadly guitars

All this is a complicated way of saying that I do not, broadly speaking, hold the 1980s in high esteem. But that decade is a soft target. Casting the net much wider, here’s a proposal: mainstream Hindi cinema has never had a sustained tradition of interesting mothers.

This is, of course, a generalisation; there have been exceptions in major films. Looming over every larger-than-life mother portrayal is Mother India, which invented (or at least highlighted) many of the things we think of as clichés today: the mother as metaphor for nation/land/nourishing source; the mother as righteous avenging angel, ready to shred her own heart and shoot her wayward son if it is for the Greater Good. Despite the self-conscious weightiness of this film’s narrative, it is - mostly - possible to see its central character Radha as an individual first and only then as a symbol.

But a basic problem is that for much of her history, the Hindi-film mother has been a cipher – someone with no real personality of her own, existing mainly as the prism through which we view the male lead. Much like the sisters whose function was to be raped and to commit suicide in a certain type of movie, the mother was a pretext for the playing out of the hero’s emotions and actions.

Anyone well acquainted with Hindi cinema knows that one of its dominant personalities has been the narcissistic leading man. (Note: the films themselves don’t intend him to be seen thus.) This quality is usually linked to the persona of the star-actor playing the role, and so it can take many forms: the jolly hero/tragic hero/romantic hero/anti-hero who ambles, trudges or swaggers through the world knowing full well that he is its centre of attention. (Presumably he never grew out of the maa ka laadla mould.) So here is Raj Kapoor’s little tramp smiling bravely through his hardships, and here is the studied tragic grandiosity of Dilip Kumar, and here is Dev Anand’s splendid conceit (visible in all the films he made from the mid-1960s on) that every woman from age 15 upwards wants only to fall into his arms. In later decades, this narcissism would be manifest in the leading man as the vigilante superhero.