Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 68

May 7, 2014

Harmonious notes – music and manliness in Alaap and Parichay

In one of those coincidences that stalk movie buffs, last week I happened to re-watch two films in which a man is discouraged from pursuing his interest in music. Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1977

Alaap

, perhaps Amitabh Bachchan’s most low-key and least-seen film in the first few years of his superstardom, has the actor playing a variant on some of his larger-than-life parts of the time. In mainstream movies like Trishul, Shakti and Deewaar, Bachchan was often in conflict with, or defined by the absence of, a father figure. He is in similar straits in Alaap, but the tone of the conflict is from the tradition of the grounded “Middle Cinema” that Mukherjee specialised in – less dramatic and fiery, more rooted in the everyday dilemmas that face a middle-class family.

As the film begins, Bachchan’s Alok Prasad has just returned to his home-town after studying classical music. “Ab toh saadhna ka lamba raasta hai, jo jeevan ki tarah saral bhi hai aur kathin bhi,” Alok’s guru has cautioned the students – meaning they aren’t “finished” with their studies, years of disciplined practice lie ahead and true commitment must span a lifetime. But this is not something Alok’s worldly father could ever understand. Barely greeting his son, he peremptorily asks what Alok plans to do with his life now, as if he had been away just for a lark. The senior Prasad (described as “Hitler”, though he is played by the Teddy-Bearish Om Prakash trying hard to look tyrannical) is contesting local elections and no doubt has firm ideas about what a worthy pursuit for a son is. Some of the early scenes make light of this situation (if I had to argue a murder case in court, I would do it in Raag Deepak, Alok quips to his bhabhi as he mulls his unsuitability to follow in his lawyer brother’s footsteps, “aur talaaq ka case Raag Jogiya mein gaoonga”), but soon there is a parting of ways, and it becomes obvious that the hero’s single-minded dedication to his art could endanger his very existence.

As the film begins, Bachchan’s Alok Prasad has just returned to his home-town after studying classical music. “Ab toh saadhna ka lamba raasta hai, jo jeevan ki tarah saral bhi hai aur kathin bhi,” Alok’s guru has cautioned the students – meaning they aren’t “finished” with their studies, years of disciplined practice lie ahead and true commitment must span a lifetime. But this is not something Alok’s worldly father could ever understand. Barely greeting his son, he peremptorily asks what Alok plans to do with his life now, as if he had been away just for a lark. The senior Prasad (described as “Hitler”, though he is played by the Teddy-Bearish Om Prakash trying hard to look tyrannical) is contesting local elections and no doubt has firm ideas about what a worthy pursuit for a son is. Some of the early scenes make light of this situation (if I had to argue a murder case in court, I would do it in Raag Deepak, Alok quips to his bhabhi as he mulls his unsuitability to follow in his lawyer brother’s footsteps, “aur talaaq ka case Raag Jogiya mein gaoonga”), but soon there is a parting of ways, and it becomes obvious that the hero’s single-minded dedication to his art could endanger his very existence.

The other film was Gulzar’s 1972 Parichay , which is sometimes described as a reworking of The Sound of Music – and indeed there are similarities in the plot of a teacher who tries to bring joy, including the love of music, into the lives of his sullen young wards. But like Alaap, the story is also about two opposing views of what a man may do with his life. In flashback, we see the music-loving Nilesh (Sanjeev Kumar) playing the sitar in his room early in the morning, going out onto the verandah to sing and to contemplate the beauty of nature, and his clashes with his authoritarian father Rai Saab (Pran), who wants his son to grow out of this dreamy-eyed artistic “phase” and do the things he is supposed to do as his only heir. To, essentially, “be a man”.

Given that ours is a cinema where music plays such a vital role – and where music composers and lyricists have mostly been male – there is something faintly ironical about narratives in which men are looked down on, or disinherited, for pursuing music as a profession. But it is easy to see why music, or art more generally, can be a threat to the status quo of a feudal or patriarchal society. The artist or artiste – with his knack for introspection ("thinking too much", as the lament goes) and his frequent inability to conform to societal expectations of people or groups – can be a problematic creature in a regimented world obsessed with class or power, and afraid of change. (Even in more benevolent contexts, there have been clashes between the pursuit of “soft” interests like art and culture, and the business of engaging with the more practical side of life; the written record of the ideological differences between Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore includes an essay where the former repeatedly referred to the latter as “the Poet”, the refrain suggesting that Gandhi was being gently sarcastic about Tagore’s rose-tinted idealism and his disconnect from the hard demands of the freedom struggle.)

In so many films made by directors like Mukherjee and Gulzar, music is a force for egalitarianism, something that helps blur boundaries. Men become more “feminine” when they sing or dance, women can become more assertive and emotionally expressive than the codes of a conservative society would normally allow them to be; gender is transcended in each direction. Music can also be equalizing in the way it erases class and caste lines. Early in Alaap, the well-off Alok bonds over a song with the cart-driver (Asrani in a super performance) who transports him home; later he finds his true home away from his father’s mansion, in the little basti where a classical singer named Sarju Bai resides. Similarly, in another Mukherjee film

Aashirwad

, the music-loving zamindar Jogi Thakur (Ashok Kumar) is never so happy as when he is practicing with his guru, a lower-class man named Baiju.

In so many films made by directors like Mukherjee and Gulzar, music is a force for egalitarianism, something that helps blur boundaries. Men become more “feminine” when they sing or dance, women can become more assertive and emotionally expressive than the codes of a conservative society would normally allow them to be; gender is transcended in each direction. Music can also be equalizing in the way it erases class and caste lines. Early in Alaap, the well-off Alok bonds over a song with the cart-driver (Asrani in a super performance) who transports him home; later he finds his true home away from his father’s mansion, in the little basti where a classical singer named Sarju Bai resides. Similarly, in another Mukherjee film

Aashirwad

, the music-loving zamindar Jogi Thakur (Ashok Kumar) is never so happy as when he is practicing with his guru, a lower-class man named Baiju.

For me you are the real Brahmin, says Jogi Thakur, because a Brahmin is one who teaches. Later, the two men sit together on the floor as they watch – and eventually participate in – a lavani dance performance; sitting with them is a Muslim friend referred to as “Mirza sahib”, and the unforced bonhomie between these three men, from very different backgrounds, is a direct result of their enthusiasm for the performing arts.** What they are doing is, within their social milieu, as subversive as Alok supporting the basti-dwellers against his own father’s land-appropriating schemes, and it shows how the performing arts can – temporarily at least – bring some harmony to an inherently unjust world.

--------------------------

** From Louise Brown's book The Dancing Girls of Lahore: Selling Love and Saving Dreams in Pakistan’s Pleasure District:

As the film begins, Bachchan’s Alok Prasad has just returned to his home-town after studying classical music. “Ab toh saadhna ka lamba raasta hai, jo jeevan ki tarah saral bhi hai aur kathin bhi,” Alok’s guru has cautioned the students – meaning they aren’t “finished” with their studies, years of disciplined practice lie ahead and true commitment must span a lifetime. But this is not something Alok’s worldly father could ever understand. Barely greeting his son, he peremptorily asks what Alok plans to do with his life now, as if he had been away just for a lark. The senior Prasad (described as “Hitler”, though he is played by the Teddy-Bearish Om Prakash trying hard to look tyrannical) is contesting local elections and no doubt has firm ideas about what a worthy pursuit for a son is. Some of the early scenes make light of this situation (if I had to argue a murder case in court, I would do it in Raag Deepak, Alok quips to his bhabhi as he mulls his unsuitability to follow in his lawyer brother’s footsteps, “aur talaaq ka case Raag Jogiya mein gaoonga”), but soon there is a parting of ways, and it becomes obvious that the hero’s single-minded dedication to his art could endanger his very existence.

As the film begins, Bachchan’s Alok Prasad has just returned to his home-town after studying classical music. “Ab toh saadhna ka lamba raasta hai, jo jeevan ki tarah saral bhi hai aur kathin bhi,” Alok’s guru has cautioned the students – meaning they aren’t “finished” with their studies, years of disciplined practice lie ahead and true commitment must span a lifetime. But this is not something Alok’s worldly father could ever understand. Barely greeting his son, he peremptorily asks what Alok plans to do with his life now, as if he had been away just for a lark. The senior Prasad (described as “Hitler”, though he is played by the Teddy-Bearish Om Prakash trying hard to look tyrannical) is contesting local elections and no doubt has firm ideas about what a worthy pursuit for a son is. Some of the early scenes make light of this situation (if I had to argue a murder case in court, I would do it in Raag Deepak, Alok quips to his bhabhi as he mulls his unsuitability to follow in his lawyer brother’s footsteps, “aur talaaq ka case Raag Jogiya mein gaoonga”), but soon there is a parting of ways, and it becomes obvious that the hero’s single-minded dedication to his art could endanger his very existence. The other film was Gulzar’s 1972 Parichay , which is sometimes described as a reworking of The Sound of Music – and indeed there are similarities in the plot of a teacher who tries to bring joy, including the love of music, into the lives of his sullen young wards. But like Alaap, the story is also about two opposing views of what a man may do with his life. In flashback, we see the music-loving Nilesh (Sanjeev Kumar) playing the sitar in his room early in the morning, going out onto the verandah to sing and to contemplate the beauty of nature, and his clashes with his authoritarian father Rai Saab (Pran), who wants his son to grow out of this dreamy-eyed artistic “phase” and do the things he is supposed to do as his only heir. To, essentially, “be a man”.

Given that ours is a cinema where music plays such a vital role – and where music composers and lyricists have mostly been male – there is something faintly ironical about narratives in which men are looked down on, or disinherited, for pursuing music as a profession. But it is easy to see why music, or art more generally, can be a threat to the status quo of a feudal or patriarchal society. The artist or artiste – with his knack for introspection ("thinking too much", as the lament goes) and his frequent inability to conform to societal expectations of people or groups – can be a problematic creature in a regimented world obsessed with class or power, and afraid of change. (Even in more benevolent contexts, there have been clashes between the pursuit of “soft” interests like art and culture, and the business of engaging with the more practical side of life; the written record of the ideological differences between Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore includes an essay where the former repeatedly referred to the latter as “the Poet”, the refrain suggesting that Gandhi was being gently sarcastic about Tagore’s rose-tinted idealism and his disconnect from the hard demands of the freedom struggle.)

In so many films made by directors like Mukherjee and Gulzar, music is a force for egalitarianism, something that helps blur boundaries. Men become more “feminine” when they sing or dance, women can become more assertive and emotionally expressive than the codes of a conservative society would normally allow them to be; gender is transcended in each direction. Music can also be equalizing in the way it erases class and caste lines. Early in Alaap, the well-off Alok bonds over a song with the cart-driver (Asrani in a super performance) who transports him home; later he finds his true home away from his father’s mansion, in the little basti where a classical singer named Sarju Bai resides. Similarly, in another Mukherjee film

Aashirwad

, the music-loving zamindar Jogi Thakur (Ashok Kumar) is never so happy as when he is practicing with his guru, a lower-class man named Baiju.

In so many films made by directors like Mukherjee and Gulzar, music is a force for egalitarianism, something that helps blur boundaries. Men become more “feminine” when they sing or dance, women can become more assertive and emotionally expressive than the codes of a conservative society would normally allow them to be; gender is transcended in each direction. Music can also be equalizing in the way it erases class and caste lines. Early in Alaap, the well-off Alok bonds over a song with the cart-driver (Asrani in a super performance) who transports him home; later he finds his true home away from his father’s mansion, in the little basti where a classical singer named Sarju Bai resides. Similarly, in another Mukherjee film

Aashirwad

, the music-loving zamindar Jogi Thakur (Ashok Kumar) is never so happy as when he is practicing with his guru, a lower-class man named Baiju. For me you are the real Brahmin, says Jogi Thakur, because a Brahmin is one who teaches. Later, the two men sit together on the floor as they watch – and eventually participate in – a lavani dance performance; sitting with them is a Muslim friend referred to as “Mirza sahib”, and the unforced bonhomie between these three men, from very different backgrounds, is a direct result of their enthusiasm for the performing arts.** What they are doing is, within their social milieu, as subversive as Alok supporting the basti-dwellers against his own father’s land-appropriating schemes, and it shows how the performing arts can – temporarily at least – bring some harmony to an inherently unjust world.

--------------------------

** From Louise Brown's book The Dancing Girls of Lahore: Selling Love and Saving Dreams in Pakistan’s Pleasure District:

Because the emotional power of music was considered raw and uncontrolled, music was deemed, like love, to have the potential to rob a man of his self-control and virtue. It was believed to possess the same subversive erotic power as the beloved. Because of its potentially destabilizing feminine power, music itself threatened the mirza’s masculinity […] for a man to dance was to indicate his receptivity to erotic attention, a passive erotic behavior that was unacceptable for a mirza.[Related thoughts in these posts: fathers and sons in the anthology film Bombay Talkies; the lavani sequence in Aashirwad. And a post about Mukherjee's lovely film Anuradha, in which the title character must sacrifice her singing career to join her doctor husband as he sets about contributing to the national cause - another pointer to sangeet as something to be reserved for the “gentler” sex, and only so long as it doesn't interfere with more "important" things ]

Published on May 07, 2014 01:01

April 24, 2014

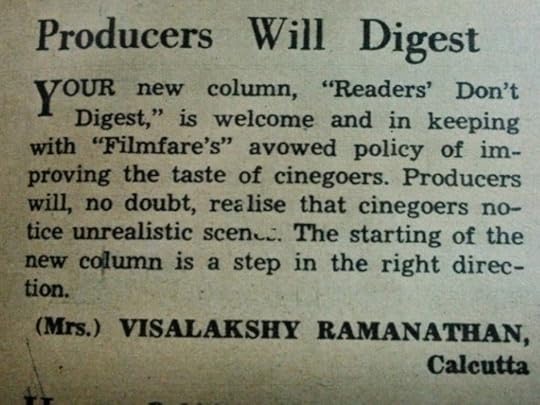

On Krishna Shastri’s Jump Cut (and notes from a humour discussion)

Here’s a paradox. A panel discussion about humour, populated by people who are funny for a living, may very possibly not be funny itself. Because it involves analysing and intellectualising something that is often analysis-resistant. Understanding the workings of comedy, and the many ways in which different people respond to it, is no easy task. No wonder Isaac Asimov once wrote a short story, “Jokester”, suggesting that humour is part of a psychological experiment being conducted on us by Godlike extraterrestrials, to study human behaviour the way we might study rats in a laboratory.

Anyway, here is the funniest thing that happened during a humour-related talk I participated in at a Chandigarh lit-fest last year: a very angry man – an acquaintance of the deceased comedian Jaspal Bhatti – bobbed up and down in his seat, banged on the chair in front of him, shook his fists at us panelists, and declaimed through a quivering moustache, “I tell you, Bhatti was NOT a comedian! He was a starrist!”

Clarity alert: he meant “satirist”. But what was really amusing was the moral indignation on display – how keen he was to defend his friend’s sullied honour, and how convinced that the very word “comedian” was a gruesome insult (though Bhatti himself, I am sure, would have had no objection to being described thus). Just a few minutes earlier, the author Krishna Shastri Devulapalli and I had been speaking about how comedy is often a thankless, underappreciated job; about literary awards rarely shortlisting funny books; about the Oscars’ reluctance to nominate comic performances even though most actors will tell you comedy is so hard to do. And now here was someone from the audience unwittingly demonstrating the point – comedy was flippant, he implied, while “satire” was respectable because it suggested social conscience and purpose.

But any sort of comedy, if well done, has a clear-sightedness that most other modes of expression don’t have. “Humour assaults us with a slice of truth,” says a character in Manu Joseph’s

The Illicit Happiness of Other People

. A case can be made that if you simply look at the world and record what you see, you automatically become a comedian. During our session, Devapulalli read out a passage from his novel

Jump Cut

in which a man named Selva – originally from a village, now living in Chennai – is required to visit a fancy store selling women’s undergarments. As Selva gapes at a pair of flimsy panties, he considers the much more durable elastic on his own underwear, “which could be cut out to make a slingshot that could kill a squirrel at twenty paces if the need arose”. A thong seems to him like a hyped version of the “komanam” worn by old men in his village. Here is an example of a funny passage that is merely showing a particular man in a situation far removed from his everyday experience. We know the kind of store this is, we can picture the “black pant-suited” salesgirl who is described as having the same glassy expression as a mannequin, and even this seemingly lowbrow situation provides food for thought: the urban reader is allowed to temporarily step outside of himself and look at things through the perplexed eyes of someone who has not grown up in a world of high-priced brands, plush malls and supercilious salespeople.

But any sort of comedy, if well done, has a clear-sightedness that most other modes of expression don’t have. “Humour assaults us with a slice of truth,” says a character in Manu Joseph’s

The Illicit Happiness of Other People

. A case can be made that if you simply look at the world and record what you see, you automatically become a comedian. During our session, Devapulalli read out a passage from his novel

Jump Cut

in which a man named Selva – originally from a village, now living in Chennai – is required to visit a fancy store selling women’s undergarments. As Selva gapes at a pair of flimsy panties, he considers the much more durable elastic on his own underwear, “which could be cut out to make a slingshot that could kill a squirrel at twenty paces if the need arose”. A thong seems to him like a hyped version of the “komanam” worn by old men in his village. Here is an example of a funny passage that is merely showing a particular man in a situation far removed from his everyday experience. We know the kind of store this is, we can picture the “black pant-suited” salesgirl who is described as having the same glassy expression as a mannequin, and even this seemingly lowbrow situation provides food for thought: the urban reader is allowed to temporarily step outside of himself and look at things through the perplexed eyes of someone who has not grown up in a world of high-priced brands, plush malls and supercilious salespeople.

Humour can be tied to nihilism – tossing a banana peel under the feet of human self-importance, mocking the idea that there is order in the world – but it can also facilitate empathy. The Illicit Happiness of Other People is about a sad man trying to understand why his 17-year-old boy killed himself, while Jump Cut is a story about another father-son relationship, as well as an ode to the “little person”, in both life and in a cut-throat movie-making industry. These synopses don’t sound funny, but both books understand that the profound and the ridiculous coexist in our lives, and they make the reader laugh while letting us stay emotionally invested in the protagonists.

Having had firsthand experience of Krishna Shastri's sense of humour in Chandigarh, I was surprised to find that Jump Cut wasn’t as full of wisecracks and clever one-liners as I had imagined it might be (not that there’s anything inherently wrong with that sort of book). What unfolds instead is something more measured, where the idea isn’t so much to be “funny” from one paragraph to the next as to provide a light, slanted take on an essentially serious premise. The book has a prologue, set in 1992 Madras, where a boy named Ray and his sister watch the preview of a film that their father has worked on. The card they have been excitedly waiting for appears on the screen. “It says ‘Story, Screenplay and Dialogue by Vasant Raj’ in big letters that fill the screen, the drum-roll underlining their importance.” That’s the father’s name on the screen, thinks the reader, but then comes the deflating coda:

Jump Cut touched a chord for me because I have been thinking about the hidden or unnoticed cogs in the filmmaking process (some recent posts: on the documentary The Human Factor, about the neglected musicians who played in orchestras for Hindi-film composers; and about the actor MacMohan, who played Sambha in Sholay), and I liked the divide the book sets up between the grand, “filmi” narrative and the mundane, unglamorous way in which things usually happen in the real world.

That said, the real world can make fiction seem feeble at times. A few months ago a writer and stand-up comedian wrote a blog post about being asked to stop a show midway because he was “mocking Indians” in front of a non-desi audience. (The provocation? Relatively innocuous, and accurate, jokes about Indian drivers honking at traffic signals.) Reading that post, I pictured all the “serious men” huffing and puffing, getting all hot under their collar and chastising the poor comedian for offending their sentiments and for being “unpatriotic”. In a world where skins keep getting thinner, being funny for a living can be tricky. But the ability to laugh at yourself and at your holiest cows is one of the essential steps on the road to growing up, and this is a lesson well learnt in the company of skilled comedy writers – so what if they don’t win all those big literary awards.

[Here is a related post about "tasteless humour", with an anecdote I had thought of using at the Chandigarh lit-fest - the Punjabi audience may have appreciated it - before chickening out]

Anyway, here is the funniest thing that happened during a humour-related talk I participated in at a Chandigarh lit-fest last year: a very angry man – an acquaintance of the deceased comedian Jaspal Bhatti – bobbed up and down in his seat, banged on the chair in front of him, shook his fists at us panelists, and declaimed through a quivering moustache, “I tell you, Bhatti was NOT a comedian! He was a starrist!”

Clarity alert: he meant “satirist”. But what was really amusing was the moral indignation on display – how keen he was to defend his friend’s sullied honour, and how convinced that the very word “comedian” was a gruesome insult (though Bhatti himself, I am sure, would have had no objection to being described thus). Just a few minutes earlier, the author Krishna Shastri Devulapalli and I had been speaking about how comedy is often a thankless, underappreciated job; about literary awards rarely shortlisting funny books; about the Oscars’ reluctance to nominate comic performances even though most actors will tell you comedy is so hard to do. And now here was someone from the audience unwittingly demonstrating the point – comedy was flippant, he implied, while “satire” was respectable because it suggested social conscience and purpose.

But any sort of comedy, if well done, has a clear-sightedness that most other modes of expression don’t have. “Humour assaults us with a slice of truth,” says a character in Manu Joseph’s

The Illicit Happiness of Other People

. A case can be made that if you simply look at the world and record what you see, you automatically become a comedian. During our session, Devapulalli read out a passage from his novel

Jump Cut

in which a man named Selva – originally from a village, now living in Chennai – is required to visit a fancy store selling women’s undergarments. As Selva gapes at a pair of flimsy panties, he considers the much more durable elastic on his own underwear, “which could be cut out to make a slingshot that could kill a squirrel at twenty paces if the need arose”. A thong seems to him like a hyped version of the “komanam” worn by old men in his village. Here is an example of a funny passage that is merely showing a particular man in a situation far removed from his everyday experience. We know the kind of store this is, we can picture the “black pant-suited” salesgirl who is described as having the same glassy expression as a mannequin, and even this seemingly lowbrow situation provides food for thought: the urban reader is allowed to temporarily step outside of himself and look at things through the perplexed eyes of someone who has not grown up in a world of high-priced brands, plush malls and supercilious salespeople.

But any sort of comedy, if well done, has a clear-sightedness that most other modes of expression don’t have. “Humour assaults us with a slice of truth,” says a character in Manu Joseph’s

The Illicit Happiness of Other People

. A case can be made that if you simply look at the world and record what you see, you automatically become a comedian. During our session, Devapulalli read out a passage from his novel

Jump Cut

in which a man named Selva – originally from a village, now living in Chennai – is required to visit a fancy store selling women’s undergarments. As Selva gapes at a pair of flimsy panties, he considers the much more durable elastic on his own underwear, “which could be cut out to make a slingshot that could kill a squirrel at twenty paces if the need arose”. A thong seems to him like a hyped version of the “komanam” worn by old men in his village. Here is an example of a funny passage that is merely showing a particular man in a situation far removed from his everyday experience. We know the kind of store this is, we can picture the “black pant-suited” salesgirl who is described as having the same glassy expression as a mannequin, and even this seemingly lowbrow situation provides food for thought: the urban reader is allowed to temporarily step outside of himself and look at things through the perplexed eyes of someone who has not grown up in a world of high-priced brands, plush malls and supercilious salespeople.Humour can be tied to nihilism – tossing a banana peel under the feet of human self-importance, mocking the idea that there is order in the world – but it can also facilitate empathy. The Illicit Happiness of Other People is about a sad man trying to understand why his 17-year-old boy killed himself, while Jump Cut is a story about another father-son relationship, as well as an ode to the “little person”, in both life and in a cut-throat movie-making industry. These synopses don’t sound funny, but both books understand that the profound and the ridiculous coexist in our lives, and they make the reader laugh while letting us stay emotionally invested in the protagonists.

Having had firsthand experience of Krishna Shastri's sense of humour in Chandigarh, I was surprised to find that Jump Cut wasn’t as full of wisecracks and clever one-liners as I had imagined it might be (not that there’s anything inherently wrong with that sort of book). What unfolds instead is something more measured, where the idea isn’t so much to be “funny” from one paragraph to the next as to provide a light, slanted take on an essentially serious premise. The book has a prologue, set in 1992 Madras, where a boy named Ray and his sister watch the preview of a film that their father has worked on. The card they have been excitedly waiting for appears on the screen. “It says ‘Story, Screenplay and Dialogue by Vasant Raj’ in big letters that fill the screen, the drum-roll underlining their importance.” That’s the father’s name on the screen, thinks the reader, but then comes the deflating coda:

At the bottom of the screen, in barely readable letters, is the legend:

Associate: RamanAs this opening should make clear, there will be a tinge of melancholia throughout this story, even if it is largely hidden beneath the warm, good-natured tone of the writing. We never really get to “meet” the anonymous Raman in the narrative’s present tense, but the early chapters in which the adult Ray uncovers things about his deceased father are interspersed with short diary entries written by the dead man over the years: entries that reveal something of the inner world of a man who must have been taciturn and unobtrusive – a father who notices that his teenage son has a crush on a girl and also knows that he must never let on that he has noticed; a widower who drily notes that “the editor of real life can be quite abrupt” as he recalls how suddenly and randomly his wife was taken from him.

Then it is gone.

Jump Cut touched a chord for me because I have been thinking about the hidden or unnoticed cogs in the filmmaking process (some recent posts: on the documentary The Human Factor, about the neglected musicians who played in orchestras for Hindi-film composers; and about the actor MacMohan, who played Sambha in Sholay), and I liked the divide the book sets up between the grand, “filmi” narrative and the mundane, unglamorous way in which things usually happen in the real world.

That said, the real world can make fiction seem feeble at times. A few months ago a writer and stand-up comedian wrote a blog post about being asked to stop a show midway because he was “mocking Indians” in front of a non-desi audience. (The provocation? Relatively innocuous, and accurate, jokes about Indian drivers honking at traffic signals.) Reading that post, I pictured all the “serious men” huffing and puffing, getting all hot under their collar and chastising the poor comedian for offending their sentiments and for being “unpatriotic”. In a world where skins keep getting thinner, being funny for a living can be tricky. But the ability to laugh at yourself and at your holiest cows is one of the essential steps on the road to growing up, and this is a lesson well learnt in the company of skilled comedy writers – so what if they don’t win all those big literary awards.

[Here is a related post about "tasteless humour", with an anecdote I had thought of using at the Chandigarh lit-fest - the Punjabi audience may have appreciated it - before chickening out]

Published on April 24, 2014 23:39

April 22, 2014

How I met Norman’s mother (a spot of movie tourism)

[Did this for Business Standard]

I’m not usually enthusiastic about having a camera aimed at me (though I’m not fascist about it either, like the people who believe the thing is a devil’s tool meant to suck their souls out through their eyeballs or something). Even when travelling in scenic places, I’d rather someone just took a candid shot instead of expecting me to stand in front of something and grin moronically at a lens.

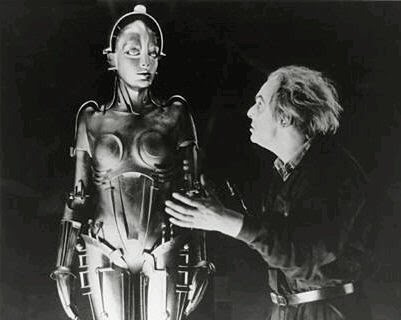

Which in no way explains why, if you chanced to visit the Cinémathèque Française museum on a particular Friday afternoon last month, you would have found me squatting next to Mrs Bates’s skull and grinning moronically at a lens. And then doing it again, to get another angle; and then yet again, after checking the light settings and tut-tutting; all the while keeping an eye out for the museum police who frowned at photography in the premises. Nor does it explain why I then stood next to Maria the robot and made faux-dramatic poses in an attempt to replicate a famous scene from a 1926 film.

But these were special circumstances: Mrs Bates and Maria are important figures in my movie-watching career. The former is the shadowy protagonist of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which infected my life when I was 13, getting me thinking about films as art and sending me down a rabbit-hole of analytical literature about movies. The latter is one of the frosty legends of early film history, the automaton created by an evil scientist in Fritz Lang’s great silent film Metropolis. And so, having arrived in the city where people typically make a beeline for Notre Dame and Versailles, for Angelina’s hot chocolate and Berthillon’s ice creams, I prioritised a meeting with these two enigmatic ladies of the night. As Mrs Bates’s little boy Norman put it, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?”

Mother Bates makes her famous appearance in the climax of Psycho, in a creaky (by today’s standards) but unsettling scene in the basement, where we discover that Norman’s mummy is not a living, domineering harridan but a long-dead, carefully preserved corpse. If I had wanted my illusions to be just as well-preserved, I would have avoided going to the museum at all, so that my only mental picture of her would be as she appears in the film. There was something both comical and poignant about seeing her in a glass cage at the Cinémathèque. Bathed in a beam of yellow light, she stood out from a distance in the darkened room; the idea was presumably to make her look spooky, but it also drew attention to her as an exhibit, something that visitors could point and chortle at (or sit down next to and smile stupidly for a camera). Besides, she was unexpectedly small. (What was I expecting? A two-foot-tall skull with shark-like teeth?)

Mother Bates makes her famous appearance in the climax of Psycho, in a creaky (by today’s standards) but unsettling scene in the basement, where we discover that Norman’s mummy is not a living, domineering harridan but a long-dead, carefully preserved corpse. If I had wanted my illusions to be just as well-preserved, I would have avoided going to the museum at all, so that my only mental picture of her would be as she appears in the film. There was something both comical and poignant about seeing her in a glass cage at the Cinémathèque. Bathed in a beam of yellow light, she stood out from a distance in the darkened room; the idea was presumably to make her look spooky, but it also drew attention to her as an exhibit, something that visitors could point and chortle at (or sit down next to and smile stupidly for a camera). Besides, she was unexpectedly small. (What was I expecting? A two-foot-tall skull with shark-like teeth?)

Looking at other artefacts – the starfish in the jar from Man Ray’s 1928 film

The Sea Star

, costumes from such movies as Jean Cocteau’s 1946 Beauty and the Beast – was a strange experience too. Props and objects that have such immediate, vivid associations for a viewer can, when removed from their familiar contexts, become banal and smaller than life. Cocteau’s film was in gorgeous black and white, but these costumes were in “real-world” colour and they seemed garish, almost vulgar when set against the images from the film, playing on a screen above. There was a series of still photos from the Beauty and the Beast set, which showed the

Looking at other artefacts – the starfish in the jar from Man Ray’s 1928 film

The Sea Star

, costumes from such movies as Jean Cocteau’s 1946 Beauty and the Beast – was a strange experience too. Props and objects that have such immediate, vivid associations for a viewer can, when removed from their familiar contexts, become banal and smaller than life. Cocteau’s film was in gorgeous black and white, but these costumes were in “real-world” colour and they seemed garish, almost vulgar when set against the images from the film, playing on a screen above. There was a series of still photos from the Beauty and the Beast set, which showed the

blandly handsome actor Jean Marais applying the layers of makeup that would transform him into the imperious, tragic Beast. For anyone who has been immersed in the otherworldly milieu of Cocteau’s film, these stills are an exercise in demystification; with a movie like that, which gives the impression of having sprung fully formed from an alternate universe, you don’t want to be reminded that it was put together by a cast and crew, who were probably doing mundane things like talking about the day’s news or taking cigarette breaks in between shots.

blandly handsome actor Jean Marais applying the layers of makeup that would transform him into the imperious, tragic Beast. For anyone who has been immersed in the otherworldly milieu of Cocteau’s film, these stills are an exercise in demystification; with a movie like that, which gives the impression of having sprung fully formed from an alternate universe, you don’t want to be reminded that it was put together by a cast and crew, who were probably doing mundane things like talking about the day’s news or taking cigarette breaks in between shots.

Yet such experiences can also bring a new, more measured respect for the creative process – the processes by which everyday things are transmuted into magic and art, with long-term effects on people’s lives and personalities. (I would almost certainly not have become a professional writer if I hadn’t watched Psycho when I did.) Returning to Ma Bates: here is a wrinkled little skull replica, not particularly authentic-looking or scary when you see it in the cold light of day. Yet someone designed it keeping in mind a film’s lighting and colour scheme, and the desired Grand Guignol-like effect of the climactic revelation. They arranged it just so, placing it in a chair that would swivel around dramatically; at the crucial moment a swinging lightbulb cast shadows over it, making the eye sockets seem alive and menacing; and Bernard Herrman’s music score with its screaming violins added to the effect of the scene.

Yet such experiences can also bring a new, more measured respect for the creative process – the processes by which everyday things are transmuted into magic and art, with long-term effects on people’s lives and personalities. (I would almost certainly not have become a professional writer if I hadn’t watched Psycho when I did.) Returning to Ma Bates: here is a wrinkled little skull replica, not particularly authentic-looking or scary when you see it in the cold light of day. Yet someone designed it keeping in mind a film’s lighting and colour scheme, and the desired Grand Guignol-like effect of the climactic revelation. They arranged it just so, placing it in a chair that would swivel around dramatically; at the crucial moment a swinging lightbulb cast shadows over it, making the eye sockets seem alive and menacing; and Bernard Herrman’s music score with its screaming violins added to the effect of the scene.

And now here she was more than 50 years later, outside of the film, in a boringly polychrome world, staring blankly at me from her glass home. It was a little deflating, but the sense of mystery wasn’t completely gone. For a moment I fancied I could hear Norman’s voice saying "I think we're all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out” followed by Mother’s cackle: “They know I can't move a finger, and I won't. I'll just sit here and be quiet, just in case they do... suspect me."

[The earlier post with the museum photos is here. And here is "Monsters I have known", my piece about horror-movie love for The Popcorn Essayists]

I’m not usually enthusiastic about having a camera aimed at me (though I’m not fascist about it either, like the people who believe the thing is a devil’s tool meant to suck their souls out through their eyeballs or something). Even when travelling in scenic places, I’d rather someone just took a candid shot instead of expecting me to stand in front of something and grin moronically at a lens.

Which in no way explains why, if you chanced to visit the Cinémathèque Française museum on a particular Friday afternoon last month, you would have found me squatting next to Mrs Bates’s skull and grinning moronically at a lens. And then doing it again, to get another angle; and then yet again, after checking the light settings and tut-tutting; all the while keeping an eye out for the museum police who frowned at photography in the premises. Nor does it explain why I then stood next to Maria the robot and made faux-dramatic poses in an attempt to replicate a famous scene from a 1926 film.

But these were special circumstances: Mrs Bates and Maria are important figures in my movie-watching career. The former is the shadowy protagonist of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which infected my life when I was 13, getting me thinking about films as art and sending me down a rabbit-hole of analytical literature about movies. The latter is one of the frosty legends of early film history, the automaton created by an evil scientist in Fritz Lang’s great silent film Metropolis. And so, having arrived in the city where people typically make a beeline for Notre Dame and Versailles, for Angelina’s hot chocolate and Berthillon’s ice creams, I prioritised a meeting with these two enigmatic ladies of the night. As Mrs Bates’s little boy Norman put it, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?”

Mother Bates makes her famous appearance in the climax of Psycho, in a creaky (by today’s standards) but unsettling scene in the basement, where we discover that Norman’s mummy is not a living, domineering harridan but a long-dead, carefully preserved corpse. If I had wanted my illusions to be just as well-preserved, I would have avoided going to the museum at all, so that my only mental picture of her would be as she appears in the film. There was something both comical and poignant about seeing her in a glass cage at the Cinémathèque. Bathed in a beam of yellow light, she stood out from a distance in the darkened room; the idea was presumably to make her look spooky, but it also drew attention to her as an exhibit, something that visitors could point and chortle at (or sit down next to and smile stupidly for a camera). Besides, she was unexpectedly small. (What was I expecting? A two-foot-tall skull with shark-like teeth?)

Mother Bates makes her famous appearance in the climax of Psycho, in a creaky (by today’s standards) but unsettling scene in the basement, where we discover that Norman’s mummy is not a living, domineering harridan but a long-dead, carefully preserved corpse. If I had wanted my illusions to be just as well-preserved, I would have avoided going to the museum at all, so that my only mental picture of her would be as she appears in the film. There was something both comical and poignant about seeing her in a glass cage at the Cinémathèque. Bathed in a beam of yellow light, she stood out from a distance in the darkened room; the idea was presumably to make her look spooky, but it also drew attention to her as an exhibit, something that visitors could point and chortle at (or sit down next to and smile stupidly for a camera). Besides, she was unexpectedly small. (What was I expecting? A two-foot-tall skull with shark-like teeth?) Looking at other artefacts – the starfish in the jar from Man Ray’s 1928 film

The Sea Star

, costumes from such movies as Jean Cocteau’s 1946 Beauty and the Beast – was a strange experience too. Props and objects that have such immediate, vivid associations for a viewer can, when removed from their familiar contexts, become banal and smaller than life. Cocteau’s film was in gorgeous black and white, but these costumes were in “real-world” colour and they seemed garish, almost vulgar when set against the images from the film, playing on a screen above. There was a series of still photos from the Beauty and the Beast set, which showed the

Looking at other artefacts – the starfish in the jar from Man Ray’s 1928 film

The Sea Star

, costumes from such movies as Jean Cocteau’s 1946 Beauty and the Beast – was a strange experience too. Props and objects that have such immediate, vivid associations for a viewer can, when removed from their familiar contexts, become banal and smaller than life. Cocteau’s film was in gorgeous black and white, but these costumes were in “real-world” colour and they seemed garish, almost vulgar when set against the images from the film, playing on a screen above. There was a series of still photos from the Beauty and the Beast set, which showed the

blandly handsome actor Jean Marais applying the layers of makeup that would transform him into the imperious, tragic Beast. For anyone who has been immersed in the otherworldly milieu of Cocteau’s film, these stills are an exercise in demystification; with a movie like that, which gives the impression of having sprung fully formed from an alternate universe, you don’t want to be reminded that it was put together by a cast and crew, who were probably doing mundane things like talking about the day’s news or taking cigarette breaks in between shots.

blandly handsome actor Jean Marais applying the layers of makeup that would transform him into the imperious, tragic Beast. For anyone who has been immersed in the otherworldly milieu of Cocteau’s film, these stills are an exercise in demystification; with a movie like that, which gives the impression of having sprung fully formed from an alternate universe, you don’t want to be reminded that it was put together by a cast and crew, who were probably doing mundane things like talking about the day’s news or taking cigarette breaks in between shots. Yet such experiences can also bring a new, more measured respect for the creative process – the processes by which everyday things are transmuted into magic and art, with long-term effects on people’s lives and personalities. (I would almost certainly not have become a professional writer if I hadn’t watched Psycho when I did.) Returning to Ma Bates: here is a wrinkled little skull replica, not particularly authentic-looking or scary when you see it in the cold light of day. Yet someone designed it keeping in mind a film’s lighting and colour scheme, and the desired Grand Guignol-like effect of the climactic revelation. They arranged it just so, placing it in a chair that would swivel around dramatically; at the crucial moment a swinging lightbulb cast shadows over it, making the eye sockets seem alive and menacing; and Bernard Herrman’s music score with its screaming violins added to the effect of the scene.

Yet such experiences can also bring a new, more measured respect for the creative process – the processes by which everyday things are transmuted into magic and art, with long-term effects on people’s lives and personalities. (I would almost certainly not have become a professional writer if I hadn’t watched Psycho when I did.) Returning to Ma Bates: here is a wrinkled little skull replica, not particularly authentic-looking or scary when you see it in the cold light of day. Yet someone designed it keeping in mind a film’s lighting and colour scheme, and the desired Grand Guignol-like effect of the climactic revelation. They arranged it just so, placing it in a chair that would swivel around dramatically; at the crucial moment a swinging lightbulb cast shadows over it, making the eye sockets seem alive and menacing; and Bernard Herrman’s music score with its screaming violins added to the effect of the scene. And now here she was more than 50 years later, outside of the film, in a boringly polychrome world, staring blankly at me from her glass home. It was a little deflating, but the sense of mystery wasn’t completely gone. For a moment I fancied I could hear Norman’s voice saying "I think we're all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out” followed by Mother’s cackle: “They know I can't move a finger, and I won't. I'll just sit here and be quiet, just in case they do... suspect me."

[The earlier post with the museum photos is here. And here is "Monsters I have known", my piece about horror-movie love for The Popcorn Essayists]

Published on April 22, 2014 04:46

April 12, 2014

Revisiting J P Dutta’s Hathyar (and reflections on the bad old 1980s)

[Did a shorter version of this essay for the new issue of The Indian Quarterly]

Those of us whose cinematic consciousness was shaped in the 1980s tend to agree that, nostalgia aside, these were poor times for mainstream Hindi cinema. Actors did multiple shifts a day, zombie-walking through barely scripted potboilers (with the end results rarely indicating that they had succeeded in telling one character from the next, or that the films had expected them to). Production design was non-existent, comedy tracks appalling, and there were those ghastly closing shots where an assembly of surviving good guys stood together in a huddle beaming at the camera in the “mahurat” pose (after a few seconds of dutiful glycerine-shedding because one of their number had just sacrificed his life to save the day). Residue from the Angry Young Man films of the 1970s included the very worst of Amitabh Bachchan (from Pukar and Mahaan through Toofan and Jaadugar). In the immediate pre-liberalisation, pre-multiplex era, “Bollywood” operated in its own vacuum.

Today the DVD culture and the work done by NFDC has made it possible to see good, restored prints of the “parallel” cinema of the time, the best work of Benegal, Nihalani, Mishra and others. And so, for those of us of a certain age who like to think we take cinema seriously, it seems natural to focus our energies on revisiting those movies (which we were too young to appreciate when they came out) rather than waste time and effort trying to locate the few scattered gems that may have come out of the mainstream.

As I have written before on this blog, the first two years of the 1990s were when I became distanced from Hindi films (though a part of me loved the dhishum-dhishum and the familiar, reassuring structures) and sought nourishment elsewhere. I hadn’t read much film theory, had no concept yet of auteurs – like most young viewers, I mostly didn’t even think of films in terms of their directors. Yet, even at age 13, turning nastik and renouncing the mandir of Hindi movies, I knew that some of these films had a special energy in them and gave the impression that actual thought was taking place at the level of camerawork, scripting or performance; that an individual sensibility lay behind the whole. Mukul Anand was one such director (while

Hum

was the only film of his I whole-heartedly liked, there were stand-up-and-take-notice moments in nearly all his work, even in this tiresome thing called

Khoon ka Karz

). Another such director was J P Dutta, and one of my clearest memories from the summer of 1989 was watching Dutta’s

Hathyar

and sensing, without being able to articulate it, that I was seeing something more interesting than the regular action multi-starrer. Looking at tacky posters of Hathyar, with red-eyed Dharmendra and droopy-eyed Sanjay Dutt flaring nostrils and brandishing guns, you wouldn’t think it was any different from a dozen other khoon-aur-badlaa films that these actors were doing around the same time, but that would be an injustice to this layered work about the seductiveness of violence.

As I have written before on this blog, the first two years of the 1990s were when I became distanced from Hindi films (though a part of me loved the dhishum-dhishum and the familiar, reassuring structures) and sought nourishment elsewhere. I hadn’t read much film theory, had no concept yet of auteurs – like most young viewers, I mostly didn’t even think of films in terms of their directors. Yet, even at age 13, turning nastik and renouncing the mandir of Hindi movies, I knew that some of these films had a special energy in them and gave the impression that actual thought was taking place at the level of camerawork, scripting or performance; that an individual sensibility lay behind the whole. Mukul Anand was one such director (while

Hum

was the only film of his I whole-heartedly liked, there were stand-up-and-take-notice moments in nearly all his work, even in this tiresome thing called

Khoon ka Karz

). Another such director was J P Dutta, and one of my clearest memories from the summer of 1989 was watching Dutta’s

Hathyar

and sensing, without being able to articulate it, that I was seeing something more interesting than the regular action multi-starrer. Looking at tacky posters of Hathyar, with red-eyed Dharmendra and droopy-eyed Sanjay Dutt flaring nostrils and brandishing guns, you wouldn’t think it was any different from a dozen other khoon-aur-badlaa films that these actors were doing around the same time, but that would be an injustice to this layered work about the seductiveness of violence.

This month marks 25 years since the film’s commercial release. Though it has a tiny cult following among knowledgeable buffs, it deserves to be better known; along with the director’s earlier Ghulami , it is the high point of an erratic but important career. Dutta’s work has always been prone to flab and overstatement – something that is most obvious in the star-studded Kshatriya and LOC Kargil – but these 1980s films nicely balanced the large canvas with the intimate moment. They used sprawling vistas in ways that did justice to the conceit of the 70 mm screen, while inhabiting these vistas with well-defined characters who had interiority. Looked at from a distance, they can seem like standard uber-macho sagas, but on closer examination they turn out to be thoughtful critiques of violence and how that violence is related to a feudal, patriarchal tradition and passed down until it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. There are strong roles for women as tempering influences or – in some cases – as facilitators for the more unsavoury aspects of tradition. And even while operating within the hyper-dramatic idiom of the commercial Hindi film, they successfully incorporated elements from outside that world. Ghulami has Mithun Chakraborty as a wisecracking action hero (whose trademark line “koi shaq?” was guaranteed to draw front-bench whistles) but also has a side-track featuring parallel-cinema stars Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah as husband and wife who weigh mutual respect against ideological differences. And in Hathyar, the voice of conscience is played by someone who usually worked in a very different corner of the mainstream – Rishi Kapoor, whose presence here, in one of his best roles of the time, is a tip-off that this won’t be your regular action film.**

world. Ghulami has Mithun Chakraborty as a wisecracking action hero (whose trademark line “koi shaq?” was guaranteed to draw front-bench whistles) but also has a side-track featuring parallel-cinema stars Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah as husband and wife who weigh mutual respect against ideological differences. And in Hathyar, the voice of conscience is played by someone who usually worked in a very different corner of the mainstream – Rishi Kapoor, whose presence here, in one of his best roles of the time, is a tip-off that this won’t be your regular action film.**

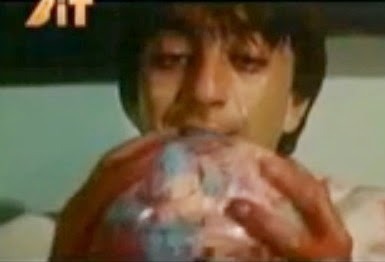

Memory can play tricks on us when it comes to old movies, but the lullaby that bookends Hathyar’s narrative turned out to be exactly as I remembered it when I saw the film again recently. In the opening shot a little boy, initially seen in silhouette, sits on a rocking horse as his thakur father sings to him about a prince who roams the world on a flying steed and returns home when he is tired. (“Ek raja ke bête ko lekar / Udne waala ghoda…”) They are interrupted by an uncle – a more militant member of the thakur’s clan – who gives the child a toy gun, against the father’s protests. Our Avinash won’t grow up to be a coward, the chacha says pointedly. “Aaj kal sharaafat ko hee kaayarta kehte hain,” (“These days decency is mistaken for cowardice”) the father sighs, trying to take the gun away from his boy, but the child is already enthralled, he won’t let go – “Nahin, hum kheleinge” are his chilling words – and the framing of the shot (which dissolves into the adult Avinash’s arms holding a real rifle) makes it seem like the weapon is an extension of his hand. The circle begun by these scenes will be completed in the film's final sequence, set in a toy shop where Avinash realises that running his blood-smeared palms over a plastic globe is the closest he will come to having the world in his hands or flying to exotic lands on a magic horse.

In the casting of Sanjay Dutt as a gun-obsessed young man who becomes a pawn in games played by larger forces, Hathyar weirdly pre-echoes real-world events. In cinematic terms though, it is a forerunner to Ram Gopal Varma’s

Satya

and other sleek, realistic city-crime films that would herald the multiplex era. Dutta’s early work was mostly set in villages and expanses of sunbaked desert where feudalism ran rampant and the line between rebel and daku, victim and aggressor, was erased. (Anyone who had the pleasure of watching Ghulami on a big screen – I have a dim childhood memory of this, though I may have nodded off during the Naseer-Smita scenes – will know how sweeping his visual sense was and how well he used these majestic settings.) But Hathyar was, literally, different terrain for him. Arriving in Bombay to escape village feuds, Avinash’s father is immediately confronted by violence and apathy of a different sort, though the hoodlums here are dressed in jeans and sneakers. “You said we’d move to the city to get away from the jungles, to live with civilised people,” Avinash’s mother (Asha Parekh in a good latter-day role) sarcastically tells her husband, “Well, here we are. Go and hug the cultured people you were so eager to meet.”

In the casting of Sanjay Dutt as a gun-obsessed young man who becomes a pawn in games played by larger forces, Hathyar weirdly pre-echoes real-world events. In cinematic terms though, it is a forerunner to Ram Gopal Varma’s

Satya

and other sleek, realistic city-crime films that would herald the multiplex era. Dutta’s early work was mostly set in villages and expanses of sunbaked desert where feudalism ran rampant and the line between rebel and daku, victim and aggressor, was erased. (Anyone who had the pleasure of watching Ghulami on a big screen – I have a dim childhood memory of this, though I may have nodded off during the Naseer-Smita scenes – will know how sweeping his visual sense was and how well he used these majestic settings.) But Hathyar was, literally, different terrain for him. Arriving in Bombay to escape village feuds, Avinash’s father is immediately confronted by violence and apathy of a different sort, though the hoodlums here are dressed in jeans and sneakers. “You said we’d move to the city to get away from the jungles, to live with civilised people,” Avinash’s mother (Asha Parekh in a good latter-day role) sarcastically tells her husband, “Well, here we are. Go and hug the cultured people you were so eager to meet.”

The ugly face of the metropolis is omnipresent – they see someone who has fallen off a train and died, and people being casual and indifferent about the tragedy – but new friendships and ties are formed too, and the city's “good” side seems to converge in the personality of one man, their principled and sensitive neighbour Sami bhai (Kapoor). Meanwhile, Avinash gets seduced by the Bombay underworld. This is partly circumstantial, but it could be a natural arc of his personality and upbringing: when we first saw him as an adult, back in the village, he was more interested in the deer at the end of his rifle than in his girlfriend Suman’s talk of romance and marriage; he dashed off while she was mid-sentence, in a scene that played like a variant on a famous episode from the Ramayana (and in this age of epic retellings and reexaminations, it might briefly make you wonder: was Rama’s pursuit of the deer Maricha driven as much by primal blood-lust as by the desire to fulfill his wife’s wish?).

In fact, one possible weakness of Hathyar is that it sometimes appears to blur two separate issues. The first involves the choices that face an unprivileged boy struggling to make ends meet and to support his mother in a predatory world. The second is his own apparent love of violence for its own sake, and the hint that he can prioritise it above his close relationships. At times the film seems undecided about whether to treat Avinash as an amoral sociopath with aggression running in his veins or as a pawn of fate, a cinematic descendant of Deewaar’s angry young man Vijay. But perhaps the two things aren’t mutually exclusive - perhaps what is being suggested is that if Avinash’s background and upbringing hadn’t been so rooted in casual bloodshed, it might have been easier for him to make the “right” choices later in life.

In fact, one possible weakness of Hathyar is that it sometimes appears to blur two separate issues. The first involves the choices that face an unprivileged boy struggling to make ends meet and to support his mother in a predatory world. The second is his own apparent love of violence for its own sake, and the hint that he can prioritise it above his close relationships. At times the film seems undecided about whether to treat Avinash as an amoral sociopath with aggression running in his veins or as a pawn of fate, a cinematic descendant of Deewaar’s angry young man Vijay. But perhaps the two things aren’t mutually exclusive - perhaps what is being suggested is that if Avinash’s background and upbringing hadn’t been so rooted in casual bloodshed, it might have been easier for him to make the “right” choices later in life.

Hathyar doesn’t have the cool, organic sophistication of the gangster films that would come a few years later, such as RGV’s work, but there is an emotional directness in its key moments, and some very striking images, such as a shot of two people huddled together between trains passing on adjacent tracks shortly after the discovery of a dead body. Effective use is made of a minatory background score, and the scene that introduces the adult Avinash has the deliberate texture of gun porn, with loving close-ups of a shiny rifle being assembled, a hand stroking it, loading bullets, cocking it, taking aim. And watching such scenes, an old question in popular-film studies rears its head: is it possible for a powerful visual medium like cinema to meaningfully critique something even as it depicts it? If a film sets out to be a thoughtful commentary on violence but also contains well-executed action sequences – or soulful music to underline the protagonist’s personal dilemmas – does it compromise itself by making the violence “thrilling”?

Hathyar doesn’t have the cool, organic sophistication of the gangster films that would come a few years later, such as RGV’s work, but there is an emotional directness in its key moments, and some very striking images, such as a shot of two people huddled together between trains passing on adjacent tracks shortly after the discovery of a dead body. Effective use is made of a minatory background score, and the scene that introduces the adult Avinash has the deliberate texture of gun porn, with loving close-ups of a shiny rifle being assembled, a hand stroking it, loading bullets, cocking it, taking aim. And watching such scenes, an old question in popular-film studies rears its head: is it possible for a powerful visual medium like cinema to meaningfully critique something even as it depicts it? If a film sets out to be a thoughtful commentary on violence but also contains well-executed action sequences – or soulful music to underline the protagonist’s personal dilemmas – does it compromise itself by making the violence “thrilling”?

There are no easy answers to these questions. Personally I don’t believe an objective distinction can always be made between films that are gratuitous/exploitative and films that are well-intentioned: directors and writers bring diverse sensibilities and approaches to the same material, and much depends on interpretation as well as on a viewer’s ability to distinguish between something that might temporarily be stimulating when viewed on a screen while being abhorrent or condemnable in the real world. But this aside, anyone watching Hathyar should be able to see that it accommodates a wide range of attitudes to violence and pacifism, cynicism and idealism.

Dutta’s best work (I’m thinking mainly of Ghulami and Hathyar – and perhaps Yateem, which I don’t remember all that well) sometimes reminds me of the cinema of Otto Preminger, in that it deals with intimate human stories within very large, multi-character frames (so large, in fact, that the films are constantly in danger of being dismissed as bloated epics by a viewer who hasn’t attentively watched them). Like Preminger’s Advise and Consent (a remarkably mature, multi-dimensional political film), Exodus and Anatomy of a Murder, these films present diverse points of view and life experiences without passing sweeping judgements – and yet without getting so fatalistic that they completely abjure notions of right and wrong.

In Hathyar, a poetic contrast is made between Avinash’s father putting his life into his toy statues, making something new and creative out of mud, and his son who kills people and watches their bodies fall in the mud. But lines are not clearly defined. There is the implication that the Gandhi-like men of integrity in this cut-throat world can “live by their principles” partly because someone less idealistic, more open to compromise, is looking out for them. And yet the film does this without glamorising those who chose the path of crime. All this adds up to a level of complexity that would point the way ahead to the more thoughtful, grounded screenwriting of the indie film culture.

In Hathyar, a poetic contrast is made between Avinash’s father putting his life into his toy statues, making something new and creative out of mud, and his son who kills people and watches their bodies fall in the mud. But lines are not clearly defined. There is the implication that the Gandhi-like men of integrity in this cut-throat world can “live by their principles” partly because someone less idealistic, more open to compromise, is looking out for them. And yet the film does this without glamorising those who chose the path of crime. All this adds up to a level of complexity that would point the way ahead to the more thoughtful, grounded screenwriting of the indie film culture.

-------------------------

** One of Kapoor’s finest moments in the film – a triad of wordless gestures that take up just a few seconds – is a late scene where his character Sami bhai is beaten up by Avinash. Having offered no resistance, the dazed Sami bhai is now clutching a pole, out of breath. When he sees that Avinash is done and is about to walk away, he first holds his hands out in a “what, you’re finished?” gesture, then indicates “come, hit me some more, I’m still standing” and finally, as Avinash makes no move back, Sami – though still visibly shaken and reeling in a way that not many beaten-up leading men of the time seemed to be – waves his hands in an almost dismissive gesture, as if to say "This was the extent of your bravado? You have a lot to learn about real courage."

Those of us whose cinematic consciousness was shaped in the 1980s tend to agree that, nostalgia aside, these were poor times for mainstream Hindi cinema. Actors did multiple shifts a day, zombie-walking through barely scripted potboilers (with the end results rarely indicating that they had succeeded in telling one character from the next, or that the films had expected them to). Production design was non-existent, comedy tracks appalling, and there were those ghastly closing shots where an assembly of surviving good guys stood together in a huddle beaming at the camera in the “mahurat” pose (after a few seconds of dutiful glycerine-shedding because one of their number had just sacrificed his life to save the day). Residue from the Angry Young Man films of the 1970s included the very worst of Amitabh Bachchan (from Pukar and Mahaan through Toofan and Jaadugar). In the immediate pre-liberalisation, pre-multiplex era, “Bollywood” operated in its own vacuum.

Today the DVD culture and the work done by NFDC has made it possible to see good, restored prints of the “parallel” cinema of the time, the best work of Benegal, Nihalani, Mishra and others. And so, for those of us of a certain age who like to think we take cinema seriously, it seems natural to focus our energies on revisiting those movies (which we were too young to appreciate when they came out) rather than waste time and effort trying to locate the few scattered gems that may have come out of the mainstream.

As I have written before on this blog, the first two years of the 1990s were when I became distanced from Hindi films (though a part of me loved the dhishum-dhishum and the familiar, reassuring structures) and sought nourishment elsewhere. I hadn’t read much film theory, had no concept yet of auteurs – like most young viewers, I mostly didn’t even think of films in terms of their directors. Yet, even at age 13, turning nastik and renouncing the mandir of Hindi movies, I knew that some of these films had a special energy in them and gave the impression that actual thought was taking place at the level of camerawork, scripting or performance; that an individual sensibility lay behind the whole. Mukul Anand was one such director (while

Hum

was the only film of his I whole-heartedly liked, there were stand-up-and-take-notice moments in nearly all his work, even in this tiresome thing called

Khoon ka Karz

). Another such director was J P Dutta, and one of my clearest memories from the summer of 1989 was watching Dutta’s

Hathyar

and sensing, without being able to articulate it, that I was seeing something more interesting than the regular action multi-starrer. Looking at tacky posters of Hathyar, with red-eyed Dharmendra and droopy-eyed Sanjay Dutt flaring nostrils and brandishing guns, you wouldn’t think it was any different from a dozen other khoon-aur-badlaa films that these actors were doing around the same time, but that would be an injustice to this layered work about the seductiveness of violence.

As I have written before on this blog, the first two years of the 1990s were when I became distanced from Hindi films (though a part of me loved the dhishum-dhishum and the familiar, reassuring structures) and sought nourishment elsewhere. I hadn’t read much film theory, had no concept yet of auteurs – like most young viewers, I mostly didn’t even think of films in terms of their directors. Yet, even at age 13, turning nastik and renouncing the mandir of Hindi movies, I knew that some of these films had a special energy in them and gave the impression that actual thought was taking place at the level of camerawork, scripting or performance; that an individual sensibility lay behind the whole. Mukul Anand was one such director (while

Hum

was the only film of his I whole-heartedly liked, there were stand-up-and-take-notice moments in nearly all his work, even in this tiresome thing called

Khoon ka Karz

). Another such director was J P Dutta, and one of my clearest memories from the summer of 1989 was watching Dutta’s

Hathyar

and sensing, without being able to articulate it, that I was seeing something more interesting than the regular action multi-starrer. Looking at tacky posters of Hathyar, with red-eyed Dharmendra and droopy-eyed Sanjay Dutt flaring nostrils and brandishing guns, you wouldn’t think it was any different from a dozen other khoon-aur-badlaa films that these actors were doing around the same time, but that would be an injustice to this layered work about the seductiveness of violence.This month marks 25 years since the film’s commercial release. Though it has a tiny cult following among knowledgeable buffs, it deserves to be better known; along with the director’s earlier Ghulami , it is the high point of an erratic but important career. Dutta’s work has always been prone to flab and overstatement – something that is most obvious in the star-studded Kshatriya and LOC Kargil – but these 1980s films nicely balanced the large canvas with the intimate moment. They used sprawling vistas in ways that did justice to the conceit of the 70 mm screen, while inhabiting these vistas with well-defined characters who had interiority. Looked at from a distance, they can seem like standard uber-macho sagas, but on closer examination they turn out to be thoughtful critiques of violence and how that violence is related to a feudal, patriarchal tradition and passed down until it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. There are strong roles for women as tempering influences or – in some cases – as facilitators for the more unsavoury aspects of tradition. And even while operating within the hyper-dramatic idiom of the commercial Hindi film, they successfully incorporated elements from outside that

world. Ghulami has Mithun Chakraborty as a wisecracking action hero (whose trademark line “koi shaq?” was guaranteed to draw front-bench whistles) but also has a side-track featuring parallel-cinema stars Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah as husband and wife who weigh mutual respect against ideological differences. And in Hathyar, the voice of conscience is played by someone who usually worked in a very different corner of the mainstream – Rishi Kapoor, whose presence here, in one of his best roles of the time, is a tip-off that this won’t be your regular action film.**

world. Ghulami has Mithun Chakraborty as a wisecracking action hero (whose trademark line “koi shaq?” was guaranteed to draw front-bench whistles) but also has a side-track featuring parallel-cinema stars Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah as husband and wife who weigh mutual respect against ideological differences. And in Hathyar, the voice of conscience is played by someone who usually worked in a very different corner of the mainstream – Rishi Kapoor, whose presence here, in one of his best roles of the time, is a tip-off that this won’t be your regular action film.**Memory can play tricks on us when it comes to old movies, but the lullaby that bookends Hathyar’s narrative turned out to be exactly as I remembered it when I saw the film again recently. In the opening shot a little boy, initially seen in silhouette, sits on a rocking horse as his thakur father sings to him about a prince who roams the world on a flying steed and returns home when he is tired. (“Ek raja ke bête ko lekar / Udne waala ghoda…”) They are interrupted by an uncle – a more militant member of the thakur’s clan – who gives the child a toy gun, against the father’s protests. Our Avinash won’t grow up to be a coward, the chacha says pointedly. “Aaj kal sharaafat ko hee kaayarta kehte hain,” (“These days decency is mistaken for cowardice”) the father sighs, trying to take the gun away from his boy, but the child is already enthralled, he won’t let go – “Nahin, hum kheleinge” are his chilling words – and the framing of the shot (which dissolves into the adult Avinash’s arms holding a real rifle) makes it seem like the weapon is an extension of his hand. The circle begun by these scenes will be completed in the film's final sequence, set in a toy shop where Avinash realises that running his blood-smeared palms over a plastic globe is the closest he will come to having the world in his hands or flying to exotic lands on a magic horse.

In the casting of Sanjay Dutt as a gun-obsessed young man who becomes a pawn in games played by larger forces, Hathyar weirdly pre-echoes real-world events. In cinematic terms though, it is a forerunner to Ram Gopal Varma’s

Satya

and other sleek, realistic city-crime films that would herald the multiplex era. Dutta’s early work was mostly set in villages and expanses of sunbaked desert where feudalism ran rampant and the line between rebel and daku, victim and aggressor, was erased. (Anyone who had the pleasure of watching Ghulami on a big screen – I have a dim childhood memory of this, though I may have nodded off during the Naseer-Smita scenes – will know how sweeping his visual sense was and how well he used these majestic settings.) But Hathyar was, literally, different terrain for him. Arriving in Bombay to escape village feuds, Avinash’s father is immediately confronted by violence and apathy of a different sort, though the hoodlums here are dressed in jeans and sneakers. “You said we’d move to the city to get away from the jungles, to live with civilised people,” Avinash’s mother (Asha Parekh in a good latter-day role) sarcastically tells her husband, “Well, here we are. Go and hug the cultured people you were so eager to meet.”

In the casting of Sanjay Dutt as a gun-obsessed young man who becomes a pawn in games played by larger forces, Hathyar weirdly pre-echoes real-world events. In cinematic terms though, it is a forerunner to Ram Gopal Varma’s

Satya