Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 18

July 4, 2021

On Mahanati, Maya Bazar and a “replica scene”

There was one thing I felt ambivalent about: the recreation of a couple of iconic moments from Maya Bazar, especially the brilliant “Aha Naa Pellanta” song sequence. This is an author-backed scene that Savitri had really sunk her teeth into, as she shifted between Sasirekha’s dainty gestures and Ghatotkacha’s manspreading (rakshasaspreading?) ones. (Context: Ghatotkacha, disguised as Sasirekha, is trying to maintain the appearance of a young woman singing about her upcoming nuptials.) This being among my favourite scenes in Maya Bazar, I enjoyed that Mahanati had paid a full-fledged tribute to it. But I couldn’t help wondering if it was the right decision from an actor’s point of view. For most of Mahanati, Keerthy Suresh is very good as Savitri (or rather, as the Savitri constructed by the film) – but in a studiously recreated scene like this, she is required to be more mimic than actor. In the original Maya Bazar scene, Savitri had the freedom to build her mannerisms and gestures from the inside-out, and it came across as joyful and spontaneous; the Mahanati version feels more schematic; one is uncomfortably aware that Keerthy has the onus of faithfully copying Savitri’s legendary act. And game though she is, if you have the original scene at hand and you know that the new scene

There was one thing I felt ambivalent about: the recreation of a couple of iconic moments from Maya Bazar, especially the brilliant “Aha Naa Pellanta” song sequence. This is an author-backed scene that Savitri had really sunk her teeth into, as she shifted between Sasirekha’s dainty gestures and Ghatotkacha’s manspreading (rakshasaspreading?) ones. (Context: Ghatotkacha, disguised as Sasirekha, is trying to maintain the appearance of a young woman singing about her upcoming nuptials.) This being among my favourite scenes in Maya Bazar, I enjoyed that Mahanati had paid a full-fledged tribute to it. But I couldn’t help wondering if it was the right decision from an actor’s point of view. For most of Mahanati, Keerthy Suresh is very good as Savitri (or rather, as the Savitri constructed by the film) – but in a studiously recreated scene like this, she is required to be more mimic than actor. In the original Maya Bazar scene, Savitri had the freedom to build her mannerisms and gestures from the inside-out, and it came across as joyful and spontaneous; the Mahanati version feels more schematic; one is uncomfortably aware that Keerthy has the onus of faithfully copying Savitri’s legendary act. And game though she is, if you have the original scene at hand and you know that the new scene

is meant to be a facsimile, a few little things won’t seem right: in a movement here, or an expression there, Keerthy comes across as more cerebral, more controlled than Savitri did in the original. (It was just a teeny bit like watching Sridevi dance to “Jumma Chumma” at that 1990 Wembley concert and thinking how different it was from the uninhibited energy of Kimi Katkar’s performance in the original.) It also struck me while watching this Mahanati scene that though so many films have been made about the making of earlier films (especially in the past two or three decades when cinema has been mining its own history with relish), it is still rare to see a recreation of this sort. The wiser move seems to be to try to capture the spirit or general tone of a character/scene rather than to do a straight imitation with the exact same camera angles and set design.

is meant to be a facsimile, a few little things won’t seem right: in a movement here, or an expression there, Keerthy comes across as more cerebral, more controlled than Savitri did in the original. (It was just a teeny bit like watching Sridevi dance to “Jumma Chumma” at that 1990 Wembley concert and thinking how different it was from the uninhibited energy of Kimi Katkar’s performance in the original.) It also struck me while watching this Mahanati scene that though so many films have been made about the making of earlier films (especially in the past two or three decades when cinema has been mining its own history with relish), it is still rare to see a recreation of this sort. The wiser move seems to be to try to capture the spirit or general tone of a character/scene rather than to do a straight imitation with the exact same camera angles and set design.

There are a couple of other such recreations in Mahanati itself – such as the wonderfully goofy moment in the “Vaarayo Vennilave” song from the 1955 film Missiamma where Gemini Ganesan is about to start singing the next stanza but clutches his throat, bemused, when a woman’s voice seems to emerge from it. (Savitri, standing behind him, has taken over the singing.) Mahanati’s recreation of that scene worked a little better for me, even though (or perhaps because) Dulquer Salmaan doesn’t look very much like Gemini Ganesan. Or maybe it worked because there are fewer layers involved here. In “Aha Naa Pellanta”, Savitri wasn’t just playing a singing princess, she was playing Ghatotkacha pretending to be Sasirekha and slipping in and out of character: this is a performance within a performance; an actor who does brilliantly in such a role tends to get canonised for all time, and no imitation can ever match it.

There are a couple of other such recreations in Mahanati itself – such as the wonderfully goofy moment in the “Vaarayo Vennilave” song from the 1955 film Missiamma where Gemini Ganesan is about to start singing the next stanza but clutches his throat, bemused, when a woman’s voice seems to emerge from it. (Savitri, standing behind him, has taken over the singing.) Mahanati’s recreation of that scene worked a little better for me, even though (or perhaps because) Dulquer Salmaan doesn’t look very much like Gemini Ganesan. Or maybe it worked because there are fewer layers involved here. In “Aha Naa Pellanta”, Savitri wasn’t just playing a singing princess, she was playing Ghatotkacha pretending to be Sasirekha and slipping in and out of character: this is a performance within a performance; an actor who does brilliantly in such a role tends to get canonised for all time, and no imitation can ever match it.

In the event that anyone is still reading this post: any thoughts about other cinematic recreations of this sort (in Indian or non-Indian films) and whether or not they have worked? I’m finding it surprisingly difficult – offhand the only one I can think of just now is from the 2012 film Hitchcock, with Scarlet Johansson as Janet Leigh as Marion Crane driving the car early in Psycho. But as I recall it, that was a fleeting moment. *** P.S. About authenticity in the Mahanati narrative. One thing I realised was off: the film’s implication that Gemini Ganesan was so wholeheartedly in love with Savitri that at least for the first few years of their marriage his attention was focused completely on her. In reality, Gemini’s extra-marital relationship with Pushpavalli was very much in high tide around the same time that he married Savitri in 1952: Gemini and Pushpavalli’s daughter, later famous as the actress Rekha, was born in October 1954.

In the event that anyone is still reading this post: any thoughts about other cinematic recreations of this sort (in Indian or non-Indian films) and whether or not they have worked? I’m finding it surprisingly difficult – offhand the only one I can think of just now is from the 2012 film Hitchcock, with Scarlet Johansson as Janet Leigh as Marion Crane driving the car early in Psycho. But as I recall it, that was a fleeting moment. *** P.S. About authenticity in the Mahanati narrative. One thing I realised was off: the film’s implication that Gemini Ganesan was so wholeheartedly in love with Savitri that at least for the first few years of their marriage his attention was focused completely on her. In reality, Gemini’s extra-marital relationship with Pushpavalli was very much in high tide around the same time that he married Savitri in 1952: Gemini and Pushpavalli’s daughter, later famous as the actress Rekha, was born in October 1954.  P.P.S. here is another fun little moment in Mahanati, where the dialogue (which you can see in the subtitle) feels like an inside joke. Because this is Naga Chaitanya playing his own grandfather, the legendary Akkineni Nageswara Rao (ANR).

P.P.S. here is another fun little moment in Mahanati, where the dialogue (which you can see in the subtitle) feels like an inside joke. Because this is Naga Chaitanya playing his own grandfather, the legendary Akkineni Nageswara Rao (ANR). (ANR was one of the superstars of Telugu cinema, but until a few years ago I knew nothing about him. Back then, the only way the inside reference in this scene would have made sense to me was if someone had told me that Nagarjuna’s son is playing Nagarjuna’s father.)

[A post about Maya Bazar is here]

June 30, 2021

Nostalgia post: on a Prakash Mehra-Bachchan audiocassette (and listening to films before watching them)

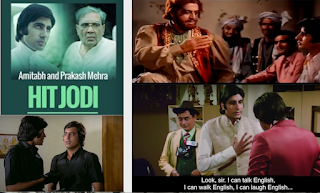

Which means the picture on the top left here is only a representative one, the closest I could locate online to the image I have held in my mind for decades: the cassette cover, which had a photo of the director Prakash Mehra (looking much younger than he looks in this “Hit Jodi” picture) alongside one of Amitabh Bachchan, each man in a separate square box. Most of my favourite audio-tapes of the early 80s (including one that was a Naseeb/Amar Akbar Anthony combination) had busy, colourful covers featuring the most popular stars – so it was strange to see this uncluttered cover, with a melancholy-looking Bachchan (probably from Muqaddar ka Sikandar) sharing space with a chubby man who was unlikely to be recognised by a casual movie viewer. (I definitely didn’t know who Prakash Mehra was when I first laid eyes on the cassette – I may have thought he was a playback singer like Kishore Kumar or Mohammed Rafi.) The tape was a collection of songs and dialogues from the films the two men did together, starting with the 1973 Zanjeer and continuing till the 1982 Namak Halaal. (Sharaabi, which came out in 1984, wasn’t included – the cassette pre-dated that film.) I spent a great deal of time listening to the songs, but also to the fragments of dialogue – the famous comic scene in Namak Halaal, for instance, with AB in a monologue about Wasim Bari and Wasim Raja and Vijay Merchant and Vijay Hazare and English being a very phunny language. One of my sheepish confessions as a movie buff is that I’m almost sure I heard most of the dialogue track of Sholay (on its famous double cassette) before I watched the film in its entirety. This was also the case with the films on the Bachchan-Mehra tape; it's likely that the first few times I listened to this cassette, I hadn’t watched any of the films in it. So I would try to piece together the stories of the films from the dialogues, and more often than not end up lost or confused. Some conjecturing was required, maybe some detective work too. When I heard “Yaari Hai Imaan Mera” from Zanjeer, it felt weird because the male playback voice didn’t sound like it could be for Amitabh – but when I heard part of the dialogue track on the same cassette (a confrontation between AB’s Vijay and Pran’s Sher Singh), I realised that Sher Khan must be doing the onscreen singing (Manna Dey got the voice just right). Similarly, having read in magazines about the 1970s rivalry between Bachchan and Vinod Khanna, I was curious about the storylines of Hera Pheri and Khoon Pasina, both of which featured on this cassette (Khoon Pasina was produced by Prakash Mehra, not directed by him). From the few dialogues available on the tape, I couldn’t for the life of me tell whether the AB and VK characters were friends or enemies in Hera Pheri, and this added to my curiosity about the film (and hastened the process of seeking it out to watch). And then there were the pain-soaked dialogues from Muqaddar ka Sikandar, including Bachchan’s references to Raakhee as “memsaab”, which became a motif in the film (in the same way that the more sarcastically uttered “sakhi” was a running thread in Bemisaal years later, with the same two actors). I remember being both intrigued and irritated by that repeated word “memsaab” – how did it fit if this was a romantic relationship? – and again, I had to wait to watch the film to make some sense of it.

Which means the picture on the top left here is only a representative one, the closest I could locate online to the image I have held in my mind for decades: the cassette cover, which had a photo of the director Prakash Mehra (looking much younger than he looks in this “Hit Jodi” picture) alongside one of Amitabh Bachchan, each man in a separate square box. Most of my favourite audio-tapes of the early 80s (including one that was a Naseeb/Amar Akbar Anthony combination) had busy, colourful covers featuring the most popular stars – so it was strange to see this uncluttered cover, with a melancholy-looking Bachchan (probably from Muqaddar ka Sikandar) sharing space with a chubby man who was unlikely to be recognised by a casual movie viewer. (I definitely didn’t know who Prakash Mehra was when I first laid eyes on the cassette – I may have thought he was a playback singer like Kishore Kumar or Mohammed Rafi.) The tape was a collection of songs and dialogues from the films the two men did together, starting with the 1973 Zanjeer and continuing till the 1982 Namak Halaal. (Sharaabi, which came out in 1984, wasn’t included – the cassette pre-dated that film.) I spent a great deal of time listening to the songs, but also to the fragments of dialogue – the famous comic scene in Namak Halaal, for instance, with AB in a monologue about Wasim Bari and Wasim Raja and Vijay Merchant and Vijay Hazare and English being a very phunny language. One of my sheepish confessions as a movie buff is that I’m almost sure I heard most of the dialogue track of Sholay (on its famous double cassette) before I watched the film in its entirety. This was also the case with the films on the Bachchan-Mehra tape; it's likely that the first few times I listened to this cassette, I hadn’t watched any of the films in it. So I would try to piece together the stories of the films from the dialogues, and more often than not end up lost or confused. Some conjecturing was required, maybe some detective work too. When I heard “Yaari Hai Imaan Mera” from Zanjeer, it felt weird because the male playback voice didn’t sound like it could be for Amitabh – but when I heard part of the dialogue track on the same cassette (a confrontation between AB’s Vijay and Pran’s Sher Singh), I realised that Sher Khan must be doing the onscreen singing (Manna Dey got the voice just right). Similarly, having read in magazines about the 1970s rivalry between Bachchan and Vinod Khanna, I was curious about the storylines of Hera Pheri and Khoon Pasina, both of which featured on this cassette (Khoon Pasina was produced by Prakash Mehra, not directed by him). From the few dialogues available on the tape, I couldn’t for the life of me tell whether the AB and VK characters were friends or enemies in Hera Pheri, and this added to my curiosity about the film (and hastened the process of seeking it out to watch). And then there were the pain-soaked dialogues from Muqaddar ka Sikandar, including Bachchan’s references to Raakhee as “memsaab”, which became a motif in the film (in the same way that the more sarcastically uttered “sakhi” was a running thread in Bemisaal years later, with the same two actors). I remember being both intrigued and irritated by that repeated word “memsaab” – how did it fit if this was a romantic relationship? – and again, I had to wait to watch the film to make some sense of it.

But something else from Muqaddar ka Sikandar became my favourite thing on the album: I grew to love “O Saathi Re” so much (I think the cassette had only the male version of the song) that for the first and last time in my life, aged 7 or 8, I made an effort to record my warbling, with the aid of a double-deck tape recorder. First I would play a couple of lines from the Mehra-Bachchan cassette in one deck, to grasp the words and the tune; then I would quickly switch it off and record myself on an empty cassette in the other deck. (I don’t remember any more about this, I was probably very unimpressed with the recording and deleted it quickly, and thus ended my singing career.) P.S. another song I really loved – the very first one on the cassette – puzzled me by its inclusion, because it wasn’t from a Bachchan film: “Chale Thhey Saath Milke” from Haseeena Maan Jaayegi, which Mehra had directed in 1968. At first I thought its inclusion was a mistake. Then I saw that the track listing had described this song as the “mukhda” for the album, but I had no idea what that meant: it was only later that I figured the lyrics were meant as a refrain, a tribute to the Mehra-Bachchan relationship, their “chalenge saath milkar” which spanned a decade’s worth of very popular films – and would eventually last till Jaadugar in the late 80s, a film that mercifully fell way outside the ambit of this collection. (I’m not sure I could have felt the same mushy affection for this audio-cassette if it had included that classic about an excited c̶o̶c̶k̶ rooster, “Padosan apni murgi ko rakhna sambhaal/ mera murga hua hai deewaana”.)

But something else from Muqaddar ka Sikandar became my favourite thing on the album: I grew to love “O Saathi Re” so much (I think the cassette had only the male version of the song) that for the first and last time in my life, aged 7 or 8, I made an effort to record my warbling, with the aid of a double-deck tape recorder. First I would play a couple of lines from the Mehra-Bachchan cassette in one deck, to grasp the words and the tune; then I would quickly switch it off and record myself on an empty cassette in the other deck. (I don’t remember any more about this, I was probably very unimpressed with the recording and deleted it quickly, and thus ended my singing career.) P.S. another song I really loved – the very first one on the cassette – puzzled me by its inclusion, because it wasn’t from a Bachchan film: “Chale Thhey Saath Milke” from Haseeena Maan Jaayegi, which Mehra had directed in 1968. At first I thought its inclusion was a mistake. Then I saw that the track listing had described this song as the “mukhda” for the album, but I had no idea what that meant: it was only later that I figured the lyrics were meant as a refrain, a tribute to the Mehra-Bachchan relationship, their “chalenge saath milkar” which spanned a decade’s worth of very popular films – and would eventually last till Jaadugar in the late 80s, a film that mercifully fell way outside the ambit of this collection. (I’m not sure I could have felt the same mushy affection for this audio-cassette if it had included that classic about an excited c̶o̶c̶k̶ rooster, “Padosan apni murgi ko rakhna sambhaal/ mera murga hua hai deewaana”.)

June 26, 2021

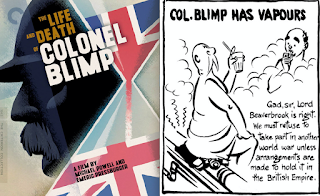

Well Begun: Colonel Blimp and the fountain of youth

For my First Post column about establishing sequences, here’s a look at a brilliant scene from Powell-Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp – and why it feels so personal at a time when I have been trying to write chronicles centred on the movie-watching summer of 1991

-----------------

“How do you know what sort of a fellow I was when I was as old as you are now?”

When we first meet Clive Wynne-Candy, the protagonist of the classic British film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, he is an old major-general, rotund and walrus-like in appearance, sweating heavily in a Turkish bath. He is also about to be ambushed by a group of young soldiers – his own countrymen – who are conducting a wartime training exercise. The scene is set during WWII (which is when the film was made in 1943), but Candy, being a veteran of much earlier conflicts including the Boer War, clings to old notions of valour and fair play. Now he is caught, literally and otherwise, with his pants down because he thought the training exercise would begin a few hours later, as had been agreed. But the youngsters retort that the current enemy, the Nazis, can’t be trusted to honour such pacts – the age of niceties and gentlemen’s agreements is long gone. They see Candy as a relic and mock him, while the walrus sputters indignantly at this impudence and lack of respect.

The scene is set during WWII (which is when the film was made in 1943), but Candy, being a veteran of much earlier conflicts including the Boer War, clings to old notions of valour and fair play. Now he is caught, literally and otherwise, with his pants down because he thought the training exercise would begin a few hours later, as had been agreed. But the youngsters retort that the current enemy, the Nazis, can’t be trusted to honour such pacts – the age of niceties and gentlemen’s agreements is long gone. They see Candy as a relic and mock him, while the walrus sputters indignantly at this impudence and lack of respect.

The Candy character is loosely modelled on David Low’s famous “Colonel Blimp” comic strip, which was meant to expose the pretensions of a stuffy and jingoistic old soldier. But as it happens, this film aims at a more fleshed out, multi-dimensional view of this man. It will take us into the past to show us the personal history of Candy over a period of four decades, spanning many forms of fighting and romance and friendship. And it will commence this movement with a beautiful, audacious scene.

During that Turkish bath confrontation, the enraged Candy runs after his chief tormenter, pushes the young man into the water, and plunges in after him. As they wrestle, he harrumphs:

“Puppy! Gangster! I was fighting for this country while your father was still in bum-freezers.The sound of those last three words comes to us as a bubbling echo, as if from a deep underwater cavern. The two men slip out of sight, an elegant camera glide leads us along the length of the pool… and culminates in the younger version of Clive Candy emerging from the other end.

[…] How do you know what sort of a fellow I was when I was as old as you are now… Forty Years Ago.”

A transition to four decades earlier has been made in a single unbroken take – no cuts or dissolves or fade outs or any of the other techniques that were traditionally used to mark the passage of cinematic time.

A transition to four decades earlier has been made in a single unbroken take – no cuts or dissolves or fade outs or any of the other techniques that were traditionally used to mark the passage of cinematic time. Weirdly, the other instance of something like this that comes to my mind is from a scene in the 1973 Hindi film Yaadon ki Baaraat. It’s one of those familiar scenes where a child is about to transform into the adult star, except that there’s nothing familiar about the way it’s done here. A boy on the run has just stopped to catch his breath atop a small bridge; the camera pans down to his legs and feet, then moves slowly through 360 degrees with nary a blink (as it does this, we see a train passing below; the only real movement within the frame). When it returns to its starting point, the same space is occupied by the adult version of the character, played by Dharmendra. Again, no cuts or dissolves, just the brilliant conceit that a simple camera movement lasting a few seconds can carry us across many years of narrative time.

Unusual as that moment in the Hindi film was, the Colonel Blimp scene predates it by three decades. Which should come as no surprise if you’re familiar with the splendidly inventive 1940s oeuvre of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who made this film as well as other classics: among them Black Narcissus, A Matter of Life and Death, A Canterbury Tale, The Red Shoes, and I Know Where I’m Going.

Re-watching those films last year in preparation for an online course I taught about Powell-Pressburger, I delighted again in the rich mingling of fantasy and reality, the inner life and the external one. One thing I emphasised in the course was the use of transitions in these films, including the shifts from the present to the past and back again. The “Forty years ago” pool scene is a notable one, but there are so many others. In one of my favourite films, A Canterbury Tale, a cut from a hawk soaring across the sky to a modern fighter plane in the same space takes us swiftly from the 14th century – the time of Chaucer’s Pilgrims – to the

present day. And in Black Narcissus, a nun posted at a convent in the Himalayas experiences little memory triggers – visual and aural ones – to her earlier, much more carefree life in Ireland. When Sister Clodagh (played by Deborah Kerr) hears the sound of a barking feral dog in the distance, we get an instant flashback to a horseback adventure with her boyfriend, hunting dogs scampering beside them; an overheard reference to a grandmother’s foot-stool similarly takes her back to a warm family gathering (and the frame shifts from a relatively subdued palette to something brighter, more saturated).

present day. And in Black Narcissus, a nun posted at a convent in the Himalayas experiences little memory triggers – visual and aural ones – to her earlier, much more carefree life in Ireland. When Sister Clodagh (played by Deborah Kerr) hears the sound of a barking feral dog in the distance, we get an instant flashback to a horseback adventure with her boyfriend, hunting dogs scampering beside them; an overheard reference to a grandmother’s foot-stool similarly takes her back to a warm family gathering (and the frame shifts from a relatively subdued palette to something brighter, more saturated).****

Scenes like these, as well as countless others, can’t be described in mere words; you really have to experience the magical world of Powell-Pressburger for yourself (in good prints and preferably on a largish screen). However, there is another reason why the Turkish bath scene in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp – and the old man’s grunted “Forty Years Ago” – strike a chord for me. This is why: in recent months I have been on many nostalgia dives of my own, some of them involving immersions into my old diaries from the early 1990s (Thirty Years Ago!), which was a pivotal time for me as a movie buff developing new tastes and entering uncharted worlds.

As I negotiate the turbulent waters of those diaries, I feel a bit like Candy entering the bath and coming out at the other end. I encounter a different version of myself, and the world has of course changed too. It is the world of 1991, with economic liberalisation around the corner and satellite TV about to change our viewing habits forever. I have recently become obsessed with old American and British cinema, and in the process become even more solitary than before, cut off from my friends who don’t share such interests. The internet is still many years away, and one has to work hard not just to get prints of such films but also to acquire any details about them from embassy libraries or from movie guides in second-hand bookstores. CD-ROMs containing useful information are in the near future, but it is beyond imagining that a day might come when one can interact in real time, through a computer, with other movie buffs based around the world.

As I negotiate the turbulent waters of those diaries, I feel a bit like Candy entering the bath and coming out at the other end. I encounter a different version of myself, and the world has of course changed too. It is the world of 1991, with economic liberalisation around the corner and satellite TV about to change our viewing habits forever. I have recently become obsessed with old American and British cinema, and in the process become even more solitary than before, cut off from my friends who don’t share such interests. The internet is still many years away, and one has to work hard not just to get prints of such films but also to acquire any details about them from embassy libraries or from movie guides in second-hand bookstores. CD-ROMs containing useful information are in the near future, but it is beyond imagining that a day might come when one can interact in real time, through a computer, with other movie buffs based around the world. In the decades since then, I have been fortunate enough to have had many online and offline conversations about cinema with a variety of people – including some young students who are genuinely curious about old films. But there are also times when I feel like an old fogey, waxing on about things that seem to have little relevance to today’s viewers. With countless new films and web series being released each week across a host of OTT platforms, when there is so much competing for a movie nerd’s attention (and when even someone who has the luxury of 12 hours’ viewing time per day might feel overwhelmed by watch-lists), how does one meaningfully curate thousands of films across genres and categories that are 60, or 80, or 100 years old? And how does one argue with a “woke” viewer who firmly believes that old films were regressive products of a backward age, that they might have some value as artefacts but can’t really “teach” us anything today?

The pragmatic answer for me is: keep trying. Write about such films in columns, host online discussions about them once in a while, hope that I might get a few people as engaged with these things as I was thirty years ago. Wrestle in the pool of argument and opinion, dunk the head of a “young un” under water if you need to, hope to infect others with your passion. But in doing all this, try not to be a boastful old blimp.

[Earlier First Post columns are here. And here is an old piece about A Canterbury Tale]

June 20, 2021

Talking movies (and other things) on Amit Varma's podcast

Still, we’ll do a follow-up conversation at some point. And there should be some things of interest in this one too, for those of you who have the time/patience to listen to a long chat between two people who first met during the heady, pre-social-media days when blogs were the most exciting things on the internet.

P.S. the recording itself was done as a video chat so that we would have visual cues, allowing the conversation to proceed smoothly. Early on, as Amit and I were filling our coffee cups, we realised the cups had a weirdly similar colour scheme - so Amit took this screenshot for posterity.

P.S. the recording itself was done as a video chat so that we would have visual cues, allowing the conversation to proceed smoothly. Early on, as Amit and I were filling our coffee cups, we realised the cups had a weirdly similar colour scheme - so Amit took this screenshot for posterity.(On the other hand, our tastes in cinema sometimes differ drastically, as you can tell from parts of the conversation. Poor Amit must be traumatised by how many of his recent guests have turned out to be Sanjay Leela Bhansali defenders!)

June 7, 2021

In memory of a sports-loving dog

These aren't flattering photos, but never mind. This is one of our colony dogs, Noorie, who was taken to the Animals First clinic (in Chhatarpur) a few days ago with a serious kidney condition. She passed away early yesterday. She was old, the blood reports had been very bad, and she had been vomiting constantly, not retaining food over the past few days. A few of us, including the woman who used to feed her, had decided — in consultation with a vet — that it was time to put her out of her suffering, but she went on her own. We cremated her at Sai Ashram in the afternoon. I didn’t know Noorie well — in fact I didn’t even know she was called Noorie by those who interacted with her regularly. I thought of her as "Kaajal" because that was the name given to her by someone I knew — it was a natural fit because she had very distinctive black eyes in her prime, with the colour appearing to spill over like thickly applied kohl.

These aren't flattering photos, but never mind. This is one of our colony dogs, Noorie, who was taken to the Animals First clinic (in Chhatarpur) a few days ago with a serious kidney condition. She passed away early yesterday. She was old, the blood reports had been very bad, and she had been vomiting constantly, not retaining food over the past few days. A few of us, including the woman who used to feed her, had decided — in consultation with a vet — that it was time to put her out of her suffering, but she went on her own. We cremated her at Sai Ashram in the afternoon. I didn’t know Noorie well — in fact I didn’t even know she was called Noorie by those who interacted with her regularly. I thought of her as "Kaajal" because that was the name given to her by someone I knew — it was a natural fit because she had very distinctive black eyes in her prime, with the colour appearing to spill over like thickly applied kohl.

She was a solitary creature, seemingly not fond of other dogs, making sure no one encroached on the small park where she lived, outside our local BSES office. But I did briefly see a more social side when she took a liking to my Lara a few years ago. If she saw us from a distance, she would hesitantly trot across to our park to say a very quick hello, lick Lara a couple of times, and then scoot back just as nervously — as if sheepish about having over-stayed her welcome. She seemed to be quite tolerant of humans though. I have taken many photos of colony dogs doing amusing things, expressing various shades of personality, but there are just as many memorable images that I never managed to capture. Among these: Noorie/Kaajal sitting right in the middle of the BSES park while youngsters noisily played cricket or football around her. When it was a cricket match, I used to think of her as the umpire, because that’s always where she seemed to be sitting, near the end of the bowler’s run-up. It was a remarkable sight, and she always looked very poised and content in this role. (I never actually saw her get hit by a ball, but I'm told that when this happened once in a while, her response was never more than a short and stoical yelp; she didn’t get up or run away. Unfailingly professional, a Dickie Bird of her species.) [

Related post: Sona, in remembrance

]

She was a solitary creature, seemingly not fond of other dogs, making sure no one encroached on the small park where she lived, outside our local BSES office. But I did briefly see a more social side when she took a liking to my Lara a few years ago. If she saw us from a distance, she would hesitantly trot across to our park to say a very quick hello, lick Lara a couple of times, and then scoot back just as nervously — as if sheepish about having over-stayed her welcome. She seemed to be quite tolerant of humans though. I have taken many photos of colony dogs doing amusing things, expressing various shades of personality, but there are just as many memorable images that I never managed to capture. Among these: Noorie/Kaajal sitting right in the middle of the BSES park while youngsters noisily played cricket or football around her. When it was a cricket match, I used to think of her as the umpire, because that’s always where she seemed to be sitting, near the end of the bowler’s run-up. It was a remarkable sight, and she always looked very poised and content in this role. (I never actually saw her get hit by a ball, but I'm told that when this happened once in a while, her response was never more than a short and stoical yelp; she didn’t get up or run away. Unfailingly professional, a Dickie Bird of her species.) [

Related post: Sona, in remembrance

] June 5, 2021

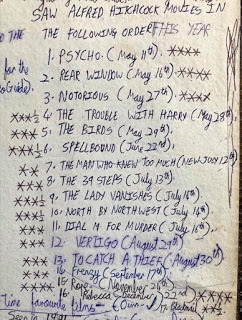

The 1991 case-files: two real-life murders (and a few movies)

[Continuing the nostalgia/memory project that I referred to in this recent post about Ajooba] Another despatch from the summer of 1991. As I have written earlier, that summer was a pivotal one for my film education – this being when I first developed an obsession with old American and British cinema that also led me to serious film literature for the first time. (Since I am still very much a young film student in my own head, it’s strange to think that a full 30 years have passed since the months when I lugged my heavy Leonard Maltin movie guide around with me to neighbourhood video shops, or to Palika Bazaar once in a while, and looked at movie entries in the book before deciding what to rent or buy.)

Another despatch from the summer of 1991. As I have written earlier, that summer was a pivotal one for my film education – this being when I first developed an obsession with old American and British cinema that also led me to serious film literature for the first time. (Since I am still very much a young film student in my own head, it’s strange to think that a full 30 years have passed since the months when I lugged my heavy Leonard Maltin movie guide around with me to neighbourhood video shops, or to Palika Bazaar once in a while, and looked at movie entries in the book before deciding what to rent or buy.)

Some memories of the April to July period in particular are very vivid, and are supplemented by – or in some cases, contradicted by – my diary entries of the time. These include two other signposts: two killings that took place a little over three weeks apart. The first of them – the Rajiv Gandhi assassination on May 21 – everyone knows about. The second was much less public but created lasting shockwaves for my mother’s family: the murder of my great-grandmother – my nani’s mother who, for whatever reason, was known to all of us as “bhabhiji” – in her Nizamuddin house on June 14.

Looking back, both these incidents are inseparable in my mind from the ferocious movie-watching I was doing at the time – and the many ways in which I was processing or making sense of real life through films (while also being aware of the differences between the two things).

On the night of May 21, my nani was staying with us in Saket. (She divided her time between Saket and Green Park, where she had lived for years with an old friend, a reserved, silver-haired gentleman whom I knew as Badhwar uncle – and in whose house my mother and I had also lived for a year in 1986-87 when we moved out of my father’s place – but more on that another time.) Though my summer holidays had begun, we must have all gone to bed by 10-10.30 pm; this would be the last year of the Doordarshan era, and we weren’t in the habit of watching TV till late. And so, it was only at around 5.30 the next morning that we were woken by a call from Badhwar uncle, telling us about the assassination.

As my nani told it, his voice was shaking on the phone, and this wasn’t just because of the magnitude of what had happened. Badhwar uncle, who practised astrology (very seriously but non-professionally, only counselling acquaintances who came to him for advice), had once predicted that not only would Rajiv Gandhi not live to see 1992, but that his death would be so terrible that his face wouldn’t be left intact enough for identification.

I grew up to be an astrology-sceptic myself (and didn’t find it too interesting even as a child, having eye-rolled my way through parts of a Linda Goodman book my mother had lying around), but I had heard uncle make that prediction years earlier – possibly during the time when my mother and I lived in his Green Park house. And when I met him for the first time after the Rajiv Gandhi killing, he looked strained by the way in which it had come to pass; there was no gloating, no “didn't I tell you”, just tiredness.  This was my most first and most immediate association with the death of the young, pleasant-looking prime minister, but others came soon. Starting with the photographs in India Today and Frontline (it is still hard to believe today that they were printed in such widely read magazines that must have been lying around lakhs of houses for anyone, including children, to pick up). Those images of blood and gore and dismemberment and numbed survivors wading through slush (followed a week or two later by a particularly macabre picture of the reconstructed limbs of the suicide bomber) were my first direct acquaintance with what a bomb could do to a human body; this was the real thing, so removed from the glamorous explosions and sanitised aftermaths one got to see in action sequences in films. As someone who turned often to cinematic reference points even back then, I remember looking at these gruesome pictures and reflecting that the little girl in Mr India who was blown up by a stuffed toy – after she picked the thing up – would definitely not have been left in a state that allowed Anil Kapoor to lift her whole and rush her to a hospital in desperate hope of saving her.

This was my most first and most immediate association with the death of the young, pleasant-looking prime minister, but others came soon. Starting with the photographs in India Today and Frontline (it is still hard to believe today that they were printed in such widely read magazines that must have been lying around lakhs of houses for anyone, including children, to pick up). Those images of blood and gore and dismemberment and numbed survivors wading through slush (followed a week or two later by a particularly macabre picture of the reconstructed limbs of the suicide bomber) were my first direct acquaintance with what a bomb could do to a human body; this was the real thing, so removed from the glamorous explosions and sanitised aftermaths one got to see in action sequences in films. As someone who turned often to cinematic reference points even back then, I remember looking at these gruesome pictures and reflecting that the little girl in Mr India who was blown up by a stuffed toy – after she picked the thing up – would definitely not have been left in a state that allowed Anil Kapoor to lift her whole and rush her to a hospital in desperate hope of saving her.

Later there was the televised funeral, with the glimpses of Amitabh Bachchan in white kurta-pyjama standing near the pyre – it was strange to see AB on screen in this context, so different from the last two times I had seen him, in Hum and Ajooba earlier in the year. At a time when I was slowly moving away from the grand idiom of the Hindi cinema I had loved for years, this moment was another reminder that a superstar may be an all-avenging Tiger or a swashbuckling Arabian prince on screen (or a Supremo in a comic strip) but a bowed and helpless mourner, looking much smaller than life, at the funeral of a friend who couldn’t be saved even though he was the most powerful man in the country.

Though this messy real-life killing, and the way it played out on our TV screens and in the pages of news magazines, dominated our thoughts for several days, a more personal tragedy soon followed.

On the afternoon of June 14, while my nani played cards with a couple of her friends at our dining table, I was in the video room watching the 1974 film of Murder on the Orient Express. The film held no surprises for me as a mystery, since I had read the Agatha Christie book much earlier, but I was very interested in it for its large ensemble cast. This was in the first couple of months of my obsession with old Hollywood stars, which included leafing for hours each day through the Maltin guide and making my own filmography lists – and “multi-starrers” (to use the Hindi-movie term) held a special attraction since they allowed me to deepen my acquaintance with many different actors at the same time. Ensemble films or epics like Judgement at Nuremberg, Spartacus, The Longest Day and How the West Was Won had served this function over the previous few weeks. Though Murder on the Orient Express wasn’t an “old” film by my standards, it was useful for bringing together such disparate giants as Ingrid Bergman and John Gielgud and Wendy Hiller and Lauren Bacall and Richard Widmark (as well as the “younger” stars like Sean Connery, Vanessa Redgrave and one of my biggest crushes, Anthony “Norman Bates” Perkins).

Shortly after I began watching the film, I became vaguely aware that my nani was feeling uneasy in the room outside, and her friends were asking her if everything was okay and asking my mother to bring her a glass of water; but things settled down and I figured it was a bit of drame-baazi as distraction because she was losing her card game.

Less than an hour later, the phone call came. My mother answered it, spoke monosyllabically for a few seconds (with my nani yelling “Kaun hai? Kaun hai?” from a distance as she tended to). Then mum put down the phone and said, in a deadpan voice, getting straight to the point, no softening of the blow: “Bhabhiji ka murder ho gaya hai.”

On my TV screen, Hercule Poirot was interrogating the Russian princess. I registered what my mother had said, along with the wheezing gasps and groans that had started to come from nani (the contrast between the tone of the announcement and the tone of the response was like the difference between a studiously understated Nordic noir and a Sivaji Ganesan mythological), and realised I’d have to stop the film and go to play my own part in this real-world theatre. Over the days that followed – going for the funeral, visiting the Nizamuddin house a couple of times, hearing much grisly speculation about what had happened – I found myself playing the part of Albert Finney’s Poirot in my head. I can’t provide too many details here, but suspicion danced around a couple of members of the deceased woman’s enormous family (which was made up of a dozen children, of whom my nani was the oldest, and many more grandchildren). As little details about fingerprints and unusual sightings and unidentified strangers and contradictory claims and property issues emerged, I imagined my Poirot self in a large room, interrogating members of my big fat Punjabi extended family (in what would have been a very incongruous Belgian accent given the circumstances) – with several “a-ha!” moments as I noted an incongruous statement here, an overlooked clue there, and generally had a roomful of grand-uncles and grand-aunts gaping at my intellectual brilliance.

Over the days that followed – going for the funeral, visiting the Nizamuddin house a couple of times, hearing much grisly speculation about what had happened – I found myself playing the part of Albert Finney’s Poirot in my head. I can’t provide too many details here, but suspicion danced around a couple of members of the deceased woman’s enormous family (which was made up of a dozen children, of whom my nani was the oldest, and many more grandchildren). As little details about fingerprints and unusual sightings and unidentified strangers and contradictory claims and property issues emerged, I imagined my Poirot self in a large room, interrogating members of my big fat Punjabi extended family (in what would have been a very incongruous Belgian accent given the circumstances) – with several “a-ha!” moments as I noted an incongruous statement here, an overlooked clue there, and generally had a roomful of grand-uncles and grand-aunts gaping at my intellectual brilliance.

But of course, in real life, there were to be no epiphanies or denouements of that sort. The case petered out after a while, things were brushed under the carpet or rationalised away, life moved on. There was much bad blood among some members of the family for a while – some resentments and suspicions lasted in one form or the other for decades – but nothing like a full-fledged severing of ties or a full-fledged reconciliation. Those sorts of resolutions I continued to find in the thrillers I read and the suspense films I watched. (In the weeks between the two murders, I had watched a few Hitchcock films for the first time – among them Notorious, The Trouble With Harry, and The Birds. There was also a short and uncharacteristic dalliance with a few of the Roger Moore James Bond films.)

The uncertainty of those times – at the personal and political level – is reflected in two “by the way” postscripts in one of my diary entries near the end of June:

“By the way: **** uncle dropped by in the afternoon, dropped some more dark hints about **** uncle, and then left. It didn’t seem to matter to anyone though, and soon we were talking about other things.”

“By the way 2: Narsimha Rao is the prime minister now. Wonder who it will be tomorrow evening.”

-------------------

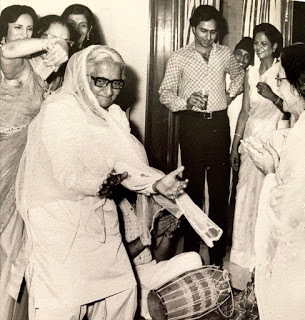

P.S. the last time I met my great-grandmother – or “bhabhiji” – was a couple of weeks after RG’s death, and 10 days before her own, when she came to our Saket flat with one of nani’s sisters who was visiting Delhi. My diary tells me the date was June 4, but there aren’t any other details given; what I do clearly remember is my nani showing her mother those grisly assassination-scene photos in Frontline and India Today, discussing them using not-very-refined Punjabi phrases (and with a very Punjabi relish).

[Earlier posts about 1991: awaiting Ajooba; and my Leonard Maltin movie guide. And on Facebook, here is a public post about my learning of Satyajit Ray’s adolescent journal-writing, which I could identify with]

May 26, 2021

Sword and razor: thoughts on Karnan and Mandela

(Did this piece about two fine new Tamil films for Mint)

-----------------------------------

The first time we meet the protagonists of Mari Selvaraj’s Karnan and Madonne Ashwin’s Mandela, they are fast asleep. Both Karnan (Dhanush) and Mandela (known mainly as “Jackass” at this point, and played by the affable Yogi Babu) are about to be rudely woken for banal reasons. But more urgent awakenings are soon to follow.

The first time we meet the protagonists of Mari Selvaraj’s Karnan and Madonne Ashwin’s Mandela, they are fast asleep. Both Karnan (Dhanush) and Mandela (known mainly as “Jackass” at this point, and played by the affable Yogi Babu) are about to be rudely woken for banal reasons. But more urgent awakenings are soon to follow.Here are two films about lower-caste men faced with oppression and hegemony, attaining a form of political consciousness and emerging as village heroes. Their arcs are very different, though, as is the tone and emphasis of the narratives they inhabit. Karnan, inspired by a real-life police attack on a Dalit village in 1995, is a more overtly “serious” film, certainly edgier and angrier, about a whole community under threat. Mandela is a laidback, good-natured parable, with traces of dark satire, about an individual: a village barber who becomes important during a local election.

Depending on how you look at the films, there are as many similarities as differences. For instance, both have moments where papers are destroyed, or threatened with destruction, emphasising what these documents mean to people for whom this is a sole stamp of identity, a validation of existence. And in each story, there is an inspirational figure whose life serves as a palimpsest for the hero’s (though neither film underlines the connection too much, and a one-to-one mapping isn’t useful beyond a point).

In Karnan, this spiritual forebearer is from mythology – the Mahabharata’s Karna, denigrated as a low-caste man even after being gifted an elevated status. In Mandela, the connection is with a contemporary figure, Nelson Mandela, and is first presented in comical terms. When “Jackass” (also called “Smile” or “Bushy Hair” or “Dung Picker” – he never finds out his real name, he only knows his caste, which is the essential marker) applies for an Aadhaar card, a friendly postal officer gives him a few famous names to choose from. One of these is Mandela, who, she points out, fought for the identity of black people “just like you are fighting for your identity”.

Our man doesn’t care about that, he finds the South African leader appealing because “he has curly hair and dark skin like me”. Liberating his people, or himself, isn’t on his mind – his ambitions are small, he would be content if he were occasionally paid for the menial jobs he is ordered to do. But the voter’s ID card sets wheels in motion; as an election campaign reaches fever pitch, Mandela becomes a deadlock-breaker between warring factions, and now suddenly everyone is trying to pamper him. The people who once made him clean toilets and were incensed at the thought of him sitting in their car now use the vehicle to help him get down from a tree, and even clutch at his feet as he descends. All this adds up to a quietly humorous tale about upward mobility and politics of convenience.

Our man doesn’t care about that, he finds the South African leader appealing because “he has curly hair and dark skin like me”. Liberating his people, or himself, isn’t on his mind – his ambitions are small, he would be content if he were occasionally paid for the menial jobs he is ordered to do. But the voter’s ID card sets wheels in motion; as an election campaign reaches fever pitch, Mandela becomes a deadlock-breaker between warring factions, and now suddenly everyone is trying to pamper him. The people who once made him clean toilets and were incensed at the thought of him sitting in their car now use the vehicle to help him get down from a tree, and even clutch at his feet as he descends. All this adds up to a quietly humorous tale about upward mobility and politics of convenience. Karnan is, structurally and tonally, more complex. It shifts between a mythical mode – riven with symbolism, rousing music, a few stylish setpieces – and a grounded narrative located in the here and now. The opening sequences have the texture of deep myth: a bird’s eye view of a girl dying on a road, passing vehicles ignoring her, until she is depicted as a supine figure with a goddess’s mask – followed by a vivid opening-credits song with a montage of people calling out to Karnan the saviour. All this might lead you to expect a larger-than-life story about a superhero’s journey, but this is a slow-burn film about a few incidents (mostly centred around the absence of a bus stop for a small village) that lead to a small revolt – which then becomes bigger when the local police respond with cruelty. And though Karnan himself performs a dramatically impressive “fish-cutting” feat with a sword early on, he isn’t a grand or distant figure: he is just one of the villagers – a boy of the soil, son, kid brother (often scolded by his big sister), friend, lover. Dhanush’s down-to-earth persona emphasises this, even after circumstances force Karnan into a proactive role.

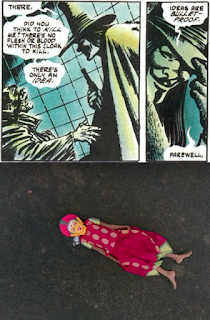

This film is very aware of two contrasting approaches to societal change: the slow, incremental one (like Karnan painstakingly using a jagged rock to fray the rope binding a donkey’s feet in a key scene) and a decisive call to revolution, where sticks and swords may be brandished and bus windows and bones broken. Ultimately, it seems to cast its lot with the latter approach, and this results in a climactic sequence that could have come from a more conventional action film. But the recurring motif of the long-dead girl with the mask, stirring the villagers in their revolt, is reminiscent of the powerful ending of Pa. Ranjith’s Kaala, in which the appearance of many Kaalas (or Kaala masks) suggest a hero being alive in the spirit of those whom he inspired. Both sequences also evoke the underlying premise of Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta: that it doesn’t matter which face lies behind the revolutionary’s mask; individuals may be killed but the idea is imperishable.

This film is very aware of two contrasting approaches to societal change: the slow, incremental one (like Karnan painstakingly using a jagged rock to fray the rope binding a donkey’s feet in a key scene) and a decisive call to revolution, where sticks and swords may be brandished and bus windows and bones broken. Ultimately, it seems to cast its lot with the latter approach, and this results in a climactic sequence that could have come from a more conventional action film. But the recurring motif of the long-dead girl with the mask, stirring the villagers in their revolt, is reminiscent of the powerful ending of Pa. Ranjith’s Kaala, in which the appearance of many Kaalas (or Kaala masks) suggest a hero being alive in the spirit of those whom he inspired. Both sequences also evoke the underlying premise of Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta: that it doesn’t matter which face lies behind the revolutionary’s mask; individuals may be killed but the idea is imperishable. In the Mahabharata, when Karna is offered a chance to broker peace by revealing his true identity, he rejects the offer partly because he knows that hostilities have already gone too far; that a cleansing war is needed, which requires that he remain a foot-servant to the larger cause. Karnan’s situation is different in the specifics, but there is a poetic similarity in his decisions: after passing a military test, he has the opportunity to join the establishment – perhaps positively representing his community in the process, and helping to improve their lot over time – but he opts for swifter, more decisive action.

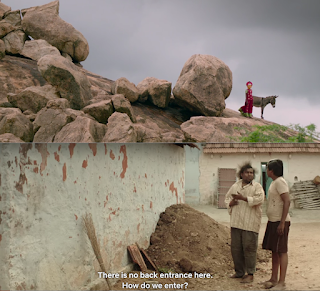

Given its more modest canvas and very specific story (about an individual who has to figure out his own journey rather than be a leader or totem), Mandela doesn’t have to deal with such epic conflicts. It has some faith in the idea that slow change can work, that the system can be benevolent and supportive. There is a very droll moment where we see Mandela and his friend staring blankly at a wall for a few seconds; the payoff is that this is the back of the post-office building and they are wondering how to get in because there is no rear entrance for low-castes. You can come in from the front, says the smiling officer, a woman who is fighting her own small battles for a more egalitarian world. Given that this is an official space, there is an implication here that the authorities are trying to move past old discriminations. And the film’s final scene is an unapologetically idealistic, optimistic one that might discomfit those who believe there is no room for sugar-coating in depictions of the caste struggle.

Given its more modest canvas and very specific story (about an individual who has to figure out his own journey rather than be a leader or totem), Mandela doesn’t have to deal with such epic conflicts. It has some faith in the idea that slow change can work, that the system can be benevolent and supportive. There is a very droll moment where we see Mandela and his friend staring blankly at a wall for a few seconds; the payoff is that this is the back of the post-office building and they are wondering how to get in because there is no rear entrance for low-castes. You can come in from the front, says the smiling officer, a woman who is fighting her own small battles for a more egalitarian world. Given that this is an official space, there is an implication here that the authorities are trying to move past old discriminations. And the film’s final scene is an unapologetically idealistic, optimistic one that might discomfit those who believe there is no room for sugar-coating in depictions of the caste struggle.  This is eventually a key difference between the films: Mandela gets legitimacy and a bit of power through a government-issued document (which he doesn’t have to struggle too hard to obtain) while Karnan turns his back on a state offer. One man will continue to work patiently with his shaving razor, even in a final dramatic sequence where almost the entire village is gathered around him and the election results are trickling in; the other will take up a sword because a jagged stone isn’t enough when you have to hew right through a big fish – or a societal structure.

This is eventually a key difference between the films: Mandela gets legitimacy and a bit of power through a government-issued document (which he doesn’t have to struggle too hard to obtain) while Karnan turns his back on a state offer. One man will continue to work patiently with his shaving razor, even in a final dramatic sequence where almost the entire village is gathered around him and the election results are trickling in; the other will take up a sword because a jagged stone isn’t enough when you have to hew right through a big fish – or a societal structure. -----------------

P.S. amusingly – and perhaps inevitably – one other thing these two films have in common is a Rajinikanth homage. The first time we are about to meet “Jackass”, the camera panning over the tools of his trade, there is an image of the superstar on the board that says Barber Shop; meanwhile Karnan wears a T-shirt with an image of the Rajinikanth of Thalapathi – another film about a contemporary Karna figure. (A post about it is here.)

Related posts: on Mari Selvaraj's Pariyerum Perumal; on Nagraj Manjule's Sairat; on Anubhav Sinha's Article 15

May 20, 2021

On the lovely documentary My Octopus Teacher (and why it personally resonated with me)

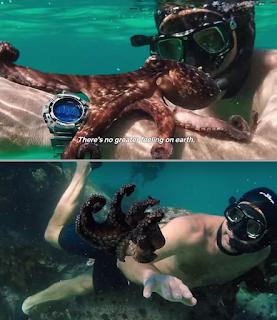

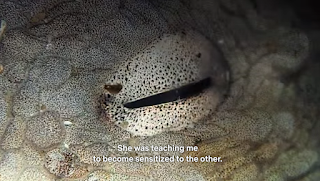

Last year, while writing a piece for an anthology, I had occasion to think about the part-time dogs in my life. “Part-time” defined as the four or five street dogs whom I feed, vaccinate and look out for in case there’s a medical emergency, but whom I can’t monitor around the clock – they are not house dogs, they treasure their independence, and have long been acclimatised to an outdoor life and routine. There are gradations here, of course: a few of these dogs have never come inside the house; one of them used to be mainly on the streets but now, in her old age, spends most of her time indoors. And then there’s Chameli, who spends a chunk of the day inside (and stays the whole night in winters) but has other friends to meet and peacocks to chase and obligations to keep; she might go missing for a full day or two at times, and when that happens I have to deal with the idea that something bad might happen to her – while crossing the main road, for instance – and that I might not be able to deal with it immediately.  If you’re a responsibility-junkie and have a strong bond of this sort with a wild creature (or part-time-wild creature), it is a source of much worry. So I felt an immediate connect with a sequence of events midway through the Oscar-winning Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher. Filmmaker Craig Foster, free-diving in an underwater forest off the South African coast, has developed an unexpected and mysterious bond with an octopus who has gradually come to trust him and accept his presence in her world. Enchanted, he goes to meet her every day. After witnessing an attack from a pajama shark that leaves one of her arms severed, and realizing how precarious her state is, he worries about being unable to meaningfully help. Back on land, in his house, a universe away from her sub-aquatic kingdom, he thinks constantly about her, wonders what she is up to, whether she is safe. “You just want to visit her every day and see what’s going on,” he tells us reticently. What that really means: he wishes he could keep an eye on her all the time, keep a protective cocoon around her.

If you’re a responsibility-junkie and have a strong bond of this sort with a wild creature (or part-time-wild creature), it is a source of much worry. So I felt an immediate connect with a sequence of events midway through the Oscar-winning Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher. Filmmaker Craig Foster, free-diving in an underwater forest off the South African coast, has developed an unexpected and mysterious bond with an octopus who has gradually come to trust him and accept his presence in her world. Enchanted, he goes to meet her every day. After witnessing an attack from a pajama shark that leaves one of her arms severed, and realizing how precarious her state is, he worries about being unable to meaningfully help. Back on land, in his house, a universe away from her sub-aquatic kingdom, he thinks constantly about her, wonders what she is up to, whether she is safe. “You just want to visit her every day and see what’s going on,” he tells us reticently. What that really means: he wishes he could keep an eye on her all the time, keep a protective cocoon around her.

I know what that feels like. But if I could be so worried about Chameli and other dogs – despite knowing that we occupy the same physical environment, and that they were unlikely to be any further than, say, a 100-metre radius or a five-minute walk from my building – how much more nerve-wracking it must have been for Foster to feel this concern for a creature that inhabits another world altogether: a world that he himself can visit for only short durations, and never quite grasp the full workings  of. (There were times, he says in the film, when he thought about trying to chase the sharks away – but of course he knew he couldn’t really do that; even if there were a way of keeping all the octopus’s predators away, it would mean interfering with an ecosystem, interfering with the strange and savage ways of Nature. And who knows what consequences there might be? Including some that could in the long run be hazardous for his eight-limbed friend.)

of. (There were times, he says in the film, when he thought about trying to chase the sharks away – but of course he knew he couldn’t really do that; even if there were a way of keeping all the octopus’s predators away, it would mean interfering with an ecosystem, interfering with the strange and savage ways of Nature. And who knows what consequences there might be? Including some that could in the long run be hazardous for his eight-limbed friend.)

Given its setting, it goes without saying that My Octopus Teacher is visually extraordinary. The multiple camera angles and high-resolution images of the submarine world in which Foster immerses himself (initially as a form of self-therapy) are reminders of how much more is technically possible today compared to when Jean Painleve made the first of his famous octopus films nearly a century ago. (Anyone interested in those wonderful short films, check Mubi India.) But My Octopus Teacher is also a reminder, as Foster says, that we humans know so little about the workings of underwater life – that incredible new discoveries are still being made every week, established wisdom overturned, and there is potential for so much more exploration. This really is an alien world, and connecting with it – and occasionally communicating with it – is one of the most moving and humbling things that our self-absorbed species can do.  A couple of the film's most powerful scenes involve physical contact between Foster and the octopus: her reaching out for his fingers for the first time; then, more trustingly, “riding” his hand all the way to the water’s surface. These encounters, and his description of them, were a throwback for me to one of the most magical moments I have experienced, during a 20-minute sea-bed walk in the Andamans nearly a decade ago. There were many wonders: dazzling corals, bright orange clownfish flitting in and out of their sea anemones, a motionless but vicious-looking creature that seemed entirely made up of sharp teeth, an outtake from one of HP Lovecraft’s storyboards. But the transcendental moment came when the guides gave us mashed bread to feed a big school of black-and-yellow fish that had been swimming nearby. I must have been a little late in letting go of some of the food, because as the creatures swarmed around us I felt dozens of little mouths nibbling and sucking at my fingers. For just a second or two. But nothing prepares you for the frisson that comes with an experience like this.

A couple of the film's most powerful scenes involve physical contact between Foster and the octopus: her reaching out for his fingers for the first time; then, more trustingly, “riding” his hand all the way to the water’s surface. These encounters, and his description of them, were a throwback for me to one of the most magical moments I have experienced, during a 20-minute sea-bed walk in the Andamans nearly a decade ago. There were many wonders: dazzling corals, bright orange clownfish flitting in and out of their sea anemones, a motionless but vicious-looking creature that seemed entirely made up of sharp teeth, an outtake from one of HP Lovecraft’s storyboards. But the transcendental moment came when the guides gave us mashed bread to feed a big school of black-and-yellow fish that had been swimming nearby. I must have been a little late in letting go of some of the food, because as the creatures swarmed around us I felt dozens of little mouths nibbling and sucking at my fingers. For just a second or two. But nothing prepares you for the frisson that comes with an experience like this.

*****

Ultimately, though the octopus is the film’s main subject (and a fascinating one), she is also a window into a new world. The specific life lessons she “teaches” Foster can seem a little trite when looked at in isolation – I don’t think this film works best as a straight motivational treatise – but what’s important is that by the end she becomes a catalyst for his growing sense of the interconnectedness of all life.

I felt that sense during my Andamans sea-bed walk too – and I would feel it more deeply later. The trip – great fun though it was as it happened – acquired a cathartic dimension in hindsight, because just two months later I lost my Foxie. I had thought, hazily and sentimentally, about her during the walk when those fish nibbled at my fingers, and when tiny crabs shuttled past my feet into their burrows: I had thought about how, if the creatures of the deep were distant cousins to us, dogs were closer cousins still, and that my four-legged baby and I shared a common ancestor in the far reaches of time. Even now, that memory of a brief connection with a larger living world – and with an ancient biological past – brings some solace.

But back to My Octopus Teacher – it’s a stunning film, and chances are you’ll find your own epiphanies and “lessons” in it. If you watch it, try to watch it on a biggish screen.

May 16, 2021

How pop music delivers a gut-punch in Promising Young Woman

(In my Well Begun column for First Post, a shout-out for a new film I enjoyed hugely – and no, you don’t have to feel guilty about enjoying it)

------------------ Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman, one of this year’s best-picture Oscar nominees, has shiny happy music. A lot of shiny happy music. More than you’d expect in a story about an angry young woman, tormented by the rape of a friend in med-school a decade earlier, and out to get some form of revenge.

Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman, one of this year’s best-picture Oscar nominees, has shiny happy music. A lot of shiny happy music. More than you’d expect in a story about an angry young woman, tormented by the rape of a friend in med-school a decade earlier, and out to get some form of revenge.

And yet, not only is the music fun and hummable, it also somehow manages to be central to the sinuous quality of this dark, hard-to-read film.

The very first scene sets the tone. The song is Charli XCX’s catchy “Boys”, with lyrics that go “I was busy dreaming 'bout boys / Head is spinning thinking 'bout boys” – an upbeat tune that you’d associate with a party where everyone is having (innocent?) fun. The opening visuals show us some of this playing out in a nightclub, and in the first 10 or 12 shots all we see are dancing men – or, rather, fragments of dancing men. They are mostly dressed in semi-formal clothes (an after-office get-together?), swaying, drinking beer, high-fiving, slapping their own butts.

With no woman in these initial frames, for a few seconds you might think it’s a stag party or a gay bar. Whatever the case, in Covid-19 lockdown time, a scene like this carries an extra wistful charge – and I say that as someone who isn’t into big noisy parties (and definitely not into dancing at parties).

But as the main narrative begins, danger signs appear. The first words of regular dialogue we hear are “F*** her. Yeah, f*** her.”

It’s from a conversation between three men, discussing a woman colleague who has presumably complained about unequal workplace treatment. One of the guys (he seems the decent, sensitive one of the three) points out that their colleague has missed out on some client meetings since women aren’t allowed to play at the golf club. But the other two shush him up.

Then their attention is drawn to a woman sprawled out on a couch, seemingly sloshed out of her mind. New jibes follow.

“Why don’t you get some dignity, sweetheart?”

“They put themselves in danger, girls like that.”

As it happens, it is the “decent” guy – the one reluctant to badmouth his colleague, or to leer at this woman – who goes up to check on her. You might be lulled into thinking he is acting out of gallant concern and nothing else, but that illusion soon evaporates; this isn’t a film that trusts in the ability of men to be nice when they think no one’s keeping an eye on them.

It’s hard to properly discuss Promising Young Woman without providing spoilers, but I’ll keep it general. What it’s okay for you to know is that the woman in that opening scene is Cassie (Carey Mulligan) and that her mission is to seek out predators (including, or especially, men who don’t think of themselves as predatory) and give them a nasty shock.

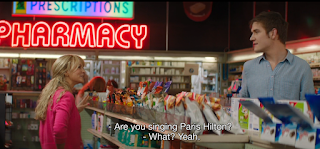

If you return to the opening scene after having watched the whole film, you’ll find much prefiguring in it, even in the very sparse dialogue: in the “f*** her” and the bullying insistence on a woman being “dignified” (often coming from people who are far from dignified themselves). By the time the sequence plays out, the memory of that cheerful opening tune, “Boys”, will have faded – to be replaced by another happy song, “It’s Raining Men”, which provides the background score for the next scene where Cassie is again on the receiving end of unwelcome male attention. Such motifs will run through the film: familiar old tunes, a few new ones. Most notably, perhaps, in the sweet scene where Cassie and a new boyfriend, unselfconsciously happy, goof around at a store where Paris Hilton’s “Stars are Blind” is playing in the background, and he starts mouthing the words to her amusement. It is the stuff of schmaltzy romantic comedy, complete with two likable people who are falling in love. But it is also preparation for a gut punch.

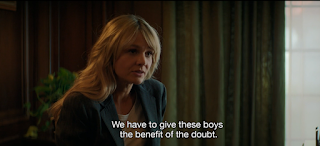

Such motifs will run through the film: familiar old tunes, a few new ones. Most notably, perhaps, in the sweet scene where Cassie and a new boyfriend, unselfconsciously happy, goof around at a store where Paris Hilton’s “Stars are Blind” is playing in the background, and he starts mouthing the words to her amusement. It is the stuff of schmaltzy romantic comedy, complete with two likable people who are falling in love. But it is also preparation for a gut punch. There are other superb musical choices, which manage to be plaintive and creepy at once – or change their effect depending on how you read or revisit a scene. One of my favourites involves the use of a lullaby sung by a little girl in Charles Laughton’s magnificent 1955 gothic thriller The Night of the Hunter (a film about two innocents up against a big bad wolf – much like Cassie feels like she has her friend Nina’s spirit accompanying her in her wanderings through the dark woods of male entitlement). But there is also another song from the 1950s, “Something Wonderful” from the musical The King and I, with lyrics that are meant to be stirring but become scary when one places them in the context of sexual assault by guys who are allowed to get away with it (because they are “achievers” in other fields, or because “we were all so young and drunk”, or “these things happen”).

There are other superb musical choices, which manage to be plaintive and creepy at once – or change their effect depending on how you read or revisit a scene. One of my favourites involves the use of a lullaby sung by a little girl in Charles Laughton’s magnificent 1955 gothic thriller The Night of the Hunter (a film about two innocents up against a big bad wolf – much like Cassie feels like she has her friend Nina’s spirit accompanying her in her wanderings through the dark woods of male entitlement). But there is also another song from the 1950s, “Something Wonderful” from the musical The King and I, with lyrics that are meant to be stirring but become scary when one places them in the context of sexual assault by guys who are allowed to get away with it (because they are “achievers” in other fields, or because “we were all so young and drunk”, or “these things happen”).

****

Promising Young Woman is among my favourites of the Oscar-nominated films (I wish it had won best actress for Mulligan, who is fabulous in a very tricky role), and that’s partly because of how it mashes tones and sub-genres, keeping a viewer thoroughly off-balance. Our experience of the film is comparable in some ways to that of the “good guy” who tries to force himself on Cassie in the opening sequence. He thinks she is barely conscious (and will presumably be unable later to remember exactly what happened) – but then she turns out to be not just sober and alert but razor-sharp, sitting up and looking him in the eye with a “What are you DOING?” In the same way that this moment represents a complete shift in gear for the man – from feeling hornily, confidently in control to stunned and scared (and perhaps even a teeny bit ashamed?) – Promising Young Woman puts its viewers through a roller-coaster of emotions. One minute you’re chuckling at what seems to be jokey banter, then a few seconds later you have been implicated in something much darker; one minute (I’m trying not to give away anything specific) you’re enjoying Cassie’s vengeance on a guy who deserves it, the next you’re afraid for her and thinking “Hey, this wasn’t supposed to play out this way.”

The irreverent or flippant tone of parts of the film, its evoking of the slasher aesthetic in places, the bright bubble-gum set design… these are things that might seem off-putting or inappropriate to a swathe of viewers: ranging from defensive men (the sort who promptly yank out #notallmen# during conversations about sexual harassment) to feminists who might wonder if the film is having a little too much fun (and encouraging viewers to have too much fun) in its telling of a very sad story. If a male writer-director had made exactly the same film – with the lilting soundtrack and the echoes of B-movies about vigilante justice – there would have been more indignant allegations about the use of a seemingly woman-sympathetic narrative as a mask to cater to the male gaze, and to construct an “entertaining” film that doesn’t even end on a properly affirmative note.