Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 16

September 18, 2021

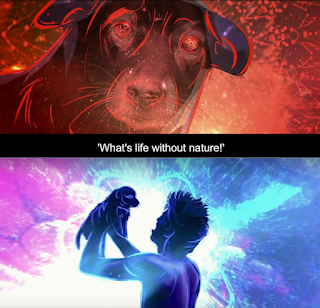

Doggone! How my ears prick up when a movie depicts an imperilled canine

(Wrote this for the Sunday Economic Times. About recent dog scenes that took me out of a film, leading to a reaction very different from the one the filmmakers would have wanted from their viewers)

-------------------------------------

In a recent podcast, discussing such weighty issues as “problematic” art or artists – and the ideological lenses we use when engaging with films or books – I articulated something I hadn’t said before on a public forum: that homosapien-centric issues – including discrimination, exploitation and other such games played by our species throughout its history – aren’t “triggers” for me in the same way that cruelty to animals is. (Or, to be more honest, cruelty to specific animals, the ones I relate with.) A few dog scenes in films watched over the past few weeks have underlined this. Take the one in Dial 100 – a conceptually promising but inert thriller – where a woman named Seema (played by Neena Gupta) enters a house at night to take another woman hostage. Seema has already got her victim to tie up the family dog Rocky (a friendly-looking Labrador), but then, irritated by his barking, she knocks him out by hitting him on the head with a vase. A little later a neighbour hears Rocky’s cries and sees him lying on the floor (still leashed, of course), blood coming out of his head. And… that’s it. Inspector Sood (Manoj Bajpayee) is thus alerted to the home invasion, but there is no further news about the dog’s fate.

A few dog scenes in films watched over the past few weeks have underlined this. Take the one in Dial 100 – a conceptually promising but inert thriller – where a woman named Seema (played by Neena Gupta) enters a house at night to take another woman hostage. Seema has already got her victim to tie up the family dog Rocky (a friendly-looking Labrador), but then, irritated by his barking, she knocks him out by hitting him on the head with a vase. A little later a neighbour hears Rocky’s cries and sees him lying on the floor (still leashed, of course), blood coming out of his head. And… that’s it. Inspector Sood (Manoj Bajpayee) is thus alerted to the home invasion, but there is no further news about the dog’s fate.

The human part of the story – the “important” part – continues, of course, but for me the scene was a deal-breaker, creating unease and revulsion. While I got that the filmmakers saw Rocky as an expendable pawn for plot movement, it was enough to set me completely against Seema. Subsequent revelations about her tragic back-story and motivations made no difference; after that scene, there was no way I was going to feel sympathy for her.

To channel the always-indignant Wokes (whom I otherwise enjoy mocking): Seema cancelled, movie cancelled.  Then there’s the scene in the short film Summer of ’92, part of the anthology series Nava Rasa, in which a troublesome dog – being chased by village youngsters – briefly falls into a swamp where most of the excreta from the village has been dumped. In the finale, in a moment guaranteed to disgust many viewers at a visceral level (while angering others who see the story’s potential caste commentary being undermined by slapstick), the faeces-covered animal enters a house and, shaking itself vigorously, covers a bunch of people – a potential bride and groom, a pandit, family elders – with human waste.

Then there’s the scene in the short film Summer of ’92, part of the anthology series Nava Rasa, in which a troublesome dog – being chased by village youngsters – briefly falls into a swamp where most of the excreta from the village has been dumped. In the finale, in a moment guaranteed to disgust many viewers at a visceral level (while angering others who see the story’s potential caste commentary being undermined by slapstick), the faeces-covered animal enters a house and, shaking itself vigorously, covers a bunch of people – a potential bride and groom, a pandit, family elders – with human waste.

Even though the dog messes things up for a likable character, this was my predominant reaction when he emerged from the slushy shit-pit: relief that the film hadn’t opted for the sort of slapstick that would involve him drowning in filth (even if the rest of the village is metaphorically swamped by bigotry). If you think it’s wrong to be more concerned about animal welfare than caste politics, steel yourself for more. A tense sequence in the hard-hitting Polish film Sweat (about a high-profile social-media “influencer” who is desolate in her personal life) has the protagonist Sylvia menaced by a man she invited into her apartment. For me Sweat was a better film than the ones mentioned above, and I definitely felt more invested in the central character – and now here she was facing a possible sexual threat from a violent man. But even so, I was just as worried about Sylvia’s little terrier, asleep on the couch on the edge of the frame. What would the man do to him if he tried to protect his human mom? Should I even continue watching?

If you think it’s wrong to be more concerned about animal welfare than caste politics, steel yourself for more. A tense sequence in the hard-hitting Polish film Sweat (about a high-profile social-media “influencer” who is desolate in her personal life) has the protagonist Sylvia menaced by a man she invited into her apartment. For me Sweat was a better film than the ones mentioned above, and I definitely felt more invested in the central character – and now here she was facing a possible sexual threat from a violent man. But even so, I was just as worried about Sylvia’s little terrier, asleep on the couch on the edge of the frame. What would the man do to him if he tried to protect his human mom? Should I even continue watching?

(Spoiler alert: it turned out to be okay to continue watching.)  There have been other, less dramatic scenes that have peeved me in smaller ways. In the recent Malayalam film Aarkkariyam, an old man, after finishing his dinner each night, goes to the gate and scrapes leftovers off his plate for the three stray dogs waiting outside. A sweet gesture, you’d think; but even here, speaking as a daily feeder of mongrels with Black-Hole-like appetites, I gaped at how tiny the morsels were, at how the dogs gulped them up in seconds and looked around hungrily for more (by which time the man had headed back, no doubt feeling like he had done a good deed).

There have been other, less dramatic scenes that have peeved me in smaller ways. In the recent Malayalam film Aarkkariyam, an old man, after finishing his dinner each night, goes to the gate and scrapes leftovers off his plate for the three stray dogs waiting outside. A sweet gesture, you’d think; but even here, speaking as a daily feeder of mongrels with Black-Hole-like appetites, I gaped at how tiny the morsels were, at how the dogs gulped them up in seconds and looked around hungrily for more (by which time the man had headed back, no doubt feeling like he had done a good deed).

In a different category are the “issue” films that use dogs for symbolic reasons, two excellent ones being Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal (2018) and Rohith VS’s Kala (2021). In both, a dog that meets a violent end becomes a catalyst for a character’s awareness of his own oppression – and subsequently a guiding spirit as well. (Think of this as a reversal of the plot arc of the 1980s cult classic Teri Meherbaniyan, in which Jackie Shroff’s death is the pretext for a dog’s discovery of selfhood.)

The lyrics of a song in Pariyerum Perumal go: “In the wilderness without you, how will I find my way? Your paw scrapes are my trail. You are not just a dog. Aren’t you me?” And Kala begins with an animated opening-credits sequence involving a dog, a foreshadowing exercise that makes complete sense – and acquires emotional force – only around halfway  through the film. There is metaphor here, but there is also a human-animal bond. I’m not exactly keen to watch a dog being blown up onscreen, or tied to train tracks, but I appreciate that these works – though primarily concerned with a human protagonist’s struggles – engage with and recognise a deep inter-species kinship.

through the film. There is metaphor here, but there is also a human-animal bond. I’m not exactly keen to watch a dog being blown up onscreen, or tied to train tracks, but I appreciate that these works – though primarily concerned with a human protagonist’s struggles – engage with and recognise a deep inter-species kinship.

All this is a way of saying that I probably won't be queuing up to watch Cruella (which, being the Cruella de Vil origin story, is possibly a part-sympathetic look at a famous puppy-slayer). But I will keep a cautious look out for more news about the Vishal Bhardwaj production Kuttey, the trailer of which strongly implies that Naseeruddin Shah, Tabu and other thespians play dogs – or is it the other way round?

[Another old post about cinematic dogs is here. And a piece about

Pariyerum Perumal is here]

September 13, 2021

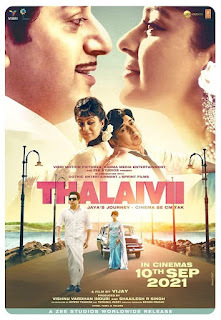

Politicians and actors: notes on Thalaivii

(Did this piece about Thalaivii for India Today. Note: I watched the Tamil version with subtitles, not the Hindi version. Think that’s important to clarify since I suspect the effect would vary quite a bit for non-Tamil speakers. Watching the film in Hindi would make suspension of disbelief more difficult, you’d tend to see Kangana playing Kangana, and become a little more conscious of the politics of casting a well-known north Indian star as a south Indian icon)

----------------- Two dramatic sequences – set 24 years apart – open the new Jayalalitha biopic Thalaivii. One of these shows the young Jaya (Kangana Ranaut) performing in the florid mode of 1960s Tamil cinema – writhing under a waterfall, jiggling her hips – and a glimpse of her soon-to-be leading man, superstar MJR (Arvind Swamy). But just before this comes a scene that is as theatrical in its own way. It is set in the Tamil Nadu legislative assembly in 1989 and depicts Jaya – new to politics – being manhandled during a scuffle between opposing parties. Whereupon she compares herself to Draupadi, with a fiery denouncement of men who don’t know how to respect women – and the implied promise of revenge.

Two dramatic sequences – set 24 years apart – open the new Jayalalitha biopic Thalaivii. One of these shows the young Jaya (Kangana Ranaut) performing in the florid mode of 1960s Tamil cinema – writhing under a waterfall, jiggling her hips – and a glimpse of her soon-to-be leading man, superstar MJR (Arvind Swamy). But just before this comes a scene that is as theatrical in its own way. It is set in the Tamil Nadu legislative assembly in 1989 and depicts Jaya – new to politics – being manhandled during a scuffle between opposing parties. Whereupon she compares herself to Draupadi, with a fiery denouncement of men who don’t know how to respect women – and the implied promise of revenge.

This could be seen as a case of showboating by a former actress (who also worked in mythological films), but another way of looking at it is that all successful politicians – even the relatively restrained or “dignified” ones – are to some degree performers: putting on a show, presenting a version of themselves for public consumption. Films about politicians or lawyers, set in parliaments or in courtrooms, have always known this well. To watch Thalaivii is to be reminded (and this is independent of the film’s quality) that political arenas are theatres, and what happens in them – especially if you have followed Indian parliamentary proceedings over the years – can be more melodramatic, more outlandish than anything in an over-the-top film.

Those opening scenes suggest Thalaivii might go on to be a film about politicians as actors, and actors as politicians – a clever, insightful look at the workings of realpolitik. Instead it settles conservatively into a depiction of Jayalalitha as pure-hearted saint, wanting to acquire power only so she can use it for a good cause. One of the film’s conceits – a pleasing but over-idealistic one – is that a woman can help clean up politics through empathy and a willingness to go to the grass roots. (“I will never like or understand politics,” Jaya says at one point, but later an epiphany hits her when she realises how cut off MJR is from the people his party is supposed to be serving – and how a caring touch is required.) This results in a manipulative, one-dimensional film, full of shots of Jaya being talked down to or pushed around – the main agenda being to create sympathy for someone who is trying to bring compassion to a callous or apathetic space.  We don’t exactly have a tradition of robust cinema built around real-life political figures. One can’t help compare Thalaivii with Mani Ratnam’s 1997 Iruvar, a fictionalised account of the friendship between MG Ramachandran and M Karunanidhi (with Aishwarya Rai as a character who marginally resembled the young Jayalalitha). A confession: I spent the more tedious bits of Thalaivii day-dreaming about Iruvar. Part of the reason why that earlier film was so effective was that by shrugging off the need for saphead verisimilitude, it could reach for more poetic truths about friendship and politics, ideology and lived experience – while also revealing something important about 20th century Tamil history and the celebrity cult. Thalaivii, on the other hand, is supposedly a straight Jayalalitha biopic, and yet, in the interests of prudence, given the statures of the real figures involved, it slightly alters character names (MGR becomes MJR) and offers sanitised depictions of events along with a highlights reel of Jayalalitha’s life, built around this basic thesis: she is underestimated and patronised – but then she hits back and Shows Them All.

We don’t exactly have a tradition of robust cinema built around real-life political figures. One can’t help compare Thalaivii with Mani Ratnam’s 1997 Iruvar, a fictionalised account of the friendship between MG Ramachandran and M Karunanidhi (with Aishwarya Rai as a character who marginally resembled the young Jayalalitha). A confession: I spent the more tedious bits of Thalaivii day-dreaming about Iruvar. Part of the reason why that earlier film was so effective was that by shrugging off the need for saphead verisimilitude, it could reach for more poetic truths about friendship and politics, ideology and lived experience – while also revealing something important about 20th century Tamil history and the celebrity cult. Thalaivii, on the other hand, is supposedly a straight Jayalalitha biopic, and yet, in the interests of prudence, given the statures of the real figures involved, it slightly alters character names (MGR becomes MJR) and offers sanitised depictions of events along with a highlights reel of Jayalalitha’s life, built around this basic thesis: she is underestimated and patronised – but then she hits back and Shows Them All.

Worse, it does this lifelessly. What’s most surprising about Thalaivii is not that it is hagiographical, but that it is so dull. Kangana Ranaut has been such a controversial figure herself in recent times, using social media as a personal kingdom for shrill, gratuitous and self-aggrandising pronouncements, even being banished from it before making a dramatic return – the way Jayalalitha did at various points during her political career – you’d think the casting alone could make for an entertaining movie that moves through multiple layers of artifice, reality and meta-references. Unfortunately that doesn’t happen. For every playful touch (e.g. the teenage Jaya reading Caesar and Cleopatra as she prepares for a tempestuous relationship with a much older, deified man), there are ten other moments where the dialogue is tiresomely on the nose. (“Now respect has come from my heart,” Jaya says out loud when she finally deigns to stands up as MJR passes her – after he has made a dubious gesture of compassion towards an injured junior artiste.)

Tell, don’t show is mostly the motto here – and the showing, when it happens, happens in slow motion. During the duller stretches, it feels like the entire film was shot in that mode, each moment milked dry for emotional effect. Ironically, by presenting her only as someone who is constantly condescended to (“This is not a cinema shoot, why are you here?” Karunanidhi asks her when she comes to see MJR in hospital), and must goad herself to new heights in response, the film itself diminishes and makes her one-note.

P.S. I thought there were a couple of subtle Iruvar tributes – as in the staging of a scene where Karunanidhi feels slighted when an audience listening to his speech turns its attentions to MGR. And in the casting of Nassar as Karuna (he played the Annadurai figure in Iruvar).

September 4, 2021

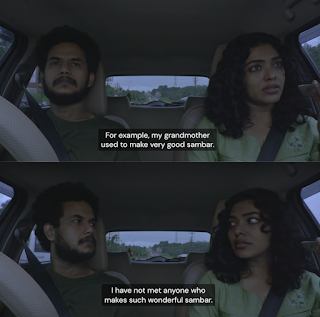

On Don Palathara’s Joyful Mystery: an arguing couple, a fixed camera and an 82-minute take

(One of my most pleasing recent discoveries is the cinema of Don Palathara [whose work can be found on Mubi India, for anyone interested]. I have watched three of his five films so far, most recently Everything is Cinema, which I loved for its cold, self-absorbed misanthropy and for the texture of Palathara's voiceover, which dominates much of the film. For now, though, here’s a piece I did for Money Control about Santhoshathinte Onnam Rahasyam)

(One of my most pleasing recent discoveries is the cinema of Don Palathara [whose work can be found on Mubi India, for anyone interested]. I have watched three of his five films so far, most recently Everything is Cinema, which I loved for its cold, self-absorbed misanthropy and for the texture of Palathara's voiceover, which dominates much of the film. For now, though, here’s a piece I did for Money Control about Santhoshathinte Onnam Rahasyam)-----------------------------------------

A tiny moment – lasting barely a couple of seconds – in the new Malayalam film Santhoshathinte Onnam Rahasyam (English title: Joyful Mystery) drew a surprised chuckle out of me. Maria and Jithin – an unmarried couple, not too secure financially, trying to get their careers on track – are on their way back from a clinic. They are facing the possibility that Maria is pregnant (the test result will come later in the day) and are trying to process what this might mean for their future, and what their options are – abortion included. For much of the drive to the clinic they have been arguing, exchanging recriminations or being passive-aggressive in the way couples often are in these situations. The air is thick with tension.

Then something shifts, if only momentarily. Maria – a tabloid journalist – is on a phone interview with a movie director who is pontificating on about his work. Even as he claims to be making “the first feminist Malayalam film by a man”, he decrees that there are some things only women should do since they excel at them. Such as making sambhar. What if my grandmother had become a revenue officer, he asks rhetorically. The whole family would have missed out on her amazing sambhar! As the director says these words (we can hear his voice on Maria’s speaker-phone), there is a split-second exchange of bemused glances between Maria and Jithin. It’s deadpan, not underlined, but very effective and funny.

Then something shifts, if only momentarily. Maria – a tabloid journalist – is on a phone interview with a movie director who is pontificating on about his work. Even as he claims to be making “the first feminist Malayalam film by a man”, he decrees that there are some things only women should do since they excel at them. Such as making sambhar. What if my grandmother had become a revenue officer, he asks rhetorically. The whole family would have missed out on her amazing sambhar! As the director says these words (we can hear his voice on Maria’s speaker-phone), there is a split-second exchange of bemused glances between Maria and Jithin. It’s deadpan, not underlined, but very effective and funny.Another amusing interlude: shortly before this scene, they gave a ride to an elderly woman who revealed that she was at a wedding attended by a hundred people – much to the consternation of Jithin, already displeased about sharing an enclosed space with a stranger in Covid-19 time. After the woman gets off at her destination, he exclaims, “She had primary contact with 100 people.” Maria looks pensively at the departing woman.

In the lead-up to both these moments, Maria and Jithin had been in sullen-silence mode – but now we see them bonding, however briefly. They get to step back from their fraught situation for a moment and become one “unit” again – a couple who is sufficiently attuned to each other (and have enough in common as broadly liberal young people) that they can share a wordless glance at the idiosyncrasies, irresponsible behaviour or posturing of others.

Both these scenes are in the second half of the film, and after all the angry, accusatory talk in the first half this represents the beginning of a return to some order, the calm after the storm. Which is not to say that the film is headed for a conventionally happy ending, or that the couple’s struggles are going to be over soon. But something vital about the relationship has been captured, adding warmth and plausibility to the narrative.

*****

Much of the talk around this film, written and directed by Don Palathara, will understandably focus on the formal device at its centre: it is filmed in a single take that runs more than 80 minutes, with one fixed camera at the front of the car in which Maria (played by Rima Kallingal) and Jithin (Jithin Punthenchery) are travelling.

This means that almost throughout, we watch them up close as they talk or negotiate uncomfortable silences. With a couple of breathers here and there: Jithin stopping the car and getting out to bring Maria a lemon for her nausea, or to smoke for a while after an argument; Maria leaving the car for a few minutes when they reach the clinic.

There are bursts of conversation, explosions of anger, mood swings. And a few long pauses that are always risky in a film like this since all the viewer can do during these periods is to look at the two people on the screen, conjecture what they might be feeling or thinking. Watch Jithin keeping his emotions (mostly) under control and his eyes on the road, making a determined effort to be the Sensitive Male but with his mind probably ticking away under that composed exterior; look at Maria, more agitated and demonstrative, dealing with her current nausea as well as the possible bodily changes to come, worrying about career and societal judgement, frustrated that the man next to her can afford to be so unruffled since he isn’t as directly affected.

There are bursts of conversation, explosions of anger, mood swings. And a few long pauses that are always risky in a film like this since all the viewer can do during these periods is to look at the two people on the screen, conjecture what they might be feeling or thinking. Watch Jithin keeping his emotions (mostly) under control and his eyes on the road, making a determined effort to be the Sensitive Male but with his mind probably ticking away under that composed exterior; look at Maria, more agitated and demonstrative, dealing with her current nausea as well as the possible bodily changes to come, worrying about career and societal judgement, frustrated that the man next to her can afford to be so unruffled since he isn’t as directly affected. With most of the famous lengthy takes in film history (in classics like Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons and Touch of Evil, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope and Under Capricorn, or in modern films like Birdman or Russian Ark or 1917), the camera moves with the characters. A twelve-minute-long establishing shot in another recent Malayalam film, Malik, takes us through a large house, up and down stairs, into different rooms, as we meet some of the film’s protagonists.

The single take in Santhoshathinte Onnam Rahasyam is very different from these. On the face of it, the unblinking and unmoving camera makes this film less “cinematic”, more stationary and theatre-like. But the technique works very well visually for the situation. During the driving scenes, Maria and Jithin are in fixed positions in the car, literally strapped in, while the scenery behind them changes subtly: the buildings, the greenery, the shifts in light as they pass under a canopy. They are in a private space – with each of them leaving it occasionally but soon returning – while other things orbit around them. People enter and exit (mostly as voices on a phone), there are conversations – with family, friends – that in subtle ways touch on the subject of what is conventional or unconventional, socially approved or frowned upon, and on aspects of the parent-child relationship; things that are relevant to Maria and Jithin’s current circumstances.

It’s one thing to say that a particular film is for a “patient viewer” – that’s a given in a case like this – but so much here hinges on the performances of the two leads; with the camera scrutinising them so closely, the slightest inadequacy or implausibility would make the whole film lose its moorings. Jithin Punthenchery and Rima Kallingal – who are constantly required to walk a tightrope between the mundane and the dramatic, between improvisation and a scripted narrative – are excellent throughout. Even when there is nothing particularly exciting or novel happening in the conversation, when the whole point of it is its banality, they kept me gripped.

It’s one thing to say that a particular film is for a “patient viewer” – that’s a given in a case like this – but so much here hinges on the performances of the two leads; with the camera scrutinising them so closely, the slightest inadequacy or implausibility would make the whole film lose its moorings. Jithin Punthenchery and Rima Kallingal – who are constantly required to walk a tightrope between the mundane and the dramatic, between improvisation and a scripted narrative – are excellent throughout. Even when there is nothing particularly exciting or novel happening in the conversation, when the whole point of it is its banality, they kept me gripped. Looked at in one way, this film’s structure is very simple: take a potentially dramatic development and use it to examine the quotidian workings of a relationship over the course of a long car drive. End with a measure of calm having been reached, even a little smile here and there, an affectionate touch. Some might even call it simplistic. But if you accept its slice-of-life approach on its own terms, and also see it as a work that is self-aware about the limitations of this kind of “experimental” cinema (there is a nod to this in the conversation with the pretentious director, who is voiced by Palathara himself), the staging and the performances add up to a lot. This is an absorbing view of how close relationships work; how two people, caught in a particular moment, interact with each other and with the world.

September 3, 2021

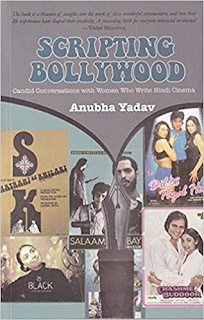

Screenplays and petticoats: a book about Hindi cinema's women screenwriters

(Along with the Green Knight review [in the previous post], this is the other short piece I have in this week’s India Today – a review of Anubha Yadav’s very engrossing Scripting Bollywood: Candid Conversations with Women Who Write Hindi Cinema)

(Along with the Green Knight review [in the previous post], this is the other short piece I have in this week’s India Today – a review of Anubha Yadav’s very engrossing Scripting Bollywood: Candid Conversations with Women Who Write Hindi Cinema)Juhi Chaturvedi says she reads dialogues out loud while writing them: “My staff sometimes comes to my room to check if everything is fine.” Shama Zaidi reads big novels non-linearly – “I decide how much I want to read and I read in stages” – and believes a web-series can be experienced the same way. Sooni Taraporevala decided to direct the film of her script Little Zizou because she wanted to maintain its quirkiness. Screenplay structure is like a petticoat, says Shibani Bathija – without it, “you will not get the form you need. The sari will fall right off”. The late Kalpana Lajmi says she finds depictions of romance in the films of Gulzar and Shyam Benegal dry, and that “there is more ras in a woman’s gaze”.

Little details like these – observations, back-stories, personal whimsies – provide the beating heart of this collection of interviews with 14 woman screenwriters. They give Scripting Bollywood the same free-flowing, unpredictable quality that Taraporevala wanted her film to have.  This book is a response to two levels of “invisibilising”: the neglect of, or glossing over of, a writer’s contribution to filmmaking; and the more specific neglect of female writers over the decades. The subjects include veterans like Zaidi and Sai Paranjpye as well as younger writers like Chaturvedi and Devika Bhagat who work in the exciting new worlds of the indie film and the web-series. This means that all sorts of cinematic idioms are contained here: from “parallel” to “commercial”, from overtly progressive films to the ones that get labelled “problematic” because of their politics. And the stories, personalities and viewpoints are equally varied.

This book is a response to two levels of “invisibilising”: the neglect of, or glossing over of, a writer’s contribution to filmmaking; and the more specific neglect of female writers over the decades. The subjects include veterans like Zaidi and Sai Paranjpye as well as younger writers like Chaturvedi and Devika Bhagat who work in the exciting new worlds of the indie film and the web-series. This means that all sorts of cinematic idioms are contained here: from “parallel” to “commercial”, from overtly progressive films to the ones that get labelled “problematic” because of their politics. And the stories, personalities and viewpoints are equally varied.

Yadav invisibilises herself in a sense by presenting the conversations in the “as told to” format – we get only the voices of the subjects, which creates a hushed, intimate, stream-of-consciousness effect. Some writers speak a little more about craft or routines, others focus on formative experiences or influences. Rapports with directors – Urmi Juvekar’s work with Dibakar Banerjee, for instance, or Honey Irani’s with Yash Chopra or Bathija’s with Karan Johar – are discussed in terms of conflict or cooperation. Some see being a woman as central to their experience, others appear not to give it much importance. There are different perspectives on the female gaze in scriptwriting, and insights into the challenges of various periods in film history: here is Kamna Chandra relating how she wrote Prem Rog for Raj Kapoor, who made some changes “to suit a more mainstream film”; and here is Chandra’s daughter Tanuja, decades later, writing in the multiplex era or for independent American producers.

Importantly, before moving on to the main interviews, Yadav provides context about some of the women who played key roles – as producers, directors, writers, or sometimes all at the same time – in the early years of the talking Hindi film: figures like Fatma Begum, Ratan Bai and Jaddan Bai, whose contribution to screenwriting has barely been noted in the historical record. This is also a reminder of the value of the present book – and, hopefully, others that will follow it – as a chronicle of cinema’s undervalued creators.

The Green Knight – a short review of a lovely-looking film (watched in a movie hall!)

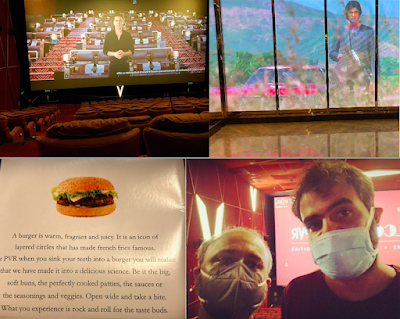

(I have a couple of short pieces in this week’s India Today. The first is this brief review of the new film The Green Knight. At the bottom of the post you can see a few images from a rare visit to a movie hall – the revamped PVR Priya, where the preview screening was held. I was there with Uday Bhatia, and apart from the film we got to experience a burger described as “an icon of layered circles that has made french fries famous”)

In one important sense, David Lowery’s The Green Knight is an easy film to watch: it is a beautiful sensory experience, especially if you’re brave enough to go to the theatre for it. The stately compositions and art design, the beautiful Irish settings (complemented by some computer-generated imagery that one might feel ambivalent about), the mesmerizingly dark, hushed tone – all this adds up to a sweeping canvas that never loses its intimacy. But in narrative terms, this medieval fantasy is determined not to make it easy for a viewer, even one who is broadly familiar with the Arthurian legends. For instance: early on, you’ll see King Arthur, Queen Guinevere, the Round Table, the sword Excalibur and even Merlin the wizard, but the film doesn’t underline who they are or try to give the viewer an “Aha!” moment. Also, if you have been mollycoddled by OTT films and series during the pandemic, consider yourself warned: here be no subtitles. You might feel the need for those, given some of the dense accents and even the rune-like chapter heads that appear on the screen.

But in narrative terms, this medieval fantasy is determined not to make it easy for a viewer, even one who is broadly familiar with the Arthurian legends. For instance: early on, you’ll see King Arthur, Queen Guinevere, the Round Table, the sword Excalibur and even Merlin the wizard, but the film doesn’t underline who they are or try to give the viewer an “Aha!” moment. Also, if you have been mollycoddled by OTT films and series during the pandemic, consider yourself warned: here be no subtitles. You might feel the need for those, given some of the dense accents and even the rune-like chapter heads that appear on the screen.

Adapted from the 14th century Chivalric poem “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (which you might want to quickly look up beforehand), this is the story of Arthur’s nephew Gawain (Dev Patel) and his fateful encounter with the mysterious, magical Green Knight. A game of “exchanges” requires that after Gawain has beheaded this tree-like being, the latter will return the favour a year hence. Thus begins a version of the Hero’s Journey, with Gawain setting out to meet his nemesis and having a string of strange encounters along the way – including one with the ghost of Saint Winifred, and another with a red fox that might appear sweet until you realise it is CGI.

Without giving away spoilers, The Green Knight builds to a very moving climax that might remind some viewers of The Last Temptation of Christ (the book and the film), or some of the stories about “maya” (illusion) in Hindu mythology. By the time Gawain asks someone “Are you certain the Green Chapel is that close?” late in the narrative, we can tell that the Green Knight waiting in his “chapel” is a symbol for the protagonist’s personal arc. Does he choose a dramatic destiny or a safe one, and is it really possible to make such a choice? Or as another character puts it, “Why greatness? Is goodness not enough?”

But looked at from another perspective, those are very limited, human-centric themes. Given the altered Covid-19 world we live in, The Green Knight also feels like it is about something much bigger: our relationship with nature and our destruction of the ecological balance; about the “greenness” that we try to bend to our own puny wills. If you hack away at a green knight’s limbs, will it pay you back manifold? We are all learning the answer to that question now.

Regardless of how you interpret its meaning, this is a haunting film that rewards more than one viewing – as long as you don’t go into it expected a fast-paced, action-filled adventure.

----------------------------------------------------

Pics from a PVR Priya expedition with Uday Bhatia:

August 31, 2021

A response to the Spectator article about Pen Farthing's animals

This is a limited, very personal part-response to this Spectator piece expressing anguish about the evacuation of Pen Farthing’s animals from Afghanistan, and calling it a “moral abomination”. (I wrote a bit about Farthing's books here.) As often happens in these cases I’m caught between feeling sympathy for the basic concerns expressed in the piece while also being aghast at how the whole thing is founded on the comfortable certitude that animals are innately less important than humans; that they can’t be sentient in the way that we are; that we don’t have a huge responsibility towards them, especially during catastrophes manufactured by our species.

I’m cynical enough to know that this is a pointless exercise (apart from helping me articulate some of my feelings), that nothing I say here will make a whit of a difference to anyone who hasn't had the firsthand experience of seeing how “human” — or more than “human” — an animal can be. But here goes anyway, picking on a few specific things.

About this:

“…a perfect example of esoteric domestic western priorities being put ahead of the people we were supposedly there to help, the sort of behaviour that dooms our efforts overseas and alienates the rest of the world.”

“Esoteric domestic western priorities”? Recognising that non-human animals are capable of the same degrees of suffering that humans are, that they can have comparable emotional lives — and that in a world chockful of human-constructed disasters and conflicts, we might have as big a responsibility to living, feeling creatures that have been domesticated and made dependent on us as we do to our own species: that’s an “esoteric priority”? Politely, no. And it shouldn't be.

I also find the conflating of this with “Western/First World” — and the implication that this is all about privileged/bored people and their prioritising of “cute puppies” over suffering humans — very condescending and strange. Especially since I am involved with “esoteric” pursuits every day in the context of street dogs and the conversations/arguments around them in India; conversations that most “developed” Western countries wouldn’t even be having since they have zero tolerance for such animals.

About this:

“Consider that many Muslims consider dogs to be impure. Now imagine how it must look for us to airlift them out ahead of our human allies.”

IF that first sentence is true in some sweeping, general sense, maybe the problem lies with the people who hold the view. In an ideal world (definitely not in this one), it might be amended at some point with the aid of some education, including emotional education. (Though plenty of non-Muslim anthropocentric “liberals” are in need of this emotional education too, as one can tell from the worthies who have been endorsing the Spectator article.)

If I were to make a statement like “My belief system considers Muslims to be impure” or “…women to be impure” or “…Dalits to be impure” (or insert whatever other human group you like), I would understandably be cancelled for all time (at least by the members of any circles I might want to belong to). But when faced with the possibility that a culture or religion considers *dogs* to be impure or beneath contempt (and the horrible consequences of this in countries like Afghanistan have been well-chronicled), we are expected to be mindful of it (or completely kowtow to it) in the interests of tolerance or cultural sensitivity. Or, well, realpolitik. The piece certainly carries the implication that we should respectfully tiptoe around such “beliefs”.

(Amusingly, that paragraph begins with the line “Even setting morality to one side…” and in my view that’s what the writer ends up doing by the end of the para — though he almost certainly didn’t intend it to be read that way.)

About this:

“…as one interpreter asked me a few days ago, why is my five-year-old worth less than your dog… I didn’t have an answer. What would your answer be?”

Not that anyone asked me, but my answer would be: not worth less, worth *the same* as my dog-child. (Privately I have always felt that my maternal love for Foxie and later for Lara has been deeper and more involved than the love that many fathers of human children — mine included — feel for their offspring; but that kind of judgement has no place in a piece like this.) What we have in Afghanistan — and in many other places at various times in history — is a horrible situation where it’s a given that some people (through a combination of influence, position, circumstance, contacts and of course sheer luck) will get away relatively unscathed while others won’t. Let’s hypothesise that non-human animals weren’t part of this equation at all — that only humans were involved at every level. In that case, we would STILL have multiple situations where the parent of one five-year-old human child would be able to ask the parent of another five-year-old human child: “Why is your child worth more than mine?” There's something — I'll just use the word "mischievous" while I think of a better word — about framing the question in the particular way that Ashworth-Hayes does in his piece.

Without going on nitpicking about other things in the piece, here’s a bit that caught my eye as I was skimming over it again:

“I don’t particularly blame Pen. I’d probably want to get my pets out of a warzone too.”

“Probably”. That tells me everything I need to know about Sam Ashworth-Hayes’s understanding of what a human-animal relationship can be. I hope he doesn’t actually have any pets of his own, or that if he does have any — as status symbols or house decor or whatever — they are being looked after by someone who is better equipped to do it. Anyway, it’s obvious that the Spectator piece and the approving conversations around it are for people who have never been able to see the worth and individuality of animals (outside of their usefulness on a plate).

P.S. one last thing — I actually agree with the first sentence of the Spectator piece. There are no genuinely meaningful "feel-good" stories from Afghanistan at the moment; in the sense that every such tale of rescue is offset by a dozen other tragedies (for all sorts of creatures). Even we tunnel-visioned animal-rights activists know that.

August 30, 2021

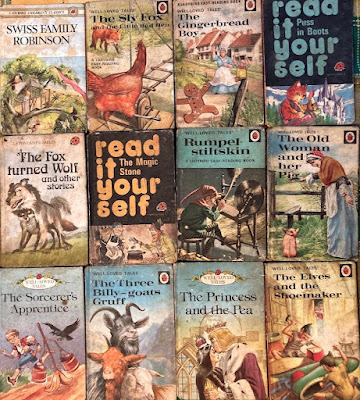

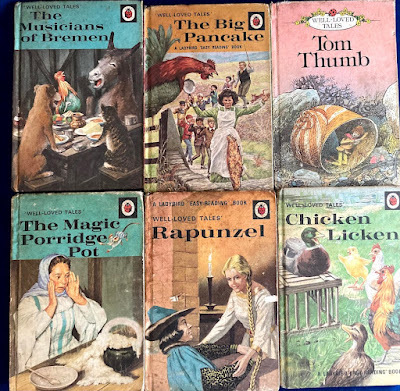

My old Ladybird books (and a magic stone soup, or a story about stories)

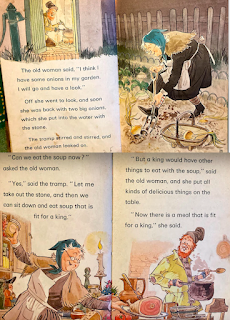

From the nostalgia pages: these are a few of the dozens of Ladybird books I have – among the earliest books in my life. By the time I was four I could manage “Reading Level 5”, though many of the cultural references or colloquialisms were well beyond my grasp – sometimes I got a vague sense of what certain things were intended to be (“gingerbread man”, “billy goats gruff”) without fully understanding or relating to them. (A couple of years later, this would happen again when I read about the “scones”, “eclairs” or “potted meat” consumed by the Famous Five at their picnics.) A few days ago I took out these Ladybirds and, flipping through them, found that I vividly recalled many of the images and even some of the specific phrases and conversations – though I was seeing them for the first time in nearly 40 years. How strange the human mind is, especially our dormant/long-term memory.

From the nostalgia pages: these are a few of the dozens of Ladybird books I have – among the earliest books in my life. By the time I was four I could manage “Reading Level 5”, though many of the cultural references or colloquialisms were well beyond my grasp – sometimes I got a vague sense of what certain things were intended to be (“gingerbread man”, “billy goats gruff”) without fully understanding or relating to them. (A couple of years later, this would happen again when I read about the “scones”, “eclairs” or “potted meat” consumed by the Famous Five at their picnics.) A few days ago I took out these Ladybirds and, flipping through them, found that I vividly recalled many of the images and even some of the specific phrases and conversations – though I was seeing them for the first time in nearly 40 years. How strange the human mind is, especially our dormant/long-term memory.

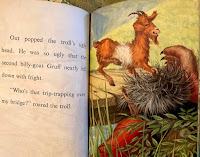

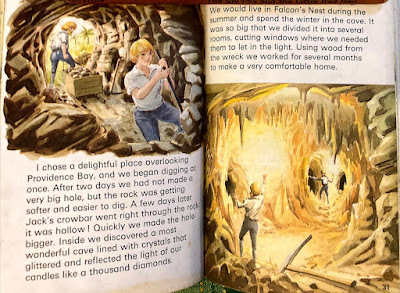

Some of the pictures here: the creepy (pre-internet) troll coming out from under his bridge to terrify passing goats; the building of the cosy winter’s cave in Swiss Family Robinson (an image I always loved for

Some of the pictures here: the creepy (pre-internet) troll coming out from under his bridge to terrify passing goats; the building of the cosy winter’s cave in Swiss Family Robinson (an image I always loved for

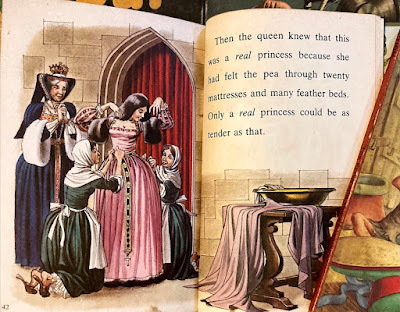

the sense of warmth and security it provided to go with the family’s adventures); the enormous stack of mattresses on which a young woman is required to sleep to prove she is a “real princess” because she is delicate enough to be bruised by the pea far below (not the most politically correct of stories, of course, and it strikes me now that around the time I read this book Princess Di was being expected to undergo a virginity test before her wedding to Charles – in that weird faraway land we call the Real World).

the sense of warmth and security it provided to go with the family’s adventures); the enormous stack of mattresses on which a young woman is required to sleep to prove she is a “real princess” because she is delicate enough to be bruised by the pea far below (not the most politically correct of stories, of course, and it strikes me now that around the time I read this book Princess Di was being expected to undergo a virginity test before her wedding to Charles – in that weird faraway land we call the Real World).

I remember the swell of pride when I learnt the meanings of words like “apprentice” (from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) or “cauldron” or “tapestries” or “parsley”, or learnt how to pronounce complicated names like Rumpelstiltskin. Looking again at the drawings in the Rapunzel book, I remember wondering if her hair really was longer than my mother’s.

I remember the swell of pride when I learnt the meanings of words like “apprentice” (from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) or “cauldron” or “tapestries” or “parsley”, or learnt how to pronounce complicated names like Rumpelstiltskin. Looking again at the drawings in the Rapunzel book, I remember wondering if her hair really was longer than my mother’s.

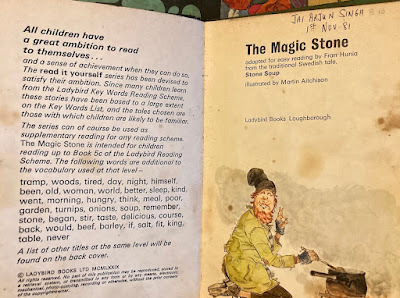

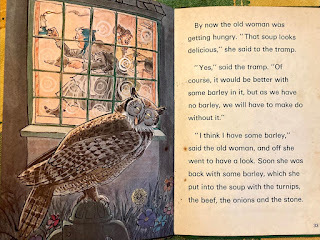

And then there is The Magic Stone, a story I was fascinated by at the time, and which (unlike most of the other titles here) has never been very far from my mind. Perhaps because I think of it as a fable about the nature of storytelling. Here is what happens: a tramp seeks shelter for the night in an old woman’s house. She claims she is poor and has no food for him, but he sees that she has a well-tended garden and a well-stocked kitchen. He offers to make them a delicious magic soup with just a pot of boiling water and a single stone taken from her garden. As he stirs the “soup”, he tastes it, pronounces it excellent but casually adds that it would be even better with a bit of onion – then a pinch of salt, then some turnips, and so on; the woman, increasingly excited by this display, rushes off to get those things as he mentions them. Until what they have is a full-fledged broth made up of delicious ingredients from her garden and kitchen. (Plus one stone, essential and redundant at the same time.)

And then there is The Magic Stone, a story I was fascinated by at the time, and which (unlike most of the other titles here) has never been very far from my mind. Perhaps because I think of it as a fable about the nature of storytelling. Here is what happens: a tramp seeks shelter for the night in an old woman’s house. She claims she is poor and has no food for him, but he sees that she has a well-tended garden and a well-stocked kitchen. He offers to make them a delicious magic soup with just a pot of boiling water and a single stone taken from her garden. As he stirs the “soup”, he tastes it, pronounces it excellent but casually adds that it would be even better with a bit of onion – then a pinch of salt, then some turnips, and so on; the woman, increasingly excited by this display, rushes off to get those things as he mentions them. Until what they have is a full-fledged broth made up of delicious ingredients from her garden and kitchen. (Plus one stone, essential and redundant at the same time.)

I loved the way this story, though repetitive or circular in its structure, grew and grew, like the soup itself; an ingredient here, a layer there. And how the illustrations too became more colourful and elaborate as the “menu” expanded from a single round stone to the full table “fit for a king” that the old woman sets out in gratitude. I was a year or two away from my encounters with Indian mythology – including the tales from the Mahabharata and the Puranas that have grown and shape-shifted through oral retellings over the centuries – but I think the fable of the stone soup gave me an early insight (even if I couldn’t have articulated it back then) into how a story may be constructed over time so that it is constantly a work in progress, never “final”. And how, even when a story *does* have a clear ending, an enthusiastic reader is free to keep taking it in new directions.

I loved the way this story, though repetitive or circular in its structure, grew and grew, like the soup itself; an ingredient here, a layer there. And how the illustrations too became more colourful and elaborate as the “menu” expanded from a single round stone to the full table “fit for a king” that the old woman sets out in gratitude. I was a year or two away from my encounters with Indian mythology – including the tales from the Mahabharata and the Puranas that have grown and shape-shifted through oral retellings over the centuries – but I think the fable of the stone soup gave me an early insight (even if I couldn’t have articulated it back then) into how a story may be constructed over time so that it is constantly a work in progress, never “final”. And how, even when a story *does* have a clear ending, an enthusiastic reader is free to keep taking it in new directions.

August 22, 2021

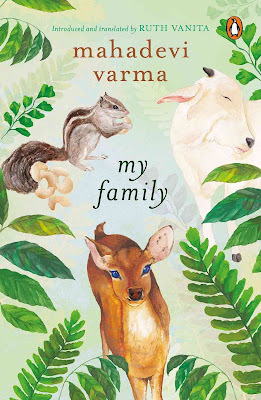

"No one perceived the beauty with which my heart had become acquainted" - on Mahadevi Varma and her non-human family

(It's been a while since I did a longish review-essay for Scroll, but I was very taken by this translation of Mahadevi Varma’s 1972 book Mera Parivar – a collection of pieces which suggest that her growing attentiveness to the world of animals and birds was central to her development as a writer. Here’s the piece) Reading the lovely new book My Family – a collection of short pieces by the celebrated Hindi poet Mahadevi Varma about the animals and birds in her life, originally published as Mera Parivar in 1972 – two early passages leapt out at me. Taken together, they are indictments of how often and how easily the bond between humans and non-humans is underestimated or glossed over.

Reading the lovely new book My Family – a collection of short pieces by the celebrated Hindi poet Mahadevi Varma about the animals and birds in her life, originally published as Mera Parivar in 1972 – two early passages leapt out at me. Taken together, they are indictments of how often and how easily the bond between humans and non-humans is underestimated or glossed over.

The first is from the introductory note by the translator, writer-academic Ruth Vanita. Some of Mahadevi’s biographers and critics, Vanita tells us, barely acknowledged Mera Parivar in their studies of her life and work. Even as they tried to understand Mahadevi through her other writings, or offered psychological profiles of her as a repressed or unfulfilled woman “longing for companionship” (presumably because she remained unmarried and lived in a hermitage-like environment for most of her life), they didn’t attach much importance to her relationships with non-human creatures.

And yet here is Mahadevi Varma herself, in her “Atmika” (preface), describing – with intensity and precision – a life-changing moment she had as a child, when she rescued a little chick that was destined to be cooked for dinner. She writes of her initial inability to understand why the chick had been taken away, the anguished helplessness she felt when she realised its intended fate and thought it was too late to save it. (I was reminded of Patricia Highsmith’s “The Terrapin” – one of many great stories about the innate concern that many children feel for other life forms – about an animal that couldn’t be saved from a cooking pot, and how a little boy is scarred as a result.) Most tellingly, Mahadevi explains how this incident led her to note down identifying marks for the animals and birds she knew and cared about. It’s as if she felt a moral duty to imprint their distinct features and personalities on her mind’s eye. “I had no other way to prove that I was their protector.”

Here, then, are the building blocks of a writing life: learning to observe, record and articulate. As Vanita puts it in her Introduction, “Mahadevi’s acclaimed portraits of humans, whether villagers, vendors, domestic workers or fellow writers, develop from her first recording of a non-human fellow being’s individuality.”

Despite Mahadevi’s immense stature in twentieth-century Hindi literature, and despite the importance that she herself attached to her inter-species relationships, this translation marks the first time that Mera Parivar is available in English – another reminder of its neglect. And a travesty, because every page of My Family is evidence of the centrality of the animal world not just to her daily life but to her artistic development.

*****

A cliché goes that art expresses the human condition, that the best of it is rooted in humanism, broadly defined as the transcending of the many divides, the many forms of “othering”, that cause conflict in the human world – class, gender, religion, race, caste. What doesn’t get acknowledged enough in these conversations is that such prejudice and discrimination can be extended to our collective treatment of other species; empathy for “others” can equally apply – both in the interests of our humanity and in the broader interests of the ecology and environment – to the non-human world.

Creative people have addressed this in many ways – such as through the anthropomorphising of animals in literature, painting and other arts. One can understand and respect this approach while also recognising its limitations. When done well, in children’s literature for instance, it can help in the early sensitising of children to the possible inner lives of other species; but there are pitfalls attached, such as a child’s disappointment when a real-world animal turns out not to be “smart” or “entertaining” in the way that we humans define those concepts.

Either way, one can keep looking closely at animals, noting the markers of sentience and personality (things that usually leap out at you once you make an honest and concentrated effort), recognising the ways in which their behaviours can be similar to ours in some ways and very different in others. Forming relationships with them. This is something Mahadevi began doing early in her childhood, but it also became a lifelong endeavour, each new experience embellishing and adding new meaning to the ones that had come before it.

There are only seven chapters in the main body of My Family, each a pen-portrait of a specific animal or bird (except for the last chapter, which is about three creatures who played an important role in the author’s formative years). Once you have finished reading the book, you might well feel that Mahadevi could have easily written another dozen such pieces about her non-human companions. And yet, what is contained in these page is a universe of detail and observation, in fluid prose that is full of humour and warmth.

Here is a peacock named Neelkanth picking up baby rabbits by one ear with his beak (“He would often sit down in the dust with his wings spread out, and they all would play catch-as-catch-can in his long tail and thick wings”) while also being hassled by the competing affections of the peahens Radha and Kubja. And here is the baby mongoose Nikki of Mahadevi’s childhood, described as “an anarchist like us” – much like little Mahadevi and her siblings, Nikki had sneaked away from his parents in the afternoon to seek new adventures. (When Mahadevi’s mother orders her to return him to his parents’ burrow, she feels deep sympathy for the little creature. “If our father were to make us sit in front of him in a small room night and day and keep teaching us, while our mother sat nearby stitching and knitting, how would we feel?”)

There are clear-eyed, unsentimental views of the random violence inherent in the natural world: a cat finding its way into a burrow and tearing to pieces a family of rabbits; a much-loved Himalayan dog being killed by a hyena while out running errands for villagers; the cruelty of a cow being fed a needle by an envious milkman; a bad-tempered rabbit named Durmukh showing a version of toxic masculinity by attacking his own wife and children. And there are poignant descriptions of more natural deaths, such as that of the squirrel Gillu who holds on to Mahadevi’s hands on the last night of his life.

Amidst the conflict, there is beauty and tenderness. A dog named Neelu gently holds fledglings in his mouth until they are brought to safety. The peacock may be a “martial vehicle” – the steed of the war-loving god Karthikeya – but he is also, through his dancing, a practitioner of art and grace. In one of the philosophical asides scattered through the book, Mahadevi contemplates that if humans communicated only with their eyes, many arguments would come to a quick end. “Perhaps it is because of this that one’s spirit, wounded by human voices attacking one another and by the burden of meaningful words, longs to be healed and consoled by the sandal paste of these wordless beings’ fluid, affectionate gaze.” Of the languorous movements of a cow named Gaura, she writes, “There is beauty in speed, but not as much beauty as in a slow pace. The speed of an arrow can dazzle the eyes for a moment, but a flower’s slow, circular movement in a gentle breeze is a feast for the eyes.”

Here and elsewhere, it is easy to see what she means when she says that “all my memoirs have sprouted, budded and bloomed from this childhood prose expression”. The elegance of Vanita’s translation notwithstanding, many passages made me yearn to read the Hindi original. (A description of the lustrously white Gaura with her red calf – evoking snow and fire – was originally, as Vanita tells us: “Mata-putra donon nikat rehne par himrashi aur jalte angaarey ka smaran karate thay.”)

**** As someone who has developed a close interest in other life-forms while living in a harsher, less animal-friendly urban environment than Mahadevi did, reading My Family was a source of both envy and fascination for me. My limited interactions with animals in recent years, though centred on a confounding variety of street dogs, has occasionally extended to monkeys, peahens, crows and squirrels. (And rats, which can be very personable creatures. When I take a freshly trapped rat to a nearby park and let it out, I now look for the particular way in which it leaps out of the opened trap, whether it scuttles off in a blind panic without trying to take stock of its new environment, or whether it pauses for a bit, looks around contemplatively – there I go “anthropomorphising” – and then picks the wisest exit strategy.) Mahadevi’s pieces felt like motivation to observe even more closely, within the constraints of my environment.

As someone who has developed a close interest in other life-forms while living in a harsher, less animal-friendly urban environment than Mahadevi did, reading My Family was a source of both envy and fascination for me. My limited interactions with animals in recent years, though centred on a confounding variety of street dogs, has occasionally extended to monkeys, peahens, crows and squirrels. (And rats, which can be very personable creatures. When I take a freshly trapped rat to a nearby park and let it out, I now look for the particular way in which it leaps out of the opened trap, whether it scuttles off in a blind panic without trying to take stock of its new environment, or whether it pauses for a bit, looks around contemplatively – there I go “anthropomorphising” – and then picks the wisest exit strategy.) Mahadevi’s pieces felt like motivation to observe even more closely, within the constraints of my environment.

Reading this book, I was also reminded of the title of a 2008 essay by Vandana Singh, “The Creatures We Don’t See: Thoughts on the Animal Other.” Singh writes:

“It seemed as though humans were so intensely obsessed with their own concerns that they didn’t ‘see’ other life-forms, let alone recognize their significance […] Just as being blind to the oppression of women creates conditions where this oppression continues unchecked, being unable to ‘see’ other creatures allows us to go about blindly and stupidly destroying the ecosystems on which we depend...To not recognise the connection between us and other species is to suffer from a sort of mass autism.”

In this light it is telling that many of Mahadevi’s biographers and critics failed to “see” the creatures she wrote about, or the attentiveness with which she wrote about them.

As Ruth Vanita notes in her introduction, these pieces record a kind of Indian urban modernity that encompasses ways of interacting with nature that are now gradually disappearing. It’s too much to hope for a meaningful return to that idyllic world (I certainly wouldn’t be optimistic about it, given my daily encounters with “respected” members of my neighbourhood who seem to view most animals and birds as pests that should be removed from their sight), but a book like this is a reminder of what such a world could look like, and how much we have lost on the road to “development”. It is also a nourishing look – as valuable as a good autobiography – into the mind of an important writer who came to view all life as part of a single shared consciousness.

[My earlier Scroll pieces are here. And a related post: wolves, humans, colony dogs]

August 20, 2021

Helen on the rocks (and other "frozen" women)

[a version of my column for the Sunday Economic Times -- this one about how a gripping Malayalam film subverts the "fridging" theme]

----------------------------------

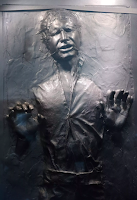

When is a woman in a refrigerator more than just a woman in a refrigerator? The answer can vary with your perspective or interpretation – but the reference, in case you’re wondering, is to a term coined by the comic-book writer Gail Simone. Also known as “fridging”, it describes a certain trope in literature and film: an imperilled, murdered or generally non-functional woman character becomes the pretext for the emotional development (or the plot-furthering emotional devastation) of a man.

In many of these cases, a token effort is made to create empathy for the victim, but she’s basically a cipher for plot purposes, and it’s all about the fellow’s journey. (Comatose or dead women are particularly useful; they can’t even complain that a man is man-spreading his way across the narrative.) Formulaic vigilante-revenge films use this frozen woman, and so do more nuanced stories. A recent example I saw was a scene in season one of The Crown: old Winston Churchill has a personal epiphany – leading to a shift in prime-ministerial policy – during the Great Smog of 1952 as he regards the fate of his secretary Venetia (a character created and killed off specifically for the show).  Venetia’s body is laid out on ice in the morgue in that scene, but fridging doesn’t have to involve an actual fridge or ice slab. Even a film like October, written with sensitivity and attention to detail by a woman (Juhi Chaturvedi), can fit the theme for those who like to use such lenses in their assessments: after all, the story is about a young woman (whom we might initially have expected to be the film’s “heroine”) having a terrible accident within the first 15 minutes, and a young man coming of age and gaining in sensitivity and experience because he feels somehow responsible for her in her vegetative state.

Venetia’s body is laid out on ice in the morgue in that scene, but fridging doesn’t have to involve an actual fridge or ice slab. Even a film like October, written with sensitivity and attention to detail by a woman (Juhi Chaturvedi), can fit the theme for those who like to use such lenses in their assessments: after all, the story is about a young woman (whom we might initially have expected to be the film’s “heroine”) having a terrible accident within the first 15 minutes, and a young man coming of age and gaining in sensitivity and experience because he feels somehow responsible for her in her vegetative state.  Which is to say that one can argue endlessly about what constitutes fridging, whether it fits a particular case, whether it is done well (following a story’s internal logic) or cynically – and whether it should even be required for a victim, woman or man, to have any “agency” in such a narrative, given that this is often not the case in real life. (Or in far-away galaxies: remember Han Solo frozen in carbonite at the end of the second Star Wars film, his mouth open as if someone yelled “Statue!” when he was mid-wisecrack?)

Which is to say that one can argue endlessly about what constitutes fridging, whether it fits a particular case, whether it is done well (following a story’s internal logic) or cynically – and whether it should even be required for a victim, woman or man, to have any “agency” in such a narrative, given that this is often not the case in real life. (Or in far-away galaxies: remember Han Solo frozen in carbonite at the end of the second Star Wars film, his mouth open as if someone yelled “Statue!” when he was mid-wisecrack?)

But one of the sharpest takes on fridging that I have seen is in the 2019 film Helen. This is among many recent Malayalam films that do intriguing things with their narrative arcs: just when you think the film is about to settle into a predictable (if engrossing) story “type”, the screenplay takes an unnerving right turn, a new character or complication is introduced – and somehow, all this is pulled off without altering the film’s basic grounded tone.

These shifts in arc make it hard to discuss such films in spoiler-free terms, but I’ll try. For reasons you’ll understand when you watch Helen, the protagonist (played by the very likable Anna Ben), a Christian with a Muslim boyfriend, ends up as a refrigerated woman around 45 minutes into the story. Alive, more or less functional, but in big trouble. What happens to Helen can be viewed in symbolic terms: thanks to a run-in with police a day earlier when she was with her boyfriend Azhar, she is already in a tight spot, feeling trapped and helpless; her father is giving her the cold shoulder (or putting the freeze on her).  But what happens is also presented in realistic terms, with a plausible build-up – one that involves our familiarity with the nature of Helen’s work, the equations between her colleagues, the workplace routine. The circumstances of her life both facilitate the incident and hinder attempts to rescue her. (A callous policeman goes out of his way to delay the investigation because he disapproves of a young woman associating with a boy from another community and keeping late hours at work.)

But what happens is also presented in realistic terms, with a plausible build-up – one that involves our familiarity with the nature of Helen’s work, the equations between her colleagues, the workplace routine. The circumstances of her life both facilitate the incident and hinder attempts to rescue her. (A callous policeman goes out of his way to delay the investigation because he disapproves of a young woman associating with a boy from another community and keeping late hours at work.)

However, Helen turns out to be the antithesis of the fridged woman as defined by Gail Simone. Though a number of men, including her despairing father and boyfriend, are out looking for her – all primed to become male saviours – she gets the most screen time and her survival is as much a matter of her own resourcefulness, her ability to draw on past experience, to stay in the moment and think things through. And personality: at one point crucial help comes from an anonymous man who remembered her because she was friendly to him.  The result is both a slice-of-life story about regular people and an unusual, nail-biting survival thriller. It’s also a rare example – at a time when too many films wear their social consciousness or political correctness on their sleeve – of a movie that subverts an old motif without coming across as laboured in its progressiveness. It makes one want to tell the more overtly “woke” filmmakers to take a chill-pill, or at least to sit in an icebox for a bit.

The result is both a slice-of-life story about regular people and an unusual, nail-biting survival thriller. It’s also a rare example – at a time when too many films wear their social consciousness or political correctness on their sleeve – of a movie that subverts an old motif without coming across as laboured in its progressiveness. It makes one want to tell the more overtly “woke” filmmakers to take a chill-pill, or at least to sit in an icebox for a bit.

[Last month's Economic Times column -- about Haseen Dillruba -- is here]

August 9, 2021

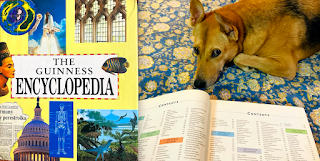

The "30 years ago" series: my Guinness Encyclopaedia

This big fat single-volume encyclopaedia was one of the most exciting things that happened to me in the summer of 1991. If it looks new for a book that has been collecting dust in a corner of my room for decades, here’s one reason: last week, for the first time, I removed the thin plastic jacket that had been wrapped around the book (with scotch-tape!) to prevent it from early wear and tear. (I don’t remember now if this is how the book was delivered to us, or if it’s something my mother did after it arrived – we middle-class soft-socialists routinely did such things to car seats and even sofa covers.) When the cover was off, along with the dirt trapped in it, the encyclopaedia was bright and shiny apart from a rip or a scratch here and there.

This big fat single-volume encyclopaedia was one of the most exciting things that happened to me in the summer of 1991. If it looks new for a book that has been collecting dust in a corner of my room for decades, here’s one reason: last week, for the first time, I removed the thin plastic jacket that had been wrapped around the book (with scotch-tape!) to prevent it from early wear and tear. (I don’t remember now if this is how the book was delivered to us, or if it’s something my mother did after it arrived – we middle-class soft-socialists routinely did such things to car seats and even sofa covers.) When the cover was off, along with the dirt trapped in it, the encyclopaedia was bright and shiny apart from a rip or a scratch here and there.I don’t remember where we first saw an ad for it, but I know it was ordered (by “demand draft”, courtesy a visit to the Malviya Nagar post-office) sometime in early 91, and I had to wait many weeks before it was delivered – on April 30, my diary tells me. Other things I was doing that week included: watching a videocassette of Ajooba for a second time and feeling rueful that the film had been confirmed a “flop” (I wrote about this a few months ago); watching Afsana Pyaar Ka with its lilting “Tip Tip Tip Tip Baarish” song (in later years I keep confusing this film in my head with the Aamir-Madhuri-starrer Deewana Mujhsa Nahin); buying and obsessively listening to the audio-cassettes of soon-to-be-released films like Lekin and Saajan; continuing my discovery of writers like PG Wodehouse and Saki and Somerset Maugham; nurturing my recent interest in serial-killer literature, especially Jack the Ripper (and being very scared by the miniseries starring Michael Caine and the London fog); fretting about class tests and diligently listing the marks of at least 15 of my classmates whenever the results of any test, however minor, came out.

All of that faded into the background for a while when the Guinness Encyclopaedia arrived. I returned one afternoon from school to find it on my bed, and spent most of the rest of that day greedily flipping through it, marveling at the vividness of the photos and illustrations, the quality of the paper, the sheer size and breadth of the thing. (It was unquestionably the most expensive book that had ever been bought for me, priced close to 2000 rupees if I remember right.)

All of that faded into the background for a while when the Guinness Encyclopaedia arrived. I returned one afternoon from school to find it on my bed, and spent most of the rest of that day greedily flipping through it, marveling at the vividness of the photos and illustrations, the quality of the paper, the sheer size and breadth of the thing. (It was unquestionably the most expensive book that had ever been bought for me, priced close to 2000 rupees if I remember right.)“The Guinness Encyclopaedia is a completely new kind of single-volume encyclopaedia,” began the introductory note by the editor, Ian Crofton. While other single-volume encyclopaedias were arranged as A to Z listings, “useful for looking up a quick reference or checking a fact, but unable to present the reader with a complete overview of a subject”, this one was divided into 12 main sections – the physical sciences, animals and plants, history, the visual arts, and so on, with each section then sub-divided into a series of indepth articles on key topics. "It does not just list facts – it explains them, and puts them in context." I remember being very impressed by this claim, and by the large, elegantly laid out Contents page that confirmed it.

Some of the inside pages you see here are among the ones I returned to very often. When I opened the book recently – for the first time in years – the very sight of these pages (just the arrangement of the photos, the familiarity of the captions, a memory of seeing an action image of John Wayne in Stagecoach, long before I had watched the film) was a Proustian trigger. (Inevitably, since my Old Hollywood obsession began in earnest around the same time that the encyclopaedia arrived, I spent a lot of time looking at the film pages – not that there were many of them. A couple of the other, more prosaic-looking encyclopaedias I bought around the same time – the A-to-Z ones, like the Hutchinson Encyclopaedia – served the important function of telling me about the birth dates and years of the film personalities I was interested in.)

Some of the inside pages you see here are among the ones I returned to very often. When I opened the book recently – for the first time in years – the very sight of these pages (just the arrangement of the photos, the familiarity of the captions, a memory of seeing an action image of John Wayne in Stagecoach, long before I had watched the film) was a Proustian trigger. (Inevitably, since my Old Hollywood obsession began in earnest around the same time that the encyclopaedia arrived, I spent a lot of time looking at the film pages – not that there were many of them. A couple of the other, more prosaic-looking encyclopaedias I bought around the same time – the A-to-Z ones, like the Hutchinson Encyclopaedia – served the important function of telling me about the birth dates and years of the film personalities I was interested in.) I don’t think my fascination with the book lasted more than a few months – and I never read a whole section of it from beginning to end (it was more about browsing through it a lot, and revisiting specific pages or sections) – but it had pride of place in the house for the longest time. It had a specific spot on a small table, and was never left lying around like the Wodehouses or Maughams or magazines or Archie comics. While other books could be reached for while lolling on the bed, picking up the Guinness and carrying it to a table to pore over it was a full-blown ritual; the size and weight ensured that. I had no idea back then what a coffee-table book was (and I’m sure we didn’t have any others in the house), but the Encyclopaedia was treated with the same care and respect that a very expensive coffee-table publication would be. I’m not sure it would make any sense to put it on a list of “My Favourite Books”, but it was certainly one of the most special.

I don’t think my fascination with the book lasted more than a few months – and I never read a whole section of it from beginning to end (it was more about browsing through it a lot, and revisiting specific pages or sections) – but it had pride of place in the house for the longest time. It had a specific spot on a small table, and was never left lying around like the Wodehouses or Maughams or magazines or Archie comics. While other books could be reached for while lolling on the bed, picking up the Guinness and carrying it to a table to pore over it was a full-blown ritual; the size and weight ensured that. I had no idea back then what a coffee-table book was (and I’m sure we didn’t have any others in the house), but the Encyclopaedia was treated with the same care and respect that a very expensive coffee-table publication would be. I’m not sure it would make any sense to put it on a list of “My Favourite Books”, but it was certainly one of the most special.

Ten years later, when I left my first job at Encyclopaedia Britannica, a parting gift was the 32-volume set of the EB. Highly valued as that set is (both as a prestige possession and as an oversized memento of my time at Britannica), it was relegated first to a steel cupboard and later to a box-bed, and has stayed out of view for months at a time. But the Guinness Encyclopaedia remained in my room long after I had ceased reading it, usually in plain sight, as one of those things that can help raise a small table to a desired height, or as something to keep my laptop on. (Try doing that with Wikipedia.)

[Earlier 1991 posts: two murders; Ajooba; my movie guide]

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers